Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

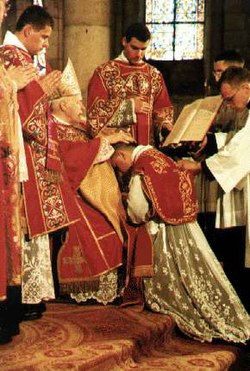

Ordination

View on Wikipedia

Ordination is the process by which individuals are consecrated, that is, set apart and elevated from the laity class to the clergy, who are thus then authorized (usually by the denominational hierarchy composed of other clergy) to perform various religious rites and ceremonies.[1] The process and ceremonies of ordination may vary by religion and denomination. One who is in preparation for, or who is undergoing, the process of ordination is sometimes called an ordinand. The liturgy used at an ordination is commonly found in a book known as an Ordinal which provides the ordo (ritual and rubrics) for celebrations.

Christianity

[edit]Catholic, Orthodox, Lutheran and Anglican churches

[edit]

In Catholicism and Orthodoxy, ordination is one of the seven sacraments, variously called holy orders or cheirotonia ("Laying on of Hands").

Apostolic succession is considered an essential and necessary concept for ordination in the Catholic, Orthodox, High Church Lutheran, Moravian, and Anglican traditions, with the belief that all ordained clergy are ordained by bishops who were ordained by other bishops tracing back to bishops ordained by the Apostles who were ordained by Christ, the great High Priest (Hebrews 7:26, Hebrews 8:2), who conferred his priesthood upon his Apostles (John 20:21–23, Matthew 28:19–20, Mark 16:15–18, and Acts 2:33).[2][3][4]

There are three ordinations in Holy Orders: deacon, presbyter, and bishop. Both bishops and presbyters are priests and have authority to celebrate the Eucharist. In common use, however, the term priest, when unqualified, refers to the order of presbyter, whereas presbyter is mainly used in rites of ordination and other places where a technical and precise term is required.[citation needed]

Ordination of a bishop is performed by several bishops; ordination of a priest or deacon is performed by a single bishop. The ordination of a new bishop is also called a consecration. Many ancient sources specify that at least three bishops are necessary to consecrate another, e.g., the 13th Canon of the Council of Carthage (AD 394) states, "A bishop should not be ordained except by many bishops, but if there should be necessity he may be ordained by three,"[5] and the first of "The Canons of the Holy and Altogether August Apostles" states, "Let a bishop be ordained by two or three bishops," while the second canon thereof states, "Let a presbyter, deacon, and the rest of the clergy, be ordained by one bishop";[6] the latter canons, whatever their origin, were imposed on the universal church by the Seventh Ecumenical Council, the Second Council of Nicaea, in its first canon.[7]

Details peculiar to the various denominations

[edit]The Catholic Church teaches that one bishop is sufficient to consecrate a new bishop validly (that is, for an episcopal ordination actually to take place). In most Christian denominations that retain the practice of ordination, only an already ordained (consecrated) bishop or the equivalent may ordain bishops, priests, and deacons.[8] However, Canon Law requires that bishops always be consecrated with the mandate (approval) of the Pope, as the guarantor of the Church's unity.[9] Moreover, at least three bishops are to perform the consecration, although the Apostolic See may dispense from this requirement in extraordinary circumstances (for example, in missionary settings or times of persecution).[10]

In the Catholic Church, those deacons destined to be ordained priests are often termed transitional deacons; those deacons who are married before being ordained, as well as any unmarried deacons who chose not to be ordained priests, are called permanent deacons. Those married deacons who become widowers have the possibility of seeking ordination to the priesthood in exceptional cases.[11]

While some Eastern churches have in the past recognized Anglican ordinations as valid,[12] the current Anglican practice, in many provinces, of ordaining women to the priesthood—and, in some cases, to the episcopate—has caused the Orthodox generally to question earlier declarations of validity and hopes for union.[13] Anglicanism recognizes Catholic and Orthodox ordinations; hence, clergy converting to Anglicanism are not "re-ordained". In 1896, Pope Leo XIII issued the papal bull Apostolicae Curae, which declared Anglican orders "absolutely null and utterly void."[14] While the Vatican has not officially retracted the statement, Roman Catholic actions after the issuance of the bull imply varying positions on the matter. In modern times, the Pope has on several occasions gifted to the Archbishop of Canterbury signs of ecclesiastical office, including a crozier,[15] an episcopal ring,[16] and a Eucharistic chalice,[17] signaling a softening on the Roman view of Anglican orders. In addition, under Pope Francis' tenure, an Anglican bishop was allowed to celebrate mass on the altar of the Archbasilica of Saint John Lateran,[18] the seat of the Pope's own bishopric.

With respect to Lutheranism, "the Catholic Church has never officially expressed its judgement on the validity of orders as they have been handed down by episcopal succession in these two national Lutheran churches" (the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Sweden and the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland) though it does "question how the ecclesiastical break in the 16th century has affected the apostolicity of the churches of the Reformation and thus the apostolicity of their ministry".[19][20]

Some Eastern Orthodox churches recognize Catholic ordinations while others "re-ordain" Catholic clergy (as well as Anglicans) who convert. However, both the Catholic and Anglican churches recognize Orthodox ordinations.

In the Catholic and Anglican churches, ordinations have traditionally been held on Ember Days, though there is no limit to the number of clergy who may be ordained at the same service. In the Eastern Orthodox Church, ordinations may be performed any day of the year on which the Divine Liturgy may be celebrated (and deacons may also be ordained at the Presanctified Liturgy), but only one person may be ordained to each order at any given service, that is, at most one bishop, one presbyter, and one deacon may be ordained at the same liturgy.[21]

Notes

[edit]

- There have long existed orders of clergy below that of deacon. In the Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox churches (and, until 1970, in the Catholic Church), a person has to be tonsured a cleric and be ordained to sundry minor orders prior to being ordained a deacon. Although a person may be said to be ordained to these orders, such ordinations are not reckoned as part of the sacrament of Holy Orders; in the Eastern Orthodox, the term Cheirothesia ("imposition of hands")[21] is used for such ordinations in contrast to Cheirotonia ("laying on of hands") for ordinations of deacons, presbyters, and bishops.

- The following are positions that are not acquired by ordination:

- Becoming a monk or nun or, generally, a member of a religious order, which is open to men and women; men in religious orders may or may not be ordained. Anglican nuns may, like their male counterparts, be ordained as well.

- Offices and titles such as pope, patriarch, archbishop, archpriest, archimandrite, archdeacon, etc., which are given to ordained persons for sundry reasons, e.g., to rank them or honor them.

- Cardinals are simply a large collegiate body who are electors of and the senior-most counselors to the Pope, and are not a fourth order beyond bishop. At presently nearly all cardinals are bishops, although several are priests, having been granted a dispensation from being ordained a bishop by the Pope (most of these were elevated by the Pope for services to the Church, and are over 80, thus not having the right to elect a pope or have active voting memberships in Vatican departments). As recently as 1899 there was a cardinal who was a deacon when he died, having been a cardinal for 41 years (Teodolfo Mertel). There have even been noble lay men, or men who only possessed minor orders (now called ministries, and carried out by seminarians and laypeople) who at one time were made cardinals. Cardinals are considered princes in diplomatic protocol and by the Church, and even if they are not ordained bishops and cannot perform episcopal functions such as ordination, they have both real and ceremonial precedence over all non-cardinal patriarchs, archbishops, and bishops. Some have discussed the possibility in Catholicism of having women serve as cardinals or, more realistically in the short-term, as sub-deacons, since they cannot be ordained[citation needed].

- In the Church of England, the priest of the diocese who oversees the process of discernment, selection and training of ordinands is usually called the "Diocesan Director of Ordinands", commonly shortened to "DDO". He or she may have a team of assistants, who may be called Assistant DDOs or Vocations Advisers.

Reformed, Methodist and Pentecostal churches

[edit]

In most Protestant churches, ordination is the rite by which their various churches:

- recognize and confirm that an individual has been called by God to ministry,

- acknowledge that the individual has gone through a period of discernment and training related to this call (e.g. having graduated from a seminary), and

- authorize that individual to take on the office of ministry.

For the sake of authorization and church order, and not for reason of 'powers' or 'ability', individuals in most mainline Protestant churches must be ordained in order to preside at the sacraments (Baptism and Holy Communion), and to be installed as a called pastor of a congregation or parish.

Some Protestant traditions have additional offices of ministry to which persons can be ordained. For instance:

- most Presbyterian and Reformed churches maintain a threefold order of ministry of pastor, elder, and deacon. The order of Pastor, the only one of the three orders considered "clergy", is comparable to most other denominations' pastoral office or ordained ministry. The order of elder comprises lay persons ordained to the ministries of church order and spiritual care (for example, elders form the governing bodies of congregations and are responsible for a congregation's worship life). In many Presbyterian churches, the pastor or minister is seen as a "teaching elder" and is equal to the other elders in the session. The order of deacon comprises lay persons ordained to ministries of service and pastoral care. Those who fill this position may be known as "ruling elders".

- Deacons are also ordained in the Lutheran,[22] Methodist[23] and in most of the Baptist traditions.[24]

For most Protestant denominations that have an office of bishop, including certain Lutheran and many Methodist churches, this is not viewed as a separate ordination or order of ministry. Rather, bishops are ordained ministers of the same order as other pastors, simply having been "consecrated" or installed into the "office" (that is, the role) of bishop. However, some Lutheran churches also claim valid apostolic succession.[25]

Some Protestant churches – especially Pentecostal ones – have an informal tier of ministers. Those who graduate from a bible college or take a year of prescribed courses are licensed ministers. Licensed ministers are addressed as "Minister" and ordained ministers as "Reverend." They, and also Evangelical pastors, are generally ordained at a ceremony called "pastoral consecration".[26][27][28]

Jehovah's Witnesses

[edit]Jehovah's Witnesses consider an adherent's baptism to constitute ordination as a minister.[29] Governments have generally recognized that Jehovah's Witnesses' full-time appointees (such as their "regular pioneers") qualify as ministers[30] regardless of sex or appointment as an elder or deacon ("ministerial servant"). The religion asserts ecclesiastical privilege only for its appointed elders,[31][32] but the religion permits any baptized adult male in good standing to officiate at a baptism, wedding, or funeral.[33]

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

[edit]In the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, a rite of ordination is performed to bestow either the Aaronic or Melchizedek priesthood (Hebrews 5:4–6) upon a worthy male member. As in the Anglican, Catholic and Orthodox traditions, great care is taken to assure that the candidate for priesthood is ordained by those with proper authority and ordained properly and validly; thorough records of priesthood ordination are kept by the church. Ordination is performed by the laying on of hands. Ordination to the office of priest in the Aaronic priesthood gives the ordained person the authority to:

- baptize converts and children over the age of 8 into the church

- bless and administer the sacrament (the Lord's Supper)

- participate in, or perform, ordinations of others to the Aaronic Priesthood or its offices

- collect fast offerings for the Bishop (usually ordained Deacons and Teachers perform this)

Ordination to the Melchizedek priesthood includes the authority to perform all the duties of the Aaronic priesthood, as well as ordain others to the Melchizedek or Aaronic priesthood, perform confirmations, bless and anoint the sick with oil, bless and dedicate graves, and other such rites. There are five offices within the Melchizedek Priesthood to which one could potentially be ordained:

"Ordination to an office in the Aaronic Priesthood is done by or under the direction of the bishop or branch president. Ordination to an office in the Melchizedek Priesthood is done by or under the direction of the stake or mission president. To perform a priesthood ordination, one or more authorized priesthood holders place their hands lightly on the person's head."[34]

Latter-day Saints believe in a line of priesthood authority that traces back to Jesus Christ and his apostles. LDS adherents believe the church's founder, Joseph Smith, was ordained under the hands of apostles Peter, James, and John, who appeared to Smith as angelic messengers in 1829.[35]

Islam

[edit]Islam has no formal clergy or ordained religious leaders. Ordination is viewed as a distinct aspect of other religions and is rejected.[citation needed]

Instead, the faith’s religious leaders are usually called imams, sheikhs, or mawlānā—none of which imply ordination. The title imam (when not referring to the Shi'a doctrine of the Imamate) is given to an individual who leads Muslims in salah; the term can also be used in a linguistic sense for anyone who leads other Muslims in congregational prayers. Sheikh (Arabic: شَيْخ, 'elder' or 'noble') is an Arabic honorific title for a male Islamic scholar or tribal chieftain; shaikhah (شيخة) refers to a female learned in Islamic issues. The title is usually more prevalent in Arabic countries. The word mawlana is a title bestowed upon students who have graduated from a madrasa (Islamic theological academy) throughout the Indian subcontinent. Although Muslim schools, universities, and madrasas might follow different graduation ceremonies upon a student's completion of a 4-year undergraduate program in Islamic studies or a 7–8-year 'alim course, their respective ceremonies neither symbolize nor confer ordination.

Judaism

[edit]The ordination of a rabbi within Judaism is referred to as semikhah (Hebrew: סמיכה, 'leaning' or 'laying [of the hands]'; or semicha lerabanim סמיכה לרבנות, 'rabbinical ordination'). The term is derived from the Hebrew verb for "to lean [up]on" (לִסְמוֹך, lismôq) in the sense that prospective rabbis are "to be authorized" as Jewish religious leaders.

While the Hebrew word semikhah is rendered as "ordination" in English, a rabbi is not a priest per se. Rather, ordained rabbis, at least until the 20th century (when the role of rabbis expanded to included pastoral duties) primarily function as Jewish communities' decisors of Halakha (Jewish law) and Torah teachers and scholars.[36] For many Jewish religious purposes, a rabbi's presence is unnecessary. For example, at prayer, a minyan (quorum) of ten laypeople is both necessary and sufficient for the recital of Kaddish—thus the saying "nine rabbis do not constitute a minyan, but ten cobblers can".[37]

Recently, in some Jewish religious movements, semikhah or semicha lehazzanut may refer to the ordination of a hazzan (cantor); some use the term "investiture" to describe the conferral of cantorial authority rather than ordination.

Buddhism

[edit]

The tradition of the ordained monastic community (sangha) began with the Buddha, who established orders of monks and later of nuns. The procedure of ordination in Buddhism is laid down in the Vinaya and Patimokkha or Pratimoksha scriptures. There exist three intact ordination lineages nowadays in which one can receive an ordination according to the Buddha's teachings:[citation needed]

- Dharmaguptaka Lineage

- Mulasarvastivadin Lineage

- Theravada Lineage

Mahayana

[edit]Saicho repeatedly requested that the Japanese government allow the construction of a Mahayana ordination platform. Permission was granted in 822 CE, seven days after Saicho died. The platform was finished in 827 CE at Enryaku-ji on Mount Hiei, and was the first in Japan. Prior to this, those wishing to become monks/nuns were ordained using the Hinayana precepts, whereas after the Mahayana ordination platform, people were ordained with the Bodhisattva precepts as listed in the Brahma Net Sutra.[38]

Theravada

[edit]Pabbajjā is an ordination procedure for samaneras, novice monks in the Theravada tradition.

Fully ordained nuns

[edit]The legitimacy of fully ordained nuns (bhikkhuni/bhiksuni) has become a significant topic of discussion in recent years. Texts passed down in every Buddhist tradition record that Gautama Buddha created an order of fully ordained nuns, but the tradition has died out in some Buddhist traditions such as Theravada Buddhism, while remaining strong in others such as Chinese Buddhism (Dharmaguptaka lineage). In the Tibetan lineage, which follows the Mulasarvastivadin lineage, the lineage of fully ordained nuns was not brought to Tibet by the Indian Vinaya masters, hence there is no rite for the ordination of full nuns. However the 14th Dalai Lama has endeavored for many years to improve this situation.[39] In 2005, he asked fully ordained nuns in the Dharmaguptaka lineage, especially Jampa Tsedroen, to form a committee to work for the acceptance of the bhiksuni lineage within the Tibetan tradition,[39] and donated €50,000 for further research. The "1st International Congress on Buddhist Women's Role in the Sangha: Bhikshuni Vinaya and Ordination Lineages" was held at the University of Hamburg from 18 to 20 July 2007, in cooperation with the university's Asia-Africa Institute. Although the general tenor was that full ordination was overdue, the Dalai Lama presented a pre-drafted statement[40] saying that more time was required to reach a decision, thus nullifying the intentions of the congress.

Posthumous ordination

[edit]In Medieval Sōtō Zen, a tradition of posthumous ordination was developed to give the laity access to Zen funeral rites. Chinese Ch’an monastic codes, from which Japanese Sōtō practices were derived, contain only monastic funeral rites; there were no provisions made for funerals for lay believers. To solve this problem, the Sōtō school developed the practice of ordaining laypeople after death, thus allowing monastic funeral rites to be used for them as well.[41]

New Kadampa Tradition

[edit]The Buddhist ordination tradition of the New Kadampa Tradition-International Kadampa Buddhist Union (NKT-IKBU) is not the traditional Buddhist ordination, but rather one newly created by Kelsang Gyatso. Although those ordained within this organisation are called 'monks' and 'nuns' within the organisation, and wear the robes of traditional Tibetan monks and nuns, in terms of traditional Buddhism they are neither fully ordained monks and nuns (Skt.: bhikshu, bhikshuni; Tib.: gelong, gelongma) nor are they novice monks and nuns (Skt.: sramanera, srameneri; Tib.: gestul, getsulma).[42][43][44]

Unlike most other Buddhist traditions, including all Tibetan Buddhist schools, which follow the Vinaya, the NKT-IKBU ordination consists of the Five Precepts of a lay person, plus five more precepts created by Kelsang Gyatso. He is said to view them as a "practical condensation" of the 253 Vinaya vows of fully ordained monks.[42]

There are also no formal instructions and guidelines for the behaviour of monks and nuns within the NKT. Because the behaviour of monks and nuns is not clearly defined "each Resident Teacher developed his or her own way of 'disciplining' monks and nuns at their centres ...".[45]

Kelsang Gyatso's ordination has been publicly criticised by Geshe Tashi Tsering as going against the core teachings of Buddhism and against the teachings of Tsongkhapa, the founder of the Gelugpa school from which Kelsang Gyatso was expelled[46][47][48]

Unitarian Universalism

[edit]As Unitarian Universalism features very few doctrinal thresholds for prospective congregation members, ordinations of UU ministers are considerably less focused upon doctrinal adherence than upon factors such as possessing a Masters of Divinity degree from an accredited higher institution of education and an ability to articulate an understanding of ethics, spirituality and humanity.

In the Unitarian Universalist Association, candidates for "ministerial fellowship" with the denomination (usually third-year divinity school students) are reviewed, interviewed, and approved (or rejected) by the UUA Ministerial Fellowship Committee (MFC). However, given the fundamental principle of congregational polity, individual UU congregations make their own determination on ordination of ministers, and congregations may sometimes even hire or ordain persons who have not received UUA ministerial fellowship, and may or may not serve the congregation as its principal minister/pastor.

Ordination of women

[edit]The ordination of women is often a controversial issue in religions where either the office of ordination, or the role that an ordained person fulfills, is traditionally restricted to men, for various theological reasons.

In Christianity

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2020) |

The Christian priesthood has traditionally been reserved to men. Some historians, such as Peter Brown and Gary Macy, mention that women were ordained deacons in the first millennium of Christianity. After the Protestant Reformation and the loosening of authority structures within many denominations, most Protestant groups re-envisioned the role of the ordained priesthood. Many did away with it altogether. Others altered it in fundamental ways, often favoring a rabbinical-type married minister of teaching (word) and discarding any notion of a sacrificial priesthood. A common epithet used by Protestants (especially Anglicans) against Catholics was that Catholics were a 'priest-ridden' people. Hatred for priests was a common element of anti-Catholicism and pogroms against Catholics focused on expelling, killing, or forcefully 'laicizing' priests.[citation needed]

Beginning in the twentieth century, many Protestant denominations began re-evaluating the roles of women in their churches. Many now ordain women.[citation needed] According to the biblical book of Judges, a wise and brave woman named Deborah was the fourth judge of the ancient Israelites. She was instrumental in implementing a strategic military strategy that delivered the Israelites from the oppressive Canaanite king Jabin. Likewise, Jael was courageous and primary in the Israelite victory. Her prudent actions killed the commander Sisera after he fled on foot following the battle. Within the Book of Judges, there is a repetitive cycle of sin and deliverance. There is also a proposition regarding the cyclical offenses: "In those days Israel had no king; all the people did whatever seemed right in their own eyes" (Jdg. 21:25). Based partially upon the leadership of the prophetess, Deborah, some Protestant and non-denominational organizations grant ordination to women. Other denominations refute the claim of a precedent based on Deborah's example because she is not specifically described as ruling over Israel, rather giving judgments on contentious issues in private, not teaching publicly,[49] neither did she lead the military.[49][50] Her message to her fellow judge Barak in fact affirmed the male leadership of Israel.[49][50] The United Church of Canada has ordained women since 1932. The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America ordains women as pastors, and women are eligible for election as bishops. The Episcopal Church in the United States of America ordains women as deacons, priests and bishops. The Lutheran Evangelical Protestant Church ordains women at all levels including deacon, priest and bishop. Other denominations leave the decision to ordain women to the regional governing body, or even to the congregation itself; these include the Christian Reformed Church in North America and the Evangelical Presbyterian Church. The ordination of women in the latter half of the 20th century was an important issue between Anglicans and Catholics since the Catholic Church viewed the ordination of women as a huge obstacle to possible rapprochement between the two churches.[citation needed]

The Catholic Church has not changed its view or practice on the ordination or women, and neither have any of the Orthodox churches; these churches represent approximately 65% of all Christians worldwide. In response to the growing call for the ordination of women, Pope John Paul II issued the statement Ordinatio sacerdotalis in 1995. In it, he gave reasons why women cannot be ordained, and defined that the Holy Spirit had not conferred the power to ordain women upon the Church. In the wake of this definitive statement, many theologians considered the issue settled, but many continue to push for the ordination of women in the Catholic Church. Some have even begun protest churches.[citation needed]

In Judaism

[edit]Policy regarding the ordination of women differs among the different denominations of Judaism. Most Orthodox congregations do not allow female rabbis, while more liberal congregations began allowing female rabbis by the middle of the twentieth century.

Ordination of LGBT persons

[edit]Most Abrahamic religions condemn the practice of homosexuality and the Bible has been interpreted that in Romans 1 that homosexuals are "worthy of death". Interpretation of this passage, as with others potentially condemning homosexuality varies greatly between and within different denominations. Beginning in the late 20th century, and more so in the early 21st century, several mainline denominational sects of Christianity and Judaism in the US and Europe endorsed the ordination of openly LGBT persons. See LGBT clergy in Christianity.

The United Church of Christ ordained openly gay Bill Johnson in 1972, and lesbian Anne Holmes in 1977.[51]

While Buddhist ordinations of openly LGBT monks have occurred, more notable ordinations of openly LGBT novitiates have taken place in Western Buddhism.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ From a sociological perspective, ordination legitimates the ordinand's role as clergy and performance of rituals. Pogorelc, Anthony J. (21 April 2021). "Social Construction of the Sacrament of Orders". Religions. 12 (5): 290. doi:10.3390/rel12050290. ISSN 2077-1444.

- ^ "Sacrament of the Holy Priesthood". Archived from the original on 17 December 2005. Retrieved 3 August 2011. "The Orthodox Faith — The Sacrament of the Holy Priesthood", Retrieved 3 August 2011

- ^ König, Andrea (2010). Mission, Dialog und friedliche Koexistenz: Zusammenleben in einer multireligiösen und säkularen Gesellschaft: Situation, Initiativen und Perspektiven für die Zukunft. Peter Lang. p. 205. ISBN 9783631609453.

Having said that, Lutheran bishops in Sweden or Finland, which retained apostolic succession, or other parts of the world, such as Africa or Asia, which gained it from Scandinavia, could easily be engaged to do something similar in Australia, as has been done in the United States, without reliance on Anglicans.

- ^ Guidry, Christopher R.; Crossing, Peter F. (1 January 2001). World Christian Trends, AD 30 – AD 2200: Interpreting the Annual Christian Megacensus. William Carey Library. p. 307. ISBN 9780878086085.

A number of large episcopal churches (e.g. United Methodist Church, USA) have maintained a succession over 200 years but are not concerned to claim that the succession goes back in unbroken line to the time of the first Apostles. Very many other major episcopal churches, such as the Catholic, Orthodox, Old Catholic, Anglican, and Scandinavian Lutheran, make this claim and contend that a bishop cannot have regular or valid orders unless he has been consecrated in this apostolic succession.

- ^ [1] Archived 14 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, "Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers — The Seven Ecumenical Councils, p641", Retrieved 3 August 2011

- ^ [2] Archived 14 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, "Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers — The Seven Ecumenical Councils, p839", Retrieved 3 August 2011

- ^ [3] Archived 5 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine, "Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers — The Seven Ecumenical Councils, P790", Retrieved 3 August 2011

- ^ Pius XII. "Episcopali consecrationis". Archived from the original on 2 March 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

Episcopalis Consecrationis Ministrum esse Episcopum et ad huius Consecrationis validitatem unum solum sufficere Episcopum, qui cum debita mentis intentione essentiales ritus perficiat, extra omne dubium est diuturnaque praxi comprobatum. [That the minister of episcopal consecration is a bishop, and that only one bishop–who performs the act with the necessary intention of the mind performs the essential rites—is necessary for the validity of that consecration, is proved beyond all doubt and by long practice.]

- ^ "Code of Canon Law – IntraText". Code of Canon Law. Canon 1014. Archived from the original on 2 April 2007.

No bishop is permitted to consecrate anyone a bishop unless it is first evident that there is a pontifical mandate.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ "Code of Canon Law – IntraText". Code of Canon Law. Canon 1014. Archived from the original on 2 April 2007.

Unless the Apostolic See has granted a dispensation, the principal bishop consecrator in an episcopal consecration is to be joined by at least two consecrating bishops; it is especially appropriate, however, that all the bishops present consecrate the elect together with the bishops mentioned.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ National Directory for the Formation, Ministry, and Life of Permanent Deacons in the United States (PDF). Chapter 2, No. 77: United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. p. 37. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 July 2012.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ ""Orthodox Statements on Anglican Orders"" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2011.

- ^ [4] Archived 31 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine"Unity Faith and Order – Dialogues – Anglican Orthodox," Introduction, par. 2 ("From Moscow to Lambeth (1976–8)

- ^ "CATHOLIC LIBRARY: Apostolicae Curae (1896)". www.newadvent.org. Retrieved 23 April 2025.

- ^ "Pope Francis gave Archbishop Justin Welby a replica of the Crozier of St. Gregory the Great ~ IARCCUM.org". iarccum.org. Retrieved 23 April 2025.

- ^ "World: Pope Paul's gift marked moving moment of ecumenical drama". www.natcath.org. Retrieved 23 April 2025.

- ^ Murray, Fr Gerald E. (18 May 2017). "The Truth Is Real, Not Rigid". The Catholic Thing. Retrieved 23 April 2025.

- ^ "Over 50 Anglicans celebrate liturgy at Pope Francis' cathedral after "breakdown in communication"". America Magazine. 20 April 2023. Retrieved 23 April 2025.

- ^ Sullivan, Francis Aloysius (2001). From Apostles to Bishops: The Development of the Episcopacy in the Early Church. Paulist Press. p. 4. ISBN 0809105349.

To my knowledge, the Catholic Church has never officially expressed its judgement on the validity of orders as they have been handed down by episcopal succession in these two national Lutheran churches.

- ^ "Roman Catholic – Lutheran Dialogue Group for Sweden and Finland, Justification in the Life of the Church, section 297, page 101" (PDF).[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Sokolof, Archpriest Dimitrii (1899), Manual of the Orthodox Church's Divine Services, Jordanville, New York: Holy Trinity Monastery (published 2001), pp. 132–136, ISBN 0-88465-067-7, archived from the original on 2 July 2017

{{citation}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ "Assembly recap: A new entrance rite for deacons". 3 October 2019.

- ^ Order of Service: Ordination of a Deacon and Ordination of a Minister of the Word Archived 26 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Uniting Church in Australia,

- ^ "Deacon ordination" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 April 2015.

- ^ Tjørhom, Ola. "The Church and its Apostolicity: The Porvoo Common Statement as a Challenge to Lutheran Ecclesiology and the Nordic Lutheran Churches." The Ecumenical Review 52.2 (2000): 195–203.

- ^ Sébastien Fath, Une autre manière d'être chrétien en France: socio-histoire de l'implantation baptiste, 1810–1950, Editions Labor et Fides, Genève, 2001, p. 578

- ^ William H. Brackney, Historical Dictionary of the Baptists, Scarecrow Press, USA, 2009, p. 431

- ^ Shane Clifton, Pentecostal Churches in Transition: Analysing the Developing Ecclesiology of the Assemblies of God in Australia, BRILL, Netherlands, 2009, p. 134

- ^ "Beliefs—Membership and Organization", Authorized Site of the Office of Public Information of Jehovah's Witnesses, As Retrieved 2009-09-01 Archived 26 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine, "Jehovah's Witnesses have no clergy-laity division. All baptized members are ordained ministers"

- ^ For example, the U.S. Supreme Court case Dickinson v. United States found that Dickinson should have been considered a minister by his draft board because of his ordination by baptism as a Jehovah's Witness and his continued service as a Jehovah's Witness "pioneer". Online Archived 28 May 2001 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Russian Federation Federal Law", Chapter 1, Article 3, Paragraph 7, as cited by Authorized Site of the Office of Public Information of Jehovah's Witnesses, As Retrieved 2009-09-01 Archived 7 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine, "Ecclesiastical privilege is protected by the law. A clergyman may not be prosecuted for refusal to testify on circumstances that became known to him during confession."

- ^ "Who Are Jehovah's Witnesses?", Authorized Site of the Office of Public Information of Jehovah's Witnesses, As Retrieved 2009-09-01 Archived 28 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine, "Who Are Jehovah's Witnesses?...The worldwide organization is directed by an unpaid, ecclesiastical governing body serving at the international offices in Brooklyn, New York."

- ^ "Question Box", Our Kingdom Ministry, November 1973, page 8, "Weddings and funerals may be conducted by any dedicated, baptized brother as permitted by law."

- ^ Duties and Blessings of the Priesthood Part B Lesson 5>

- ^ "Melchizedek Priesthood", Bible Dictionary, KJV (LDS), LDS Church, 1979

- ^ Ostroff, David (4 April 2024). "Rabbi". sources. Retrieved 2 February 2025.

- ^ "Temple Israel Chronicle, January 2009, p3" (PDF). templewb.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ Mahayana Ordination Platform "Soka Gakkai Dictionary of Buddhism."

- ^ a b "Press". www.congress-on-buddhist-women.org. Archived from the original on 15 November 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ "Statement of H.H.-the Dalai Lama". www.congress-on-buddhist-women.org. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ William M. Bodiford, Soto Zen in Medieval Japan (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1993), 195–96.

- ^ a b "New Kadampa Tradition – Kadampa Buddhism (NKT-IKBU) – Kadampa Meditation Center". info-buddhism.com. Archived from the original on 5 July 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ "Vinaya Pitaka: The Basket of the Discipline". www.accesstoinsight.org. Archived from the original on 9 May 2018. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ BuddhaSasana. "What Buddhists Believe – What is Vinaya?". www.budsas.org. Archived from the original on 27 August 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ Realising the Guru's Intention: Hungry Humans and Awkward Animals in a New Kadampa Tradition community by Carol McQuire, in Spiritual and Visionary Communities – Out to Save the World, Ashgate Publishing, 2013, pp. 72–73

- ^ Expulsion letter: "To the Tibetan Buddhists around the world and fellow Tibetan compatriots within and outside Tibet" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ Londonnay ལོན་ཏོན་ནས། (29 October 2015). "(part 1) Geshe Tashi explains Buddhist ordination rite". Archived from the original on 22 September 2016. Retrieved 9 May 2018 – via YouTube.

- ^ Londonnay ལོན་ཏོན་ནས། (2 November 2015). "(part 2) Geshe Tashi challenges NKT Buddhist ordination rite". Archived from the original on 9 May 2018. Retrieved 9 May 2018 – via YouTube.

- ^ a b c "Bible Gateway passage: Judges 4 – English Standard Version". Bible Gateway. Archived from the original on 21 May 2016. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ a b Grudem, Wayne (2004). Evangelical Feminism and Biblical Truth: An Analysis of more than 100 Disputed Questions. Sisters, Oregon: Multnomah Publishers, Inc. p. 864. ISBN 1-57673-840-X. Archived from the original on 3 July 2007.

- ^ "UCC 'Firsts'". www.ucc.org. Archived from the original on 15 November 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

External links

[edit]Ordination

View on GrokipediaOrdination is the formal religious rite by which individuals are consecrated and set apart from the laity to assume roles within the clergy, granting them authority to perform specific ministerial or sacerdotal functions such as preaching, administering sacraments, or rendering religious judgments.[1][2] In Christianity, it typically involves the laying on of hands by existing clergy, a practice rooted in New Testament examples where apostles and elders commissioned deacons and overseers, signifying the transmission of spiritual authority and responsibility for church leadership.[1][3] This rite is considered essential in traditions like Roman Catholicism, where it imparts an indelible sacramental character, distinguishing it from mere recognition of gifts in many Protestant denominations.[3] Analogous ceremonies exist in Judaism as semikhah, which certifies rabbinic expertise in halakhah and authorizes legal decision-making and communal leadership, historically involving physical imposition of hands but now primarily a diploma of proficiency.[4][5] In Buddhism, ordination, known as upasampadā, initiates novices into the monastic sangha as fully ordained monks (bhikkhus) or nuns (bhikkhunis) through ritual recitation of precepts under senior monastics, emphasizing ethical commitment over hierarchical power.[6] Defining characteristics include rigorous preparation, communal affirmation, and ritual elements symbolizing divine commissioning, though debates persist over prerequisites like gender eligibility and the necessity of unbroken lineages, as seen in Catholic assertions of apostolic succession versus broader ecclesiastical validations.[3]