Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

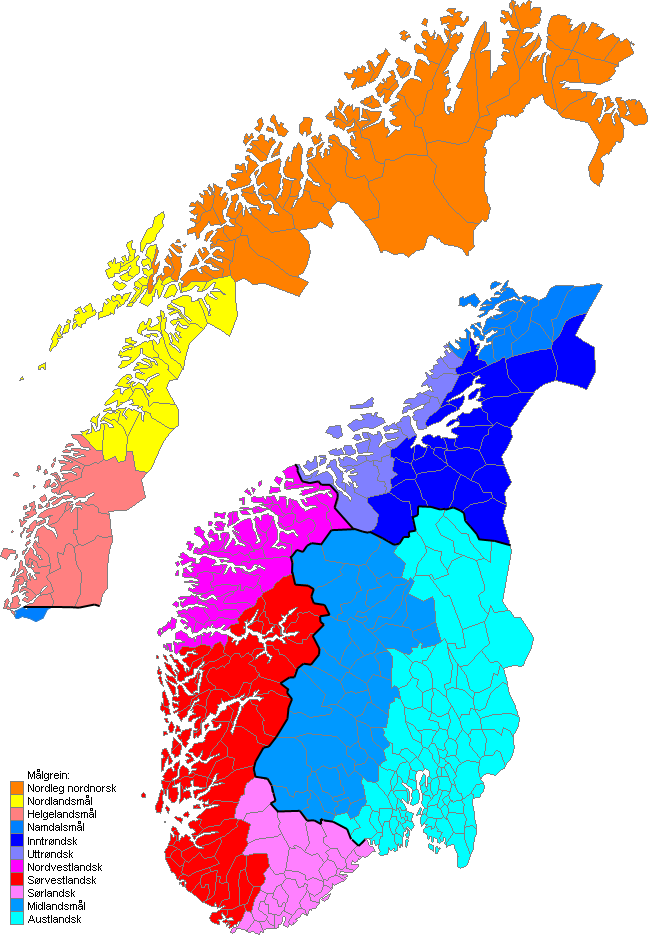

Norwegian dialects

View on Wikipedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2015) |

Norwegian dialects (dialekter/ar) are commonly divided into four main groups, 'Northern Norwegian' (nordnorsk), 'Central Norwegian' (trøndersk), 'Western Norwegian' (vestlandsk), and 'Eastern Norwegian' (østnorsk). Sometimes 'Midland Norwegian' (midlandsmål) and/or 'South Norwegian' (sørlandsk) are considered fifth or sixth groups.[1]

The dialects are generally mutually intelligible, but differ significantly with regard to accent, grammar, syntax, and vocabulary. If not accustomed to a particular dialect, even a native Norwegian speaker may have difficulty understanding it. Dialects can be as local as farm clusters, but many linguists note an ongoing regionalization, diminishing, or even elimination of local variations.[1]

Spoken Norwegian typically does not exactly follow the written languages Bokmål and Nynorsk or the more conservative Riksmål and Høgnorsk, except in parts of Finnmark (where the original Sami population learned Norwegian as a second language). Rather, most people speak in their own local dialect. There is no "standard" spoken Norwegian.

Dialect groups

[edit]- West and South Norwegian

- South Norwegian (most of Agder county plus Fyresdal, Nissedal, Drangedal, and Kragerø in Telemark county)

- South-West Norwegian (the inland parts of Sogn, most of Hordaland (except the city of Bergen), Rogaland county, and western parts of Agder county)

- Bergen Norwegian or Bergensk (the city of Bergen and immediate surroundings)

- North-West Norwegian (the districts of Romsdal, Sunnmøre, Nordfjord, Sunnfjord and outer parts of Sogn)

- North Norwegian

- Helgeland Norwegian (Nordland county south of Saltfjellet, except for Bindal Municipality)

- Nordland Norwegian (Nordland county north of Saltfjellet)

- Troms Norwegian (Troms county, except for Bardu Municipality and Målselv Municipality)

- Finnmark Norwegian Finnmark county, except for northern Kautokeino, northern Karasjok, Tana and Nesseby.

- East Norwegian

- Vikvær Norwegian (Vestfold county, Østfold county, Bohuslän in Sweden, adjacent lowland parts of Telemark county, Buskerud county, and Akershus county)

- Middle East Norwegian (Ringerike, Modum, Oslo and Romerike)

- Oppland Norwegian (southern Hedmark and south-eastern Oppland)

- Østerdal Norwegian (northern Hedmark and Bardu Municipality in northern Norway)

- Midland Norwegian

- Gudbrandsdal Norwegian (northern Oppland)

- Valdres and Hallingdal Norwegian (south-west Oppland and western Buskerud)

- Western Telemark Norwegian (Vinje Municipality, Tokke Municipality and Kviteseid Municipality)

- Eastern Telemark Norwegian (Tinn Municipality, Hjartdal Municipality, Midt-Telemark Municipality, Notodden Municipality and upper Numedal)

- Trøndelag Norwegian

- Outer Trøndelag Norwegian (Nordmøre, outer Sør-Trøndelag, and Fosen)

- Inner Trøndelag Norwegian (inner Sør-Trøndelag, Innherad, Lierne Municipality, and Snåsa Municipality)

- Trondheim Norwegian (Trondheim Municipality)

- Namdal Norwegian (Namdalen and surrounding coastal areas)

- South-eastern Trøndersk (Røros Municipality, Selbu Municipality, Tydal Municipality, Holtålen Municipality, Oppdal Municipality)

- Jämtlandic (Jämtland in Sweden)

- American Norwegian

Dialect branches

[edit]- National Norwegian

- Nordnorsk (Northern Norway)

- Bodø dialect (Bodø)

- Brønnøy dialect (Brønnøy)

- Helgeland dialect (Helgeland)

- other dialects

- Trøndersk (Trøndelag)

- Trondheim dialect (Trondheim)

- Fosen dialect (Fosen)

- Härjedal dialect (Härjedalen)

- Jämtland dialects (Jämtland province)

- Meldal dialect (Meldal)

- Tydal dialect (Tydal)

- other dialects

- Vestlandsk (Western and Southern Norway)

- West (Vestlandet)

- Bergen dialect (Bergen)

- Haugesund dialect (Haugesund)

- Jærsk dialect (Jæren district)

- Karmøy dialect (Karmøy)

- Nordmøre dialects (Nordmøre)

- Romsdal dialect (Romsdal)

- Sandnes dialect (Sandnes)

- Sogn dialect (Sogn district)

- Sunnmøre dialect (Sunnmøre)

- Stavanger dialect (Stavanger)

- Strilar dialect (Midhordland district)

- South (Sørlandet)

- other dialects

- West (Vestlandet)

- Østlandsk (Eastern Norway)

- Flatbygd dialects (Lowland districts)

- Vikværsk dialects (Viken district)

- Drammen dialect (Drammen region)

- Follo dialect (Follo)

- Vestfold dialects (Vestfold)

- Tønsberg dialect (Tønsberg and Færder)

- Andebu dialect (Andebu)

- Revetal dialect (Re)

- Østfold dialects (Østfold)

- Fredrikstad dialect (Fredrikstad region)

- Inner Østfold dialect (Inner Østfold)

- Bohuslän dialect (Bohuslän province)

- Grenland dialect (Grenland district)

- Midtøstland dialects (Mid-east districts)

- Urban East Norwegian (Metropolitan area of Oslo)

- Oslo dialect (Oslo)

- Asker and Bærum dialect (Asker and Bærum)

- Romerike dialect (Romerike)

- Ringerike dialects (Ringerike district)

- Urban East Norwegian (Metropolitan area of Oslo)

- Oppland dialect (Opplandene district)

- Hedmark dialects (Hedmark)

- Hadeland dialect (Hadeland district)

- Østerdal dialect (Viken district)

- Särna-Idre dialect (Särna and Idre)

- Vikværsk dialects (Viken district)

- Midland dialects (Midland districts)

- Gudbrandsdal dialect (Gudbrandsdalen, Oppland and Upper Folldal, Hedmark)

- Hallingdal-Valdres dialects (Hallingdal, Valdres)

- Telemark-Numedal dialects (Telemark and Numedal)

- other dialects

- Flatbygd dialects (Lowland districts)

- Nordnorsk (Northern Norway)

Evolution

[edit]Owing to geography and climate, Norwegian communities were often isolated from each other until the early 20th century. As a result, local dialects had a tendency to be influenced by each other in singular ways while developing their own idiosyncrasies. Oppdal Municipality, for example, has characteristics in common with coastal dialects to the west, the dialects of northern Gudbrandsdalen to the south, and other dialects in Sør-Trøndelag from the north. The linguist Einar Haugen documented the particulars of the Oppdal dialect, and the writer Inge Krokann used it as a literary device. Other transitional dialects include the dialects of Romsdal and Arendal.

On the other hand, newly industrialized communities near sources of hydroelectric power have developed dialects consistent with the region but in many ways unique. Studies in such places as Høyanger, Odda, Tyssedal, Rjukan, Notodden, Sauda, and others show that koineization has effected the formation of new dialects in these areas.

Similarly, in the early 20th century a dialect closely approximating standard Bokmål arose in and around railway stations. This was known as stasjonsspråk ("station language") and may have contributed to changes in dialect around these centers.

Social dynamics

[edit]Until the 20th century, upward social mobility in a city like Oslo could in some cases require conforming speech to standard Riksmål. Studies show that even today, speakers of rural dialects may tend to change their usage in formal settings to approximate the formal written language. This has led to various countercultural movements ranging from the adoption of traditional forms of Oslo dialects among political radicals in Oslo, to movements preserving local dialects. There is widespread and growing acceptance that Norwegian linguistic diversity is worth preserving.

The trend today is a regionalisation of the dialects causing smaller dialectal traits to disappear and rural dialects to merge with their nearest larger dialectal variety.

There is no standard dialect for the Norwegian language as a whole, and all dialects are by now mutually intelligible. Hence, widely different dialects are used frequently and alongside each other, in almost every aspect of society. Criticism of a dialect may be considered criticism of someone's personal identity and place of upbringing, and is considered impolite. Not using one's proper dialect would be bordering on awkward in many situations, as it may signal a wish to take on an identity or a background which one does not have. Dialects are also an area from which to derive humour both in professional and household situations.

Distinctions

[edit]There are many ways to distinguish among Norwegian dialects. These criteria are drawn from the work Vårt Eget Språk/Talemålet (1987) by Egil Børre Johnsen. These criteria generally provide the analytical means for identifying most dialects, though most Norwegians rely on experience to tell them apart.

Grammars and syntax

[edit]Infinitive forms

[edit]One of the most important differences among dialects is which ending, if any, verbs have in the infinitive form. In Old Norwegian, most verbs had an infinitive ending (-a), and likewise in a modern Norwegian dialect, most of the verbs of the dialect either have or would have had an infinitive ending. There are five varieties of the infinitive ending in Norwegian dialects, constituting two groups:

One ending (western dialects)

- Infinitive ending with -a, e.g., å vera, å bita, common in southwestern Norway, including the areas surrounding Bergen (although not in the city of Bergen itself) and Stavanger (city)

- Infinitive ending with -e, e.g., å være, å bite, common in Troms, Finnmark, areas of Sogn og Fjordane and Møre og Romsdal, southern counties, and a few other areas.

- Apocopic infinitive, where no vowel is added to the infinitive form, e.g., å vær, å bit, common in certain areas of Nordland

Two different endings (eastern dialects)

- Split infinitive, in which some verbs end with -a while others end with -e; e.g. å væra versus å bite, common in Eastern Norway

- Split infinitive, with apocope, e.g., å væra (værra/vårrå/varra) versus å bit, common in some areas in Sør-Trøndelag and Nord-Trøndelag

The split distribution of endings is related to the syllable length of the verb in Old Norse. "Short-syllable" (kortstava) verbs in Norse kept their endings. The "long-syllable" (langstava) verbs lost their (unstressed) endings or had them converted to -e.

Dative case

[edit]The original Germanic contextual difference between the dative and accusative cases, standardized in modern German and Icelandic, has degenerated in spoken Danish and Swedish, a tendency which spread to Bokmål too. Ivar Aasen treated the dative case in detail in his work, Norsk Grammatik (1848), and use of Norwegian dative as a living grammatical case can be found in a few of the earliest Landsmål texts. However, the dative case has never been part of official Landsmål/Nynorsk.

It is, however, present in some spoken dialects north of Oslo, Romsdal, and south and northeast of Trondheim. The grammatical phenomenon is highly threatened in the mentioned areas, while most speakers of conservative varieties have been highly influenced by the national standard languages, using only the traditional accusative word form in both cases. Often, though not always, the difference in meaning between the dative and accusative word forms can thus be lost, requiring the speaker to add more words to specify what was actually meant, to avoid potential loss of information.

Future tense

[edit]There are regional variations in the use of future tense, for example, "He is going to travel.":

- Han kommer/kjem til å reise.

- Han blir å reise.

- Han blir reisan.

- Han skal reise.

Syntax

[edit]Syntax can vary greatly between dialects, and the tense is important for the listener to get the meaning. For instance, a question can be formed without the traditional "asking-words" (how, where, what, who..)

For example, the sentence Hvor mye er klokken? (in Bokmål), Kor mykje er klokka? (in Nynorsk), literally: "How much is the clock?" i.e. "What time is it?" can be put in, among others, the following forms:

- E klokka mykje? (Is the clock much?) (stress is on "the clock")

- E a mytti, klokka? (Is it much, the clock?) (stress on "is")

- Ka e klokka? (literally: "What is the clock?")

- Ka klokka e? (literally: What the clock is?), or, using another word for clock, Ke ure' e?

- Å er 'o? (literally: What is she?).

Pronunciation of vowels

[edit]Diphthongization of monophthongs

[edit]Old Norse had the diphthongs /au/, /ei/, and /øy/, but the Norwegian spoken in the area around Setesdal has shifted two of the traditional diphthongs and innovated four more from long vowels, and, in some cases, also short vowels.[2]

| Old Norse | Modern Norwegian |

|---|---|

| Setesdal[3] | |

| [ei] | [ai][2] |

| [øy] | [oy][2] |

| [iː] | [ei][2] |

| [yː] | [uy] |

| [uː] | [eu] |

| [oː] | [ou][2] |

West Norwegian dialects have also innovated new diphthongs. In Midtre[clarification needed] you can find the following:

| Old Norse | Modern Norwegian |

|---|---|

| Midtre | |

| [aː] | [au] |

| [oː] | [ou] |

| [uː] | [eʉ] |

Monophthongization of diphthongs

[edit]The Old Norse diphthongs /au/, /ei/, and /øy/ have experienced monophthongization in certain dialects of modern Norwegian.

| Old Norse | Modern Norwegian | |

|---|---|---|

| Urban East | Some dialects | |

| [ei] | [æɪ] | [e ~ eː] |

| [øy] | [œʏ] | [ø ~ øː] |

| [au] | [æʉ] | [ø ~ øː] |

This shift originated in Old East Norse, which is reflected in the fact that Swedish and Danish overwhelmingly exhibit this change. Monophthongization in Norway ends on the coast west of Trondheim and extends southeast in a triangle into central Sweden. Some Norwegian dialects, east of Molde, for example, have lost only /ei/ and /øy/.

Leveling

[edit](Jamning/Jevning in Norwegian) This is a phenomenon in which the root vowel and end vowel in a word approximate each other. For example, the old Norse viku has become våkkå or vukku in certain dialects. There are two varieties in Norwegian dialects – one in which the two vowels become identical, the other where they are only similar. Leveling exists only in inland areas in Southern Norway, and areas around Trondheim.

Vowel shift in strong verbs

[edit]In all but Oslo and coastal areas just south of the capital, the present tense of certain verbs take on a new vowel (umlaut), e.g., å fare becomes fer (in Oslo, it becomes farer).

Pronunciation of consonants

[edit]Eliminating /r/ in the plural indefinite form

[edit]In some areas, the /r/ is not pronounced in all or some words in their plural indefinite form. There are four categories:

- The /r/ is retained – most of Eastern Norway, the South-Eastern coast, and across to areas north and east of Stavanger.

- The /r/ disappears altogether – Southern tip of Norway, coastal areas north of Bergen, and inland almost to Trondheim.

- The /r/ is retained in certain words but not in others – coastal areas around Trondheim, and most of Northern Norway

- The /r/ is retained in certain words and in weak feminine nouns, but not in others – one coast area in Nordland.

Phonetic realization of /r/

[edit]Most dialects realize /r/ as the alveolar tap [ɾ] or alveolar trill [r]. However, for the last 200 years the uvular approximant [ʁ] has been gaining ground in Western and Southern Norwegian dialects, with Kristiansand, Stavanger, and Bergen as centers. The uvular R has also been adopted in aspiring patricians in and around Oslo, to the point that it was for some time fashionable to "import" governesses from the Kristiansand area. In certain regions, such as Oslo, the flap has become realized as a retroflex flap (generally called "thick L") /ɽ/, which exists only in Norway, a few regions in Sweden, and in completely unrelated languages. The sound coexists with other retroflexions in Norwegian dialects. In some areas it also applies to words that end with "rd," for example with gard (farm) being pronounced /ɡɑːɽ/. The uvular R has gained less acceptance in eastern regions, and linguists speculate that dialects that use retroflexes have a "natural defense" against uvular R and thus will not adopt it. However, the dialect of Arendal retains the retroflexes, while featuring the uvular R in remaining positions, e.g. rart [ʁɑːʈ].[citation needed]

In large parts of Northern Norway, especially in the northern parts of Nordland county and southern parts of Troms county, as well as several parts of Finnmark county, another variant is still common: the voiced post-alveolar sibilant fricative /ʒ/. In front of voiceless consonants, the realisation of this R is unvoiced as well, to /ʃ/. Thus, where one in the southern and Trøndelag dialects will get /sp̬ar̥k/ or /sp̬aʀk/ or /sp̬aʁ̥k/, in areas realising voiced R as /ʒ/, one will get /spaʃːk/.

Palatalization

[edit]In areas north of an isogloss running between Oslo and Bergen, palatalization occurs for the n (IPA [nʲ]), l ([lʲ]), t ([tʲ]) and d ([dʲ]) sounds in varying degrees. Areas just south and southwest of Trondheim palatalize both the main and subordinate syllable in words (e.g., [kɑlʲːɑnʲ]), but other areas only palatalize the main syllable ([bɑlʲ]).

Voicing of plosives

[edit]Voiceless stops (/p, t, k/) have become voiced ([b, d, ɡ]) intervocalically after long vowels (/ˈfløːdə/, /ˈkɑːɡə/ vs. /ˈfløːtə/, /ˈkɑːkə/) on the extreme southern coast of Norway, including Kristiansand, Mandal and Stavanger. The same phenomenon appears in Sør-Trøndelag[in which areas? The whole county?] and one area in Nordland.

Segmentation

[edit]The geminate /ll/ in southwestern Norway has become [dl], while just east in southcentral Norwegian the final [l] is lost, leaving [d]. The same sequence has been palatalized in Northern Norway, leaving the palatal lateral [ʎ].

Assimilation

[edit]The second consonant in the consonant clusters /nd/, /ld/, and /nɡ/ has assimilated to the first across most of Norway, leaving [n], [l], and [ŋ] respectively. Western Norway, though not in Bergen, retains the /ld/ cluster. In Northern Norway this same cluster is realized as the palatal lateral [ʎ].

Consonant shift in conjugation of masculine nouns

[edit]Although used less frequently, a subtle shift takes place in conjugating a masculine noun from indefinitive to definitive, e.g., from bekk to bekkjen ([becːen], [becçen], [beçːen] or [be:t͡ʃen]). This is found in rural dialects along the coast from Farsund Municipality to the border between Troms and Finnmark.

The kj - sj merger

[edit]Many people, especially in the younger generation, have lost the differentiation between the /ç/ (written ⟨kj⟩) and /ʂ/ (written ⟨sj⟩) sounds, realizing both as [ʂ]. This is by many considered to be a normal development in language change (although as most language changes, the older generation and more conservative language users often lament the degradation of the language). The functional load is relatively low, and as often happens, similar sounds with low functional loads merge.

Tonemes and intonation

[edit]There are great differences between the intonation systems of different Norwegian dialects.

Vocabulary

[edit]This section may be confusing or unclear to readers. In particular, all of the dialectal words should be transcribed in IPA. (January 2015) |

First person pronoun, nominative plural

[edit]Three variations of the first person plural nominative pronoun exist in Norwegian dialects:

- Vi, (pronounced /viː/), common in parts of Eastern Norway, most of Northern Norway, coastal areas close to Trondheim, and one sliver of Western Norway

- Me, mø or mi, in Southern and most of Western Norway, areas inland of Trondheim, and a few smaller areas

- Oss, common in areas of Sør-Trøndelag, Gudbrandsdalen, Nordmøre and parts of Sunnmøre.

First person pronoun, nominative singular

[edit]There is considerable variety in the way the first person singular nominative pronoun is pronounced in Norwegian dialects. They appear to fall into three groups, within which there are also variations:

- E(g) and æ(i)(g), in which the hard 'g' may or may not be included. This is common in most of Southern and Western Norway, Trøndelag, and most of Northern Norway. In some areas of Western Norway, it is common to say ej.

- I (pronounced /iː/), in a few areas in Western Norway (Romsdal/Molde) and Snåsa in Trøndelag

- Jé [je(ː)], jè [jɛ(ː)], or jei [jɛi(ː)], in areas around Oslo, and north along the Swedish border, almost to Trondheim, as well as one region in Troms

Personal pronouns

[edit]| Regions | I | You | He | She | It | We | You (pl.) | They |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bokmål | Jeg | Du | Han | Hun | Det | Vi | Dere | De, dem |

| Nynorsk | Eg | Du | Han | Ho | Det | Vi, me | De, dykk, dokker | Dei |

| South Eastern Norway | Jæ, jé, jè, jei | Du, ru, u, dø | Han, hæn, hænnom, hannem | Hun, ho, hu, ha, a, henne, henner | De | Vi, ve, mø, oss, øss, æss, vårs | Dere, dø, de, di, døkk, dår(e), dør(e) | Dem, rem, 'rdem, em, døm, dom, di |

| Most of Western and Southern Norway | Eg, e, æ, æg, æi, æig, jei, ej, i | Du, dø, døø, døh | Han, an, ha'an | Hun, ho, hu, hau, hon, u | De, da, d' | Vi, me, mi, mø, åss | Dere, då(k)ke, dåkkar, dåkk, de, derr, dåkki, dikko(n), deke, deko, | De, dei, dæ, di, di'i |

| Trøndelag and most of Northern Norway | Æ, æg, i, eig, jæ, e, eg | Du, dæ, dø, u, dæ'æ | Han, hanj, hin, hån | Hun, hu, ho, a | De, da, dæ, e, denj, ta | Vi, åss, oss, åkke, me, mi | Dåkk, dåkke, dåkker, dåkkæ, dere, ere, dykk, di | Dei, dem, dæm, 'em, di, r'ej, dåm |

Possessive pronouns

[edit]| Regions | My | Your | His | Her | Its | Our | Your (pl.) | Their |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bokmål | Min, mi, mitt | Din, di, ditt | Hans | Hennes | dens, dets | Vår | Deres | Deres |

| Nynorsk | Min, mi, mitt | Din, di, ditt | Hans | Hennar | Rarely used. When used: dess | Vår | Dykkar | Deira |

| South Eastern Norway | Min, mi, mitt, mø | Din, di, ditt | Hans, hannes, hanns, hass | Hennes, henners, hun sin, hos, hinnes | Dets, det sitt | Vårs, vørs, vår, 'år, våres | Deres, døres, | Dems, demmes, demma, demses, dem sitt, dommes, doms, døms |

| Most of Western and Southern Norway | Min, mi, mitt | Din, di, ditt | Hans, hannes, hannas, høns, hønnes, ans | Hennes,hons, hos, hosses, høvs, haus, hennar, hen(n)as, nas | nonexistent or dens, dets | Vår, 'år, våres, våras, åkkas, åkka, aokan(s) | Deres, dokkas, dokkar(s), dåkas, dekan, dekans | Demmes, dies, dis, deisa, deis, daus, døvs, deira,

deira(n)s |

| Trøndelag and most of Northern Norway | Min, mi, mitt, mæjn, mett | Din, di, ditt, dij, dej'j | Hans, hannjes, hanses, hannes, hanner, hånner | Hennes, hennjes, hunnes, henna, hennar, huns | Dets, det sitt, dess | Vår, våkke, vår', våres, vårres | Deres, dokkers, dokkes, 'eras | Dems, demma, dæres, dæmmes, dæmmers, deira |

The word "not"

[edit]The Norwegian word for the English not exists in these main categories:

- ikke [ikːə] – Oslo, Kristiansand, Bergen, Ålesund, most of Finnmark, Vestfold and lowland parts of Telemark, and some cities in Nordland.

- ikkje [içːə/iːt͡ʃə] – most of Southern, Northern, Western Norway and high-land parts of Telemark.

- ittj [itʲː] – Trøndelag

- ikkj [içː] - parts of Salten District, Nordland

- itte [iːtə] or ittje [itʲːə] – areas north of Oslo, along the Swedish border

- inte [intə], ente [entə] or ette [etːə] – Mostly along the Swedish border south of Oslo in Østfold

- kje/e'kje

- isje/itsje

Examples of the sentence "I am not hungry," in Norwegian:

- ikke: Jeg er ikke sulten. (Bokmål)

- ikkje: Eg er ikkje svolten. (Nynorsk)

- ikkje: I e ikkje sulten. (Romsdal)

- ittj: Æ e ittj sopin. (Trøndelag)

- ikkj: E e ikkj sulten. (Salten)

- ke: Æ e ke sulten. (Narvik)

- ente: Je er'nte sulten. (Hærland)

Interrogative words

[edit]Some common interrogative words take on forms such as:

| Regions | who | what | where | which | how | why | when |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bokmål | hvem | hva | hvor | hvilken, hvilket, hvilke | hvordan, hvorledes, åssen | hvorfor | når |

| Nynorsk | kven | kva | kor, kvar | kva for ein/ei/eit | korleis, korso | kvifor, korfor | når, kva tid |

| South Eastern Norway | hvem, åkke, åkkjen, høkken, håkke | hva, å da, å, hø da, hå, hæ, hær | hvor, hvorhen, å hen, å henner, hen, hørt, hærre, håppæs, hæppæs | hvilken, hvilke, åkken, åssen, hvem, hva slags, hø slags, hæsse, håssen. håleis, hådan | hvordan, åssen, høssen, hæsse | hvorfor, åffer, å for, høffer, hæffer | ti, å ti, når, hærnér |

| Most of Western Norway | kven, ken, kin, kem, kim | kva, ka, ke, kæ, kå | kor, kest, korhen/korhenne, hen | kva, ka, kvaslags, kaslags, kasla, kallas, kalla, kass, kvafor, kafor, kaforein, keslags, kæslags, koffø en | kordan, korsn, korleis, karleis, koss, koss(e)n | korfor, koffor, kvifor, kafor, keffår, koffø | når, ti, kati, korti, koti, kå ti |

| Trøndelag and most of Northern Norway | kæm, kem, kånn, kenn | ka, ke, kve, ker | kor, korhæn/korhænne, ker, karre, kehænn | kolles, koss, korsn, kossn, kasla, kass, kafor, kafør, kåfår, kersn, kess, kafla | kolles, koss, kess, korsn, kossn, kordan, korran, kelles | korfor, kafor, kafør, koffer, koffør, koffår, kåffår, keffer | når, ner, nå, når ti, ka ti, katti, kåtti |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Martin Skjekkeland. "dialekter i Norge". Store norske leksikon. Retrieved February 1, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e "dialekter i Setesdal - Store norske leksikon". Retrieved 4 January 2015. Authors state that the Setesdal dialect is "perhaps the most distinctive and most difficult to understand" among all Norwegian dialects.

- ^ To hear them pronounced, go to "Talemålet i Valle og Hylestad". Retrieved 4 January 2015. The section Uttale av vokalane needs to be selected manually.

Sources

[edit]- Jahr, Ernst Håkon (1990) Den Store dialektboka (Oslo: Novus) ISBN 8270991678

- Kristoffersen, Gjert (2000) The Phonology of Norwegian (Oxford University Press) ISBN 978-0-19-823765-5

- Vanvik, Arne (1979) Norsk fonetikk (Oslo: Universitetet i Oslo) ISBN 82-990584-0-6

Further reading

[edit]- Vikør, Lars S. (2001) The Nordic languages. Their Status and Interrelations (Oslo: Novus Press) ISBN 82-7099-336-0

- Johnsen, Egil Børre (1987) Vårt Eget Språk/Talemålet (H. Aschehoug & Co.) ISBN 82-03-17092-7

External links

[edit]- Norwegian Language Council

- Measuring the "distance" between the Norwegian dialects

- En norsk dialektprøvedatabase på nettet, a Norwegian database of dialect samples.

- [1], introduction to Northern Norwegian dialects written in English