Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Numic languages

View on Wikipedia| Numic | |

|---|---|

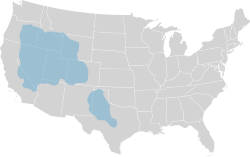

| Geographic distribution | Western United States |

| Linguistic classification | Uto-Aztecan

|

| Subdivisions |

|

| Language codes | |

| Glottolog | numi1242 |

| |

Numic is the northernmost branch of the Uto-Aztecan language family. It includes seven languages spoken by Native American peoples traditionally living in the Great Basin, Colorado River basin, Snake River basin, and southern Great Plains. The word "Numic" comes from the cognate word in all Numic languages for "person", which reconstructs to Proto-Numic as /*nɨmɨ/. For example, in the three Central Numic languages and the two Western Numic languages, the word for "person" is /nɨmɨ/. In Kawaiisu it is /nɨwɨ/, and in Colorado River, it is /nɨwɨ/, /nɨŋwɨ/, and /nuu/.

Classification

[edit]

These languages are classified in three groups:

Apart from Comanche, each of these groups contains one language spoken in a small area in the southern Sierra Nevada and valleys to the east (Mono, Timbisha, and Kawaiisu), and one language spoken in a much larger area extending to the north and east (Northern Paiute, Shoshoni, and Colorado River). Some linguists have taken this pattern as an indication that Numic speaking peoples expanded quite recently from a small core, perhaps near the Owens Valley, into their current range. This view is supported by lexicostatistical studies.[22] Fowler's reconstruction of Proto-Numic ethnobiology also points to the region of the southern Sierra Nevada as the homeland of Proto-Numic approximately two millennia ago.[23] A mitochondrial DNA study from 2001 supports this linguistic hypothesis.[24] The anthropologist Peter N. Jones thinks this evidence to be of a circumstantial nature,[25] but this is a distinctly minority opinion among specialists in Numic.[26] David Shaul has proposed that the Southern Numic languages spread eastward long before the Central and Western Numic languages expanded into the Great Basin.[27]

Bands of eastern Shoshoni split off from the main Shoshoni body in the very late 17th or very early 18th century and moved southeastward onto the Great Plains.[28] Changes in their Shoshoni dialect eventually produced Comanche. The Comanche language and the Shoshoni language are quite similar although certain low-level consonant changes in Comanche have inhibited mutual intelligibility.[29]

Recent lexical and grammatical diffusion studies in Western Numic have shown that while there are clear linguistic changes that separate Northern Paiute as a distinct linguistic variety, there are no unique linguistic changes that mark Mono as a distinct linguistic variety.[30]

Major sound changes

[edit]The sound system of Numic is set forth in the following tables.[31]

Vowels

[edit]Proto-Numic had an inventory of five vowels.

| front | back unrounded |

back rounded | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | *i | *ɨ | *u |

| Non-High | *a | *o |

Consonants

[edit]Proto-Numic had the following consonant inventory:

| Bilabial | Coronal | Palatal | Velar | Labialized velar |

Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop | *p | *t | *k | *kʷ | *ʔ | |

| Affricate | *ts | |||||

| Fricative | *s | *h | ||||

| Nasal | *m | *n | *ŋ | (*ŋʷ) | ||

| Semivowel | *j | *w |

In addition to the above simple consonants, Proto-Numic also had nasal-stop/affricate clusters and all consonants except *s, *h, *j, and *w could be geminated. Between vowels short consonants were lenited.

Major Central Numic consonant changes

[edit]The major difference between Proto-Central Numic and Proto-Numic was the phonemic split of Proto-Numic geminate consonants into geminate consonants and preaspirated consonants. The conditioning factors involve stress shifts and are complex. The preaspirated consonants surfaced as voiceless fricatives, often preceded by a voiceless vowel.

Shoshoni and Comanche have both lost the velar nasals, merging them with *n or turning them into velar nasal-stop clusters. In Comanche, nasal-stop clusters have become simple stops, but p and t from these clusters do not lenite intervocalically. This change postdates the earliest record of Comanche from 1786, but precedes the 20th century. Geminated stops in Comanche have also become phonetically preaspirated.

Major Southern Numic consonant changes

[edit]Proto-Southern Numic preserved the Proto-Numic consonant system fairly intact, but the individual languages have undergone several changes.

Modern Kawaiisu has reanalyzed the nasal-stop clusters as voiced stops, although older recordings preserve some of the clusters. Geminated stops and affricates are voiceless and non-geminated stops and affricates are voiced fricatives. The velar nasals have fallen together with the alveolar nasals.

The dialects of Colorado River east of Chemehuevi have lost *h. The dialects east of Kaibab have collapsed the nasal-stop clusters with the geminated stops and affricate.

Major Western Numic consonant changes

[edit]Proto-Western Numic changed the nasal-stop clusters of Proto-Numic into voiced geminate stops. In Mono and all dialects of Northern Paiute except Southern Nevada, these voiced geminate stops have become voiceless.

Sample Numic cognate sets

[edit]The following table shows some sample Numic cognate sets that illustrate the above changes. Forms in the daughter languages are written in a broad phonetic transcription rather than a phonemic transcription that sometimes masks the differences between the forms. Italicized vowels and sonorants are voiceless.

| Mono | Northern Paiute | Timbisha | Shoshoni | Comanche | Kawaiisu | Colorado River | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *hoa 'hunt, trap' |

hoa | hoa | hɨwa | hɨa | hɨa | hɨa | oa (SP) 'spy' |

| *jaka 'cry' |

jaɣa | jaɣa | jaɣa | jaɣai | jake | jaɣi | jaɣa |

| *kaipa 'mountain' |

kaiβa | kaiβa | keeβi | kaiβa | |||

| *kuttsu 'bison' |

kuttsu | kuttsu 'cow' |

kwittʃu 'cow' |

kuittʃun 'cow' |

kuhtsu 'cow' |

kuttsu | |

| *naŋka 'ear' |

nakka | nakka naɡɡa (So Nev) |

naŋɡa | naŋɡi | naki | naɣaβiβi | naŋkaβɨ (Ch) nakka- (Ut) |

| *oppimpɨ 'mesquite' |

oɸimbɨ | oɸi 'mesquite bean' |

oβi(m)bɨ | oppimpɨ (Ch) | |||

| *paŋkʷi 'fish' |

pakkʷi | pakkʷi paɡɡʷi (So Nev) |

paŋŋʷi | paiŋɡʷi | pekʷi | ||

| *puŋku 'pet, dog' |

pukku | pukku puɡɡu (So Nev) 'horse' |

puŋɡu 'pet' |

puŋɡu 'horse' |

puku 'horse' |

puɣu | puŋku (Ch) pukku (Ut) 'pet' |

| *tɨpa 'pine nut' |

tɨβa | tɨβa | tɨβa | tɨβa | tɨβattsi | tɨβa | |

| *woŋko 'pine' |

wokkoβɨ | wokkoppi oɡɡoppi (So Nev) |

woŋɡoβi | woŋɡoβin | wokoβi | woɣo- (only in compounds) |

oɣompɨ |

References

[edit]- ^ John E. McLaughlin. 1992. “A Counter-Intuitive Solution in Central Numic Phonology,” International Journal of American Linguistics 58:158–181.

John E. McLaughlin. 2000. “Language Boundaries and Phonological Borrowing in the Central Numic Languages,” Uto-Aztecan: Temporal and Geographical Perspectives. Ed. Gene Casad and Thomas Willett. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. Pp. 293–304.

Wick Miller, Dirk Elzinga, and John E. McLaughlin. 2005. "Preaspiration and Gemination in Central Numic," International Journal of American Linguistics 71:413–444.

John E. McLaughlin. 2023. Central Numic (Uto-Aztecan) Comparative Phonology and Vocabulary. LINCOM Studies in Native American Linguistics 86. Munich, Germany: LINCOM GmbH. - ^ Lila Wistrand Robinson & James Armagost. 1990. Comanche Dictionary and Grammar. Summer Institute of Linguistics and The University of Texas at Arlington Publications in Linguistics Publication 92. Dallas, Texas: The Summer Institute of Linguistics and The University of Texas at Arlington.

Jean O. Charney. 1993. A Grammar of Comanche. Studies in the Anthropology of North American Indians. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press.

Anonymous. 2010. Taa Nʉmʉ Tekwapʉ?ha Tʉboopʉ (Our Comanche Dictionary). Elgin, Oklahoma: Comanche Language and Cultural Preservation Committee. - ^ Jon P. Dayley. 1989. Tümpisa (Panamint) Shoshone Grammar. University of California Publications in Linguistics Volume 115. Berkeley, California: University of California Press.

Jon P. Dayley. 1989. Tümpisa (Panamint) Shoshone Dictionary. University of California Publications in Linguistics Volume 116. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. - ^ John E. McLaughlin. 2006. Timbisha (Panamint). Languages of the World/Materials 453. Muenchen: LINCOM Europa.

- ^ John E. McLaughlin. 2012. Shoshoni Grammar. Languages of the World/Materials 488. Muenchen: LINCOM Europa.

- ^ Richley H. Crapo. 1976. Big Smokey Valley Shoshoni. Desert Research Institute Publications in the Social Sciences 10. Reno: University of Nevada Press.

Beverly Crum & Jon Dayley. 1993. Western Shoshoni Grammar. Boise State University Occasional Papers and Monographs in Cultural Anthropology and Linguistics Volume No. 1. Boise, Idaho: Department of Anthropology, Boise State University. - ^ Wick R. Miller. 1972. Newe Natekwinappeh: Shoshoni Stories and Dictionary. University of Utah Anthropological Papers 94. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press.

Wick R. Miller. 1996. "Sketch of Shoshone, a Uto-Aztecan Language," Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 17, Languages. Ed. Ives Goddard. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. Pages 693–720.

Dirk Allen Elzinga. 1999. "The Consonants of Gosiute", University of Arizona Ph.D. dissertation. - ^ Drusilla Gould & Christopher Loether. 2002. An Introduction to the Shoshoni Language: Dammen Daigwape. Salt Lake City, Utah: The University of Utah Press.

- ^ D.B. Shimkin. 1949. "Shoshone, I: Linguistic Sketch and Text," International Journal of American Linguistics 15:175–188.

D. B. Shimkin. 1949. "Shoshone II: Morpheme List," International Journal of American Linguistics 15.203–212.

Malinda Tidzump. 1970. Shoshone Thesaurus. Grand Forks, North Dakota. - ^ Maurice L. Zigmond, Curtis G. Booth, & Pamela Munro. 1991. Kawaiisu, A Grammar and Dictionary with Texts. Ed. Pamela Munro. University of California Publications in Linguistics Volume 119. Berkeley, California: University of California Press.

- ^ Margaret L. Press. 1979. Chemehuevi, A Grammar and Lexicon. University of California Publications in Linguistics Volume 92. Berkeley, California. University of California Press.

Laird, Carobeth. 1976. The Chemehuevis. Malki Museum Press, Banning, California. - ^ Edward Sapir. 1930. Southern Paiute, a Shoshonean Language. Reprinted in 1992 in: The Collected Works of Edward Sapir, X, Southern Paiute and Ute Linguistics and Ethnography. Ed. William Bright. Berlin: Mouton deGruyter.

Edward Sapir. 1931. Southern Paiute Dictionary. Reprinted in 1992 in: The Collected Works of Edward Sapir, X, Southern Paiute and Ute Linguistics and Ethnography. Ed. William Bright. Berlin: Mouton deGruyter.

Pamela A. Bunte. 1979. "Problems in Southern Paiute Syntax and Semantics," Indiana University Ph.D. dissertation. - ^ Talmy Givón. 2011. Ute Reference Grammar. Culture and Language Use Volume 3. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Jean O. Charney. 1996. A Dictionary of the Southern Ute Language. Ignacio, Colorado: Ute Press. - ^ Molly Babel, Andrew Garrett, Michael J. House, & Maziar Toosarvandani. 2013. "Descent and Diffusion in Language Diversification: A Study of Western Numic Dialectology," International Journal of American Linguistics 79:445–489.

- ^ Sidney M. Lamb. 1957. "Mono Grammar," University of California, Berkeley Ph.D. dissertation.

Rosalie Bethel, Paul V. Kroskrity, Christopher Loether, & Gregory A. Reinhardt. 1993. A Dictionary of Western Mono. 2nd edition. - ^ Evan J. Norris. 1986. "A Grammar Sketch and Comparative Study of Eastern Mono," University of California, San Diego Ph.D. dissertation.

- ^ Sven Liljeblad, Catherine S. Fowler, & Glenda Powell. 2012. The Northern Paiute–Bannock Dictionary, with an English–Northern Paiute–Bannock Finder List and a Northern Paiute–Bannock–English Finder List. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press.

- ^ Anonymous. 1987. Yerington Paiute Grammar. Anchorage, Alaska: Bilingual Education Services.

Arie Poldevaart. 1987. Paiute–English English–Paiute Dictionary. Yerington, Nevada: Yerington Paiute Tribe. - ^ Allen Snapp, John Anderson, & Joy Anderson. 1982. "Northern Paiute," Studies in Uto-Aztecan Grammar, Volume 3, Uto-Aztecan Grammatical Sketches. Ed. Ronald W. Langacker. Summer Institute of Linguistics Publications in Linguistics Publication Number 57, Volume III. Dallas, Texas: Summer Institute of Linguistics and The University of Texas at Arlington. Pages 1–92.

- ^ Timothy John Thornes. 2003. "A Northern Paiute Grammar with Texts," University of Oregon Ph.D. dissertation.

- ^ Sven Liljeblad. 1966–1967. "Northern Paiute Lessons," manuscript.

Sven Liljeblad. 1950. "Bannack I: Phonemes," International Journal of American Linguistics 16:126–131 - ^ James A. Goss. 1968. "Culture-Historical Inference from Utaztekan Linguistic Evidence," Utaztekan Prehistory. Ed. Earl H. Swanson, Jr. Occasional Papers of the Idaho State University Museum, Number 22. Pages 1–42.

- ^ Catherine Louise Sweeney Fowler. 1972. "Comparative Numic Ethnobiology". University of Pittsburgh PhD dissertation.

- ^ Frederika A. Kaestle and David Glenn Smith. 2001. "Ancient Mitochondrial DNA Evidence for Prehistoric Population Movement," American Journal of Physical Anthropology 115:1–12.

- ^ Peter N. Jones. 2005. Respect for the Ancestors: American Indian Cultural Affiliation in the American West. Boulder, CO: Bauu Institute.

- ^ David B. Madsen & David Rhode, ed. 1994. Across the West: Human Population Movement and the Expansion of the Numa. University of Utah Press.

- ^ David Leedom Shaul. 2014. A Prehistory of Western North America, The Impact of Uto-Aztecan Languages. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

- ^ Thomas W. Kavanagh. 1996. The Comanches, A History 1706-1875. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- ^ John E. McLaughlin. 2000. “Language Boundaries and Phonological Borrowing in the Central Numic Languages,” Uto-Aztecan: Temporal and Geographical Perspectives. Ed. Gene Casad and Thomas Willett. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. Pp. 293–304.

- ^ Molly Babel, Andrew Garrett, Michael J. House, & Maziar Toosarvandani. 2013. "Descent and Diffusion in Language Diversification: A Study of Western Numic Dialectology," International Journal of American Linguistics 79:445–489.

- ^ David Iannucci. 1972. "Numic historical phonology," Cornell University PhD dissertation.

Michael Nichols. 1973. "Northern Paiute historical grammar," University of California, Berkeley PhD dissertation

Wick R. Miller. 1986. "Numic Languages," Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 11, Great Basin. Ed. by Warren L. d’Azevedo. Washington: Smithsonian Institution. Pages 98–106.

Numic languages

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition and Etymology

The Numic languages form the northernmost branch of the Uto-Aztecan language family, consisting of seven closely related languages primarily spoken by Indigenous peoples across western North America, from the Great Basin to the Colorado Plateau and adjacent regions.[2][1] These languages are characterized by their genetic unity and shared innovations, distinguishing them from other Uto-Aztecan subgroups.[1] The term "Numic" was introduced by linguist Sidney M. Lamb in his 1958 dissertation on Mono grammar to designate this branch, drawing from the reconstructed Proto-Numic form *nɨmɨ, which means "person."[4] This etymology follows a self-referential naming pattern observed in several Uto-Aztecan branches, where designations for linguistic groups often stem from indigenous terms for "person" or "people," emphasizing ethnic and cultural identity.[4] To contextualize Numic's role, the broader Uto-Aztecan family includes over 40 languages distributed from the western United States through northern Mexico, with Numic occupying the northern periphery of this expansive genetic unit.[5]Place in Uto-Aztecan Family

The Numic languages constitute a well-established genetic subgroup within the Uto-Aztecan language family, representing its northernmost extension and encompassing languages spoken across the Great Basin and adjacent regions. This clade was initially recognized as a distinct branch by Alfred L. Kroeber in 1907, who identified lexical similarities among what he termed "Plateau Shoshonean" dialects, setting them apart from other Uto-Aztecan varieties.[6] Subsequent comparative work by Edward Sapir, including his 1915 analysis of Southern Paiute (a Numic language) alongside Nahuatl, reinforced Numic's position by demonstrating systematic phonological and lexical correspondences that unified it with the broader family while highlighting internal innovations. Evidence for Numic unity derives primarily from shared phonological and grammatical innovations that differentiate it from southern branches like Nahuan (Aztecan) and Taracahitan. A key phonological shift involves the merger of Proto-Uto-Aztecan *r with *n in Proto-Numic, leading to the loss of a distinct liquid phoneme in medial positions.[7] Pronominal systems exhibit consistent innovations, such as the development of dual forms alongside singular and plural, with inclusive/exclusive distinctions in first-person pronouns (e.g., Proto-Numic *nü- 'we inclusive dual' vs. *mü- 'we exclusive'), features less prominent in southern Uto-Aztecan.[2] Grammatical markers like dual number on nouns, realized through suffixes such as *-tsi in Central Numic (e.g., Panamint *pahi-ttsi 'two waters'), further underscore this coherence, evolving from Proto-Uto-Aztecan analytic constructions.[8] Lexical evidence includes innovations in core vocabulary, particularly kinship terms, where Proto-Numic reconstructions show semantic shifts and assimilations not retained elsewhere; for instance, *kuma 'husband' reflects nasal assimilation from an earlier *kuŋa, contrasting with Takic kúŋlu or Tepiman kun.[9] These shared items, alongside retentions like *pa:vi 'water' (cognate across Numic but with distinct reflexes in southern Uto-Aztecan branches such as Nahuatl ātl), distinguish Numic from southern clades.[7] Debates persist regarding Numic's deeper affiliations within Uto-Aztecan, with most scholars aligning it to a Northern Uto-Aztecan node alongside Takic, Tubatulabal, and Hopi, based on innovations like the affricate shift *c > y (e.g., Numic *ya: 'go' from PUA *ca).[10] This proximity is evident in higher cognate densities with Takic (around 45-55%) than with southern branches (30-40%). Lexicostatistical analyses confirm Numic's internal cohesion, with average cognate retention of 60-70% among its languages (e.g., 68% between Shoshone and Paiute on a 200-item list), dropping to 40-50% with Tubatulabal or Takic, supporting its status as a primary clade.[11]Classification

Branches of Numic

The Numic languages are classified into three primary branches: Western Numic, comprising two languages (Mono and Northern Paiute); Central Numic, with three languages (Timbisha, Shoshoni, and Comanche); and Southern Numic, consisting of two languages (Kawaiisu and Ute-Southern Paiute).[12] This tripartite division is supported by shared phonological isoglosses and lexical innovations that distinguish the branches from one another and from the broader Uto-Aztecan family.[3] For instance, the treatment of Proto-Uto-Aztecan *kʷ shows variation across branches, with Western Numic often modifying or losing the labiovelar quality, Central Numic developing preaspirated forms, and Southern Numic retaining it more faithfully.[13] Evidence for this branching includes branch-specific phonological developments and lexical items. Western Numic is defined by the early loss of nasalization on prenasalized segments, resulting in voiced fortis stops (e.g., *mp > bb), alongside the preservation of certain obstruentized sounds from Proto-Numic *ɲy and *ŋw.[12] Central Numic features the innovation of preaspiration in the geminate consonant series (e.g., distinguishing geminated from preaspirated stops), often accompanied by vowel shifts like *ai > e.[1] Southern Numic, in contrast, preserves consonant clusters that simplified elsewhere, such as maintaining complex onsets from Proto-Numic.[3] Lexical innovations further bolster these distinctions, including Western-specific terms like *nobi 'house' and Southern retentions like toyabi 'mountain,' derived from shared but diverged Proto-Numic roots.[12] Glottochronological analysis, based on cognate retention rates in basic vocabulary lists, estimates the divergence of these branches from Proto-Numic around 1,500 to 2,000 years ago.[12] Within the branches, internal genetic relationships reflect varying degrees of dialectal continuity. Central Numic forms a tight subgroup, with Shoshoni and Comanche constituting a dialect continuum marked by gradual phonological and lexical shifts across their geographic range.[1] Southern Numic exhibits dialectal variation, particularly in Ute-Southern Paiute, where regional differences in vowel harmony and suffixation create a chain of mutually intelligible varieties but distinct from Kawaiisu.[12] These patterns underscore the role of geographic proximity in shaping subgroup cohesion while maintaining the overall branch-level separations.[3]Individual Languages

The Numic languages are divided into three branches: Western, Central, and Southern, each comprising distinct languages with varying dialects and speaker populations as of the 2020s. All seven languages are classified as endangered, reflecting low speaker numbers and limited intergenerational transmission.[14] In the Western Numic branch, Mono (also known as Monache) includes two main varieties: Western Mono, traditionally spoken in the Yosemite area of central California, and Eastern Mono in the Owens Valley region. The language has approximately 50 speakers, primarily older adults. Northern Paiute (also called Numu or Paviotso), the other Western Numic language, features a dialect continuum spanning Nevada, Oregon, and Idaho, with notable varieties such as Bannock and Snake. It has between 400 and 700 speakers as of the 2020s, concentrated among elders but with some use by younger community members.[15] The Central Numic branch encompasses Timbisha (also referred to as Panamint Shoshone), spoken in the Death Valley area of California and Nevada, with fewer than 50 speakers remaining, mostly elderly. Shoshoni (or Shoshone) includes several dialects across Wyoming, Idaho, and Nevada, such as Gosiute and Western Shoshone, with fewer than 200 speakers as of 2024.[16] Comanche, a Plains variety derived from Shoshoni, is spoken primarily in southwestern Oklahoma, with fewer than 50 fluent speakers as of 2024.[17][18][19][20] Southern Numic consists of Kawaiisu, spoken in the Tehachapi Mountains region of southern California, with fewer than 10 speakers, including just one fluent elder as of recent records. Ute-Southern Paiute forms a dialect continuum that includes Uintah Ute in Utah, Southern Paiute in Utah, Nevada, and Arizona, Chemehuevi in California and Arizona, and Kaibab Paiute, with a total of 1,500 to 2,000 speakers across these varieties.[21][22] According to UNESCO's Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger, all Numic languages are endangered or critically endangered due to declining speaker bases and external pressures on indigenous communities. Revitalization efforts vary, with notable programs for Northern Paiute including community-led classes and digital documentation initiatives at institutions like the University of California, Santa Cruz, aimed at preserving dialects and teaching younger generations.[23]Historical and Cultural Context

Origins and Expansion

The proposed homeland of Proto-Numic speakers is located in the southern Sierra Nevada and Owens Valley region of eastern California, based on linguistic paleontology that reconstructs vocabulary for local flora and fauna, such as terms for pinyon pine (*wáhi) and riparian plants indicative of a diverse, elevated desert environment.[24] Glottochronological estimates place the emergence of Proto-Numic around 2,500 years ago, with the split from other Northern Uto-Aztecan branches, including Takic, occurring approximately 2,500–3,200 years ago, supporting an initial development in this southern area before broader dispersal.[25] The expansion of Numic speakers involved a rapid northward and eastward spread across the Great Basin beginning around 500–1000 CE (with scholarly debate favoring ca. 600–1000 CE based on recent evidence), correlating with the arrival of Numic peoples who displaced or assimilated pre-existing populations, potentially including Hokan-speaking groups like the Washoe.[24] This movement is modeled as a replacement or competitive expansion driven by adaptive foraging strategies, such as intensified pinyon nut exploitation (though early vs. late timing remains debated), which provided a demographic advantage over sedentary foragers in the region.[26][24] Archaeological evidence supports this timeline through shifts in material culture, including the appearance of Desert Side-notched projectile points and increased pinyon processing sites dated to 600–1300 CE in the Owens Valley and adjacent areas.[24] Genetic data from mitochondrial DNA further corroborates southern origins, with haplogroup C—prevalent among modern Numic groups but rare in other Great Basin populations—identified in remains from sites like Fish Slough Cave (dated 840–1180 CE) and Stillwater Marsh (840–1180 BP), indicating population replacement approximately 1,000–1,300 years ago.[27] Within the Central Numic branch, Comanche diverged from Shoshoni in the late 17th to early 18th centuries, following a migration from the Rocky Mountains to the southern Plains around 1700 CE, where acquisition of horses accelerated linguistic and cultural differentiation.[28][29]Associated Peoples and Cultures

The Numic languages are spoken by several Indigenous peoples across the western United States, each with distinct cultural identities shaped by their environments and historical practices. In the Western Numic branch, the Mono people, known as Monache, were hunter-gatherers inhabiting the foothills and higher elevations of the Sierra Nevada, relying on deer hunting, acorn gathering, and seasonal foraging for sustenance.[30][31] The Northern Paiute, or Numu, practiced foraging in the Great Basin, undertaking seasonal migrations to exploit resources like piñon nuts, roots, seeds, game, and fish, with subgroups often named after primary food sources such as trout.[32] Central Numic languages are associated with groups adapted to diverse arid and plateau landscapes. The Timbisha, or Death Valley Shoshone, developed lifeways suited to extreme desert valleys stretching from Owens Lake to Death Valley, where small family groups navigated harsh conditions through resourceful gathering and hunting.[2] The Shoshoni, self-identified as Newe or "The People," maintained a widespread presence in the Basin-Plateau culture area, emphasizing communal foraging, pine nut harvesting, and social structures tied to extended family networks across Nevada, Idaho, and Wyoming.[33] The Comanche, known as Padouuk or "Snake People," transitioned to an equestrian Plains culture after acquiring horses around 1650 from Spanish and Pueblo sources, becoming renowned for mounted warfare, buffalo hunting, and nomadic raiding bands that dominated the southern Plains by the 1700s.[34] Southern Numic speakers include the Kawaiisu, who lived as desert-edge hunters and gatherers along the southern Sierra Nevada, Tehachapi Mountains, and Piute Mountains in southern California, focusing on small-game pursuits and plant collection in semi-arid zones.[35] The Ute and Southern Paiute, with the latter collectively referred to as Nuwu or "The People" in Southern Paiute, inhabited mountain ranges, river valleys, and plateaus in Utah, Colorado, Nevada, and Arizona, adapting through riverine fishing, highland hunting, and renowned basketry traditions that produced coiled and twined vessels for storage, cooking, and ceremony.[36][37] These languages encode profound cultural-linguistic ties, preserving oral traditions such as Shoshoni Coyote myths that recount tribal dispersals, moral lessons, and connections to sacred landscapes like Owens Valley and Death Valley.[38] Place names in Numic tongues reflect environmental knowledge and historical events, while ceremonies like Paiute mourning rituals draw on shared narratives of migration and renewal.[38] European colonization severely disrupted these practices, imposing reservations, resource exploitation from gold rushes, and assimilation policies that accelerated language shift, reducing fluent speakers and integrating communities into wage labor and ranching economies.[32][39]Geographic Distribution

Traditional Territories

The traditional territories of Numic languages formed a core in the Great Basin, encompassing much of present-day Nevada, Utah, eastern California, western Colorado, southern Idaho, and northern Arizona.[40] This expansive region, characterized by its inland drainage and isolation, supported Numic-speaking peoples through diverse ecological niches ranging from desert valleys to montane forests.[41] Numic territories were divided among its three branches, reflecting linguistic and cultural distinctions. Western Numic speakers, including Northern Paiute (also known as Paviotso, including Bannock dialects) and Mono, occupied the western Great Basin, extending from central-eastern California—particularly the Sierra Nevada foothills and areas around Mono Lake—northward into southern Oregon and western Nevada, such as the Harney and Surprise Valleys.[40] Central Numic territories centered on the Shoshone heartland across Wyoming, Idaho, Nevada, and Utah, with subgroups like the Western Shoshone in the Ruby Valley and Panamint Shoshone in the Death Valley region; the Comanche branch extended eastward from this core into the southern Great Plains, including parts of western Texas, Oklahoma, and New Mexico.[42][43] Southern Numic speakers, comprising Southern Paiute, Ute, Kawaiisu, and Chemehuevi, held lands in southern Utah, northern Arizona, western Colorado, and southern California; for instance, the Kawaiisu ranged across the Tehachapi Mountains and southern Sierra Nevada watersheds, while Southern Paiute groups like the Moapa and Kaibab inhabited areas around the Colorado River plateaus.[40][43][44] These territories were shaped by environmental adaptations to the Great Basin's arid basins, rugged mountains, and intermittent rivers, which dictated seasonal subsistence patterns centered on foraging and hunting. Numic groups, particularly Shoshone speakers, relied heavily on piñon pine zones in upland areas like the Saline and Panamint Valleys for nut harvesting, which supported communal gatherings and provided a staple food source during winters.[43][45] Numic territories abutted those of non-Numic groups, creating defined boundaries influenced by linguistic and cultural divides. To the west, Western Numic areas bordered Hokan-speaking Washoe lands around Lake Tahoe and the northern Sierra Nevada, while northern extensions of Northern Paiute territories approached Salishan-speaking groups in the Columbia Plateau fringes of Oregon and Idaho.[40][43]Modern Distribution and Speakers

The Numic languages are collectively spoken by an estimated 3,000 to 4,000 individuals as of 2025, with all speakers residing within the United States and ongoing declines attributed to assimilation pressures, intergenerational language shift, and urbanization.[46] For instance, Northern Paiute maintains around 500 fluent speakers, primarily in northern Nevada and southern Oregon, while Comanche has fewer than 50 fluent speakers, mostly in Oklahoma, and the Ute-Southern Paiute dialect cluster accounts for about 1,500 speakers across Utah, Colorado, and Arizona.[47][48][49] In contemporary settings, Numic speakers are concentrated on federal reservations and in adjacent urban areas, reflecting post-colonial relocations and land allotments. Key communities include the Pyramid Lake Paiute Reservation in Nevada for Northern Paiute speakers, the Uintah and Ouray Indian Reservation in Utah for Ute dialects, the Wind River Indian Reservation in Wyoming for Eastern Shoshoni, the Bishop Paiute Reservation in California for Mono (Owens Valley Paiute), and the Comanche Nation lands in southwestern Oklahoma extending into Texas.[50] Smaller pockets exist in California for Timbisha Shoshone near Death Valley and Kawaiisu descendants in the Tehachapi Mountains, though these are increasingly urbanized with speakers relocating to cities like Los Angeles and Reno. All Numic languages are classified as definitely endangered according to UNESCO's Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger.[51] Revitalization efforts include immersion programs, such as the Timbisha Language School on the Death Valley Indian Reservation, which integrates daily instruction for children, and digital apps developed by tribes like the Comanche Nation for vocabulary building. However, urban diaspora among younger generations hinders fluent transmission, with many speakers commuting between reservations and off-reservation employment. Demographic surveys reveal a predominance of elderly fluent speakers, with the majority over 60 years old and first-language (L1) acquisition now rare among those under 40, exacerbating generational gaps. Gender imbalances are also noted, with slightly more female speakers in some communities like Southern Ute, though overall participation in revitalization classes shows increasing youth involvement, particularly among women.Phonology

Proto-Numic Sound System

The reconstruction of the Proto-Numic sound system relies on the comparative method, examining sound correspondences and cognates across the three major branches of Numic—Western, Central, and Southern—to identify ancestral forms shared by all descendants. This method confirms features like original nasal consonants, as evidenced by denasalization processes in Western Numic languages, where proto-nasals appear as orals in certain environments, indicating their presence in the parent language.[52] Proto-Numic had a vowel inventory of five short vowels—/i/, /ɨ/, /u/, /a/, /o/—distinguished by a phonemic length contrast, such as /iː/ versus /i/. The system lacked diphthongs, maintaining a simple monophthongal structure. The consonant inventory comprised stops /p/, /t/, /k/, /ʔ/; the affricate /t͡s/; fricatives /s/, /x/; nasals /m/, /n/, /ŋ/; and approximants /w/, /j/. Three series were distinguished for obstruents—geminating, nasalizing, and spirantizing—adding complexity to stops and affricates in intervocalic contexts.[52] Phonotactics permitted open (CV) or closed (CVC) syllables, with no initial consonant clusters; word-initial position typically featured a single consonant followed by a vowel. Geminates, such as /pp/ or /tt/, were allowed in intervocalic positions, and nasal-stop clusters like /mp/ or /nt/ occurred medially. Primary stress fell on the first syllable, influencing vowel quality and contributing to the overall prosodic pattern.[52]Major Phonological Developments

The major phonological developments in Numic languages involve systematic sound changes from Proto-Numic that distinguish the three branches—Western, Central, and Southern—while reflecting a divergence period of approximately 1,000 to 1,500 years, correlating with archaeological evidence for expansion from a Great Basin homeland. These innovations primarily affect vowels and consonants, driven by prosodic factors like stress and vowel quality, and support the internal classification of Numic as a coherent subgroup of Uto-Aztecan.[53][25] Vowel shifts in Numic are relatively conservative but branch-specific. In Central Numic, the central vowel *ɨ, reconstructed for Proto-Numic with short and long variants, is preserved, and a new /e/ vowel developed, resulting in a six-vowel system (i, e, ɨ, a, o, u); Proto-Numic *o shifts to *a in certain environments, such as before velars or in unstressed syllables, contributing to a more open vocalic system in languages like Shoshoni.[25] The *ɨ is preserved in Central and Southern Numic but lost in Western Numic, where it merges with *i or reduces to a schwa-like vowel, leading to vowel reduction and simplification in languages like Northern Paiute.[25] These changes alter contrasts in Western varieties.[54] Consonant changes are more divergent across branches, often involving lenition, gemination, and aspiration. In Central Numic, Proto-Numic geminates (*pp, *tt, *kk) undergo a conditioned split based on stress: those following stressed vowels remain geminate (*pp > pp), while those after unstressed vowels develop preaspiration (*pp > hp), as seen in Shoshoni hibikkwa 'drinks' (from geminating) versus tikkahkwa 'eats' (from aspirating).[52] This preaspiration (e.g., hp, ht, hk) is a hallmark innovation, evolving further into fricatives in some dialects.[52] Western Numic features voicing of stops, alongside a nasal-stop cluster shift to voiced geminates (*mp > bb, *nt > nd), as in Mono forms reflecting broader lenition of fortis series.[55] In Southern Numic, preservation of geminates is common, but reanalysis occurs in Kawaiisu, where nasal-stop clusters like *nt yield nasals (*nt > nn), and affricates merge (*t͡s > s) in Ute dialects, reducing the obstruent inventory. Some Southern dialects, such as those east of Chemehuevi in Colorado River Numic, lost postvocalic *h.[7] These developments illustrate Numic's internal diversification, with shared innovations like the three Proto-Numic consonant series (spirantizing, geminating, nasalizing) undergoing branch-specific modifications.[12] For instance, Proto-Uto-Aztecan *paka 'bread' yields reflexes like paxa in Western Numic and paʔa in Central forms, highlighting consistent shifts in stops and vowels across the branch.[25]Grammar

Typological Characteristics

Numic languages exhibit agglutinative morphology characterized by a predominance of suffixing, where multiple affixes are added to roots to encode grammatical relations such as case, tense, aspect, and directionality.[56] This structure allows for complex word formation through sequential morpheme attachment, as seen in Shoshone verbs that combine roots with suffixes for progressive aspect (-wVnnV) and perfective (-hu).[56] Basic word order is typically subject-object-verb (SOV), though it displays flexibility influenced by discourse pragmatics, with occasional subject-verb inversion in questions or focused constructions.[56][57] These languages are head-marking, with verbs indexing arguments through affixes that agree in person, number, and sometimes gender, while dependents like nouns carry minimal marking beyond basic cases.[56] Polysynthesis occurs at a moderate level, featuring noun incorporation into verbs to form compound predicates (e.g., body-part incorporation in event descriptions) and serial verb constructions, but without the extensive noun incorporation or verb-complex elaboration typical of highly polysynthetic languages.[58] Clause linking employs postpositions for spatial and temporal relations, alongside switch-reference systems in many varieties that mark same-subject (-deN) versus different-subject (-gu) continuity via verbal suffixes.[59][56] Evidentiality is grammaticalized in several branches, particularly Southern Numic, through suffixes or particles indicating sensory evidence, reported hearsay (e.g., quotative gwa'i in Shoshone), or inferential sources.[60][56] Phonologically, Numic languages feature simple syllable structures, predominantly CV or CVC, with limited consonant clusters and no tones, distinguishing them from tonal Uto-Aztecan relatives like some Southern varieties.[56] Vowel harmony appears in select contexts, such as suffix assimilation to stem vowels in Central Numic dual markers or Southern Numic alternations, but it is not pervasive across the branch.[2] These traits reflect inheritance from Proto-Uto-Aztecan, including postpositional phrases and switch-reference for dependent clause coordination, adapted with Numic-specific innovations like enhanced suffixal complexity.[59][61]Nominal and Verbal Morphology

Numic languages feature agglutinative nominal morphology, with nouns typically requiring an absolutive suffix in their base form when unpossessed, such as *-pa(i) in Proto-Numic, which manifests as -pa, -pe, -pu, -tu, or -a across branches to indicate non-possessed status.[3] Case marking is realized through additional suffixes: the subjective case is generally unmarked (zero morpheme), the objective case uses forms like -i, -ha, or -na (as in Shoshone baa 'water' → bai 'water-OBJ'), and the possessive case is derived by adding a nasal element -n or -N to the objective form (e.g., Shoshone bai → baiN 'water-POSS').[56] Gender distinctions are absent throughout the family, a retention from Proto-Uto-Aztecan (PUA).[62] Number marking includes singular (unmarked), dual, and plural categories, inherited from PUA but with branch-specific developments; the dual, for instance, derives from innovations on the numeral 'two' (*waha in Proto-Central Numic), expanding beyond pronouns to nouns and verbs in Central Numic languages like Shoshone (dual subjective -neweH, e.g., waipe-neweH 'woman-DU.SUBJ') and Timbisha (-aŋku for dual subjective).[2] Plural is marked by suffixes like -neeN in Shoshone (e.g., waipe-neeN 'woman-PL.SUBJ/OBJ/POSS').[56] In Western Numic (e.g., Northern Paiute), dual marking is less pervasive, often limited to pronouns, while Central Numic shows the most elaborate system across syntactic categories.[4] Verbal morphology is prefixing and suffixing, with pronominal prefixes marking subject person (e.g., 1sg nɨ- in Northern Paiute and related forms like ne- in Shoshone) and instrumental/directional prefixes indicating manner or motion, such as pi- 'with the back/behind' or 'go' in Numic verbs (e.g., pi-kwai 'go-OBJ' in directional contexts).[63] Suffixes encode tense-aspect-mood (TAM), with common forms including present -yu (Shoshone mia'yu 'is coming'), past -pe/-zi (e.g., Northern Paiute nɨ-ttɨ-zi '1SG-see-PFV' 'I saw it'), and durative/habitual -na/-mi (Shoshone reka-na 'eat-DUR'; Ute -mi for habitual, e.g., 'eat-HAB').[56] Southern Numic languages like Ute exhibit more complex aspect systems, incorporating habitual -mi alongside progressive and completive distinctions.[64] Switch-reference is marked by verbal suffixes, a PUA retention with Numic elaboration: same-subject forms like -deN/-tɨ (Shoshone nuki-noon-deN 'run-SS' 'while running [same subject]'), and different-subject -gu/-ga (e.g., Shoshone -gu 'DS').[56] Evidential nuances represent Numic innovations, with suffixes like -kai in Southern Paiute indicating visual evidence (e.g., on verbs for 'seen' events), extending PUA sensory distinctions.[12] Overall, core patterns trace to PUA prefixing for person and suffixing for TAM/switch-reference, but Numic branches innovate in directional complexity and evidential specificity.[62]Lexicon and Comparative Studies

Shared Vocabulary

The Numic languages demonstrate significant retention of core vocabulary, with lexicostatistical analyses indicating cognacy rates of approximately 68-85% across branches for basic lexical items drawn from comparative lists of around 300 terms. This high degree of shared lexicon is particularly evident in Swadesh-style basic vocabulary, where 204 cognate sets are common to all three major branches (Western, Central, and Southern Numic), supporting their close genetic relationship within the Uto-Aztecan family. For instance, body part terms show strong continuity, such as Proto-Numic *pu(i) 'eye', reflected in Northern Paiute pui or puʔipi, Shoshone pui, and Southern Paiute puʔi; *akoN 'tongue', appearing as Mono éġo and Comanche eko; and *naka 'ear', seen in widespread forms like naka- across Numic varieties.[3][65][66][66] Kinship and numeral terms further illustrate this retention, with Proto-Numic *kuma 'husband' preserved in Northern Paiute kuma and Southern Paiute kummá, and numbers like *winna 'one' (with reflexes in Shoshone winnɨ) and *waha 'two' (Central Numic) showing consistent forms across branches. Environmental adaptations are prominent in semantic fields related to the Great Basin and Colorado Plateau habitats, including shared terms for desert flora such as *tīpat 'pinyon pine', uniform among Northern Uto-Aztecan languages including Numic, reflecting proto-homelands in pinyon-juniper zones. Hunting and gathering lexicon, like *tɨhɨɲya 'deer' (Northern Paiute tɨhɨdda, Mono tɨhɨya), also exhibits high cognacy, underscoring adaptations to arid ecosystems.[7][67][12][2] Post-contact innovations introduced shared vocabulary for new cultural elements, notably horse-related terms borrowed from Spanish via initial contact with Puebloan groups. The term *puŋku 'horse' (Northern Paiute puggu, Shoshone puŋku, Comanche puuku) derives from Spanish caballo, adapted phonologically across branches and diffusing rapidly after the 16th-century introduction of horses, transforming Numic mobility and warfare. Internal borrowings are minimal due to the family's recency (ca. 1000-1500 years), but external influences from Spanish and English are evident in terms like *kabayo variants for horse-related items. Shared innovations, such as potential reflexes of /*tampi/ 'sun' across branches, further highlight post-proto developments, though these are less uniform than core retentions. Lexicostatistical comparisons using modified Swadesh lists confirm the closest lexical ties within Central Numic (e.g., Shoshone-Bannock and Timbisha-Panamint at ~85% cognates), decreasing to ~70% with Western and Southern branches.[12][10][3][68]Sample Cognates

The section on sample cognates illustrates the genetic relationships among Numic languages through selected vocabulary items reconstructed to Proto-Numic or Proto-Uto-Aztecan (with Numic reflexes), demonstrating shared inheritance and branch-specific innovations such as vowel lengthening in Western Numic, preaspiration in Central Numic, and spirantization in Southern Numic. These examples cover nouns, verbs, and numerals, drawn from comparative reconstructions that highlight systematic sound correspondences across the Western (e.g., Mono, Northern Paiute), Central (e.g., Shoshoni, Timbisha), and Southern (e.g., Ute, Kawaiisu) branches.[69][2][52][66] The following table presents 12 representative cognate sets, with Proto-Numic forms where reconstructible and reflexes in daughter languages (transcriptions follow source orthographies; G = geminate, H = aspirate, N = nasalizer series from Proto-Numic consonant distinctions). These sets exemplify innovations like the development of preaspiration (*p > ph in Central Numic for some items) and vowel shifts (*ɨ > u in some Southern forms).[69][52]| English | Proto-Numic/Proto-Uto-Aztecan | Western Numic (Mono) | Western Numic (Northern Paiute) | Central Numic (Shoshoni/Timbisha) | Southern Numic (Ute/Kawaiisu) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person | *nɨmɨ | nim | numu | num / nümü | nuu / nümü |

| Eye | *puʔi(h) | púsi’ | puʔipi | pui / pui | puʔi / puʔi |

| Bone | *tˢuhni | tˢuhmippɯh | tˢuhni | tˢuhmippɯh / tˢuhni | tˢuhni / tˢuhni |

| Water | *pa | pa- | pa- | paa / pa- | pa / pa- |

| Drink (v.) | *hipi | hipi- | hipi- | hipi / hipi G | hipi- / hipi- |

| Cook/Ripe (v.) | *kʷasɯ | kosi- | kwasi- | kʷasɯ / kʷasɯ | kʷaʃɯī / kʷasɯ- |

| Arm | *pɯ(h)ta | pɯ̱tta | pɯtta | pɯtapɯ / pɯta | pɯta / pɯtapɯ |

| Bow (n.) | *etɯ | e̱tɯ̄ | etɯ | etɯn / etɯn | atᶴɯ / ātᶴi |

| Eagle (n.) | *kʷi(ʔ)nā(ʔa) | kʷiʔnāʔ | kʷiʔnā | kʷinā / kʷina | kʷaná-ci / kwana-zi |

| Cloud (n.) | *tō̆(h) | tōppe | tōppɯh | tonnoppɯh / tohoppɯ | tohoppɯ / tohoppɯ |

| Coyote (n.) | *isa / *itˢa | isaʔ | issa | itˢappɯ / itˢa | isakawɯ / isa |

| Five (num.) | *namɯki(h) | manikiī | manniki- | maniki / maniki | maniki / maniki |