Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

OTS 44

View on Wikipedia

| Observation data Epoch J2000.0 Equinox J2000.0 | |

|---|---|

| Constellation | Chamaeleon |

| Right ascension | 11h 10m 11.5s |

| Declination | −76° 32′ 13″ |

| Characteristics | |

| Spectral type | M9.5±1.0[1][2] |

| Astrometry | |

| Distance | 522–544 or 626 ly (160–170 or 192 pc)[3][4] |

| Details | |

| Mass | 6–17 MJ, average 11.5[3] MJup |

| Radius | 3.2 or 3.6[2] RJup |

| Luminosity | 0.00126±0.00023[a] – 0.0024[3] L☉ |

| Temperature | 1700±100[2][3] K |

| Age | 1–6[2] Myr |

| Other designations | |

| 2MASS J11100934–7632178, CHSM 16658,[5] SSTgbs J1110093–763218,[5] TIC 454329342, [GMM2009] Cha I 27[5] | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | data |

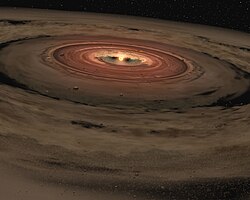

OTS 44 is a young, free-floating planetary-mass brown dwarf or rogue planet, located 520 to 630 light-years (160 to 192 parsecs) away in the star-forming molecular cloud Chamaeleon I in the constellation Chamaeleon. It is surrounded by a circumstellar disk of gas and dust, from which it is actively accreting mass at an approximate rate of 500 billion kilograms per second (or equivalently, 7.6×10−12 solar masses per year).[3] With an estimated age between 1 and 6 million years, OTS 44 has not existed long enough to cool down, so it glows red with a temperature of around 1,700 K (1,430 °C; 2,600 °F) and a stellar spectral type of M9.5.[2] It likely formed from the gravitational collapse of gas and dust, a similar process to how stars typically form.[6]

The disk of OTS 44 is estimated to span at least several astronomical units in radius with a flared shape—decreasing in density but increasing in vertical thickness at farther distances from the object.[3]: 2–3 OTS 44's disk contains a total estimated mass of approximately 0.1 Jupiter masses or 30 Earth masses,[3] with a small fraction of this mass constituting dust in the disk.[7][8] OTS 44's disk will eventually coalesce to form a planetary system.[9][10]

Discovery

[edit]OTS 44 was discovered in images taken on 1–3 March 1996 by Japanese astronomers Yumiko Oasa, Motohide Tamura, and Koji Sugitani, during a search for young stellar objects and brown dwarfs in the core of the Chamaeleon I molecular cloud.[11]: 338 The discovery images were taken with the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory's 1.5-metre (4.9 ft) telescope in Chile, which was equipped with the J, H, and K filters to measure the near-infrared colors of these objects.[12]: 1095 [11]: 338–339 The discoverers found 61 near-infrared-emitting objects and included them in their own catalogue,[11]: 339 which became known as the Oasa–Tamura–Sugitani (OTS) catalogue.[13][1]: 565

OTS 44 was the 44th object and one of the dimmest objects listed in the OTS catalogue.[11]: 337 [1]: 565 The discoverers identified OTS 44 as a brown dwarf candidate because it appeared much dimmer and redder than other young stars in Chameleon I, which meant that it should have a very low mass if it shared the same age as these stars.[12]: 1046 [11]: 341 The discoverers published their analysis and identification of OTS 44 as a brown dwarf candidate in the journal Science in November 1998.[12]

In November 2004, Kevin L. Luhman, Dawn E. Peterson, and S. Thomas Megeath announced the confirmation of OTS 44 as a low-mass brown dwarf.[14] Using spectroscopic observations by the Gemini South telescope from March 2004, the researchers determined that OTS 44's mass lay close to the ~0.012 solar mass (13 Jupiter mass) boundary between giant planets and brown dwarfs, which made OTS 44 one of the least massive free-floating brown dwarfs confirmed at the time.[1][15]: L53

Location and age

[edit]

OTS 44 is located in the constellation Chamaeleon at a declination of approximately 76.5° south of the celestial equator.[5] It is situated within the core of Chamaeleon I, one of the three major star-forming molecular clouds of the Chamaeleon complex.[12][11] Chamaeleon I is one of the nearest star-forming regions to the Sun,[11]: 336 at an estimated distance of either 160–170 parsecs (520–550 light-years) (according to 1999 parallax measurements by the Hipparcos satellite[16]: 580 [1]: 565 ) or 192 pc (630 ly) (according to 2018 parallax measurements by the Gaia satellite[4]: 565 ). Astronomers assume that OTS 44 lies at the same distance as Chamaeleon I.[7]: 2 [4]: 565

As a member of Chamaeleon I, OTS 44 is inferred to share the same age as other young stellar objects in the region, which are known to be between 1 and 6 million years old.[2]: 13, 19 At this age, substellar objects like OTS 44 are hot and luminous.[2]: 1–2 Observations of active accretion around OTS 44 indicate that it formed in a similar process to how stars form—via direct gravitational collapse of concentrated gas and dust.[6]: 1019–1020 OTS 44 will gradually cool and contract over time—becoming an L-type brown dwarf at about 10 million years of age, and then a Y dwarf after 1 billion years of age.[6]: 1024

Physical characteristics

[edit]

2O vapor) in its atmosphere. The spectrum of the M8-type brown dwarf CHSM 17173 (red) is shown for comparison.[1]

The near-infrared spectrum of OTS 44 exhibits deep absorption bands caused by steam (water vapor) in its atmosphere, indicating a relatively cool temperature corresponding to a late spectral type of M9.5±1.0.[1] Additional substances including elemental sodium (Na), potassium (K), iron hydride (FeH), and carbon monoxide (CO) have been spectroscopically detected in OTS 44's atmosphere.[2]: 4, 7, 10 OTS 44 is estimated to have an effective temperature of 1,700 ± 100 K (1,427 ± 100 °C; 2,600 ± 180 °F), based on spectral energy distribution modeling with the object's atmospheric dust taken into account.[3]: 2 [2]: 17 OTS 44 stands out from cool main-sequence stars and red giants because it is much redder and brighter in near-infrared.[11]: 339–340 Extinction by foreground dust has been observed to cause additional reddening in OTS 44's near-infrared colors (0.3±0.3-magnitude dimming in J-band),[1]: 567 but not in its optical colors.[2]: 3

OTS 44 is a dim object with a luminosity between 0.001 and 0.002 times that of the Sun.[3]: 2 [a] As a young and hot object, OTS 44 is expected to have a radius larger than that of Jupiter.[2]: 1, 19, 23 A Stefan–Boltzmann law calculation using OTS 44's luminosity and temperature suggests a "semi-empirical" radius of 3.5+0.6

−0.5 RJ, whereas a spectral energy distribution fit with OTS 44's disk taken into account suggests a radius between 3.2 and 3.6 RJ.[2]: 15, 17, 19 OTS 44 is estimated to be 6–17 times more massive than Jupiter,[7] though it is more likely below 13 Jupiter masses—in the planetary mass range, where it cannot fuse deuterium unlike brown dwarfs.[2] Hence, astronomers have also categorized OTS 44 as a free-floating planet.[6][7]

Circumstellar disk

[edit]

In February 2005, a team of astronomers led by Kevin Luhman announced the discovery of a circumstellar disk around OTS 44.[10][9] Their discovery was based on the Spitzer Space Telescope's detection of excess mid-infrared thermal emission from OTS 44, which indicated the presence of warm dust surrounding the object.[15] As one of the least massive free-floating objects known at the time, OTS 44 claimed the record for the least massive object known to have a circumstellar disk and demonstrated that such disks could exist around planetary-mass objects.[15]

Estimates based on OTS 44's spectral energy distribution (SED) suggests that its disk contains a total mass of about 30 Earth masses.[3] Observations with the SINFONI spectrograph at the Very Large Telescope show that OTS 44 is accreting matter from its disk at the rate of approximately 10−11 of the mass of the Sun per year.[3] It could eventually develop into a planetary system.[17]

Observations with ALMA detected OTS 44's disk in millimeter wavelengths. The observations constrained the dust mass of the disk between 0.07 and 0.63 M🜨, but these mass estimates are limited by assumptions on poorly constrained parameters.[7] Another work estimates the dust mass to 0.064 M🜨 (5.2 M☾) for dust particles of 1 mm in size and 0.295 M🜨 (24 M☾) for dust particles of 1 μm in size.[4]

See also

[edit]Other free-floating rogue planets and brown dwarfs with protoplanetary disks:

- Cha 110913-773444, rogue planet or brown dwarf surrounded by what appears to be a dusty disk

- Cha 1107−7626, a young rogue planet that underwent an episode of rapid accretion of material from its disk

- 2MASS J11151597+1937266, a young rogue planet or brown dwarf actively accreting material from its disk

- KPNO-Tau 12, another young rogue planet or brown dwarf that is actively accreting material from its disk

- J1407b, a possible disked object thought to have transited the star V1400 Centauri

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b In Table of 8 of Bonnefoy et al. (2014), OTS 44's effective luminosity is given as a base 10 logarithm: −2.90±0.08. The luminosity of 0.00126±0.00023 L☉ can be obtained by taking 10 to the power of the aforementioned logarithm value; the uncertainty is calculated via propagation of error.[2]: 19

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Luhmann, K. L.; Peterson, D. E.; Megeath, S. T. (2004). "Spectroscopic Confirmation of the Least Massive Known Brown Dwarf in Chamaeleon". The Astrophysical Journal. 617 (1): 565–568. arXiv:astro-ph/0411445. Bibcode:2004ApJ...617..565L. doi:10.1086/425228. S2CID 18157277.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Bonnefoy, M.; Chauvin, G.; Lagrange, A.-M.; Rojo, P.; Allard, F.; Pinte, C.; Dumas, C.; Homeier, D. (2014). "A library of near-infrared integral field spectra of young M-L dwarfs". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 562 (127): A127. arXiv:1306.3709. Bibcode:2014A&A...562A.127B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201118270. S2CID 53064211.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Joergens, V.; Bonnefoy, M.; Liu, Y.; Bayo, A.; Wolf, S.; Chauvin, G.; Rojo, P. (1 October 2013). "OTS 44: Disk and accretion at the planetary border". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 558: L7. arXiv:1310.1936. Bibcode:2013A&A...558L...7J. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201322432. ISSN 0004-6361.

- ^ a b c d Wu, Ya-Lin; Bowler, Brendan P.; Sheehan, Patrick D.; Close, Laird M.; Eisner, Joshua A.; Best, William M. J.; Ward-Duong, Kimberly; Zhu, Zhaohuan; Kraus, Adam L. (1 May 2022). "ALMA Discovery of a Disk around the Planetary-mass Companion SR 12 c". The Astrophysical Journal. 930 (1): L3. arXiv:2204.06013. Bibcode:2022ApJ...930L...3W. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ac6420. ISSN 0004-637X.

- ^ a b c d "OTS 44". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 23 December 2025.

- ^ a b c d Joergens, V.; Bonnefoy, M.; Liu, Y.; Bayo, A.; Wolf, S. (January 2015). The Coolest 'Stars' are Free-Floating Planets (PDF). 18th Cambridge Workshop on Cool Stars, Stellar Systems, and the Sun. Vol. 18. Lowell Observatory. pp. 1019–1026. arXiv:1407.7864. Bibcode:2015csss...18.1019J.

- ^ a b c d e Bayo, Amelia; Joergens, Viki; Liu, Yao; Brauer, Robert; Olofsson, Johan; Arancibia, Javier; et al. (May 2017). "First Millimeter Detection of the Disk around a Young, Isolated, Planetary-mass Object". Astrophysical Journal Letters. 841 (1): L11. arXiv:1705.06378. Bibcode:2017ApJ...841L..11B. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/aa7046. hdl:10150/624481. ISSN 0004-637X. S2CID 73605838.

- ^ Bayo, Amelia; Joergens, Viki; Liu, Yao; Brauer, Robert; Olofsson, Johan; Arancibia, Javier; et al. (May–June 2018). Modeling of the Disk around a Young, Isolated, Planetary-mass Object (PDF). Frontier Research in Astrophysics - III. Mondello (Palermo), Italy. Bibcode:2019frap.confE..70B. doi:10.22323/1.331.0070.

- ^ a b "Tiny Brown Dwarf's Disk May Form Miniature Solar System". Center for Astrophysics. Harvard University. 7 February 2005. Retrieved 7 December 2025.

- ^ a b "Astronomers Discover Beginnings of 'Mini' Solar System". Spitzer Space Telescope. Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 7 February 2005. Retrieved 7 December 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Oasa, Yumiko; Tamura, Motohide; Sugitani, Koji (November 1999). "A Deep Near-Infrared Survey of the Chamaeleon I Dark Cloud Core". The Astrophysical Journal. 526 (1): 336–343. Bibcode:1999ApJ...526..336O. doi:10.1086/307964. S2CID 120597899.

- ^ a b c d Tamura, Motohide; Itoh, Yoichi; Oasa, Yurniko; Nakajima, Tadashi (November 1998). "Isolated and Companion Young Brown Dwarfs in the Taurus and Chamaeleon Molecular Clouds". Science. 282 (5391): 1095–1097. Bibcode:1998Sci...282.1095T. doi:10.1126/science.282.5391.1095. PMID 9804541. S2CID 46703803.

- ^ "Dictionary of Nomenclature of Celestial Objects". SIMBAD. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. 19 December 2025. Archived from the original on 23 December 2025.

- ^ "Strong spectral signatures of steam betray low mass brown dwarf using GNIRS at Gemini South". NOIRLab. 30 November 2004. Retrieved 23 December 2025.

- ^ a b c Luhman, K. L.; et al. (February 2005), "Spitzer Identification of the Least Massive Known Brown Dwarf with a Circumstellar Disk", The Astrophysical Journal, 620 (1): L51–L54, arXiv:astro-ph/0502100, Bibcode:2005ApJ...620L..51L, doi:10.1086/428613, S2CID 15340083

- ^ Bertout, C.; Robichon, N.; Arenou, F. (December 1999). "Revisiting Hipparcos data for pre-main sequence stars". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 352: 574–586. arXiv:astro-ph/9909438. Bibcode:1999A&A...352..574B.

- ^ "Blurring the lines between stars and planets: Lonely planets offer clues to star formation". Max Planck Institute for Astronomy. 9 October 2013. Archived from the original on 10 October 2013. Retrieved 1 September 2014.