Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Planetary system

View on Wikipedia

A planetary system consists of a set of non-stellar bodies which are gravitationally bound to and in orbit of a star or star system. Generally speaking, such systems will include planets, and may include other objects such as dwarf planets, asteroids, natural satellites, meteoroids, comets, planetesimals[1][2], and circumstellar disks. The Solar System is an example of a planetary system, in which Earth, seven other planets, and other celestial objects are bound to and revolve around the Sun.[3][4] The term exoplanetary system is sometimes used in reference to planetary systems other than the Solar System. By convention planetary systems are named after their host, or parent, star, as is the case with the Solar System being named after "Sol" (Latin for sun).

As of 29 July 2025, there are 6,032 confirmed exoplanets in 4,530 planetary systems, with 989 systems having more than one planet.[5] Debris disks are known to be common while other objects are more difficult to observe.

Of particular interest to astrobiology is the habitable zone of planetary systems where planets could have surface liquid water, and thus, the capacity to support Earth-like life.

Definition

[edit]The International Astronomical Union (IAU) has described a planetary system as the system of planets orbiting one or more stars, brown dwarfs or stellar remnants. The IAU and NASA consider the Solar System a planetary system, including its star the Sun, its planets, and all other bodies orbiting the Sun.[6][7]

Other definitions of planetary system explicitly include all bodies gravitationally bound to one or more stars.[8]

History

[edit]Heliocentrism

[edit]Heliocentrism is a planetary model that places the Sun is at the center of the universe, as opposed to geocentrism (placing Earth at the center of the universe).

The idea was first proposed in Western philosophy and Greek astronomy as early as the 3rd century BC by Aristarchus of Samos,[9] but received no support from most other ancient astronomers.

Some also interpret Aryabhatta's writings in Āryabhaṭīya as implicitly heliocentric, although this has also been rebutted.[10]

Discovery of the Solar System

[edit]

De revolutionibus orbium coelestium by Nicolaus Copernicus, published in 1543, presented the first mathematically predictive heliocentric model of a planetary system. 17th-century successors Galileo Galilei, Johannes Kepler, and Sir Isaac Newton developed an understanding of physics which led to the gradual acceptance of the idea that the Earth moves around the Sun and that the planets are governed by the same physical laws that governed Earth.

Speculation on extrasolar planetary systems

[edit]In the 16th century the Italian philosopher Giordano Bruno, an early supporter of the Copernican theory that Earth and other planets orbit the Sun, put forward the view that the fixed stars are similar to the Sun and are likewise accompanied by planets. He was burned at the stake for his ideas by the Roman Inquisition.[11]

In the 18th century, the same possibility was mentioned by Sir Isaac Newton in the "General Scholium" that concludes his Principia. Making a comparison to the Sun's planets, he wrote "And if the fixed stars are the centres of similar systems, they will all be constructed according to a similar design and subject to the dominion of One."[12]

His theories gained popularity through the 19th and 20th centuries despite a lack of supporting evidence. Long before their confirmation by astronomers, conjecture on the nature of planetary systems had been a focus of the search for extraterrestrial intelligence and has been a prevalent theme in fiction, particularly science fiction.

Detection of exoplanets

[edit]The first confirmed detection of an exoplanet was in 1992, with the discovery of several terrestrial-mass planets orbiting the pulsar PSR B1257+12. The first confirmed detection of exoplanets of a main-sequence star was made in 1995, when a giant planet, 51 Pegasi b, was found in a four-day orbit around the nearby G-type star 51 Pegasi. The frequency of detections has increased since then, particularly through advancements in methods of detecting extrasolar planets and dedicated planet-finding programs such as the Kepler mission.

Origin and evolution

[edit]

Planetary systems come from protoplanetary disks that form around stars as part of the process of star formation.

During formation of a system, much material is gravitationally-scattered into distant orbits, and some planets are ejected completely from the system, becoming rogue planets.

Evolved systems

[edit]High-mass stars

[edit]Planets orbiting pulsars have been discovered. Pulsars are the remnants of the supernova explosions of high-mass stars, but a planetary system that existed before the supernova would likely be mostly destroyed. Planets would either evaporate, be pushed off of their orbits by the masses of gas from the exploding star, or the sudden loss of most of the mass of the central star would see them escape the gravitational hold of the star, or in some cases the supernova would kick the pulsar itself out of the system at high velocity so any planets that had survived the explosion would be left behind as free-floating objects. Planets found around pulsars may have formed as a result of pre-existing stellar companions that were almost entirely evaporated by the supernova blast, leaving behind planet-sized bodies. Alternatively, planets may form in an accretion disk of fallback matter surrounding a pulsar.[13] Fallback disks of matter that failed to escape orbit during a supernova may also form planets around black holes.[14]

Lower-mass stars

[edit]Many low-mass stars are expected to have rocky planets, with their planetary systems primarily consisting of rock- and ice-based bodies. This is because low-mass stars have less material in their planetary disks, making it unlikely that the planetesimals within will reach the critical mass necessary to form gas giants. The planetary systems of low-mass stars also tend to be compact, as such stars tend to have lower temperatures, resulting in the formation of protoplanets closer to the star.[15]

As stars evolve and turn into red giants, asymptotic giant branch stars, and eventually planetary nebulae, they engulf the inner planets, evaporating or partially evaporating them depending on how massive they are.[17][18] As the star loses mass, planets that are not engulfed move further out from the star.

If an evolved star is in a binary or multiple system, then the mass it loses can transfer to another star, forming new protoplanetary disks and second- and third-generation planets which may differ in composition from the original planets, which may also be affected by the mass transfer.

System architectures

[edit]The Solar System consists of an inner region of small rocky planets and outer region of large giant planets. However, other planetary systems can have quite different architectures. Studies suggest that architectures of planetary systems are dependent on the conditions of their initial formation.[19] Many systems with a hot Jupiter gas giant very close to the star have been found. Theories such as planetary migration or scattering have been proposed for the formation of large planets close to their parent stars.[20] At present,[when?] few systems have been found to be analogous to the Solar System with small terrestrial planets in the inner region, as well as a gas giant with a relatively circular orbit, which suggests that this configuration is uncommon.[21] More commonly, systems consisting of multiple Super-Earths have been detected.[22][23] These super-Earths are usually very close to their star, with orbits smaller than that of Mercury.[24]

Classification

[edit]Planetary system architectures may be partitioned into four classes based on how the mass of the planets is distributed around the host star:[25][26]

- Similar: The masses of all planets in a system are similar to each other. This architecture class is the most commonly-observed in our galaxy. Examples include TRAPPIST-1. The planets in these systems are said to be like 'peas in a pod'.[27]

- Mixed: The masses of planets in a system show large increasing or decreasing variations. Examples of such systems are Gliese 876 and Kepler-89.

- Anti-Ordered: The massive planets of a system are close to the star and smaller planets are further away from the star. There are currently no known examples of this architecture class.

- Ordered: The mass of the planets in a system tends to increase with increasing distance from the host star. The Solar System, with small rocky planets in the inner part and giant planets in the outer part, is a type of Ordered system.

Peas in a pod

[edit]Multiplanetary systems tend to be in a "peas in a pod" configuration meaning they tend to have the following factors:[27]

- Size: planets within a system tend to be either similar or ordered in size.

- Mass: planets within a system tend to be either similar or ordered in mass.

- Spacing: planets within a system tend to be equally spaced apart.

- Packing: small planets tend to be closely packed together, while large planets tend to have larger spacing.

Components

[edit]Planets and stars

[edit]

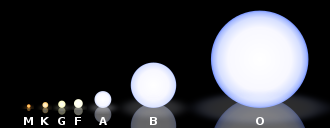

Most known exoplanets orbit stars roughly similar to the Sun: that is, main-sequence stars of spectral categories F, G, or K. One reason is that planet-search programs have tended to concentrate on such stars. In addition, statistical analyses indicate that lower-mass stars (red dwarfs, of spectral category M) are less likely to have planets massive enough to be detected by the radial-velocity method.[28][29] Nevertheless, several tens of planets around red dwarfs have been discovered by the Kepler space telescope by the transit method, which can detect smaller planets.

Exoplanetary systems may also feature planets extremely different from those in the Solar System, such as Hot Jupiters, Hot Neptunes, and Super-Earths.[30] Hot Jupiters and Hot Neptunes are gas giants, like their namesakes, but orbit close to their stars and have orbital periods on the order of a few days.[31] Super-Earths are planets that have a mass between that of Earth and planets like Neptune and Uranus, and can be made of rock and gas. There is a lot of variety among Super-Earths, with planets ranging from water worlds to mini-Neptunes.[32]

Circumstellar disks and dust structures

[edit]

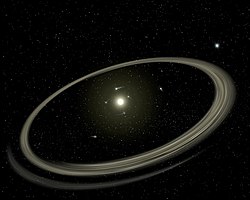

After planets, circumstellar disks are one of the most commonly-observed properties of planetary systems, particularly of young stars. The Solar System possesses at least four major circumstellar disks (the asteroid belt, Kuiper belt, scattered disc, and Oort cloud) and clearly-observable disks have been detected around nearby solar analogs including Epsilon Eridani and Tau Ceti. Based on observations of numerous similar disks, they are assumed to be quite common attributes of stars on the main sequence.

Interplanetary dust clouds have been studied in the Solar System and analogs are believed to be present in other planetary systems. Exozodiacal dust, an exoplanetary analog of zodiacal dust, the 1–100 micrometre-sized grains of amorphous carbon and silicate dust that fill the plane of the Solar System[33] has been detected around the 51 Ophiuchi, Fomalhaut,[34][35] Tau Ceti,[35][36] and Vega systems.

Comets

[edit]As of November 2014[update] there are 5,253 known Solar System comets[37] and they are thought to be common components of planetary systems. The first exocomets were detected in 1987[38][39] around Beta Pictoris, a very young A-type main-sequence star. There are now a total of 11 stars around which the presence of exocomets have been observed or suspected.[40][41][42][43] All discovered exocometary systems (Beta Pictoris, HR 10,[40] 51 Ophiuchi, HR 2174,[41] 49 Ceti, 5 Vulpeculae, 2 Andromedae, HD 21620, HD 42111, HD 110411,[42][44] and more recently HD 172555[43]) are around very young A-type stars.

Other components

[edit]Computer modelling of an impact in 2013 detected around the star NGC 2547-ID8 by the Spitzer Space Telescope, and confirmed by ground observations, suggests the involvement of large asteroids or protoplanets similar to the events believed to have led to the formation of terrestrial planets like the Earth.[45]

Based on observations of the Solar System's large collection of natural satellites, they are believed common components of planetary systems; however, the existence of exomoons has not yet been confirmed. The star 1SWASP J140747.93-394542.6, in the constellation Centaurus, is a strong candidate for a natural satellite.[46] Indications suggest that the confirmed extrasolar planet WASP-12b also has at least one satellite.[47]

Orbital configurations

[edit]Unlike the Solar System, which has orbits that are nearly circular, many of the known planetary systems display much higher orbital eccentricity.[48] An example of such a system is 16 Cygni.

Mutual inclination

[edit]The mutual inclination between two planets is the angle between their orbital planes. Many compact systems with multiple close-in planets interior to the equivalent orbit of Venus are expected to have very low mutual inclinations, so the system (at least the close-in part) would be even flatter than the Solar System. Captured planets could be captured into any arbitrary angle to the rest of the system. As of 2016[update] there are only a few systems where mutual inclinations have actually been measured[49] One example is the Upsilon Andromedae system: the planets c and d have a mutual inclination of about 30 degrees.[50][51]

Orbital dynamics

[edit]Planetary systems can be categorized according to their orbital dynamics as resonant, non-resonant-interacting, hierarchical, or some combination of these. In resonant systems the orbital periods of the planets are in integer ratios. The Kepler-223 system contains four planets in an 8:6:4:3 orbital resonance.[52] Giant planets are found in mean-motion resonances more often than smaller planets.[53] In interacting systems the planets' orbits are close enough together that they perturb the orbital parameters. The Solar System could be described as weakly interacting. In strongly interacting systems Kepler's laws do not hold.[54] In hierarchical systems the planets are arranged so that the system can be gravitationally considered as a nested system of two-bodies, e.g. in a star with a close-in hot Jupiter with another gas giant much further out, the star and hot Jupiter form a pair that appears as a single object to another planet that is far enough out.

Other, as yet unobserved, orbital possibilities include: double planets; various co-orbital planets such as quasi-satellites, trojans and exchange orbits; and interlocking orbits maintained by precessing orbital planes.[55]

Number of planets, relative parameters and spacings

[edit]

- On The Relative Sizes of Planets Within Kepler Multiple Candidate Systems, David R. Ciardi et al. December 9, 2012

- The Kepler Dichotomy among the M Dwarfs: Half of Systems Contain Five or More Coplanar Planets, Sarah Ballard, John Asher Johnson, October 15, 2014

- Exoplanet Predictions Based on the Generalised Titius-Bode Relation, Timothy Bovaird, Charles H. Lineweaver, August 1, 2013

- The Solar System and the Exoplanet Orbital Eccentricity - Multiplicity Relation, Mary Anne Limbach, Edwin L. Turner, April 9, 2014

- The period ratio distribution of Kepler's candidate multiplanet systems, Jason H. Steffen, Jason A. Hwang, September 11, 2014

- Are Planetary Systems Filled to Capacity? A Study Based on Kepler Results, Julia Fang, Jean-Luc Margot, February 28, 2013

Planet capture

[edit]Free-floating planets in open clusters have similar velocities to the stars and so can be recaptured. They are typically captured into wide orbits between 100 and 105 AU. The capture efficiency decreases with increasing cluster size, and for a given cluster size it increases with the host/primary[clarification needed] mass. It is almost independent of the planetary mass. Single and multiple planets could be captured into arbitrary unaligned orbits, non-coplanar with each other or with the stellar host spin, or pre-existing planetary system. Some planet–host metallicity correlation may still exist due to the common origin of the stars from the same cluster. Planets would be unlikely to be captured around neutron stars because these are likely to be ejected from the cluster by a pulsar kick when they form. Planets could even be captured around other planets to form free-floating planet binaries. After the cluster has dispersed some of the captured planets with orbits larger than 106 AU would be slowly disrupted by the galactic tide and likely become free-floating again through encounters with other field stars or giant molecular clouds.[56]

Zones

[edit]Habitable zone

[edit]

The habitable zone around a star is the region where the temperature range allows for liquid water to exist on a planet; that is, not too close to the star for the water to evaporate and not too far away from the star for the water to freeze. The heat produced by stars varies depending on the size and age of the star; this means the habitable zone will also vary accordingly. Also, the atmospheric conditions on the planet influence the planet's ability to retain heat so that the location of the habitable zone is also specific to each type of planet.

Habitable zones have usually been defined in terms of surface temperature; however, over half of Earth's biomass is from subsurface microbes,[57] and temperature increases as depth underground increases, so the subsurface can be conducive for life when the surface is frozen; if this is considered, the habitable zone extends much further from the star.[58]

Studies in 2013 indicate that an estimated 22±8% of Sun-like[a] stars have an Earth-sized[b] planet in the habitable[c] zone.[59][60]

Venus zone

[edit]The Venus zone is the region around a star where a terrestrial planet would have runaway greenhouse conditions like Venus, but not so near the star that the atmosphere completely escapes. As with the habitable zone, the location of the Venus zone depends on several factors, including the type of star and properties of the planets such as mass, rotation rate, and atmospheric clouds. Studies of the Kepler spacecraft data indicate that 32% of red dwarfs have potentially Venus-like planets based on planet size and distance from star, increasing to 45% for K-type and G-type stars.[d] Several candidates have been identified, but spectroscopic follow-up studies of their atmospheres are required to determine whether they are like Venus.[61][62]

Galactic distribution of planets

[edit]

The Milky Way is 100,000 light-years across, but 90% of planets with known distances are within about 2000 light years of Earth, as of July 2014. One method that can detect planets much further away is microlensing. The upcoming Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope could use microlensing to measure the relative frequency of planets in the galactic bulge versus the galactic disk.[63] So far, the indications are that planets are more common in the disk than the bulge.[64] Estimates of the distance of microlensing events is difficult: the first planet considered with high probability of being in the bulge is MOA-2011-BLG-293Lb at a distance of 7.7 kiloparsecs (about 25,000 light years).[65]

Population I, or metal-rich stars, are those young stars whose metallicity is highest. The high metallicity of population I stars makes them more likely to possess planetary systems than older populations, because planets form by the accretion of metals.[citation needed] The Sun is an example of a metal-rich star. These are common in the disks of galaxies.[66] Generally, the youngest stars, the extreme population I, are found farther in and intermediate population I stars are farther out, etc. The Sun is considered an intermediate population I star. Population I stars have regular elliptical orbits around the Galactic Center, with a low relative velocity.[67]

Population II, or metal-poor stars, are those with relatively low metallicity which can have hundreds (e.g. BD +17° 3248) or thousands (e.g. Sneden's Star) times less metallicity than the Sun. These objects formed during an earlier time of the universe.[68] Intermediate population II stars are common in the bulge near the center of the Milky Way,[citation needed] whereas Population II stars found in the galactic halo are older and thus more metal-poor.[citation needed] Globular clusters also contain high numbers of population II stars.[69] In 2014, the first planets around a halo star were announced around Kapteyn's star, the nearest halo star to Earth, around 13 light years away. However, later research suggests that Kapteyn b is just an artefact of stellar activity and that Kapteyn c needs more study to be confirmed.[70] The metallicity of Kapteyn's star is estimated to be about 8[e] times less than the Sun.[71]

Different types of galaxies have different histories of star formation and hence planet formation. Planet formation is affected by the ages, metallicities, and orbits of stellar populations within a galaxy. Distribution of stellar populations within a galaxy varies between the different types of galaxies.[72] Stars in elliptical galaxies are much older than stars in spiral galaxies. Most elliptical galaxies contain mainly low-mass stars, with minimal star-formation activity.[73] The distribution of the different types of galaxies in the universe depends on their location within galaxy clusters, with elliptical galaxies found mostly close to their centers.[74]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ For the purpose of this 1 in 5 statistic, "Sun-like" means G-type star. Data for Sun-like stars were not available so this statistic is an extrapolation from data about K-type stars

- ^ For the purpose of this 1 in 5 statistic, Earth-sized means 1–2 Earth radii

- ^ For the purpose of this 1 in 5 statistic, "habitable zone" means the region with 0.25 to 4 times Earth's stellar flux (corresponding to 0.5–2 AU for the Sun).

- ^ For the purpose of this, terrestrial-sized means 0.5–1.4 Earth radii, the "Venus zone" means the region with approximately 1 to 25 times Earth's stellar flux for M and K-type stars and approximately 1.1 to 25 times Earth's stellar flux for G-type stars.

- ^ Metallicity of Kapteyn's star estimated at [Fe/H]= −0.89. 10−0.89 ≈ 1/8

References

[edit]- ^ Darling, David J. (2004). The universal book of astronomy: from the Andromeda Galaxy to the zone of avoidance. Hoboken (NJ): Wiley. p. 394. ISBN 978-0-471-26569-6.

- ^ Illingworth, Valerie, ed. (2000). Collins dictionary astronomy (2 ed.). Glasgow: HarperCollins. p. 314. ISBN 978-0-00-710297-6.

- ^ p. 382, Collins Dictionary of Astronomy.

- ^ Ridpath, Ian, ed. (2003). A dictionary of astronomy. Oxford paperback reference (Rev. ed.). Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press. p. 420. ISBN 978-0-19-860513-3.

- ^ Schneider, J. "Interactive Extra-solar Planets Catalog". The Extrasolar Planets Encyclopedia. Retrieved July 29, 2025.

- ^ "IAU Office of Astronomy for Education". IAU Office of Astronomy for Education. Retrieved July 10, 2025.

- ^ "Solar System: Facts". NASA Science. November 13, 2017. Retrieved July 10, 2025.

- ^ Pierrehumbert, Raymond T. (December 9, 2021). "1. Beginnings". Planetary Systems: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. p. 1–13. doi:10.1093/actrade/9780198841128.003.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-884112-8. Retrieved July 10, 2025.

The term 'planetary system' has begun to gain currency to describe such objects, and it is the term we adopt to refer to a star and all the bodies gravitationally bound to it—the planets whether rocky, gassy, or icy, their moons, the asteroids, comets, and the far flung icy bodies that make up Kuiper Belts. Our own planetary system contains only one star, but other planetary systems commonly contain two or even three stars.

- ^ Dreyer (1953), pp.135–48; Linton (2004), pp.38–9). The work of Aristarchus's in which he proposed his heliocentric system has not survived. We only know of it now from a brief passage in Archimedes's The Sand Reckoner.

- ^ Noel Swerdlow, "Review: A Lost Monument of Indian Astronomy," Isis, 64 (1973): 239–243.

- ^ "Cosmos" in The New Encyclopædia Britannica (15th edition, Chicago, 1991) 16:787:2a. "For his advocacy of an infinity of suns and earths, he was burned at the stake in 1600."

- ^ Newton, Isaac; Cohen, I. Bernard; Whitman, Anne (1999) [First published 1713]. The Principia: A New Translation and Guide. University of California Press. p. 940. ISBN 0-520-20217-1.

- ^ Podsiadlowski, Philipp (1993). "Planet formation scenarios". In: Planets Around Pulsars; Proceedings of the Conference. 36: 149. Bibcode:1993ASPC...36..149P.

- ^ Perna, Rosalba; Duffell, Paul; Cantiello, Matteo; MacFadyen, Andrew (December 17, 2013). "The Fate of Fallback Matter Around Newly Born Compact Objects". The Astrophysical Journal. 781 (2): 119. arXiv:1312.4981. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/781/2/119.

- ^ Miguel, Y; Cridland, A; Ormel, C W; Fortney, J J; Ida, S (October 30, 2019). "Diverse outcomes of planet formation and composition around low-mass stars and brown dwarfs". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society stz3007. arXiv:1909.12320. doi:10.1093/mnras/stz3007. ISSN 0035-8711.

- ^ "Sculpting Solar Systems - ESO's SPHERE instrument reveals protoplanetary discs being shaped by newborn planets". www.eso.org. Retrieved December 7, 2016.

- ^ Ferreira, Becky (May 3, 2023). "It's the End of a World as We Know It - Astronomers spotted a dying star swallowing a large planet, a discovery that fills in a "missing link" in understanding the fates of Earth and many other planets". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 3, 2023. Retrieved May 3, 2023.

- ^ Ferreira, Becky (August 19, 2022). "The Juicy Secrets of Stars That Eat Their Planets - As scientists study thousands of planets around the galaxy, they are learning more about worlds that get swallowed up by their stars". The New York Times. Retrieved August 19, 2022.

- ^ Hasegawa, Yasuhiro; Pudritz, Ralph E. (2011). "The origin of planetary system architectures - I. Multiple planet traps in gaseous discs". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 417 (2): 1236–1259. arXiv:1105.4015. Bibcode:2011MNRAS.417.1236H. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.19338.x. ISSN 0035-8711. S2CID 118843952.

- ^ Stuart J. Weidenschilling & Francesco Marzari (1996). "Gravitational scattering as a possible origin for giant planets at small stellar distances". Nature. 384 (6610): 619–621. Bibcode:1996Natur.384..619W. doi:10.1038/384619a0. hdl:11577/123794. PMID 8967949. S2CID 4304777.

- ^ "We're in the cosmic 1% – planetplanet". February 8, 2021. Retrieved January 25, 2025.

- ^ Types and Attributes at Astro Washington.com.

- ^ Borucki, William J.; Koch, David G.; Basri, Gibor; Batalha, Natalie; Brown, Timothy M.; Bryson, Stephen T.; Caldwell, Douglas; Christensen-Dalsgaard, Jørgen; Cochran, William D.; DeVore, Edna; Dunham, Edward W.; Gautier, Thomas N., III; Geary, John C.; Gilliland, Ronald; Gould, Alan (July 1, 2011). "Characteristics of Planetary Candidates Observed by Kepler. II. Analysis of the First Four Months of Data". The Astrophysical Journal. 736 (1): 19. arXiv:1102.0541. Bibcode:2011ApJ...736...19B. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/736/1/19. ISSN 0004-637X.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Hot Super-Earths (and mini-Neptunes)! – planetplanet". March 3, 2014. Retrieved January 25, 2025.

- ^ Mishra, Lokesh; Alibert, Yann; Udry, Stéphane; Mordasini, Christoph (February 1, 2023). "Framework for the architecture of exoplanetary systems - I. Four classes of planetary system architecture". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 670: A68. arXiv:2301.02374. Bibcode:2023A&A...670A..68M. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202243751. ISSN 0004-6361.

- ^ Mishra, Lokesh; Alibert, Yann; Udry, Stéphane; Mordasini, Christoph (February 1, 2023). "Framework for the architecture of exoplanetary systems - II. Nature versus nurture: Emergent formation pathways of architecture classes". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 670: A69. arXiv:2301.02373. Bibcode:2023A&A...670A..69M. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202244705. ISSN 0004-6361.

- ^ a b Mishra, Lokesh; Alibert, Yann; Leleu, Adrien; Emsenhuber, Alexandre; Mordasini, Christoph; Burn, Remo; Udry, Stéphane; Benz, Willy (December 1, 2021). "The New Generation Planetary Population Synthesis (NGPPS) VI. Introducing KOBE: Kepler Observes Bern Exoplanets - Theoretical perspectives on the architecture of planetary systems: Peas in a pod". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 656: A74. arXiv:2105.12745. Bibcode:2021A&A...656A..74M. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202140761. ISSN 0004-6361.

- ^ Andrew Cumming; R. Paul Butler; Geoffrey W. Marcy; et al. (2008). "The Keck Planet Search: Detectability and the Minimum Mass and Orbital Period Distribution of Extrasolar Planets". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 120 (867): 531–554. arXiv:0803.3357. Bibcode:2008PASP..120..531C. doi:10.1086/588487. S2CID 10979195.

- ^ Bonfils, Xavier; Forveille, Thierry; Delfosse, Xavier; Udry, Stéphane; Mayor, Michel; Perrier, Christian; Bouchy, François; Pepe, Francesco; Queloz, Didier; Bertaux, Jean-Loup (2005). "The HARPS search for southern extra-solar planets VI: A Neptune-mass planet around the nearby M dwarf Gl 581". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 443 (3): L15 – L18. arXiv:astro-ph/0509211. Bibcode:2005A&A...443L..15B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:200500193. S2CID 59569803.

- ^ "The Different Kinds of Exoplanets You Meet in the Milky Way". The Planetary Society. Retrieved October 25, 2025.

- ^ Fortney, Jonathan J.; Dawson, Rebekah I.; Komacek, Thaddeus D. (2021). "Hot Jupiters: Origins, Structure, Atmospheres". Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets. 126 (3) e2020JE006629. arXiv:2102.05064. Bibcode:2021JGRE..12606629F. doi:10.1029/2020JE006629. ISSN 2169-9100.

- ^ "What Is a Super-Earth? - NASA Science". October 22, 2020. Retrieved October 25, 2025.

- ^ Stark, C.; Kuchner, M. (2008). "The Detectability of Exo-Earths and Super-Earths Via Resonant Signatures in Exozodiacal Clouds". The Astrophysical Journal. 686 (1): 637–648. arXiv:0810.2702. Bibcode:2008ApJ...686..637S. doi:10.1086/591442. S2CID 52233547.

- ^ Lebreton, J.; van Lieshout, R.; Augereau, J.-C.; Absil, O.; Mennesson, B.; Kama, M.; Dominik, C.; Bonsor, A.; Vandeportal, J.; Beust, H.; Defrère, D.; Ertel, S.; Faramaz, V.; Hinz, P.; Kral, Q.; Lagrange, A.-M.; Liu, W.; Thébault, P. (2013). "An interferometric study of the Fomalhaut inner debris disk. III. Detailed models of the exozodiacal disk and its origin". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 555: A146. arXiv:1306.0956. Bibcode:2013A&A...555A.146L. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201321415. S2CID 12112032.

- ^ a b Absil, O.; Le Bouquin, J.-B.; Berger, J.-P.; Lagrange, A.-M.; Chauvin, G.; Lazareff, B.; Zins, G.; Haguenauer, P.; Jocou, L.; Kern, P.; Millan-Gabet, R.; Rochat, S.; Traub, W. (2011). "Searching for faint companions with VLTI/PIONIER. I. Method and first results". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 535: A68. arXiv:1110.1178. Bibcode:2011A&A...535A..68A. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201117719. S2CID 13144157.

- ^ di Folco, E.; Absil, O.; Augereau, J.-C.; Mérand, A.; Coudé du Foresto, V.; Thévenin, F.; Defrère, D.; Kervella, P.; ten Brummelaar, T. A.; McAlister, H. A.; Ridgway, S. T.; Sturmann, J.; Sturmann, L.; Turner, N. H. (2007). "A near-infrared interferometric survey of debris disk stars". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 475 (1): 243–250. arXiv:0710.1731. Bibcode:2007A&A...475..243D. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20077625. S2CID 18317389.

- ^ Johnston, Robert (August 2, 2014). "Known populations of solar system objects". Archived from the original on June 9, 2019. Retrieved January 19, 2015.

- ^ Ferlet, R.; Vidal-Madjar, A.; Hobbs, L. M. (1987). "The Beta Pictoris circumstellar disk. V - Time variations of the CA II-K line". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 185: 267–270. Bibcode:1987A&A...185..267F.

- ^ Beust, H.; Lagrange-Henri, A.M.; Vidal-Madjar, A.; Ferlet, R. (1990). "The Beta Pictoris circumstellar disk. X - Numerical simulations of infalling evaporating bodies". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 236: 202–216. Bibcode:1990A&A...236..202B.

- ^ a b Lagrange-Henri, A. M.; Beust, H.; Ferlet, R.; Vidal-Madjar, A.; Hobbs, L. M. (1990). "HR 10 - A new Beta Pictoris-like star?". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 227: L13 – L16. Bibcode:1990A&A...227L..13L.

- ^ a b Lecavelier Des Etangs, A.; et al. (1997). "HST-GHRS observations of candidate β Pictoris-like circumstellar gaseous disks". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 325: 228–236. Bibcode:1997A&A...325..228L.

- ^ a b Welsh, B. Y. & Montgomery, S. (2013). "Circumstellar Gas-Disk Variability Around A-Type Stars: The Detection of Exocomets?". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 125 (929): 759–774. Bibcode:2013PASP..125..759W. doi:10.1086/671757.

- ^ a b Kiefer, F.; Lecavelier Des Etangs, A.; et al. (2014). "Exocomets in the circumstellar gas disk of HD 172555". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 561: L10. arXiv:1401.1365. Bibcode:2014A&A...561L..10K. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201323128. S2CID 118533377.

- ^ "'Exocomets' Common Across Milky Way Galaxy". Space.com. January 7, 2013. Retrieved January 8, 2013.

- ^ "NASA's Spitzer Telescope Witnesses Asteroid Smashup". NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). Retrieved May 17, 2025.

- ^ "Saturn-like ring system eclipses Sun-like star". ScienceDaily. Retrieved May 17, 2025.

Mamajek thinks his team could be either observing the late stages of planet formation if the transiting object is a star or brown dwarf, or possibly moon formation if the transiting object is a giant planet.

- ^ Российские астрономы впервые открыли луну возле экзопланеты (in Russian) – "Studying of a curve of change of shine of WASP-12b has brought to the Russian astronomers unusual result: regular splashes were found out.<...> Though stains on a star surface also can cause similar changes of shine, observable splashes are very similar on duration, a profile and amplitude that testifies for benefit of exomoon existence."

- ^ Dvorak, R.; Pilat-Lohinger, E.; Bois, E.; Schwarz, R.; Funk, B.; Beichman, C.; Danchi, W.; Eiroa, C.; Fridlund, M.; Henning, T.; Herbst, T.; Kaltenegger, L.; Lammer, H.; Léger, A.; Liseau, R.; Lunine, Jonathan I.; Paresce F, Penny, A.; Quirrenbach, A.; Röttgering, H.; Selsis, F.; Schneider, J.; Stam, D.; Tinetti, G.; White, G.; "Dynamical habitability of planetary systems", Institute for Astronomy, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria, January 2010

- ^ Mills, Sean M.; Fabrycky, Daniel C. (2017). "Kepler-108: A Mutually Inclined Giant Planet System". The Astronomical Journal. 153 (1): 45. arXiv:1606.04485. Bibcode:2017AJ....153...45M. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/153/1/45. S2CID 119295498.

- ^ Deitrick, Russell; Barnes, Rory; McArthur, Barbara; Quinn, Thomas R.; Luger, Rodrigo; Antonsen, Adrienne; Fritz Benedict, G. (2014). "The 3-dimensional architecture of the Upsilon Andromedae planetary system". The Astrophysical Journal. 798: 46. arXiv:1411.1059. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/798/1/46. S2CID 118409453.

- ^ "NASA – Out of Whack Planetary System Offers Clues to a Disturbed Past". Nasa.gov. May 25, 2010. Retrieved August 17, 2012.

- ^ Emspak, Jesse (March 2, 2011). "Kepler Finds Bizarre Systems". International Business Times. International Business Times Inc. Retrieved March 2, 2011.

- ^ Winn, Joshua N.; Fabrycky, Daniel C. (2015). "The Occurrence and Architecture of Exoplanetary Systems". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 53: 409–447. arXiv:1410.4199. Bibcode:2015ARA&A..53..409W. doi:10.1146/annurev-astro-082214-122246. S2CID 6867394.

- ^ Fabrycky, Daniel C. (2010). "Non-Keplerian Dynamics". arXiv:1006.3834 [astro-ph.EP].

- ^ Migaszewski, Cezary; Goździewski, Krzysztof (2009). "Equilibria in the secular, non-co-planar two-planet problem". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 395 (4): 1777–1794. arXiv:0812.2949. Bibcode:2009MNRAS.395.1777M. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2009.14552.x. S2CID 14922361.

- ^ Perets, Hagai B.; Kouwenhoven, M. B. N. (March 13, 2012). "On the Origin of Planets at Very Wide Orbits from the Recapture of Free Floating Planets". The Astrophysical Journal. 750 (1): 83. arXiv:1202.2362. Bibcode:2012ApJ...750...83P. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/750/1/83.

- ^ Amend, J. P.; Teske, A. (2005). "Expanding frontiers in deep subsurface microbiology". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 219 (1–2): 131–155. Bibcode:2005PPP...219..131A. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2004.10.018.

- ^ Further away planets 'can support life' say researchers, BBC, January 7, 2014 Last updated at 12:40

- ^ Sanders, R. (November 4, 2013). "Astronomers answer key question: How common are habitable planets?". newscenter.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on November 7, 2014. Retrieved November 6, 2014.

- ^ Petigura, E. A.; Howard, A. W.; Marcy, G. W. (2013). "Prevalence of Earth-size planets orbiting Sun-like stars". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (48): 19273–19278. arXiv:1311.6806. Bibcode:2013PNAS..11019273P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1319909110. PMC 3845182. PMID 24191033.

- ^ Habitable Zone Gallery - Venus

- ^ Kane, Stephen R.; Kopparapu, Ravi Kumar; Domagal-Goldman, Shawn D. (2014). "On the Frequency of Potential Venus Analogs from Kepler Data". The Astrophysical Journal. 794 (1): L5. arXiv:1409.2886. Bibcode:2014ApJ...794L...5K. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/794/1/L5. S2CID 119178082.

- ^ SAG 11: Preparing for the WFIRST Microlensing Survey Archived February 22, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, Jennifer Yee

- ^ Toward a New Era in Planetary Microlensing Archived November 3, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, Andy Gould, September 21, 2010

- ^ Batista, V.; Beaulieu, J. -P.; Gould, A.; Bennett, D. P.; Yee, J. C.; Fukui, A.; Gaudi, B. S.; Sumi, T.; Udalski, A. (2013). "Moa-2011-BLG-293Lb: First Microlensing Planet Possibly in the Habitable Zone". The Astrophysical Journal. 780: 54. arXiv:1310.3706. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/780/1/54.

- ^ "Population I | COSMOS". astronomy.swin.edu.au. Retrieved October 25, 2025.

- ^ Charles H. Lineweaver (2000). "An Estimate of the Age Distribution of Terrestrial Planets in the Universe: Quantifying Metallicity as a Selection Effect". Icarus. 151 (2): 307–313. arXiv:astro-ph/0012399. Bibcode:2001Icar..151..307L. doi:10.1006/icar.2001.6607. S2CID 14077895.

- ^ "Population II | COSMOS". astronomy.swin.edu.au. Retrieved October 25, 2025.

- ^ T. S. van Albada; Norman Baker (1973). "On the Two Oosterhoff Groups of Globular Clusters". Astrophysical Journal. 185: 477–498. Bibcode:1973ApJ...185..477V. doi:10.1086/152434.

- ^ Robertson, Paul; Roy, Arpita; Mahadevan, Suvrath (2015). "Stellar Activity Mimics a Habitable-Zone Planet Around Kapteyn's Star". The Astrophysical Journal. 805 (2): L22. arXiv:1505.02778. Bibcode:2015ApJ...805L..22R. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/805/2/L22.

- ^ Anglada-Escudé, G.; Arriagada, P.; Tuomi, M.; Zechmeister, M.; Jenkins, J. S.; Ofir, A.; Dreizler, S.; Gerlach, E.; Marvin, C. J.; Reiners, A.; Jeffers, S. V.; Butler, R. P.; Vogt, S. S.; Amado, P. J.; Rodríguez-López, C.; Berdiñas, Z. M.; Morin, J.; Crane, J. D.; Shectman, S. A.; Thompson, I. B.; Díaz, M.; Rivera, E.; Sarmiento, L. F.; Jones, H. R. A. (2014). "Two planets around Kapteyn's star: A cold and a temperate super-Earth orbiting the nearest halo red dwarf". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters. 443: L89 – L93. arXiv:1406.0818. doi:10.1093/mnrasl/slu076.

- ^ Gonzalez, Guillermo (2005). "Habitable Zones in the Universe". Origins of Life and Evolution of Biospheres. 35 (6): 555–606. arXiv:astro-ph/0503298. Bibcode:2005OLEB...35..555G. doi:10.1007/s11084-005-5010-8. PMID 16254692.

- ^ Dressler, A. (March 1980). "Galaxy morphology in rich clusters - Implications for the formation and evolution of galaxies". The Astrophysical Journal. 236: 351–365. Bibcode:1980ApJ...236..351D. doi:10.1086/157753.

Further reading

[edit]- Kóspál, Ágnes; Ardila, David R.; Moór, Attila; Ábrahám, Péter (2009). "On the Relationship Between Debris Disks and Planets". The Astrophysical Journal. 700 (2): L73 – L77. arXiv:astro-ph/0007014. Bibcode:2000ApJ...537L.147O. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/700/2/L73. S2CID 16636256.

- Ozernoy, Leonid M.; Gorkavyi, Nick N.; Mather, John C.; Taidakova, Tanya A. (2000). "Signatures of Exosolar Planets in Dust Debris Disks". The Astrophysical Journal. 537 (2): L147 – L151. arXiv:0907.0028. Bibcode:2009ApJ...700L..73K. doi:10.1086/312779. S2CID 1149097.