Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Object database

View on Wikipedia

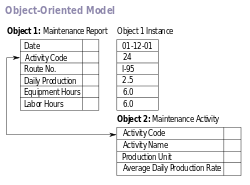

An object database or object-oriented database is a database management system in which information is represented in the form of objects as used in object-oriented programming. Object databases are different from relational databases which are table-oriented. A third type, object–relational databases, is a hybrid of both approaches. Object databases have been considered since the early 1980s.[2]

Overview

[edit]Object-oriented database management systems (OODBMSs) also called ODBMS (Object Database Management System) combine database capabilities with object-oriented programming language capabilities. OODBMSs allow object-oriented programmers to develop the product, store them as objects, and replicate or modify existing objects to make new objects within the OODBMS. Because the database is integrated with the programming language, the programmer can maintain consistency within one environment, in that both the OODBMS and the programming language will use the same model of representation. Relational DBMS projects, by way of contrast, maintain a clearer division between the database model and the application.

As the usage of web-based technology increases with the implementation of Intranets and extranets, companies have a vested interest in OODBMSs to display their complex data. Using a DBMS that has been specifically designed to store data as objects gives an advantage to those companies that are geared towards multimedia presentation or organizations that utilize computer-aided design (CAD).[3]

Some object-oriented databases are designed to work well with object-oriented programming languages such as Delphi, Ruby, Python, JavaScript, Perl, Java, C#, Visual Basic .NET, C++, Objective-C and Smalltalk; others such as JADE have their own programming languages. OODBMSs use exactly the same model as object-oriented programming languages.

History

[edit]Object database management systems grew out of research during the early to mid-1970s into having intrinsic database management support for graph-structured objects. The term "object-oriented database system" first appeared around 1985.[4] Notable research projects included Encore-Ob/Server (Brown University), EXODUS (University of Wisconsin–Madison), IRIS (Hewlett-Packard), ODE (Bell Labs), ORION (Microelectronics and Computer Technology Corporation or MCC), Vodak (GMD-IPSI), and Zeitgeist (Texas Instruments). The ORION project had more published papers than any of the other efforts. Won Kim of MCC compiled the best of those papers in a book published by The MIT Press.[5]

Early commercial products included Gemstone (Servio Logic, name changed to GemStone Systems), Gbase (Graphael), and Vbase (Ontologic). Additional commercial products entered the market in the late 1980s through the mid 1990s. These included ITASCA (Itasca Systems), Jasmine (Fujitsu, marketed by Computer Associates), Matisse (Matisse Software), Objectivity/DB (Objectivity, Inc.), ObjectStore (Progress Software, acquired from eXcelon which was originally Object Design, Incorporated), ONTOS (Ontos, Inc., name changed from Ontologic), O2[6] (O2 Technology, merged with several companies, acquired by Informix, which was in turn acquired by IBM), POET (now FastObjects from Versant which acquired Poet Software), Versant Object Database (Versant Corporation), VOSS (Logic Arts) and JADE (Jade Software Corporation). Some of these products remain on the market and have been joined by new open source and commercial products such as InterSystems Caché.

Object database management systems added the concept of persistence to object programming languages. The early commercial products were integrated with various languages: GemStone (Smalltalk), Gbase (LISP), Vbase (COP) and VOSS (Virtual Object Storage System for Smalltalk). For much of the 1990s, C++ dominated the commercial object database management market. Vendors added Java in the late 1990s and more recently, C#.

Starting in 2004, object databases have seen a second growth period when open source object databases emerged that were widely affordable and easy to use, because they are entirely written in OOP languages like Smalltalk, Java, or C#, such as Versant's db4o (db4objects), DTS/S1 from Obsidian Dynamics and Perst (McObject), available under dual open source and commercial licensing.

Timeline

[edit]- 1966

- 1979

- 1980

- 1982

- Gemstone started (as Servio Logic) to build a set theoretic model data base machine.

- 1985 – Term Object Database first introduced

- 1986

- Servio Logic (Gemstone Systems) Ships Gemstone 1.0

- 1988

- Object Design, Incorporated founded, development of ObjectStore begun

- Versant Corporation started (as Object Sciences Corp)

- Objectivity, Inc. founded

- Early 1990s

- Mid 1990s

- InterSystems Caché

- Versant Object Database

- ODABA

- ZODB

- Poet

- JADE

- Matisse

- Illustra Informix

- 2000s

- lambda-DB: An ODMG-Based Object-Oriented DBMS by Leonidas Fegaras, Chandrasekhar Srinivasan, Arvind Rajendran, David Maier

- db4o project started by Carl Rosenberger

- ObjectDB

- 2001 IBM acquires Informix

- 2003 odbpp public release

- 2004 db4o's commercial launch as db4objects, Inc.

- 2008 db4o acquired by Versant Corporation

- 2010 VMware acquires GemStone[8]

- 2011 db4o's development stopped.

- 2012 Wakanda first production versions with open source and commercial licenses

- 2012 Actian acquires Versant Corporation

- 2013 GemTalk Systems acquires Gemstone products from VMware[9]

- 2014 db4o's commercial offering is officially discontinued by Actian (which had acquired Versant)[10]

- 2014 Realm[11]

- 2017 ObjectBox[12]

Adoption of object databases

[edit]Object databases based on persistent programming acquired a niche in application areas such as engineering and spatial databases, telecommunications, and scientific areas such as high energy physics[13] and molecular biology.[14]

Another group of object databases focuses on embedded use in devices, packaged software, and real-time systems.

Technical features

[edit]Most object databases also offer some kind of query language, allowing objects to be found using a declarative programming approach. It is in the area of object query languages, and the integration of the query and navigational interfaces, that the biggest differences between products are found. An attempt at standardization was made by the ODMG with the Object Query Language, OQL.

Access to data can be faster because an object can be retrieved directly without a search, by following pointers.

Another area of variation between products is in the way that the schema of a database is defined. A general characteristic, however, is that the programming language and the database schema use the same type definitions.

Multimedia applications are facilitated because the class methods associated with the data are responsible for its correct interpretation.

Many object databases, for example Gemstone or VOSS, offer support for versioning. An object can be viewed as the set of all its versions. Also, object versions can be treated as objects in their own right. Some object databases also provide systematic support for triggers and constraints which are the basis of active databases.

The efficiency of such a database is also greatly improved in areas which demand massive amounts of data about one item. For example, a banking institution could get the user's account information and provide them efficiently with extensive information such as transactions, account information entries etc.

Standards

[edit]The Object Data Management Group was a consortium of object database and object–relational mapping vendors, members of the academic community, and interested parties. Its goal was to create a set of specifications that would allow for portable applications that store objects in database management systems. It published several versions of its specification. The last release was ODMG 3.0. By 2001, most of the major object database and object–relational mapping vendors claimed conformance to the ODMG Java Language Binding. Compliance to the other components of the specification was mixed. In 2001, the ODMG Java Language Binding was submitted to the Java Community Process as a basis for the Java Data Objects specification. The ODMG member companies then decided to concentrate their efforts on the Java Data Objects specification. As a result, the ODMG disbanded in 2001.

Many object database ideas were also absorbed into SQL:1999 and have been implemented in varying degrees in object–relational database products.

In 2005 Cook, Rai, and Rosenberger proposed to drop all standardization efforts to introduce additional object-oriented query APIs but rather use the OO programming language itself, i.e., Java and .NET, to express queries. As a result, Native Queries emerged. Similarly, Microsoft announced Language Integrated Query (LINQ) and DLINQ, an implementation of LINQ, in September 2005, to provide close, language-integrated database query capabilities with its programming languages C# and VB.NET 9.

In February 2006, the Object Management Group (OMG) announced that they had been granted the right to develop new specifications based on the ODMG 3.0 specification and the formation of the Object Database Technology Working Group (ODBT WG). The ODBT WG planned to create a set of standards that would incorporate advances in object database technology (e.g., replication), data management (e.g., spatial indexing), and data formats (e.g., XML) and to include new features into these standards that support domains where object databases are being adopted (e.g., real-time systems). The work of the ODBT WG was suspended in March 2009 when, subsequent to the economic turmoil in late 2008, the ODB vendors involved in this effort decided to focus their resources elsewhere.

In January 2007 the World Wide Web Consortium gave final recommendation status to the XQuery language. XQuery uses XML as its data model. Some of the ideas developed originally for object databases found their way into XQuery, but XQuery is not intrinsically object-oriented. Because of the popularity of XML, XQuery engines compete with object databases as a vehicle for storage of data that is too complex or variable to hold conveniently in a relational database. XQuery also allows modules to be written to provide encapsulation features that have been provided by Object-Oriented systems.

XQuery v1 and XPath v2 and later are powerful and are available in both open source and libre (FOSS) software,[15][16][17] as well as in commercial systems. They are easy to learn and use, and very powerful and fast. They are not relational and XQuery is not based on SQL (although one of the people who designed XQuery also co-invented SQL). But they are also not object-oriented, in the programming sense: XQuery does not use encapsulation with hiding, implicit dispatch, and classes and methods. XQuery databases generally use XML and JSON as an interchange format, although other formats are used.

Since the early 2000s JSON has gained community adoption and popularity in applications where developers are in control of the data format. JSONiq, a query-analog of XQuery for JSON (sharing XQuery's core expressions and operations), demonstrated the functional equivalence of the JSON and XML formats for data-oriented information. In this context, the main strategy of OODBMS maintainers was to retrofit JSON to their databases (by using it as the internal data type).

In January 2016, with the PostgreSQL 9.5 release[18] was the first FOSS OODBMS to offer an efficient JSON internal datatype (JSONB) with a complete set of functions and operations, for all basic relational and non-relational manipulations.

Comparison with RDBMSs

[edit]An object database stores complex data and relationships between data directly, without mapping to relational rows and columns, and this makes them suitable for applications dealing with very complex data.[19] Objects have a many-to-many relationship and are accessed by the use of pointers. Pointers are linked to objects to establish relationships. Another benefit of an OODBMS is that it can be programmed with small procedural differences without affecting the entire system.[20]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Data Integration Glossary Archived March 20, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, U.S. Department of Transportation, August 2001.

- ^ ODBMS.ORG :: Object Database (ODBMS) | Object-Oriented Database (OODBMS) | Free Resource Portal. ODBMS (2013-08-31). Retrieved on 2013-09-18. Archived March 6, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ O’Brien, J. A., & Marakas, G. M. (2009). Management Information Systems (9th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill/Irwin

- ^ Three example references from 1985 that use the term: T. Atwood, "An Object-Oriented DBMS for Design Support Applications", Proceedings of the IEEE COMPINT 85, pp. 299-307, September 1985; N. Derrett, W. Kent, and P. Lyngbaek, "Some Aspects of Operations in an Object-Oriented Database", Database Engineering, vol. 8, no. 4, IEEE Computer Society, December 1985; D. Maier, A. Otis, and A. Purdy, "Object-Oriented Database Development at Servio Logic", Database Engineering, vol. 18, no.4, December 1985.

- ^ Kim, Won. Introduction to Object-Oriented Databases. The MIT Press, 1990. ISBN 0-262-11124-1

- ^ Bancilhon, Francois; Delobel, Claude; and Kanellakis, Paris. Building an Object-Oriented Database System: The Story of O2. Morgan Kaufmann Publishers, 1992. ISBN 1-55860-169-4.

- ^ Ulfsby; et al. (July 1981). "TORNADO: a DBMS for CAD/CAM systems". Computer-Aided Design. 13 (4): 193–197. doi:10.1016/0010-4485(81)90140-8.

- ^ "SpringSource to Acquire Gemstone Systems Data Management Technology". WMware. May 6, 2010. Archived from the original on August 8, 2014. Retrieved August 5, 2014.

- ^ GemTalk Systems (May 2, 2013). "GemTalk Systems Acquires GemStone/S Products from VMware". PRWeb. Archived from the original on August 10, 2014. Retrieved August 5, 2014.

- ^ "restructuring our Versant Community Website".

- ^ "Realm Releases Object Database for Node.js". InfoQ. Archived from the original on 2017-02-02.

- ^ DB-Engines. "Object Database Ranking on DB-Engines". DB-Engines. Retrieved 2021-05-21.

- ^ "Stanford Linear Accelerator (SLAC)".

- ^ Herde, Patrick; Sibbald, Peter R. (1992). "Integration of molecular biology data collections using object oriented databases and programming". Addendum to the proceedings on Object-oriented programming systems, languages, and applications (Addendum) - OOPSLA '92. pp. 177–178. doi:10.1145/157709.157747. ISBN 0897916107. S2CID 45269462.

- ^ "BaseX XQuery Processor". basex.org. Archived from the original on 2023-12-16.

- ^ "XQuery in eXist-db". exist-db.org. Archived from the original on 2023-12-02.

- ^ "Saxon - Using XQuery". www.saxonica.com. Archived from the original on 2020-09-23.

- ^ "PostgreSQL: Documentation: 10: 9.15. JSON Functions and Operators". www.postgresql.org. Archived from the original on 2016-05-18.

- ^ Radding, Alan (1995). "So what the Hell is ODBMS?". Computerworld. 29 (45): 121–122, 129.

- ^ Burleson, Donald. (1994). OODBMSs gaining MIS ground but RDBMSs still own the road. Software Magazine, 14(11), 63

External links

[edit]- Object DBMS resource portal

- Ranking of Object Oriented DBMS Archived 2024-12-01 at the Wayback Machine - by popularity, updated monthly from DB-Engines

Object database

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Principles

An object database, also known as an object-oriented database management system (OODBMS), is a database management system that stores and manages data in the form of objects, directly incorporating attributes, methods, and inheritance structures that align with object-oriented programming paradigms.[5] Unlike traditional databases that decompose data into flat records, object databases treat entities as self-contained units with both state (data) and behavior (operations), enabling a unified approach to data modeling and manipulation.[6] The core principles of object databases revolve around encapsulation, polymorphism, and inheritance, which extend object-oriented concepts to persistent data storage and retrieval. Encapsulation confines an object's internal data and methods within a single boundary, restricting external access to protect integrity and promote modularity during storage operations.[7] Polymorphism permits objects of varying types to respond to the same operation in type-specific ways, facilitating flexible retrieval and dynamic binding of methods across the database.[5] Inheritance allows subclasses to derive attributes and behaviors from superclasses, supporting hierarchical organization of data and enabling efficient reuse in query and update processes.[6] These principles ensure that complex, interconnected data structures—such as graphs or networks—can be stored and accessed without fragmentation into simpler components. A key feature of object databases is the persistence of objects as first-class database entities, where objects retain their unique identity, state, and associated methods beyond the lifespan of individual applications. This is managed through dedicated storage mechanisms that make objects available across sessions, integrating seamlessly with programming environments.[5] By storing objects natively, object databases eliminate the impedance mismatch—the paradigm gap between object-oriented application logic and data storage formats—that complicates mapping in other systems, thereby reducing conversion overhead and enhancing developer productivity.[8] At a high level, the architecture of an object database includes an object store for holding persistent data, often structured as interconnected object graphs that may be schema-less for flexibility or schema-based for enforced consistency. Objects are linked through references—essentially pointers—that enable direct navigation and traversal of relationships, bypassing attribute-based searches or joins for efficient access to related entities.[6] This reference-based navigation preserves the semantic richness of object-oriented designs in the persistent layer.[5]Advantages and Disadvantages

Object databases provide seamless integration with object-oriented programming (OOP) languages, allowing developers to persist objects directly without the impedance mismatch of object-relational mapping, which significantly reduces development time and effort.[9] This direct mapping preserves the semantics of OOP constructs like inheritance and encapsulation, enabling more intuitive data handling in applications built around object models.[10] They excel in managing complex, hierarchical data structures, such as multimedia content or computer-aided design (CAD) models, where objects can encapsulate both data and behavior, avoiding the need to decompose entities into flat tables.[11] Navigation through interconnected object graphs via object identifiers (OIDs) and pointers facilitates faster traversal and retrieval compared to join operations in relational databases, particularly for pointer-based relationships.[10] Despite these strengths, object databases suffer from the absence of a universally standardized querying language, similar to SQL, resulting in vendor-specific query mechanisms that promote lock-in and hinder portability across systems.[10] Scalability poses challenges for very large datasets, as limited query optimization for complex data types and path expressions can lead to performance degradation under high transaction volumes, often making relational systems more suitable for massive-scale operations.[10] Additionally, the navigational access paradigm requires familiarity with OOP principles, creating a steeper learning curve for developers accustomed to declarative querying in relational environments.[9] A notable trade-off lies in balancing ACID compliance with schema evolution flexibility. Object databases generally uphold ACID properties to ensure transaction reliability, but their support for dynamic schema changes—such as redefining classes or hierarchies with automatic propagation to instances—can incur costs like reorganization overhead in some implementations, potentially straining consistency during evolution compared to the rigid but stable schemas of relational databases.[12] This flexibility, however, surpasses that of relational systems, enabling adaptive modeling without downtime for structural alterations.[11] In applications where these advantages dominate, such as real-time systems requiring low-latency object navigation or graph-like data scenarios involving intricate relationships, object databases prove particularly effective; for example, in CAD environments, hierarchical object persistence streamlines design iterations, while in multimedia systems, integrated object methods enhance processing of composite media assets.[11]History and Evolution

Origins and Early Developments

The origins of object databases trace back to the 1970s, amid efforts to develop semantic data models that better captured real-world complexities beyond the rigid structures of hierarchical and network databases prevalent at the time. The Entity-Relationship (ER) model, proposed by Peter Chen in 1976, marked a significant advancement by introducing high-level abstractions for entities, relationships, attributes, and semantic constructs like aggregation and generalization, which laid foundational concepts for representing objects and their interactions in databases. This model addressed motivations in industry for integrating disparate data formats and enforcing business rules, influencing later object-oriented approaches by emphasizing domain semantics over low-level implementation details.[13] The 1980s saw object databases emerge as a direct response to the limitations of relational databases, introduced by E. F. Codd in 1970, which excelled at managing simple, normalized data but faltered with complex, structured objects involving inheritance, methods, and deep nesting—challenges amplified by the growing adoption of object-oriented programming languages like Smalltalk (developed in the 1970s) and C++ (introduced in 1983). Researchers highlighted how relational models' tuple-based structure and declarative query focus created difficulties in persisting and querying OOP constructs, motivating the design of databases that natively supported object identity, encapsulation, and behavioral semantics to bridge this gap. Key critiques from Codd's successors and contemporaries underscored the relational paradigm's inadequacy for engineering and multimedia applications requiring rich type systems and version control.[14] Early prototypes exemplified these innovations; the IRIS system, developed at Hewlett-Packard Laboratories starting in the early 1980s and detailed in a 1987 publication, introduced an object-oriented data model with support for complex types, inverse references, and query capabilities tailored to OOP environments. GemStone, one of the first commercial systems released in 1987 by Servio Logic, extended Smalltalk's object model into a persistent store, enabling distributed transactions and associative access without impedance issues.[15] In the late 1980s, dedicated research groups accelerated progress through academic and collaborative projects, such as the EXODUS initiative at the University of Wisconsin-Madison (launched in 1986) for building extensible object managers, the Orion project at Microelectronics and Computer Technology Corporation (initiated in the early 1980s) focusing on schema evolution and rule integration, and the O2 project in France emphasizing type-safe object manipulation. These efforts, often building on semantic foundations like the ER model, prioritized seamless integration with OOP languages to handle real-time and design-oriented applications.[16]Key Milestones and Timeline

The development of object databases accelerated in the 1990s through collaborative efforts to standardize interfaces and the introduction of commercial systems tailored for object-oriented applications. Industry leaders recognized the need for interoperability amid growing interest in persistent object storage, leading to key organizational formations and specification releases that influenced product development.[3] By the mid-1990s, several vendors released mature products supporting C++ and early Java bindings, aligning with the ODMG framework to facilitate adoption in complex domains like telecommunications and CAD. The late 1990s saw peak market growth during the dot-com boom, with object databases handling dynamic data structures more natively than relational systems, though interest waned after 2001 as relational DBMS matured and object-relational hybrids gained traction. Conferences such as OOPSLA played a pivotal role, hosting panels and papers on object persistence that advanced research and practical implementations.[17][18] The following timeline highlights major events from 1991 to 2017, focusing on standards, product launches, and industry consolidations:| Year | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1991 | Formation of the Object Data Management Group (ODMG) | Conceived by Rick Cattell of Sun Microsystems, the ODMG was established by leading vendors including Object Design, Objectivity, POET, Versant, and others to define a standard for object databases, promoting portability across systems.[19] |

| 1993 | Release of ODMG 1.0 standard | The inaugural ODMG specification outlined a common architecture, data model, and languages including Object Definition Language (ODL) and Object Query Language (OQL), marking the first industry-wide effort for object database standardization.[20] |

| 1993 | Launch of POET object database | POET Software introduced its C++-based persistent object management system, emphasizing encapsulation and inheritance for applications requiring direct object storage.[21] |

| 1993 | Commercial availability of Objectivity/DB enhancements | Objectivity, Inc. expanded its 1990 initial release with distributed capabilities, targeting large-scale data environments in defense and science. |

| 1994 | Versant Object Database version 3.0 release | Versant Corporation delivered an updated ODBMS with improved scalability and ODMG compliance, building on its earlier foundations for enterprise use.[22] |

| 1995 | ODMG 1.2 maintenance release | This update refined OQL syntax and bindings for C++ and Smalltalk, enhancing vendor implementations and query expressiveness.[23] |

| 1997 | Release of ODMG 2.0 | The updated standard introduced Java bindings and expanded the object model for better integration with emerging languages, adopted by major vendors.[17] |

| 1997 | Introduction of InterSystems Caché as object-capable DBMS | InterSystems launched Caché with multidimensional storage and object interfaces, bridging relational and object paradigms for real-time applications.[24] |

| 2000 | Market peak for commercial ODBMS | Global sales reached approximately $100 million, fueled by dot-com demand for flexible data handling in web and e-commerce systems.[20] |

| 2001 | ODMG 3.0 final release | The last major revision added C# support and clarified mappings, after which the group disbanded amid shifting industry focus.[25] |

| 2001 | Post-dot-com decline begins | Following the 2001 bust, ODBMS adoption slowed as mature RDBMS tools like SQL extensions dominated, reducing pure object database investments.[18] |

| 2003 | Merger of Versant and POET | The two companies combined to form a stronger player in object persistence, integrating technologies for enhanced Java and .NET support.[26] |

| 2008 | Versant acquires db4o | Versant integrated the lightweight Java object database db4o, expanding its portfolio for embedded and mobile applications.[27] |

| 2012 | Actian acquires Versant | Actian Corporation purchased Versant, rebranding its object database as Actian NoSQL to bolster big data offerings.[28] |

| 2017 | Launch of InterSystems IRIS | InterSystems introduced IRIS as the next-generation data platform succeeding Caché, enhancing object-oriented capabilities with multi-model support including analytics and interoperability.[29] |

Technical Architecture

Data Modeling and Objects

In object databases, data modeling revolves around representing information as objects that encapsulate both state and behavior, directly mirroring object-oriented programming paradigms. Objects are instances with a unique identity, typically managed through object identifiers (OIDs), and consist of attributes that hold data values—ranging from simple atomic types like integers or strings to complex structured literals—and methods that define operations on that data.[25] These attributes can be single-valued or multivalued collections, while methods enable encapsulation by bundling behavior with the object's state, allowing for persistent storage without separating data from logic.[30] For instance, a class might define an "Employee" object with attributes such as name (string) and salary (float), alongside methods like computeBonus() to process salary adjustments.[31] Inheritance forms a cornerstone of object database modeling, enabling the creation of type hierarchies that promote reuse and abstraction. Most systems support single inheritance for state, where a subclass extends a superclass to inherit attributes and methods, forming a linear hierarchy; for example, a "Manager" class might extend "Employee" to add supervisory attributes while retaining base functionality.[25] Multiple inheritance is often limited to behavioral aspects via interfaces, avoiding conflicts in state inheritance, though some implementations permit it with resolution mechanisms like prioritization.[30] This structure supports polymorphism, where objects of different types in the same hierarchy can be treated uniformly, facilitating flexible querying and navigation across subtypes without explicit type casting.[31] Relationships between objects are modeled through references and collections, preserving the interconnected nature of real-world entities without flattening into tables. Object references act as direct pointers (e.g., OID-based links) for one-to-one or one-to-many associations, ensuring referential integrity by automatically updating inverses; for example, an "Employee" object might reference a "Department" via a single reference attribute.[25] Collections handle multivalued links, such as sets (unordered, unique elements), lists (ordered sequences), bags (unordered with duplicates), or arrays (fixed-size indexed), enabling patterns like composition—where contained objects are owned and lifecycle-managed by the parent—or aggregation, where referenced objects exist independently.[30] These mechanisms support bidirectional navigation, as in a "Project" class with a set of "Task" references and an inverse "assignedTo" relationship back to the project.[31] Schema management in object databases emphasizes flexibility, contrasting with more rigid relational approaches by supporting both dynamic and static schemas. Static schemas enforce predefined structures via languages like ODL (Object Definition Language), where classes, attributes, and relationships are declared upfront in modules with extents defining instance collections.[25] Dynamic schemas allow runtime modifications, such as adding attributes or altering inheritance, through evolution mechanisms that propagate changes to existing instances without system downtime or full reorganization.[32] For example, evolving a class to include a new relationship might automatically migrate persistent objects, preserving data integrity via versioning or delayed binding, as implemented in systems adhering to standards like ODMG.[33] This approach facilitates ongoing adaptation to application needs while maintaining type safety.[34]Persistence and Querying Mechanisms

Object databases employ persistence strategies that enable the long-term storage of objects without requiring explicit save operations from the application developer. Transparent persistence is a core mechanism, where objects are automatically persisted upon modification, integrating seamlessly with object-oriented programming languages by treating persistent and transient objects uniformly. This approach minimizes code intrusion, allowing developers to work with objects as if they were in-memory, while the database management system (DBMS) handles serialization and storage behind the scenes. For performance enhancement, clustering groups related objects—such as those connected via inheritance or composition—into contiguous storage units on disk, reducing I/O overhead during retrieval of interconnected data structures. Caching complements this by maintaining frequently accessed objects in memory, employing strategies like least-recently-used (LRU) eviction to balance memory usage and hit rates, thereby accelerating access in client-server architectures.[35][36][37] Querying in object databases supports both navigational and declarative paradigms to traverse and retrieve complex object graphs. Navigation-based queries leverage object pointers or references to follow relationships directly, enabling efficient traversal from one object to related ones without declarative specifications, which is particularly suited for hierarchical or network-structured data. Declarative querying, exemplified by the Object Query Language (OQL), allows users to express path expressions and joins over objects using a syntax reminiscent of SQL but extended for object semantics, such as selecting collections of objects based on methods or attributes. OQL facilitates queries like retrieving all employees in a department via path traversals (e.g., department.employees where salary > threshold), supporting aggregation and iteration over object sets. These mechanisms handle the impedance mismatch between object models and storage by optimizing for graph-like access patterns.[38][39][40] Transaction models in object databases adapt the ACID properties—atomicity, consistency, isolation, and durability—to manage concurrent operations on interconnected objects. Atomicity ensures that all changes within a transaction, including creations, updates, and deletions across object graphs, are treated as a single unit, with rollback capabilities to maintain integrity in case of failures. Consistency is enforced through object invariants and constraints, while isolation prevents interference via mechanisms like multi-granularity locking, where locks can be applied at object, class, or collection levels to allow fine-grained concurrency. Durability is achieved by logging changes to non-volatile storage, often using write-ahead logging to recover committed transactions post-crash. Concurrency control typically employs object locking protocols, such as two-phase locking adapted for nested transactions, to handle shared and exclusive access in cooperative or long-running scenarios common in object-oriented applications.[41][42][43] Indexing and optimization techniques in object databases address the challenges of querying complex, graph-structured data by extending traditional structures for object semantics. B-tree variants, such as multi-dimensional or path-indexed B-trees, index object attributes, methods, or relationship paths, enabling efficient range queries and traversals over clustered objects. For instance, universal B-trees support indexing on composite keys derived from object identities and attributes, facilitating quick lookups in inheritance hierarchies. Query optimization involves rewriting declarative queries into navigational plans, estimating costs for graph traversals using statistics on object connectivity, and applying heuristics like join ordering or clustering-aware selectivity to minimize disk accesses. Techniques for graph traversal optimization, including bidirectional search or caching intermediate results, further enhance performance by reducing the exponential complexity of exploring deep object networks.[44][45][46]Standards and Specifications

ODMG Standard

The Object Data Management Group (ODMG) was formed in the summer of 1991 as a non-profit consortium of object database vendors, initiated by Rick Cattell of Sun Microsystems during a meeting with industry leaders to address the lack of standardization in object-oriented database management systems (ODBMS).[16] The group's primary goal was to develop a common specification enabling application portability across different ODBMS products, thereby reducing vendor lock-in and promoting interoperability.[47] The ODMG released its first specification, version 1.0, in August 1993, followed by version 1.2 in November 1995, version 2.0 in April 1997, and the final version 3.0 in 2000.[47][48] These iterations progressively refined the standard, with version 2.0 introducing Java bindings and certification processes for compliance, while version 3.0 enhanced support for object-relational mappings and stabilized the specification without major overhauls.[49] The core components of the ODMG standard include the Object Definition Language (ODL), the Object Query Language (OQL), and language bindings that serve as the Object Programming Language (OPL) interfaces for specific programming languages. ODL is a declarative language for defining database schemas, extending the Object Management Group (OMG) Interface Definition Language (IDL) to specify classes, interfaces, relationships, and attributes in a programming-language-independent manner.[47] OQL provides a declarative query mechanism modeled after SQL but adapted for objects, supporting path expressions, collections, and integration with host programming languages to retrieve and manipulate persistent objects.[47] The OPL bindings, particularly for C++ (introduced in version 1.0) and Java (added in version 2.0), define APIs for creating, storing, and accessing persistent objects directly within the host language, including mechanisms for transactions and exception handling.[47][49] Key features of the ODMG architecture encompass a shared object model that defines basic constructs like objects, literals, collections, and relationships; a storage system for persistence by reachability; and a query processor for executing OQL statements. The object model supports complex types, inheritance, and operations while ensuring compatibility with OMG's Common Object Request Broker Architecture (CORBA). The standard also includes built-in support for collection types such as sets, lists, bags, and arrays, along with exception handling for errors in transactions and queries, facilitating robust object persistence across distributed environments.[47] The ODMG standard saw significant adoption among major ODBMS vendors, including Objectivity, Versant, POET, and Jasmine, who became active members and committed to implementing compliant interfaces in their products by the mid-1990s.[19] This led to widespread conformance claims, particularly for the Java binding by 2001, influencing object-relational mapping tools and enabling portable applications in domains like telecommunications and CAD. However, the group disbanded in 2001 after releasing version 3.0, entering dormancy due to the rise of relational dominance, lack of further updates, and the emergence of alternative standards like Java Data Objects (JDO), limiting its evolution beyond the early 2000s.[3][49]Other Related Standards

In addition to the core ODMG framework, several standards have emerged to support object-relational mapping and hybrid persistence mechanisms, particularly through extensions to established database access protocols. The SQL:1999 standard, also known as SQL3, introduced persistent complex types such as structured user-defined types (UDTs), arrays, multisets, and reference types, enabling relational databases to store and manipulate object-like data with inheritance and methods.[50] These features facilitate object-relational mapping by allowing objects to be persisted as rows with complex attributes, bridging pure object databases and relational systems.[51] JDBC and ODBC, as call-level interfaces, were extended to handle these SQL:1999 constructs; for instance, JDBC 3.0 and later versions support mapping Java objects to SQL structured types via theSQLData interface and Struct class, while ODBC drivers in compliant systems like those adhering to ISO/IEC 9075-3 (SQL/CLI) enable access to UDTs and collections through parameterized queries.[52]

The Unified Modeling Language (UML) and Meta-Object Facility (MOF) provide foundational standards for object modeling that extend to database design and persistence. UML class diagrams serve as a visual notation for defining object schemas in databases, representing entities as classes with attributes, operations, and associations that can map to persistent storage, including support for inheritance and composition in object-oriented database management systems (OODBMS).[53] MOF, an OMG standard, acts as a meta-modeling architecture to define and interchange object models, including those for databases, by providing a four-layer hierarchy where database schemas (M1 level) conform to meta-models (M2 level) like UML, ensuring interoperability for persistent object definitions across tools and repositories.[54]

Following the decline in adoption of pure object databases after the ODMG era, the Java Persistence API (JPA) emerged as a key standard for object persistence, primarily in relational contexts through object-relational mapping (ORM). Introduced in JSR-220 as part of Java EE 5 in 2006, JPA standardizes the mapping of Java objects to relational tables using annotations and XML descriptors for entities, relationships, and lifecycle callbacks, allowing transparent persistence without vendor-specific code.[55] Hibernate, while not a formal standard, has become a de facto implementation of JPA, widely adopted for its robust ORM capabilities that handle object navigation, lazy loading, and caching in relational databases, influencing post-ODMG practices by prioritizing hybrid persistence over native object stores.[56]

The Object Constraint Language (OCL), an OMG standard complementary to UML, specifies integrity constraints for object models, including those in database contexts, to enforce business rules without altering the schema. OCL expressions, written as invariants, pre- and post-conditions, define constraints on object attributes and associations—such as multiplicity checks or derivation rules—ensuring data consistency in persistent object systems during runtime evaluation.[57] In object database applications, OCL integrates with modeling tools to validate constraints on persistent classes, supporting formal verification of integrity beyond what query languages like OQL provide.[58]