Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Software release life cycle

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2025) |

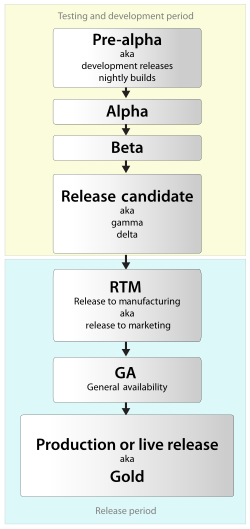

The software release life cycle is the process of developing, testing, and distributing a software product (e.g., an operating system). It typically consists of several stages, such as pre-alpha, alpha, beta, and release candidate, before the final version, or "gold", is released to the public.

Pre-alpha refers to the early stages of development, when the software is still being designed and built. Alpha testing is the first phase of formal testing, during which the software is tested internally using white-box techniques. Beta testing is the next phase, in which the software is tested by a larger group of users, typically outside of the organization that developed it. The beta phase is focused on reducing impacts on users and may include usability testing.

After beta testing, the software may go through one or more release candidate phases, in which it is refined and tested further, before the final version is released.

Some software, particularly in the internet and technology industries, is released in a perpetual beta state, meaning that it is continuously being updated and improved, and is never considered to be a fully completed product. This approach allows for a more agile development process and enables the software to be released and used by users earlier in the development cycle.

Stages of development

[edit]Pre-alpha

[edit]Pre-alpha refers to all activities performed during the software project before formal testing. These activities can include requirements analysis, software design, software development, and unit testing. In typical open source development, there are several types of pre-alpha versions. Milestone versions include specific sets of functions and are released as soon as the feature is complete.[citation needed]

Alpha

[edit]The alpha phase of the release life cycle is the first phase of software testing (alpha is the first letter of the Greek alphabet, used as the number 1). In this phase, developers generally test the software using white-box techniques. Additional validation is then performed using black-box or gray-box techniques, by another testing team. Moving to black-box testing inside the organization is known as alpha release.[1][2]

Alpha software is not thoroughly tested by the developer before it is released to customers. Alpha software may contain serious errors, and any resulting instability could cause crashes or data loss.[3] Alpha software may not contain all of the features that are planned for the final version.[4] In general, external availability of alpha software is uncommon for proprietary software, while open source software often has publicly available alpha versions. The alpha phase usually ends with a feature freeze, indicating that no more features will be added to the software. At this time, the software is said to be feature-complete. A beta test is carried out following acceptance testing at the supplier's site (the alpha test) and immediately before the general release of the software as a product.[5]

Feature-complete

[edit]A feature-complete (FC) version of a piece of software has all of its planned or primary features implemented but is not yet final due to bugs, performance or stability issues.[6] This occurs at the end of alpha testing in development.

Usually, feature-complete software still has to undergo beta testing and bug fixing, as well as performance or stability enhancement before it can go to release candidate, and finally gold status.

Beta

[edit]Beta, named after the second letter of the Greek alphabet, is the software development phase following alpha. A beta phase generally begins when the software is feature-complete but likely to contain several known or unknown bugs.[7] Software in the beta phase will generally have many more bugs in it than completed software and speed or performance issues, and may still cause crashes or data loss. The focus of beta testing is reducing impacts on users, often incorporating usability testing. The process of delivering a beta version to the users is called beta release and is typically the first time that the software is available outside of the organization that developed it. Software beta releases can be either open or closed, depending on whether they are openly available or only available to a limited audience. Beta version software is often useful for demonstrations and previews within an organization and to prospective customers. Some developers refer to this stage as a preview, preview release, prototype, technical preview or technology preview (TP),[8] or early access.

Beta testers are people who actively report issues with beta software. They are usually customers or representatives of prospective customers of the organization that develops the software. Beta testers tend to volunteer their services free of charge but often receive versions of the product they test, discounts on the release version, or other incentives.[9][10]

Perpetual beta

[edit]Some software is kept in so-called perpetual beta, where new features are continually added to the software without establishing a final "stable" release. As the Internet has facilitated the rapid and inexpensive distribution of software, companies have begun to take a looser approach to the use of the word beta.[11]

Open and closed beta

[edit]Developers may release either a closed beta, or an open beta; closed beta versions are released to a restricted group of individuals for a user test by invitation, while open beta testers are from a larger group, or anyone interested. Private beta could be suitable for the software that is capable of delivering value but is not ready to be used by everyone either due to scaling issues, lack of documentation or still missing vital features. The testers report any bugs that they find, and sometimes suggest additional features they think should be available in the final version.

Open betas serve the dual purpose of demonstrating a product to potential consumers, and testing among a wide user base is likely to bring to light obscure errors that a much smaller testing team might not find.[citation needed]

Release candidate

[edit]

A release candidate (RC), also known as gamma testing or "going silver", is a beta version with the potential to be a stable product, which is ready to release unless significant bugs emerge. In this stage of product stabilization, all product features have been designed, coded, and tested through one or more beta cycles with no known showstopper-class bugs. A release is called code complete when the development team agrees that no entirely new source code will be added to this release. There could still be source code changes to fix defects, changes to documentation and data files, and peripheral code for test cases or utilities.[citation needed]

Stable release

[edit]Also called production release, the stable release is the last release candidate (RC) which has passed all stages of verification and tests. Any known remaining bugs are considered acceptable. This release goes to production.

Some software products (e.g. Linux distributions like Debian) also have long-term support (LTS) releases which are based on full releases that have already been tried and tested and receive only security updates.[citation needed]

Release

[edit]Once released, the software is generally known as a "stable release". The formal term often depends on the method of release: physical media, online release, or a web application.[12]

Usually the released software is assigned an official version name or version number. (Pre-release software may or may not have a separate internal project code name or internal version number).

Release to manufacturing (RTM)

[edit]

The term "release to manufacturing" (RTM), also known as "going gold", is a term used when a software product is ready to be delivered. This build may be digitally signed, allowing the end user to verify the integrity and authenticity of the software purchase. The RTM build is known as the "gold master" or GM[13] is sent for mass duplication or disc replication if applicable. The terminology is taken from the audio record-making industry, specifically the process of mastering. RTM precedes general availability (GA) when the product is released to the public. A golden master build (GM) is typically the final build of a piece of software in the beta stages for developers. Typically, for iOS, it is the final build before a major release, however, there have been a few exceptions.

RTM is typically used in certain retail mass-production software contexts—as opposed to a specialized software production or project in a commercial or government production and distribution—where the software is sold as part of a bundle in a related computer hardware sale and typically where the software and related hardware is ultimately to be available and sold on mass/public basis at retail stores to indicate that the software has met a defined quality level and is ready for mass retail distribution. RTM could also mean in other contexts that the software has been delivered or released to a client or customer for installation or distribution to the related hardware end user computers or machines. The term does not define the delivery mechanism or volume; it only states that the quality is sufficient for mass distribution. The deliverable from the engineering organization is frequently in the form of a golden master media used for duplication or to produce the image for the web.

General availability (GA)

[edit]

General availability (GA) is the marketing stage at which all necessary commercialization activities have been completed and a software product is available for purchase, depending, however, on language, region, and electronic vs. media availability.[14] Commercialization activities could include security and compliance tests, as well as localization and worldwide availability. The time between RTM and GA can take from days to months before a generally available release can be declared, due to the time needed to complete all commercialization activities required by GA. At this stage, the software has "gone live".

Release to the Web (RTW)

[edit]Release to the Web (RTW) or Web release is a means of software delivery that utilizes the Internet for distribution. No physical media are produced in this type of release mechanism by the manufacturer. Web releases have become more common as Internet usage has grown.[citation needed]

Support

[edit]During its supported lifetime, the software is sometimes subjected to service releases, patches or service packs, sometimes also called "interim releases" or "maintenance releases" (MR). For example, Microsoft released three major service packs for the 32-bit editions of Windows XP and two service packs for the 64-bit editions.[15] Such service releases contain a collection of updates, fixes, and enhancements, delivered in the form of a single installable package. They may also implement new features. Some software is released with the expectation of regular support. Classes of software that generally involve protracted support as the norm include anti-virus suites and massively multiplayer online games. Continuing with this Windows XP example, Microsoft did offer paid updates for five more years after the end of extended support. This means that support ended on April 8, 2019.[16]

End-of-life

[edit]When software is no longer sold or supported, the product is said to have reached end-of-life, to be discontinued, retired, deprecated, abandoned, or obsolete, but user loyalty may continue its existence for some time, even long after its platform is obsolete—e.g., the Common Desktop Environment[17] and Sinclair ZX Spectrum.[18]

After the end-of-life date, the developer will usually not implement any new features, fix existing defects, bugs, or vulnerabilities (whether known before that date or not), or provide any support for the product. If the developer wishes, they may release the source code, so that the platform may be maintained by volunteers.

History

[edit]Usage of the "alpha/beta" test terminology originated at IBM.[citation needed] Similar terminologies for IBM's software development were used by people involved with IBM from at least the 1950s (and probably earlier). "A" test was the verification of a new product before the public announcement. The "B" test was the verification before releasing the product to be manufactured. The "C" test was the final test before the general availability of the product. As software became a significant part of IBM's offerings, the alpha test terminology was used to denote the pre-announcement test and the beta test was used to show product readiness for general availability. Martin Belsky, a manager on some of IBM's earlier software projects claimed to have invented the terminology. IBM dropped the alpha/beta terminology during the 1960s, but by then it had received fairly wide notice. The usage of "beta test" to refer to testing done by customers was not done in IBM. Rather, IBM used the term "field test".

Major public betas developed afterward, with early customers having purchased a "pioneer edition" of the WordVision word processor for the IBM PC for $49.95. In 1984, Stephen Manes wrote that "in a brilliant marketing coup, Bruce and James Program Publishers managed to get people to pay for the privilege of testing the product."[19] In September 2000, a boxed version of Apple's Mac OS X Public Beta operating system was released.[20] Between September 2005 and May 2006, Microsoft released community technology previews (CTPs) for Windows Vista.[21] From 2009 to 2011, Minecraft was in public beta.

In February 2005, ZDNet published an article about the phenomenon of a beta version often staying for years and being used as if it were at the production level.[22] It noted that Gmail and Google News, for example, had been in beta for a long time although widely used; Google News left beta in January 2006, followed by Google Apps (now named Google Workspace), including Gmail, in July 2009.[12] Since the introduction of Windows 8, Microsoft has called pre-release software a preview rather than beta. All pre-release builds released through the Windows Insider Program launched in 2014 are termed "Insider Preview builds". "Beta" may also indicate something more like a release candidate, or as a form of time-limited demo, or marketing technique.[23]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Encyclopedia definition of alpha version". PC Magazine. Archived from the original on 2011-04-27. Retrieved 2011-01-12.

- ^ "What is an alpha version of a game?". Archived from the original on 2022-09-23. Retrieved 2022-09-23.

- ^ Ince, Darrel, ed. (2013). "Alpha software". A Dictionary of the Internet (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-174415-0. Retrieved 2019-07-15.

- ^ "The Next Generation 1996 Lexicon A to Z". Next Generation. No. 15. Imagine Media. March 1996. p. 29.

Alpha software generally barely runs and is missing major features like gameplay and complete levels.

- ^ A Dictionary of Computer Science (7th ed.). Oxford University Press. 2016. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-19-968897-5.

- ^ Cusumano, Michael (1998). Microsoft Secrets: How the World's Most Powerful Software Company Creates Technology, Shapes Markets, and Manages People. Free Press. pp. 202–203. ISBN 978-0-684-85531-8.

- ^ "The Next Generation 1996 Lexicon A to Z". Next Generation. No. 15. Imagine Media. March 1996. p. 30.

- ^ "Technology Preview Features Support Scope". Red Hat. Retrieved 2015-03-18.

- ^ Amit Mehra; Rajib Lochan Saha (2017-06-19). "Utilizing Public Betas and Free Trials to Launch a Software Product". Production and Operations Management. Vol. 27, no. 11.

- ^ Lang, Michelle M. (2004-05-17). "Beta Wars". Design News. Vol. 59, no. 7.

- ^ "Waiting with Beta'd Breath TidBITS #328 (May 13, 1996)". 1996-05-13. Archived from the original on 2022-12-06.

- ^ a b "Google Apps is out of beta (yes, really)". Google Blog. 2009-07-07. Archived from the original on 2011-01-21. Retrieved 2011-01-12.

- ^ "What is Golden Master (GM)? - Definition from Techopedia". Techopedia.com. 2013-08-19.

- ^ Luxembourg, Yvan Philippe (2013-05-20). "Top 200 SAM Terms – A Glossary Of Software Asset Management Terms". Operations Management Technology Consulting. Archived from the original on 2013-08-10. Retrieved 2013-05-21.

- ^ "Microsoft Update Catalog". www.catalog.update.microsoft.com. Retrieved 2024-05-03.

- ^ "Microsoft Product Lifecycle Search". 2012-07-20. Archived from the original on 2012-07-20. Retrieved 2024-05-03.

- ^ "[cdesktopenv-devel] CDE 2.2.1 released | CDE - Common Desktop Environment". sourceforge.net. Retrieved 2024-05-03.

- ^ "ZX-Uno [ZX Spectrum Computer Clone Based on FPGA]". 2018-01-05. Archived from the original on 2018-01-05. Retrieved 2024-05-03.

- ^ Manes, Stephen (1984-04-03). "Taking A Gamble With Word Vision". PC Magazine - The Independent Guide To IBM Personal Computers. Vol. 3, no. 6. PC Communications Corp. pp. 211–221. ISSN 0745-2500. Archived from the original on 2015-03-17. Retrieved 2015-02-15.

- ^ "Apple Releases Mac OS X Public Beta" (Press release). Apple Inc. 2000-09-13. Retrieved 2024-01-28.

- ^ "Microsoft Windows Vista October Community Technology Preview Fact Sheet" (Press release). Microsoft. October 2005. Archived from the original on 2011-04-30. Retrieved 2011-02-22.

- ^ Festa, Paul (2005-02-11). "A long winding road out of beta". ZDNet. Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ Houghton, David (2010-05-17). "The inconvenient truths behind betas". GamesRadar. Archived from the original on 2011-04-30.