Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Operation Courageous

View on Wikipedia| Operation Courageous | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Korean War | |||||||

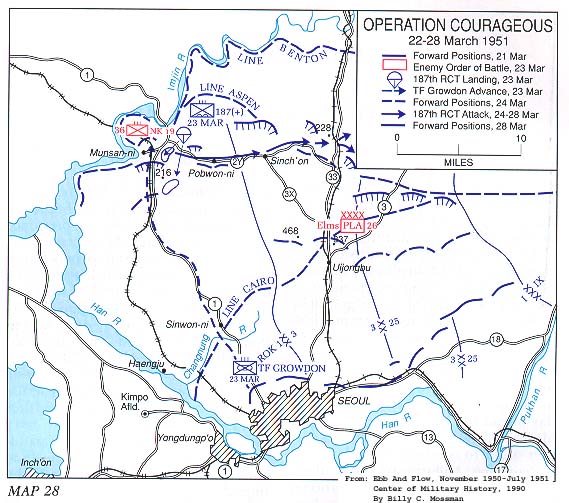

Map of the operation. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Douglas MacArthur Matthew Ridgway Frank S. Bowen | Unknown | ||||||

Operation Courageous was a military operation performed by the United Nations Command (UN) during the Korean War designed to trap large numbers of Chinese People's Volunteer Army (PVA) and Korean People's Army (KPA) troops between the Han and Imjin Rivers north of Seoul, opposite the Republic of Korea Army (ROK) I Corps. The intent of Operation Courageous was for US I Corps, which was composed of the US 25th and 3rd Infantry Divisions and the ROK 1st Infantry Division, to advance quickly on the PVA/KPA forces and reach the Imjin River with all possible speed.

Maneuvering

[edit]As Operation Ripper showed that the PVA/KPA forces were withdrawing north of Seoul, US Eighth Army commander General Matthew Ridgway planned to block and attack the retreat of KPA I Corps. On 21 March Ridgway ordered US I Corps to move forward to the Cairo Line, which he extended southwestward across General Frank W. Milburn's zone through Uijongbu (37°43′40″N 127°3′3″E / 37.72778°N 127.05083°E) to the vicinity of Haengju (37°37′49″N 126°46′11″E / 37.63028°N 126.76972°E) on the Han River. At points generally along this line 6–10 miles (9.7–16.1 km) to the north, Milburn's patrols had made some contact with KPA I Corps west of Uijongbu and the PVA 26th Army to the east. Milburn was to occupy the Cairo Line on 22 March, a day ahead of the airborne landing at Munsan-ni, and wait for Ridgway's further order to continue north.[1]

Requiring Milburn to wait stemmed from Ridgway's not yet having given the final green light to the airborne landing, Operation Tomahawk, as of 21 March. Operation Tomahawk would take place only if Ridgway received assurances that weather conditions on 23 March would favor a parachute drop, and that ground troops could link up with the airborne force within twenty-four hours. If these assurances were forthcoming, the 187th Airborne Regimental Combat Team (187th RCT), with the 2nd and 4th Ranger Companies attached, was to drop in the Munsan-ni area on the morning of 23 March and block Route 1. Milburn was to establish physical contact with and assume control of the airborne force once it was on the ground. At the same time, he was to open a general Corps' advance toward the Aspen Line, which traced the lower bank of the Imjin River west and north of Munsan-ni, then sloped eastward across the corps zone to cut Routes 33 and 3 8 miles (13 km) north of Uijongbu. Once on Aspen, Milburn was to expect Ridgway's order to continue to the Benton Line, the final Courageous objective line, some 10 miles (16 km) farther north. Reaching Benton would carry I Corps virtually to the 38th Parallel except in the west where the final line fell off to the southwest along the Imjin.[2]

Because I Corps otherwise would have an open east flank when it moved to the Benton Line, Ridgway extended its line southeastward into the US IX Corps' zone, across the front of the 24th Division and about halfway across the front of the ROK 6th Infantry Division to a juncture with the Cairo Line. When Ridgway ordered I Corps to Benton, General William M. Hoge was to send his western forces to the line to protect the I Corps' flank. Meanwhile, in concert with Milburn's drive to the Cairo and Aspen Lines, General Hoge was to complete the occupation of his sector of the Cairo Line. Elsewhere along the army front, US X Corps and the ROK III and I Corps remained under Ridgway's order of 18 March to reconnoiter the area between the Hwach'on Reservoir and the east coast. As yet, neither General Edward Almond's patrols nor those of the ROK corps had moved that deeply into North Korean territory.[3]

The three divisions of I Corps started towards the Cairo Line at 08:00 on 22 March. The ROK 1st Infantry Division, advancing astride Route 1 in the west, overcame very light resistance and had troops on the phase line by noon. The ROK 3rd Infantry Division astride Route 3 in the center and the US 25th Infantry Division on the right also met sporadic opposition, but moved slowly and ended the day considerably short of the line.[4]

Meanwhile, Milburn assembled an armored task force in Seoul for a drive up Route 1 to make the initial contact with the 187th RCT, if and after it dropped on Munsan-ni. Building the force around the 6th Medium Tank Battalion, which was borrowed from the 24th Infantry Division of IX Corps, he added the 2nd Battalion, 7th Infantry Regiment; all but one battery of the 58th Armored Field Artillery Battalion from the 3rd Division; and from Corps' troops he supplied a battery of the 999th Armored Field Artillery Battalion and Company A, 14th Engineer Combat Battalion. He also included two bridgelaying Churchill tanks from the British 29th Brigade, which had recently been attached to I Corps. Lt. Col. John S. Growdon, commander of the 6th Medium Tank Battalion, was to lead the task force.[5]

Ridgway made the final decision on the airborne operation late in the afternoon of 22 March during a conference at Eighth Army main headquarters in Taegu. General Earle E. Partridge, the Fifth Air Force commander, assured him that the weather would be satisfactory on the next day; Colonel Gilman C. Mudgett, the new Eighth Army G-3 operations officer, predicted that contact with the airborne unit would be made within a day's time, as Ridgway required, and also that the entire I Corps should be able to advance rapidly.[6] Given these reports, Ridgway ordered the airborne landing to take place at 09:00 on the following day.[7]

On hearing the final word on the Munsan-ni drop, Milburn directed Task Force Growdon to pass through the ROK 1st Division on the Cairo Line early on 23 March and proceed via Route 1 to reach the airborne troops, while his three divisions were to resume their advance with the objective of reaching the Aspen Line. The ROK 1st Division, which would be following Task Force Growdon, was to relieve the 187th RCT upon reaching Munsan-ni, and the airborne unit then was to prepare to move south and revert to Eighth Army reserve.[8]

First attack

[edit]

On 23 March, Task Force Growdon, which was completely motorized, passed through the ROK 1st Division shortly after 07:00. No PVA/KPA forces opposed the armored column as it moved ahead of the ROK, but within minutes the third tank in column hit a mine while bypassing a destroyed bridge at the small Changneung River. The task force was held up while engineers removed a dozen other mines from the bypass. Proceeding slowly from that point with a mine detector team leading the way afoot, Growdon's column moved only 1 mile (1.6 km) to the village of Sinwon-ni before encountering more mines. When the 187th RCT began landing at Munsan-ni at 09:00, Growdon's task force was stopped some 15 miles (24 km) to the south.[9]

C-46 Commandos and C-119 Flying Boxcars of the 315th Air Division had begun lifting the airborne troops from the Taegu airfield shortly after 07:00, all heading initially for a rendezvous point over the Yellow Sea west of the objective area.[10] The second serial of aircraft, with the 1st Battalion, 187th RCT aboard, was in flight only briefly before engine trouble in the lead plane forced the pilot to return to Taegu for a replacement aircraft. The combat team landed before the new lead plane, whose passengers included the 1st Battalion commander, could reach Munsan-ni. The drop, as a result, did not come off entirely as planned.[11]

General Frank S. Bowen, commander of the 187th RCT, had designated two drop zones, one about 1 mile (1.6 km) northeast of Munsan-ni at 37°51′36″N 126°48′16″E / 37.86000°N 126.80444°E, another about 3 miles (4.8 km) southeast of town at 37°49′32″N 126°49′14″E / 37.82556°N 126.82056°E. The 1st Battalion was to land in the lower zone, the remainder in the one to the north. As planned, the 3rd Battalion with the 4th Ranger Company attached jumped first, Bowen having given it the mission of securing the northern drop zone. Bowen's plan went awry when the leaderless second serial of planes mistakenly followed the first and dropped the 1st Battalion also in the northern zone. The 2nd Battalion with the 2nd Ranger Company followed not long after, then the 674th Airborne Field Artillery Battalion, and at 10:00 the artillery heavy drop.[12]

In the brief interval between the drops of the 1st and 2nd Battalions, Ridgway arrived by L-19, landing on a road between Munsan-ni and the northern drop zone.[13] En route, he had flown over Task Force Growdon then held up at Sinwon-ni, a fact he passed to Bowen. Shortly after 10:00, Ridgway saw a single stick of paratroops jump from a plane over the lower drop zone. The replacement plane carrying the 1st Battalion commander and party had finally reached Munsan-ni, and its passengers had jumped in the correct zone not knowing that they would be the only troops in the area.[14]

To the north, resistance in and immediately around the drop zone was minor and sporadic, amounting to a few small groups of KPA and a meager amount of fire from mortars located somewhere to the north. Overcrowding caused by the 1st Battalion's misdirected drop complicated the 3rd Battalion's assembly, but units managed to sort themselves out and secure the borders of the drop zone. An unexpected annoyance was created by civilians who appeared in the drop zone and began carrying away parachutes. Shots fired over their heads ended the attempted theft. Against moderate but scattered opposition the 2nd Battalion proceeded to occupy heights northeast of the drop zone, and under the command of its executive officer the 1st Battalion, less Company B, moved into the ground to the north and northwest, clearing Munsan-ni itself in the process.[15]

Company B went on a rescue mission to the southern drop zone after learning that the command group of the 1st Battalion had come under fire on Hill 216 (37°50′18″N 126°48′27″E / 37.83833°N 126.80750°E) overlooking the drop zone from the northwest. Company B forced the PVA troops off the hill, allowing its survivors to withdraw to the southwest, and reached the drop zone by 15:00. The rescue force and the battalion command group arrived at the regimental position to the north about two hours later. By that time Bowen's forces had secured all assigned objectives.[16]

Battle casualties among the airborne troops were light, totalling 19. Jump casualties were higher at 84, but almost half of these returned to duty immediately after treatment.[17]

PVA/KPA casualties included 136 dead counted on the field and 149 taken captive. Estimated losses raised the total considerably higher. Prisoner interrogation indicated that the forces who had been in the objective area were from the KPA 36th Regiment, 19th Division and had numbered between three hundred and five hundred. Most of the remainder of the KPA I Corps apparently had withdrawn above the Imjin well before the airborne landing.[18]

Linkup

[edit]The point of Task Force Growdon reached Munsan-ni at 18:30 on 23 March, but the remainder of the extended column took several hours longer. The force encountered no PVA/KPA positions along Route 1 but was kept to an intermittent crawl by having to lift or explode over 150 live mines, some of them booby-trapped, and almost as many dummy mines, including a 5 miles (8.0 km) stretch of buried C-rations and beer cans. Casualties were few, but four tanks were disabled by mines. As the last of these tanks hit a mine 1 mile (1.6 km) below Munsan-ni, the explosion attracted artillery fire that damaged two more. The tail of the task force finally arrived at the airborne position at 07:00 on 24 March.[19]

Milburn's orders to the 187th RCT for operations on 24 March called only for patrolling. Having been given control of Task Force Growdon by Milburn, Bowen built his principal patrols around Task Force Growdon's tanks and sent them to investigate ferry sites on the Imjin and to check Route 2Y, an earthen road running east from Munsan-ni, as far as the village of Sinch'ŏn, 10 miles (16 km) away. One patrol made contact while checking an Imjin ferry site and ford 10 miles (16 km) northeast of Munsan-ni. Six PVA were killed and twenty-two captured. The patrol suffered no casualties, but a tank had to be destroyed after it got bogged down at a stream crossing while approaching the lmjin[check spelling]. A few rounds of artillery fire meanwhile fell in the northern drop zone but caused no casualties.[20]

The ROK 1st Division had advanced steadily toward Munsan-ni without enemy contact. Early on 24 March, Task Force Boone, a division armored column consisting of Company C, 64th Tank Battalion (on loan to General Paik Sun-yup from the 3rd Division), Paik's tank destroyer battalion (organized as an infantry unit), and two of his engineer platoons, stepped ahead of the division and reached the 187th RCT at midmorning. By day's end the remainder of the division occupied a line extending from positions along Route 1 about 3 miles (4.8 km) below Munsan-ni northeastward to Pobwon-ni, a village on lateral Route 2Y 6 miles (9.7 km) east of Munsan-ni area. Paik relieved Bowen of responsibility for the Munsan-ni area at 17:00 and placed Task Force Boone in position just above the town.[21]

The lack of resistance to the wider sweep of the ROK 1st Division's advance confirmed that the bid to block and attack the KPA I Corps had been futile. To the east, the fact that the PVA 26th Army still had forces deployed to delay the advance of the 3rd and 25th Divisions had become equally clear. On I Corps' right, the 25th Division had run into a large number of minefields and small but well-entrenched PVA groups employing small arms, machine gun, and mortar fire. At nightfall on March 24 General Joseph F. Bradley's forces held positions almost due west of Uijongbu in the 3rd Division's zone at corps center.[22]

Chinese defense and retreat

[edit]

Somewhat unexpectedly, the 3rd Division had come up against unusually strong PVA positions. On March 23 General Robert H. Soule's forces had occupied the Uijongbu area with little difficulty. First to enter the town was Task Force Hawkins, built around the bulk of the 64th Tank Battalion and two platoons of tanks from each of the 15th and 65th Infantry Regiments. Reaching Uijongbu about 09:00 and finding it undefended, the task force reconnoitered north several miles on Route 33 before returning to the division position. Mines disabled two tanks, but otherwise the task force made no contact.[23]

Though it thus appeared that the 3rd Division could continue to move forward with relative ease, Soule's forces came under heavy fire when they resumed their attack on the morning of 24 March. The PVA had organized strong positions in Hill 468 (37°45′45″N 127°0′7″E / 37.76250°N 127.00194°E) rising 3 miles (4.8 km) northwest of Uijongbu and Hill 337 (37°45′51″N 127°3′57″E / 37.76417°N 127.06583°E) about 1 mile (1.6 km) north and slightly east of town. From these positions they were in fair condition to block advance on the Route 33 axis to the north and over Route 3 leading out of Uijongbu to the northeast. On the division's right, the 15th Infantry eventually managed to clear Hill 337 on the 24th, but the 65th Infantry on the left failed in an all-day attempt to force the PVA from the Hill 468.[24]

Milburn viewed the situation at Corps' center as an opportunity to trap and destroy the PVA holding up the 3rd Division. After Soule's forces encountered the strong PVA positions on the morning of 24 March, he ordered Bowen to pull in his patrols and prepare the 187th RCT for an eastward attack on the Route 2Y axis. The objective was high ground abutting Route 33 about 10 miles (16 km) north of Uijongbu, thus just above the trace of the Aspen Line, whence Bowen was to prevent the PVA in front of the 3rd Division from withdrawing over Route 33. The 3rd Division was to continue its northward attack in the meantime and eventually drive the PVA against Bowen's position.[25]

Bowen started east at 18:00, intending to march as far as Sinch'on during the night and open his attack the following morning. From Task Force Growdon, Company C was the only unit of the 6th Tank Battalion able to move at 18:00; all other companies of the battalion had too little fuel after patrolling and were to catch up with Bowen's column after being resupplied from Seoul. Task Force Growdon now also was short the 2nd Battalion, 7th Infantry, which had been sent back to the 3rd Division.[26]

A force shaped around the tanks of Company C led the way toward Sinch'on. But after 7 miles (11 km), as Bowen's column moved through a system of ridges, landslides twice trapped the leading tanks, and in the second instance no bypass could be found. As engineers tried to open the road, rain began to fall and became steadily heavier. With the rain making a poor road even worse, Bowen ordered the tanks back to Munsan-ni. After the engineers had cleared the road sufficiently, his remaining forces proceeded to Sinch'on, arriving about 06:00 on 25 March.[27]

A half-hour later Bowen ordered the 2nd Battalion, with the 3rd Battalion following in support, to seize Hill 228 (37°55′4″N 127°2′50″E / 37.91778°N 127.04722°E) rising on the west side of Route 33. Running into small arms, machine gun, and mortar fire from positions on several nearer hills and hampered by a continuing driving rain, the two battalions at day's end were some 2 miles (3.2 km) short of Hill 228, and Route 33 remained available to the PVA in front of the 3rd Division if they chose to withdraw over it.[28]

Withdrawal seemed to be the Chinese intention. The 3rd Division met only light resistance when it resumed its attack from the south on March 25 and advanced 2 miles (3.2 km) beyond the hills where strong PVA positions had delayed it the day before. The tank company of the 65th Infantry meanwhile moved ahead on Route 3X, a secondary road angling northwest off Route 33 to Sinch'on, in an attempt to contact the 187th RCT. Mines along the road disabled four tanks and kept the company from reaching its destination, but it encountered no enemy positions. The withdrawal of the PVA delaying forces was confirmed on 26 March when the 3rd Division and the 25th Division as well moved forward against little or no opposition.[29]

To the north, the PVA continued to oppose the efforts of the 187th RCT to capture Hill 228. Using Route 33 and a lesser road to the west, two tank columns from the 3rd Division joined Bowen's forces during the afternoon of 26 March, but, even with armored support, it was 09:00 the following day before the 187th captured Hill 228.[30] Using the remainder of March 27 for reorganization and resupply, Bowen attacked the heights on the east side of Route 33 early on 28 March and occupied them after an all-day battle to eliminate stiff resistance.[31]

The 15th and 65th Infantry Regiments of the 3rd Division meanwhile reached the airborne forces, the 1st Battalion, 15th Infantry making first contact late in the afternoon of 27 March. Despite Milburn's hopes for the operation, the two regiments drove no PVA/KPA into the guns of the airborne unit. Either the PVA resisting the eastward attack of the 187th RCT had kept Route 33 open long enough for the forces withdrawing before the 3rd Division to pass north, or the withdrawing PVA units had used another road, perhaps Route 3. Moving through spotty resistance, the 25th Division on the right had kept pace with the 3rd Division, and by nightfall on 28 March both were on or above line Aspen.[32]

Operation Ripper Linkup

[edit]Late on 26 March, as it became obvious that the PVA were backing away from the 3rd and 25th Divisions, Ridgway had ordered I and IX Corps to continue to the Benton Line. As originally conceived, the IX Corps' advance to Benton was limited to Hoge's western forces and was intended simply to protect I Corps' right flank. But Ridgway had since modified his plan of operations, widening the advance to include the entire IX Corps and all other forces to the east.[33]

On 23 March, he had lengthened the Benton Line eastward through the 1st Cavalry Division's patrol base at Ch'unch'on and as far as the 1st Marine Division's zone on IX Corps' right, where it joined the last few miles of the Cairo Line. On the following day he had extended the Cairo Line from its original terminus in the Marine zone northeastward across the remainder of the army front to the town of Chosan-ni on the east coast.[34] The final objective line of Operation Ripper thus had become a combination of the Benton and Cairo Lines, following the upstream trace of the Imjin virtually to the 38th Parallel in the west, a few miles below the parallel for almost all of its remaining length to the east, then rising to an east coast anchor some 8 miles (13 km) above the parallel.

Ridgway's forces achieved the adjusted line by the end of March, encountering no more than the sporadic delaying action that had characterized the opposition to Operation Ripper from the outset. Thus, since 7 March Eighth Army forces had made impressive territorial gains, recapturing the South Korean capital and moving between 25–30 miles (40–48 km) north to reach the 38th Parallel. Estimates of PVA/KPA killed and wounded during the month were high, and some 4,800 PVA/KPA had been captured. Nevertheless, the results in terms of troops and supplies destroyed were considerably less than anticipated. The clear fact was that the PVA/KPA high command had been and still was marshalling its main forces beyond the reach of Operation Ripper. Equally obvious was that only advances above the 38th Parallel could attack these main forces.[35]

38th Parallel

[edit]As Ridgway was about to open Operation Courageous, the gains he already had registered in his Killer and Ripper advances had influenced a decision in Washington by which operations above the 38th Parallel assumed new importance as a political question. The decision centered on how and when to approach the desired cease-fire. Notwithstanding the building evidence of KPA offensive preparations, officials of the Departments of State and Defense believed that Ridgway's recent successes might have convinced the Chinese and North Koreans that they could not win a military victory and, if this was the case, that they might agree to negotiate an end to hostilities. On the advice of these officials, President Harry S. Truman planned to make a public statement suggesting the United Nations' willingness to end the fighting. The statement was carefully worded to avoid a threatening tone and so to encourage a favorable reply. Truman intended to deliver the appeal as soon as his statement had been approved by officials of all nations that had contributed forces to the U.N. Command.[36]

The timing of the presidential announcement was tied also to the fact that Ridgway's forces were fast approaching the 38th Parallel. The consensus in Washington was that the Chinese and North Koreans would be more inclined to agree to a cease-fire under conditions restoring the status quo ante bellum, that is, if the fighting could be ended in the vicinity of the 38th Parallel where it had begun. Therefore, while there was no intention to forbid all ground action above the parallel, there was some question in the mind of Secretary of State Dean Acheson and among many members of the United Nations whether the Eighth Army should make a general advance into North Korea.[37]

The Joint Chiefs of Staff notified General Douglas MacArthur of the President's plan in a message radioed from Washington on March 20. They informed him of the prevalent feeling in the United Nations that the UN Command should make no major advance above the 38th Parallel before the presidential appeal was delivered and the reactions to it determined. They also asked for his recommendations on how much freedom of ground action UN forces should have in the vicinity of the parallel during the diplomatic effort to provide for their security and to allow them to maintain contact with the PVA/KPA.[38]

MacArthur had been pressing Washington for decisions favoring a military, not a diplomatic, solution to the war. Shortly before he received the Joint Chiefs' message he again had expressed his views in a letter to Republican Congressman Joseph William Martin Jr. of Massachusetts, the-minority leader in the United States House of Representatives.[39] The congressman earlier had written MacArthur asking for comment on Martin's thesis that Nationalist Chinese forces "might be employed in the opening of a second Asiatic front to relieve the pressure on our forces in Korea." MacArthur replied that his own view followed "the conventional pattern of meeting force with maximum counterforce", that Martin's suggestion on the use of Chiang Kai-shek's forces was in consonance with this pattern, and that there was "no substitute for victory".[40]

Although he had been denied the decisions that in his judgment favored a military solution, MacArthur nevertheless wanted no further restrictions placed on the operations of his command. In so advising the Joint Chiefs on 21 March, he pointed out, as he had some time earlier, that under current conditions any appreciable UN effort to clear North Korea already was out of the question.[41]

While awaiting a response, MacArthur informed Ridgway of the new development on 22 March. Although MacArthur expected that the response from Washington would be a new directive for ground operations, possibly one forbidding an entry into North Korea in strength, he intended in the meantime to allow the Eighth Army to advance north of the parallel as far as logistics could support major operations. Ridgway otherwise was to be restricted only by having to obtain MacArthur's specific authorization before moving above the parallel in force.[42]

In acknowledging these conditions Ridgway notified MacArthur that he currently was developing plans for an advance that would carry Eighth Army forces 10–20 miles (16–32 km) above the 38th Parallel to a general line following the upstream trace of the Yesong River as far as Sibyon-ni (38°18′32″N 126°41′42″E / 38.309°N 126.695°E) in the west, falling off gently southeastward to the Hwach'on Reservoir, then running east to the coast. As in past and current operations, the objective would be the destruction of enemy troops and materiel. MacArthur approved Ridgway's concept but also scheduled a visit to Korea for 24 March, when he would have an opportunity to discuss the plans in more detail.[43]

Before leaving Tokyo, MacArthur issued a communique in which he offered to confer with his enemy counterpart on arranging a cease-fire. He specified that he was making the offer "within the area of my authority as the military commander" and that he would be in search of "any military means" for achieving the desired result. He thus kept the bid within the military sphere.[44] But in leading up to his offer MacArthur belittled China's military power, noting in particular that Chinese forces could not win in Korea, and made statements that could be, and were, interpreted as threatening that the United Nations would decide to attack China if hostilities continued. These remarks prompted other governments to ask about a possible shift in US policy, and in Truman's judgment they so contradicted the tone of his own planned statement that he decided not to issue it for fear of creating more international confusion.[45]

MacArthur's call for victory in Korea thoroughly angered the President. It was, he wrote a few days later, "not just a public disagreement over policy, but deliberate, premeditated sabotage of US and UN policy."[46] Moreover, MacArthur had not cleared his communique with Washington as the President's directive of December 1950 required for all releases touching on national policy. Truman considered MacArthur's violation of the directive as "open defiance of my orders as President and as Commander in Chief."[47] His immediate act was to order the Joint Chiefs of Staff to send MacArthur a reminder of the December directive. Privately, he decided that MacArthur should be relieved.[48]

Included in the reminder sent by the Joint Chiefs on 24 March (received in Tokyo on 25 March) were orders that MacArthur report to them for instructions should his counterpart respond to his offer and "request an armistice in the field." No such response was expected, however, and since Truman had canceled his own cease-fire initiative, operations in strength above the 38th Parallel again had become a tactical question for MacArthur and Ridgway to answer. MacArthur, in fact, publicly revealed his answer before he really knew that the diplomatic effort to achieve a cease-fire had been canceled. Upon his return to Tokyo late on 24 March following his conference with Ridgway and a visit to the front, he announced that he had directed the Eighth Army to cross the parallel "if and when its security makes it tactically advisable.[49] More specifically than that, of course, MacArthur had approved Ridgway's concept of a general advance as deep as 20 miles (32 km) into North Korea.

Aftermath

[edit]In advance of issuing orders for attacks above the 38th Parallel, Ridgway assembled corps and division commanders at his Yoju headquarters on March 27 to discuss courses of action that were now open to them or that they might be obliged to follow. The possibility of Soviet intervention again had been raised, he told them. According to a reputable foreign source, the Soviets planned to launch a large scale offensive in Korea near the end of April employing Soviet regulars of Mongolian extraction under the guise of volunteers. Ridgway doubted the accuracy of the report, but as a matter of prudence, since the Eighth Army might be ordered out of Korea in the event of Soviet intervention, he intended to pass the evacuation plan outlined by the Eighth Army staff in January to Corps' commanders for further development. Lest Eighth Army forces start "looking over the shoulder", no word of the course of action or preparations for it was to go beyond those working on the plan.[50]

Alluding to past and recent proposals of cease-fire negotiations, Ridgway also advised that future governmental decisions might compel the Eighth Army to adopt a static defense. Because of its inherent rigidity, such a stance would require strong leadership and imaginative tactical thinking, he warned, to stand off a numerically stronger enemy that might not be similarly inhibited in the choice of tactics.

The Eighth Army meanwhile would continue to move forward and in the next advance would cross the 38th Parallel. Ridgway agreed with MacArthur's earlier prediction that a stalemate ultimately would develop on the battlefront, but just how far the Eighth Army would drive into North Korea before this occurred, he informed the assembled commanders, could not be accurately assessed at the moment.[51]

Ridgway had revised his concept for advancing above the parallel since meeting with MacArthur on March 24. He originally had intended to direct a strong attack northwestward across the Imjin, expecting that in moving as far as the Yesong River the attack force would find the elusive KPA I Corps. His intelligence staff later discovered that the bulk of the Corps had withdrawn behind the Yesong and also warned that the attack force would be vulnerable to envelopment by a fresh PVA unit located off the right flank of the advance. (The unit was the XIX Army Group, which intelligence had not yet fully identified.) Ridgway, as a result, elected to limit operations northwest of the Imjin to reconnaissance and combat patrols.[52]

He planned to point his main attack toward the centrally located road and rail complex marked out by the towns of Pyonggang in the north and Ch'orwon and Gimhwa-eup in the south. This complex, eventually named the Iron Triangle by newsmen searching for a dramatic term, lay 20–30 miles (32–48 km) above the 38th Parallel in the diagonal corridor dividing the Taebaek Mountains into northern and southern ranges and containing the major road and rail links between the port of Wonsan in the northeast and Seoul in the southwest. Other routes emanating from the triangle of towns connected with Pyongyang to the northwest and with the western and eastern halves of the present front. A unique center of communications, the complex was of obvious importance to the ability of the communist high command to move troops and supplies within the forward areas and to coordinate operations laterally.

Ridgway's first concern was to occupy ground that could serve as a base both for continuing the advance toward the complex and, in view of the enemy's evident offensive preparations, for developing a defensive position. The base selected, the Kansas Line, traced the lower bank of the Imjin in the west. From the Imjin eastward as far as the Hwach'on Reservoir the line lay 2–6 miles (3.2–9.7 km) above the 38th Parallel across the approaches to the Iron Triangle. Following the lower shoreline of the reservoir, it then turned slightly north to a depth of 10 miles (16 km) above the parallel before falling off southeastward to the Yangyang area on the coast. In the advance to the Kansas Line, designated Operation Rugged, I and IX Corps were to seize the segment of the line between the Imjin and the western edge of the Hwach'on Reservoir. To the east, X Corps was to occupy the portion tracing the reservoir shore and reaching Route 24 in the Soyang River valley, and ROK III and I Corps were to take the section between Route 24 and Yangyang.[53]

In anticipation of enemy offensive operations, Ridgway planned to pull substantial forces off the line immediately after reaching the Kansas Line and prepare them for counterattacks. IX Corps was to release the 1st Cavalry Division. The division was to assemble at Kyongan-ni, below the Han River southeast of Seoul, and prepare to meet PVA/KPA attacks aimed at the capital via Route 1 from the northwest, over Routes 33 and 3 from the north, or through the Pukhan River valley from the northeast. In the X Corps' zone, the bulk of the 2nd Division was to assemble at Hongch'on ready to counter an attack following the Route 29 axis, and a division yet to be selected from one of the two ROK Corps in the east was to assemble at Yuch'on-ni on Route 20 and prepare to operate against PVA/KPA attacks in either Corps sector. The 187th RCT, which on March 29 left the I Corps' zone for Taegu, meanwhile was to be ready to return north to reinforce operations wherever needed.[54]

While these forces established themselves in reserve, Ridgway planned to launch Operation Dauntless, a limited advance toward the Iron Triangle by I and IX Corps. With the objective only of menacing the triangle, not of investing it, the two Corps were to attack in succession to lines Utah and Wyoming. They would create, in effect, a broad salient bulging above the Kansas Line between the Imjin River and Hwach'on Reservoir and reaching prominent heights commanding the Ch'orwon-Kumhwa base of the communications complex. If struck by strong PVA/KPA attacks during or after the advance, the two Corps were to return to the Kansas Line.[55]

To maintain, and in some areas regain, contact with enemy forces, Ridgway allowed each corps to start toward the Kansas Line as it completed preparations. The Operation Rugged advance, as a result, staggered to a full start between 2 and 5 April 2. When MacArthur made his customary appearance on 3 April, this time in the ROK I Corps' zone on the east coast, Ridgway brought him up to date on plans. MacArthur agreed with the Rugged/Dauntless concept, urging in particular that Ridgway make a strong effort to hold the Kansas Line. At the same time, MacArthur believed that the two operations would move the battlefront to that "point of theoretical stalemate" he had predicted in early March. He intended to limit offensive operations, once Ridgway's forces reached their Kansas-Wyoming objectives, to reconnaissance and combat patrols, none larger than a battalion.[56]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Army Center of Military History.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Army Center of Military History.

- ^ Rad, GX-3-3813 KGOO, CG Eighth Army to CG I Corps et al., 21 Mar 51.

- ^ Rads, GX-3-3900 KGOO, GX-3-3908 KGOO, and GX-3-4040 KGOO, CG Eighth Army to CG I Corps et al., first two 21 Mar and last 22 Mar 51; Eighth Army Comd Rpt, Nar, Mar 51; Eighth Army CG SS Rpt, Mar 51.

- ^ Rads, GX-3-3813 KGOO, GX-3-4040 KGOO, and GX-3-4149 KGOO, CG Eighth Army to CG I Corps et al., first one 21 Mar and last two, 22 Mar 51.

- ^ I Corps Opn Dir 50, 21 Mar 51; 1 Corps Comd Rpt, Nar, Mar 51; Eighth Army Comd Rpt, Nar, Mar 51.

- ^ I Corps Opn Dir 51, 22 Mar 51; I Corps Comd Rpt, Nar, Mar 51; Eighth Army Study, Task Force Growdon, in CMH.

- ^ Colonel Mudgett replaced Dabney, who was now a Brigadier General, on 21 March 1951.

- ^ Eighth Army CG SS Rpt, Mar 51; Eighth Army G3 Jul, Sum, 21 Mar 51; Eighth Army Comd Rpt, Nar, Mar 51; Rad, GX-3-4097 KGOO, CG Eighth Army to CG I Corps et al., 22 Mar 51.

- ^ Rad, GX-3-4040 KGOO, CG Eighth Army to CG I Corps et al., 22 Mar 51; Rad, CIACT 3-30, CG I Corps to CO 6th Med Tk Bn, 23 Mar 51; 1 Corps Opn Dir 52, 23 Mar 51

- ^ I Corps Comd Rpt, Nar, Mar 51; Eighth Army Study, Task Force Growdon

- ^ The provisional Combat Cargo Command had been discontinued and the 315th Air Division activated to replace it on 25 January 1951. Brig. Gen. John P. Henebry had replaced General Tunner as commander of the 315th on 8 February 1951.

- ^ Eighth Army Study, Operation Tomahawk, in CMH; 187th Abn RCT Comd Rpt, Nar, Mar 51; Futrell; The United States Air Force in Korea, pp. 353-55.

- ^ Eighth Army Study, Operation Tomahawk, in CMH; 187th Abn RCT Comd Rpt, Nar, Mar 51; Futrell; The United States Air Force in Korea, pp. 353-55.

- ^ Accompanying the 187th RCT to provide additional medical support was a para-surgical team from the Indian 60th Field Ambulance and Surgical Company.

- ^ 187th Abn RCT Opn O 2, 22 Mar 51; 187th Abn RCT Comd Rpt, Nar, Mar 51; Eighth Army Study, Operation Tomahawk.

- ^ 187th Abn RCT Comd Rpt, Nar, Mar 51; Eighth Army CG SS Rpt, Mar 51; Eighth Army Study, Operation Tomahawk.

- ^ 187th Abn RCT Comd Rpt, Nar, Mar 51; Eighth Army Study, Operation Tomahawk; I Corps POR 576, 23 Mar 51.

- ^ Rad, GX (TAC) 124 KCG, CG Eighth Army to CINCFE, 23 Mar 51; Eighth Army Study, Operation Tomahawk.

- ^ Rad, GX (TAC) 124 KCG, CG Eighth Army to CINCFE, 23 Mar 51; Eighth Army Study, Operation Tomahawk.

- ^ I Corps Comd Rpt, Nar, Mar 51; Eighth Army Study, Task Force Growdon.

- ^ I Corps Opn Dir 52, 23 Mar 51; Eighth Army Study, Operation Tomahawk; ibid., Task Force Growdon.

- ^ I Corps POR 576, 23 Mar 51; Eighth Army G3 Consolidated Opn Rpt, 24 Mar 51; Rad, CIACT 3-35, CG I Corps to CG 1st ROK Div, 24 Mar 51; I Corps Comd, Rpt, Nar, Mar 51.

- ^ I Corps Comd Rpt, Nar, Mar 51; 25th Div Comd Rpt, Nar, Mar 51.

- ^ 1 Corps G3 Jnl, 23 Mar 51; 3d Div G3 Jnl, 23 Mar 51; 3d Div Comd Rpt, Nar, Mar 51.

- ^ 3d Div Comd Rpt, Nar, Mar 51.

- ^ Rad, CIACT 3-37, CG I Corps to CG 1st ROK Div et al., 24 Mar 51; 187th Abn RCT S3 Jnl, 24 Mar 51, and Comd Rpt, Nar, Mar 51.

- ^ 187th Abn RCT S3 Jul, 24 Mar 51, and Comd Rpt, Nar, Mar 51; Eighth Army Study, Task Force Growdon.

- ^ 187th Abn RCT Comd Rpt, Nar, Mar 51; Eighth Army Study, Task Force Growdon.

- ^ 187th Alm RCT S3 Jnl, 25 Mar 51; Eighth Army Study, Operation Tomahawk.

- ^ Eighth Army G3 Consol Opn Rpt, 25 Mar 51; I Corps Comd Rpt, Nar, Mar 51; 3d Div Comd Rpt, Nar, Mar 51.

- ^ On the 26th Soule reported to Ridgway that one of his tanks had knocked out a T-34 tank. This was the first enemy armor destroyed by ground action since Ridgway had taken command of the Eighth Army. The T-34 may have belonged to the 17th Mechanized Division of KPA I Corps. See Eighth Army CG SS Rpt, Nar, Mar 51.

- ^ 187th Abn RCT Comd Rpt, Nar, Mar 51; 3d Div Comd Rpt, Nar, Mar 51.

- ^ 3d Div Comd Rpt, Nar, Mar 51; 25th Div Comd Rpt, Nar, Mar 51.

- ^ Rad, GX-3-4877 KGOO, CG Eighth Army to CGs I and IX Corps, 26 Mar 51; Eighth Army Comd Rpt, Nar, Mar 51.

- ^ Rad, GX-3-4228 KGOO, CG Eighth Army to CG I Corps et al., 23 Mar 51; Rad, GX (TAC) 128 KCG, CG Eighth Army to C/S ROKA et al., 24 Mar 51.

- ^ Eighth Army Comd Rpt, Nar, Mar 51; Eighth Army G3 and G2 SS Rpts, Mar 51.

- ^ Collins, War in Peacetime, p. 266; Truman Years of Trial and Hope, p. 440; Acheson, Present at the Creation, pp. 517-18; Schnabel, Policy and Direction, pp. 357-58.

- ^ Collins, War in Peacetime, pp. 263-66; Acheson, Present at the Creation, p. 517; Rees, Korea: The Limited War, p. 208.

- ^ Rad, JCS 86276, JCS to CINCFE, 20 Mar 51.

- ^ The Tokyo dateline of MacArthur's letter was 20 March. Since Tokyo time is fourteen hours ahead of Washington time, MacArthur presumably wrote his letter before the Joint Chiefs prepared their message of the same date.

- ^ Both letters are quoted in MacArthur, Reminiscences, pp. 385-86.

- ^ Rad, C 58203, CINCUNC to DA for JCS, 21 Mar 1951.

- ^ Schnabel, Policy and Direction, pp. 358-60; Rad, C 58292, MacArthur for Ridgway, 22 Mar 1951.

- ^ Rad, G-3-4122 KCG, CG Eighth Army to CINCFE, 22 Mar 51; Rad MacArthur to Ridgway, 23 Mar 51; Eighth Army CG SS Rpt, Mar 51.

- ^ To this extent, MacArthur's action was in accord with earlier advice a Department of State official gave the Department of Defense shortly after the Inchon Landing: "A cease-fire should be a purely military matter and . . . the Commanding General of the unified command . . . is the appropriate representative to negotiate any armistice or cease-fire agreement." See Schnabel, Policy and Direction, p. 359.

- ^ MacArthur, Reminiscences, pp. 387-88; Truman, Years of Trial and Hope, pp. 440-42.

- ^ Ltr, Truman to George M. Elsey, 16 Apr 51, quoted in D. Clayton James, The Years of MacArthur, vol. III, Triumph and Disaster, 1945-1964 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1985), p. 588.

- ^ Truman, Years of Trial and Hope, pp. 441-12.

- ^ Truman, Years of Trial and Hope, pp. 442-43. When asked some years later why he did not relieve MacArthur at the time, Truman replied that he wanted a "better example of his insubordination, and I wanted it to be one . . . that everybody would recognize for exactly what it was, and I knew that, MacArthur being the kind of man he was, I wouldn't have long to wait." See Merle Miller, Plain Speaking (New York: Berkley Publishing Corp., 1973), pp. 302-03.

- ^ Collins, War in Peacetime, pp. 270-71; Ridgway, The Korean War, p. 116; copy of MacArthur's 24 March statement with Ridgway papers in CMH

- ^ Discussion of the conference is based on MS, Ridgway, The Korean War, Issues and Policies, pp. 405, 407-10; Ridgway, The Korean War, pp. 121-23, 157.

- ^ The conference had a tragic postscript when the light plane returning General Kim, commander of ROK I Corps, to Gangneung crashed in the Taebaek Mountains, killing the general and his pilot. General Paik, the leader of the ROK 1st Division, became the new commander of ROK I Corps early in April and Brigadier general Kang Moon Bong took command of the 1st Division.

- ^ Rad, GX-3-5348 KGOP, CG Eighth Army to CG I Corps et al., 29 Mar 51; Ridgway, The Korean War, pp. 120-21; Eighth Army PIR 254, 23 Mar 51, and PIR 259, 28 Mar 51.

- ^ Rad, GX-3-5348 KGOP, CG Eighth Army to CG I Corps et al., 29 Mar 51; Eighth Army G3 Jul, Sum, Apr 51.

- ^ Rad, GX-3-5348 KGOP, CG Eighth Army to CG I Gores et al., 29 Mar 51; Eighth Army G3 Jnl, Sum, 29 Mar 51.

- ^ Rad, GX-4-805 KGOP, CG Eighth Army to CG I Corps et al., 3 Apr 51.

- ^ Eighth Army G3 Jul, Sum, 2 and 3 Apr 51; Rad, GX-4-979 KGOO, CG Eighth Army to C/S ROKA et al., 4 Apr 51; Eighth Army CG SS Rpt, Apr 51; MS, Ridgway, The Korean War, Issues and Policies, pp. 419-20; Ridgway, The Korean War, p. 121; Rad, C 59397, CINCFE to DA, 5 Apr 51.

References

[edit]- Chapter XVIII:Advance to the Parallel in Mossman, Billy C. United States Army in the Korean War: Ebb and Flow November 1950-July 1951Archived 2021-01-29 at the Wayback Machine. (Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History, 1988).