Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Orionids

View on Wikipedia| Orionids (ORI) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Discovery date | October 1839[2] |

| Parent body | 1P/Halley[1] |

| Radiant | |

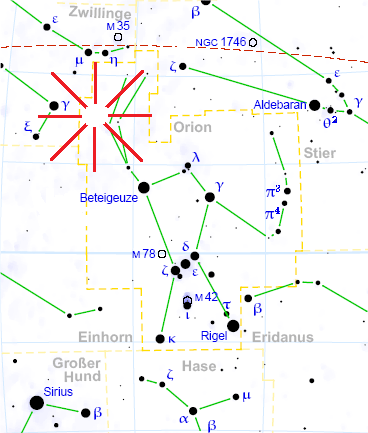

| Constellation | Orion (10 degrees northeast of Betelgeuse)[1] |

| Right ascension | 06h 21m [3] |

| Declination | +15.6°[3] |

| Properties | |

| Occurs during | October 2 – November 7[1] |

| Date of peak | October 21[3] |

| Velocity | 66.9[4] km/s |

| Zenithal hourly rate | 20[5] |

The Orionids meteor shower, often shortened to the Orionids, is one of two meteor showers associated with Halley's Comet (the other one being the Eta Aquariids). The Orionids are named because the point they appear to come from (the radiant) lies in the constellation of Orion. The shower occurs annually, lasting approximately one week in late October. In some years, meteors may occur at rates of 50–70 per hour.[6][7]

Orionid outbursts occurred in 585, 930, 1436, 1439, 1465, and 1623.[8] The Orionids occur at the ascending node of Halley's comet. The ascending node reached its closest distance to Earth around 800 BCE. Currently Earth approaches Halley's orbit at a distance of 0.154 AU (23.0 million km; 14.3 million mi; 60 LD) during the Orionids. The next outburst might be in 2070 as a result of particles trapped in a 2:13 mean-motion resonance with Jupiter.[8]

History

[edit]Meteor showers were connected to comets in the 1800s. E.C. Herrick made an observation in 1839 and 1840 about the activity present in the October night skies. Alexander Herschel produced the first documented record that gave accurate forecasts for the next meteor shower.[9] The Orionids meteor shower is produced by Halley's Comet, which was named after astronomer Edmund Halley and last passed through the inner Solar System in 1986 on its 75–76 year orbit.[10] When the comet passes through the Solar System, the Sun sublimates some of the ice, allowing rock particles to break away from the comet. These particles continue on the comet's trajectory and appear as meteors when they enter Earth's upper atmosphere.

The meteor shower radiant is located in Orion about 10 degrees northeast of Betelgeuse.[1] The Orionids normally peak around October 21–22 and are fast meteors that make atmospheric entry at about 66 km/s (150,000 mph).[3] Halley's comet is also responsible for creating the Eta Aquariids, which occur each May as a result of Earth passing close to the descending node of Halley's comet.[8]

An outburst with a zenithal hourly rate of over 100 occurred on 21 October 2006 as a result of Earth passing through the 1266 BCE, 1198 BCE, and 911 BCE meteoroid streams.[11] In 2015, the meteor shower peaked on October 26.[12]

| Year | Activity Date Range | Peak Date | ZHRmax |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1839 | October 8–15[9] | ||

| 1864 | October 18–20[9] | ||

| 1936 | October 19[11] | ||

| 1981 | October 18–21[9] | October 23 | 20 |

| 1984 | October 21–24[9] | October 21–24 | (flat maximum) |

| 2006 | October 2 — November 7[9][13] | October 21–24[13][14] | 100+[11] |

| 2007 | October 20–24[15] | October 21 (predicted)[15] | 70[16] |

| 2008 | October 15–29[17] | October 20–22 (predicted)[17] | 39 |

| 2009 | October 18–25 [9] | October 22[18] | 45[18] |

| 2010 | October 23 | 38 | |

| 2011 | October 22 | 33 | |

| 2012 | October 2 — November 7 | October 20 and October 23 | 43[19] |

| 2013 | October 22 | ~30[20] | |

| 2014 | October 2 — November 7 | October 21 | 28 |

| 2015 | October 2 — November 7 | October 26 | 37 |

| 2016 | October 2 — November 7 | October 21[21] | 84[12] |

| 2017 | October 21 | 55 | |

| 2018 | October 21 | 58 | |

| 2019 | October 22 | 40 | |

| 2020 | October 22 | 36 | |

| 2021 | October 21 | 41 | |

| 2022 | October 22 | 38 | |

| 2023 | October 21 | 48[12] |

Some Orionid showers have had double peaks, as well as plateaus of activity lasting several days.[9]

Gallery

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Robert Lunsford (2023-10-09). "Viewing the Orionid Meteor Shower in 2023". International Meteor Organization (IMO). Retrieved 2023-10-14. (JPG)

- ^ Jenniskens, Peter (2006), Meteor Showers And Their Parent Comets, Cambridge University Press, p. 9, ISBN 0521853494.

- ^ a b c d "2023 Meteor Shower List". American Meteor Society (AMS). Retrieved 2023-09-10.

- ^ Kero, J.; et al. (October 2011), "First results from the 2009–2010 MU radar head echo observation programme for sporadic and shower meteors: the Orionids 2009", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 416 (4): 2550–2559, Bibcode:2011MNRAS.416.2550K, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.19146.x.

- ^ Rendtel, Jürgen (2008), "The Orionid meteor shower observed over 70 years", in Trigo-Rodríguez, J. M.; Rietmeijer, F. J. M.; Llorca, Jordi; Janches, Diego (eds.), Advances in Meteoroid and Meteor Science, Springer, pp. 106–109, Bibcode:2008amms.book.....T, ISBN 978-0387784182.

- ^ "IMO Meteor Shower Calendar 2009". The International Meteor Organization. 1997–2009. Retrieved 2009-10-22.

- ^ "Orionids Meteor Shower Lights Up the Sky". PhysOrg.com. 2003–2009. Retrieved 2009-10-21.

- ^ a b c Egal, A.; Brown, P. G.; Rendtel, J.; Campbell-Brown, M.; Wiegert, P. (2020). "Activity of the Eta-Aquariid and Orionid meteor showers". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 640 (A58): A58. arXiv:2006.08576. Bibcode:2020A&A...640A..58E. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202038115.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Orionid". Observing the Orionids. Meteor Showers Online. Archived from the original on 2018-07-11. Retrieved 2009-10-21.

- ^ Phillips, Dr. Tony (2009-10-19). "NASA – The 2009 Orionid Meteor Shower". NASA. Archived from the original on 2009-10-22. Retrieved 2009-10-19.

- ^ a b c Sato, Mikiya; Watanabe, Jun-ichi (2007). "Origin of the 2006 Orionid Outburst". Publications of the Astronomical Society of Japan. 59 (4): L21 – L24. doi:10.1093/pasj/59.4.L21.

- ^ a b c MeteorFlux 2.3 (Select Shower: ORI, uncheck "Use temporary database", select year (such as 2016) and click "Create graph")

- ^ a b "October to December 2006". The International Meteor Organization –. 1997–2007. Archived from the original on 2009-11-02. Retrieved 2009-10-22.

- ^ Stone, Wes. "2006 Orionid Meteor Shower Surprise!" (PDF). Sky tour. Retrieved 2009-10-22.

- ^ a b Handwerk, Brian (October 17, 2009). ""Old Faithful" Orionid Meteor Shower Peaks This Weekend". r National Geographic News. Archived from the original on October 19, 2007. Retrieved 2009-10-22.

- ^ Orionids 2007: visual data quicklook. imo.net

- ^ a b "Orionids Meteor Shower 2008 of October". Meteor. October 15, 2008. Retrieved 2009-10-21.

- ^ a b Orionids 2009. imo.net

- ^ Orionids 2012: visual data quicklook. imo.net

- ^ "2013 Orionids Radio results". RMOB. Retrieved 2014-08-13.

- ^ "Look for Orionid meteors this month | Astronomy Essentials". EarthSky. Retrieved 2017-10-16.

External links

[edit]- MeteorFlux 2.1 Realtime Viewer: ORI (International Meteor Organization)

- Orionids Peak This Weekend (Carl Hergenrother : 2012 Oct 20)

- Orionids 2012: visual data quicklook (web archive of International Meteor Organization)

- Spaceweather.com: 2009 Orionid Meteor Shower photo gallery: Page 1

- Orionids at Constellation Guide