Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

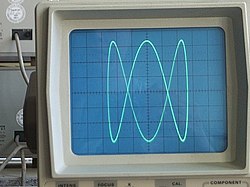

Oscilloscope

View on Wikipedia

An oscilloscope (formerly known as an oscillograph, informally scope or O-scope) is a type of electronic test instrument that graphically displays varying voltages of one or more signals as a function of time. Their main purpose is capturing information on electrical signals for debugging, analysis, or characterization. The displayed waveform can then be analyzed for properties such as amplitude, frequency, rise time, time interval, distortion, and others. Originally, calculation of these values required manually measuring the waveform against the scales built into the screen of the instrument.[1] Modern digital instruments may calculate and display these properties directly.

Oscilloscopes are used in the sciences, engineering, biomedical, automotive and the telecommunications industry. General-purpose instruments are used for maintenance of electronic equipment and laboratory work. Special-purpose oscilloscopes may be used to analyze an automotive ignition system or to display the waveform of the heartbeat as an electrocardiogram, for instance.

History

[edit]Early high-speed visualisations of electrical voltages were made with an electro-mechanical oscillograph,[2][3] invented by André Blondel in 1893. These gave valuable insights into high speed voltage changes, but had a frequency response in single kHz, and were superseded by the oscilloscope which used a cathode-ray tube (CRT) as its display element.

The Braun tube, the first version of the CRT, was known in 1897, and in 1899 Jonathan Zenneck equipped it with beam-forming plates and a magnetic field for deflecting the trace, and this formed the basis of the CRT.[4] Early CRTs had been applied experimentally to laboratory measurements as early as the 1920s, but suffered from poor stability of the vacuum and the cathode emitters. V. K. Zworykin described a permanently sealed, high-vacuum CRT with a thermionic emitter in 1931. This stable and reproducible component allowed General Radio to manufacture an oscilloscope that was usable outside a laboratory setting.[1]

After World War II surplus electronic parts became the basis for the revival of Heathkit Corporation, and a $50 oscilloscope kit made from such parts proved its premiere market success.

Features and uses

[edit]

An analog oscilloscope is typically divided into four sections: the display, vertical controls, horizontal controls and trigger controls. The display is usually a CRT with horizontal and vertical reference lines called the graticule. CRT displays also have controls for focus, intensity, and beam finder.

The vertical section controls the amplitude of the displayed signal. This section has a volts-per-division (Volts/Div) selector knob, an AC/DC/Ground selector switch, and the vertical (primary) input for the instrument. Additionally, this section is typically equipped with the vertical beam position knob.

The horizontal section controls the time base or sweep of the instrument. The primary control is the Seconds-per-Division (Sec/Div) selector switch. Also included is a horizontal input for plotting dual X-Y axis signals. The horizontal beam position knob is generally located in this section.

The trigger section controls the start event of the sweep. The trigger can be set to automatically restart after each sweep or can be configured to respond to an internal or external event. The principal controls of this section are the source and coupling selector switches, and an external trigger input (EXT Input) and level adjustment.

In addition to the basic instrument, most oscilloscopes are supplied with a probe. The probe connects to any input on the instrument and typically has a resistor of ten times the oscilloscope's input impedance. This results in a 0.1 (‑10×) attenuation factor; this helps to isolate the capacitive load presented by the probe cable from the signal being measured. Some probes have a switch allowing the operator to bypass the resistor when appropriate.[1]

Size and portability

[edit]Most modern oscilloscopes are lightweight, portable instruments compact enough for a single person to carry. In addition to portable units, the market offers a number of miniature battery-powered instruments for field service applications. Laboratory grade oscilloscopes, especially older units that use vacuum tubes, are generally bench-top devices or are mounted on dedicated carts. Special-purpose oscilloscopes may be rack-mounted or permanently mounted into a custom instrument housing.

Inputs

[edit]The signal to be measured is fed to one of the input connectors, which is usually a coaxial connector such as a BNC or UHF type. Binding posts or banana plugs may be used for lower frequencies. If the signal source has its own coaxial connector, then a simple coaxial cable is used; otherwise, a specialized cable called a "scope probe", supplied with the oscilloscope, is used. In general, for routine use, an open wire test lead for connecting to the point being observed is not satisfactory, and a probe is generally necessary. General-purpose oscilloscopes usually present an input impedance of 1 megohm in parallel with a small but known capacitance such as 20 picofarads.[5] This allows the use of standard oscilloscope probes.[6] Scopes for use with very high frequencies may have 50 Ω inputs. These must be either connected directly to a 50 Ω signal source or used with Z0 or active probes.

Less-frequently-used inputs include one (or two) for triggering the sweep, horizontal deflection for X‑Y mode displays, and trace brightening/darkening, sometimes called z‑axis inputs.

Probes

[edit]Open wire test leads (flying leads) are likely to pick up interference, so they are not suitable for low level signals. Furthermore, the leads have a high inductance, so they are not suitable for high frequencies. Using a shielded cable (i.e., coaxial cable) is better for low level signals. Coaxial cable also has lower inductance, but it has higher capacitance: a typical 50 ohm cable has about 90 pF per meter. Consequently, a one-meter direct (1×) coaxial probe loads a circuit with a capacitance of about 110 pF and a resistance of 1 megohm.

To minimize loading, attenuator probes (e.g., 10× probes) are used. A typical probe uses a 9 megohm series resistor shunted by a low-value capacitor to make an RC compensated divider with the cable capacitance and scope input. The RC time constants are adjusted to match. For example, the 9 megohm series resistor is shunted by a 12.2 pF capacitor for a time constant of 110 microseconds. The cable capacitance of 90 pF in parallel with the scope input of 20 pF and 1 megohm (total capacitance 110 pF) also gives a time constant of 110 microseconds. In practice, there is an adjustment so the operator can precisely match the low frequency time constant (called compensating the probe). Matching the time constants makes the attenuation independent of frequency. At low frequencies (where the resistance of R is much less than the reactance of C), the circuit looks like a resistive divider; at high frequencies (resistance much greater than reactance), the circuit looks like a capacitive divider.[7]

The result is a frequency compensated probe for modest frequencies. It presents a load of about 10 megohms shunted by 12 pF. Such a probe is an improvement, but does not work well when the time scale shrinks to several cable transit times or less (transit time is typically 5 ns).[clarification needed] In that time frame, the cable looks like its characteristic impedance, and reflections from the transmission line mismatch at the scope input and the probe causes ringing.[8] The modern scope probe uses lossy low capacitance transmission lines and sophisticated frequency shaping networks to make the 10× probe perform well at several hundred megahertz. Consequently, there are other adjustments for completing the compensation.[9][10]

Probes with 10:1 attenuation are by far the most common; for large signals (and slightly-less capacitive loading), 100:1 probes may be used. There are also probes that contain switches to select 10:1 or direct (1:1) ratios, but the latter setting has significant capacitance (tens of pF) at the probe tip, because the whole cable's capacitance is then directly connected.

Most oscilloscopes provide for probe attenuation factors, displaying the effective sensitivity at the probe tip. Historically, some auto-sensing circuitry used indicator lamps behind translucent windows in the panel to illuminate different parts of the sensitivity scale. To do so, the probe connectors (modified BNCs) had an extra contact to define the probe's attenuation. (A certain value of resistor, connected to ground, "encodes" the attenuation.) Because probes wear out, and because the auto-sensing circuitry is not compatible between different oscilloscope makes, auto-sensing probe scaling is not foolproof. Likewise, manually setting the probe attenuation is prone to user error. Setting the probe scaling incorrectly is a common error, and throws the reading off by a factor of 10.

Special high voltage probes form compensated attenuators with the oscilloscope input. These have a large probe body, and some require partly filling a canister surrounding the series resistor with volatile liquid fluorocarbon to displace air. The oscilloscope end has a box with several waveform-trimming adjustments. For safety, a barrier disc keeps the user's fingers away from the point being examined. Maximum voltage is in the low tens of kV. (Observing a high voltage ramp can create a staircase waveform with steps at different points every repetition, until the probe tip is in contact. Until then, a tiny arc charges the probe tip, and its capacitance holds the voltage (open circuit). As the voltage continues to climb, another tiny arc charges the tip further.)

There are also current probes, with cores that surround the conductor carrying current to be examined. One type has a hole for the conductor, and requires that the wire be passed through the hole for semi-permanent or permanent mounting. However, other types, used for temporary testing, have a two-part core that can be clamped around a wire. Inside the probe, a coil wound around the core provides a current into an appropriate load, and the voltage across that load is proportional to current. This type of probe only senses AC.

A more-sophisticated probe includes a magnetic flux sensor (Hall effect sensor) in the magnetic circuit. The probe connects to an amplifier, which feeds (low frequency) current into the coil to cancel the sensed field; the magnitude of the current provides the low-frequency part of the current waveform, right down to DC. The coil still picks up high frequencies. There is a combining network akin to a loudspeaker crossover.

Front panel controls

[edit]Focus control

[edit]This control adjusts CRT focus to obtain the sharpest, most-detailed trace. In practice, focus must be adjusted slightly when observing very different signals, so it must be an external control. The control varies the voltage applied to a focusing anode within the CRT. Flat-panel displays do not need this control.

Intensity control

[edit]This adjusts trace brightness. Slow traces on CRT oscilloscopes need less, and fast ones, especially if not often repeated, require more brightness. On flat panels, however, trace brightness is essentially independent of sweep speed, because the internal signal processing effectively synthesizes the display from the digitized data.

Astigmatism

[edit]This control may instead be called "shape" or "spot shape". It adjusts the voltage on the last CRT anode (immediately next to the Y deflection plates). For a circular spot, the final anode must be at the same potential as both of the Y-plates (for a centred spot the Y-plate voltages must be the same). If the anode is made more positive, the spot becomes elliptical in the X-plane as the more negative Y-plates will repel the beam. If the anode is made more negative, the spot becomes elliptical in the Y-plane as the more positive Y-plates will attract the beam. This control may be absent from simpler oscilloscope designs or may even be an internal control. It is not necessary with flat panel displays.

Beam finder

[edit]Modern oscilloscopes have direct-coupled deflection amplifiers, which means the trace could be deflected off-screen. They also might have their beam blanked without the operator knowing it. To help in restoring a visible display, the beam finder circuit overrides any blanking and limits the beam deflection to the visible portion of the screen. Beam-finder circuits often distort the trace while activated.

Graticule

[edit]The graticule is a grid of lines that serve as reference marks for measuring the displayed trace. These markings, whether located directly on the screen or on a removable plastic filter, usually consist of a 1 cm grid with closer tick marks (often at 2 mm) on the centre vertical and horizontal axis. One expects to see ten major divisions across the screen; the number of vertical major divisions varies. Comparing the grid markings with the waveform permits one to measure both voltage (vertical axis) and time (horizontal axis). Frequency can also be determined by measuring the waveform period and calculating its reciprocal.

On old and lower-cost CRT oscilloscopes the graticule is a sheet of plastic, often with light-diffusing markings and concealed lamps at the edge of the graticule. The lamps had a brightness control. Higher-cost instruments have the graticule marked on the inside face of the CRT, to eliminate parallax errors; better ones also had adjustable edge illumination with diffusing markings. (Diffusing markings appear bright.) Digital oscilloscopes, however, generate the graticule markings on the display in the same way as the trace.

External graticules also protect the glass face of the CRT from accidental impact. Some CRT oscilloscopes with internal graticules have an unmarked tinted sheet plastic light filter to enhance trace contrast; this also serves to protect the faceplate of the CRT.

Accuracy and resolution of measurements using a graticule is relatively limited; better instruments sometimes have movable bright markers on the trace. These permit internal circuits to make more refined measurements.

Both calibrated vertical sensitivity and calibrated horizontal time are set in 1 – 2 – 5 – 10 steps. This leads, however, to some awkward interpretations of minor divisions.

Digital oscilloscopes generate the graticule digitally. The scale, spacing, etc., of the graticule can therefore be varied, and accuracy of readings may be improved.

Timebase controls

[edit]

These select the horizontal speed of the CRT's spot as it creates the trace; this process is commonly referred to as the sweep. In all but the least-costly modern oscilloscopes, the sweep speed is selectable and calibrated in units of time per major graticule division. Quite a wide range of sweep speeds is generally provided, from seconds to as fast as picoseconds (in the fastest) per division. Usually, a continuously-variable control (often a knob in front of the calibrated selector knob) offers uncalibrated speeds, typically slower than calibrated. This control provides a range somewhat greater than the calibrated steps, making any speed between the steps available.

Holdoff control

[edit]Some higher-end analog oscilloscopes have a holdoff control. This sets a time after a trigger during which the sweep circuit cannot be triggered again. It helps provide a stable display of repetitive events in which some triggers would create confusing displays. It is usually set to minimum, because a longer time decreases the number of sweeps per second, resulting in a dimmer trace. See Holdoff for a more detailed description.

Vertical sensitivity, coupling, and polarity controls

[edit]To accommodate a wide range of input amplitudes, a switch selects calibrated sensitivity of the vertical deflection. Another control, often in front of the calibrated selector knob, offers a continuously variable sensitivity over a limited range from calibrated to less-sensitive settings.

Often the observed signal is offset by a steady component, and only the changes are of interest. An input coupling switch in the "AC" position connects a capacitor in series with the input that blocks low-frequency signals and DC. However, when the signal has a fixed offset of interest, or changes slowly, the user will usually prefer "DC" coupling, which bypasses any such capacitor. Most oscilloscopes offer the DC input option. For convenience, to see where zero volts input currently shows on the screen, many oscilloscopes have a third switch position (usually labeled "GND" for ground) that disconnects the input and grounds it. Often, in this case, the user centers the trace with the vertical position control.

Better oscilloscopes have a polarity selector. Normally, a positive input moves the trace upward; the polarity selector offers an "inverting" option, in which a positive-going signal deflects the trace downward.

Vertical position control

[edit]

The vertical position control moves the whole displayed trace up and down. It is used to set the no-input trace exactly on the center line of the graticule, but also permits offsetting vertically by a limited amount. With direct coupling, adjustment of this control can compensate for a limited DC component of an input.

Horizontal sensitivity control

[edit]This control is found only on more elaborate oscilloscopes; it offers adjustable sensitivity for external horizontal inputs. It is only active when the instrument is in X-Y mode, i.e. the internal horizontal sweep is turned off.

Horizontal position control

[edit]

The horizontal position control moves the display sidewise. It usually sets the left end of the trace at the left edge of the graticule, but it can displace the whole trace when desired. This control also moves the X-Y mode traces sidewise in some instruments, and can compensate for a limited DC component as for vertical position.

Dual-trace controls

[edit]

Each input channel usually has its own set of sensitivity, coupling, and position controls, though some four-trace oscilloscopes have only minimal controls for their third and fourth channels.

Dual-trace oscilloscopes have a mode switch to select either channel alone, both channels, or (in some) an X‑Y display, which uses the second channel for X deflection. When both channels are displayed, the type of channel switching can be selected on some oscilloscopes; on others, the type depends upon timebase setting. If manually selectable, channel switching can be free-running (asynchronous), or between consecutive sweeps. Some Philips dual-trace analog oscilloscopes had a fast analog multiplier, and provided a display of the product of the input channels.

Multiple-trace oscilloscopes have a switch for each channel to enable or disable display of the channel's trace.

Delayed-sweep controls

[edit]These include controls for the delayed-sweep timebase, which is calibrated, and often also variable. The slowest speed is several steps faster than the slowest main sweep speed, though the fastest is generally the same. A calibrated multiturn delay time control offers wide range, high resolution delay settings; it spans the full duration of the main sweep, and its reading corresponds to graticule divisions (but with much finer precision). Its accuracy is also superior to that of the display.

A switch selects display modes: Main sweep only, with a brightened region showing when the delayed sweep is advancing, delayed sweep only, or (on some) a combination mode.

Good CRT oscilloscopes include a delayed-sweep intensity control, to allow for the dimmer trace of a much-faster delayed sweep which nevertheless occurs only once per main sweep. Such oscilloscopes also are likely to have a trace separation control for multiplexed display of both the main and delayed sweeps together.

Sweep trigger controls

[edit]A switch selects the trigger source. It can be an external input, one of the vertical channels of a dual or multiple-trace oscilloscope, or the AC line (mains) frequency. Another switch enables or disables auto trigger mode, or selects single sweep, if provided in the oscilloscope. Either a spring-return switch position or a pushbutton arms single sweeps.

A trigger level control varies the voltage required to generate a trigger, and the slope switch selects positive-going or negative-going polarity at the selected trigger level.

Basic types of sweep

[edit]Triggered sweep

[edit]

To display events with unchanging or slowly (visibly) changing waveforms, but occurring at times that may not be evenly spaced, modern oscilloscopes have triggered sweeps. Compared to older, simpler oscilloscopes with continuously-running sweep oscillators, triggered-sweep oscilloscopes are markedly more versatile.

A triggered sweep starts at a selected point on the signal, providing a stable display. In this way, triggering allows the display of periodic signals such as sine waves and square waves, as well as nonperiodic signals such as single pulses, or pulses that do not recur at a fixed rate.

With triggered sweeps, the scope blanks the beam and starts to reset the sweep circuit each time the beam reaches the extreme right side of the screen. For a period of time, called holdoff, (extendable by a front-panel control on some better oscilloscopes), the sweep circuit resets completely and ignores triggers. Once holdoff expires, the next trigger starts a sweep. The trigger event is usually the input waveform reaching some user-specified threshold voltage (trigger level) in the specified direction (going positive or going negative—trigger polarity).

In some cases, variable holdoff time can be useful to make the sweep ignore interfering triggers that occur before the events to be observed. In the case of repetitive, but complex waveforms, variable holdoff can provide a stable display that could not otherwise be achieved.

Holdoff

[edit]Trigger holdoff defines a certain period following a trigger during which the sweep cannot be triggered again. This makes it easier to establish a stable view of a waveform with multiple edges, which would otherwise cause additional triggers.[11]

Example

[edit]Imagine the following repeating waveform:

The green line is the waveform, the red vertical partial line represents the location of the trigger, and the yellow line represents the trigger level. If the scope was simply set to trigger on every rising edge, this waveform would cause three triggers for each cycle:

Assuming the signal is fairly high frequency, the scope display would probably look something like this:

On an actual scope, each trigger would be the same channel, so all would be the same color.

It is desirable for the scope to trigger on only one edge per cycle, so it is necessary to set the holdoff at slightly less than the period of the waveform. This prevents triggering from occurring more than once per cycle, but still lets it trigger on the first edge of the next cycle.

Automatic sweep mode

[edit]Triggered sweeps can display a blank screen if there are no triggers. To avoid this, these sweeps include a timing circuit that generates free-running triggers so a trace is always visible. This is referred to as "auto sweep" or "automatic sweep" in the controls. Once triggers arrive, the timer stops providing pseudo-triggers. The user will usually disable automatic sweep when observing low repetition rates.

Recurrent sweeps

[edit]If the input signal is periodic, the sweep repetition rate can be adjusted to display a few cycles of the waveform. Early (tube) oscilloscopes and lowest-cost oscilloscopes have sweep oscillators that run continuously, and are uncalibrated. Such oscilloscopes are very simple, comparatively inexpensive, and were useful in radio servicing and some TV servicing. Measuring voltage or time is possible, but only with extra equipment, and is quite inconvenient. They are primarily qualitative instruments.

They have a few (widely spaced) frequency ranges, and relatively wide-range continuous frequency control within a given range. In use, the sweep frequency is set to slightly lower than some submultiple of the input frequency, to display typically at least two cycles of the input signal (so all details are visible). A very simple control feeds an adjustable amount of the vertical signal (or possibly, a related external signal) to the sweep oscillator. The signal triggers beam blanking and a sweep retrace sooner than it would occur free-running, and the display becomes stable.

Single sweeps

[edit]Some oscilloscopes offer these. The user manually arms the sweep circuit (typically by a pushbutton or equivalent). "Armed" means it is ready to respond to a trigger. Once the sweep completes, it resets, and does not sweep again until re-armed. This mode, combined with an oscilloscope camera, captures single-shot events.

Types of trigger include:

- external trigger, a pulse from an external source connected to a dedicated input on the scope.

- edge trigger, an edge detector that generates a pulse when the input signal crosses a specified threshold voltage in a specified direction. These are the most common types of triggers; the level control sets the threshold voltage, and the slope control selects the direction (negative or positive-going). (The first sentence of the description also applies to the inputs to some digital logic circuits; those inputs have fixed threshold and polarity response.)

- video trigger, also known as TV trigger, a circuit that extracts synchronizing pulses from video formats such as PAL and NTSC and triggers the timebase on every line, a specified line, every field, or every frame. This circuit is typically found in a waveform monitor device, though some better oscilloscopes include this function.

- delayed trigger, which waits a specified time after an edge trigger before starting the sweep. As described under delayed sweeps, a trigger delay circuit (typically the main sweep) extends this delay to a known and adjustable interval. In this way, the operator can examine a particular pulse in a long train of pulses.

Some recent designs of oscilloscopes include more sophisticated triggering schemes; these are described toward the end of this article.

Delayed sweeps

[edit]More sophisticated analog oscilloscopes contain a second timebase for a delayed sweep. A delayed sweep provides a very detailed look at some small selected portion of the main timebase. The main timebase serves as a controllable delay, after which the delayed timebase starts. This can start when the delay expires, or can be triggered (only) after the delay expires. Ordinarily, the delayed timebase is set for a faster sweep, sometimes much faster, such as 1000:1. At extreme ratios, jitter in the delays on consecutive main sweeps degrades the display, but delayed-sweep triggers can overcome this.

The display shows the vertical signal in one of several modes: the main timebase, or the delayed timebase only, or a combination thereof. When the delayed sweep is active, the main sweep trace brightens while the delayed sweep is advancing. In one combination mode, provided only on some oscilloscopes, the trace changes from the main sweep to the delayed sweep once the delayed sweep starts, though less of the delayed fast sweep is visible for longer delays. Another combination mode multiplexes (alternates) the main and delayed sweeps so that both appear at once; a trace separation control displaces them. DSOs can display waveforms this way, without offering a delayed timebase as such.

Dual and multiple-trace oscilloscopes

[edit]Oscilloscopes with two vertical inputs, referred to as dual-trace oscilloscopes, are extremely useful and commonplace. Using a single-beam CRT, they multiplex the inputs, usually switching between them fast enough to display two traces apparently at once. Less common are oscilloscopes with more traces; four inputs are common among these, but a few (Kikusui, for one) offered a display of the sweep trigger signal if desired. Some multi-trace oscilloscopes use the external trigger input as an optional vertical input, and some have third and fourth channels with only minimal controls. In all cases, the inputs, when independently displayed, are time-multiplexed, but dual-trace oscilloscopes often can add their inputs to display a real-time analog sum. Inverting one channel while adding them together results in a display of the differences between them, provided neither channel is overloaded. This difference mode can provide a moderate-performance differential input.)

Switching channels can be asynchronous, i.e. free-running, with respect to the sweep frequency; or it can be done after each horizontal sweep is complete. Asynchronous switching is usually designated "Chopped", while sweep-synchronized is designated "Alt[ernate]". A given channel is alternately connected and disconnected, leading to the term "chopped". Multi-trace oscilloscopes also switch channels either in chopped or alternate modes.

In general, chopped mode is better for slower sweeps. It is possible for the internal chopping rate to be a multiple of the sweep repetition rate, creating blanks in the traces, but in practice this is rarely a problem. The gaps in one trace are overwritten by traces of the following sweep. A few oscilloscopes had a modulated chopping rate to avoid this occasional problem. Alternate mode, however, is better for faster sweeps.

True dual-beam CRT oscilloscopes did exist, but were not common. One type (Cossor, U.K.) had a beam-splitter plate in its CRT, and single-ended deflection following the splitter. Others had two complete electron guns, requiring tight control of axial (rotational) mechanical alignment in manufacturing the CRT. Beam-splitter types had horizontal deflection common to both vertical channels, but dual-gun oscilloscopes could have separate time bases, or use one time base for both channels. Multiple-gun CRTs (up to ten guns) were made in past decades. With ten guns, the envelope (bulb) was cylindrical throughout its length. (Also see "CRT Invention" in Oscilloscope history.)

The vertical amplifier

[edit]In an analog oscilloscope, the vertical amplifier acquires the signal[s] to be displayed and provides a signal large enough to deflect the CRT's beam. In better oscilloscopes, it delays the signal by a fraction of a microsecond. The maximum deflection is at least somewhat beyond the edges of the graticule, and more typically some distance off-screen. The amplifier has to have low distortion to display its input accurately (it must be linear), and it has to recover quickly from overloads. As well, its time-domain response has to represent transients accurately—minimal overshoot, rounding, and tilt of a flat pulse top.

A vertical input goes to a frequency-compensated step attenuator to reduce large signals to prevent overload. The attenuator feeds one or more low-level stages, which in turn feed gain stages (and a delay-line driver if there is a delay). Subsequent gain stages lead to the final output stage, which develops a large signal swing (tens of volts, sometimes over 100 volts) for CRT electrostatic deflection.

In dual and multiple-trace oscilloscopes, an internal electronic switch selects the relatively low-level output of one channel's early-stage amplifier and sends it to the following stages of the vertical amplifier.

In free-running ("chopped") mode, the oscillator (which may be simply a different operating mode of the switch driver) blanks the beam before switching, and unblanks it only after the switching transients have settled.

Part way through the amplifier is a feed to the sweep trigger circuits, for internal triggering from the signal. This feed would be from an individual channel's amplifier in a dual or multi-trace oscilloscope, the channel depending upon the setting of the trigger source selector.

This feed precedes the delay (if there is one), which allows the sweep circuit to unblank the CRT and start the forward sweep, so the CRT can show the triggering event. High-quality analog delays add a modest cost to an oscilloscope, and are omitted in cost-sensitive oscilloscopes.

The delay, itself, comes from a special cable with a pair of conductors wound around a flexible, magnetically soft core. The coiling provides distributed inductance, while a conductive layer close to the wires provides distributed capacitance. The combination is a wideband transmission line with considerable delay per unit length. Both ends of the delay cable require matched impedances to avoid reflections.

X-Y mode

[edit]

Most modern oscilloscopes have several inputs for voltages, and thus can be used to plot one varying voltage versus another. This is especially useful for graphing I-V curves (current versus voltage characteristics) for components such as diodes, as well as Lissajous figures. Lissajous figures are an example of how an oscilloscope can be used to track phase differences between multiple input signals. This is very frequently used in broadcast engineering to plot the left and right stereophonic channels, to ensure that the stereo generator is calibrated properly. Historically, stable Lissajous figures were used to show that two sine waves had a relatively simple frequency relationship, a numerically-small ratio. They also indicated phase difference between two sine waves of the same frequency.

The X-Y mode also lets the oscilloscope serve as a vector monitor to display images or user interfaces. Many early games, such as Tennis for Two, used an oscilloscope as an output device.[12]

Complete loss of signal in an X-Y CRT display means that the beam is stationary, striking a small spot. This risks burning the phosphor if the brightness is too high. Such damage was more common in older scopes as the phosphors previously used burned more easily. Some dedicated X-Y displays reduce beam current greatly, or blank the display entirely, if there are no inputs present.

Z input

[edit]Some analogue oscilloscopes feature a Z input. This is generally an input terminal that connects directly to the CRT grid (usually via a coupling capacitor). This allows an external signal to either increase (if positive) or decrease (if negative) the brightness of the trace, even allowing it to be totally blanked. The voltage range to achieve cut-off to a brightened display is of the order of 10–20 volts depending on the CRT characteristics.

An example of a practical application is if a pair of sine waves of known frequency are used to generate a circular Lissajous figure and a higher unknown frequency is applied to the Z input. This turns the continuous circle into a circle of dots. The number of dots multiplied by the X-Y frequency gives the Z frequency. This technique only works if the Z frequency is an integer ratio of the X-Y frequency and only if it is not so large that the dots become so numerous that they are difficult to count.

Bandwidth

[edit]As with all practical instruments, oscilloscopes do not respond equally to all possible input frequencies. The range of sinusoid frequencies an oscilloscope can usefully display is referred to as its bandwidth. Bandwidth applies primarily to the Y-axis, though the X-axis sweeps must be fast enough to show the highest-frequency waveforms.

The bandwidth is defined as the frequency at which the sensitivity is 0.707 of the sensitivity at DC or the lowest AC frequency (a drop of 3 dB).[13] The oscilloscope's response drops off rapidly as the input frequency rises above that point. Within the stated bandwidth the response is not necessarily exactly uniform (or "flat"), but should always fall within a +0 to −3 dB range. One source[13] says there is a noticeable effect on the accuracy of voltage measurements at only 20 percent of the stated bandwidth. Some oscilloscopes' specifications do include a narrower tolerance range within the stated bandwidth.

Probes also have bandwidth limits and must be chosen and used to handle the frequencies of interest properly. To achieve the flattest response, most probes must be "compensated" (an adjustment performed using a test signal from the oscilloscope) to allow for the reactance of the probe's cable.

Another related specification is rise time. This is the time taken between 10% and 90% of the maximum amplitude response at the leading edge of a pulse. It is related to the bandwidth approximately by:

Bandwidth in Hz × rise time in seconds = 0.35.[14]

For example, an oscilloscope with a rise time of 1 nanosecond would have a bandwidth of 350 MHz.

In analog instruments, the bandwidth of the oscilloscope is limited by the vertical amplifiers and the CRT or other display subsystem. In digital instruments, the sampling rate of the analog-to-digital converter (ADC) is a factor, but the stated analog bandwidth (and therefore the overall bandwidth of the instrument) is usually less than the ADC's Nyquist frequency. This is due to limitations in the analog signal amplifier, deliberate design of the anti-aliasing filter that precedes the ADC, or both.

For a digital oscilloscope, a rule of thumb is that the continuous sampling rate should be ten times the highest frequency desired to resolve; for example a 20 megasample/second rate would be applicable for measuring signals up to about 2 MHz. This lets the anti-aliasing filter be designed with a 3 dB down point of 2 MHz and an effective cutoff at 10 MHz (the Nyquist frequency), avoiding the artifacts of a very steep ("brick-wall") filter.

A sampling oscilloscope can display signals of considerably higher frequency than the sampling rate if the signals are exactly, or nearly, repetitive. It does this by taking one sample from each successive repetition of the input waveform, each sample being at an increased time interval from the trigger event. The waveform is then displayed from these collected samples. This mechanism is referred to as "equivalent-time sampling".[15] Some oscilloscopes can operate in either this mode or in the more traditional "real-time" mode at the operator's choice.

Waveform interval and sampling interval

[edit]For digital oscilloscopes, waveform interval is defined as the time interval between adjacent points of a displayed waveform while sampling interval is defined as the time interval between adjacent gathered samples (= 1 / sampling frequency), and the waveform interval is usually longer than the sample interval.[16] In other words, the displayed waveform is an aggregation of the gathered samples (e.g., each displayed point is the average over each waveform interval).

Other features

[edit]

Some oscilloscopes have cursors. These are lines that can be moved about the screen to measure the time interval between two points, or the difference between two voltages. A few older oscilloscopes simply brightened the trace at movable locations. These cursors are more accurate than visual estimates referring to graticule lines.[17][18]

Better quality general purpose oscilloscopes include a calibration signal for setting up the compensation of test probes; this is (often) a 1 kHz square-wave signal of a definite peak-to-peak voltage available at a test terminal on the front panel. Some better oscilloscopes also have a squared-off loop for checking and adjusting current probes.

Sometimes a user wants to see an event that happens only occasionally. To catch these events, some oscilloscopes—called storage scopes—preserve the most recent sweep on the screen. This was originally achieved with a special CRT, a storage tube, which retained the image of even a very brief event for a long time.

Some digital oscilloscopes can sweep at speeds as slow as once per hour, emulating a strip chart recorder. That is, the signal scrolls across the screen from right to left. Most oscilloscopes with this facility switch from a sweep to a strip-chart mode at about one sweep per ten seconds. This is because otherwise, the scope looks broken: it is collecting data, but the dot cannot be seen.

All but the simplest models of current oscilloscopes more often use digital signal sampling. Samples feed fast analog-to-digital converters, following which all signal processing (and storage) is digital.

Many oscilloscopes accommodate plug-in modules for different purposes, e.g., high-sensitivity amplifiers of relatively narrow bandwidth, differential amplifiers, amplifiers with four or more channels, sampling plugins for repetitive signals of very high frequency, and special-purpose plugins, including audio/ultrasonic spectrum analyzers, and stable-offset-voltage direct-coupled channels with relatively high gain.

Examples of use

[edit]

One of the most frequent uses of scopes is troubleshooting malfunctioning electronic equipment. For example, where a voltmeter may show a totally unexpected voltage, a scope may reveal that the circuit is oscillating. In other cases the precise shape or timing of a pulse is important.

In a piece of electronic equipment, for example, the connections between stages (e.g., electronic mixers, electronic oscillators, amplifiers) may be 'probed' for the expected signal, using the scope as a simple signal tracer. If the expected signal is absent or incorrect, some preceding stage of the electronics is not operating correctly. Since most failures occur because of a single faulty component, each measurement can show that some of the stages of a complex piece of equipment either work, or probably did not cause the fault.

Once the faulty stage is found, further probing can usually tell a skilled technician exactly which component has failed. Once the component is replaced, the unit can be restored to service, or at least the next fault can be isolated. This sort of troubleshooting is typical of radio and TV receivers, as well as audio amplifiers, but can apply to quite different devices such as electronic motor drives.

Another use is to check newly designed circuitry. Often, a newly designed circuit misbehaves because of design errors, bad voltage levels, electrical noise etc. Digital electronics usually operate from a clock, so a dual-trace scope showing both the clock signal and a test signal dependent upon the clock is useful. Storage scopes are helpful for "capturing" rare electronic events that cause defective operation.

Oscilloscopes are often used during real-time software development to check, among other things, missed deadlines and worst-case latencies.[19]

Pictures of use

[edit]-

Heterodyne

-

AC hum on sound

-

Sum of a low-frequency and a high-frequency signal

-

Bad filter on sine

-

Dual trace, showing different time bases on each trace

Automotive use

[edit]First appearing in the 1970s for ignition system analysis, automotive oscilloscopes are becoming an important workshop tool for testing sensors and output signals on electronic engine management systems, braking and stability systems. Some oscilloscopes can trigger and decode serial bus messages, such as the CAN bus commonly used in automotive applications.

Software

[edit]Many oscilloscopes today provide one or more external interfaces to allow remote instrument control by external software. These interfaces (or buses) include GPIB, Ethernet, serial port, USB and Wi-Fi.

Types and models

[edit]The following section is a brief summary of various types and models available. For a detailed discussion, refer to the other article.

Cathode-ray oscilloscope (CRO)

[edit]

The earliest and simplest type of oscilloscope consisted of a CRT, a vertical amplifier, a timebase, a horizontal amplifier and a power supply. These are now called "analog" scopes to distinguish them from the "digital" scopes that became common in the 1990s and later.

Analog scopes do not necessarily include a calibrated reference grid for size measurement of waves, and they may not display waves in the traditional sense of a line segment sweeping from left to right. Instead, they could be used for signal analysis by feeding a reference signal into one axis and the signal to measure into the other axis. For an oscillating reference and measurement signal, this results in a complex looping pattern referred to as a Lissajous figure. The shape of the curve can be interpreted to identify properties of the measurement signal in relation to the reference signal and is useful across a wide range of oscillation frequencies.

Dual-beam oscilloscope

[edit]The dual-beam analog oscilloscope can display two signals simultaneously. A special dual-beam CRT generates and deflects two separate beams. Multi-trace analog oscilloscopes can simulate a dual-beam display with chop and alternate sweeps—but those features do not provide simultaneous displays. (Real-time digital oscilloscopes offer the same benefits of a dual-beam oscilloscope, but they do not require a dual-beam display.) The disadvantages of the dual trace oscilloscope are that it cannot switch quickly between traces, and cannot capture two fast transient events. A dual beam oscilloscope avoids those problems.

Analog storage oscilloscope

[edit]Trace storage is an extra feature available on some analog scopes; they used direct-view storage CRTs. Storage allows a trace pattern that normally would decay in a fraction of a second to remain on the screen for several minutes or longer. An electrical circuit can then be deliberately activated to store and erase the trace on the screen.

Digital oscilloscopes

[edit]

While analog devices use continually varying voltages, digital devices use numbers that correspond to samples of the voltage. In the case of digital oscilloscopes, an analog-to-digital converter (ADC) changes the measured voltages into digital information.

The digital storage oscilloscope, or DSO for short, is the standard type of oscilloscope today for the majority of industrial applications, and thanks to the low costs of entry-level oscilloscopes even for hobbyists. It replaces the electrostatic storage method in analog storage scopes with digital memory, which stores sample data as long as required without degradation and displays it without the brightness issues of storage-type CRTs. It also allows complex processing of the signal by high-speed digital signal processing circuits.[1]

A standard DSO is limited to capturing signals with a bandwidth of less than half the sampling rate of the ADC (called the Nyquist limit). There is a variation of the DSO called the digital sampling oscilloscope which can exceed this limit for certain types of signal, such as high-speed communications signals, where the waveform consists of repeating pulses. This type of DSO deliberately samples at a much lower frequency than the Nyquist limit and then uses signal processing to reconstruct a composite view of a typical pulse.[20]

Mixed-signal oscilloscopes

[edit]A logic analyzer is similar to an oscilloscope, but for each input signal only provides the logic level without the shape of its analog waveform. A mixed-signal oscilloscope (or MSO) meanwhile has two kinds of inputs: a small number of analog channels (typically two or four), and a larger number of logic channels (typically sixteen). It provides the ability to accurately time-correlate analog and logic signals, thus offering a distinct advantage over a separate oscilloscope and logic analyzer. Typically, logic channels may be grouped and displayed as a bus with each bus value displayed at the bottom of the display in hexadecimal or binary. On most MSOs, the trigger can be set across both analog and logic channels.

Mixed-domain oscilloscopes

[edit]A mixed-domain oscilloscope (MDO) is an oscilloscope that comes with an additional RF input which is solely used for dedicated FFT-based spectrum analyzer functionality. Often, this RF input offers a higher bandwidth than the conventional analog input channels. This is in contrast to the FFT functionality of conventional digital oscilloscopes, which use the normal analog inputs. Some MDOs allow time-correlation of events in the time domain (like a specific serial data package) with events happening in the frequency domain (like RF transmissions).

Handheld oscilloscopes

[edit]Handheld oscilloscopes are useful for many test and field service applications. Today, a handheld oscilloscope is usually a digital sampling oscilloscope, using a liquid crystal display.

Many handheld and bench oscilloscopes have the ground reference voltage common to all input channels. If more than one measurement channel is used at the same time, all the input signals must have the same voltage reference, and the shared default reference is the "earth". If there is no differential preamplifier or external signal isolator, this traditional desktop oscilloscope is not suitable for floating measurements. (Occasionally an oscilloscope user breaks the ground pin in the power supply cord of a bench-top oscilloscope in an attempt to isolate the signal common from the earth ground. This practice is unreliable since the entire stray capacitance of the instrument cabinet connects into the circuit. It is also a hazard to break a safety ground connection, and instruction manuals strongly advise against it.)

Some models of oscilloscope have isolated inputs, where the signal reference level terminals are not connected together. Each input channel can be used to make a "floating" measurement with an independent signal reference level. Measurements can be made without tying one side of the oscilloscope input to the circuit signal common or ground reference.

The isolation available is categorized as shown below:

| Overvoltage category | Operating voltage (effective value of AC/DC to ground) | Peak instantaneous voltage (repeated 20 times) | Test resistor |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAT I | 600 V | 2500 V | 30 Ω |

| CAT I | 1000 V | 4000 V | 30 Ω |

| CAT II | 600 V | 4000 V | 12 Ω |

| CAT II | 1000 V | 6000 V | 12 Ω |

| CAT III | 600 V | 6000 V | 2 Ω |

PC-based oscilloscopes

[edit]

Some digital oscilloscope rely on a PC platform for display and control of the instrument. This can be in the form of a standalone oscilloscope with internal PC platform (PC mainboard), or as external oscilloscope which connects through USB or LAN to a separate PC or laptop.

Related instruments

[edit]A large number of instruments used in a variety of technical fields are really oscilloscopes with inputs, calibration, controls, display calibration, etc., specialized and optimized for a particular application. Examples of such oscilloscope-based instruments include waveform monitors for analyzing video levels in television productions and medical devices such as vital function monitors and electrocardiogram and electroencephalogram instruments. In automobile repair, an ignition analyzer is used to show the spark waveforms for each cylinder. All of these are essentially oscilloscopes, performing the basic task of showing the changes in one or more input signals over time in an X‑Y display.

Other instruments convert the results of their measurements to a repetitive electrical signal, and incorporate an oscilloscope as a display element. Such complex measurement systems include spectrum analyzers, transistor analyzers, and time domain reflectometers (TDRs). Unlike an oscilloscope, these instruments automatically generate stimulus or sweep a measurement parameter.

See also

[edit]- Eye pattern

- Phonodeik

- Tennis for Two, an oscilloscope game

- Time-domain reflectometer

- Vectorscope

- Waveform monitor

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Kularatna, Nihal (2003), "Fundamentals of Oscilloscopes", Digital and Analogue Instrumentation: Testing and Measurement, Institution of Engineering and Technology, pp. 165–208, ISBN 978-0-85296-999-1

- ^ How the Cathode Ray Oscillograph Is Used in Radio Servicing Archived 2013-05-24 at the Wayback Machine, National Radio Institute (1943)

- ^ "Cathode-Ray Oscillograph 274A Equipment DuMont Labs, Allen B" (in German). Radiomuseum.org. Archived from the original on 2014-02-03. Retrieved 2014-03-15.

- ^ Marton, L. (1980). "Ferdinand Braun: Forgotten Forefather". In Suesskind, Charles (ed.). Advances in electronics and electron physics. Vol. 50. Academic Press. p. CRT. ISBN 978-0-12-014650-5. Archived from the original on 2014-05-03.

occurs first in a pair of later papers by Zenneck (1899a,b)

- ^ The 20 picofarad value is typical for scope bandwidths around 100 MHz; for example, a 200 MHz Tektronix 7A26 input impedance is 1 MΩ and 22 pF. (Tektronix (1983, p. 271); see also Tektronix (1998, p. 503), "typical high Z 10× passive probe model".) Lower bandwidth scopes used higher capacitances; the 1 MHz Tektronix 7A22 input impedance is 1 MΩ and 47 pF. (Tektronix 1983, pp. 272–273) Higher bandwidth scopes use smaller capacitances. The 500 MHz Tektronix TDS510A input impedance is 1 MΩ and 10 pF. (Tektronix 1998, p. 78)

- ^ Probes are designed for a specific input impedance. They have compensation adjustments with a limited range, so they often cannot be used on different input impedances.

- ^ Wedlock & Roberge (1969)

- ^ Kobbe & Polits (1959)

- ^ Tektronix (1983, p. 426); Tek claims 300 MHz resistive coax at 30 pF per meter; schematic has 5 adjustments.

- ^ Zeidlhack & White (1970)

- ^ Jones, David. "Oscilloscope Trigger Holdoff Tutorial". EEVblog. Archived from the original on 28 January 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- ^ Nosowitz, Dan (2008-11-08). "'Tennis for Two', the World's First Graphical Videogame". Retromodo. Gizmodo. Archived from the original on 2008-12-07. Retrieved 2008-11-09.

- ^ a b Webster, John G. (1999). The Measurement, Instrumentation and Sensors Handbook (illustrated ed.). Springer. pp. 37–24. ISBN 978-3540648307.

- ^ Spitzer, Frank; Howarth, Barry (1972), Principles of modern Instrumentation, New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, p. 119, ISBN 0-03-080208-3

- ^ "Equivalent Time Sampling Oscilloscope vs. Real-Time Oscilloscope" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2015-03-20.

- ^ Horowitz, Paul; Hill, Winfield (2015). "O.2.1 What's different?". The Art of Electronics (3rd and Kindle ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-80926-9.

- ^ Hickman, Ian (2001). Oscilloscopes. Newnes. pp. 4, 20. ISBN 0-7506-4757-4. Retrieved 2022-01-15.

- ^ Herres, David (2020). Oscilloscopes: A Manual for Students, Engineers, and Scientists. Springer Science+Business Media. pp. 120–121. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-53885-9. ISBN 978-3-030-53885-9. S2CID 226749445.

- ^ Marchesotti, M.; Migliardi, M.; Podesta, R. (2006). "A measurement-based analysis of the responsiveness of the Linux kernel". 13th Annual IEEE International Symposium and Workshop on Engineering of Computer-Based Systems (ECBS'06). pp. 10 pp.-408. doi:10.1109/ECBS.2006.9. ISBN 0-7695-2546-6. S2CID 15440587 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Green, Leslie (June 21, 2001), "The alias theorems: practical undersampling for expert engineers", EDN, archived from the original on 20 June 2013, retrieved 11 October 2012

- US 2883619, Kobbe, John R. & Polits, William J., "Electrical Probe", published 1959-04-21

- Tektronix (1983), Tek Products, Tektronix

- Tektronix (1998), Measurement Products Catalog 1998/1999, Tektronix

- Wedlock, Bruce D.; Roberge, James K. (1969), Electronic Components and Measurements, Prentice-Hall, pp. 150–152, Bibcode:1969ecm..book.....W, ISBN 0-13-250464-2

- US 3532982, Zeidlhack, Donald F. & White, Richard K., "Transmission Line Termination Circuit", published 1970-10-06