Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Borescope

View on WikipediaThis article relies largely or entirely on a single source. (November 2014) |

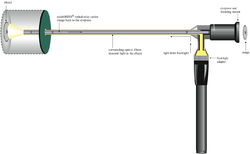

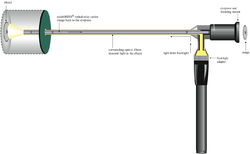

A borescope (occasionally called a boroscope, though this spelling is nonstandard) is an optical instrument designed to assist visual inspection of narrow, difficult-to-reach cavities, consisting of a rigid or flexible tube with an eyepiece or display on one end, an objective lens or camera on the other, linked together by an optical or electrical system in between. The optical system in some instances is accompanied by (typically fiberoptic) illumination to enhance brightness and contrast. An internal image of the illuminated object is formed by the objective lens and magnified by the eyepiece which presents it to the viewer's eye.

Rigid or flexible borescopes may be externally linked to a photography or videography device. For medical use, similar instruments are called endoscopes.

Uses

[edit]Borescopes are used for visual inspection work where the target area is inaccessible by other means, or where accessibility may require destructive, time consuming and/or expensive dismounting activities. Similar devices for use inside the human body are referred to as endoscopes. Borescopes are mostly used in nondestructive testing techniques for recognizing defects or imperfections.

Borescopes are commonly used in the visual inspection of aircraft engines, aeroderivative industrial gas turbines, steam turbines, diesel engines, and automotive and truck engines. Gas and steam turbines require particular attention because of safety and maintenance requirements. Borescope inspection of engines can be used to prevent unnecessary maintenance, which can become extremely costly for large turbines. They are also used in manufacturing of machined or cast parts to inspect critical interior surfaces for burrs, surface finish or complete through-holes. Other common uses include forensic applications in law enforcement and building inspection, and in gunsmithing for inspecting the interior bore of a firearm. In World War II, primitive rigid borescopes were used to examine the interior bores (hence "bore" scope) of large guns for defects.[1]

Flexible versus rigid

[edit]The traditional flexible borescope includes a bundle of optical fibers which divide the image into pixels. It is also known as a fiberscope and can be used to access cavities which are around a bend, such as a combustion chamber or "burner can", in order to view the condition of the compressed air inlets, turbine blades and seals without disassembling the engine. Traditional flexible borescopes suffer from pixelation and pixel crosstalk due to the fiber image guide. Image quality varies widely among different models of flexible borescopes depending on the number of fibers and construction used in the fiber image guide. Some high-end borescopes offer a "visual grid" on image captures to assist in evaluating the size of any area with a problem. For flexible borescopes, articulation mechanism components, range of articulation, field of view and angles of view of the objective lens are also important. Fiber content in the flexible relay is also critical to provide the highest possible resolution to the viewer. Minimal quantity is 10,000 pixels while the best images are obtained with higher numbers of fibers in the 15,000 to 22,000 range for the larger diameter borescopes. The ability to control the light at the end of the insertion tube allows the borescope user to make adjustments that can greatly improve the clarity of video or still images.

Rigid borescopes are similar to fiberscopes but generally provide a superior image at lower cost compared to a flexible borescope. Rigid borescopes have the limitation that access to what is to be viewed must be in a straight line. Rigid borescopes are therefore better suited to certain tasks such as inspecting automotive cylinders, fuel injectors and hydraulic manifold bodies, and gunsmithing. Criteria for selecting a borescope are usually image clarity and access. For similar-quality instruments, the largest rigid borescope that will fit the hole gives the best image. Optical systems in rigid borescopes can be of three basic types: Harold Hopkins rod lenses, achromatic doublets, and gradient index rod lenses. For large-diameter borescopes (over 12 millimetres (0.47 in)), the achromatic doublet relays work quite well, but as the diameter of the borescope tube gets smaller the Hopkins rod lens and gradient index rod lens designs provide superior images. For very small rigid borescopes (under 3 millimetres (0.12 in)), the gradient index lens relays are better.

Video borescopes

[edit]

A video borescope, videoscope, or "inspection camera" is similar to the flexible borescope but uses a miniature video camera at the end of the flexible tube. The end of the insertion tube includes a light which makes it possible to capture video or still images deep within equipment, engines and other dark spaces. As a tool for remote visual inspection the ability to capture video or still images for later inspection is a huge benefit. A display at the other end shows the camera view, and in some models the viewing position can be changed via a joystick or similar control. Because a complex fiber optic waveguide in a traditional borescope is replaced with an inexpensive electrical cable, video borescopes can be much less costly and potentially better resolution (depending on the specifications of the camera). Easy-to-use, battery-powered video borescopes, with 75 mm (3 in) LCD displays of 320×240 pixels or better, became available c. 2012 from several manufacturers and are adequate for some applications. On many of these models, the video camera and flexible tube is submersible. Later models offered improved features, such as better resolution, adjustable illumination or replacing the built-in display with a computer connection, such as a USB cable.

References

[edit]- ^ Popular Mechanics, Dec 45, page 50.