Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Palmolive Building

View on Wikipedia

Palmolive Building | |

The Palmolive Building | |

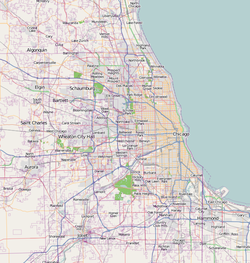

| Location | 919 N Michigan Avenue, Chicago, IL 60611, US |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 41°53′59.41″N 87°37′25.94″W / 41.8998361°N 87.6238722°W |

| Built | 1929 |

| Architect | Holabird & Root |

| Architectural style | Art Deco |

| NRHP reference No. | 03000784 [1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | August 21, 2003 |

| Designated CL | February 16, 2000 |

The Palmolive Building, formerly the Playboy Building, is a 37-story Art Deco building at 919 N. Michigan Avenue in Chicago, Illinois.

History

[edit]Designed by Holabird & Root, the Palmolive Building was completed in 1929 as the home of the Colgate-Palmolive-Peet Company.

Playboy Enterprises purchased the leasehold in 1965 and the structure was renamed the Playboy Building. It was home to the editorial and business offices of Playboy magazine until 1989, when Playboy moved its offices to 680 N Lake Shore Drive. Playboy had sold the leasehold in 1980 and signed a 10-year lease that expired in 1990. The new leaseholder renamed the building 919 North Michigan Avenue.[2]

During the time that Playboy was in the building, the word P-L-A-Y-B-O-Y was spelled out in 9-foot (2.7 m) illuminated letters on the north and south roofline.[3] The building was designated a Chicago Landmark in 2000,[4] and it was added to the federal National Register of Historic Places in 2003.

In 2001, the building was sold to developer Draper and Kramer who, with Booth Hansen Architects, converted it to residential use, with the first two floors dedicated to upscale office and retail space. High-end condos make up the rest of the building. The new owners restored the building's name to the Palmolive Building. The business address remains 919 North Michigan Avenue; however, the residential address is 159 East Walton Place. Notable residents of the building include Vince Vaughn, who bought a 12,000-square-foot (1,100 m2) triplex penthouse encompassing the 35th, 36th and 37th floors for $12 million.[a][6] In February 2013, Vaughn offered the penthouse for sale as a pocket listing for $24.9 million.[b] However, after multiple price cuts he chose in May 2016 to divide the unit in two, offering one for $8.5 million,[c] and the other smaller unit for $4.2 million.[d][7]

Lindbergh Beacon

[edit]

A beacon named for the aviator Charles Lindbergh was added to the building in 1930. It rotated a full 360 degrees and was intended to help guide airplanes safely to Midway Airport. The beacon beamed for several decades, and ceased operation in 1981 following complaints from residents of nearby buildings.[8]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- ^ Storch, Charles (April 9, 1988). "Playboy To Leave 'Playboy Building'". Chicago Tribune. p. B7. Retrieved May 2, 2022.

- ^ "Palmolive Building". Emporis. 2007. Archived from the original on February 19, 2007. Retrieved May 21, 2007.

- ^ "Palmolive Building". Chicago Landmarks. Retrieved January 21, 2015.

- ^ a b c d 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ "The Palmolive Building". Archived from the original on January 26, 2019. Retrieved January 21, 2015.

- ^ Rodkin, Dennis (May 16, 2016). "Vince Vaughn relists Palmolive penthouses". Crain's Chicago Business. Retrieved May 2, 2022.

- ^ Burton, Cheryl (July 5, 2007). "Palmolive Beacon lights up the lake again". WLS News. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved January 10, 2010.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Palmolive Building at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Palmolive Building at Wikimedia Commons