Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

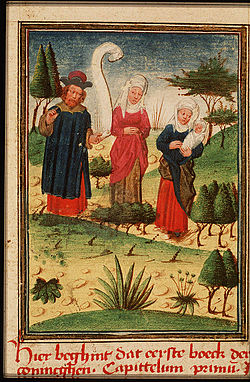

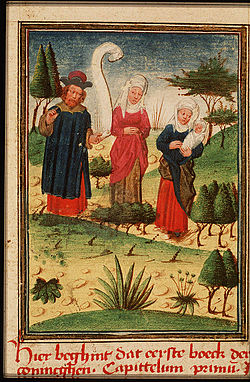

Peninnah

View on Wikipedia

Peninnah (Hebrew: פְּנִנָּה Pəninnā; sometimes transliterated Penina) was one of Elkanah's two wives, briefly mentioned in the first Book of Samuel (1 Samuel 1:2).[1][2] Her name derives from the word פְּנִינָּה (pəninā), meaning "pearl."[3][4]

Biblical account

[edit]Peninnah was less favored than Elkanah's other wife, Hannah; although she had borne him children whilst Hannah was childless, Peninnah also brought grief and disharmony to the household by her mocking of the infertile Hannah.[5] Peninnah would taunt Hannah for being childless. Rabbinical tradition has it that she would grieve Hannah by means of ordinary everyday activities, taking pains to remind her, at all hours of the day, of the difference between them.[6]

According to Jewish writer Lillian Klein, "Because the reader’s sympathies are directed toward the childless Hannah, Peninnah comes across as a malicious woman. In fact, she is probably a literary convention, a foil for the independence and goodness of Hannah, and should be regarded as such."[7]

Eventually, in answer to her desperate prayer, Hannah's womb was opened, and she bore Samuel, and later another three sons and two daughters.[8] After the birth of Samuel, Peninnah is not mentioned again, and 1 Samuel 2:20 says that Eli "would bless Elkanah and his wife", referring to Hannah.

Midrash

[edit]

According to the midrash, Hannah was Elkanah's first wife; after they had been married for ten years, he also took Peninnah as a wife (Pesikta Rabbati 43). The midrash explains that Elkanah was compelled to marry Peninnah because of Hannah's barrenness, which explains his preference for Hannah, his first wife. Another tradition has the initiative to marry Peninnah coming from Hannah, thus comparing her to Sarah and Hagar, and Rachel and Leah, in which the beloved wife, who is barren, initiates the taking of an additional wife in order to produce offspring. The different midrashim highlight the difficulty Peninnah faced living in the shadow of another woman.[9]

A different midrash suggests that Peninnah's actions were in fact noble, and that Peninnah "mocked" the barren Hannah in order to further drive Hannah to pray even harder to God to give her children. She vexed Hannah at Shiloh, thereby causing her distraught rival wife to pray fervently. Thanks to Peninnah, Hannah's prayer was answered, and she gave birth to children.[10]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "I Samuel 1:2". www.sefaria.org. Retrieved 2021-12-21.

- ^ Dr. William Smith's Dictionary of the Bible, Revised and Edited by H. B. Hackett, 1877, Volume III, entry for "Peninnah."

- ^ "doitinHebrew.com - The Talking Online Hebrew Dictionary and Translation Engine. Learn how to say just about anything in Hebrew". www.doitinhebrew.com. Retrieved 2021-12-21.

- ^ Potter, Joseph Lewis; Gesenius, Wilhelm; Robinson, Edward (1877). An English-Hebrew lexicon, being a complete verbal index to Gesenius' Hebrew lexicon. Robarts - University of Toronto. New York, Hurd.

- ^ 1 Samuel 1:4–5.

- ^ Pesikta Rabbati 43

- ^ Klein, Lillian. "Peninnah: Bible", Jewish Women's Archive

- ^ 1 Samuel 2:21.

- ^ Kadari, Tamar. "Peninnah: Midrash and Aggadah", Jewish Women's Archive

- ^ BT Bava Batra 16a