Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Aramaic

View on Wikipedia| Aramaic | |

|---|---|

| ארמית, ܐܪܡܐܝܬ Arāmāiṯ | |

| Region | Fertile Crescent (Levant, Mesopotamia, Sinai and Southeastern Anatolia), Eastern Arabia[1]

Turkey Iraq Syria Iran Kuwait Jordan Israel Lebanon Palestine Egypt Sudan North Africa West Africa Cameroon Chad Somalia Ethiopia Eritrea Djibouti Comoros Oman Yemen Bahrain |

| Ethnicity | Arameans and other Semitic peoples |

Early forms | |

| Dialects | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | Variously:arc – Imperial Aramaicsyc – Classical Syriacmyz – Classical Mandaicxrm – Armazicbjf – Barzani Neo-Aramaicbhn – Bohtan Neo-Aramaichrt – Hertevin Neo-Aramaicaij – Inter-Zab Neo-Aramaictmr – Jewish Babylonian Aramaicjpa – Jewish Palestinian Aramaicjge – Kivrulikqd – Koy Sanjaq Neo-Aramaiclhs – Mlaḥsômid – Modern Mandaicoar – Old Aramaicsam – Samaritan Aramaicsyn – Senaya Neo-Aramaicsyr – Surethuy – Trans-Zab Neo-Aramaictru – Turoyotrg – Urmia Neo-Aramaicamw – Western Neo-Aramaic |

| Glottolog | aram1259 |

| Linguasphere | 12-AAA |

Aramaic (Jewish Babylonian Aramaic: ארמית, romanized: ˀərāmiṯ; Classical Syriac: ܐܪܡܐܝܬ, romanized: arāmāˀiṯ[a]) is a Northwest Semitic language that originated in the ancient region of Syria and quickly spread to Mesopotamia, the southern Levant, Sinai, southeastern Anatolia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Arabia,[3][4] where it has been continually written and spoken in different varieties[5] for over three thousand years.

Aramaic served as a language of public life and administration of ancient kingdoms and empires, particularly the Neo-Assyrian Empire, Neo-Babylonian Empire, and Achaemenid Empire, and also as a language of divine worship and religious study within Judaism, Christianity, and Gnosticism. Several modern varieties of Aramaic are still spoken. The modern eastern branch is spoken by Assyrians, Mandeans, and Mizrahi Jews.[6][7][8][9] Western Aramaic is still spoken by the Muslim and Christian Arameans (Syriacs) in the towns of Maaloula, Bakh'a and nearby Jubb'adin in Syria.[10] Classical varieties are used as liturgical and literary languages in several West Asian churches,[11][12] as well as in Judaism,[13][14] Samaritanism,[15] and Mandaeism.[16] The Aramaic language is now considered endangered, with several varieties used mainly by the older generations.[17] Researchers are working to record and analyze all of the remaining varieties of Neo-Aramaic languages before or in case they become extinct.[18][19]

Aramaic belongs to the Northwest group of the Semitic language family, which also includes the mutually intelligible Canaanite languages such as Hebrew, Edomite, Moabite, Ekronite, Sutean, and Phoenician, as well as Amorite and Ugaritic.[20][21] Aramaic varieties are written in the Aramaic alphabet, a descendant of the Phoenician alphabet. The most prominent variant of this alphabet is the Syriac alphabet, used in the ancient city of Edessa.[22] The Aramaic alphabet also became a base for the creation and adaptation of specific writing systems in some other Semitic languages of West Asia, such as the Hebrew alphabet and the Arabic alphabet.[23]

Early Aramaic inscriptions date from the 11th century BC, placing it among the earliest languages to be written down.[5] Aramaicist Holger Gzella notes, "The linguistic history of Aramaic prior to the appearance of the first textual sources in the ninth century BC remains unknown."[24] Aramaic is also believed by most historians and scholars to have been the primary language spoken by Jesus of Nazareth both for preaching and in everyday life.[25][26]

History

[edit]

Old Aramaic was the language of the ancient Aramean tribes. By around 1000 BC, the Arameans had a string of kingdoms in what is now part of Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Turkey, and the fringes of southern Mesopotamia (Iraq). Aramaic rose to prominence under the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–605 BC), under whose influence Aramaic became a prestige language after being adopted as a lingua franca of the empire by Assyrian kings, and its use was spread throughout Mesopotamia, the Levant and parts of Asia Minor, the Arabian Peninsula, and Ancient Iran under Assyrian rule. At its height, Aramaic was spoken in what is now Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Palestine, Jordan, Kuwait, parts of southeast and south central Turkey, northern parts of the Arabian Peninsula and parts of northwest Iran, as well as the southern Caucasus, having gradually replaced several other related Semitic languages.[27][28][29]

The scribes of the Neo-Assyrian bureaucracy used Aramaic, and this practice was subsequently inherited by the succeeding Neo-Babylonian Empire (605–539 BC) and later by the Achaemenid Empire (539–330 BC).[30] Mediated by scribes that had been trained in the language, highly standardized written Aramaic, named by scholars Imperial Aramaic, progressively also became the lingua franca of public life, trade and commerce throughout Achaemenid territories.[31] Wide use of written Aramaic subsequently led to the adoption of the Aramaic alphabet and, as logograms, some Aramaic vocabulary in the Pahlavi scripts, which were used by several Middle Iranian languages, including Parthian, Middle Persian, Sogdian, and Khwarezmian.[32]

Biblical Aramaic was used in several sections of the Hebrew Bible, including parts of the books of Daniel and Ezra. Aramaic translation of the Bible is known as the Targum.[33][34][35] It was the language of Jesus,[36][37][38] who spoke the Galilean dialect during his public ministry, and of the Jerusalem Talmud, Babylonian Talmud, and Zohar. According to the Babylonian Talmud (Sanhedrin 38b), the language spoken by Adam – the first human in the Bible – was Aramaic.[39]

Some variants of Aramaic are retained as sacred languages by certain religious communities. Most notable among them is Classical Syriac, the liturgical language of Syriac Christianity. It is used by several communities, including the Assyrian Church of the East, the Ancient Church of the East, the Chaldean Catholic Church, the Syriac Orthodox Church, the Syriac Catholic Church, the Maronite Church, and also the Saint Thomas Christians, Syriac Christians of Kerala, India.[40][41][42] One of the liturgical dialects was Mandaic,[43] which besides becoming a vernacular, Neo-Mandaic, also remained the liturgical language of Mandaeism.[44] Syriac was also the liturgical language of several now-extinct gnostic faiths, such as Manichaeism.

Neo-Aramaic languages are still spoken in the 21st century as a first language by many communities of Assyrians, Mizrahi Jews (in particular, the Iraqi Jews), and Mandaeans of the Near East,[45][46] with the main Neo-Aramaic languages being Suret (~240,000 speakers) and Turoyo (~250,000 speakers).[47] Western Neo-Aramaic (~3,000)[48] persists in only two villages in the Anti-Lebanon Mountains in western Syria.[49] They have retained use of the once-dominant lingua franca despite subsequent language shifts experienced throughout the Middle East.

Name

[edit]

The connection between Chaldean, Syriac, and Samaritan as "Aramaic" was first identified in 1679 by German theologian Johann Wilhelm Hilliger.[52][53] In 1819–1821 Ulrich Friedrich Kopp published his Bilder und Schriften der Vorzeit ("Images and Inscriptions of the Past"), in which he established the basis of the paleographical development of the Northwest Semitic scripts.[54] Kopp criticised Jean-Jacques Barthélemy and other scholars who had characterized all the then-known inscriptions and coins as Phoenician, with "everything left to the Phoenicians and nothing to the Arameans, as if they could not have written at all".[55] Kopp noted that some of the words on the Carpentras Stele corresponded to the Aramaic in the Book of Daniel, and in the Book of Ruth.[56]

Josephus and Strabo (the latter citing Posidonius) both stated that the "Syrians" called themselves "Arameans".[57][58][59][60] The Septuagint, the earliest extant full copy of the Hebrew Bible, a Greek translation, used the terms Syria and Syrian where the Masoretic Text, the earliest extant Hebrew copy of the Bible, uses the terms Aramean and Aramaic;[61][62][63] numerous later bibles followed the Septuagint's usage, including the King James Version.[64] This connection between the names Syrian and Aramaic was discussed in 1835 by Étienne Marc Quatremère.[65][66]

In historical sources, Aramaic language is designated by two distinctive groups of terms, first of them represented by endonymic (native) names, and the other one represented by various exonymic (foreign in origin) names. Native (endonymic) terms for Aramaic language were derived from the same word root as the name of its original speakers, the ancient Arameans. Endonymic forms were also adopted in some other languages, like ancient Hebrew. In the Torah (Hebrew Bible), "Aram" is used as a proper name of several people including descendants of Shem,[67] Nahor,[68] and Jacob.[69][70] Ancient Aram, bordering northern Israel and what is now called Syria, is considered the linguistic center of Aramaic, the language of the Arameans who settled the area during the Bronze Age c. 3500 BC.

Unlike in Hebrew, designations for Aramaic language in some other ancient languages were mostly exonymic. In ancient Greek, Aramaic language was most commonly known as the "Syrian language",[65] in relation to the native (non-Greek) inhabitants of the historical region of Syria. Since the name of Syria itself emerged as a variant of Assyria,[71][72] the biblical Ashur,[73] and Akkadian Ashuru,[74] a complex set of semantic phenomena was created, becoming a subject of interest both among ancient writers and modern scholars.

The Koine Greek word Ἑβραϊστί (Hebraïstí) has been translated as "Aramaic" in some versions of the Christian New Testament, as Aramaic was at that time the language commonly spoken by the Jews.[75][76] However, Ἑβραϊστί is consistently used in Koine Greek at this time to mean Hebrew and Συριστί (Syristi) is used to mean Aramaic.[77] In Biblical scholarship, the term "Chaldean" was for many years used as a synonym of Aramaic, due to its use in the book of Daniel and subsequent interpretation by Jerome.[78]

Geographic distribution

[edit]

During the Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian Empires, Arameans began to settle in greater numbers in Babylonia, and later in the heartland of Assyria, also known as the "Arbela triangle" (Assur, Nineveh, and Arbela).[79] The influx eventually resulted in the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–605 BC) adopting an Akkadian-influenced Imperial Aramaic as the lingua franca of its empire.[31] This policy was continued by the short-lived Neo-Babylonian Empire, and both empires became operationally bilingual in written sources, with Aramaic used alongside Akkadian.[80] The Achaemenid Empire (539–323 BC) continued this tradition, and the extensive influence of these empires led to Aramaic gradually becoming the lingua franca of most of western Asia, Anatolia, the Caucasus, and Egypt.[27][29]

Beginning with the rise of the Rashidun Caliphate and the early Muslim conquests in the late seventh century, Arabic gradually replaced Aramaic as the lingua franca of the Near East.[81] However, Aramaic remains a spoken, literary, and liturgical language for local Christians and also some Jews. Aramaic also continues to be spoken by the Assyrians of northern Iraq, northeastern Syria, southeastern Turkey, and northwest Iran, with diaspora communities in Armenia, Georgia, Azerbaijan, and southern Russia. The Mandaeans also continue to use Classical Mandaic as a liturgical language, although most now speak Arabic as their first language.[44] There are still also a small number of first-language speakers of Western Aramaic varieties in isolated villages in western Syria.

Being in contact with other regional languages, some Neo-Aramaic dialects were often engaged in the mutual exchange of influences, particularly with Arabic,[81] Iranian,[82] and Kurdish.[83]

The turbulence of the last two centuries (particularly the Assyrian genocide, also known as Seyfo, "Sword" in Syriac) has seen speakers of first-language and literary Aramaic dispersed throughout the world. However, there are several sizable Assyrian towns in northern Iraq, such as Alqosh, Bakhdida, Bartella, Tesqopa, and Tel Keppe, and numerous small villages, where Aramaic is still the main spoken language, and many large cities in this region also have Suret-speaking communities, particularly Mosul, Erbil, Kirkuk, Dohuk, and al-Hasakah. In modern Israel, the only native Aramaic-speaking population are the Jews of Kurdistan, although the language is dying out.[84] However, Aramaic is also experiencing a revival among Maronites in Israel in Jish.[85]

Aramaic languages and dialects

[edit]Aramaic is often spoken of as a single language but is actually a group of related languages.[86] Some languages differ more from each other than the Romance languages do among themselves. Its long history, extensive literature, and use by different religious communities are all factors in the diversification of the language. Some Aramaic dialects are mutually intelligible, whereas others are not, similar to the situation with modern varieties of Arabic.

Some Aramaic languages are known under different names; for example, Syriac is particularly used to describe the Eastern Aramaic variety spoken by Syriac Christian communities in northern Iraq, southeastern Turkey, northeastern Syria, and northwestern Iran, and the Saint Thomas Christians in Kerala, India. Most dialects can be described as either "Eastern" or "Western", the dividing line being roughly the Euphrates, or slightly west of it.

It is also helpful to distinguish modern living languages, or Neo-Aramaics, and those that are still in use as literary or liturgical languages or are only of interest to scholars. Although there are some exceptions to this rule, this classification gives "Old", "Middle", and "Modern" periods alongside "Eastern" and "Western" areas to distinguish between the various languages and dialects that are Aramaic.

Writing system

[edit]

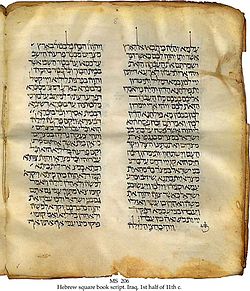

The earliest Aramaic alphabet was based on the Phoenician alphabet. In time, Aramaic developed its distinctive "square" style. The ancient Israelites and other peoples of Canaan adopted this alphabet for writing their own languages. Thus, it is better known as the Hebrew alphabet. This is the writing system used in Biblical Aramaic and other Jewish writing in Aramaic. The other main writing system used for Aramaic was developed by Christian communities: a cursive form known as the Syriac alphabet. A highly modified form of the Aramaic alphabet, the Mandaic alphabet, is used by the Mandaeans.[44]

In addition to these writing systems, certain derivatives of the Aramaic alphabet were used in ancient times by particular groups: the Nabataean alphabet in Petra and the Palmyrene alphabet in Palmyra. In modern times, Turoyo (see below) has sometimes been written in a Latin script.

Periodization

[edit] |

Periodization of historical development of Aramaic language has been the subject of particular interest for scholars, who proposed several types of periodization, based on linguistic, chronological and territorial criteria. Overlapping terminology, used in different periodizations, led to the creation of several polysemic terms, that are used differently among scholars. Terms like: Old Aramaic, Ancient Aramaic, Early Aramaic, Middle Aramaic, Late Aramaic (and some others, like Paleo-Aramaic), were used in various meanings, thus referring (in scope or substance) to different stages in historical development of Aramaic language.[87][88][89]

Most commonly used types of periodization are those of Klaus Beyer and Joseph Fitzmyer.

Periodization of Klaus Beyer (1929–2014):[90]

- Old Aramaic, from the earliest records, to c. 200 AD

- Middle Aramaic, from c. 200 AD, to c. 1200 AD

- Modern Aramaic, from c. 1200 AD, up to the modern times

Periodization of Joseph Fitzmyer (1920–2016):[91]

- Old Aramaic, from the earliest records, to regional prominence c. 700 BC

- Official Aramaic, from c. 700 BC, to c. 200 BC

- Middle Aramaic, from c. 200 BC, to c. 200 AD

- Late Aramaic, from c. 200 AD, to c. 700 AD

- Modern Aramaic, from c. 700 AD, up to the modern times

Recent periodization of Aaron Butts:[92]

- Old Aramaic, from the earliest records, to c. 538 BC

- Achaemenid Aramaic, from c. 538 BC, to c. 333 BC

- Middle Aramaic, from c. 333 BC, to c. 200 AD

- Late Aramaic, from c. 200 AD, to c. 1200 AD

- Neo-Aramaic, from c. 1200 AD, up to the modern times

Old Aramaic

[edit]

Aramaic's long history and diverse and widespread use has led to the development of many divergent varieties, which are sometimes considered dialects, though they have become distinct enough over time that they are now sometimes considered separate languages. Therefore, there is not one singular, static Aramaic language; each time and place rather has had its own variation. The more widely spoken Eastern Aramaic languages are largely restricted to Assyrian, Mandean and Mizrahi Jewish communities in Iraq, northeastern Syria, northwestern Iran, and southeastern Turkey, whilst the severely endangered Western Neo-Aramaic language is spoken by small Christian and Muslim communities in the Anti-Lebanon mountains, and closely related western varieties of Aramaic[94] persisted in Mount Lebanon until as late as the 17th century.[95] The term "Old Aramaic" is used to describe the varieties of the language from its first known use, until the point roughly marked by the rise of the Sasanian Empire (224 AD), dominating the influential, eastern dialect region. As such, the term covers over thirteen centuries of the development of Aramaic. This vast time span includes all Aramaic that is now effectively extinct. Regarding the earliest forms, Beyer suggests that written Aramaic probably dates from the 11th century BC,[96] as it is established by the 10th century, to which he dates the oldest inscriptions of northern Syria. Heinrichs uses the less controversial date of the 9th century,[97] for which there is clear and widespread attestation.

The central phase in the development of Old Aramaic was its official use by the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–608 BC), Neo-Babylonian Empire (620–539 BC), and Achaemenid Empire (500–330 BC). The period before this, dubbed "Ancient Aramaic", saw the development of the language from being spoken in Aramaean city-states to become a major means of communication in diplomacy and trade throughout Mesopotamia, the Levant, and Egypt. After the fall of the Achaemenid Empire, local vernaculars became increasingly prominent, fanning the divergence of an Aramaic dialect continuum and the development of differing written standards.

Ancient Aramaic

[edit]"Ancient Aramaic" refers to the earliest known period of the language, from its origin until it becomes the lingua franca of the Fertile Crescent. It was the language of the Aramean city-states of Damascus, Hamath, and Arpad.[98]

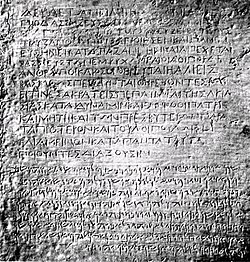

There are inscriptions that evidence the earliest use of the language, dating from the 10th century BC. These inscriptions are mostly diplomatic documents between Aramaean city-states. The alphabet of Aramaic at this early period seems to be based on the Phoenician alphabet, and there is a unity in the written language. It seems that, in time, a more refined alphabet, suited to the needs of the language, began to develop from this in the eastern regions of Aram. Due to increasing Aramean migration eastward, the Western periphery of Assyria became bilingual in Akkadian and Aramean at least as early as the mid-9th century BC. As the Neo-Assyrian Empire conquered Aramean lands west of the Euphrates, Tiglath-Pileser III made Aramaic the Empire's second official language, and it eventually supplanted Akkadian completely.

From 700 BC, the language began to spread in all directions, but lost much of its unity. Different dialects emerged in Assyria, Babylonia, the Levant and Egypt. Around 600 BC, Adon, a Canaanite king, used Aramaic to write to an Egyptian Pharaoh.[99]

Imperial Aramaic

[edit]| Arameans |

|---|

| Syro-Hittite states |

| Aramean kings |

| Aramean cities |

| Sources |

Around 500 BC, following the Achaemenid (Persian) conquest of Mesopotamia under Darius I, Aramaic (as had been used in that region) was adopted by the conquerors as the "vehicle for written communication between the different regions of the vast empire with its different peoples and languages. The use of a single official language, which modern scholarship has dubbed Official Aramaic or Imperial Aramaic,[100][30][101] can be assumed to have greatly contributed to the astonishing success of the Achaemenids in holding their far-flung empire together for as long as they did".[102] In 1955, Richard Frye questioned the classification of Imperial Aramaic as an "official language", noting that no surviving edict expressly and unambiguously accorded that status to any particular language.[103] Frye reclassifies Imperial Aramaic as the lingua franca of the Achaemenid territories, suggesting then that the Achaemenid-era use of Aramaic was more pervasive than generally thought.

Imperial Aramaic was highly standardised; its orthography was based more on historical roots than any spoken dialect, and the inevitable influence of Persian gave the language a new clarity and robust flexibility. For centuries after the fall of the Achaemenid Empire (in 330 BC), Imperial Aramaic – or a version thereof near enough for it to be recognisable – would remain an influence on the various native Iranian languages. Aramaic script and – as ideograms – Aramaic vocabulary would survive as the essential characteristics of the Pahlavi scripts.[104]

One of the largest collections of Imperial Aramaic texts is that of the Persepolis Administrative Archives, found at Persepolis, which number about five hundred.[105] Many of the extant documents witnessing to this form of Aramaic come from Egypt, and Elephantine in particular (see Elephantine papyri). Of them, the best known is the Story of Ahikar, a book of instructive aphorisms quite similar in style to the biblical Book of Proverbs. Consensus as of 2022[update] regards the Aramaic portion of the Biblical book of Daniel (i.e., 2:4b–7:28) as an example of Imperial (Official) Aramaic.[106]

Achaemenid Aramaic is sufficiently uniform that it is often difficult to know where any particular example of the language was written. Only careful examination reveals the occasional loan word from a local language.

A group of thirty Aramaic documents from Bactria have been discovered, and an analysis was published in November 2006. The texts, which were rendered on leather, reflect the use of Aramaic in the 4th century BC Achaemenid administration of Bactria and Sogdia.[107]

Biblical Aramaic

[edit]Biblical Aramaic is the Aramaic found in four discrete sections of the Old Testament:

- Ezra[108] – documents from the Achaemenid period (5th century BC) concerning the restoration of the temple in Jerusalem.

- Daniel[109] – five tales and an apocalyptic vision.[110]

- Jeremiah 10:11 – a single sentence in the middle of a Hebrew text denouncing idolatry.

- Genesis[111] – translation of a Hebrew place-name.

Biblical Aramaic is a somewhat hybrid dialect. It is theorized that some Biblical Aramaic material originated in both Babylonia and Judaea before the fall of the Achaemenid dynasty.

Biblical Aramaic presented various challenges for writers who were engaged in early Biblical studies. Since the time of Jerome of Stridon (d. 420), Aramaic of the Bible was named as "Chaldean" (Chaldaic, Chaldee).[112] That label remained common in early Aramaic studies, and persisted up into the nineteenth century. The "Chaldean misnomer" was eventually abandoned, when modern scholarly analyses showed that Aramaic dialect used in the Hebrew Bible was not related to ancient Chaldeans and their language.[113][114][115]

Post-Achaemenid Aramaic

[edit]

The fall of the Achaemenid Empire (c. 334–330 BC), and its replacement with the newly created political order, imposed by Alexander the Great (d. 323 BC) and his Hellenistic successors, marked an important turning point in the history of Aramaic language. During the early stages of the post-Achaemenid era, public use of Aramaic language was continued, but shared with the newly introduced Greek language. By the year 300 BC, all of the main Aramaic-speaking regions came under political rule of the newly created Seleucid Empire that promoted Hellenistic culture, and favored Greek language as the main language of public life and administration. During the 3rd century BC, Greek overtook Aramaic in many spheres of public communication, particularly in highly Hellenized cities throughout the Seleucid domains. However, Aramaic continued to be used, in its post-Achaemenid form, among upper and literate classes of native Aramaic-speaking communities, and also by local authorities (along with the newly introduced Greek). Post-Achaemenid Aramaic, that bears a relatively close resemblance to that of the Achaemenid period, continued to be used up to the 2nd century BC.[116]

By the end of the 2nd century BC, several variants of Post-Achaemenid Aramaic emerged, bearing regional characteristics. One of them was Hasmonaean Aramaic, the official administrative language of Hasmonaean Judaea (142–37 BC), alongside Hebrew, which was the language preferred in religious and some other public uses (coinage). It influenced the Biblical Aramaic of the Qumran texts, and was the main language of non-biblical theological texts of that community. The major Targums, translations of the Hebrew Bible into Aramaic, were originally composed in Hasmonaean Aramaic. It also appears in quotations in the Mishnah and Tosefta, although smoothed into its later context. It is written quite differently from Achaemenid Aramaic; there is an emphasis on writing as words are pronounced rather than using etymological forms.

The use of written Aramaic in the Achaemenid bureaucracy also precipitated the adoption of Aramaic(-derived) scripts to render a number of Middle Iranian languages. Moreover, many common words, including even pronouns, particles, numerals, and auxiliaries, continued to be written as Aramaic "words" even when writing Middle Iranian languages. In time, in Iranian usage, these Aramaic "words" became disassociated from the Aramaic language and came to be understood as signs (i.e. logograms), much like the symbol '&' is read as "and" in English and the original Latin et is now no longer obvious. Under the early 3rd-century BC Parthian Arsacids, whose government used Greek but whose native language was Parthian, the Parthian language and its Aramaic-derived writing system both gained prestige. This in turn also led to the adoption of the name 'pahlavi' (< parthawi, "of the Parthians") for that writing system. The Persian Sassanids, who succeeded the Parthian Arsacids in the mid-3rd century AD, subsequently inherited/adopted the Parthian-mediated Aramaic-derived writing system for their own Middle Iranian ethnolect as well.[117][118] That particular Middle Iranian dialect, Middle Persian, i.e. the language of Persia proper, subsequently also became a prestige language. Following the conquest of the Sassanids by the Arabs in the 7th-century, the Aramaic-derived writing system was replaced by the Arabic alphabet in all but Zoroastrian usage, which continued to use the name 'pahlavi' for the Aramaic-derived writing system and went on to create the bulk of all Middle Iranian literature in that writing system.

Other regional dialects continued to exist alongside these, often as simple, spoken variants of Aramaic. Early evidence for these vernacular dialects is known only through their influence on words and names in a more standard dialect. However, some of those regional dialects became written languages by the 2nd century BC. These dialects reflect a stream of Aramaic that is not directly dependent on Achaemenid Aramaic, and they also show a clear linguistic diversity between eastern and western regions.

Targumic

[edit]Babylonian Targumic is the later post-Achaemenid dialect found in the Targum Onqelos and Targum Jonathan, the "official" targums. The original, Hasmonaean targums had reached Babylon sometime in the 2nd or 3rd century AD. They were then reworked according to the contemporary dialect of Babylon to create the language of the standard targums. This combination formed the basis of Babylonian Jewish literature for centuries to follow.

Galilean Targumic is similar to Babylonian Targumic. It is the mixing of literary Hasmonaean with the dialect of Galilee. The Hasmonaean targums reached Galilee in the 2nd century AD, and were reworked into this Galilean dialect for local use. The Galilean Targum was not considered an authoritative work by other communities, and documentary evidence shows that its text was amended. From the 11th century AD onwards, once the Babylonian Targum had become normative, the Galilean version became heavily influenced by it.

Babylonian Documentary Aramaic

[edit]Babylonian Documentary Aramaic is a dialect in use from the 3rd century AD onwards. It is the dialect of Babylonian private documents, and, from the 12th century, all Jewish private documents are in Aramaic. It is based on Hasmonaean with very few changes. This was perhaps because many of the documents in BDA are legal documents, the language in them had to be sensible throughout the Jewish community from the start, and Hasmonaean was the old standard.

Nabataean

[edit]Nabataean Aramaic was the written language of the Arab kingdom of Nabataea, whose capital was Petra. The kingdom (c. 200 BC – 106 AD) controlled the region to the east of the Jordan River, the Negev, the Sinai Peninsula, and the northern Hijaz, and supported a wide-ranging trade network. The Nabataeans used imperial Aramaic for written communications, rather than their native Arabic. Nabataean Aramaic developed from Imperial Aramaic, with some influence from Arabic: "l" is often turned into "n", and there are some Arabic loanwords. Arabic influence on Nabataean Aramaic increased over time. Some Nabataean Aramaic inscriptions date from the early days of the kingdom, but most datable inscriptions are from the first four centuries AD. The language is written in a cursive script that was the precursor to the Arabic alphabet. After annexation by the Romans in 106 AD, most of Nabataea was subsumed into the province of Arabia Petraea, the Nabataeans turned to Greek for written communications, and the use of Aramaic declined.

Palmyrene

[edit]Palmyrene Aramaic is the dialect that was in use in the multicultural[119] city state of Palmyra in the Syrian Desert from 44 BC to 274 AD. It was written in a rounded script, which later gave way to cursive Estrangela. Like Nabataean, Palmyrene was influenced by Arabic, but to a much lesser degree.

Eastern dialects

[edit]

In the eastern regions (from Mesopotamia to Persia), dialects like Palmyrene Aramaic and Arsacid Aramaic gradually merged with the regional vernacular dialects, thus creating languages with a foot in Achaemenid and a foot in regional Aramaic.

In the Kingdom of Osroene, founded in 132 BC and centred in Edessa (Urhay), the regional dialect became the official language: Edessan Aramaic (Urhaya), that later came to be known as Classical Syriac. On the upper reaches of the Tigris, East Mesopotamian Aramaic flourished, with evidence from the regions of Hatra and Assur.[120]

Tatian the Assyrian (or Syrian), the author of the gospel harmony the Diatessaron came from Adiabene (Syr. Beth-Hadiab),[121] and perhaps wrote his work (172 AD) in East Mesopotamian rather than Classical Syriac or Greek. In Babylonia, the regional dialect was used by the Jewish community, Jewish Old Babylonian (from c. 70 AD). This everyday language increasingly came under the influence of Biblical Aramaic and Babylonian Targumic.

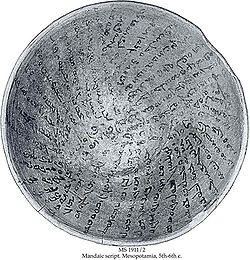

The written form of Mandaic, the language of Mandaeism, was descended from the Arsacid chancery script.[122]

Western dialects

[edit]The western regional dialects of Aramaic followed a similar course to those of the east. They are quite distinct from the eastern dialects and Imperial Aramaic. Aramaic came to coexist with Canaanite dialects, eventually completely displacing Phoenician in the first century BC and Hebrew around the turn of the fourth century AD.

The form of Late Old Western Aramaic used by the Jewish community is best attested, and is usually referred to as Jewish Old Palestinian. Its oldest form is Old East Jordanian, which probably comes from the region of Caesarea Philippi. This is the dialect of the oldest manuscript of the Book of Enoch (c. 170 BC). The next distinct phase of the language is called Old Judaean lasting into the second century AD. Old Judean literature can be found in various inscriptions and personal letters, preserved quotations in the Talmud and receipts from Qumran. Josephus' first, non-extant edition of his The Jewish War was written in Old Judean.

The Old East Jordanian dialect continued to be used into the first century AD by pagan communities living to the east of the Jordan. Their dialect is often then called Pagan Old Palestinian, and it was written in a cursive script somewhat similar to that used for Old Syriac. A Christian Old Palestinian dialect may have arisen from the pagan one, and this dialect may be behind some of the Western Aramaic tendencies found in the otherwise eastern Old Syriac gospels (see Peshitta).

Languages during Jesus' lifetime

[edit]It is generally believed by Christian scholars that in the first century, Jews in Judea primarily spoke Aramaic with a decreasing number using Hebrew as their first language, though many learned Hebrew as a liturgical language. Additionally, Koine Greek was the lingua franca of the Near East in trade, among the Hellenized classes (much like French in the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries in Europe), and in the Roman administration. Latin, the language of the Roman army and higher levels of administration, had almost no impact on the linguistic landscape.

In addition to the formal, literary dialects of Aramaic based on Hasmonean and Babylonian, there were a number of colloquial Aramaic dialects spoken in the southern Levant. Seven Western Aramaic varieties were spoken in the vicinity of Judea in Jesus' time.[123] They were probably distinctive yet mutually intelligible. Old Judean was the prominent dialect of Jerusalem and Judaea. The region of Ein Gedi spoke the Southeast Judaean dialect. Samaritan Aramaic was distinct; it ultimately merged [ʔ], [h], [ħ], and [ʕ] as a glottal stop, only maintaining [ʕ] in the initial position before the vowel [a]. Galilean Aramaic, the dialect of Jesus' home region, is only known from a few place names, the influences on Galilean Targumic, some rabbinic literature, and a few private letters. It seems to have a number of distinctive features, including the collapse of gutturals and the maintenance of diphthongs. In the Transjordan, the various dialects of East Jordanian Aramaic were spoken. In the region of Damascus and the Anti-Lebanon Mountains, Damascene Aramaic was spoken (deduced mostly from Modern Western Aramaic). Finally, as far north as Aleppo, the western dialect of Orontes Aramaic was spoken.

The three languages, especially Hebrew and Aramaic, influenced one another through loanwords and semantic loans. Hebrew words entered Jewish Aramaic. Most were mostly technical religious words, but a few were everyday words like עץ ʿēṣ "wood". Conversely, Aramaic words, such as māmmôn "wealth" were borrowed into Hebrew, and Hebrew words acquired additional senses from Aramaic. For instance, Hebrew: ראוי, romanized: rāʾûi, lit. 'seen' borrowed the sense "worthy, seemly" from Aramaic ḥzî "seen, worthy".

New Testament Greek preserves some semiticisms, including transliterations of Semitic words. Some are Aramaic,[124] like talitha (ταλιθα), which represents the Aramaic noun טליתא ṭalīṯā,[125] and others may be either Hebrew or Aramaic like רבוני Rabbounei (Ραββουνει), which means "my master/great one/teacher" in both languages.[126] Other examples:

- "Talitha kumi" (טליתא קומי)[125]

- "Ephphatha" (אתפתח)[127]

- "Eloi, Eloi, lama sabachthani?" (?אלהי, אלהי, למה שבקתני)[128]

The 2004 film The Passion of the Christ used Aramaic for much of its dialogue, specially reconstructed by a scholar, William Fulco, S.J. Where the appropriate words (in first-century Aramaic) were no longer known, he used the Aramaic of Daniel and fourth-century Syriac and Hebrew as the basis for his work.[129]

Middle Aramaic

[edit]During the Late Middle Aramaic period, spanning from 300 BCE to 200 CE, Aramaic diverged into its eastern and western branches. During this time, the nature of various Aramaic dialects began to change. The descendants of Imperial Aramaic ceased to be living languages, and the eastern and western regional dialects started to develop significant new literatures. Unlike many dialects of Old Aramaic, much is known about the vocabulary and grammar of Middle Aramaic.[130]

Eastern Middle Aramaic

[edit]The dialects of Old Eastern Aramaic continued in ancient Assyria, Babylon, and the Achaemenid Empire as written languages using various Aramaic scripts. Eastern Middle Aramaic comprises Classical Mandaic, Hatran, Jewish Babylonian Aramaic dialects, and Classical Syriac.[131]

Syriac Aramaic

[edit]

Syriac Aramaic (also "Classical Syriac") is the literary, liturgical, and often spoken language of Syriac Christianity. It originated in the first century in the region of Osroene, centered in Edessa, but its golden age was the fourth to eighth centuries. This period began with the translation of the Bible into the language: the Peshitta, and the masterful prose and poetry of Ephrem the Syrian. Classical Syriac became the language of Eastern Christianity and missionary activity led to the spread of Syriac from Mesopotamia and Persia, into Central Asia, India, and China.[132][133]

Jewish Babylonian Aramaic

[edit]Jewish Middle Babylonian is the language employed by Jewish writers in Babylonia between the fourth and the eleventh century. It is most commonly identified with the language of the Babylonian Talmud (which was completed in the seventh century) and of post-Talmudic Geonic literature, which are the most important cultural products of Babylonian Judaism. The most important epigraphic sources for the dialect are the hundreds of incantation bowls written in Jewish Babylonian Aramaic.[134]

Mandaic Aramaic

[edit]Classical Mandaic, used as a liturgical language by the Mandaeans of Iraq and Iran, is a sister dialect to Jewish Babylonian Aramaic, though it is both linguistically and culturally distinct. It is the language in which the Mandaeans' gnostic religious literature was composed. It is characterized by a highly phonetic orthography and does not make use of vowel diacritics.[43]

Western Middle Aramaic

[edit]The dialects of Old Western Aramaic continued with Nabataean, Jewish Palestinian (in Hebrew "square script"), Samaritan Aramaic (in the Old Hebrew script), and Christian Palestinian (in Syriac Estrangela script).[135] Of these four, only Jewish Palestinian continued as a written language.[clarification needed]

Samaritan Aramaic

[edit]The Samaritan Aramaic is earliest attested by the documentary tradition of the Samaritans that can be dated back to the fourth century. Its modern pronunciation is based on the form used in the tenth century.[15]

Aramaic in Roman Judea

[edit]

In 135, after the Bar Kokhba revolt, many Jewish leaders, expelled from Jerusalem, moved to Galilee. The Galilean dialect thus rose from obscurity to become the standard among Jews in the west. This dialect was spoken not only in Galilee, but also in the surrounding parts. It is the linguistic setting for the Jerusalem Talmud (completed in the 5th century), Palestinian targumim (Jewish Aramaic versions of scripture), and midrashim (biblical commentaries and teaching). The standard vowel pointing for the Hebrew Bible, the Tiberian system (7th century), was developed by speakers of the Galilean dialect of Jewish Middle Palestinian. Classical Hebrew vocalisation, therefore, in representing the Hebrew of this period, probably reflects the contemporary pronunciation of this Aramaic dialect.[136]

Middle Judaean Aramaic, the descendant of Old Judaean Aramaic, was no longer the dominant dialect, and was used only in southern Judaea (the variant Engedi dialect continued throughout this period). Likewise, Middle East Jordanian Aramaic continued as a minor dialect from Old East Jordanian Aramaic. The inscriptions in the synagogue at Dura-Europos are either in Middle East Jordanian or Middle Judaean.

Christian Aramaic in the Levant

[edit]This was the language of the Christian Melkite (Chalcedonian) community, predominantly of Jewish descent, in Palestine, Transjordan and Sinai[137] from the 5th to the 8th century.[138] As a liturgical language, it was used up to the 13th century. It is also been called "Melkite Aramaic", "Syro-Palestinian" and "Palestinian Syriac".[139] The language itself comes from Old Western Aramaic, but its writing conventions were based on the Aramaic dialect of Edessa, and it was heavily influenced by Greek. For example, the name Jesus, Syriac īšū‘, is written īsūs, a transliteration of the Greek form, in Christian Palestinian.[140]

Modern Aramaic

[edit]

As the Western Aramaic dialects of the Levant have become nearly extinct in non-liturgical usage, the most prolific speakers of Neo-Aramaic languages in the 21st century are Eastern Aramaic speakers, the most numerous being the Central Neo-Aramaic and Northeastern Neo-Aramaic (NENA) speakers of Mesopotamia. This includes speakers of the Assyrian (235,000 speakers) and Chaldean (216,000 speakers) varieties of Suret, and Turoyo (112,000 to 450,000 speakers). Having largely lived in remote areas as insulated communities for over a millennium, the remaining speakers of modern Aramaic dialects, such as the Arameans of the Qalamoun Mountains, Assyrians, Mandaeans and Mizrahi Jews, escaped the linguistic pressures experienced by others during the large-scale language shifts that saw the proliferation of other tongues among those who previously did not speak them, most recently the Arabization of the Middle East and North Africa by Arabs beginning with the early Muslim conquests of the seventh century.[81]

Modern Eastern Aramaic

[edit]

Modern Eastern Aramaic exists in a wide variety of dialects and languages.[141] There is significant difference between the Aramaic spoken by Assyrians, Mizrahi Jews, and Mandaeans, with mutually unintelligible variations within each of these groups.

The Christian varieties of Northeastern Neo-Aramaic (NENA) are often called "Assyrian", "Chaldean" or "Eastern Syriac", and are spoken by the Assyrians in northern Iraq, northeast Syria, southeast Turkey, northwest Iran, and in the diaspora. However, they also have roots in numerous previously unwritten local Aramaic varieties and, in some cases, even contain Akkadian influences. These varieties are not purely the direct descendants of the language of Ephrem the Syrian, which was Classical Syriac.[142]

The Judeo-Aramaic languages are now mostly spoken in Israel, and most are facing extinction. The Jewish varieties that have come from communities that once lived between Lake Urmia and Mosul are not all mutually intelligible. In some places, for example Urmia, Christian Assyrians and Mizrahi Jews speak mutually unintelligible varieties of Northeastern Neo-Aramaic in the same place. In others, the Nineveh Plains around Mosul for example, the varieties of these two ethnicities are similar enough to allow conversation.

Modern Central Neo-Aramaic, being in between Western Neo-Aramaic and Northeastern Neo-Aramaic, is generally represented by Turoyo, the language of the Assyrians/Syriacs of Tur Abdin. A related Neo-Aramaic language, Mlaḥsô, has recently become extinct.[143]

Mandaeans living in the Khuzestan province of Iran and scattered throughout Iraq, speak Neo-Mandaic. It is quite distinct from any other Aramaic variety. Mandaeans number some 50,000–75,000 people, but it is believed Neo-Mandaic may now be spoken fluently by as few as 5,000 people, with other Mandaeans having varying degrees of knowledge.[44]

Modern Western Aramaic

[edit]Very little remains of Western Aramaic. Its only remaining vernacular is Western Neo-Aramaic, which is still spoken in the Aramean villages of Maaloula and Jubb'adin on Syria's side of the Anti-Lebanon Mountains, as well as by some people who migrated from these villages, to Damascus and other larger towns of Syria. Bakh'a was completely destroyed during the Syrian civil war and all the survivors fled to other parts of Syria or to Lebanon.[144] All these speakers of modern Western Aramaic are fluent in Arabic as well.[95] Other Western Aramaic languages, like Jewish Palestinian Aramaic and Samaritan Aramaic, are preserved only in liturgical and literary usage.

Sample texts

[edit]Matthew 2, verses 1–4, in Classical Syriac (Eastern accent), Christian Palestinian Aramaic and Suret (Swadaya):[145][146][147]

| English (KJV): | [1] Now when Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judaea in the days of Herod the king, behold, there came wise men from the east to Jerusalem,

[2] Saying, Where is he that is born King of the Jews? for we have seen his star in the east, and are come to worship him. [3] When Herod the king had heard these things, he was troubled, and all Jerusalem with him. [4] And when he had gathered all the chief priests and scribes of the people together, he demanded of them where Christ should be born. |

|---|---|

| Classical Syriac (Eastern accent): | [1] Ḵaḏ dēyn eṯīleḏ Īšōʕ b-Ḇēṯlḥem d-Īhūḏā b-yawmay Herodes malkā eṯaw mġōšē min maḏnḥā l-Ōrešlem.

[2] W-Āmrīn: Aykaw malkā d-īhūḏāyē d-eṯīleḏ? Ḥzayn gēr kawkḇēh b-maḏnḥā w-eṯayn l-mesgaḏ lēh. [3] Šmaʕ dēyn Herodes malkā w-ettzīʕ w-ḵullāh Ōrešlem ʕammēh. [4] W-ḵanneš ḵulhōn rabbay kāhnē w-sāprē d-ʕammā wa-mšayel-wālhōn d-aykā meṯīleḏ mšīḥā. |

| Christian Palestinian Aramaic: | [1] Ḵaḏ eṯileḏ mōro Yesūs b-Beṯlḥem d-Yuḏō b-yawmay d-Herodes malkō w-hō mġušōya min maḏnḥō eṯaw l-Irušlem.

[2] Ōmrin: Hōn hū deyn d-eṯileḏ? Ḥmaynan ger kawkḇeh b-maḏnḥō w-eṯaynan d-nesguḏ leh. [3] W-ḵaḏ šmaʕ malkō Herodes eṯʕabaḇ w-ḵuloh Irušlem ʕameh. [4] W-ḵaneš ḵulhun rišay koḥnōya w-soprawi d-qahlo wa-hwo mšayel lhun hōn mšiḥō meṯileḏ. |

| Suret (Swadaya): | [1] Min baṯar d-pišleh iliḏe Išo go Beṯlkham d-Ihuḏa b-yomane d-Herodes malka ṯelon mġoše min maḏnkha l-Orešlim.

[2] W-buqrehon: Eykeleh haw d-pišleh iliḏe malka d-ihuḏāye? Sabab khzelan l-kawkhḇeh b-maḏnkha w-telan d-saġdakh eleh. [3] Iman d-šmayeleh Herodes malka aha pišleh šġhiše w-kulaha Orešlim ʔammeh. [4] W-qraeleh kuleh gurane d-kahne w-sapre d-ʔamma w-buqrehmennay eyka bit paiš va iliḏe mšikha. |

Matthew 28, verse 16, in Classical Syriac (Eastern accent), Western Neo-Aramaic, Turoyo and Suret (Swadaya):

| English (KJV): | [16] Then the eleven disciples went away into Galilee, into a mountain where Jesus had appointed them. |

|---|---|

| Classical Syriac (Eastern accent) | [16] Talmīḏē dēyn ḥḏaʕesre āzalū l-Glīlā l-ṭūrā aykā d-waʕad ennūn Īšōʕ. |

| Western Neo-Aramaic: | [16] Bes aḥḥadaʕsar tilmit̲ zallun l-Ġalila l-ṭūra ti amerlun maʕleh Yešūʕ. |

| Turoyo: | [16] Wa-ḥḏaḥsar talmiḏe azzinnewa lu Ġlilo lu ṭūro ayko d-moʕadleh Yešū. |

| Suret (Swadaya): | [16] Ina talmiḏe khadissar azzillun l-Glila l-ṭūra eyka d-bit khwaʔda ʔammeh Išo. |

Phonology

[edit]Each dialect of Aramaic has its own distinctive pronunciation, and it would not be feasible here to go into all these properties. Aramaic has a phonological palette of 25 to 40 distinct phonemes. Some modern Aramaic pronunciations lack the series of "emphatic" consonants, and some have borrowed from the inventories of surrounding languages, particularly Arabic, Azerbaijani, Kurdish, Persian, and Turkish.

Vowels

[edit]| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u |

| Close-mid | e | o |

| Open-mid | ɛ | (ɔ) |

| Open | a | (ɑ) |

As with most Semitic languages, Aramaic can be thought of as having three basic sets of vowels:

- Open a-vowels

- Close front i-vowels

- Close back u-vowels

These vowel groups are relatively stable, but the exact articulation of any individual is most dependent on its consonantal setting.

The open vowel is an open near-front unrounded vowel ("short" a, somewhat like the first vowel in the English "batter", [a]). It usually has a back counterpart ("long" a, like the a in "father", [ɑ], or even tending to the vowel in "caught", [ɔ]), and a front counterpart ("short" e, like the vowel in "head", [ɛ]). There is much correspondence between these vowels between dialects. There is some evidence that Middle Babylonian dialects did not distinguish between the short a and short e. In West Syriac dialects, and possibly Middle Galilean, the long a became the o sound. The open e and back a are often indicated in writing by the use of the letters א "alaph" (a glottal stop) or ה "he" (like the English h).

The close front vowel is the "long" i (like the vowel in "need", [i]). It has a slightly more open counterpart, the "long" e, as in the final vowel of "café" ([e]). Both of these have shorter counterparts, which tend to be pronounced slightly more open. Thus, the short close e corresponds with the open e in some dialects. The close front vowels usually use the consonant י y as a mater lectionis.

The close back vowel is the "long" u (like the vowel in "school", [u]). It has a more open counterpart, the "long" o, like the vowel in "show" ([o]). There are shorter, and thus more open, counterparts to each of these, with the short close o sometimes corresponding with the long open a. The close back vowels often use the consonant ו w to indicate their quality.

Two basic diphthongs exist: an open vowel followed by י y (ay), and an open vowel followed by ו w (aw). These were originally full diphthongs, but many dialects have converted them to e and o respectively.

The so-called "emphatic" consonants (see the next section) cause all vowels to become mid-centralised.

Consonants

[edit]| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Post-alv. / Palatal |

Velar | Uvular / Pharyngeal |

Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | emp. | ||||||||

| Nasal | m | n | |||||||

| Stop | voiceless | p | t | tˤ | k | q | ʔ | ||

| voiced | b | d | ɡ | ||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | θ | s | sˤ | ʃ | x | ħ | h |

| voiced | v | ð | z | ɣ | ʕ | ||||

| Approximant | l | j | w | ||||||

| Trill | r | ||||||||

The various alphabets used for writing Aramaic languages have twenty-two letters (all of which are consonants). Some of these letters, though, can stand for two or three different sounds (usually a stop and a fricative at the same point of articulation). Aramaic classically uses a series of lightly contrasted plosives and fricatives:

- Labial set: פּ\פ p/f and בּ\ב b/v,

- Dental set: תּ\ת t/θ and דּ\ד d/ð,

- Velar set: כּ\כ k/x and גּ\ג ɡ/ɣ.

Each member of a certain pair is written with the same letter of the alphabet in most writing systems (that is, p and f are written with the same letter), and are near allophones.

A distinguishing feature of Aramaic phonology (and that of Semitic languages in general) is the presence of "emphatic" consonants. These are consonants that are pronounced with the root of the tongue retracted, with varying degrees of pharyngealization and velarization. Using their alphabetic names, these emphatics are:

- ח Ḥêṯ, a voiceless pharyngeal fricative, /ħ/,

- ט Ṭêṯ, a pharyngealized t, /tˤ/,

- ע ʽAyin (or ʽE in some dialects), a pharyngealized glottal stop (sometimes considered to be a voiced pharyngeal approximant), [ʕ] or [ʔˤ],

- צ Ṣāḏê, a pharyngealized s, /sˤ/,

- ק Qôp, a voiceless uvular stop, /q/.

Ancient Aramaic may have had a larger series of emphatics, and some Neo-Aramaic languages definitely do. Not all dialects of Aramaic give these consonants their historic values.

Overlapping with the set of emphatics are the "guttural" consonants. They include ח Ḥêṯ and ע ʽAyn from the emphatic set, and add א ʼĀlap̄ (a glottal stop) and ה Hê (as the English "h").

Aramaic classically has a set of four sibilants (ancient Aramaic may have had six):

- ס, שׂ /s/ (as in English "sea"),

- ז /z/ (as in English "zero"),

- שׁ /ʃ/ (as in English "ship"),

- צ /sˤ/ (the emphatic Ṣāḏê listed above).

In addition to these sets, Aramaic has the nasal consonants מ m and נ n, and the approximants ר r (usually an alveolar trill), ל l, י y and ו w.

Historical sound changes

[edit]Six broad features of sound change can be seen as dialect differentials:

- Vowel change occurs almost too frequently to document fully, but is a major distinctive feature of different dialects.

- Plosive/fricative pair reduction. Originally, Aramaic, like Tiberian Hebrew, had fricatives as conditioned allophones for each plosive. In the wake of vowel changes, the distinction eventually became phonemic; still later, it was often lost in certain dialects. For example, Turoyo has mostly lost /p/, using /f/ instead, like Arabic; other dialects (for instance, standard Assyrian Neo-Aramaic) have lost /θ/ and /ð/ and replaced them with /t/ and /d/, as with Modern Hebrew. In most dialects of Modern Syriac, /f/ and /v/ are realized as [w] after a vowel.

- Loss of emphatics. Some dialects have replaced emphatic consonants with non-emphatic counterparts, while those spoken in the Caucasus often have glottalized rather than pharyngealized emphatics.

- Guttural assimilation is the main distinctive feature of Samaritan pronunciation, also found in Samaritan Hebrew: all the gutturals are reduced to a simple glottal stop. Some Modern Aramaic dialects do not pronounce h in all words (the third person masculine pronoun hu becomes ow).

- Proto-Semitic */θ/ */ð/ are reflected in Aramaic as */t/, */d/, whereas they became sibilants in Hebrew (the number three is שלוש šālôš in Hebrew but תלת tlāṯ in Aramaic, the word gold is זהב zahav[148] in Hebrew but דהב dehav[149] in Aramaic). Dental/sibilant shifts are still happening in the modern dialects.

- New phonetic inventory. Modern dialects have borrowed sounds from the dominant surrounding languages. The most frequent borrowings are [ʒ] (as the first consonant in "azure"), [d͡ʒ] (as in "jam"), and [t͡ʃ] (as in "church"). The Syriac alphabet has been adapted for writing these new sounds.

Grammar

[edit]As in other Semitic languages, Aramaic morphology (the way words are formed) is based on the consonantal root. The root generally consists of two or three consonants and has a basic meaning, for example, כת״ב k-t-b has the meaning of 'writing'. This is then modified by the addition of vowels and other consonants to create different nuances of the basic meaning:

- כתבה kṯāḇâ, handwriting, inscription, script, book.

- כתבי kṯāḇê, books, the Scriptures.

- כתובה kāṯûḇâ, secretary, scribe.

- כתבת kiṯḇeṯ, I wrote.

- אכתב 'eḵtûḇ, I shall write.

Nouns and adjectives

[edit]Aramaic nouns and adjectives are inflected to show gender, number and state.

Aramaic has two grammatical genders: masculine and feminine. The feminine absolute singular is often marked by the ending ה- -â.

Nouns can be either singular or plural, but an additional "dual" number exists for nouns that usually come in pairs. The dual number gradually disappeared from Aramaic over time and has little influence in Middle and Modern Aramaic.

Aramaic nouns and adjectives can exist in one of three states. To a certain extent, these states correspond to the role of articles and cases in the Indo-European languages:

- The absolute state is the basic form of a noun. In early forms of Aramaic, the absolute state expresses indefiniteness, comparable to the English indefinite article a(n) (for example, כתבה kṯāḇâ, "a handwriting"), and can be used in most syntactic roles. However, by the Middle Aramaic period, its use for nouns (but not adjectives) had been widely replaced by the emphatic state.

- The construct state is a form of the noun used to make possessive constructions (for example, כתבת מלכתא kṯāḇat malkṯâ, "the handwriting of the queen"). In the masculine singular, the form of the construct is often the same as the absolute, but it may undergo vowel reduction in longer words. The feminine construct and masculine construct plural are marked by suffixes. Unlike a genitive case, which marks the possessor, the construct state is marked on the possessed. This is mainly due to Aramaic word order: possessed[const.] possessor[abs./emph.] are treated as a speech unit, with the first unit (possessed) employing the construct state to link it to the following word. In Middle Aramaic, the use of the construct state for all but stock phrases (like בר נשא bar nāšâ, "son of man") begins to disappear.

- The emphatic or determined state is an extended form of the noun that functions similarly to the definite article. It is marked with a suffix (for example, כתבתא kṯāḇtâ, "the handwriting"). Although its original grammatical function seems to have been to mark definiteness, it is used already in Imperial Aramaic to mark all important nouns, even if they should be considered technically indefinite. This practice developed to the extent that the absolute state became extraordinarily rare in later varieties of Aramaic.

Whereas other Northwest Semitic languages, like Hebrew, have the absolute and construct states, the emphatic/determined state is a unique feature to Aramaic. Case endings, as in Ugaritic, probably existed in a very early stage of the language, and glimpses of them can be seen in a few compound proper names. However, as most of those cases were expressed by short final vowels, they were never written, and the few characteristic long vowels of the masculine plural accusative and genitive are not clearly evidenced in inscriptions. Often, the direct object is marked by a prefixed -ל l- (the preposition "to") if it is definite.

Adjectives agree with their nouns in number and gender but agree in state only if used attributively. Predicative adjectives are in the absolute state regardless of the state of their noun (a copula may or may not be written). Thus, an attributive adjective to an emphatic noun, as in the phrase "the good king", is written also in the emphatic state מלכא טבא malkâ ṭāḇâ – king[emph.] good[emph.]. In comparison, the predicative adjective, as in the phrase "the king is good", is written in the absolute state מלכא טב malkâ ṭāḇ – king[emph.] good[abs.].

| "good" | masc. sg. | fem. sg. | masc. pl. | fem. pl. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| abs. | טב ṭāḇ | טבה ṭāḇâ | טבין ṭāḇîn | טבן ṭāḇān |

| const. | טבת ṭāḇaṯ | טבי ṭāḇê | טבת ṭāḇāṯ | |

| det./emph. | טבא ṭāḇâ | טבתא ṭāḇtâ | טביא ṭāḇayyâ | טבתא ṭāḇāṯâ |

The final א- -â in a number of these suffixes is written with the letter aleph. However, some Jewish Aramaic texts employ the letter he for the feminine absolute singular. Likewise, some Jewish Aramaic texts employ the Hebrew masculine absolute singular suffix ים- -îm instead of ין- -în. The masculine determined plural suffix, יא- -ayyâ, has an alternative version, -ê. The alternative is sometimes called the "gentilic plural" for its prominent use in ethnonyms (יהודיא yəhûḏāyê, 'the Jews', for example). This alternative plural is written with the letter aleph, and came to be the only plural for nouns and adjectives of this type in Syriac and some other varieties of Aramaic. The masculine construct plural, -ê, is written with yodh. In Syriac and some other variants this ending is diphthongized to -ai.

Possessive phrases in Aramaic can either be made with the construct state or by linking two nouns with the relative particle -[ד[י d[î]-. As the use of the construct state almost disappears from the Middle Aramaic period on, the latter method became the main way of making possessive phrases.

For example, the various forms of possessive phrases (for "the handwriting of the queen") are:

- כתבת מלכתא kṯāḇaṯ malkṯâ – the oldest construction, also known as סמיכות səmîḵûṯ : the possessed object (כתבה kṯābâ, "handwriting") is in the construct state (כתבת kṯāḇaṯ); the possessor (מלכה malkâ, "queen") is in the emphatic state (מלכתא malkṯâ)

- כתבתא דמלכתא kṯāḇtâ d(î)-malkṯâ – both words are in the emphatic state and the relative particle -[ד[י d[î]- is used to mark the relationship

- כתבתה דמלכתא kṯāḇtāh d(î)-malkṯâ – both words are in the emphatic state, and the relative particle is used, but the possessed is given an anticipatory, pronominal ending (כתבתה kṯāḇtā-h, "handwriting-her"; literally, "her writing, that (of) the queen").

In Modern Aramaic, the last form is by far the most common. In Biblical Aramaic, the last form is virtually absent.

Verbs

[edit]The Aramaic verb has gradually evolved in time and place, varying between varieties of the language. Verb forms are marked for person (first, second or third), number (singular or plural), gender (masculine or feminine), tense (perfect or imperfect), mood (indicative, imperative, jussive, or infinitive), and voice (active, reflexive, or passive). Aramaic also employs a system of conjugations, or verbal stems, to mark intensive and extensive developments in the lexical meaning of verbs.

Aspectual tense

[edit]Aramaic has two proper tenses: perfect and imperfect. These were originally aspectual, but developed into something more like a preterite and future. The perfect is unmarked, while the imperfect uses various preformatives that vary according to person, number and gender. In both tenses the third-person singular masculine is the unmarked form from which others are derived by addition of afformatives (and preformatives in the imperfect). In the chart below (on the root כת״ב K-T-B, meaning "to write"), the first form given is the usual form in Imperial Aramaic, while the second is Classical Syriac.

| Person & gender | Perfect | Imperfect | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| 3rd m. | כתב kəṯaḇ ↔ kəṯaḇ | כתבו ↔ כתב(ו)\כתבון kəṯaḇû ↔ kəṯaḇ(w)/kəṯabbûn | יכתוב ↔ נכתוב yiḵtuḇ ↔ neḵtoḇ | יכתבון ↔ נכתבון yiḵtəḇûn ↔ neḵtəḇûn |

| 3rd f. | כתבת kiṯbaṯ ↔ keṯbaṯ | כתבת ↔ כתב(י)\כתבן kəṯaḇâ ↔ kəṯaḇ(y)/kəṯabbên | תכתב tiḵtuḇ ↔ teḵtoḇ | יכתבן ↔ נכתבן yiḵtəḇān ↔ neḵtəḇān |

| 2nd m. | כתבת kəṯaḇt ↔ kəṯaḇt | כתבתון kəṯaḇtûn ↔ kəṯaḇton | תכתב tiḵtuḇ ↔ teḵtoḇ | תכתבון tiḵtəḇûn ↔ teḵtəḇûn |

| 2nd f. | (כתבתי ↔ כתבת(י kəṯaḇtî ↔ kəṯaḇt(y) | כתבתן kəṯaḇtēn ↔ kəṯaḇtên | תכתבין tiḵtuḇîn ↔ teḵtuḇîn | תכתבן tiḵtəḇān ↔ teḵtəḇān |

| 1st m./f. | כתבת kiṯḇēṯ ↔ keṯḇeṯ | כתבנא ↔ כתבן kəṯaḇnâ ↔ kəṯaḇn | אכתב eḵtuḇ ↔ eḵtoḇ | נכתב niḵtuḇ ↔ neḵtoḇ |

Conjugations or verbal stems

[edit]Like other Semitic languages, Aramaic employs a number of derived verb stems, to extend the lexical coverage of verbs. The basic form of the verb is called the ground stem, or G-stem. Following the tradition of mediaeval Arabic grammarians, it is more often called the Pə‘al פעל (also written Pe‘al), using the form of the Semitic root פע״ל P-‘-L, meaning "to do". This stem carries the basic lexical meaning of the verb.

By doubling of the second radical, or root letter, the D-stem or פעל Pa‘‘el is formed. This is often an intensive development of the basic lexical meaning. For example, qəṭal means "he killed", whereas qaṭṭel means "he slew". The precise relationship in meaning between the two stems differs for every verb.

A preformative, which can be -ה ha-, -א a-, or -ש ša-, creates the C-stem or variously the Hap̄‘el, Ap̄‘el or Šap̄‘el (also spelt הפעל Haph‘el, אפעל Aph‘el, and שפעל Shaph‘el). This is often an extensive or causative development of the basic lexical meaning. For example, טעה ṭə‘â means "he went astray", whereas אטעי aṭ‘î means "he deceived". The Šap̄‘el שפעל is the least common variant of the C-stem. Because this variant is standard in Akkadian, it is possible that its use in Aramaic represents loanwords from that language. The difference between the variants הפעל Hap̄‘el and אפעל Ap̄‘el appears to be the gradual dropping of the initial ה h sound in later Old Aramaic. This is noted by the respelling of the older he preformative with א aleph.

These three conjugations are supplemented with three further derived stems, produced by the preformative -הת hiṯ- or -את eṯ-. The loss of the initial ה h sound occurs similarly to that in the form above. These three derived stems are the Gt-stem, התפעל Hiṯpə‘el or אתפעל Eṯpə‘el (also written Hithpe‘el or Ethpe‘el), the Dt-stem, התפעּל Hiṯpa‘‘al or אתפעּל Eṯpa‘‘al (also written Hithpa‘‘al or Ethpa‘‘al), and the Ct-stem, התהפעל Hiṯhap̄‘al, אתּפעל Ettap̄‘al, השתפעל Hištap̄‘al or אשתפעל Eštap̄‘al (also written Hithhaph‘al, Ettaph‘al, Hishtaph‘al, or Eshtaph‘al). Their meaning is usually reflexive, but later became passive. However, as with other stems, actual meaning differs from verb to verb.

Not all verbs use all of these conjugations, and, in some, the G-stem is not used. In the chart below (on the root כת״ב K-T-B, meaning "to write"), the first form given is the usual form in Imperial Aramaic, while the second is Classical Syriac.

| Stem | Perfect active | Imperfect active | Perfect passive | Imperfect passive |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| פעל Pə‘al (G-stem) | כתב kəṯaḇ ↔ kəṯaḇ | יכתב ↔ נכתב yiḵtuḇ ↔ neḵtoḇ | כתיב kəṯîḇ | |

| התפעל\אתפעל Hiṯpə‘ēl/Eṯpə‘el (Gt-stem) | התכתב ↔ אתכתב hiṯkəṯēḇ ↔ eṯkəṯeḇ | יתכתב ↔ נתכתב yiṯkəṯēḇ ↔ neṯkəṯeḇ | ||

| פעּל Pa‘‘ēl/Pa‘‘el (D-stem) | כתּב kattēḇ ↔ katteḇ | יכתּב ↔ נכתּב yəḵattēḇ ↔ nəkatteḇ | כֻתּב kuttaḇ | |

| התפעל\אתפעל Hiṯpa‘‘al/Eṯpa‘‘al (Dt-stem) | התכתּב ↔ אתכתּב hiṯkəttēḇ ↔ eṯkətteḇ | יתכתּב ↔ נתכתּב yiṯkəttēḇ ↔ neṯkətteḇ | ||

| הפעל\אפעל Hap̄‘ēl/Ap̄‘el (C-stem) | הכתב ↔ אכתב haḵtēḇ ↔ aḵteḇ | יהכתב↔ נכתב yəhaḵtēḇ ↔ naḵteḇ | הֻכתב huḵtaḇ | |

| התהפעל\אתּפעל Hiṯhap̄‘al/Ettap̄‘al (Ct-stem) | התהכתב ↔ אתּכתב hiṯhaḵtaḇ ↔ ettaḵtaḇ | יתהכתב ↔ נתּכתב yiṯhaḵtaḇ ↔ nettaḵtaḇ |

In Imperial Aramaic, the participle began to be used for a historical present. Perhaps under influence from other languages, Middle Aramaic developed a system of composite tenses (combinations of forms of the verb with pronouns or an auxiliary verb), allowing for narrative that is more vivid. Aramaic syntax usually follows the order verb–subject–object (VSO). Imperial (Persian) Aramaic, however, tended to follow a S-O-V pattern (similar to Akkadian), which was the result of Persian syntactic influence.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Kozah, Mario; Abu-Husayn, Abdulrahim; Al-Murikhi, Saif Shaheen; Al Thani, Haya (9 December 2014). The Syriac Writers of Qatar in the Seventh Century. Gorgias Press. p. 298. ISBN 9781463236649.

The Syriac writers of Qatar themselves produced some of the best and most sophisticated writing to be found in all Syriac literature of the seventh century, but they have not received the scholarly attention that they deserve in the last half century. This volume seeks to redress this underdevelopment by setting the standard for further research in the sub-field of Beth Qatraye studies.

- ^ Huehnergard, J., "What is Aramaic?." Aram 7 (1995): 281

- ^ Thompson, Andrew David (31 October 2019). Christianity in Oman. Springer. p. 49. ISBN 9783030303983.

The Persian location and character of the Metropolitan proved to be a source of friction between the Syriac-speaking Christians of Beth Qatraye who naturally looked to their co-linguists back in Mesopotamia.

- ^ Raheb, Mitri; Lamport, Mark A. (15 December 2020). The Rowman & Littlefield Handbook of Christianity in the Middle East. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 134. ISBN 9781538124185.

He was born in the region of Beth Qatraye in Eastern Arabia, a mixed Syriac- and Arabic Speaking region...

- ^ a b Brock 1989, pp. 11–23.

- ^ Huehnergard, John; Rubin, Aaron D. (2011). "Phyla and Waves: Models of Classification of the Semitic Languages". In Weninger, Stefan (ed.). The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. pp. 259–278. ISBN 978-3-11-018613-0.

- ^ Gzella 2021, pp. 4–5: "The overarching concept of Aramaic, strictly a historical-linguistic abstraction, is made more concrete by various terms for the various Aramaic languages (or dialects, where we are mainly dealing with regional vernaculars without a written tradition; the neutral term variety includes both categories). ... Or scholars use the same terms to refer to different historical periods, as with "Old Aramaic" or "Imperial Aramaic." Others still are just misleading, such as "Modern Syriac" for the modern spoken languages, which do not directly descend from Syriac. When discussing what a certain word or phrase is "in Aramaic" then, we always have to specify which period, region, or culture is meant unlike Classical Latin, for instance. ... For the most part, Aramaic is thus studied as a crucial but subservient element in several well-established, mainly philological and historical disciplines and social sciences. Even in the academic world, only few people see any inherent value that transcends the disciplinary boundaries in this language family."[excessive quote]

- ^ Van Rompay, Lucas (2011). "Aramaic". In Brock, Sebastian P.; Butts, Aaron M.; Kiraz, George A.; Van Rompay, Lucas (eds.). Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage (Electronic Edition, Beth Mardutho, 2018 ed.). Gorgias Press. ISBN 978-1-59333-714-8.

Aramaic itself consists of a great number of language forms (and indeed languages), spoken and written in many different scripts over a period of 3000 years.

- ^ Aufrecht 2001, p. 145, "The Aramaic Language originated in ancient Syria at the end of the Late Bronze Age (c. 1500–1200 B.C.), is one of the oldest continually spoken languages in the world.".

- ^

- Schami, Rafik (25 July 2011). Märchen aus Malula (in German). Carl Hanser. p. 151. ISBN 9783446239005.

Ich kenne das Dorf nicht, doch gehört habe ich davon. Was ist mit Malula?‹ fragte der festgehaltene Derwisch. >Das letzte Dorf der Aramäer< lachte einer der…

- Matras, Yaron; Sakel, Jeanette (2007). Grammatical Borrowing in Cross-Linguistic Perspective. De Gruyter. p. 185. doi:10.1515/9783110199192. ISBN 9783110199192.

The fact that nearly all Arabic loans in Ma'lula originate from the period before the change from the rural dialect to the city dialect of Damascus shows that the contact between the Aramaeans and the Arabs was intimate…

- Labidi, Emna (2022). Untersuchungen zum Spracherwerb zweisprachiger Kinder im Aramäerdorf Dschubbadin (Syrien) (in German). LIT. p. 133. ISBN 9783643152619.

Aramäer von Ǧubbˁadīn

- Arnold, Werner; Behnstedt, P. (1993). Arabisch-aramäische Sprachbeziehungen im Qalamūn (Syrien) (in German). Harassowitz. p. 42. ISBN 9783447033268.

Die arabischen Dialekte der Aramäer

- Arnold, Werner; Behnstedt, P. (1993). Arabisch-aramäische Sprachbeziehungen im Qalamūn (Syrien) (in German). Harassowitz. p. 5. ISBN 9783447033268.

Die Kontakte zwischen den drei Aramäer-dörfern sind nicht besonders stark.

- Arnold, Werner (2006). Lehrbuch des Neuwestaramäischen (in German). Harrassowitz. p. 133. ISBN 9783447053136.

Aramäern in Ma'lūla

- Arnold, Werner (2006). Lehrbuch des Neuwestaramäischen (in German). Harrassowitz. p. 15. ISBN 9783447053136.

Viele Aramäer arbeiten heute in Damaskus, Beirut oder in den Golfstaaten und verbringen nur die Sommermonate im Dorf.

- Schami, Rafik (25 July 2011). Märchen aus Malula (in German). Carl Hanser. p. 151. ISBN 9783446239005.

- ^

- ^ Gzella 2021, p. 222: "Despite their divergent creeds and confessional affiliations, they retained their own West or East Syriac ritual prayers and liturgical formulae; on the one hand, there are the West Syriac Orthodox and Syriac Catholics...and also to a lesser degree the similarly Catholic Maronites (where Arabic is increasingly taking over the function of Syriac); on the other hand, there is the Assyrian "Church of the East," which stems from the East Syriac tradition, and...the Chaldean Catholic Church. Additionally, some of the many Christian churches of India belong to the Syriac tradition."

- ^ Greenfield 1995.

- ^ Berlin 2011.

- ^ a b Tal 2012, p. 619–28.

- ^ Burtea 2012, pp. 670–685.

- ^ Naby 2004, pp. 197–203.

- ^ Macuch 1990, pp. 214–223.

- ^ Coghill 2007, pp. 115–122.

- ^ Lipiński 2001, p. 64.

- ^ Gzella 2015, pp. 17–22.

- ^ Daniels 1996, pp. 499–514.

- ^ Beyer 1986, p. 56.

- ^ Gzella 2015, p. 56

- ^ Myers, Allen C., ed. (1987). "Aramaic". The Eerdmans Bible Dictionary. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans. p. 72. ISBN 0-8028-2402-1.

It is generally agreed that Aramaic was the common language of Israel in the first century AD. Jesus and his disciples spoke the Galilean dialect, which was distinguished from that of Jerusalem (Matt. 26:73)

- ^ "Aramaic language". Encyclopædia Britannica. 10 April 2024. Retrieved 10 May 2024.

- ^ a b Lipiński 2000.

- ^ Khan 2007, pp. 95–114.

- ^ a b Gzella 2015.

- ^ a b Folmer 2012, pp. 587–98.

- ^ a b Bae 2004, pp. 1–20.

- ^ Green 1992, p. 45.

- ^ Kitchen 1965, pp. 31–79.

- ^ Rosenthal 2006.

- ^ Gzella 2015, pp. 304–10.

- ^ Ruzer 2014, pp. 182–205.

- ^ Buth 2014, pp. 395–421.

- ^ Gzella 2015, p. 237.

- ^ "Sanhedrin 38b". www.sefaria.org.

- ^ Beyer 1986, pp. 38–43.

- ^ Casey 1999, pp. 83–93.

- ^ Turek, Przemysław (2011-11-05). "Syriac Heritage of the Saint Thomas Christians: Language and Liturgical Tradition Saint Thomas Christians – origins, language and liturgy". Orientalia Christiana Cracoviensia. 3: 115–130. doi:10.15633/ochc.1038. ISSN 2081-1330.

- ^ a b Burtea 2012, pp. 670–85.

- ^ a b c d Häberl 2012, pp. 725–37.

- ^ Heinrichs 1990, pp. xi–xv.

- ^ Beyer 1986, p. 53.

- ^ "Did you know". Surayt-Aramaic Online Project. Free University of Berlin.

- ^ Duntsov, Alexey; Häberl, Charles; Loesov, Sergey (2022). "A Modern Western Aramaic Account of the Syrian Civil War". WORD. 68 (4): 359–394. doi:10.1080/00437956.2022.2084663.

- ^ Brock, An Introduction to Syriac Studies Archived 2013-05-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kopp, Ulrich Friedrich [in German] (1821). "Semitische Paläographie: Aramäische ältere Schrift". Bilder und Schriften der Vorzeit. pp. 226–27.

- ^ Caputo, C.; Lougovaya, J. (2020). Using Ostraca in the Ancient World: New Discoveries and Methodologies. Materiale Textkulturen. De Gruyter. p. 147. ISBN 978-3-11-071290-2.

The earliest of the Aramaic finds known to us is the so-called "Carpentras stele"...

- ^ Schmidt, Nathaniel (1923). "Early Oriental Studies in Europe and the Work of the American Oriental Society, 1842–1922". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 43: 1–14. doi:10.2307/593293. JSTOR 593293.

Hilliger first saw clearly the relation of the so-called Chaldee, Syriac, and Samaritan (1679)

- ^ Johann Wilhelm Hilliger (1679). Summarium Lingvæ Aramææ, i.e. Chaldæo-Syro-Samaritanæ: olim in Academia Wittebergensi orientalium lingvarum consecraneis, parietes intra privatos, prælectum & nunc ... publico bono commodatum. Sumtibus hæred. D. Tobiæ Mevii & Elerti Schumacheri, per Matthæum Henckelium.

[Partial English translation]: "The Aramaic language name comes from its gentile founder, Aram (Gen 10:22), in the same manner as the Slavic languages Bohemian, Polish, Vandal etc. Multiple dialects are Chaldean, Syrian, Samaritan."; Latin Original: Linguae Aramaeae nomen à gentis conditore, Aramo nimirum (Gen. X 22) desumptum est, & complectitur, perinde ut Lingua Sclavonica, Bohemican, Polonican, Vandalicam &c. Dialectos plures, ceu sunt: Chaldaica, Syriaca, Samaritana.

- ^ Lemaire, André (2021-05-25). "A History of Northwest Semitic Epigraphy". An Eye for Form. Penn State University Press. p. 5. doi:10.1515/9781575068879-007 (inactive 11 July 2025). ISBN 9781575068879. Retrieved 2022-10-05 – via De Gruyter.

In his Bilder und Schriften der Vorzeit, Ulrich Friedrich Kopp (1819–21) established the basis of the paleographical development of the Northwest Semitic scripts...