Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

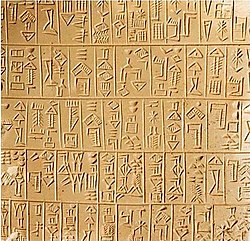

Cuneiform

View on WikipediaThis article should specify the language of its non-English content using {{lang}} or {{langx}}, {{transliteration}} for transliterated languages, and {{IPA}} for phonetic transcriptions, with an appropriate ISO 639 code. Wikipedia's multilingual support templates may also be used. (March 2024) |

| Cuneiform | |

|---|---|

A trilingual cuneiform inscription of Xerxes I at Van Fortress in Turkey, an Achaemenid royal inscription written in Old Persian, Elamite and Babylonian forms of cuneiform | |

| Script type | and syllabary |

Period | c. 2900 BC – c. 100 AD |

| Direction | Left-to-right |

| Region | Sumer |

| Languages | Sumerian, Akkadian, Eblaite, Elamite, Hittite, Hurrian, Luwian, Urartian, Palaic, Aramaic, Old Persian, Ugaritic |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | |

Child systems | None; influenced the shape of Ugaritic and Old Persian glyphs |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Xsux (020), Cuneiform, Sumero-Akkadian |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Cuneiform |

| |

Cuneiform[note 1] is a logo-syllabic writing system that was used to write several languages of the ancient Near East.[3] The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era.[4] Cuneiform scripts are marked by and named for the characteristic wedge-shaped impressions (Latin: cuneus) which form their signs. Cuneiform is the earliest known writing system[5][6] and was originally developed to write the Sumerian language of southern Mesopotamia (modern Iraq).

Over the course of its history, cuneiform was adapted to write a number of languages in addition to Sumerian. Akkadian texts are attested from the 24th century BC onward and make up the bulk of the cuneiform record.[4][7] Akkadian cuneiform was itself adapted to write the Hittite language in the early 2nd millennium BC.[4][8] The other languages with significant cuneiform corpora are Eblaite, Elamite, Hurrian, Luwian, and Urartian. The Old Persian and Ugaritic alphabets feature cuneiform-style signs; however, they are unrelated to the cuneiform logo-syllabary proper. The latest known cuneiform tablet, an astronomical almanac from Uruk, dates to AD 79/80.[9]

Cuneiform was rediscovered in modern times in the early 17th century with the publication of the trilingual Achaemenid royal inscriptions at Persepolis; these were first deciphered in the early 19th century. The modern study of cuneiform belongs to the ambiguously named[10] field of Assyriology, as the earliest excavations of cuneiform libraries during the mid-19th century were in the area of ancient Assyria.[5] An estimated half a million tablets are held in museums across the world, but comparatively few of these are published. The largest collections belong to the British Museum (approximately 130,000 tablets), the Vorderasiatisches Museum Berlin, the Louvre, the Istanbul Archaeology Museums, the National Museum of Iraq, the Yale Babylonian Collection (approximately 40,000 tablets), and the Penn Museum.[11][12]

History

[edit]

Writing began after pottery was invented, during the Neolithic when clay tokens were used to record specific amounts of livestock or commodities.[14] These tokens were initially impressed on the surface of round clay envelopes (clay bullae) and then stored in them.[14] The tokens were then progressively replaced by flat tablets, on which signs were recorded with a stylus. Writing is first recorded in Uruk, at the end of the 4th millennium BC, and soon after in various parts of the Near-East.[14]

An ancient Mesopotamian poem gives the first known story of the invention of writing:

Because the messenger's mouth was heavy and he couldn't repeat [the message], the Lord of Kulaba patted some clay and put words on it, like a tablet. Until then, there had been no putting words on clay.

— Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta, c. 1800 BC[5]

The cuneiform writing system was in use for more than three millennia, through several stages of development, from the 31st century BC down to the second century AD.[15] The latest firmly dateable tablet, from Uruk, dates to 79/80 AD.[9] Ultimately, it was completely replaced by alphabetic writing, in the general sense, in the course of the Roman era, and there are no cuneiform systems in current use. It had to be deciphered as a completely unknown writing system in 19th-century Assyriology. It was successfully deciphered by 1857.

|

The cuneiform script changed considerably over more than 2,000 years. The image below shows the development of the sign SAĜ "head" (Borger nr. 184, U+12295 𒊕).  Stages:

|

In recent years a contrarian view has arisen on the tokens being the precursor of writing.[16]

Sumerian pictographs (c. 3300 BC)

[edit]

The cuneiform script was developed from pictographic proto-writing in the late 4th millennium BC, stemming from the Near Eastern token system used for accounting. The meaning and usage of these tokens is still a matter of debate.[17] These tokens were in use from the 9th millennium BC and remained in occasional use into the late 2nd millennium BC.[18] Early tokens with pictographic shapes of animals, associated with numbers, were discovered in Tell Brak, and date to the mid-4th millennium BC.[19] It has been suggested that the token shapes were the original basis for some of the Sumerian pictographs.[20]

Mesopotamia's "proto-literate" period spans roughly the 35th to 32nd centuries BC. The first unequivocal written documents start with the Uruk IV period, from c. 3300 BC, followed by tablets found in Uruk III, Jemdet Nasr, Early Dynastic I Ur and Susa (in Proto-Elamite) dating to the period until c. 2900 BC.[21]

Originally, pictographs were either drawn on clay tablets in vertical columns with a sharpened reed stylus or incised in stone. This early style lacked the characteristic wedge shape of the strokes.[19] Most Proto-Cuneiform records from this period were of an accounting nature.[22] The proto-cuneiform sign list has grown, as new texts are discovered, and shrunk, as variant signs are combined. The current sign list is 705 elements long with 42 being numeric and four considered pre-proto-Elamite.[23][24][25]

Certain signs to indicate names of gods, countries, cities, vessels, birds, trees, etc., are known as determinatives and were the Sumerian signs of the terms in question, added as a guide for the reader. Proper names continued to be usually written in purely "logographic" fashion.

Archaic cuneiform (c. 2900 BC)

[edit]

The first inscribed tablets were purely pictographic, which makes it technically difficult to determine which language they represent. Different languages have been proposed, though usually Sumerian is assumed.[27] Later tablets dating after c. 2900 BC start to use syllabic elements, which clearly show a language structure typical of the agglutinative Sumerian language.[28] The first tablets using syllabic elements date to the Early Dynastic I–II periods c. 2800 BC, and they are agreed to be clearly in Sumerian.[29]

About 2800 BC some pictographic elements started to be used for their phonetic syllabic value,[30] permitting the recording of abstract ideas and personal names.[29] Many pictographs began to lose their original function, and a given sign could have various meanings depending on context. The sign inventory was reduced from some 1,500 signs to some 600 signs, and writing became increasingly phonological. Determinative signs were re-introduced to avoid ambiguity. Cuneiform writing proper thus arises from the more primitive system of pictographs at about this time, which historians label the Early Bronze Age II epoch.

The earliest known Sumerian king whose name appears on contemporary cuneiform tablets is Enmebaragesi of Kish (fl. c. 2600 BC).[31] Surviving records became less fragmentary for following reigns, and by the arrival of Sargon it had become standard practice for each major city-state to date documents by year-names, commemorating the exploits of its king.

-

A proto-cuneiform tablet, end of the 4th millennium BC

-

A proto-cuneiform tablet, Jemdet Nasr period, c. 3100–2900 BC. A dog on a leash is visible in the background of the lower panel.[32]

-

The Blau Monuments combine proto-cuneiform characters and illustrations, 3100–2700 BC. British Museum.

Cuneiforms and hieroglyphs

[edit]Geoffrey Sampson stated that Egyptian hieroglyphs "came into existence a little after Sumerian script, and, probably, [were] invented under the influence of the latter",[5] and that it is "probable that the general idea of expressing words of a language in writing was brought to Egypt from Sumerian Mesopotamia".[5][33] There are many instances of Egypt-Mesopotamia relations at the time of the invention of writing, and standard reconstructions of the development of writing generally place the development of the Sumerian proto-cuneiform script before the development of Egyptian hieroglyphs, with the suggestion the former influenced the latter.[34] Given the lack of direct evidence for the transfer of writing, "no definitive determination has been made as to the origin of hieroglyphics in ancient Egypt".[5]

Early Dynastic cuneiform (c. 2500 BC)

[edit]

Early cuneiform inscriptions were made by using a pointed stylus, sometimes called "linear cuneiform".[5] Many of the early dynastic inscriptions, particularly those made on stone, continued to use the linear style as late as c. 2000 BC.[5]

In the mid-3rd millennium BC, a new wedge-tipped stylus was introduced which was pushed into the clay, producing wedge-shaped cuneiform. This development made writing quicker and easier, especially when writing on soft clay. By adjusting the relative position of the stylus to the tablet, the writer could use a single tool to make a variety of impressions. For numbers, a round-tipped stylus was initially used, until the wedge-tipped stylus was generalized. The direction of writing was from top-to-bottom and right-to-left. Cuneiform clay tablets could be fired in kilns to bake them hard, and so provide a permanent record, or they could be left moist and recycled if permanence was not needed. Most surviving cuneiform tablets were of the latter kind, accidentally preserved when fires destroyed the tablets' storage place and effectively baked them, unintentionally ensuring their longevity.[5]

The script was widely used on commemorative stelae and carved reliefs to record the achievements of the ruler in whose honor the monument had been erected. The spoken language included many homophones and near-homophones, and in the beginning, similar-sounding words such as "life" [til] and "arrow" [ti] were written with the same symbol (𒋾). As a result, many signs gradually changed from being logograms to also functioning as syllabograms, so that for example, the sign for the word "arrow" would become the sign for the sound "ti".[35]

Syllabograms were used in Sumerian writing especially to express grammatical elements, and their use was further developed and modified in the writing of the Akkadian language to express its sounds.[35] Often, words that had a similar meaning but very different sounds were written with the same symbol. For instance the Sumerian words 'tooth' [zu], 'mouth' [ka] and 'voice' [gu] were all written with the original pictogram for mouth (𒅗).

Words that sounded alike would have different signs; for instance, the syllable [ɡu] had fourteen different symbols.

The inventory of signs was expanded by the combination of existing signs into compound signs. They could either derive their meaning from a combination of the meanings of both original signs (e.g. 𒅗 ka 'mouth' and 𒀀 a 'water' were combined to form the sign for 𒅘 nag̃ 'drink', formally KA×A; cf. Chinese compound ideographs), or one sign could suggest the meaning and the other the pronunciation (e.g. 𒅗 ka 'mouth' was combined with the sign 𒉣 nun 'prince' to express the word 𒅻 nundum, meaning 'lip', formally KA×NUN; cf. Chinese phono-semantic compounds).[35]

Another way of expressing words that had no sign of their own was by so-called 'Diri compounds' – sign sequences that have, in combination, a reading different from the sum of the individual constituent signs (for example, the compound IGI.A (𒅆𒀀) – "eye" + "water" – has the reading imhur, meaning "foam").[35]

Several symbols had too many meanings to permit clarity. Therefore, symbols were put together to indicate both the sound and the meaning of a symbol. For instance, the word 'raven' (UGA) had the same logogram (𒉀) as the word 'soap' (NAGA), the name of a city (EREŠ), and the patron goddess of Eresh (NISABA). To disambiguate and identify the word more precisely, two phonetic complements were added – Ú (𒌑) for the syllable [u] in front of the symbol and GA (𒂵) for the syllable [ga] behind. Finally, the symbol for 'bird', MUŠEN (𒄷) was added to ensure proper interpretation. As a result, the whole word could be spelt 𒌑𒉀𒂵𒄷, i.e. Ú.NAGA.GAmušen (among the many variant spellings that the word could have).

For unknown reasons, cuneiform pictographs, until then written vertically, were rotated 90° counterclockwise, in effect putting them on their side. This change first occurred slightly before the Akkadian period, at the time of the Uruk ruler Lugalzagesi (r. c. 2294–2270 BC).[26][5] The vertical style remained for monumental purposes on stone stelas until the middle of the 2nd millennium.[5]

Written Sumerian was used as a scribal language until the 1st century AD. The spoken language died out between c. 2100 and 1700 BC.

Sumero-Akkadian cuneiform

[edit](c. 2200 BC)

The archaic cuneiform script was adopted by the Akkadian Empire from the 23rd century BC (short chronology). The Akkadian language being East Semitic, its structure was completely different from Sumerian .[19] The Akkadians found a practical solution in writing their language phonetically, using the corresponding Sumerian phonetic signs.[19] Still, many of the Sumerian characters were retained for their logographic value as well: for example the character for "sheep" was retained, but was now pronounced immerum, rather than the Sumerian udu.[19] Such retained individual signs or, sometimes, entire sign combinations with logographic value are known as Sumerograms, a type of heterogram.

The East Semitic languages employed equivalents for many signs that were distorted or abbreviated to represent new values because the syllabic nature of the script as refined by the Sumerians was not intuitive to Semitic speakers.[19] From the beginning of the Middle Bronze Age (20th century BC), the script evolved to accommodate the various dialects of Akkadian: Old Akkadian, Babylonian and Assyrian.[19] At this stage, the former pictograms were reduced to a high level of abstraction, and were composed of only five basic wedge shapes: horizontal, vertical, two diagonals and the Winkelhaken impressed vertically by the tip of the stylus. The signs exemplary of these basic wedges are:

- AŠ (B001, U+12038) 𒀸: horizontal;

- DIŠ (B748, U+12079) 𒁹: vertical;

- GE23, DIŠ tenû (B575, U+12039) 𒀹: downward diagonal;

- GE22 (B647, U+1203A) 𒀺: upward diagonal;

- U (B661, U+1230B) 𒌋: the Winkelhaken.

Except for the Winkelhaken, which has no tail, the length of the wedges' tails could vary as required for sign composition.

Signs tilted by about 45 degrees are called tenû in Akkadian, thus DIŠ is a vertical wedge and DIŠ tenû a diagonal one. If a sign is modified with additional wedges, this is called gunû or "gunification"; if signs are cross-hatched with additional Winkelhaken, they are called šešig; if signs are modified by the removal of a wedge or wedges, they are called nutillu.

"Typical" signs have about five to ten wedges, while complex ligatures can consist of twenty or more (although it is not always clear if a ligature should be considered a single sign or two collated, but distinct signs); the ligature KAxGUR7 consists of 31 strokes.

Most later adaptations of Sumerian cuneiform preserved at least some aspects of the Sumerian script. Written Akkadian included phonetic symbols from the Sumerian syllabary, together with logograms that were read as whole words. Many signs in the script were polyvalent, having both a syllabic and logographic meaning. The complexity of the system bears a resemblance to Old Japanese, written in a Chinese-derived script, where some of these Sinograms were used as logograms and others as phonetic characters.

This "mixed" method of writing continued through the end of the Babylonian and Assyrian empires, although there were periods when "purism" was in fashion and there was a more marked tendency to spell out the words laboriously, in preference to using signs with a phonetic complement.[clarification needed] Yet even in those days, the Babylonian syllabary remained a mixture of logographic and phonemic writing.

Elamite cuneiform

[edit]Elamite cuneiform was a simplified form of the Sumero-Akkadian cuneiform, used to write the Elamite language in the area that corresponds to modern Iran between the 3rd millennium and 4th century BC. Elamite cuneiform at times competed with other local scripts, Proto-Elamite and Linear Elamite. The earliest known Elamite cuneiform text is a treaty between Akkadians and the Elamites that dates back to 2200 BC.[38] Some believe it might have been in use since 2500 BC.[39] The tablets are poorly preserved, so only limited parts can be read, but it is understood that the text is a treaty between the Akkad king Nāramsîn and Elamite ruler Hita, as indicated by frequent references like "Nāramsîn's friend is my friend, Nāramsîn's enemy is my enemy".[38]

The most famous Elamite scriptures and the ones that ultimately led to its decipherment are the ones found in the trilingual Behistun inscriptions, commissioned by the Achaemenid kings.[40] The inscriptions, similar to that of the Rosetta Stone's, were written in three different writing systems. The first was Old Persian, which was deciphered in 1802 by Georg Friedrich Grotefend. The second, Babylonian cuneiform, was deciphered shortly after the Old Persian text. Because Elamite is unlike its neighboring Semitic languages, the script's decipherment was delayed until the 1840s.[38]

Elamite cuneiform appears to have used far fewer signs than its Akkadian prototype and initially relied primarily on syllabograms, but logograms became more common in later texts. Many signs soon acquired highly distinctive local shape variants that are often difficult to recognise as related to their Akkadian prototypes.[41]

Hittite cuneiform

[edit]Hittite cuneiform is an adaptation of Old Assyrian cuneiform to write the Hittite language that emerged c. 1800 BC and was used between the 17th–13th centuries BC. More or less the same Assyrian system was used by the scribes of the Hittite Empire for two other Anatolian languages (a now extinct branch of Indo-European), namely Luwian (alongside the native Anatolian hieroglyphics) and Palaic, as well as for the language isolate Hattic language. When the cuneiform script was adapted to writing Hittite, a layer of Akkadian logographic spellings, also known as Akkadograms, was added to the script, in addition to the Sumerian logograms, or Sumerograms, which were already inherent in the Akkadian writing system and which Hittite also kept. Thus the pronunciations of many Hittite words which were conventionally written by logograms are now unknown.

Hurrian and Urartian cuneiform

[edit]The Hurrian language (attested 2300–1000 BC) and Urartian language (attested in the 9th–6th centuries BC) were also written in adapted versions of Sumero-Akkadian cuneiform. Although the two languages are related, their writing systems seem to have been developed separately. For Hurrian, there were even different systems in different polities (in Mitanni, in Mari, in the Hittite Empire). The Hurrian orthographies were generally characterised by more extensive use of syllabograms and more limited use of logograms than Akkadian. Urartian, in comparison, retained a more significant role for logograms.[41]

Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian cuneiform

[edit](c. 650 BC)

In the Iron Age (c. 10th–6th centuries BC) during the Neo-Assyrian Empire, Assyrian cuneiform was further simplified. The characters remained the same as those of Sumero-Akkadian cuneiforms, but the graphic design of each character relied more heavily on wedges and square angles, making them significantly more abstract:

-

"Assurbanipal King of Assyria"

Aššur-bani-habal šar mat Aššur KI

Same characters, in the classical Sumero-Akkadian script of c. 2000 BC (top), and in the Neo-Assyrian script of the Rassam cylinder, 643 BC (bottom).[42] -

The Rassam cylinder with translation of a segment about the Assyrian conquest of Egypt by Ashurbanipal against "Black Pharaoh" Taharqa, 643 BC

Babylonian cuneiform was simplified along similar lines during that period, albeit to a lesser extent and in a slightly different way. From the 6th century, the Akkadian language was marginalized by Aramaic, written in the Aramaic alphabet, but Akkadian cuneiform remained in use in the literary tradition well into the times of the Parthian Empire in Assyria and Babylonia (250 BC – 226 AD).[43] The last known cuneiform inscription, an astronomical text, was written in 75 AD.[44] The ability to read cuneiform may have persisted until the third century AD.[5]

Derived scripts

[edit]Old Persian cuneiform (5th century BC)

[edit](c. 500 BC)

The complexity of cuneiforms prompted the development of a number of simplified versions of the script. Old Persian cuneiform was developed with an independent and unrelated set of simple cuneiform characters, by Darius the Great in the 5th century BC. Most scholars consider the cuneiform to be independent of other writing systems at the time, such as Elamite, Akkadian, Hurrian, and Hittite cuneiforms.[45]

It formed a semi-alphabetic syllabary, using far fewer wedge strokes than Assyrian used, together with a handful of logograms for frequently occurring words like "god" (𐏎), "king" (𐏋) or "country" (𐏌). This almost purely alphabetical form of the cuneiform script (36 phonetic characters and 8 logograms), was specially designed and used by the early Achaemenid rulers from the 6th century BC down to the 4th century BC.[46]

Because of its simplicity and logical structure, the Old Persian cuneiform script was the first to be deciphered by modern scholars, starting with the accomplishments of Georg Friedrich Grotefend in 1802. Various ancient bilingual or trilingual inscriptions then permitted to decipher the other, much more complicated and more ancient scripts, as far back as to the 3rd millennium Sumerian script.

Ugaritic

[edit]Ugaritic was written using the Ugaritic alphabet, a standard Semitic style alphabet (an abjad) written using the cuneiform method.

Archaeology

[edit]Between 500,000[11] and 2 million cuneiform tablets are estimated to have been excavated in modern times, of which only approximately 30,000[47]–100,000 have been read or published. The British Museum holds the largest collection (approx. 130,000 tablets), followed by the Vorderasiatisches Museum Berlin, the Louvre, the Istanbul Archaeology Museums, the National Museum of Iraq, the Yale Babylonian Collection (approx. 40,000), and Penn Museum. Most of these have "lain in these collections for a century without being translated, studied or published",[11] as there are only a few hundred qualified cuneiformists in the world.[47]

Decipherment

[edit]The decipherment of cuneiform began with the decipherment of Old Persian cuneiform in 1836.

The first cuneiform inscriptions published in modern times were copied from the Achaemenid royal inscriptions in the ruins of Persepolis, with the first complete and accurate copy being published in 1778 by Carsten Niebuhr. Niebuhr's publication was used by Grotefend in 1802 to make the first breakthrough – the realization that Niebuhr had published three different languages side by side and the recognition of the word "king".[48]

The rediscovery and publication of cuneiform took place in the early 17th century, and early conclusions were drawn such as the writing direction and that the Achaemenid royal inscriptions are three different languages, with two different scripts. In 1620, García de Silva Figueroa dated the inscriptions of Persepolis to the Achaemenid period, identified them as Old Persian, and concluded that the ruins were the ancient residence of Persepolis. In 1621, Pietro Della Valle specified the direction of writing from left to right.

In 1762, Jean-Jacques Barthélemy found that an inscription in Persepolis resembled that found on a brick in Babylon. Carsten Niebuhr made the first copies of the inscriptions of Persepolis in 1778 and settled on three different types of writing, which subsequently became known as Niebuhr I, II and III. He was the first to discover the sign for a word division in one of the scriptures. Oluf Gerhard Tychsen was the first to list 24 phonetic or alphabetic values for the characters in 1798.

Actual decipherment did not take place until the beginning of the 19th century, initiated by Georg Friedrich Grotefend in his study of Old Persian cuneiform. He was followed by Antoine-Jean Saint-Martin in 1822 and Rasmus Christian Rask in 1823, who was the first to decipher the name Achaemenides and the consonants m and n. Eugène Burnouf identified the names of various satrapies and the consonants k and z in 1833–1835. Christian Lassen contributed significantly to the grammatical understanding of the Old Persian language and the use of vowels. The decipherers used the short trilingual inscriptions from Persepolis and the inscriptions from Ganjnāme for their work.

-

Niebuhr inscription 1, with the suggested words for "King" (𐎧𐏁𐎠𐎹𐎰𐎡𐎹) highlighted, repeated three times. Inscription now known to mean "Darius the Great King, King of Kings, King of countries, son of Hystaspes, an Achaemenian, who built this Palace".[5] Today known as DPa, from the Palace of Darius in Persepolis, above figures of the king and attendants[49]

-

Niebuhr inscription 2, with the suggested words for "King" (𐎧𐏁𐎠𐎹𐎰𐎡𐎹) highlighted, repeated four times. Inscription now known to mean "Xerxes the Great King, King of Kings, son of Darius the King, an Achaemenian".[5] Today known as XPe, the text of fourteen inscriptions in three languages (Old Persian, Elamite, Babylonian) from the Palace of Xerxes in Persepolis.[50]

In a final step, the decipherment of the trilingual Behistun Inscription was completed by Henry Rawlinson and Edward Hincks. Edward Hincks discovered that Old Persian is partly a syllabary.

In 2023 it was shown that automatic high-quality translation of cuneiform languages like Akkadian can be achieved using natural language processing methods with convolutional neural networks.[51]

Transliteration

[edit]

c. 250 BC

"Antiochus, King, Great King, King of multitudes, King of Babylon, King of countries".

Note that while the images above transcribe the Akkadian pronunciation of the text, the actual spelling is highly logographic and would be strictly transliterated as follows, with the logograms (Sumerograms) capitalised and the syllabograms (phonetic signs) italicised:

1. DIŠan-ti-ʾu-ku-us LUGAL GAL-ú

2. LUGAL dan-nu LUGAL ŠÁR LUGAL E.KI LUGAL KUR-KUR

3. za-ni-in É.SAG.ÍL ù É.ZI.DA[55]

In Unicode:

1. 𒁹𒀭𒋾𒀪𒆪𒊻𒈗𒃲𒌑

2. 𒈗𒆗𒉡𒈗𒎗𒈗𒂊𒆠𒈗𒆳𒆳

3. 𒍝𒉌𒅔𒂍𒊕𒅍𒅇𒂍𒍣𒁕

Cuneiform has a specific format for transliteration. Because of the script's polyvalence, transliteration requires certain choices of the transliterating scholar, who must decide in the case of each sign which of its several possible meanings is intended in the original document. For example, the sign dingir (𒀭) in a Hittite text may represent either the Hittite syllable an or may be part of an Akkadian phrase, representing the syllable il, it may be a Sumerogram, representing the original Sumerian meaning, 'god' or the determinative for a deity. In transliteration, a different rendition of the same glyph is chosen depending on its role in the present context.[56]

Therefore, a text containing DINGIR (𒀭) and A (𒀀) in succession could be construed to represent the Akkadian words "ana", "ila", god + "a" (the accusative case ending), god + water, or a divine name "A" or Water. Someone transcribing the signs would make the decision how the signs should be read and assemble the signs as "ana", "ila", "Ila" ("god"+accusative case), etc. A transliteration of these signs would separate the signs with dashes "il-a", "an-a", "DINGIR-a" or "Da". This is still easier to read than the original cuneiform, but now the reader is able to trace the sounds back to the original signs and determine if the correct decision was made on how to read them. A transliterated document thus presents the reading preferred by the transliterating scholar as well as an opportunity to reconstruct the original text.

There are differing conventions for transliterating different languages written with Sumero-Akkadian cuneiform. The following conventions see wide use across the different fields:

- To disambiguate between homophones, i.e. between signs pronounced identically, the letters that express the pronunciation of a sign are supplemented with subscript numbers. For example, u1 stands for the glyph 𒌋, u2 stands for 𒌑, and u3 stands for 𒅇, all thought to have been pronounced /u/. No. 1 is usually treated as the default interpretation and not indicated explicitly, so u is equivalent to u1. For the numbers 2 and 3, accent diacritics are often used as well: an acute accent stands for no. 2 and a grave accent for no. 3. Thus, u is equivalent to u1 (𒌋), ú is equivalent to u2 (𒌑) and ù to u3 (𒅇). The sequence of numbering is conventional but essentially arbitrary and a consequence of the history of decipherment.

- As shown above, signs as such are represented in capital letters. The specific reading selected in the transliteration is represented in small letters. Thus, capital letters can be used to indicate a so-called Diri compound, in which a sequence of signs does not stand for a combination of their usual readings, as in the spelling 𒅆𒀀 IGI.A for the word imhur 'foam' [[#Early Dynastic cuneiform (c. 2500 BC)|given above]]. Capital letters may also be used to indicate a Sumerogram, for example, KÙ.BABBAR 𒆬𒌓 – Sumerian for "silver" – being used with the intended Akkadian reading kaspum, "silver", or simply a sign sequence of whose reading the editor is uncertain. Naturally, the "real" reading, if it is clear, will be presented in small letters in the transliteration: IGI.A will be rendered as imhur4. An Akkadogram in Hittite is indicated by capital letters as well, but they are italicised: e.g. ME-E transcribes the sign sequence 𒈨𒂊 when the intended reading is Hittite wātar "water", based on Akkadian mê "water (accusative-genitive case)".

- Another convention is that determinatives are written in superscript: thus, the sequence 𒀕𒆠 (the name of the city Uruk) is transliterated as unugki to show that the second sign, KI, meaning "earth", isn't intended to be pronounced, but only specifies the type of meaning the former sign has. In this case, that it is a place name. A few common determinatives are transliterated with abbreviations: for example, d represents the sign 𒀭 DINGIR when it serves as an indicator that one or more following signs form the name of a deity, as seen in the transliteration of 𒀭𒂗𒆤 as den-líl "Enlil". 𒁹 DIŠ 'one' and 𒊩 MUNUS 'woman' as prefixed determinatives for male and female personal names, uncommon in Sumerian, but subsequently used for some other languages, are often rendered with the abbreviations m and f for "masculine" and "feminine".

- In Sumerian transliteration, a multiplication sign ('×') is used to indicate typographic ligatures. For example, the sign 𒅻 NUNDUM, which stands for the word nundum "lip", can also be designated as KA×NUN, which indicates that it is a compound of the signs 𒅗 KA "mouth" and 𒉣 NUN "prince".

Since the Sumerian language has only been widely known and studied by scholars for approximately a century, changes in the accepted reading of Sumerian names have occurred from time to time. Thus the name of a king of Ur, 𒌨𒀭𒇉, read Ur-Bau at one time,[citation needed] was later read as Ur-Engur, and is now read as Ur-Nammu or Ur-Namma; for Lugal-zage-si (𒈗𒍠𒄀𒋛), a king of Uruk, some scholars continued to read Ungal-zaggisi; and so forth. With some names of the older period, there was often uncertainty whether their bearers were Sumerians or Semites. If the former, then their names could be assumed to be read as Sumerian. If they were Semites, the signs for writing their names were probably to be read according to their Semitic equivalents. Though occasionally, Semites might be encountered bearing genuine Sumerian names.

There was doubt whether the signs composing a Semite's name represented a phonetic reading or a logographic compound. Thus, e.g. when inscriptions of a Semitic ruler of Kish, whose name was written 𒌷𒈬𒍑, Uru-mu-ush, were first deciphered, that name was first taken to be logographic because uru mu-ush could be read as "he founded a city" in Sumerian, and scholars accordingly retranslated it back to the original Semitic as Alu-usharshid. It was later recognized that the URU sign (𒌷) can also be read as rí and that the name is that of the Akkadian king Rimush.

Sign inventories

[edit]

The Sumerian cuneiform script had on the order of 1,000 distinct signs, or about 1,500 if variants are included. This number was reduced to about 600 by the 24th century BC and the beginning of Akkadian records. Not all Sumerian signs are used in Akkadian texts, and not all Akkadian signs are used in Hittite.

A. Falkenstein (1936) lists 939 signs used in the earliest period, late Uruk, 34th to 31st centuries. (See #Bibliography for the works mentioned in this paragraph.) With an emphasis on Sumerian forms, Deimel (1922) lists 870 signs used in the Early Dynastic II period (28th century, Liste der archaischen Keilschriftzeichen or "LAK") and for the Early Dynastic IIIa period (26th century, Šumerisches Lexikon or "ŠL").

Rosengarten (1967) lists 468 signs used in Sumerian (pre-Sargonian) Lagash. Mittermayer and Attinger (2006, Altbabylonische Zeichenliste der Sumerisch-Literarischen Texte or "aBZL") list 480 Sumerian forms, written in Isin-Larsa and Old Babylonian times. Regarding Akkadian forms, the standard handbook for many years was Borger (1981, Assyrisch-Babylonische Zeichenliste or "ABZ") with 598 signs used in Assyrian and Babylonian writing, recently superseded by Borger (2004, Mesopotamisches Zeichenlexikon or "MesZL") with an expansion to 907 signs, an extension of their Sumerian readings and a new numbering scheme. The introduction of a cursive script in the Old Babylonian period coincided with the expansion of literacy beyond institutional settings, leading to greater variation in writing styles. This shift may have influenced the increasing number of documented signs, as reflected in later sign lists. As writing adapted to new contexts—whether for administrative, literary, or private use—the need for expanded and specialized sign inventories became more apparent.[57]

Signs used in Hittite cuneiform are listed by Forrer (1922), Friedrich (1960) and Rüster and Neu (1989, Hethitisches Zeichenlexikon or "HZL"). The HZL lists a total of 375 signs, many with variants (for example, 12 variants are given for number 123 EGIR).

Syllabary

[edit]The tables below contain the transliteration schemes of Sumero-Akkadian syllabograms.

| Va | Ve | Vi | Vu | aV | eV | iV | uV | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a = 𒀀 á (a₂) = 𒀉 |

e = 𒂊 é (e₂) = 𒂍 |

i = 𒄿 í (i₂) = 𒐊 |

u = 𒌋 ú (u₂) = 𒌑 |

a = 𒀀 á (a₂) = 𒀉 |

e = 𒂊 é (e₂) = 𒂍 |

i = 𒄿 í (i₂) = 𒐊 |

u = 𒌋 ú (u₂) = 𒌑 |

|||

| a- | ai = 𒀀𒀀 | ea = 𒀀 | ia = 𒅀 iá (ia₂) = 𒐊 |

ua = 𒇇 |

-a | |||||

| e- | ea = 𒀀 | ie = 𒅀 | -e | |||||||

| i- | ia = 𒅀 iá (ia₂) = 𒐊 |

ie = 𒅀 | ii = 𒅀 iì (ii₃) = 𒂊 |

iu = 𒅀 iú (iu₂) = 𒉿 |

ai = 𒀀𒀀 | ii = 𒅀 iì (ii₃) = 𒂊 |

-i | |||

| u- | ua = 𒇇 |

iu = 𒅀 iú (iu₂) = 𒉿 |

-u |

| Ca | Ce | Ci | Cu | aC | eC | iC | uC | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ʾ- | ʾa = 𒀪 |

ʾe = 𒀪 ʾé (ʾe₂) = 𒄴 |

ʾi = 𒀪 |

ʾu = 𒀪 |

aʾ = 𒀪 |

eʾ = 𒀪 |

iʾ = 𒀪 íʾ (iʾ₂) = 𒄴 |

uʾ = 𒀪 |

-ʾ | |

| b- | ba = 𒁀 bá (ba₂) = 𒉺 |

be = 𒁁 |

bi = 𒁉 bí (bi₂) = 𒉈 |

bu = 𒁍 bú (bu₂) = 𒆜 |

ab = 𒀊 |

eb = 𒅁 éb (eb₂) = 𒌈 |

ib = 𒅁 íb (ib₂) = 𒌈 |

ub = 𒌒 |

-b | |

| d- | da = 𒁕 dá (da₂) = 𒋫 |

de = 𒁲 dé (de₂) = 𒌣 |

di = 𒁲 dí (di₂) = 𒊹 |

du = 𒁺 dú (du₂) = 𒌅 |

ad = 𒀜 |

ed = 𒀉 |

id = 𒀉 íd (id₂) = 𒀀𒇉 |

ud = 𒌓 |

-d | |

| g- | ga = 𒂵 gá (ga₂) = 𒂷 |

ge = 𒄀 gé (ge₂) = 𒆤 |

gi = 𒄀 gí (gi₂) = 𒆤 |

gu = 𒄖 gú (gu₂) = 𒄘 |

ag = 𒀝 |

eg = 𒅅 |

ig = 𒅅 |

ug = 𒊌 úg (ug₂) = 𒄊, 𒊊 |

-g | |

| ḫ- | ḫa = 𒄩 |

ḫe = 𒄭 ḫé (ḫe₂) = 𒃶 |

ḫi = 𒄭 ḫí (ḫi₂) = 𒃶 |

ḫu = 𒄷 |

aḫ = 𒄴 |

eḫ = 𒄴 |

iḫ = 𒄴 íḫ (iḫ₂) = 𒀪 |

uḫ = 𒄴 |

-ḫ | |

| k- | ka = 𒅗 ká (ka₂) = 𒆍 |

ke = 𒆠 |

ki = 𒆠 |

ku = 𒆪 kú (ku₂) = 𒅥 |

ak = 𒀝 àk (ak₃) = 𒋃 |

ek = 𒅅 | ik = 𒅅 | uk = 𒊌 | -k | |

| l- | la = 𒆷 lá (la₂) = 𒇲 |

le = 𒇷 |

li = 𒇷 lí (li₂) = 𒉌 |

lu = 𒇻 lú (lu₂) = 𒇽 |

al = 𒀠 |

el = 𒂖 |

il = 𒅋 íl (il₂) = 𒅍 |

ul = 𒌌 úl (ul₂) = 𒉡 |

-l | |

| m- | ma = 𒈠 má (ma₂) = 𒈣 |

me = 𒈨 mé (me₂) = 𒈪 |

mi = 𒈪 |

mu = 𒈬 mú (mu₂) = 𒊬 |

am = 𒄠 |

em = 𒅎 |

im = 𒅎 |

um = 𒌝 úm (um₂) = 𒌓 |

-m | |

| n- | na = 𒈾 ná (na₂) = 𒈿 |

ne = 𒉈 né (ne₂) = 𒉌 |

ni = 𒉌 ní (ni₂) = 𒅎 |

nu = 𒉡 nú (nu₂) = 𒈿 |

an = 𒀭 án (an₂) = 𒄒 |

en = 𒂗 én (en₂) = 𒋙𒀭, 𒌋𒀭 |

in = 𒅔 |

un = 𒌦 |

-n | |

| p- | pa = 𒉺 pá (pa₂) = 𒁀 |

pe = 𒉿 |

pi = 𒉿 pí (pi₂) = 𒁉 |

pu = 𒁍 |

ap = 𒀊 |

ep = 𒅁 ép (ep₂) = 𒌈 |

ip = 𒅁 íp (ip₂) = 𒌈 |

up = 𒌒 úp (up₂) = 𒂠 |

-p | |

| q- | qa = 𒋡 |

qe = 𒆥 |

qi = 𒆥 |

qu = 𒄣 |

aq = 𒀝 | eq = 𒅅 | iq = 𒅅 | uq = 𒊌 uq₅ = 𒂦 |

-q | |

| r- | ra = 𒊏 |

re = 𒊑 |

ri = 𒊑 rí (ri₂) = 𒌷 |

ru = 𒊒 rú (ru₂) = 𒆕 |

ar = 𒅈 |

er = 𒅕 ér (er₂) = 𒀀𒅆 |

ir = 𒅕 ír (ir₂) = 𒀀𒅆 |

ur = 𒌨 úr (ur₂) = 𒌫 |

-r | |

| s- | sa = 𒊓 sá (sa₂) = 𒁲 |

se = 𒋛 sé (se₂) = 𒍣 |

si = 𒋛 sí (si₂) = 𒍣 |

su = 𒋢 sú (su₂) = 𒍪 |

as = 𒊍 |

es = 𒄑 |

is = 𒄑 |

us = 𒊻 |

-s | |

| ṣ- | ṣa = 𒍝 ṣà (ṣa₃) = 𒀭 |

ṣe = 𒍢 ṣé (ṣe₂) = 𒍣 |

ṣi = 𒍢 |

ṣu = 𒍮 ṣú (ṣu₂) = 𒍪 |

aṣ = 𒊍 |

eṣ = 𒄑 èṣ (eṣ₃) = 𒀊 |

iṣ = 𒄑 |

uṣ = 𒊻 |

-ṣ | |

| ś- | śa = 𒊓 śá (śa₂) = 𒁲 |

śe = 𒋛 śé (śe₂) = 𒋝 |

śi = 𒋛 |

śu = 𒋢 |

aś = 𒀾 | iś = 𒅖 iś₇ = 𒀊 |

uś = 𒍑 |

-ś | ||

| š- | ša = 𒊭 šá (ša₂) = 𒃻 |

še = 𒊺 šé (še₂) = 𒋛 |

ši = 𒅆 |

šu = 𒋗 šú (šu₂) = 𒋙 |

aš = 𒀸 áš (aš₂) = 𒀾 |

eš = 𒌍 éš (eš₂) = 𒂠 |

iš = 𒅖 íš (iš₂) = 𒆜 |

uš = 𒍑 úš (uš₂) = 𒁁 |

-š | |

| t- | ta = 𒋫 tá (ta₂) = 𒁕 |

te = 𒋼 té (te₂) = 𒊹 |

ti = 𒋾 tí (ti₂) = 𒊹 |

tu = 𒌅 tú (tu₂) = 𒌓 |

at = 𒀜 |

et = 𒀉 | it = 𒀉 |

ut = 𒌓 |

-t | |

| ṭ- | ṭa = 𒁕 |

ṭe = 𒁲 |

ṭi = 𒁲 |

ṭu = 𒂅 |

aṭ = 𒀜 áṭ (aṭ₂) = 𒄉 |

eṭ = 𒀉 | iṭ = 𒀉 | uṭ = 𒌓 | -ṭ | |

| w- | wa = 𒉿 |

we = 𒉿 wé (we₂) = 𒊄 |

wi = 𒉿 |

wu = 𒉿 |

aw = 𒉿 | ew = 𒉿 | iw = 𒉿 | uw = 𒉿 | -w | |

| y- (j-) | ya / ja = 𒉿 | ye / je = 𒉿 | yi / ji = 𒉿 |

yu / ju = 𒉿 | ay / aj = 𒀀𒀀 | -y (-j) | ||||

| z- | za = 𒍝 |

ze = 𒍣 |

zi = 𒍣 |

zu = 𒍪 zú (zu₂) = 𒅗 |

az = 𒊍 |

ez = 𒄑 |

iz = 𒄑 |

uz = 𒊻 |

-z |

| aCV | eCV | iCV | uCV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| -ʾ- | àʾa = 𒆹 | uʾa = 𒇇𒀀 | ||

| eʾi = 𒂍𒀀 | uʾi = 𒇇𒀀 | |||

| eʾu = 𒂍𒀀 | uʾu = 𒇇𒀀 | |||

| -b- | aba = 𒀊 |

úba (uba₂) = 𒂠 | ||

| ubi = 𒃴 úbi (ubi₂) = 𒋦 | ||||

| ubu = 𒀹 úbu (ubu₂) = 𒌒 | ||||

| -d- | edi = 𒃄 | idi = 𒃟 | ||

| udu = 𒇻 údu (udu₂) = 𒋗𒁁 | ||||

| -g- | aga = 𒂆 |

ega = 𒀀𒈪𒀀 éga (ega₂) = 𒉧 |

iga = 𒅅 | uga = 𒌑𒉀𒂵 úga (uga₂) = 𒀀𒅗 |

| ege = 𒂠 ége (ege₂) = 𒊩𒂠 |

||||

| egi = 𒂠 égi (egi₂) = 𒊩𒂠 |

igi = 𒅆 |

|||

| agu = 𒂆 | egu = 𒀀𒆪 | igu = 𒅆 | ugu = 𒌋𒅗 | |

| -ḫ- | aḫa = 𒄴 |

|||

| eḫe = 𒀉𒌓𒁺 | ||||

| aḫi = 𒋀 áḫi (aḫi₂) = 𒀉 |

eḫi = 𒀉𒌓𒁺 | |||

| uḫu = 𒄴 úḫu (uḫu₂) = 𒌔 | ||||

| -i- | aia = 𒀀𒀀 |

uia = 𒌋𒐊 | ||

| -k- | aka = 𒀝 |

|||

| eki = 𒂊 | ||||

| iku = 𒃷 | uku = 𒂆 |

|||

| -l- | ala = 𒌷 |

ela = 𒀀𒆗 | ila = 𒀭 íla (ila₂) = 𒅍 |

ula = 𒌌 úla (ula₂) = 𒃪 |

| ale = 𒌷 | ele = 𒌋𒅗 éle (ele₂) = 𒂖 |

|||

| ali = 𒌷 | ili = 𒀭 |

uli = 𒅴 | ||

| alu / ālu = 𒌷 | ilu = 𒀭 |

ulu = 𒌌 | ||

| -m- | ama = 𒂼 |

uma = 𒍻 | ||

| ame = 𒂼 áme (ame₂) = 𒃣 |

eme = 𒅴 éme (eme₂) = 𒎘 |

|||

| imi = 𒅎 ími (imi₂) = 𒂼 |

||||

| umu = 𒌝 | ||||

| -n- | ana = 𒁹 |

ina = 𒀸 ína (ina₂) = 𒅆 |

||

| eni = 𒂗 | ini = 𒅔 |

|||

| anu = 𒀭 | enu = 𒂗 ēnu = 𒅆 |

īnu = 𒅆, 𒅆 |

unu = 𒀔 únu (unu₂) = 𒋼𒀕 | |

| -q- | aqa = 𒀝 | |||

| -r- | ara = 𒊭 ára (ara₂) = 𒌒 |

era = 𒀴𒊏 |

íra = 𒀀𒅆 | ura₁₅ = 𒋀𒀕 ura₁₆ = 𒋀𒀊 |

| ari = 𒌵 |

eri = 𒌷 eri₄ = 𒌷 ? |

iri = 𒌷 |

uri = 𒌵 | |

| aru = 𒉺 | eru = 𒀴 |

uru = 𒌷 úru (uru₂) = 𒍍 | ||

| -s- | asa = 𒊍 | usa = 𒐍, 𒑄 | ||

| asi = 𒀀𒌁 | esi = 𒆗 | isi = 𒅖 | usi = 𒃥 | |

| usu = 𒀉𒆗 úsu (usu₂) = 𒍑 | ||||

| -š- | aša = 𒀸 |

eša = 𒀀𒌁 éša (eša₂) = 𒌍 |

||

| eše = 𒌍 | ||||

| iši = 𒅖 íši (iši₂) = 𒋙𒀯 | ||||

| ušu = 𒁔 | ||||

| -t- | ita₄ = 𒀭𒀀𒇉 ita₅ = 𒀀𒇉 |

uta = 𒌓 | ||

| iti = 𒌗 íti (iti₂) = 𒌛 |

||||

| itu = 𒌗 |

utu = 𒌓 | |||

| -y- (-i̭- / -j-) | aya / ai̭a / aja = 𒀀𒀀 |

iya / ija = 𒀀𒀀 |

||

| aye / ai̭e / aje = 𒀀𒀀 | iye / ije = 𒀀𒀀 | |||

| ayi / ai̭i / aji = 𒀀𒀀 | iyi / iji = 𒀀𒀀 | |||

| ayu / ai̭u / aju = 𒀀𒀀 | iyu / iju = 𒀀𒀀 | |||

| -z- | aza = 𒊍 | ùza (uza₃) = 𒍚 | ||

| izi = 𒉈 ízi (izi₂) = 𒆠𒉈 |

||||

| azu = 𒉙 | izu = 𒉈 | uzu = 𒍜 |

| CaV/CaC | CeV/CeC | CiV/CiC | CuV/CuC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b- | baʾ = 𒁁 | |||

| bab = 𒉽 báb (bab₂) = 𒌓 | ||||

| bad = 𒁁 |

bid = 𒂍 | |||

| bag = 𒄷 | big = 𒋝 | bug = 𒈮 | ||

| baḫ = 𒄷 bàḫ (baḫ₃) = 𒈜 |

buḫ = 𒈜 | |||

| bak = 𒄷 | bik = 𒋝 | buk = 𒈮 | ||

| bal = 𒁄 |

bel = 𒉈 bél (bel₂) = 𒉋 |

bil = 𒉈 |

bul = 𒇧 | |

| bum = 𒅤 | ||||

| ban = 𒉼 |

bin = 𒀳 | bun = 𒇌 bún (bun₂) = 𒅮 | ||

| bap = 𒉽 | ||||

| baq = 𒄷 | biq = 𒋝 | |||

| bar = 𒁇 bár (bar₂) = 𒁈 |

ber = 𒄵 |

bir = 𒄵 bír (bir₂) = 𒌓 |

bur = 𒁓 búr (bur₂) = 𒁔 | |

| bís (bis₂) = 𒄫 | ||||

| baš = 𒈦 | beš₁₂ = 𒌓 | biš = 𒄫 | buš = 𒆜 búš (buš₂) = 𒄫 | |

| bat = 𒁁 |

bet = 𒂍 | bit = 𒂍 bít (bit₂) = 𒁁 |

||

| baṭ = 𒁁 | biṭ = 𒂍 | |||

| biz = 𒁉 | ||||

| d- | ||||

| dab = 𒁳 |

dib = 𒁳 díb (dib₂) = 𒆪 |

dub = 𒁾 | ||

| dad = 𒋺 | did = 𒅎 | dud = 𒉺𒍜 | ||

| dag = 𒁖 |

dig = 𒉌 | dug = 𒂁 | ||

| daḫ = 𒈭 | deḫ = 𒁾 |

diḫ = 𒁾 |

duḫ = 𒂃 | |

| dak = 𒁖 dàk (dak₃) = 𒉌𒂟 |

dik = 𒉌 | duk = 𒂁 dúk (duk₂) = 𒌇 | ||

| dal = 𒊑 |

del = 𒀸 dél (del₂) = 𒇺 |

dil = 𒀸 | dul = 𒌋𒌆 dúl (dul₂) = 𒇥 | |

| dam = 𒁮 |

dém = 𒁶 | dim = 𒁴 |

dum = 𒌈 | |

| dan = 𒆗 dán (dan₂) = 𒃞 |

den = 𒁷 | din = 𒁷 |

dun = 𒂄 | |

| dap = 𒁳 dáp (dap₂) = 𒋰 |

dip = 𒁳 | dup = 𒁾 dúp (dup₂) = 𒂀 | ||

| daq = 𒁖 |

diq = 𒉌 | duq = 𒂁 | ||

| dar = 𒁯 |

der = 𒋛𒀀 | dir = 𒋛𒀀 |

dur = 𒄙 dúr (dur₂) = 𒂉, 𒆪 | |

| das = 𒌨 | ||||

| daš = 𒌨 |

deš = 𒁹 |

diš = 𒁹 |

duš = 𒆪 dúš (duš₂) = 𒁹 | |

| dat = 𒋺 | ||||

| g- | gab = 𒃮 |

gib = 𒄃 |

gub = 𒁺 | |

| gad = 𒃰 | gid = 𒆤 |

gud = 𒄞 gúd (gud₂) = 𒊥 | ||

| gag = 𒆕 | gig = 𒈪𒉭 |

gug = 𒍝𒄢 | ||

| gak = 𒆕 | gik = 𒈪𒉭 | gúk (guk₂) = 𒈖 | ||

| gal = 𒃲 gál (gal₂) = 𒅅 |

gel = 𒄃 gél (gel₂) = 𒆸 |

gil = 𒄃 |

gul = 𒄢 | |

| gam = 𒃵 |

gem = 𒁶 gèm (gem₃) = 𒊩𒆳 |

gim = 𒁶 gím (gim₂) = 𒂅 |

gum = 𒄣 | |

| gan = 𒃶 |

gen = 𒁺 |

gin = 𒁺 gín (gin₂) = 𒂅 |

gun = 𒄘𒌦 | |

| gap = 𒃮 gáp (gap₂) = 𒆏 |

gíp (gip₂) = 𒄒 | gup = 𒁺 gúp (gup₂) = 𒇷 | ||

| giq = 𒈪𒉭 | guq = 𒍝𒄢 | |||

| gar = 𒃻 gár (gar₂) = 𒂶 |

ger = 𒄫 |

gir = 𒄫 gír (gir₂) = 𒄈 |

gur = 𒄥 gúr (gur₂) = 𒑲 | |

| gas = 𒄤 gás (gas₂) = 𒄣 |

gis = 𒄑 | |||

| gaṣ = 𒄤 | giṣ = 𒄑 | |||

| gaš = 𒁉 | geš = 𒄑 |

giš = 𒄑 |

guš = 𒋢 | |

| gat = 𒃰 |

git = 𒆤 gít (git₂) = 𒁍 |

|||

| gíṭ (giṭ₂) = 𒁍 | ||||

| gaz = 𒄤 gáz (gaz₂) = 𒄣 |

gez = 𒄑 | giz = 𒄑 | guz = 𒈝 | |

| ḫ- | ḫab = 𒆸 ḫáb (ḫab₂) = 𒇥 |

ḫub = 𒄽 ḫúb (ḫub₂) = 𒄸 | ||

| ḫad = 𒉺 |

ḫud = 𒉺 | |||

| ḫug = 𒂠 | ||||

| ḫal = 𒄬 ḫál (ḫal₂) = 𒍮 |

ḫul = 𒅆𒌨 | |||

| ḫum = 𒈝 | ||||

| ḫun = 𒂠 | ||||

| ḫap = 𒆸 | ḫup = 𒄽 ḫúp (ḫup₂) = 𒄸 | |||

| ḫar = 𒄯 |

ḫer = 𒂡 | ḫir = 𒂡 ḫír (ḫir₂) = 𒄯 |

ḫur = 𒄯 | |

| ḫas = 𒋻 |

ḫus = 𒈝 ḫús (ḫus₂) = 𒋻 | |||

| ḫaṣ = 𒋻 ḫáṣ (ḫaṣ₂) = 𒉺 |

||||

| ḫaš = 𒋻 |

ḫeš = 𒌓 |

ḫiš = 𒌓 |

ḫuš = 𒄭𒄊 ḫúš (ḫuš₂) = 𒄊 | |

| ḫat = 𒉺 | ||||

| ḫaṭ = 𒉺 | ||||

| ḫaz = 𒋻 ḫáz (ḫaz₂) = 𒉺 |

ḫuz = 𒈝 | |||

| k- | kua = 𒄩 kua (kuá₂) = 𒌔 | |||

| kab = 𒆏 káb (kab₂) = 𒅘 |

kib = 𒄒 | kub = 𒁺 | ||

| kad = 𒃰 kád (kad₂) = 𒆐 |

kid = 𒆤 kíd (kid₂) = 𒋺 |

kud = 𒋻 | ||

| kag = 𒆕 kág (kag₂) = 𒅗 |

kíg (kig₂) = 𒆥 | kug = 𒆬 | ||

| kak = 𒆕 | kik = 𒈪𒉭 | kuk = 𒆬 kúk (kuk₂) = 𒈖 | ||

| kal = 𒆗 |

kel = 𒆸 kèl (kel₃) = 𒇔 |

kil = 𒆸 |

kul = 𒆰 kúl (kul₂) = 𒄢 | |

| kam = 𒄰 |

kem = 𒁶 | kim = 𒁶 |

kum = 𒄣 | |

| kan = 𒃶 |

kèn (ken₃) = 𒆳 | kin = 𒆥 kín (kin₂) = 𒄯 |

kun = 𒆲 kún (kun₂) = 𒉺 | |

| kap = 𒆏 kàp (kap₃) = 𒃮 |

kep = 𒄒 | kip = 𒄒 | kup = 𒁺 | |

| kaq = 𒆕 | ||||

| kar = 𒋼𒀀 |

ker = 𒄫 |

kir = 𒄫 kír (kir₂) = 𒀚 |

kur = 𒆳 kúr (kur₂) = 𒉽 | |

| kas = 𒆜 kás (kas₂) = 𒁉 |

kis = 𒆧 kís (kis₂) = 𒄑 |

kus = 𒋢 kús (kus₂) = 𒈝 | ||

| kaṣ = 𒆜 |

kiṣ = 𒆧 | kúṣ (kuṣ₂) = 𒈝 | ||

| kaš = 𒁉 |

keš = 𒆧 kéš (keš₂) = 𒂡 |

kiš = 𒆧 kíš (kiš₂) = 𒂡 |

kuš = 𒋢 kúš (kuš₂) = 𒊨 | |

| kat = 𒃰 |

ket = 𒆤 | kit = 𒆤 |

kut = 𒋻 kút (kut₂) = 𒃰 | |

| kiṭ = 𒆤 | ||||

| kaz₈ = 𒄮 kaz₉ = 𒌓𒄯 |

kuz = 𒋢 kùz (kuz₃) = 𒆪 | |||

| l- | lab = 𒆗 láb (lab₂) = 𒈜 |

leb = 𒈜 | lib = 𒈜 |

lub = 𒈜 |

| lad = 𒆳 | lid = 𒀖 líd (lid₂) = 𒉌 |

lud = 𒂁 | ||

| lag = 𒋃 | lig = 𒌨 | lug = 𒇻 lúg (lug₂) = 𒉺 | ||

| laḫ = 𒌓 láḫ (laḫ₂) = 𒂟 |

liḫ = 𒌓 |

luḫ = 𒈛 | ||

| lak = 𒋃 | lik = 𒌨 lík (lik₂) = 𒋃 |

|||

| lal = 𒇲 |

lél (lel₂) = 𒆤 lel₄ = 𒆦 |

lil = 𒇸 líl (lil₂) = 𒆤 |

lul = 𒈜 | |

| lam = 𒇴 lám (lam₂) = 𒉈 |

lem = 𒅆 lem₄ = 𒉈 |

lim = 𒅆 |

lum = 𒈝 | |

| lan = 𒉺 | ||||

| lap = 𒆗 | lép (₂) = 𒆗 | lip = 𒈜 |

lup = 𒈜 | |

| laq = 𒋃 | leq = 𒌨 | liq = 𒌨 |

||

| lar = 𒉺 | lir = 𒉪 | |||

| lis = 𒇺 | ||||

| liš = 𒇺 | ||||

| lat = 𒆳 | lit = 𒀖 | lut = 𒂁 | ||

| liṭ = 𒀖 líṭ (liṭ₂) = 𒂁 |

||||

| liz = 𒇺 | ||||

| m- | mua = 𒉺 | |||

| maʾ = 𒈣 | ||||

| mad = 𒆳 | mid = 𒁁 | mud = 𒄷𒄭 múd (mud₂) = 𒁁 | ||

| mug = 𒈮 múg (mug₂) = 𒊩𒆷 | ||||

| maḫ = 𒈤 |

meḫ = 𒈤 | miḫ = 𒈤 | muḫ = 𒌋𒅗 | |

| muk = 𒈮 | ||||

| mal = 𒂷 |

mel = 𒅖 mèl (mel₃) = 𒆠𒉈 |

mil = 𒅖 | mul = 𒀯 | |

| mam = 𒌋𒌋 |

mim = 𒈫 |

mum = 𒌣 | ||

| man = 𒌋𒌋 màn (man₃) = 𒐀 |

men = 𒃞 |

min = 𒈫 mín (min₂) = 𒊩 |

mun = 𒁵 | |

| muq = 𒈮 | ||||

| mar = 𒈥 |

mer = 𒂆 |

mir = 𒂆 |

mur = 𒄯 múr (mur₂) = 𒌘 | |

| mas = 𒈦 | mes = 𒈩 |

mis = 𒈩 | mus = 𒈲 | |

| maṣ = 𒈦 | meṣ = 𒈩 | miṣ = 𒈩 | ||

| maś = 𒈦 | ||||

| maš = 𒈦 |

meš = 𒈨𒌍 |

miš = 𒈩 |

muš = 𒈲 múš (muš₂) = 𒈽 | |

| mat = 𒆳 |

met = 𒁁 | mit = 𒁁 | mut = 𒄷𒄭 mút (mut₂) = 𒁁 | |

| maṭ = 𒆳 | meṭ = 𒁁 | miṭ = 𒁁 | muṭ = 𒄷𒄭 | |

| n- | nab = 𒀮 |

nib = 𒊋 níb (nib₂) = 𒀮 |

||

| nad = 𒆳 nàd (nad₃) = 𒈿 |

nid = 𒍑 | nud = 𒈿 | ||

| nag = 𒅘 nág (nag₂) = 𒉀 |

nig = 𒊩𒌨 |

nug = 𒋐 núg (nug₂) = 𒋊 | ||

| náḫ (naḫ₂) = 𒂠 | ||||

| nak = 𒅘 |

nék (nek₂) = 𒃻 | nik = 𒊩𒌨 | ||

| nam = 𒉆 |

nem = 𒉏 ném (nem₂) = 𒊩𒌆 |

nim = 𒉏 |

num = 𒉏 núm (num₂) = 𒈝 | |

| nan = 𒋀 |

nen = 𒊩𒌆 nen₉ = 𒊩𒆪 |

nin = 𒊩𒌆 nín (nin₂) = 𒈹 |

nun = 𒉣 | |

| nap = 𒀮 náp (nap₂) = 𒀯 |

níp (nip₂) = 𒀮 | |||

| naq = 𒅘 | niq = 𒊩𒌨 níq (niq₂) = 𒃻 | |||

| nar = 𒈜 nàr (nar₃) = 𒉪 |

ner = 𒉪 | nir = 𒉪 nír (nir₂) = 𒍝𒂅 |

nur = 𒉪 | |

| nes = 𒌋𒌋 | nis = 𒌋𒌋 nís (nis₂) = 𒄑 |

nus = 𒉭 | ||

| naš = 𒌋𒌋 | neš = 𒌋𒌋 néš (neš₂) = 𒄑 |

niš = 𒌋𒌋 níš (niš₂) = 𒄑 |

||

| nat = 𒆳 nát (nat₂) = 𒄿 |

nit = 𒍑 | |||

| neṭ = 𒍑 | niṭ = 𒍑 | |||

| nuz = 𒉭 | ||||

| p- | pab = 𒉽 | |||

| pad = 𒉻 |

pid = 𒂍 píd (pid₂) = 𒁁 | |||

| pag = 𒄷 | pig = 𒋝 | pug = 𒈮 | ||

| paḫ = 𒈜 pàḫ (paḫ₃) = 𒄷 |

piḫ = 𒈜 | puḫ = 𒈜 | ||

| pak = 𒄷 | pik = 𒋝 | puk = 𒈮 | ||

| pal = 𒁄 | pel = 𒉈 |

pil = 𒉈 píl (pil₂) = 𒉋 |

pul = 𒇧 | |

| pum = 𒅤 | ||||

| pan = 𒉼 |

pin = 𒀳 | |||

| pap = 𒄷 | ||||

| paq = 𒄷 | piq = 𒋝 | púq (puq₂) = 𒄷 | ||

| par = 𒌓 pár (par₂) = 𒁇 |

per = 𒌓 |

pir = 𒌓 |

pur = 𒁓 pur₁₃ = 𒉽𒉽 | |

| pis = 𒄫 | pus = 𒄫 | |||

| paš = 𒄫 | peš = 𒄫 péš (peš₂) = 𒋝𒋙𒁷, 𒉾 |

piš = 𒄫 |

púš (puš₂) = 𒉽𒄬 | |

| pat = 𒉻 pát (pat₂) = 𒁁 |

pet = 𒂍 pét (pet₂) = 𒁁 |

pit = 𒂍 pít (pit₂) = 𒁁 |

||

| paṭ = 𒉻 páṭ (pat₂) = 𒁁 |

piṭ = 𒂍 | |||

| q- | qab = 𒃮 |

qeb = 𒄒 | qib = 𒄒 | qub = 𒁺 |

| qad = 𒋗 |

qid = 𒆤 |

qud = 𒋻 | ||

| qal = 𒃲 |

qel = 𒆸 | qil = 𒆸 qíl (qil₂) = 𒄃 |

qul = 𒆰 qúl (qul₂) = 𒄢 | |

| qam = 𒑲 qám (qam₂) = 𒄰 |

qim = 𒁶 | qum = 𒄣 | ||

| qan = 𒃶 qán (qan₂) = 𒄀 |

qin = 𒆥 | qun = 𒆲 | ||

| qap = 𒃮 qáp (qap₂) = 𒆏 |

qip = 𒄒 | qup = 𒁺 qúp (qup₂) = 𒄽 | ||

| qaq = 𒆕 | qiq = 𒈪𒉭 | |||

| qar = 𒃼 |

qer = 𒄫 |

qir = 𒄫 qír (qir₂) = 𒉐 |

qur = 𒄥 | |

| qis = 𒆧 | ||||

| qiš = 𒆧 | ||||

| qat = 𒋗 qát (qat₂) = 𒋗𒈫 |

qet = 𒆤 | qit = 𒆤 |

qut = 𒋻 | |

| r- | rab = 𒊐 |

reb = 𒆗 | rib = 𒆗 | rub = 𒆗 |

| rad = 𒋥 rád (rad₂) = 𒅐 |

red = 𒈩 | rid = 𒈩 | rud = 𒋥 | |

| rag = 𒊩 | rig = 𒋆 ríg (rig₂) = 𒍮 |

rug = 𒊿 rúg (rug₂) = 𒉆𒋢 | ||

| raḫ = 𒈛 ráḫ (raḫ₂) = 𒊏 |

riḫ = 𒈛 | ruḫ = 𒈛 | ||

| rak = 𒊩 | rik = 𒋆 |

ruk = 𒊿 | ||

| ram = 𒉘 rám (ram₂) = 𒀸 |

rem = 𒆸 rém (rem₂) = 𒀖 |

rim = 𒆸 |

rum = 𒀸 | |

| rin = 𒆸 |

||||

| rap = 𒊐 | rip = 𒆗 | |||

| raq = 𒊩 | req = 𒋆 | riq = 𒋆 ríq (riq₂) = 𒍮 |

ruq = 𒊿 | |

| ras = 𒆜 | res = 𒊕 | ris = 𒊕 | ||

| raš = 𒆜 ráš (raš₂) = 𒌇 |

reš = 𒊕 | riš = 𒊕 | ruš = 𒄭𒄊 | |

| rat = 𒋥 | rit = 𒈩 rít (rit₂) = 𒋥 |

|||

| raṭ = 𒋥 | riṭ = 𒈩 | ruṭ = 𒋥 | ||

| s- | ||||

| siu = 𒌣 | ||||

| sab = 𒉺𒅁 | sib = 𒈨 |

sub = 𒅢 súb (sub₂) = 𒁻 | ||

| sad = 𒆳 |

sed = 𒈻 séd (sed₂) = 𒋃 |

sid = 𒈻 síd (sid₂) = 𒋃 |

sud = 𒋤 | |

| sag = 𒊕 ság (sag₂) = 𒉺𒃶 |

seg = 𒋝 | sig = 𒋝 síg (sig₂) = 𒋠 |

sug = 𒆹 súg (sug₂) = 𒁻 | |

| saḫ = 𒆤 |

seḫ = 𒋚 séḫ (seḫ₂) = 𒆤 |

siḫ = 𒋚 |

suḫ = 𒈽 súḫ (suḫ₂) = 𒋦 | |

| sak = 𒊕 |

sik = 𒋝 sík (sik₂) = 𒋠 |

suk = 𒆹 | ||

| sal = 𒊩 |

sil = 𒋻 síl (sil₂) = 𒉣 |

sul = 𒂄 | ||

| sam = 𒌑 sám (sam₂) = |

sim = 𒉆 |

sum = 𒋧 | ||

| san = 𒊕 |

sin = 𒌍 |

sun = 𒁁 sún (sun₂) = 𒄢 | ||

| sap = 𒉺𒅁 |

sip = 𒈨 |

súp (sup₂) = 𒁻 | ||

| saq = 𒊕 | siq = 𒋝 | suq = 𒆹 | ||

| sar = 𒊬 sár (sar₂) = 𒊹 |

ser = 𒋤 sèr (ser₃) = 𒂡 |

sir = 𒋤 |

sur = 𒋩 súr (sur₂) = 𒊨 | |

| sas = 𒆠𒆗 | ses = 𒋀 | sis = 𒋀 | sus = 𒈽 sús (sus₂) = 𒈹 | |

| siš = 𒋀 | suš = 𒆪 | |||

| sat = 𒆳 | sít (sit₂) = 𒋃 | |||

| ṣ- | ṣab = 𒂟 | ṣib = 𒍦 ṣíb (ṣib₂) = 𒍨 |

||

| ṣaḫ = 𒉈 | ṣeḫ = 𒋚 ṣéḫ (ṣeḫ₂) = 𒉈 |

ṣiḫ = 𒋚 ṣíḫ (ṣiḫ₂) = 𒉈 | ||

| ṣak = 𒍠 | ||||

| ṣal = 𒉌 | ṣil = 𒉣 | |||

| ṣim = 𒍮 | ṣum = 𒍮 | |||

| ṣin = 𒌍 | ||||

| ṣap = 𒂟 | ṣip = 𒍦 | |||

| ṣar = 𒇡 |

ṣer = 𒈲 | ṣir = 𒈲 | ṣur = 𒀫 ṣúr (ṣur₂) = 𒈲 | |

| ṣiṣ = 𒁁 | ||||

| ś- | śig = 𒋠 | |||

| śik = 𒋠 | ||||

| śal = 𒊩 | ||||

| śim = 𒋆 śím (śim₂) = 𒉆 |

śum = 𒋳 śúm (śum₂) = 𒋧 | |||

| śín (śin₂) = 𒉆 | ||||

| śar = 𒊬 |

śur = 𒋩 śúr (śur₂) = 𒊨 | |||

| š- | šab = 𒉺𒅁 |

šeb = 𒈨 šéb (šeb₂) = 𒊒 |

šib = 𒈨 |

šub = 𒊒 šùb (šub₃) = 𒉺𒅁 |

| šad = 𒆳 |

šed = 𒋃 šèd (šed₃) = 𒉫 |

šid = 𒋃 |

šud = 𒋤 | |

| šag = 𒊕 |

šèg (šeg₃) = 𒀀𒀭 šeg₄ = 𒀀𒋙𒉀 |

šig = 𒋝 |

šug = 𒉻 | |

| šaḫ = 𒋚 |

šeḫ = 𒋚 | šiḫ = 𒋚 šíḫ (šiḫ₂) = 𒆤 |

šuḫ = 𒈽 šúḫ (šuḫ₂) = 𒋚 | |

| šak = 𒊕 šak₆ = 𒋝 |

šék (šek₂) = 𒋠 | šik = 𒋝 |

šuk = 𒉻 | |

| šal = 𒊩 |

šel = 𒋻 šel₄ = 𒊩 |

šil = 𒋻 |

šul = 𒂄 šùl (šul₂) = 𒁲 | |

| šam = 𒌑 |

šem = 𒋆 |

šim = 𒋆 ším (šim₂) = 𒉆 |

šum = 𒋳 | |

| šan = 𒉓 |

šen = 𒊿 |

šin = 𒊿 šín (šin₂) = 𒈫 |

šun = 𒊿𒊿 | |

| šap = 𒉺𒅁 šap₅ = 𒉺𒇻 |

šip = 𒈨 šìp (šip₃) = 𒉺𒅁 |

šup = 𒊒 | ||

| šaq = 𒊕 | šéq (šeq₂) = 𒋠 | šiq = 𒋝 |

šuq = 𒉻 | |

| šar = 𒊬 šár (šar₂) = 𒊹 |

šer = 𒋓 šér (šer₂) = 𒁍 |

šir = 𒋓 šír (šir₂) = 𒁍 |

šur = 𒋩 | |

| šas = 𒋀 | ||||

| šaṣ = 𒋀 | šeṣ = 𒋀 | šiṣ = 𒋀 | ||

| šaš = 𒋀 | šeš = 𒋀 |

šiš = 𒋀 šíš (šiš₂) = 𒋁 |

šuš = 𒌋 | |

| šat = 𒆳 šàt (šat₃) = 𒃻 |

šet = 𒋃 | šit = 𒋃 | šut = 𒋤 | |

| šaṭ = 𒆳 | šiṭ = 𒋃 | šuṭ = 𒋤 | ||

| šiz = 𒋀 | šuz = 𒋤 | |||

| t- | tab = 𒋰 |

teb = 𒁳 | tib = 𒁳 | tub = 𒁾 túb (tub₂) = 𒂀 |

| tad = 𒋺 | tid = 𒅎 | tud = 𒌅 túd (tud₂) = 𒉺𒍜 | ||

| tag = 𒋳 |

tèg (teg₃) = 𒋼 | tig = 𒄘 |

tug = 𒌇 túg (tug₂) = 𒌆 | |

| taḫ = 𒈭 |

tuḫ = 𒃮 / 𒂃 | |||

| tak = 𒋳 |

tik = 𒄘 tík (tik₂) = 𒉌 |

tuk = 𒌇 | ||

| tal = 𒊑 |

tel = 𒁁 | til = 𒁁 tíl (til₂) = 𒇯 |

tul = 𒌋𒌆 | |

| tam = 𒌓 |

tem = 𒁴 | tim = 𒁴 |

tum = 𒌈 túm (tum₂) = 𒁺 | |

| tan = 𒆗 |

ten = 𒋼 |

tin = 𒁷 tìn (tin₃) = 𒂆 |

tun = 𒄽 | |

| tap = 𒋰 | tep = 𒁳 | tip = 𒁳 | tup = 𒁾 túp (tup₂) = 𒂀 | |

| taq = 𒋳 |

tiq = 𒄘 tíq (tiq₂) = 𒉌 |

tuq = 𒌇 tùq (tuq₃) = 𒂁 | ||

| tar = 𒋻 |

ter = 𒌁 |

tir = 𒌁 |

tur = 𒌉 túr (tur₂) = 𒄙 | |

| tas = 𒌨 | tés (tes₂) = 𒌨 | tis = 𒁹 tís (tis₂) = 𒌨 |

||

| taṣ = 𒌨 | téṣ (tes₂) = 𒌨 | tíṣ (tis₂) = 𒌨 | ||

| taš = 𒌨 |

téš (teš₂) = 𒌨 | tiš = 𒁹 tíš (tiš₂) = 𒌨 |

tuš = 𒆪 | |

| tat = 𒋺 | ||||

| taz = 𒌨 | tiz = 𒁹 tíz (tiz₂) = 𒌨 | |||

| ṭ- | ṭab = 𒋰 |

ṭib = 𒁳 ṭíb (ṭib₂) = 𒄭 |

ṭub = 𒁾 ṭúb (ṭub₂) = 𒂀 | |

| ṭad = 𒋺 | ||||

| ṭaḫ = 𒈭 |

ṭuḫ = 𒂃 / 𒃮 | |||

| ṭak = 𒁖 | ṭug = 𒂁 | |||

| ṭuk = 𒂁 | ||||

| ṭal = 𒊑 | ṭil = 𒀸 ṭíl (ṭil₂) = 𒁁 |

ṭul = 𒇥 ṭùl (ṭul₃) = 𒇯 | ||

| ṭam = 𒁮 ṭám (ṭam₂) = 𒌓 |

ṭém (ṭem₂) = 𒁶 | ṭim = 𒁴 ṭím (ṭim₂) = 𒁶 |

ṭum = 𒌈 | |

| ṭan = 𒆗 | ṭin = 𒁷 | |||

| ṭap = 𒋰 | ṭep = 𒁳 | ṭip = 𒁳 | ṭup = 𒁾 ṭúp (ṭup₂) = 𒂀 | |

| ṭar = 𒋻 |

ṭer = 𒋛𒀀 ṭer₅ = 𒌁 |

ṭir = 𒋛𒀀 |

ṭur = 𒄙 | |

| ṭiš = 𒁹 | ||||

| ṭaṭ = 𒋺 | ||||

| w- | wuk = 𒈮 | |||

| wil = 𒅖 | ||||

| wan = 𒌋𒌋 | ||||

| war = 𒁇 |

wir = 𒄊| | |||

| waš = 𒈦 | wiš = 𒈨𒌍 | wuš = 𒈲 | ||

| z- | zab = 𒂟 | zeb = 𒍦 | zib = 𒍦 |

zub = 𒆛 zúb (zub₂) = 𒍦 |

| zid = 𒍣 zíd (zid₂) = 𒂠 |

||||

| zag = 𒍠 |

zig = 𒍨 |

zug = 𒆹 | ||

| zaḫ = 𒉈 |

ziḫ = 𒄗 | zuḫ = 𒅗 | ||

| zak = 𒍠 zák (zak₂) = 𒉺 |

zek = 𒍨 | zik = 𒍨 zík (zik₂) = 𒋝 |

zuk = 𒆹 | |

| zal = 𒉌 zál (zal₂) = 𒇡 |

zel = 𒉣 | zil = 𒉣 zíl (zil₂) = 𒋳 |

zul = 𒂄 | |

| zum = 𒍮 zúm (zum₂) = 𒊪 | ||||

| zap = 𒂟 záp (zap₂) = 𒆪 |

zip = 𒍦 | |||

| zaq = 𒍠 |

ziq = 𒍨 zíq (ziq₂) = 𒋝 |

zuq = 𒆹 | ||

| zar = 𒇡 |

zer = 𒆰 zèr (zer₃) = 𒈲 |

zir = 𒆰 |

zur = 𒀫 | |

| zis = 𒁁 | ||||

| zaz = 𒁁 | zez = 𒁁 | ziz = 𒁁 |

Numerals

[edit]The Sumerians used a base-60 numerical system. A number, such as "70", would be represented with the digit for "60" (𒁹) and the digit for "10" (𒌋): 𒁹𒌋. It's important to mention that the number for "60" is the same as the number for "1";[5] the reason this number isn't read as "11" is because of the order of the numbers: 60 then 10, not 10 then 60.

Usage

[edit](c. 2094–2047 BC)

NIN-a-ni..................... "his Lady",

SHUL-GI.................... "Shulgi"

NITAH KALAG-ga...... "the mighty man"

LUGAL URIMKI-ma... "King of Ur"

LUGAL ki-en-............... "King of Sum-"

-gi ki-URI-ke................. "-er and Akkad",

É-a-ni.......................... "her Temple"

mu-na-DU................... "he built"[5]

Cuneiform script was used in many ways in ancient Mesopotamia. Besides the well-known clay tablets and stone inscriptions, cuneiform was also written on wax boards.[59] One example from the 8th century BC was found at Nimrud. The wax contained toxic amounts of arsenic.[60] It was used to record laws, like the Code of Hammurabi. It was also used for recording maps, compiling medical manuals, and documenting religious stories and beliefs, among other uses. In particular it is thought to have been used to prepare surveying data and draft inscriptions for Kassite stone kudurru.[61][62] Studies by Assyriologists like Claus Wilcke[63] and Dominique Charpin[64] suggest that cuneiform literacy was not reserved solely for the elite but was common for average citizens.

According to the Oxford Handbook of Cuneiform Culture,[65] cuneiform script was used at a variety of literacy levels: average citizens needed only a basic, functional knowledge of cuneiform script to write personal letters and business documents. Citizens with a higher degree of literacy put the script to more technical use, listing medicines and diagnoses and writing mathematical equations. Scholars held the highest literacy level of cuneiform and mostly focused on writing as a complex skill and an art form.

Modern usage

[edit]Cuneiform is occasionally used nowadays as inspiration for logos.

-

Cuneiform ama-gi, literally "return to the mother", loosely translated as "liberty", is the logo of Liberty Fund.[66]

-

The central element of the GigaMesh Software Framework logo is the sign 𒆜 (kaskal) meaning "street" or "road junction".

Unicode

[edit]As of version 16.0, the following ranges are assigned to the Sumero-Akkadian Cuneiform script in the Unicode Standard:[67]

- U+12000–U+123FF (922 assigned characters) Cuneiform

- U+12400–U+1247F (116 assigned characters) Cuneiform Numbers and Punctuation

- U+12480–U+1254F (196 assigned characters) Early Dynastic Cuneiform

- In proposal phase Proto-cuneiform[68]

The final proposal for Unicode encoding of the script was submitted by two cuneiform scholars working with an experienced Unicode proposal writer in June 2004.[69] The base character inventory is derived from the list of Ur III signs compiled by the Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative of UCLA based on the inventories of Miguel Civil, Rykle Borger (2003) and Robert Englund. Rather than opting for a direct ordering by glyph shape and complexity, according to the numbering of an existing catalog, the Unicode order of glyphs was based on the Latin alphabetic order of their "last" Sumerian transliteration as a practical approximation. Once in Unicode, glyphs can be automatically processed into segmented transliterations.[70]

Corpus

[edit]

Numerous efforts have been made since the 19th century to create a corpus of known cuneiform inscriptions. In the 21st century, the Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative and Open Richly Annotated Cuneiform Corpus are two of the most significant projects.

List of major cuneiform tablet discoveries

[edit]| Location | Number of tablets | Initial discovery | Language |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nineveh | 20,000–24,000[71] | 1840 | Akkadian |

| Nippur | 60,000[71] | 1851 | |

| Girsu | 40,000–50,000[71] | 1877 | |

| Dūr-Katlimmu | 500[71] | 1879 | |

| Sippar | 60,000–70,000[72][71] | 1880 | Babylonian |

| Amarna | 382 | 1887 | Canaano-Akkadian |

| Nuzi | 10,000–20,000[71] | 1896 | Akkadian, Hurro-Akkadian |

| Assur | 16,000[73] | 1898 | Akkadian |

| Hattusa | 30,000[74] | 1906 | Hittite, Hurrian |

| Drehem | 100,000[71] | Sumerian | |

| Kanesh | 23,000[75] | 1925[note 2] | Akkadian |

| Ugarit | 1,500 | 1929 | Ugaritic, Hurrian |

| Persepolis | 15,000–18,000[76] | 1933 | Elamite, Old Persian |

| Mari | 20,000–25,000[71] | 1933 | Akkadian |

| Alalakh | 300[77] | 1937 | Akkadian, Hurro-Akkadian |

| Abu Salabikh | 500[71] | 1963 | Sumerian, Akkadian |

| Ebla | approx. 5,000[78] | 1974 | Sumerian, Eblaite |

| Nimrud | 244 | 1952 | Neo-Assyrian, Neo-Babylonian |

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ /kjuːˈniː.ɪfɔːrm/ kew-NEE-ih-form, /kjuːˈneɪ.ɪfɔːrm/[1][2] kew-NAY-ih-form, or /ˈkjuːnɪfɔːrm/[1] KEW-nih-form

- ^ Tablets from the site surfaced on the market as early as 1880, when three tablets made their way to European museums. By the early 1920s, the number of tablets sold from the site exceeded 4,000. While the site of Kültepe was suspected as the source of the tablets, and the site was visited several times, it was not until 1925 when Bedřich Hrozný corroborated this identification by excavating tablets from the fields next to the tell that were related to tablets already purchased.

References

[edit]This article contains one or more duplicated citations. The reason given is: DuplicateReferences detected: (May 2025)

|

- ^ a b "cuneiform". Oxford Dictionaries.

- ^ Cuneiform: Irving Finkel & Jonathan Taylor bring ancient inscriptions to life. The British Museum. June 4, 2014.

- ^ Jagersma, Abraham Hendrik (2010). A descriptive grammar of Sumerian (PDF) (Thesis). Faculty of the Humanities, Leiden University. p. 15.

In its fully developed form, the Sumerian script is based on a mixture of logographic and phonographic writing. There are basically two types of signs: word signs, or logograms, and sound signs, or phonograms.

- ^ a b c Kimball, Sara E.; Slocum, Jonathan. "Hittite Online". The University of Texas at Austin Linguistics Research Center. Early Indo-European OnLine. 2 The Cuneiform Syllabary.

Hittite is written in a form of the cuneiform syllabary, a writing system in use in Sumerian city-states in Mesopotamia by roughly 3100 B.C.E. and used to write a number of languages in the ancient Near East until the first century B.C.E.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Olson, David R.; Torrance, Nancy (2009). The Cambridge Handbook of Literacy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-86220-2.

- ^ "The origins of writing". The British Museum. Archived from the original on March 11, 2022. Retrieved May 10, 2022.

- ^ Huehnergard, John (2004). "Akkadian and Eblaite". Cambridge Encyclopedia of the World's Ancient Languages. Cambridge University Press. p. 218. ISBN 978-0-521-56256-0.

Connected Akkadian texts appear c. 2350 and continue more or less uninterrupted for the next two and a half millennia...

- ^ Archi, Alfonso (2015). "How the Anitta text reached Hattusa". Saeculum: Gedenkschrift für Heinrich Otten anlässlich seines 100. Geburtstags. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ISBN 978-3-447-10365-7.

The existence of the Anitta text demonstrates that there was not a sudden and total interruption in writing but a phase of adaptation to a new writing.

- ^ a b Hunger, Hermann, and Teije de Jong, "Almanac W22340a from Uruk: The latest datable cuneiform tablet.", Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und vorderasiatische Archäologie 104.2, pp. 182–194, 2014

- ^

- Hommel, Fritz (1897). The Ancient Hebrew Tradition as Illustrated by the Monuments. Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. p. 29.

It is necessary here to remark, that the application of the term "Assyriology," as it is now generally used, to the study of the cuneiform inscriptions, is not quite correct; indeed it is actually misleading.

- Meade, Carroll Wade (1974). Road to Babylon: Development of U.S. Assyriology. Brill. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-90-04-03858-5.

The term Assyriology is derived from these people, but it is very misleading.

- Daneshmand, Parsa (2020). "Chapter 14 Assyriology in Iran?". Perspectives on the History of Ancient Near Eastern Studies. Penn State University Press. p. 266. doi:10.1515/9781646020898-015. ISBN 978-1-64602-089-8. S2CID 236813488.

The term "Assyriology" is itself problematic because it covers a broad range of topics.

Charpin, Dominique (2018). "Comment peut-on être assyriologue ? : Leçon inaugurale prononcée le jeudi 2 octobre 2014". Comment peut-on être assyriologue ?. Leçons inaugurales (in French). Collège de France. ISBN 978-2-7226-0423-0 – via OpenEdition Books.Dès lors, le terme assyriologue est devenu ambigu : dans son acception large, il désigne toute personne qui étudie des textes notés dans l'écriture cunéiforme.

- Hommel, Fritz (1897). The Ancient Hebrew Tradition as Illustrated by the Monuments. Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. p. 29.

- ^ a b c "Cuneiform Tablets: Who's Got What?", Biblical Archaeology Review, 31 (2), 2005, archived from the original on July 15, 2014

- ^ Streck, Michael P. (2010). "Großes Fach Altorientalistik. Der Umfang des keilschriftlichen Textkorpus". Mitteilungen der Deutschen Orientgesellschaft 142 (PDF) (in German). pp. 57–58.

- ^ a b "Image gallery: tablet / cast". British Museum.

- ^ a b c "Beginning in the pottery-phase of the Neolithic, clay tokens are widely attested as a system of counting and identifying specific amounts of specified livestock or commodities. The tokens, enclosed in clay envelopes after being impressed on their rounded surface, were gradually replaced by impressions on flat or plano-convex tablets, and these in turn by more or less conventionalized pictures of the tokens incised on the clay with a reed stylus. The transition to writing was complete W. Hallo; W. Simpson (1971). The Ancient Near East. New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich. p. 25.

- ^ Adkins 2003, p. 47.

- ^ [1] Bennison-Chapman, Lucy E. "Reconsidering 'Tokens': The Neolithic Origins of Accounting or Multifunctional, Utilitarian Tools?." Cambridge Archaeological Journal 29.2 (2019): 233–259.

- ^ Overmann, Karenleigh A. The Material Origin of Numbers: Insights from the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, Piscataway, New Jersey, US: Gorgias Press, 2019

- ^ Denise Schmandt-Besserat, "An Archaic Recording System and the Origin of Writing." Syro Mesopotamian Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 1–32, 1977

- ^ a b c d e f g Walker, C. (1987). Reading The Past Cuneiform. British Museum. pp. 7-6.

- ^ Denise Schmandt-Besserat, An Archaic Recording System in the Uruk-Jemdet Nasr Period, American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 83, no. 1, pp. 19–48, (Jan. 1979)

- ^ Walker, C. (1987). Reading The Past Cuneiform. British Museum. p. 9.

- ^ [2] Robert K. Englund, "Proto-Cuneiform Account-Books and Journals", in Michael Hudson and Cornelia Wunsch, eds., Creating Economic Order: Record-keeping, Standardization and the Development of Accounting in the Ancient Near East (CDL Press: Bethesda, Maryland, USA) pp. 23–46, 2004

- ^ Green, M. and H. J. Nissen (1987). Zeichenliste der Archaischen Texte aus Uruk. ATU 2. Berlin

- ^ Englund, R. K. (1998). "Texts from the Late Uruk Period". In: Mesopotamien: Späturuk-Zeit und Frühdy- nastische Zeit (Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis 160/1). Ed. by P. Attinger and M. Wäfler. Fribourg, Switzerland / Göttingen, 15–217

- ^ [3] Born, L., & Kelley, K. (2021). A Quantitative Analysis of Proto-Cuneiform Sign Use in Archaic Tribute. Cuneiform Digital Library Bulletin, 006

- ^ a b Walker, C. (1987). Reading The Past Cuneiform. British Museum. p. 14.

- ^ Monaco, Salvatore F. "PROTO-CUNEIFORM AND SUMERIANS." Rivista Degli Studi Orientali, vol. 87, no. 1/4, 2014, pp. 277–282

- ^ Walker, C. (1987). Reading The Past Cuneiform. British Museum. p. 12.

- ^ a b Walker, C. (1987). Reading The Past Cuneiform. British Museum. pp. 11-12.

- ^ Walker, C. (1987). Reading The Past Cuneiform. British Museum. pp. 11-12.

This syllabic stage of the script's development is known from a group of texts from Ur corresponding to the archaeological levels Early Dynastic I-II (c. 2800 BC). In these texts we find the first identifiable use of purely phonetic elements and grammar [...].

- ^ Walker, C. (1987). Reading The Past Cuneiform. British Museum. p. 13.

- ^ "Proto-cuneiform tablet". www.metmuseum.org.

- ^ Iorwerth Eiddon Stephen Edwards, et al., The Cambridge Ancient History (3rd ed. 1970) pp. 43–44.

- ^ Barraclough, Geoffrey; Stone, Norman (1989). The Times Atlas of World History. Hammond. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-7230-0304-5.

- ^ a b c d Foxvog, Daniel A. Introduction to Sumerian grammar (PDF). p. 12. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 3, 2017

- ^ Mémoires. Mission archéologique en Iran. 1900. p. 53.

- ^ Walker, C. Reading The Past: Cuneiform. pp. 16–17.

- ^ a b c Khačikjan, Margaret. The Elamite language (1998). p. 1.

- ^ Peter Daniels and William Bright (1996)

- ^ Reiner, Erica (2005)

- ^ a b Козлова, Н. В.; Касьян, А. С.; Коряков, Ю. Б. (2010). "Клинопись". Языки мира: Древние реликтовые языки Передней Азии (in Russian): 197–222.

- ^ For the original inscription: Rawlinson, H. C. Cuneiform inscriptions of Western Asia (PDF). p. 3, column 2, line 98. For the transliteration in Sumerian an-szar2-du3-a man kur_ an-szar2{ki}: "CDLI-Archival View". cdli.ucla.edu. For the translation: Luckenbill, David. Ancient Records of Assyria and Babylonia Volume II (PDF). p. 297. For the Assyrian pronunciation: Quentin, A. (1895). "Inscription Inédite du Roi Assurbanipal: Copiée Au Musée Britannique le 24 Avril 1886". Revue Biblique (1892-1940). 4 (4): 554. ISSN 1240-3032. JSTOR 44100170.

- ^ Frye, Richard N. "History of Mesopotamia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved December 11, 2020.

The use of cuneiform in government documents ceased sometime during the Achaemenian period, but it continued in religious texts until the 1st century of the Common era.

- ^ Geller, Marckham (1997). "The Last Wedge". Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und vorderasiatische Archäologie. 87 (1): 43–95. doi:10.1515/zava.1997.87.1.43. S2CID 161968187.

- ^ Windfuhr, G. L.: "Notes on the old Persian signs", page 1. Indo-Iranian Journal, 1970.

- ^ Schmitt, R. (2008), "Old Persian", in Roger D. Woodard (ed.), The Ancient Languages of Asia and the Americas (illustrated ed.), Cambridge University Press, p. 77, ISBN 978-0-521-68494-1

- ^ a b Watkins, Lee; Snyder, Dean (2003), The Digital Hammurabi Project (PDF), The Johns Hopkins University, archived (PDF) from the original on July 14, 2014,

Since the decipherment of Babylonian cuneiform some 150 years ago museums have accumulated perhaps 300,000 tablets written in most of the major languages of the Ancient Near East – Sumerian, Akkadian (Babylonian and Assyrian), Eblaite, Hittite, Persian, Hurrian, Elamite, and Ugaritic. These texts include genres as variegated as mythology and mathematics, law codes and beer recipes. In most cases these documents are the earliest exemplars of their genres, and cuneiformists have made unique and valuable contributions to the study of such moderns disciplines as history, law, religion, linguistics, mathematics, and science. In spite of continued great interest in mankind's earliest documents it has been estimated that only about 1/10 of the extant cuneiform texts have been read even once in modern times. There are various reasons for this: the complex Sumero/Akkadian script system is inherently difficult to learn; there is, as yet, no standard computer encoding for cuneiform; there are only a few hundred qualified cuneiformists in the world; the pedagogical tools are, in many cases, non-optimal; and access to the widely distributed tablets is expensive, time-consuming, and, due to the vagaries of politics, becoming increasingly difficult.

- ^ [4]Sayce, Rev. A. H., "The Archaeology of the Cuneiform Inscriptions", Second Edition-revised, Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, London, Brighton, New York, 1908 (Reprint – ISBN 978-1-108-08239-6)

- ^ "DPa". Livius. April 16, 2020. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

- ^ "XPe". Livius. September 24, 2020. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

- ^ Gutherz, Gai; Gordin, Shai; Sáenz, Luis; Levy, Omer; Berant, Jonathan (May 2, 2023). Kearns, Michael (ed.). "Translating Akkadian to English with neural machine translation". PNAS Nexus. 2 (5) pgad096. doi:10.1093/pnasnexus/pgad096. ISSN 2752-6542. PMC 10153418. PMID 37143863.

- ^ "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- ^ "Antiochus cylinder". British Museum.

- ^ Wallis Budge, Ernest Alfred (1884). Babylonian Life and History. Religious Tract Society. p. 94.

- ^ Cf. The Cylinder of Antiochus I from the Ezida temple in Borsippa (BM 36277), p.4 by M. Stol and R.J. van der Spek and Antiochus I 01 by The Royal Inscriptions of Babylonia online (RIBo) Project.

The transliteration here differs slightly from these sources by rendering the determinative for male personal names 𒁹 with the Sumerian reading of the sign DIŠ, whereas it is more commonly transcribed with the conventional letter M today. The spellings 𒂍𒊕𒅍 (É.SAG.ÍL) and 𒂍𒍣𒁕 (É.ZI.DA) can also be read phonetically in Akkadian (as they are in the second source), because the names themselves have been borrowed into Akkadian with their Sumerian pronunciations. Conversely, the sign 𒆗, which may have the phonetic value dan in Akkadian, was nevertheless originally a Sumerian logogram KAL 'strong'. Finally, 𒅇 (ù) was the word for 'and' not only in Akkadian, but also in Sumerian. - ^ Kudrinski, Maksim. "Hittite heterographic writings and their interpretation" Indogermanische Forschungen, vol. 121, no. 1, pp. 159–176, 2016

- ^ Veldhuis, Niek (September 22, 2011), Radner, Karen; Robson, Eleanor (eds.), "Levels of Literacy", The Oxford Handbook of Cuneiform Culture, Oxford University Press, pp. 68–89, doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199557301.013.0004, ISBN 978-0-19-955730-1, retrieved March 4, 2025

- ^ a b c d Borger 2004, pp. 245–539.

- ^ Zimmermann, Lynn-Salammbô, "Knocking on Wood: Writing Boards in the Kassite Administration", Journal of Ancient Near Eastern History, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 177-237, 2023

- ^ Cammarosano, Michele, Katja Weirauch, Feline Maruhn, Gert Jendritzki, and Patrick L. Kohl, "They Wrote on Wax. Wax Boards in the Ancient Near East", Mesopotamia, vol. 54, pp. 121‒180, 2019

- ^ Zimmermann, Lynn-Salammbô. "Wooden Wax-Covered Writing Boards as Vorlage for kudurru Inscriptions in the Middle Babylonian Period" Journal of Ancient Near Eastern History, 2022

- ^ "The World's Oldest Writing". Archaeology. 69 (3). May 2016. Archived from the original on April 27, 2016. Retrieved September 18, 2016 – via Virtual Library of Virginia.

- ^ Wilcke, Claus (2000). Wer las und schrieb in Babylonien und Assyrien. München: Verlag der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. ISBN 978-3-7696-1612-5.

- ^ Charpin, Dominique. 2004. "Lire et écrire en Mésopotamie: Une affaire dé spécialistes?" Comptes rendus de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres: 481–501.

- ^ Veldhuis, Niek (2011). Radner, Karen; Robson, Eleanor (eds.). "Levels of Literacy". The Oxford Handbook of Cuneiform Culture. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199557301.001.0001. hdl:10261/126580. ISBN 978-0-19-955730-1.

- ^ "Our Logo | Liberty Fund". libertyfund.org. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

The cuneiform inscription that serves as Liberty Fund's logo and as a design element in our books is the earliest-known written appearance of the word 'freedom' (amagi), or 'liberty'. It is taken from a clay document written about 2300 B.C. in the Sumerian city-state of Lagash.

- ^ [5]"Cuneiform and Hieroglyphs", in The Unicode® Standard Version 16.0 – Core Specification, September 10, 2024

- ^ [6] Robin Leroy, Anshuman Pandey, and Steve Tinney, "Archaic cuneiform numerals", L2/24-210R, 2024-10-23

- ^ Everson, Michael; Feuerherm, Karljürgen; Tinney, Steve (June 8, 2004). "Final proposal to encode the Cuneiform script in the SMP of the UCS".

- ^ Gordin S, Gutherz G, Elazary A, Romach A, Jiménez E, Berant J, et al. (2020) "Reading Akkadian cuneiform using natural language processing". PLoS ONE 15(10): e0240511. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240511

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Bertman, Stephen (2005). Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-518364-1.