Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Phantom cat

View on Wikipedia

This article may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. (May 2018) |

Phantom cats, also known as alien big cats (ABCs), are large felids which allegedly appear in regions outside their indigenous range. Sightings, tracks, and predation have been reported in a number of countries including Australia, Canada, China, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, India, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, New Zealand, Spain, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States. When confirmed, they are typically explained as exotic pets or escapees from private zoos.

Australia

[edit]Sightings of exotic big cats in Australia began during the 19th century. It is generally thought that sightings may be attributed to escaped exotic circus animals such as Matthew St Leon's touring circus in the 1870s and large cats brought back as pets by soldiers.[1] In one such example, in 1924, a puma and a jaguar both escaped from the Perry Brothers circus while traveling from St Arnaud, Victoria by train when their carriage's wall collapsed. The jaguar was captured after stunning itself, and the Puma later shot.[2]

The New South Wales State Government reported in 2003 that "more likely than not" there were a number of exotic big cats living deep in the bushlands near Sydney.[3]

Phantom cats reported in Australia include

- The Blue Mountains panther (also called the Penrith panther or Lithgow panther), reported in the mountains west of Sydney since the early 20th century.

- The Grampians Puma, which a 1970s study by Deakin University could not be definitively demonstrated based on available evidence, however, that the probability of big cats in the area is “beyond reasonable doubt".[4]

- The Sunshine Coast big cat, reported in the Sunshine Coast, Queensland, since early in the 19th century.[5][6] These claims have been met with skepticism.[6]

- The Gipplands phamton cat.[7]

- The Tantanoola Tiger, believed to have been shot on 25 August 1895, by Tom Donovian and identified as an Assyrian wolf; although no such species appears to exist. It was stuffed and remains on display in the Tantanoola Hotel.[8][9]

- The Tasmanian Panther, reported in Tasmania since the 19th century. The novel Dusk by Robbie Arnott is based on this folklore.

- The Ourimbah panther, reported in the Ourimbah State Forest of New South Wales.

- The Nannup tiger, in Nannup, Western Australia, subject of a song by Matt Taylor - sometimes instead said to be a Thylacine.

- The Emmaville Panther, in the New England region of New South Wales.

Bulgaria

[edit]In June of 2025, sightings of a large black cat or panther were reported in the eastern city of Shumen.[10] Later, sightings of what was assumed to be the same animal were reported in the towns of Giurgiu and Năsturelu in Romania.[11] Although no hard evidence has been documented, one hypothesis is that it escaped from captivity, perhaps from an illegal, private zoo owned by criminals,[12] or migrated from Hungary or Serbia.[13] Experts have suggested that evidence of tracks could be attributed to large dogs.[14]

China

[edit]The blue, or Maltese, tiger, the former name taken from the common color terminology for domestic cats, is a purported color morph of the South China tiger, with sightings in Myanmar, China, and the Korean Peninsula. It is speculated that while the color morph may have theoretically existed, the severe historical bottlenecking of tiger populations makes it unlikely for the genotype to remain in extant populations.

Denmark

[edit]In 1995, a big cat usually described as a lion (but sometimes as a lynx) was dubbed the "beast of Funen" by numerous eyewitnesses.[15] There was an earlier big cat sighting from 1982 in southern Jutland.[15]

Finland

[edit]A supposed lion moved around Ruokolahti near the Finnish-Russian border in June–August 1992. There were multiple sightings. Tracks were identified by a government biologist as a big feline not native to Finland. The biologist was given police powers to capture or shoot the lion by the Ministry of the Interior. Border guards participated in the hunt. The last reported sightings were in Russia and there were reports that the lion was seen by Finnish border guards[16] and that lion tracks were found in the raked sand field used by Russian border guards to detect crossings. The lion was never captured and the incidents have never been explained. One possible explanation could have been a railway accident of a circus train in Russia, from which some animals escaped.[17][18][19]

India

[edit]The pogeyan is a large grey feline known to local people living in the Western Ghats, India. Its name is derived from the local dialect, and means 'cat that comes and goes like the mist'.[20]

Luxembourg

[edit]In 2009, a black panther was allegedly spotted in the industrial area of Bommelscheuer near Bascharage.[21] When police came, the panther was gone. In the following couple of days, the panther was spotted all over the country. For a while it was alleged that a panther had escaped a nearby zoo (Amnéville), but the zoo later denied that any panther was missing. A couple of days after the Bascharage incident, it also was mentioned that although the police did not find a panther, they did find an unusually large house cat.[22]

The Netherlands

[edit]In 2005, a black cougar was allegedly spotted on several occasions in a wildlife preserve,[23] but the animal, nicknamed Winnie, was later identified as an unusually large crossbreed between a domestic cat and a wildcat.[24]

New Zealand

[edit]Since the late 1990s, big cat sightings have been reported in widely separated parts of New Zealand, in both the North[25] and South Islands.[citation needed] There have been several unverified panther sightings in Mid-Canterbury near Ashburton and in the nearby foothills of the Southern Alps,[26][27] but searches conducted there in 2003 by the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry found no corroborating physical evidence.[25]

United Kingdom

[edit]Since the 1960s, there have been many alleged sightings of big cats across Great Britain.[28] A 15-month survey conducted in 2003–2004 by the British Big Cats Society gave the following regional breakdown, based on 2,052 sightings: South West 21%, South East 16%, East Anglia 12%, Scotland 11%, and West Midlands 9%.[29] Since 1903, a number of exotic cats, all of which are thought to have escaped from captivity, have been killed or captured.[30][31][32][33]

United States

[edit]Phantom cat sightings in the United States should not be confused with sightings of jaguars in their native range in the states of Arizona and New Mexico (while early records of North American jaguars show much wider distribution as far as Monterey), or of cougars recolonizing the extirpated eastern cougar's former range.

-

Distribution of jaguars; pink indicates former range.

-

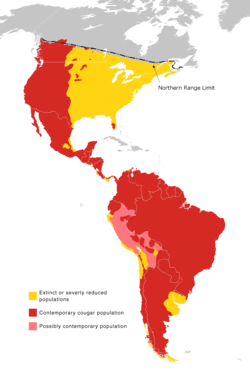

Distribution of cougars; yellow indicates former range. The lower 48 US states fall into the native range.

Connecticut

[edit]In 1939, a panther-like creature called the "glawackus" was sighted in Glastonbury, Connecticut. It became a national sensation, and sporadic sightings of it across Connecticut continued into the 1960s.[34]

Delaware

[edit]There have been reported sightings of a mountain lion in the northern Delaware forests since the late 1990s. The Delaware Division of Fish and Wildlife believes there may be more than one mountain lion in Delaware and that they originate from animals released from captivity.[35]

Hawaii

[edit]In December 2002, sightings of a big cat increased in numbers in the Kula (upcountry) area, and the Division of Forestry and Wildlife requested the help of big cat wildlife biologists William van Pelt and Stan Cunningham of the Arizona Game and Fish Department. Van Pelt and Cunningham believed that the cat was probably a large feline, such as a leopard, jaguar, or cougar.[36][37] No big cat was detected by traps, infrared cameras, or professional trackers. A fur sample was obtained in 2003, but DNA analysis was inconclusive. The state's hunt for the cat was suspended in late November 2003, after three weeks without sightings.[38] Utah State University professor and wildlife biologist Robert Schmidt expressed strong doubts about the cat's existence,[39] likening it to the Loch Ness monster.[40]

Massachusetts

[edit]MassWildlife has confirmed two cases of a mountain lion's presence in Massachusetts.[41] There have been numerous other reports of sightings, as well as alleged photographs, but these remain unconfirmed by state wildlife officials.[42][43]

North Carolina

[edit]Black panthers and other large non-indigenous cats have been sighted for many years in the vicinity of Oriental, North Carolina. Accounts from locals and visitors alike have been documented in the local papers.[44]

Explanations for Europe's Phantom Cats

[edit]

In Europe, escaped exotic wildcats have been caught both dead and alive by people of Great Britain. DNA testing also helped in the process of finding out what the animals could be, proving them to actually be exotic wildcats. In the 1970s, circus owner Mary Chipperfield allegedly released her pet mountain lions into the Moorlands of Great Britain after her circus shut down. A while later, people released their exotic animals into the woods after a ban on large exotic predators took place. People have taken pictures, killed and have even captured the animals alive. Exotic wildcat species that have been caught in Great Britain include:

Another confirmed explanation is that the phantom cats are actually large stray or hybrid cats since some stray cats hybridize with the native Scottish Wildcat and the hybrids are larger than a purebred cat. The Scottish Kellas Cat is the result of hybridization of both domestic and wildcats, and a now mounted specimen matches the description of the British Black Cats: a large, robust body with black fur and small ears.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Busby, Ellie (12 June 2025). "It's one of Sydney's favourite urban legends. But could it be real?". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 12 September 2025.

- ^ "Puma Escapes". Gippsland Times. 23 June 1924. Retrieved 12 September 2025.

- ^ Eamonn Duff (2 November 2003). "Big cats not a tall tale". The Sun-Herald. Retrieved 9 February 2010.

- ^ Henry, John; Deakin University; Faculty of Education (2001). Pumas in the Grampians mountains: a compelling case?; an updated report of the Deakin Puma Study. Geelong, Vic.: Deakin University. OCLC 224010721.

- ^ "Men claim evidence of 'panther like' cat in Qld bush". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 14 January 2009. Archived from the original on 13 February 2009. Retrieved 15 January 2009.

- ^ a b "Cold water poured on 'big cat' claims". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 14 January 2009. Archived from the original on 13 February 2009. Retrieved 15 January 2009.

- ^ "Big cat sightings and theories". Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 13 November 2007.

- ^ "Tantanoola". Wattle Range Council. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 31 May 2007.

- ^ "Millicent". Sydney Morning Herald. 8 February 2004.

- ^ "Bulgaria searches for elusive and dangerous black panther near Shumen". euronews. 24 June 2025. Retrieved 4 July 2025.

- ^ "The mystery of the black panther continues. An expert from Africa has been brought in to search for it". spotmedia.ro. 3 July 2025. Retrieved 4 July 2025.

- ^ "Fact-checking claims about the 'panther' on the loose in Bulgaria". euronews. 25 June 2025. Retrieved 4 July 2025.

- ^ "Panther in Shumen, Bulgaria May Have Migrated from Hungary, Say Experts - Novinite.com - Sofia News Agency". www.novinite.com. Retrieved 4 July 2025.

- ^ "Shumen's Black Panther Mystery Busted? Experts Say It's Just a Giant Dog - Novinite.com - Sofia News Agency". www.novinite.com. Retrieved 4 July 2025.

- ^ a b Wegner, Willy. "The Beast of Funen". Skepticreport.com. Archived from the original on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 20 December 2009.

- ^ "Ruokolahden leijona: Havaintoja salattiin 20 vuotta - Kotimaa". IltaSanomat.fi (in Finnish). Archived from the original on 18 October 2015. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- ^ "Elvi-leijonasta puhutaan yhä". Imatralainen.fi (in Finnish). 19 May 2011. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- ^ Liukkonen, Mauri (28 June 2014). "Ruokolahden leijona oli totta". SavonSanomat.fi (in Finnish). Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- ^ "Ruokolahden leijona". Ruokolahti.fi (in Finnish). Archived from the original on 23 August 2016. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- ^ Naish, D. "The Pogeyan, a new mystery cat". ScienceBlogs.com. Retrieved 19 January 2009.

- ^ "Schwarzer Panther auf Bommelscheuer". Archived from the original on 28 September 2022. Retrieved 9 March 2010.

- ^ "Viel Tamtam um eine schwarze Katze" (in German). Wort.lu. 26 October 2009. Archived from the original on 29 October 2009. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- ^ (in Dutch) Massale belangstelling voor poemajacht("Massive interest in cougar hunting")

- ^ (in Dutch) 'Poema' Winnie ontmaskerd Archived 10 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine ("'Puma' Winnie unmasked")

- ^ a b "MAF staff, wildlife experts hunt big black cat in vain". The New Zealand Herald. 9 October 2003. Retrieved 28 July 2009.

- ^ "An unsolved mystery". Ashburton Guardian. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- ^ Sandys, Susan (8 December 2009). "Bid to capture black panther". Ashburton Guardian. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 8 February 2010.

- ^ "More big cats recorded". BBC News. 28 January 2002. Retrieved 9 February 2010.

- ^ "Big Cat evidence gets stronger, as society calls for government study". British Big Cats Society. Retrieved 9 February 2010.

- ^ Rebecca Morelle (25 April 2013). "'Big cat' Canadian lynx was on the loose in UK in 1903". BBC News. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- ^ Chris Smith. "Felicity the Puma". www.scotcatsonline.fr. Retrieved 2 June 2012.

- ^ Chris Smith. "Second Scottish Puma". www.scotcatsonline.fr. Retrieved 2 June 2012.

- ^ O'Neill, Sean (9 May 2001). "The Beast of Cricklewood is caged". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ^ Engl, New; Legends. "Podcast 100 – Hunting Glastonbury's Glawackus – New England Legends". Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ Cpt. Robert Hutchins (26 February 2011). "Delaware Cougar Confirmations". cougarnet.org. Archived from the original on 11 August 2014. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- ^ "Status Report on the Olinda, Maui Mystery Cat". state.hi.us. Archived from the original on 29 July 2013.

- ^ Kubota, Gary (25 October 2003). "Expert thinks big cat is dangerous". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Retrieved 10 December 2008.

- ^ Hurley, Timothy (22 November 2003). "State suspends hunt for Maui cat". The Honolulu Advertiser. Retrieved 10 December 2008.

- ^ Schmidt, Robert (4 August 2003). "Forget catching ghost cat". The Honolulu Advertiser. Archived from the original on 25 April 2006. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ Hurley, Timothy (30 November 2003). "For Maui, it was year of the cat". The Honolulu Advertiser. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2008.

- ^ Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife (13 September 2017). "Are there Mountain Lions in Massachusetts?". Mass.gov. Archived from the original on 13 September 2017. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

There are two records of Mountain Lions in Massachusetts that meet the evidence requirements...

- ^ Bellow, Heather (15 December 2018). "Are the mountain lion sightings in Monterey for real?". The Berkshire Eagle. Pittsfield, Massachusetts: New England Newspapers Inc. Archived from the original on 3 August 2019. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

Reports of mountain lions have gotten some mileage lately throughout these rural hills, with possible sightings, and on occasion, some worry about the safety of people and animals.

- ^ Graham, George (8 August 2017). "Facebook photo reignites debate about mountain lions in Massachusetts". MassLive. Massachusetts: Advance Local. Archived from the original on 3 August 2019. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

A photo of a big cat sitting on the banks of the Housatonic River, taken late last month and posted on Facebook, has sparked lively debate, with many claiming it to be a mountain lion -- even as the photographer and state wildlife officials say otherwise.

- ^ Aydelette, Jeff (17 November 2011). "Most say panthers exist". The County Compass. Bayboro, North Carolina. Archived from the original on 17 October 2014. Retrieved 6 January 2015.