Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Polykleitos

View on WikipediaPolykleitos (/ˌpɔːliˈklaɪtoʊs/; Ancient Greek: Πολύκλειτος) was an ancient Greek sculptor, active in the 5th century BCE. Alongside the Athenian sculptors Pheidias, Myron and Praxiteles, he is considered as one of the most important sculptors of classical antiquity.[1] The 4th century BCE catalogue attributed to Xenocrates (the "Xenocratic catalogue"), which was Pliny's guide in matters of art, ranked him between Pheidias and Myron.[2] He is particularly known for his lost treatise, the Canon of Polykleitos (a canon of body proportions), which set out his mathematical basis of an idealised male body shape.

Key Information

None of his original sculptures are known to survive, but many marble works, mostly Roman, are believed to be later copies.

Name

[edit]

His Greek name was traditionally Latinized Polycletus, but is also transliterated Polycleitus (Ancient Greek: Πολύκλειτος [polýkleːtos], "much-renowned") and, due to iotacism in the transition from Ancient to Modern Greek, Polyklitos or Polyclitus. He is called Sicyonius (lit. "The Sicyonian", usually translated as "of Sicyon")[3] by Latin authors including Pliny the Elder and Cicero, and Ἀργεῖος (lit. "The Argive", trans. "of Argos") by others like Plato and Pausanias. He is sometimes called the Elder, in cases where it is necessary to distinguish him from his son, who is regarded as a major architect but a minor sculptor.

Early life and training

[edit]As noted above, Polykleitos is called "The Sicyonian" by some authors, all writing in Latin, and who modern scholars view as relying on an error of Pliny the Elder in conflating another more minor sculptor from Sikyon, a disciple of Phidias, with Polykleitos of Argos. Pausanias is adamant that they were not the same person, and that Polykleitos was from Argos, in which city state he must have received his early training,[a] and a contemporary of Phidias (possibly also taught by Ageladas).

Works

[edit]

Polykleitos's figure of an Amazon for Ephesus was admired, while his colossal gold and ivory statue of Hera which stood in her temple—the Heraion of Argos—was favourably compared with the Olympian Zeus by Pheidias. He also sculpted a famous bronze male nude known as the Doryphoros ("Spear Bearer"), which survives in the form of numerous Roman marble copies. Further sculptures attributed to Polykleitos are the Discophoros ("Discus-bearer"), Diadumenos ("Youth tying a headband")[4] and a Hermes at one time placed, according to Pliny, in Lysimachia (Thrace). Polykleitos's Astragalizontes ("Boys Playing at Knuckle-bones") was claimed by the Emperor Titus and set in a place of honour in his atrium.[5] Pliny also mentions that Polykleitos was one of the five major sculptors who competed in the fifth century B.C. to make a wounded Amazon for the temple of Artemis; marble copies associated with the competition survive.[6]

Diadumenos

[edit]The statue of Diadumenos, also known as Youth Tying a Headband is one of Polykleitos's sculptures known from many copies. The gesture of the boy tying his headband represents a victory, possibly from an athletic contest. "It is a first-century A.D. Roman copy of a Greek bronze original dated around 430 B.C."[4] Polykleitos sculpted the outline of his muscles significantly to show that he is an athlete. "The thorax and pelvis of the Diadoumenos tilt in opposite directions, setting up rhythmic contrasts in the torso that create an impression of organic vitality. The position of the feet poised between standing and walking give a sense of potential movement. This rigorously calculated pose, which is found in almost all works attributed to Polykleitos, became a standard formula used in Greco-Roman and, later, western European art."[4]

Doryphoros

[edit]Another statue created by Polykleitos is the Doryphoros, also called the Spear bearer. It is a typical Greek sculpture depicting the beauty of the male body. "Polykleitos sought to capture the ideal proportions of the human figure in his statues and developed a set of aesthetic principles governing these proportions that was known as the Canon or 'Rule'.[7] He created the system based on mathematical ratios. "Though we do not know the exact details of Polykleitos’s formula, the end result, as manifested in the Doryphoros, was the perfect expression of what the Greeks called symmetria.[7] On this sculpture, it shows somewhat of a contrapposto pose; the body is leaning most on the right leg. The Doryphoros has an idealized body, contains less of naturalism. In his left hand, there was once a spear, but if so it has since been lost. The posture of the body shows that he is a warrior and a hero.[4][7] Indeed, some have gone so far as to suggest that the figure depicted was Achilles, on his way to the Trojan War, as a similar depiction of Achilles carrying a shield is seen on a vase painted by the Achilles Painter at around the same time.[8]

Style

[edit]

Polykleitos, along with Phidias, created the Classical Greek style. Although none of his original works survive, literary sources identifying Roman marble copies of his work allow reconstructions to be made. Contrapposto, a pose that visualizes the shifting balance of the body as weight is placed on one leg, was a source of his fame.

The refined detail of Polykleitos's models for casting executed in clay is revealed in a famous remark repeated in Plutarch's Moralia, that "the work is hardest when the clay is under the fingernail".[9]

The Canon of Polykleitos and "symmetria"

[edit]Polykleitos consciously created a new approach to sculpture, writing a treatise (an artistic canon (from Ancient Greek Κανών (Kanṓn) 'measuring rod, standard') and designing a male nude exemplifying his theory of the mathematical basis of ideal proportions. Though his theoretical treatise is lost to history,[10] he is quoted as saying, "Perfection ... comes about little by little (para mikron) through many numbers".[11] By this he meant that a statue should be composed of clearly definable parts, all related to one another through a system of ideal mathematical proportions and balance. Though his Canon was probably represented by his Doryphoros, the original bronze statue has not survived, but later marble copies exist.

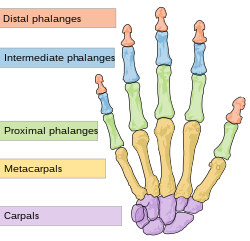

References to the Kanon by other ancient writers imply that its main principle was expressed by the Greek words symmetria, the Hippocratic principle of isonomia ("equilibrium"), and rhythmos. Galen wrote that Polykleitos's Kanon "got its name because it had a precise commensurability (symmetria) of all the parts to one another."[12] He also wrote that the Kanon defines beauty "in the proportions, not of the elements, but of the parts, that is to say, of finger to finger, and of all the fingers to the palm and the wrist, and of these to the forearm, and of the forearm to the upper arm, and of all the other parts to each other."[13]

The art historian Kenneth Clark observed that "[Polykleitos's] general aim was clarity, balance, and completeness; his sole medium of communication the naked body of an athlete, standing poised between movement and repose".[14]

Conjectured reconstruction

[edit]

Despite the many advances made by modern scholars towards a clearer comprehension of the theoretical basis of the Canon of Polykleitos, the results of these studies show an absence of any general agreement upon the practical application of that canon in works of art. An observation on the subject by Rhys Carpenter remains valid:[15] "Yet it must rank as one of the curiosities of our archaeological scholarship that no-one has thus far succeeded in extracting the recipe of the written canon from its visible embodiment, and compiling the commensurable numbers that we know it incorporates."

— Richard Tobin, The Canon of Polykleitos, 1975.[16]

In a 1975 paper, art historian Richard Tobin[b] suggested that earlier work to reconstruct the Canon had failed because previous researchers had made a flawed assumption of a foundation in linear ratios rather than areal proportion.[16] He conjectured that the Canon begins from the length of the outermost part (the "distal phalange") of the little finger. The length of the diagonal of a square of this side (mathematically, √2, about 1.4142) gives the length of the middle phalange. Repeating the process gives the length of the proximal phalange; doing so again gives the length of the metacarpal plus the carpal bones – the distance from knuckle to the head of the ulna. Next, a square of side equal to the length of the hand from little finger to wrist yields a diagonal of length equal to that of the forearm. This "diagonal of a square" process gives the relative ratios of many other key reference distances in the human male body.[18] The process would not require measurement of square roots: the artist could take a long cord and make knots separated from each other by a distance which equals the diagonal of the square drawn on the preceding length.[19] On the body proper, the process is repeated but the geometric progression is taken and retaken from the top of the head (rather than additively, as on the hand/arm): the head from crown to chin is the same size as the fore-arm; from crown to clavicle is as long as the upper arm; a diagonal on that square yields the distance from the crown to the line of the nipples.[20] Tobin validated his calculation by comparing his theoretical model with a Roman copy of Doryphoros in the National Archaeological Museum of Naples.[21]

Followers

[edit]Polykleitos and Phidias were among the first generation of Greek sculptors to attract schools of followers. Polykleitos's school lasted for at least three generations, but it seems to have been most active in the late 4th century and early 3rd century BCE. The Roman writers Pliny and Pausanias noted the names of about twenty sculptors in Polykleitos's school, defined by their adherence to his principles of balance and definition. Skopas and Lysippus are among the best-known successors of Polykleitos, along with other, more obscure statuaries, such as Athenodoros of Cleitor and Asopodorus.

Polykleitos's son, Polykleitos the Younger, worked in the 4th century BCE. Although the son was also a sculptor of athletes, his greatest fame was won as an architect. He designed the great theatre at Epidaurus.

Gallery

[edit]-

Doryphoros, Minneapolis Institute of Art

-

Bronze statue of an athlete from Ephesus cleaning his strigil; 1st century CE copy of a possible original by Polykleitos

-

Pan with flute, Roman copy of a possible original by Polykleitos

Notes

[edit]- ^ That a "school of Argos" existed during the fifth century is minimized as "marginal" by Jeffery M. Hurwit, "The Doryphoros: Looking Backward", in Warren G. Moon, ed. Polykleitos, the Doryphoros, and Tradition, 1995:3-18.

- ^ Richard Tobin holds a doctorate in Art History from Bryn Mawr College. Since April 2016, he is director of Harwood Museum of Art at the University of New Mexico.[17]

References

[edit]- ^ Blumberg, Naomi. "Polyclitus". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- ^ Andrew Stewart (1990). "Polykleitos of Argos". One Hundred Greek Sculptors: Their Careers and Extant Works. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- ^ Pliny the Elder Natural Histories 34.19.23

- ^ a b c d "Statue of Diadoumenos (youth tying a fillet around his head)". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia

- ^ "Statue of a wounded Amazon". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ a b c "Art: Doryphoros (Canon)". Art Through Time: A Global View. Annenberg Learner. Retrieved September 27, 2015.

- ^ "Greek vases 800-300 BC: key pieces". www.beazley.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 2021-05-20.

- ^ Plutarch, Quaest. conv. II 3, 2, 636B-C, quoted in Stewart.

- ^ "Art: Doryphoros (Canon)". Art Through Time: A Global View. Annenberg Learner. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

we are told quite unequivocally that he related every part to every other part and to the whole and used a mathematical formula in order to do so. What that formula was is a matter of conjecture.

- ^ Philo, Mechanicus, quoted in Stewart.

- ^ Galen, De Temperamentis.

- ^ De la Croix, Horst; Tansey, Richard G.; Kirkpatrick, Diane (1991). Gardner's Art Through the Ages (9th ed.). Thomson/Wadsworth. p. 163. ISBN 0-15-503769-2.

- ^ Clark 1956:63.

- ^ Rhys Carpenter (1960). Greek Sculpture : a critical review. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 100. cited in Tobin (1975), p. 307

- ^ a b Tobin (1975), p. 307.

- ^ "Tobin appointed director of UNM's Harwood Museum of Art" (Press release). 22 April 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ Tobin (1975), p. 309.

- ^ Tobin (1975), p. 310.

- ^ Tobin (1975), p. 313.

- ^ Tobin (1975), p. 315.

Sources

[edit]- Pausanias (1911) [143-176]. Description of Greece. Translated by W H S Jones. London: Heinman.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Polyclitus". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 22 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 22–23.

- Tobin, Richard (1975). "The Canon of Polykleitos". American Journal of Archaeology. 79 (4): 307–321. doi:10.2307/503064. JSTOR 503064. S2CID 191362470.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Polykleitos at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Polykleitos at Wikimedia Commons

Polykleitos

View on GrokipediaBiography

Name and Identity

Polykleitos, whose name in ancient Greek is rendered as Πολύκλειτος (Polúkleitos), derives etymologically from the adjective πολύκλειτος, meaning "far-famed" or "much-renowned," combining πολύς (polús, "much" or "many") and κλειτός (kleitós, "famed").[6][7] This name was Latinized in Roman sources as Polyclitus, Polycleitus, or Polycletus, reflecting variations in transliteration across classical texts.[7] Known primarily as "the Argive" due to his strong ties to the city of Argos, where he was likely born and which served as a major center of patronage for his bronzes, Polykleitos headed the Argive school of sculpture in the mid-5th century BCE.[8] Some later authors, writing in Latin and possibly drawing on Pliny the Elder's accounts, also dubbed him "the Sicyonian," likely alluding to a workshop or training in Sicyon, though modern scholars regard this as a potential error in ancient transmission rather than a definitive regional attribution.[9] To differentiate him from contemporaries and successors sharing similar names, Polykleitos is often specified as "the Elder," distinguishing him from his son, Polykleitos the Younger, a 4th-century BCE sculptor and architect best known for designing the Tholos at Epidaurus and the theater there.[8] No other prominent sculptors bore the exact name during his era, though the Argive school's output included related figures such as his pupils.[8] In ancient art criticism, Xenocrates of Athens, a 3rd-century BCE sculptor and historian whose treatise influenced Pliny, positioned Polykleitos between Phidias and Myron in the evolutionary canon of Greek sculpture, praising his refinement of proportions and contrapposto as a pivotal advancement in the depiction of the male athletic form.[10] This ranking underscored his role as a bridge between the monumental idealism of Phidias and the dynamic motion pioneered by Myron, establishing Polykleitos as a cornerstone of Classical statuary.[10]Early Life and Training

Polykleitos, known in ancient sources as Polykleitos the Argive to emphasize his regional ties, was active ca. 480/475–415 BCE.[11] He flourished during the mid-5th century BCE, producing works that established his reputation. Details of his early life remain sparse, drawn primarily from Roman-era accounts of Greek artists. According to Pliny the Elder, Polykleitos trained under the sculptor Ageladas of Argos, a specialist in bronze casting who also instructed the prominent figures Phidias and Myron. This mentorship would have immersed him in the technical foundations of bronze sculpture, a hallmark of Argive artistry during this period.[12] In the 5th century BCE, Argos emerged as a key cultural center in the Peloponnese, fostering artistic innovation through patronage from local elites and major sanctuaries that commissioned large-scale works. This environment rivaled the cultural prominence of Athens, providing a fertile ground for sculptors amid the broader Peloponnesian artistic scene, where regional workshops competed and exchanged ideas with Athenian contemporaries like Phidias.[13][14]Artistic Principles

Style and Technique

Polykleitos is renowned for his use and refinement of the contrapposto pose in his sculptures, a technique involving a subtle shift of weight onto one leg while the other is relaxed, which creates an elegant S-curve in the body's silhouette to achieve greater naturalism and a sense of implied dynamism.[2] This innovation marked a departure from the rigid, frontal stances of earlier Greek sculpture, allowing figures to appear more lifelike and poised in subtle motion.[15] Complementing contrapposto, Polykleitos employed chiastic composition, where opposing limbs cross in a balanced arrangement—such as one arm flexed and the opposite leg extended—to convey both stability and the potential for movement, enhancing the overall harmony of the form.[15] He showed a strong preference for bronze as his primary material, which permitted the capture of intricate details and a sense of vitality in his works, often beginning with highly refined clay models to meticulously render anatomical features.[16] Ancient accounts attribute to Polykleitos the observation that the sculptor's task becomes most challenging at the stage where the clay model reaches the precision of the fingernails, underscoring his commitment to exhaustive detail in modeling before casting.[17] This approach enabled the depiction of subtle musculature, with carefully modulated tensions and relaxations that suggested underlying strength without exaggeration. Polykleitos' sculptures typically featured idealized male nude figures representing athletic youths, evolving the archaic kouros tradition toward a more anatomically convincing and proportionate ideal.[18] These figures exhibit serene expressions and understated muscular development, emphasizing composure and inner balance over dramatic intensity, with symmetria serving as the guiding principle for their proportional coherence.[15]The Canon and Symmetria

Polykleitos composed the Canon, a treatise around 450 BCE, which served as a manual outlining mathematical ratios to achieve ideal human proportions in sculpture. This work prescribed specific relationships between body parts, such as the head measuring approximately one-eighth of the total height and proportional relationships between fingers, palm, wrist, and forearm. These ratios aimed to create a harmonious and idealized figure, reflecting Polykleitos' belief in a systematic approach to artistic creation grounded in numerical precision.[19][20] Central to the Canon was the concept of symmetria, defined as the balanced commensurability of parts relative to each other and to the whole, distinct from mere visual symmetry. Rather than rigid equality, symmetria involved subtle adjustments to integrate anatomical realism with ideal form, such as subtracting from exaggerated elements to avoid excess and ensure proportional unity. This process emphasized that true beauty emerges from the dynamic interplay of components, where deviations from strict geometry enhance overall coherence.[19] The philosophical foundations of the Canon drew from Pythagorean mathematics, promoting harmony between form and function through numerical patterns observed in nature. Polykleitos viewed sculpture as an embodiment of cosmic order, where proportional ratios mirrored the universe's underlying structure, blending aesthetic ideals with ethical and functional balance in the human figure.[20] Ancient writers like Galen and Vitruvius preserved fragments of the Canon's principles, highlighting its emphasis on a deliberate creative process. Galen, in De placitis Hippocratis et Platonis, described beauty as arising from the symmetria of parts—like finger to finger, fingers to palm, and forearm to arm—rather than elemental composition alone, underscoring Polykleitos' focus on relational proportions. Vitruvius, in De Architectura, echoed this by detailing body measurements derived from sculptural canons, noting how beauty is refined through iterative removal of excess to align parts in perfect measure.[19][17]Reconstruction of the Canon

The original treatise known as the Canon by Polykleitos has not survived, leaving scholars to rely on fragmentary ancient testimonia, such as quotes from Galen and summaries possibly from Plutarch, alongside measurements derived from Roman marble copies of his bronze sculptures.[17] Galen, for instance, described how Polykleitos supported his proportional principles with a statue embodying the Canon, emphasizing that beauty arises from the precise commensurability of parts like finger to finger and all fingers to the palm and wrist.[21] These ancient references, combined with the dimensions of copies like the Naples Doryphoros, form the primary basis for modern reconstructions, though Roman adaptations introduce uncertainties in scale and fidelity to the Greek originals.[17] Scholarly efforts to reconstruct the Canon have centered on interpreting its proportional system, with a key debate contrasting linear ratios—popularized in 19th-century analyses—with areal proportions proposed by Richard Tobin in 1975. Earlier 19th-century diagrams, such as those by scholars like August Kalkmann, illustrated linear schemes where the head height divided the body into ratios like 1:7 or 1:8, and the finger served as a basic module equating to specific segments like the palm or forearm, often visualized through grid-based overlays on statue photographs.[17] Tobin, however, argued for a geometric framework rooted in Greek philosophy, using the distal phalange of the little finger as the foundational module and deriving body proportions through continuous geometric progressions and areal divisions, such as structuring the torso and limbs within cubic volumes to achieve symmetria.[21] This approach aligns the Canon more closely with Pythagorean principles of harmony, emphasizing surface areas over strict linear measurements for a more dynamic representation of the human form.[21] Ongoing debates highlight the challenges in pinpointing exact numerical values and applications, particularly given the Canon's apparent focus on male figures. Measurements from the Naples Doryphoros yield varying head-to-body ratios—approaching 1:7 in some analyses but closer to 1:8 in others—due to inconsistencies in copy restoration and measurement techniques, as critiqued by Andrew Stewart.[17] Scholars like Hans von Steuben and Tobin have proposed multivariate analyses of multiple copies to refine these ratios, yet no consensus exists on whether the Canon extended uniformly to female forms, with evidence from statues like the Ephesus Amazon suggesting adaptations for gender-specific proportions that deviate from the male ideal.[17] These disputes underscore the Canon's emphasis on symmetria as an adjustable principle rather than a rigid formula, influencing continued visualizations through updated diagrams that incorporate both linear and areal models.[21]Major Works

Doryphoros

The Doryphoros, or Spear-Bearer, is Polykleitos' most renowned sculpture, an over-life-size bronze statue dating to approximately 440 BCE that depicts a nude male youth poised as if carrying a spear over his left shoulder. The original Greek bronze is lost, but the work survives through numerous Roman-era marble copies, with the finest and most complete example discovered in Pompeii and now housed in the National Archaeological Museum in Naples, measuring about 211 cm in height. These copies preserve the figure's athletic idealism, showcasing Polykleitos' mastery of the human form in a moment of poised stillness.[22][11] The statue's pose exemplifies the revolutionary contrapposto technique, with the figure's weight resting primarily on his right leg, causing the left hip to lift and the right to drop slightly, while the left leg advances forward in a relaxed stance. This creates an elegant S-shaped contrapposto curve through the torso, with the right arm extended downward along the engaged leg and the left arm bent upward to support the missing spear, the hand originally positioned near the shoulder. The head turns subtly to the right, enhancing the chiastic balance where tensed and relaxed elements—such as the supporting right side opposing the freer left—interlock in harmonious opposition, conveying both strength and natural ease.[11][23] Polykleitos' proportional system is vividly realized in the Doryphoros, where the head measures one-seventh of the total body height, the forearm one-quarter of the body length, and other limbs and torso segments follow precise numerical ratios derived from his theoretical treatise, the Canon, to achieve symmetria or commensurate proportion. These ratios ensure a balanced yet asymmetrical composition, with the upper and lower body subtly counterpoised to reflect organic vitality rather than rigid symmetry.[24] Created in Argos, Polykleitos' native city, the Doryphoros was likely commissioned for dedication in a local temple, possibly the Heraion, and served as a symbolic embodiment of the classical Greek ideal of the warrior-athlete, blending martial readiness with harmonious physical perfection. As the practical demonstration of his Canon, the statue influenced generations of sculptors by prioritizing measured proportions to evoke an aura of divine order in the human body.[25][26]Diadumenos

The Diadumenos, or "youth tying a fillet," is a bronze statue created by Polykleitos around 430 BCE, depicting a nude young athlete binding a victor's ribbon around his head following success in a competition.[1] The original work is lost, but it survives through numerous Roman marble copies, including a well-preserved example from Vaison-la-Romaine in France, now in the British Museum, which captures the figure's poised elegance.[27] This statue exemplifies Polykleitos' mastery in rendering the human form in a moment of quiet triumph, with the youth's body relaxed yet dynamically engaged in the simple act of self-adornment. The pose features a subtle contrapposto, where the thorax and pelvis tilt in opposite directions to create rhythmic contrasts and a sense of torsion, while the raised arms heighten the implication of gentle motion.[1] The feet are positioned as if transitioning between standing and walking, enhancing the overall fluidity without overt drama. Proportional features align closely with those in Polykleitos' Doryphoros, employing harmonious ratios for balance, but the musculature here is rendered softer and more supple to convey youthful grace rather than rigid strength.[1] This adjustment highlights a deliberate stylistic variation, as noted by ancient sources describing the Diadumenos as "soft-looking" compared to its more martial counterparts.[28] Likely intended as a votive offering, the statue would have been placed in a sanctuary such as Olympia or Delphi, celebrating athletic achievement through an everyday ritual of binding the fillet.[1] This focus on post-victory adornment shifts away from combative themes, emphasizing instead the serene, ritualistic aspect of Greek athletic culture and Polykleitos' ability to infuse symmetria into asymmetrical actions for visual harmony.[1]Other Notable Works

Among the additional sculptures attributed to Polykleitos are several bronze works that demonstrate his versatility in applying canonical proportions to diverse subjects, from youthful athletes to divine figures.[29] The Discophoros, or discus-bearer, depicts a youthful male figure in a contrapposto pose akin to the Doryphoros, but with one arm dynamically extended to hold a discus, introducing greater movement while maintaining balanced proportions.[30] Roman marble copies, such as one in the Museo del Prado, preserve the original's emphasis on anatomical harmony and poised energy.[30] For the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, Polykleitos contributed an Amazon statue, identified in ancient accounts as a wounded warrior—likely seated or standing with an arrow in her side—merging his ideal male-derived forms with emotional pathos to convey vulnerability and resilience. This work, part of a renowned competition among sculptors including Pheidias and Kresilas, was praised for its superior execution among the temple's bronze Amazons.[4] The Lansdowne type, a Roman copy, is conventionally linked to Polykleitos' design.[4] Polykleitos' most ambitious non-bronze project was the colossal chryselephantine statue of Hera for the Heraion at Argos, a seated gold-and-ivory figure enthroned with a pomegranate in one hand and a scepter in the other, radiating divine majesty through its monumental scale and luxurious materials.[29] Commissioned after a temple fire around 423 BCE, it stood over 5 meters tall and was celebrated in antiquity as a pinnacle of sacred art, comparable to Pheidias' Zeus at Olympia.[8] Other attributions include the Hermes Propylaios from Lysimachea, a single-figure bronze likely portraying the god as a gatekeeper in a relaxed yet vigilant stance, and the Astragalizontes, a lively group of two nude boys engaged in playing knucklebones, capturing playful interaction through fluid poses and expressive gestures. Pliny the Elder particularly lauded the Astragalizontes as the most perfect artwork known. None of these originals survive, as they were crafted in perishable bronze or composite materials; knowledge of them derives primarily from Pliny's descriptions in Natural History (Book 34) and scattered Roman marble copies that echo Polykleitos' stylistic hallmarks.[31]Legacy

Followers and School

The school of Polykleitos, centered in Argos, remained active for three generations after his primary period of activity around 420 BCE, perpetuating his emphasis on proportional harmony in sculpture.[32] Key figures among his immediate successors included his apprentices Aristides and Patroklos, who specialized in bronze works depicting athletes and warriors.[33] Aristides, active circa 420 BCE, was noted for producing chariot groups that echoed Polykleitos' dynamic poses and balanced forms.[33] Patroklos, working around 400 BCE, contributed to collaborative memorials such as the Aigospotamoi monument (405 BCE) and maintained the workshop's tradition of detailed bronze casting for human figures.[32] Patroklos' family extended this lineage, with his son Naukydes producing ivory-and-gold statues like Hebe and emphasizing proportional accuracy in his designs around 400 BCE.[32] Naukydes served as teacher to Polykleitos the Younger, who likely was the son or close successor of the elder Polykleitos and active in the late 5th to early 4th century BCE.[32] While continuing sculptural work, such as marble statues of Zeus and athletes, Polykleitos the Younger is best known for his architectural contributions, including the design of the Theatre at Epidaurus circa 350 BCE, renowned for its symmetry and acoustics.[34] Workshop practices in the Polykleitan tradition involved collaborative production of bronze sculptures, where apprentices assisted in casting and finishing to achieve the precise symmetria outlined in the Canon, with its principles often transmitted orally through hands-on training rather than solely through the written treatise.[32] This Argive-based approach, focused on robust, idealized male figures, distinguished the school from the Athenian circle of Phidias, which prioritized large-scale chryselephantine statues for divine cult worship in temples.[33]Influence on Later Art

Polykleitos' principles of proportion and symmetria profoundly shaped Hellenistic sculpture, where artists like Lysippus adapted his canon to create taller, slimmer figures with smaller heads relative to the body, emphasizing a more dynamic and elongated silhouette compared to the balanced, robust forms of the Classical period.[35] Lysippus, in particular, is noted for revising Polykleitos' proportional system to produce a greater sense of depth and realism, influencing the transition to Hellenistic styles that prioritized individuality and movement.[36] Similarly, Skopas drew from Polykleitos' foundational techniques but infused them with heightened emotional expressiveness, resulting in figures that conveyed intense pathos through facial features and dynamic poses, as seen in his contributions to the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus.[37] In the Roman era, Polykleitos' works gained widespread dissemination through marble copies displayed in elite villas, public forums, and baths, serving as exemplars of Greek artistic excellence and symbols of cultural sophistication.[2] The Doryphoros, for instance, was replicated extensively, with notable examples found in Pompeii and other sites, reflecting Roman admiration for its contrapposto stance and idealized anatomy.[16] The architect Vitruvius praised Polykleitos' canon in De Architectura, integrating its bodily proportions—such as the foot equaling one-sixth of the height—into architectural design principles for temples and human-scale structures, thereby extending sculptural ideals to built environments.[38][20] During the Renaissance, Polykleitos' legacy revived as artists and theorists sought classical models for human representation. Michelangelo's David (1501–1504) echoes the Doryphoros in its contrapposto pose and emphasis on anatomical harmony, though with exaggerated proportions to convey psychological tension and heroic scale.[39][40] Leon Battista Alberti, in his treatise De Pictura (1435), referenced ancient proportional systems like Polykleitos' to advocate for mathematical harmony in depicting the nude body, influencing Renaissance ideals of beauty and composition.[41] In modern Western sculpture, Polykleitos' canon remains a cornerstone of anatomical ideals, informing the depiction of the male form in works from neoclassical to contemporary art, where balanced proportions symbolize physical perfection and restraint.[42] However, recent critiques highlight its male-centric focus, sparking debates on gender inclusivity by questioning the exclusion of diverse body types and prompting adaptations that incorporate female or non-binary forms to challenge traditional canons.[43] Post-2000 scholarship has advanced digital reconstructions of Polykleitos' bronzes, such as 3D models of the Doryphoros using scanned Roman copies to hypothesize original surfaces and poses, enhancing understanding of lost originals.[44][45] Additionally, studies since 2000 explore parallels in non-Western traditions, noting conceptual similarities between Polykleitos' symmetria and proportional systems in Greco-Scythian art or ancient Indian iconometry, though direct influences remain debated.[46]References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Polyclitus