Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

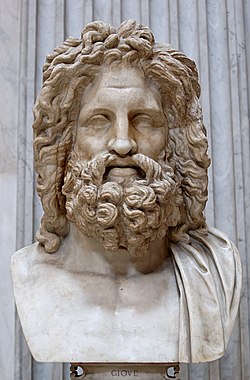

| Zeus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Abode | Mount Olympus |

| Symbol | Thunderbolt, eagle |

| Genealogy | |

| Parents | Cronus and Rhea |

| Siblings | Hestia, Hades, Hera, Poseidon and Demeter |

| Spouse | |

| Children | see list |

| Equivalents | |

| Roman | Jupiter |

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Greek religion |

|---|

|

Zeus (/zjuːs/, Ancient Greek: Ζεύς)[a] is the chief deity of the Greek pantheon. He is a sky and thunder god in ancient Greek religion and mythology, who rules as king of the gods on Mount Olympus.

Zeus is the child of Cronus and Rhea, the youngest of his siblings to be born, though sometimes reckoned the eldest as the others required disgorging from Cronus's stomach. In most traditions, he is married to Hera, by whom he is usually said to have fathered Ares, Eileithyia, Hebe, and Hephaestus.[2][3] At the oracle of Dodona, his consort was said to be Dione,[4] by whom the Iliad states that he fathered Aphrodite.[7] According to the Theogony, Zeus's first wife was Metis, by whom he had Athena.[8] Zeus was also infamous for his erotic escapades. These resulted in many divine and heroic offspring, including Apollo, Artemis, Hermes, Persephone, Dionysus, Perseus, Heracles, Helen of Troy, Minos, and the Muses.[2]

He was respected as a sky father who was chief of the gods[9] and assigned roles to the others:[10] "Even the gods who are not his natural children address him as Father, and all the gods rise in his presence."[11][12] He was equated with many foreign weather gods, permitting Pausanias to observe "That Zeus is king in heaven is a saying common to all men".[13] Among his symbols are the thunderbolt and the eagle.[14] In addition to his Indo-European inheritance, the classical "cloud-gatherer" (Greek: Νεφεληγερέτα, Nephelēgereta)[15] also derives certain iconographic traits from the cultures of the ancient Near East, such as the scepter.

Name

[edit]The god's name in the nominative is Ζεύς (Zeús). It is inflected as follows: vocative: Ζεῦ (Zeû); accusative: Δία (Día); genitive: Διός (Diós); dative: Διί (Dií). Diogenes Laërtius quotes Pherecydes of Syros as spelling the name Ζάς.[16] The earliest attested forms of the name are the Mycenaean Greek 𐀇𐀸, di-we (dative) and 𐀇𐀺, di-wo (genitive), written in the Linear B syllabic script.[17]

Zeus is the Greek continuation of *Dyēus the name of the Proto-Indo-European god of the daytime sky, also called *Dyeus ph2tēr ("Sky Father").[18][19] The god is known under this name in the Rigveda (Vedic Sanskrit Dyaus/Dyaus Pita), Latin (compare Jupiter, from Iuppiter, deriving from the Proto-Indo-European vocative *dyeu-ph2tēr),[20] deriving from the root *dyeu- ("to shine", and in its many derivatives, "sky, heaven, god").[18] Albanian Zoj-z and Messapic Zis are clear equivalents and cognates of Zeus. In the Greek, Albanian, and Messapic forms the original cluster *di̯ underwent affrication to *dz.[21][22] Zeus is the only deity in the Olympic pantheon whose name has such a transparent Indo-European etymology.[23]

Plato, in his Cratylus, gives a folk etymology of Zeus meaning "cause of life always to all things", because of puns between alternate titles of Zeus (Zen and Dia) with the Greek words for life and "because of".[24] This etymology, along with Plato's entire method of deriving etymologies, is not supported by modern scholarship.[25][26]

Diodorus Siculus wrote that Zeus was also called Zen, because the humans believed that he was the cause of life (zen).[27] While Lactantius wrote that he was called Zeus and Zen, not because he is the giver of life, but because he was the first who lived of the children of Cronus.[28]

Zeus was called by numerous alternative names or surnames, known as epithets. Some epithets are the surviving names of local gods who were consolidated into the myth of Zeus.[29]

Mythology

[edit]Birth

[edit]In Hesiod's Theogony (c. 730 – 700 BC), Cronus, after castrating his father Uranus,[30] becomes the supreme ruler of the cosmos, and weds his sister Rhea, by whom he begets three daughters and three sons: Hestia, Demeter, Hera, Hades, Poseidon, and lastly, "wise" Zeus, the youngest of the six.[31] He swallows each child as soon as they are born, having received a prophecy from his parents, Gaia and Uranus, that one of his own children is destined to one day overthrow him as he overthrew his father.[32] This causes Rhea "unceasing grief",[33] and upon becoming pregnant with her sixth child, Zeus, she approaches her parents, Gaia and Uranus, seeking a plan to save her child and bring retribution to Cronus.[34] Following her parents' instructions, she travels to Lyctus in Crete, where she gives birth to Zeus,[35] handing the newborn child over to Gaia for her to raise, and Gaia takes him to a cave on Mount Aegaeon (Aegeum).[36] Rhea then gives to Cronus, in the place of a child, a stone wrapped in swaddling clothes, which he promptly swallows, unaware that it is not his son.[37]

While Hesiod gives Lyctus as Zeus's birthplace, he is the only source to do so,[38] and other authors give different locations. The poet Eumelos of Corinth (8th century BC), according to John the Lydian, considered Zeus to have been born in Lydia,[39] while the Alexandrian poet Callimachus (c. 310 – c. 240 BC), in his Hymn to Zeus, says that he was born in Arcadia.[40] Diodorus Siculus (fl. 1st century BC) seems at one point to give Mount Ida as his birthplace, but later states he is born in Dicte,[41] and the mythographer Apollodorus (first or second century AD) similarly says he was born in a cave in Dicte.[42] In the second century AD, Pausanias wrote that it would be impossible to count all the people claiming that Zeus was born or brought up among them.[43]

| Children of Cronus and Rhea[44] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Infancy

[edit]

While the Theogony says nothing of Zeus's upbringing other than that he grew up swiftly,[45] other sources provide more detailed accounts. According to Apollodorus, Rhea, after giving birth to Zeus in a cave in Dicte, gives him to the nymphs Adrasteia and Ida, daughters of Melisseus, to nurse.[46] They feed him on the milk of the she-goat Amalthea,[47] while the Kouretes guard the cave and beat their spears on their shields so that Cronus cannot hear the infant's crying.[48] Diodorus Siculus provides a similar account, saying that, after giving birth, Rhea travels to Mount Ida and gives the newborn Zeus to the Kouretes,[49] who then takes him to some nymphs (not named), who raised him on a mixture of honey and milk from the goat Amalthea.[50] He also refers to the Kouretes "rais[ing] a great alarum", and in doing so deceiving Cronus,[51] and relates that when the Kouretes were carrying the newborn Zeus that the umbilical cord fell away at the river Triton.[52]

Hyginus, the author of the Fabulae, relates a version in which Cronus casts Poseidon into the sea and Hades to the Underworld instead of swallowing them. When Zeus is born, Hera (also not swallowed), asks Rhea to give her the young Zeus, and Rhea gives Cronus a stone to swallow.[53] Hera gives him to Amalthea, who hangs his cradle from a tree, where he is not in heaven, on earth or in the sea, meaning that when Cronus later goes looking for Zeus, he is unable to find him.[54] Hyginus also says that Ida, Althaea, and Adrasteia, usually considered the children of Oceanus, are sometimes called the daughters of Melisseus and the nurses of Zeus.[55]

According to a fragment of Epimenides, the nymphs Helice and Cynosura are the young Zeus's nurses. Cronus travels to Crete to look for Zeus, who, to conceal his presence, transforms himself into a snake and his two nurses into bears.[56] According to Musaeus, after Zeus is born, Rhea gives him to Themis. Themis in turn gives him to Amalthea, who owns a she-goat, which nurses the young Zeus.[57]

Antoninus Liberalis, in his Metamorphoses, says that Rhea gives birth to Zeus in a sacred cave in Crete, full of sacred bees, which become the nurses of the infant. While the cave is considered forbidden ground for both mortals and gods, a group of thieves seek to steal honey from it. Upon laying eyes on the swaddling clothes of Zeus, their bronze armour "split[s] away from their bodies", and Zeus would have killed them had it not been for the intervention of the Moirai and Themis; he instead transforms them into various species of birds.[58]

Ascension to power

[edit]

According to the Theogony, after Zeus reaches manhood, Cronus is made to disgorge the five children and the stone "by the stratagems of Gaia, but also by the skills and strength of Zeus", presumably in reverse order, vomiting out the stone first, then each of the five children in the opposite order to swallowing.[59] Zeus then sets up the stone at Delphi, so that it may act as "a sign thenceforth and a marvel to mortal men".[60] Zeus next frees the Cyclopes, who, in return, and out of gratitude, give him his thunderbolt, which had previously been hidden by Gaia.[61] Then begins the Titanomachy, the war between the Olympians, led by Zeus, and the Titans, led by Cronus, for control of the universe, with Zeus and the Olympians fighting from Mount Olympus, and the Titans fighting from Mount Othrys.[62] The battle lasts for ten years with no clear victor emerging, until, upon Gaia's advice, Zeus releases the Hundred-Handers, who (similarly to the Cyclopes) were imprisoned beneath the Earth's surface.[63] He gives them nectar and ambrosia and revives their spirits,[64] and they agree to aid him in the war.[65] Zeus then launches his final attack on the Titans, hurling bolts of lightning upon them while the Hundred-Handers attack with barrages of rocks, and the Titans are finally defeated, with Zeus banishing them to Tartarus and assigning the Hundred-Handers the task of acting as their warders.[66]

Apollodorus provides a similar account, saying that, when Zeus reaches adulthood, he enlists the help of the Oceanid Metis, who gives Cronus an emetic, forcing to him to disgorge the stone and Zeus's five siblings.[67] Zeus then fights a similar ten-year war against the Titans, until, upon the prophesying of Gaia, he releases the Cyclopes and Hundred-Handers from Tartarus, first slaying their warder, Campe.[68] The Cyclopes give him his thunderbolt, Poseidon his trident and Hades his helmet of invisibility, and the Titans are defeated and the Hundred-Handers made their guards.[68]

According to the Iliad, after the battle with the Titans, Zeus shares the world with his brothers, Poseidon and Hades, by drawing lots: Zeus receives the sky, Poseidon the sea, and Hades the underworld, with the earth and Olympus remaining common ground.[69]

Challenges to power

[edit]

Upon assuming his place as king of the cosmos, Zeus's rule is quickly challenged. The first of these challenges to his power comes from the Giants, who fight the Olympian gods in a battle known as the Gigantomachy. According to Hesiod, the Giants are the offspring of Gaia, born from the drops of blood that fell on the ground when Cronus castrated his father Uranus;[70] there is, however, no mention of a battle between the gods and the Giants in the Theogony.[71] It is Apollodorus who provides the most complete account of the Gigantomachy. He says that Gaia, out of anger at how Zeus had imprisoned her children, the Titans, bore the Giants to Uranus.[72] There comes to the gods a prophecy that the Giants cannot be defeated by the gods on their own, but can be defeated only with the help of a mortal; Gaia, upon hearing of this, seeks a special pharmakon (herb) that will prevent the Giants from being killed. Zeus, however, orders Eos (Dawn), Selene (Moon) and Helios (Sun) to stop shining, and harvests all of the herb himself, before having Athena summon Heracles.[73] In the conflict, Porphyrion, one of the most powerful of the Giants, launches an attack upon Heracles and Hera; Zeus, however, causes Porphyrion to become lustful for Hera, and when he is just about to violate her, Zeus strikes him with his thunderbolt, before Heracles deals the fatal blow with an arrow.[74]

In the Theogony, after Zeus defeats the Titans and banishes them to Tartarus, his rule is challenged by the monster Typhon, a giant serpentine creature who battles Zeus for control of the cosmos. According to Hesiod, Typhon is the offspring of Gaia and Tartarus,[75] described as having a hundred snaky fire-breathing heads.[76] Hesiod says he "would have come to reign over mortals and immortals" had it not been for Zeus noticing the monster and dispatching with him quickly:[77] the two of them meet in a cataclysmic battle, before Zeus defeats him easily with his thunderbolt, and the creature is hurled down to Tartarus.[78] Epimenides presents a different version, in which Typhon makes his way into Zeus's palace while he is sleeping, only for Zeus to wake and kill the monster with a thunderbolt.[79] Aeschylus and Pindar give somewhat similar accounts to Hesiod, in that Zeus overcomes Typhon with relative ease, defeating him with his thunderbolt.[80] Apollodorus, in contrast, provides a more complex narrative.[81] Typhon is, similarly to in Hesiod, the child of Gaia and Tartarus, produced out of anger at Zeus's defeat of the Giants.[82] The monster attacks heaven, and all of the gods, out of fear, transform into animals and flee to Egypt, except for Zeus, who attacks the monster with his thunderbolt and sickle.[83] Typhon is wounded and retreats to Mount Kasios in Syria, where Zeus grapples with him, giving the monster a chance to wrap him in his coils, and rip out the sinews from his hands and feet.[84] Disabled, Zeus is taken by Typhon to the Corycian Cave in Cilicia, where he is guarded by the "she-dragon" Delphyne.[85] Hermes and Aegipan, however, steal back Zeus's sinews, and refit them, reviving him and allowing him to return to the battle, pursuing Typhon, who flees to Mount Nysa; there, Typhon is given "ephemeral fruits" by the Moirai, which reduce his strength.[86] The monster then flees to Thrace, where he hurls mountains at Zeus, which are sent back at him by the god's thunderbolts, before, while fleeing to Sicily, Zeus launches Mount Etna upon him, finally ending him.[87] Nonnus, who gives the longest and most detailed account, presents a narrative similar to Apollodorus, with differences such as that it is instead Cadmus and Pan who recovers Zeus's sinews, by luring Typhon with music and then tricking him.[88]

In the Iliad, Homer tells of another attempted overthrow, in which Hera, Poseidon, and Athena conspire to overpower Zeus and tie him in bonds. It is only because of the Nereid Thetis, who summons Briareus, one of the Hecatoncheires, to Olympus, that the other Olympians abandon their plans (out of fear for Briareus).[89]

Partners before Hera

[edit]

According to Hesiod, Zeus takes Metis, one of the Oceanid daughters of Oceanus and Tethys, as his first wife. However, when she is about to give birth to a daughter, Athena, he swallows her whole upon the advice of Gaia and Uranus, as it had been foretold that after bearing a daughter, she would give birth to a son, who would overthrow him as king of gods and mortals; it is from this position that Metis gives counsel to Zeus. In time, Athena is born, emerging from Zeus's head, but the foretold son never comes forth.[90] Apollodorus presents a similar version, stating that Metis took many forms in attempting to avoid Zeus's embraces, and that it was Gaia alone who warned Zeus of the son who would overthrow him.[91] According to a fragment likely from the Hesiodic corpus,[92] quoted by Chrysippus, it is out of anger at Hera for producing Hephaestus on her own that Zeus has intercourse with Metis, and then swallows her, thereby giving rise to Athena from himself.[93] A scholiast on the Iliad, in contrast, states that when Zeus swallows her, Metis is pregnant with Athena not by Zeus himself, but by the Cyclops Brontes.[94] The motif of Zeus swallowing Metis can be seen as a continuation of the succession myth: it is prophesied that a son of Zeus will overthrow him, just as he overthrew his father, but whereas Cronos met his end because he did not swallow the real Zeus, Zeus holds onto his power because he successfully swallows the threat, in the form of the potential mother, and so the "cycle of displacement" is brought to an end.[95] In addition, the myth can be seen as an allegory for Zeus gaining the wisdom of Metis for himself by swallowing her.[96]

In Hesiod's account, Zeus's second wife is Themis, one of the Titan daughters of Uranus and Gaia, with whom he has the Horae, listed as Eunomia, Dike and Eirene, and the three Moirai: Clotho, Lachesis and Atropos.[97] A fragment from Pindar calls Themis Zeus's first wife, and states that she is brought by the Moirai (in this version not her daughters) up to Olympus, where she becomes the bride of Zeus and bears him the Horae.[98] According to Hesiod, Zeus lies next with the Oceanid Eurynome, by whom he becomes the father of the three Charites: Aglaea, Euphrosyne and Thalia.[99] Zeus then partners with his sister Demeter, producing Persephone.[100] Zeus's next union is with the Titan Mnemosyne; as described at the beginning of the Theogony, Zeus lies with Mnemosyne in Piera each night for nine nights, producing the nine Muses.[101] His next partner is the Titan Leto, by whom he fathers the twins Apollo and Artemis, who, according to the Homeric Hymn to Apollo, are born on the island of Delos.[102] In Hesiod's account, only then does Zeus take his sister Hera as his wife.[103]

| Children of Zeus and his partners before Hera[104] |

|---|

Marriage to Hera

[edit]

While Hera is Zeus's last wife in Hesiod's version, in other accounts she is his first and only wife.[108] In the Theogony, the couple has three children, Ares, Hebe, and Eileithyia.[109] While Hesiod states that Hera produces Hephaestus on her own after Athena is born from Zeus's head,[110] other versions, including Homer, have Hephaestus as a child of Zeus and Hera as well.[111]

Various authors give descriptions of a youthful affair between Zeus and Hera. In the Iliad, the pair are described as having first lay with each other before Cronus is sent to Tartarus, without the knowledge of their parents.[112] A scholiast on the Iliad states that, after Cronus is banished to Tartarus, Oceanus and Tethys give Hera to Zeus in marriage, and only shortly after the two are wed, Hera gives birth to Hephaestus, having lay secretly with Zeus on the island of Samos beforehand; to conceal this act, she claimed that she had produced Hephaestus on her own.[113] According to another scholiast on the Iliad, Callimachus, in his Aetia, says that Zeus lay with Hera for three hundred years on the island of Samos.[114]

According to a scholion on Theocritus's Idylls, Zeus, one day seeing Hera walking apart from the other gods, becomes intent on having intercourse with her, and transforms himself into a cuckoo bird, landing on Mount Thornax. He creates a terrible storm, and when Hera arrives at the mountain and sees the bird, which sits on her lap, she takes pity on it, laying her cloak over it. Zeus then transforms back and takes hold of her; when she refuses to have intercourse with him because of their mother, he promises that she will become his wife.[115] Pausanias similarly refers to Zeus transforming himself into a cuckoo to woo Hera, and identifies the location as Mount Thornax.[116]

According to a version from Plutarch, as recorded by Eusebius in his Praeparatio evangelica, Hera is raised by a nymph named Macris[117] on the island of Euboea when Zeus kidnaps her, taking her to Mount Cithaeron, where they find a shady hollow, which serves as a "natural bridal chamber". When Macris comes to look for Hera, Cithaeron, the tutelary deity of the mountain, stops her, saying that Zeus is sleeping there with Leto.[118] Photius, in his Bibliotheca, tells us that in Ptolemy Hephaestion's New History, Hera refuses to lay with Zeus, and hides in a cave to avoid him, before an earthborn man named Achilles convinces her to marry Zeus, leading to the pair first sleeping with each other.[119] According to Stephanus of Byzantium, Zeus and Hera first lay together at the city of Hermione, having come there from Crete.[120] Callimachus, in a fragment from his Aetia, also apparently makes reference to the couple's union occurring at Naxos.[121]

Though no complete account of Zeus and Hera's wedding exists, various authors make reference to it. According to a scholiast on Apollonius of Rhodes's Argonautica, Pherecydes states that when Zeus and Hera are being married, Gaia brings a tree which produces golden apples as a wedding gift.[122] Eratosthenes and Hyginus attribute a similar story to Pherecydes, in which Hera is amazed by the gift, and asks for the apples to be planted in the "garden of the gods", nearby to Mount Atlas.[123] Apollodorus specifies them as the golden apples of the Hesperides, and says that Gaia gives them to Zeus after the marriage.[124] According to Diodorus Siculus, the location of the marriage is in the land of the Knossians, nearby to the river Theren,[125] while Lactantius attributes to Varro the statement that the couple are married on the island of Samos.[126]

There exist several stories in which Zeus, receiving advice, is able to reconcile with an angered Hera. According to Pausanias, Hera, angry with her husband, retreats to the island of Euboea, where she was raised, and Zeus, unable to resolve the situation, seeks the advice of Cithaeron, ruler of Plataea, supposedly the most intelligent man on earth. Cithaeron instructs him to fashion a wooden statue and dress it as a bride, and then pretend that he is marrying one "Plataea", a daughter of Asopus. When Hera hears of this, she immediately rushes there, only to discover the ruse upon ripping away the bridal clothing; she is so relieved that the couple are reconciled.[127] According to a version from Plutarch, as recorded by Eusebius in his Praeparatio evangelica, when Hera is angry with her husband, she retreats instead to Cithaeron, and Zeus goes to the earth-born man Alalcomeneus, who suggests he pretend to marry someone else. With the help of Alalcomeneus, Zeus creates a wooden statue from an oak tree, dresses it as a bride, and names it Daidale. When preparations are being made for the wedding, Hera rushes down from Cithaeron, followed by the women of Plataia, and upon discovering the trick, the couple are reconciled, with the matter ending in joy and laughter among all involved.[128]

| Children of Zeus and Hera[129] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Affairs

[edit]

After his marriage to Hera, different authors describe Zeus's numerous affairs with various mortal women.[131] In many of these affairs, Zeus transforms himself into an animal, someone else, or some other form. According to a scholion on the Iliad (citing Hesiod and Bacchylides), when Europa is picking flowers with her female companions in a meadow in Phoenicia, Zeus transforms himself into a bull, lures her from the others, and then carries her across the sea to the island of Crete, where he resumes his usual form to sleep with her.[132] In Euripides's Helen, Zeus takes the form of a swan, and after being chased by an eagle, finds shelter in the lap of Leda, subsequently seducing her,[133] while in Euripides's lost play Antiope, Zeus apparently took the form of a satyr to sleep with Antiope.[134] Various authors speak of Zeus raping Callisto, one of the companions of Artemis, doing so in the form of Artemis herself according to Ovid (or, as mentioned by Apollodorus, in the form of Apollo),[135] and Pherecydes relates that Zeus sleeps with Alcmene, the wife of Amphitryon, in the form of her own husband.[136] Several accounts state that Zeus approached the Argive princess Danae in the form of a shower of gold,[137] and according to Ovid he abducts Aegina in the form of a flame.[138]

In accounts of Zeus's affairs, Hera is often depicted as a jealous wife, with there being various stories of her persecuting either the women with whom Zeus sleeps, or their children by him.[139] Several authors relate that Zeus sleeps with Io, a priestess of Hera, who is subsequently turned into a cow, and suffers at Hera's hands: according to Apollodorus, Hera sends a gadfly to sting the cow, driving her all the way to Egypt, where she is finally transformed back into human form.[140] In later accounts of Zeus's affair with Semele, a daughter of Cadmus and Harmonia, Hera tricks her into persuading Zeus to grant her any promise. Semele asks him to come to her as he comes to his own wife Hera, and when Zeus upholds this promise, she dies out of fright and is reduced to ashes.[141] According to Callimachus, after Zeus sleeps with Callisto, Hera turns her into a bear, and instructs Artemis to shoot her.[142] In addition, Zeus's son by Alcmene, the hero Heracles, is persecuted continuously throughout his mortal life by Hera, up until his apotheosis.[143]

According to Diodorus Siculus, Alcmene, the mother of Heracles, was the very last mortal woman Zeus ever slept with; following the birth of Heracles, he ceased to beget humans altogether, and fathered no more children.[144]

List of disguises used by Zeus

[edit]| Disguise | When desiring | |

|---|---|---|

| Eagle or flame of fire | Aegina | [145] |

| Amphitryon | Alcmene | [146] |

| Satyr | Antiope | [147] |

| Artemis or Apollo | Callisto | [148] |

| Shower of gold | Danaë | [149] |

| Bull | Europa | [150] |

| Eagle | Ganymede | [151] |

| Cuckoo | Hera | [152] |

| Swan | Leda | [153] |

| Goose | Nemesis | [154] |

Offspring

[edit]The following is a list of Zeus's offspring, by various mothers. Beside each offspring, the earliest source to record the parentage is given, along with the century to which the source dates.

Prometheus and conflicts with humans

[edit]

When the gods met at Mecone to discuss which portions they will receive after a sacrifice, the titan Prometheus decided to trick Zeus so that humans receive the better portions. He sacrificed a large ox, and divided it into two piles. In one pile he put all the meat and most of the fat, covering it with the ox's grotesque stomach, while in the other pile, he dressed up the bones with fat. Prometheus then invited Zeus to choose; Zeus chose the pile of bones. This set a precedent for sacrifices, where humans will keep the fat for themselves and burn the bones for the gods.

Zeus, enraged at Prometheus's deception, prohibited the use of fire by humans. Prometheus, however, stole fire from Olympus in a fennel stalk and gave it to humans. This further enraged Zeus, who punished Prometheus by binding him to a cliff, where an eagle constantly ate Prometheus's liver, which regenerated every night. Prometheus was eventually freed from his misery by Heracles.[253]

Now Zeus, angry at humans, decides to give humanity a punishing gift to compensate for the boon they had been given. He commands Hephaestus to mold from earth the first woman, a "beautiful evil" whose descendants would torment the human race. After Hephaestus does so, several other gods contribute to her creation. Hermes names the woman 'Pandora'.

Pandora was given in marriage to Prometheus's brother Epimetheus. Zeus gave her a jar which contained many evils. Pandora opened the jar and released all the evils, which made mankind miserable. Only hope remained inside the jar.[254]

When Zeus was atop Mount Olympus he was appalled by human sacrifice and other signs of human decadence. He decided to wipe out mankind and flooded the world with the help of his brother Poseidon. After the flood, only Deucalion and Pyrrha remained.[255] This flood narrative is a common motif in mythology.[256]

In the Iliad

[edit]

| Trojan War |

|---|

|

- ^ Attic–Ionic Greek: Ζεύς, romanized: Zeús Attic–Ionic Greek: [zděu̯s] or [dzěu̯s], Koine Greek pronunciation: [zeʍs], Modern Greek pronunciation: [zefs]; genitive: Δῐός, romanized: Diós [di.ós]

Boeotian Aeolic and Laconian Doric Greek: Δεύς, romanized: Deús Doric Greek: [děu̯s]; genitive: Δέος, romanized: Déos [dé.os]

Greek: Δίας, romanized: Días Modern Greek: [ˈði.as̠]

The Iliad is an ancient Greek epic poem attributed to Homer about the Trojan War and the battle over the City of Troy, in which Zeus plays a major part.

Scenes in which Zeus appears include:[257][258]

- Book 2: Zeus sends Agamemnon a dream and is able to partially control his decisions because of the effects of the dream

- Book 4: Zeus promises Hera to ultimately destroy the City of Troy at the end of the war

- Book 7: Zeus and Poseidon ruin the Achaeans fortress

- Book 8: Zeus prohibits the other Gods from fighting each other and has to return to Mount Ida where he can think over his decision that the Greeks will lose the war

- Book 14: Zeus is seduced by Hera and becomes distracted while she helps out the Greeks

- Book 15: Zeus wakes up and realizes that his own brother, Poseidon has been aiding the Greeks, while also sending Hector and Apollo to help fight the Trojans ensuring that the City of Troy will fall

- Book 16: Zeus is upset that he could not help save Sarpedon's life because it would then contradict his previous decisions

- Book 17: Zeus is emotionally hurt by the fate of Hector

- Book 20: Zeus lets the other Gods lend aid to their respective sides in the war

- Book 24: Zeus demands that Achilles release the corpse of Hector to be buried honourably

Other myths

[edit]When Hades requested to marry Zeus's daughter, Persephone, Zeus approved and advised Hades to abduct Persephone, as her mother Demeter would not allow her to marry Hades.[259]

In the Orphic "Rhapsodic Theogony" (first century BC/AD),[260] Zeus wanted to marry his mother Rhea. After Rhea refused to marry him, Zeus turned into a snake and raped her. Rhea became pregnant and gave birth to Persephone. Zeus in the form of a snake would mate with his daughter Persephone, which resulted in the birth of Dionysus.[261]

Zeus granted Callirrhoe's prayer that her sons by Alcmaeon, Acarnan and Amphoterus, grow quickly so that they might be able to avenge the death of their father by the hands of Phegeus and his two sons.[262]

Both Zeus and Poseidon wooed Thetis, daughter of Nereus. But when Themis (or Prometheus) prophesied that the son born of Thetis would be mightier than his father, Thetis was married off to the mortal Peleus.[263][264]

Zeus was afraid that his grandson Asclepius would teach resurrection to humans, so he killed Asclepius with his thunderbolt. This angered Asclepius's father, Apollo, who in turn killed the Cyclopes who had fashioned the thunderbolts of Zeus. Angered at this, Zeus would have imprisoned Apollo in Tartarus. However, at the request of Apollo's mother, Leto, Zeus instead ordered Apollo to serve as a slave to King Admetus of Pherae for a year.[265] According to Diodorus Siculus, Zeus killed Asclepius because of complains from Hades, who was worried that the number of people in the underworld was diminishing because of Asclepius's resurrections.[266]

The winged horse Pegasus carried the thunderbolts of Zeus.[267]

Zeus took pity on Ixion, a man who was guilty of murdering his father-in-law, by purifying him and bringing him to Olympus. However, Ixion started to lust after Hera. Hera complained about this to her husband, and Zeus decided to test Ixion. Zeus fashioned a cloud that resembles Hera (Nephele) and laid the cloud-Hera in Ixion's bed. Ixion coupled with Nephele, resulting in the birth of Centaurus. Zeus punished Ixion for lusting after Hera by tying him to a wheel that spins forever.[268]

Once, Helios the sun god gave his chariot to his inexperienced son Phaethon to drive. Phaethon could not control his father's steeds so he ended up taking the chariot too high, freezing the earth, or too low, burning everything to the ground. The earth itself prayed to Zeus, and in order to prevent further disaster, Zeus hurled a thunderbolt at Phaethon, killing him and saving the world from further harm.[269] In a satirical work, Dialogues of the Gods by Lucian, Zeus berates Helios for allowing such thing to happen; he returns the damaged chariot to him and warns him that if he dares do that again, he will strike him with one of this thunderbolts.[270]

Roles and epithets

[edit]

Zeus played a dominant role, presiding over the Greek Olympian pantheon. He fathered many of the heroes and was featured in many of their local cults. Though the Homeric "cloud collector" was the god of the sky and thunder like his Near-Eastern counterparts, he was also the supreme cultural artifact; in some senses, he was the embodiment of Greek religious beliefs and the archetypal Greek deity.

Popular conceptions of Zeus differed widely from place to place. Local varieties of Zeus often have little in common with each other except the name. They exercised different areas of authority and were worshiped in different ways; for example, some local cults conceived of Zeus as a chthonic earth-god rather than a god of the sky. These local divinities were gradually consolidated, via conquest and religious syncretism, with the Homeric conception of Zeus. Local or idiosyncratic versions of Zeus were given epithets — surnames or titles which distinguish different conceptions of the god.[29]

These epithets or titles applied to Zeus emphasized different aspects of his wide-ranging authority:

- Zeus Aegiduchos or Aegiochos: Usually taken as Zeus as the bearer of the Aegis, the divine shield with the head of Medusa across it,[272] although others derive it from "goat" (αἴξ) and okhē (οχή) in reference to Zeus's nurse, the divine goat Amalthea.[273][274]

- Zeus Agoraeus (Ἀγοραῖος): Zeus as patron of the marketplace (agora) and punisher of dishonest traders.

- Zeus Areius (Αρειος): either "warlike" or "the atoning one".

- Zeus Eleutherios (Ἐλευθέριος): "Zeus the freedom giver" a cult worshiped in Athens[275]

- Zeus Horkios: Zeus as keeper of oaths. Exposed liars were made to dedicate a votive statue to Zeus, often at the sanctuary at Olympia

- Zeus Olympios (Ολύμπιος): Zeus as king of the gods and patron of the Panhellenic Games at Olympia

- Zeus Panhellenios ("Zeus of All the Greeks"): worshipped at Aeacus's temple on Aegina

- Zeus Xenios (Ξένιος), Philoxenon, or Hospites: Zeus as the patron of hospitality (xenia) and guests, avenger of wrongs done to strangers

Cults

[edit]

Panhellenic cults

[edit]

The major center where all Greeks converged to pay honor to their chief god was Olympia. Their quadrennial festival featured the famous Games. There was also an altar to Zeus made not of stone, but of ash, from the accumulated remains of many centuries' worth of animals sacrificed there.

Outside of the major inter-polis sanctuaries, there were no modes of worshipping Zeus precisely shared across the Greek world. Most of the titles listed below, for instance, could be found at any number of Greek temples from Asia Minor to Sicily. Certain modes of ritual were held in common as well: sacrificing a white animal over a raised altar, for instance.

Zeus Velchanos

[edit]With one exception, Greeks were unanimous in recognizing the birthplace of Zeus as Crete. Minoan culture contributed many essentials of ancient Greek religion: "by a hundred channels the old civilization emptied itself into the new", Will Durant observed,[278] and Cretan Zeus retained his youthful Minoan features. The local child of the Great Mother, "a small and inferior deity who took the roles of son and consort",[279] whose Minoan name the Greeks Hellenized as Velchanos, was in time assumed as an epithet by Zeus, as transpired at many other sites, and he came to be venerated in Crete as Zeus Velchanos ("boy-Zeus"), often simply the Kouros.

In Crete, Zeus was worshipped at a number of caves at Knossos, Ida and Palaikastro. In the Hellenistic period a small sanctuary dedicated to Zeus Velchanos was founded at the Hagia Triada site of an earlier Minoan town. Broadly contemporary coins from Phaistos show the form under which he was worshiped: a youth sits among the branches of a tree, with a cockerel on his knees.[280] On other Cretan coins Velchanos is represented as an eagle and in association with a goddess celebrating a mystic marriage.[281] Inscriptions at Gortyn and Lyttos record a Velchania festival, showing that Velchanios was still widely venerated in Hellenistic Crete.[282]

The stories of Minos and Epimenides suggest that these caves were once used for incubatory divination by kings and priests. The dramatic setting of Plato's Laws is along the pilgrimage-route to one such site, emphasizing archaic Cretan knowledge. On Crete, Zeus was represented in art as a long-haired youth rather than a mature adult and hymned as ho megas kouros, "the great youth". Ivory statuettes of the "Divine Boy" were unearthed near the Labyrinth at Knossos by Sir Arthur Evans.[283] With the Kouretes, a band of ecstatic armed dancers, he presided over the rigorous military-athletic training and secret rites of the Cretan paideia.

The myth of the death of Cretan Zeus, localised in numerous mountain sites though only mentioned in a comparatively late source, Callimachus,[284] together with the assertion of Antoninus Liberalis that a fire shone forth annually from the birth-cave the infant shared with a mythic swarm of bees, suggests that Velchanos had been an annual vegetative spirit.[285] The Hellenistic writer Euhemerus apparently proposed a theory that Zeus had actually been a great king of Crete and that posthumously, his glory had slowly turned him into a deity. The works of Euhemerus himself have not survived, but Christian patristic writers took up the suggestion.

Zeus Lykaios

[edit]

The epithet Zeus Lykaios (Λύκαιος; "wolf-Zeus") is assumed by Zeus only in connection with the archaic festival of the Lykaia on the slopes of Mount Lykaion ("Wolf Mountain"), the tallest peak in rustic Arcadia; Zeus had only a formal connection[286] with the rituals and myths of this primitive rite of passage with an ancient threat of cannibalism and the possibility of a werewolf transformation for the ephebes who were the participants.[287] Near the ancient ash-heap where the sacrifices took place[288] was a forbidden precinct in which, allegedly, no shadows were ever cast.[289]

According to Plato,[290] a particular clan would gather on the mountain to make a sacrifice every nine years to Zeus Lykaios, and a single morsel of human entrails would be intermingled with the animal's. Whoever ate the human flesh was said to turn into a wolf, and could only regain human form if he did not eat again of human flesh until the next nine-year cycle had ended. There were games associated with the Lykaia, removed in the fourth century to the first urbanization of Arcadia, Megalopolis; there the major temple was dedicated to Zeus Lykaios.

There is, however, the crucial detail that Lykaios or Lykeios (epithets of Zeus and Apollo) may derive from Proto-Greek *λύκη, "light", a noun still attested in compounds such as ἀμφιλύκη, "twilight", λυκάβας, "year" (lit. 'light's course") etc. This, Cook argues, brings indeed much new 'light' to the matter as Achaeus, the contemporary tragedian of Sophocles, spoke of Zeus Lykaios as "starry-eyed", and this Zeus Lykaios may just be the Arcadian Zeus, son of Aether, described by Cicero. Again under this new signification may be seen Pausanias's descriptions of Lykosoura being 'the first city that ever the sun beheld', and of the altar of Zeus, at the summit of Mount Lykaion, before which stood two columns bearing gilded eagles and 'facing the sun-rise'. Further Cook sees only the tale of Zeus's sacred precinct at Mount Lykaion allowing no shadows referring to Zeus as 'god of light' (Lykaios).[291]

Additional cults

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2021) |

Although etymology indicates that Zeus was originally a sky god, many Greek cities honored a local Zeus who lived underground. Athenians and Sicilians honored Zeus Meilichios (Μειλίχιος; "kindly" or "honeyed") while other cities had Zeus Chthonios ("earthy"), Zeus Katachthonios (Καταχθόνιος; "under-the-earth") and Zeus Plousios ("wealth-bringing"). These deities might be represented as snakes or in human form in visual art, or, for emphasis as both together in one image. They also received offerings of black animal victims sacrificed into sunken pits, as did chthonic deities like Persephone and Demeter, and also the heroes at their tombs. Olympian gods, by contrast, usually received white victims sacrificed upon raised altars.

In some cases, cities were not entirely sure whether the daimon to whom they sacrificed was a hero or an underground Zeus. Thus the shrine at Lebadaea in Boeotia might belong to the hero Trophonius or to Zeus Trephonius ("the nurturing"), depending on whether you believe Pausanias, or Strabo. The hero Amphiaraus was honored as Zeus Amphiaraus at Oropus outside of Thebes, and the Spartans even had a shrine to Zeus Agamemnon. Ancient Molossian kings sacrificed to Zeus Areius (Αρειος). Strabo mention that at Tralles there was the Zeus Larisaeus (Λαρισαιος).[292] In Ithome, they honored the Zeus Ithomatas, they had a sanctuary and a statue of Zeus and also held an annual festival in honour of Zeus which was called Ithomaea (ἰθώμαια).[293]

Hecatomphonia

[edit]Hecatomphonia (Ancient Greek: ἑκατομφόνια), meaning killing of a hundred, from ἑκατόν "a hundred" and φονεύω "to kill". It was a custom of Messenians, at which they offered sacrifice to Zeus when any of them had killed a hundred enemies. Aristomenes have offered three times this sacrifice at the Messenian wars against Sparta.[294][295][296][297]

Non-panhellenic cults

[edit]

In addition to the Panhellenic titles and conceptions listed above, local cults maintained their own idiosyncratic ideas about the king of gods and men. With the epithet Zeus Aetnaeus he was worshiped on Mount Aetna, where there was a statue of him, and a local festival called the Aetnaea in his honor.[298] Other examples are listed below. As Zeus Aeneius or Zeus Aenesius (Αινησιος), he was worshiped in the island of Cephalonia, where he had a temple on Mount Aenos.[299]

Oracles

[edit]Although most oracle sites were usually dedicated to Apollo, the heroes, or various goddesses like Themis, a few oracular sites were dedicated to Zeus. In addition, some foreign oracles, such as Baʿal's at Heliopolis, were associated with Zeus in Greek or Jupiter in Latin.

The Oracle at Dodona

[edit]The cult of Zeus at Dodona in Epirus, where there is evidence of religious activity from the second millennium BC onward, centered on a sacred oak. When the Odyssey was composed (circa 750 BC), divination was done there by barefoot priests called Selloi, who lay on the ground and observed the rustling of the leaves and branches.[300] By the time Herodotus wrote about Dodona, female priestesses called peleiades ("doves") had replaced the male priests.

Zeus's consort at Dodona was not Hera, but the goddess Dione — whose name is a feminine form of "Zeus". Her status as a titaness suggests to some that she may have been a more powerful pre-Hellenic deity, and perhaps the original occupant of the oracle.

The Oracle at Siwa

[edit]The oracle of Ammon at the Siwa Oasis in the Western Desert of Egypt did not lie within the bounds of the Greek world before Alexander's day, but it already loomed large in the Greek mind during the archaic era: Herodotus mentions consultations with Zeus Ammon in his account of the Persian War. Zeus Ammon was especially favored at Sparta, where a temple to him existed by the time of the Peloponnesian War.[301]

After Alexander made a trek into the desert to consult the oracle at Siwa, the figure arose in the Hellenistic imagination of a Libyan Sibyl.

Identifications with other gods

[edit]Foreign gods

[edit]

Zeus was identified with the Roman god Jupiter and associated in the syncretic classical imagination (see interpretatio graeca) with various other deities, such as the Egyptian Ammon and the Etruscan Tinia. He, along with Dionysus, absorbed the role of the chief Phrygian god Sabazios in the syncretic deity known in Rome as Sabazius. The Seleucid ruler Antiochus IV Epiphanes erected a statue of Zeus Olympios in the Judean Temple in Jerusalem.[303] Hellenizing Jews referred to this statue as Baal Shamen (in English, Lord of Heaven).[304] Zeus is also identified with the Hindu deity Indra. Not only they are the king of gods, but their weapon - thunder is similar.[305]

Helios

[edit]Zeus is occasionally conflated with the Hellenic sun god, Helios, who is sometimes either directly referred to as Zeus's eye,[306] or clearly implied as such. Hesiod, for instance, describes Zeus's eye as effectively the sun.[307] This perception is possibly derived from earlier Proto-Indo-European religion, in which the sun is occasionally envisioned as the eye of *Dyḗus Pḥatḗr (see Hvare-khshaeta).[308] Euripides in his now lost tragedy Mysians described Zeus as "sun-eyed", and Helios is said elsewhere to be "the brilliant eye of Zeus, giver of life".[309] In another of Euripides's tragedies, Medea, the chorus refers to Helios as "light born from Zeus."[310]

Although the connection of Helios to Zeus does not seem to have basis in early Greek cult and writings, nevertheless there are many examples of direct identification in later times.[311] The Hellenistic period gave birth to Serapis, a Greco-Egyptian deity conceived as a chthonic avatar of Zeus, whose solar nature is indicated by the sun crown and rays the Greeks depicted him with.[312] Frequent joint dedications to "Zeus-Serapis-Helios" have been found all over the Mediterranean,[312] for example, the Anastasy papyrus (now housed in the British Museum equates Helios to not just Zeus and Serapis but also Mithras,[313] and a series of inscriptions from Trachonitis give evidence of the cult of "Zeus the Unconquered Sun".[314] There is evidence of Zeus being worshipped as a solar god in the Aegean island of Amorgos, based on a lacunose inscription Ζεὺς Ἥλ[ιο]ς ("Zeus the Sun"), meaning sun elements of Zeus's worship could be as early as the fifth century BC.[315]

The Cretan Zeus Tallaios had solar elements to his cult. "Talos" was the local equivalent of Helios.[316]

Later representations

[edit]Philosophy

[edit]In Neoplatonism, Zeus's relation to the gods familiar from mythology is taught as the Demiurge or Divine Mind, specifically within Plotinus's work the Enneads[317] and the Platonic Theology of Proclus.

The Bible

[edit]Zeus is mentioned in the New Testament twice, first in Acts 14:8–13: When the people living in Lystra saw the Apostle Paul heal a lame man, they considered Paul and his partner Barnabas to be gods, identifying Paul with Hermes and Barnabas with Zeus, even trying to offer them sacrifices with the crowd. Two ancient inscriptions discovered in 1909 near Lystra testify to the worship of these two gods in that city.[318] One of the inscriptions refers to the "priests of Zeus", and the other mentions "Hermes Most Great" and "Zeus the sun-god".[319]

The second occurrence is in Acts 28:11: the name of the ship in which the prisoner Paul set sail from the island of Malta bore the figurehead "Sons of Zeus" aka Castor and Pollux (Dioscuri).

The deuterocanonical book of 2 Maccabees 6:1, 2 talks of King Antiochus IV (Epiphanes), who in his attempt to stamp out the Jewish religion, directed that the temple at Jerusalem be profaned and rededicated to Zeus (Jupiter Olympius).[320]

Genealogy

[edit]| Zeus's family tree[321] |

|---|

Gallery

[edit]-

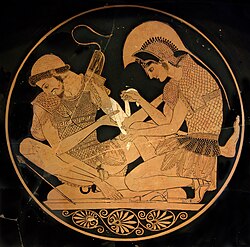

Enthroned Zeus (Greek, c. 100 BC) - modeled after the Olympian Zeus by Pheidas (c. 430 BC)

-

Olympian assembly, from left to right: Apollo, Zeus and Hera

-

The abduction of Europa

-

The "Golden Man" Zeus statue

-

Zeus and Hera

-

1st century BC statue of Zeus[327]

See also

[edit]- Family tree of the Greek gods

- Agetor

- Ambulia – Spartan epithet used for Athena, Zeus, and Castor and Pollux

- Hetairideia – Thessalian Festival to Zeus

- Temple of Zeus, Olympia

- Zanes of Olympia – Statues of Zeus

Footnotes

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The sculpture was presented to Louis XIV as Aesculapius but restored as Zeus, ca. 1686, by Pierre Granier, who added the upraised right arm brandishing the thunderbolt. Marble, middle 2nd century CE. Formerly in the "Allée Royale", (Tapis Vert) in the Gardens of Versailles, now conserved in the Louvre Museum (Official online catalog)

- ^ a b Hamilton, Edith (1942). Mythology (1998 ed.). New York: Back Bay Books. p. 467. ISBN 978-0-316-34114-1.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Hard 2004, p. 79.

- ^ Brill's New Pauly, s.v. Zeus.

- ^ Homer, Il., Book V.

- ^ Plato, Symposium 180e.

- ^ There are two major conflicting stories for Aphrodite's origins: Hesiod's Theogony claims that she was born from the foam of the sea after Cronos castrated Uranus, making her Uranus's daughter, while Homer's Iliad has Aphrodite as the daughter of Zeus and Dione.[5] A speaker in Plato's Symposium offers that they were separate figures: Aphrodite Ourania and Aphrodite Pandemos.[6]

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 886–900.

- ^ Homeric Hymns.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony.

- ^ Burkert, Greek Religion.

- ^ See, e.g., Homer, Il., I.503 & 533.

- ^ Pausanias, 2.24.4.

- ^ Brill's New Pauly, s.v. Zeus.

- ^ Νεφεληγερέτα. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ^ Laërtius, Diogenes (1972) [1925]. "1.11". In Hicks, R. D. (ed.). Lives of Eminent Philosophers. "1.11". Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers (in Greek).

- ^ "The Linear B word di-we". "The Linear B word di-wo". Palaeolexicon: Word study tool of Ancient languages.

- ^ a b "Zeus". American Heritage Dictionary. Retrieved 3 July 2006.

- ^ Robert S. P. Beekes, Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Brill Publishers, 2009, p. 499.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "Jupiter". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Hyllested, Adam; Joseph, Brian D. (2022). "Albanian". In Olander, Thomas (ed.). The Indo-European Language Family: A Phylogenetic Perspective. Cambridge University Press. p. 232. doi:10.1017/9781108758666. ISBN 9781108758666. S2CID 161016819.

- ^ Søborg, Tobias Mosbæk (2020). Sigmatic Verbal Formations in Anatolian and Indo-European: A Cladistic Study (Thesis). University of Copenhagen, Department of Nordic Studies and Linguistics. p. 74..

- ^ Burkert (1985). Greek Religion. Harvard University Press. p. 321. ISBN 0-674-36280-2.

- ^ "Plato's Cratylus" by Plato, ed. by David Sedley, Cambridge University Press, 6 November 2003, p. 91

- ^ Jevons, Frank Byron (1903). The Makers of Hellas. C. Griffin, Limited. pp. 554–555.

- ^ Joseph, John Earl (2000). Limiting the Arbitrary. John Benjamins. ISBN 1556197497.

- ^ "Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica, Books I-V, book 5, chapter 72". www.perseus.tufts.edu.

- ^ Lactantius, Divine Institutes 1.11.1.

- ^ a b Hewitt, Joseph William (1908). "The Propitiation of Zeus". Harvard Studies in Classical Philology. 19: 61–120. doi:10.2307/310320. JSTOR 310320.

- ^ See Gantz, pp. 10–11; Hesiod, Theogony 159–83.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 67; Hansen, p. 67; Tripp, s.v. Zeus, p. 605; Caldwell, p. 9, table 12; Hesiod, Theogony 453–8. So too Apollodorus, 1.1.5; Diodorus Siculus, 68.1.

- ^ Gantz, p. 41; Hard 2004, p. 67–8; Grimal, s.v. Zeus, p. 467; Hesiod, Theogony 459–67. Compare with Apollodorus, 1.1.5, who gives a similar account, and Diodorus Siculus, 70.1–2, who does not mention Cronus's parents, but rather says that it was an oracle who gave the prophecy.

- ^ Cf. Apollodorus, 1.1.6, who says that Rhea was "enraged".

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 68; Gantz, p. 41; Smith, s.v. Zeus; Hesiod, Theogony 468–73.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 74; Gantz, p. 41; Hesiod, Theogony 474–9.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 74; Hesiod, Theogony 479–84. According to Hard 2004, the "otherwise unknown" Mount Aegaeon can "presumably ... be identified with one of the various mountains near Lyktos".

- ^ Hansen, p. 67; Hard 2004, p. 68; Smith, s.v. Zeus; Gantz, p. 41; Hesiod, Theogony 485–91. For iconographic representations of this scene, see Louvre G 366; Clark, p. 20, figure 2.1 and Metropolitan Museum of Art 06.1021.144; LIMC 15641; Beazley Archive 214648. According to Pausanias, 9.41.6, this event occurs at Petrachus, a "crag" nearby to Chaeronea (see West 1966, p. 301 on line 485).

- ^ West 1966, p. 291 on lines 453–506; Hard 2004, p. 75.

- ^ Fowler 2013, pp. 35, 50; Eumelus fr. 2 West, pp. 224, 225 [= fr. 10 Fowler, p. 109 = PEG fr. 18 (Bernabé, p. 114) = Lydus, De Mensibus 4.71]. According to West 2003, p. 225 n. 3, in this version he was born "probably on Mt. Sipylos".

- ^ Fowler 2013, p. 391; Grimal, s.v. Zeus, p. 467; Callimachus, Hymn to Zeus (1) 4–11 (pp. 36–9).

- ^ Fowler 2013, p. 391; Diodorus Siculus, 70.2, 70.6.

- ^ Apollodorus, 1.1.6.

- ^ "Pausanias, Description of Greece, Messenia, chapter 33, section 1". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 18 March 2025.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 133–8, 453–8 (Most, pp. 12, 13, 38, 39); Caldwell, p. 4, table 2, p. 9, table 12.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 68; Gantz, p. 41; Hesiod, Theogony 492–3: "the strength and glorious limbs of the prince increased quickly".

- ^ West 1983, p. 122; Apollodorus, 1.1.6.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 612 n. 53 to p. 75; Apollodorus, 1.1.7.

- ^ Hansen, p. 216; Apollodorus, 1.1.7.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus, 7.70.2; see also 7.65.4.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus, 7.70.2–3.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus, 7.65.4.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus, 7.70.4.

- ^ Gantz, p. 42; Hyginus, Fabulae 139.

- ^ Gantz, p. 42; Hard 2004, p. 75; Hyginus, Fabulae 139.

- ^ Smith and Trzaskoma, p. 191 on line 182; West 1983, p. 133 n. 40; Hyginus, Fabulae 182 (Smith and Trzaskoma, p. 158).

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 75–6; Gantz, p. 42; Epimenides fr. 23 Diels, p. 193 [= Scholia on Aratus, 46]. Zeus later marks the event by placing the constellations of the Dragon, the Greater Bear and the Lesser Bear in the sky.

- ^ Gantz, p. 41; Gee, p. 131–2; Frazer, p. 120; Musaeus fr. 8 Diels, pp. 181–2 [= Eratosthenes, Catasterismi 13 (Hard 2015, p. 44; Olivieri, p. 17)]; Musaeus apud Hyginus, De astronomia 2.13.6. According to Eratosthenes, Musaeus considers the she-goat to be a child of Helios, and to be "so terrifying to behold" that the Titans ask for it to be hidden in one of the caves in Crete; hence Earth places it in the care of Amalthea, who nurses Zeus on its milk.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 75; Antoninus Liberalis, 19.

- ^ Gantz, p. 44; Hard 2004, p. 68; Hesiod, Theogony 492–7.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 68; Hesiod, Theogony 498–500.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 68; Gantz, p. 44; Hesiod, Theogony 501–6. The Cyclopes presumably remained trapped below the earth since being put there by Uranus (Hard 2004, p. 68).

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 68; Gantz, p. 45; Hesiod, Theogony 630–4.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 68; Hesiod, Theogony 624–9, 635–8. As Gantz, p. 45 notes, the Theogony is ambiguous as to whether the Hundred-Handers were freed before the war or only during its tenth year.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 639–53.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 654–63.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 687–735.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 69; Gantz, p. 44; Apollodorus, 1.2.1.

- ^ a b Hard 2004, p. 69; Apollodorus, 1.2.1.

- ^ Gantz, p. 48; Hard 2004, p. 76; Brill's New Pauly, s.v. Zeus; Homer, Iliad 15.187–193; so too Apollodorus, 1.2.1; cf. Homeric Hymn to Demeter (2), 85–6.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 86; Hesiod, Theogony 183–7.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 86; Gantz, p. 446.

- ^ Gantz, p. 449; Hard 2004, p. 90; Apollodorus, 1.6.1.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 89; Gantz, p. 449; Apollodorus, 1.6.1.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 89; Gantz, p. 449; Salowey, p. 236; Apollodorus, 1.6.2. Compare with Pindar, Pythian 8.12–8, who instead says that Porphyrion is killed by an arrow from Apollo.

- ^ Ogden, pp. 72–3; Gantz, p. 48; Fontenrose, p. 71; Fowler, p. 27; Hesiod, Theogony 820–2. According to Ogden, Gaia "produced him in revenge against Zeus for his destruction of ... the Titans". Contrastingly, according to the Homeric Hymn to Apollo (3), 305–55, Hera is the mother of Typhon without a father: angry at Zeus for birthing Athena by himself, she strikes the ground with her hand, praying to Gaia, Uranus, and the Titans to give her a child more powerful than Zeus, and receiving her wish, she bears the monster Typhon (Fontenrose, p. 72; Gantz, p. 49; Hard 2004, p. 84); cf. Stesichorus fr. 239 Campbell, pp. 166, 167 [= PMG 239 (Page, p. 125) = Etymologicum Magnum 772.49] (see Gantz, p. 49).

- ^ Gantz, p. 49; Hesiod, Theogony 824–8.

- ^ Fontenrose, p. 71; Hesiod, Theogony 836–8.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 839–68. According to Fowler, p. 27, the monster's easy defeat at the hands of Zeus is "in keeping with Hesiod's pervasive glorification of Zeus".

- ^ Ogden, p. 74; Gantz, p. 49; Epimenides fr. 10 Fowler, p. 97 [= fr. 8 Diels, p. 191 = FGrHist 457 F8].

- ^ Fontenrose, p. 73; Aeschylus, Prometheus Bound 356–64; Pindar, Olympian 8.16–7; for a discussion of Aeschylus's and Pindar's accounts, see Gantz, p. 49.

- ^ Apollodorus, 1.6.3.

- ^ Gantz, p. 50; Fontenrose, p. 73.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 84; Fontenrose, p. 73; Gantz, p. 50.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 84; Fontenrose, p. 73.

- ^ Fontenrose, p. 73; Ogden, p. 42; Hard 2004, p. 84.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 84–5; Fontenrose, p. 73–4.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 85.

- ^ Ogden, p. 74–5; Fontenrose, pp. 74–5; Lane Fox, p. 287; Gantz, p. 50.

- ^ Gantz, p. 59; Hard 2004, p. 82; Homer, Iliad 1.395–410.

- ^ Gantz, p. 51; Hard 2004, p. 77; Hesiod, Theogony 886–900. Yasumura, p. 90 points out that the identity of the foretold son's father is not made clear by Hesiod, and suggests, drawing upon a version given by a scholiast on the Iliad (see below), that a possible interpretation would be that the Cyclops Brontes was the father.

- ^ Smith, s.v. Metis; Apollodorus, 1.3.6.

- ^ Potentially from the Melampodia (Hard 2004, p. 77).

- ^ Gantz, p. 51; Hard 2004, p. 77; Hesiod fr. 294 Most, pp. 390–3 [= fr. 343 Merkelbach-West, p. 171 = Chrysippus fr. 908 Arnim, p. 257 = Galen, On the Doctrines of Hippocrates and Plato 3.8.11–4 (p. 226)].

- ^ Gantz, p. 51; Yasumura, p. 89; Scholia bT on Homer's Iliad, 8.39 (Yasumura, p. 89).

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 77. Compare with Gantz, p. 51, who sees the myth as a conflation of three separate elements: one in which Athena is born from Zeus's head, one in which Zeus consumes Metis so as to obtain her wisdom, and one in which he swallows her so as to avoid the threat of the prophesied son.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 77–8; see also Yasumura, p. 90.

- ^ Gantz, p. 51; Hard 2004, p. 78; Hesiod, Theogony 901–6. Earlier, at 217, Hesiod instead calls the Moirai daughters of Nyx.

- ^ Gantz, p. 52; Hard 2004, p. 78; Pindar fr. 30 Race, pp. 236, 237 [= Clement of Alexandria, Stromata 5.14.137.1].

- ^ Gantz, p. 54; Hard 2004, p. 78; Hesiod, Theogony 907–11.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 78; Hansen, p. 68; Hesiod, Theogony 912–4.

- ^ Gantz, p. 54; Hesiod, Theogony 53–62, 915–7.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 78; Hesiod, Theogony 918–20; Homeric Hymn to Apollo (3), 89–123. The account given by the Homeric Hymn to Apollo differs from Hesiod's version in that Zeus and Hera are already married when Apollo and Artemis are born (Pirenne-Delforge and Pironti, p. 18).

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 921.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 886–920 (Most, pp. 74–77); Caldwell, p. 11, table 14.

- ^ a b One of the Oceanid daughters of Oceanus and Tethys, at 358.

- ^ Of Zeus's children by his partners before Hera, Athena was the first to be conceived (889), but the last to be born. Zeus impregnated Metis then swallowed her, later Zeus himself gave birth to Athena "from his head" (924).

- ^ At 217 the Moirai are the daughters of Nyx.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 78.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 79; Hesiod, Theogony 921–3; so too Apollodorus, 1.3.1. In the Iliad, Eris is called the sister of Ares (4.440–1), and Parada, s.v. Eris, p. 72 places her as a daughter of Zeus and Hera.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 79; Gantz, p. 74; Hesiod, Theogony 924–9; so too Apollodorus, 1.3.5.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 79; Gantz, p. 74; Homer, Iliad 1.577–9, 14.293–6, 14.338, Odyssey 8.312; Scholia bT on Homer's Iliad, 14.296; see also Apollodorus, 1.3.5.

- ^ Gantz, p. 57; Pirenne-Delforge and Pironti, p. 24; Hard 2004, pp. 78, 136; Homer, Iliad 14.293–6. Gantz points out that, if in this version Cronus swallows his children as he does in the Theogony, the pair could not sleep with each other without their father's knowledge before Zeus overthrows Cronus, and so suggests that Homer may have possibly been following a version of the story in which only Cronus's sons are swallowed.

- ^ Gantz, p. 57; Scholia bT on Homer's Iliad, 14.296. Cf. Scholia A on Homer's Iliad, 1.609 (Dindorf 1875a, p. 69); see Pirenne-Delforge and Pironti, p. 20; Hard 2004, p. 136.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 136; Callimachus, fr. 48 Harder, pp. 152, 153 [= Scholia A on Homer's Iliad, 1.609 (Dindorf 1875a, p. 69)]; see also Pirenne-Delforge and Pironti, p. 20.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 137; Scholia on Theocritus, 15.64 (Wendel, pp. 311–2) [= FGrHist 33 F3]; Gantz, p. 58. The scholiast attributes the story to the work On the Cults of Hermione, by an Aristocles.

- ^ BNJ, commentary on 33 F3; Pausanias, 2.17.4, 2.36.1.

- ^ According to Sandbach, Macris is another name for Euboea, who Plutarch calls Hera's nurse at Moralia 657 E (pp. 268–71) (Sandbach, p. 289, note b to fr. 157).

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 137; Plutarch fr. 157 Sandbach, pp. 286–9 [= FGrHist 388 F1 = Eusebius, Praeparatio evangelica 3.1.3 (Gifford 1903a, pp. 112–3; Gifford 1903b, p. 92)].

- ^ Ptolemy Hephaestion apud Photius, Bibliotheca 190.47 (Harry, pp. 68–9; English translation).

- ^ Stephanus of Byzantium s.v. Hermion (II pp. 160, 161).

- ^ Hard 2004, pp. 136–7; Callimachus fr. 75 Clayman, pp. 208–17 [= P. Oxy. 1011 fr. 1 (Grenfell and Hunt, pp. 24–6)]. Callimachus seems to refer to some form of liaison between Zeus and Hera while describing a Naxian premarital ritual; see Hard 2004, pp. 136–7; Gantz, p. 58. Cf. Scholia on Homer's Iliad, 14.296; for a discussion on the relation between the Callimachus fragment and the passage from the scholion, see Sistakou, p. 377.

- ^ Gantz, p. 58; FGrHist 3 F16a [= Scholia on Apollonius of Rhodes' Argonautica 4.1396–9b (Wendel, pp. 315–6)]; FGrHist 3 F16b [= Scholia on Apollonius of Rhodes' Argonautica 2.992 (Wendel, p. 317)].

- ^ Fowler 2013, p. 292; Eratosthenes, Catasterismi 3 (Hard 2015, p. 12; Olivieri, pp. 3–4) [= Hyginus, De astronomia 2.3.1 = FGrHist 3 F16c].

- ^ Apollodorus, 2.5.11.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 136; Diodorus Siculus, 5.72.4.

- ^ Varro apud Lactantius, Divine Institutes 1.17.1 (p. 98).

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 137–8; Pirenne-Delforge and Pironti, p. 99; Pausanias, 9.3.1–2.

- ^ Plutarch fr. 157 Sandbach, pp. 292, 293 [= FGrHist 388 F1 = Eusebius, Praeparatio evangelica 3.1.6 (Gifford 1903a, pp. 114–5; Gifford 1903b, p. 93)].

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 921–9 (Most, pp. 76, 77); Caldwell, p. 12, table 14.

- ^ According to Hesiod, Hera produces Hephaestus on her own, without a father (Theogony 927–9). In the Iliad and the Odyssey, however, he is the son of Zeus and Hera; see Gantz, p. 74; Homer, Iliad 1.577–9, 14.293–6, 14.338, Odyssey 8.312.

- ^ Grimal, s.v. Zeus, p. 468 calls his affairs "countless".

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 337; Gantz, p. 210; Scholia Ab on Homer's Iliad, 12.292 (Dindorf 1875a, pp. 427–8) [= Hesiod fr. 89 Most, pp. 172–5 = Merkelbach-West fr. 140, p. 68] [= Bacchylides fr. 10 Campbell, pp. 262, 263].

- ^ Gantz, pp. 320–1; Hard 2004, p. 439; Euripides, Helen 16–21 (pp. 14, 15).

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 303; Euripides fr. 178 Nauck, pp. 410–2.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 541; Gantz, p. 726; Ovid, Metamorphoses 2.409–530; see also Amphis apud Hyginus, De astronomia 2.1.2. According to Apollodorus, 3.8.2 he took the form "as some say, of Artemis, or, as others say, of Apollo".

- ^ Gantz, p. 375; FGrHist 3 F13b [= Scholia on Homer's Odyssey, 11.266]; FGrHist 3 F13c [= Scholia on Homer's Iliad, 14.323 (Dindorf 1875b, p. 62)].

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 238; Gantz, p. 300; Pindar, Pythian 12.17–8; Apollodorus, 2.4.1; FGrHist 3 F10 [= Scholia on Apollonius of Rhodes' Argonautica, 4.1091 (Wendel, p. 305)].

- ^ Gantz, p. 220; Ovid, Metamorphoses 6.113. In contrast, Nonnus, Dionysiaca 7.122 (pp. 252, 253), 7.210–4 (pp. 260, 261) states that he takes the form of an eagle.

- ^ Gantz, p. 61; Hard 2004, p. 138.

- ^ Gantz, p. 199; Hard 2004, p. 231; Apollodorus, 2.1.3.

- ^ Hard 2004, pp. 170–1; Gantz, p. 476.

- ^ Gantz, p. 726.

- ^ Grimal, s.v. Hera, p. 192; Tripp, s.v. Hera, p. 274.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus, Library of History 4.14.4.

- ^ Gantz, p. 220.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 247; Apollodorus, 2.4.8.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 303; Brill's New Pauly, s.v. Antiope; Scholia on Apollonius of Rhodes, 4.1090.

- ^ Gantz, p. 726; Brill's New Pauly, s.v. Callisto; Grimal, s.v. Callisto, p. 86; Apollodorus, 3.8.2 (Artemis or Apollo); Ovid, Metamorphoses 2.401–530; Hyginus, De astronomia 2.1.2.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 238

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 337; Lane Fox, p. 199.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 522; Ovid, Metamorphoses 10.155–6; Lucian, Dialogues of the Gods 10 (4).

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 137

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 439; Euripides, Helen 16–22.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 438; Cypria fr. 10 West, pp. 88–91 [= Athenaeus, Deipnosophists 8.334b–d].

- ^ Hard 2004, p.244; Hesiod, Theogony 943.

- ^ Hansen, p. 68; Hard 2004, p. 78; Hesiod, Theogony 912.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 78; Hesiod, Theogony 901–911; Hansen, p. 68.

- ^ West 1983, p. 73; Orphic Hymn to the Graces (60), 1–3 (Athanassakis and Wolkow, p. 49).

- ^ Cornutus, Compendium Theologiae Graecae, 15 (Torres, pp. 15–6).

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 79; Hesiod, Theogony 921.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 78; Hesiod, Theogony 912–920; Morford, p. 211.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 80; Hesiod, Theogony 938.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 77; Hesiod, Theogony 886–900.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 78; Hesiod, Theogony 53–62; Gantz, p. 54.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 80; Hesiod, Theogony 940.

- ^ a b Hesiod, Theogony 901–905; Gantz, p. 52; Hard 2004, p. 78.

- ^ Homer, Iliad 5.370; Apollodorus, 1.3.1

- ^ Homer, Iliad 14.319–20; Smith, s.v. Perseus (1).

- ^ Homer, Iliad 14.317–18; Smith, s.v. Peirithous.

- ^ Gantz, p. 210; Brill's New Pauly, s.v. Minos; Homer, Iliad 14.32–33; Hesiod, Catalogue of Women fr. 89 Most, pp. 172–5 [= fr. 140 Merkelbach-West, p. 68].

- ^ Homer, Iliad 14.32–33; Hesiod, Catalogue of Women fr. 89 Most, pp. 172–5 [= fr. 140 Merkelbach-West, p. 68]; Gantz, p. 210; Smith, s.v. Rhadamanthus.

- ^ Smith, s.v. Sarpedon (1); Brill's New Pauly, s.v. Sarpedon (1); Hesiod, Catalogue of Women fr. 89 Most, pp. 172–5 [= fr. 140 Merkelbach-West, p. 68].

- ^ Homer, Odyssey 11.260–3; Brill's New Pauly s.v. Amphion; Grimal, s.v. Amphion, p. 38.

- ^ RE, s.v. Angelos 1; Sophron apud Scholia on Theocritus, Idylls 2.12.

- ^ Eleutheria is the Greek counterpart of Libertas (Liberty), daughter of Jove and Juno as cited in Hyginus, Fabulae Preface.

- ^ Parada, s.v. Eris, p. 72. Homer, Iliad 4.440–1 calls Eris the sister of Ares, who is the son of Zeus and Hera in the Iliad.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 79, 141; Gantz, p. 74; Homer, Iliad 1.577–9, 14.293–6, 14.338, Odyssey 8.312; Scholia bT on Homer's Iliad, 14.296.

- ^ Homer, Iliad 6.191–199; Hard 2004, p. 349; Smith, s.v. Sarpe'don (2).

- ^ Gantz, pp. 318–9. Helen is called the daughter of Zeus in Homer, Iliad 3.199, 3.418, 3.426, Odyssey 4.184, 4.219, 23.218, and she has the same mother (Leda) as Castor and Pollux in Iliad 3.236–8.

- ^ Cypria, fr. 10 West, pp. 88–91; Hard 2004, p. 438.

- ^ Gantz, p. 167; Hesiod, Catalogue of Women fr. 2 Most, pp. 42–5 [= fr. 5 Merkelbach-West, pp. 5–6 = Ioannes Lydus, De Mensibus 1.13].

- ^ Parada, s.vv. Hellen (1), p. 86, Pyrrha (1), p. 159; Apollodorus, 1.7.2; Hesiod, Catalogue of Women fr. 5 Most, pp. 46, 47 [= Scholia on Homer's Odyssey 10.2]; West 1985, pp. 51, 53, 56, 173, table 1.

- ^ Hesiod, Catalogue of Women fr. 7 Most, pp. 48, 49 [= Constantine Porphyrogenitus, De Thematibus, 2].

- ^ Pindar, Olympian 12.1–2; Gantz, p. 151.

- ^ Herodotus, Histories 4.5.1.

- ^ Stephanus of Byzantium, Ethnica s.v. Torrhēbos, citing Hellanicus and Nicolaus

- ^ Brill's New Pauly, s.v. Tityus; Hard 2004, pp. 147–148; FGrHist 3 F55 [= Scholia on Apollonius of Rhodes, 1.760–2b (Wendel, p. 65)].

- ^ Cicero, De Natura Deorum 3.59.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca historica 5.55.5

- ^ Dionysius of Halicarnassus, 5.48.1; Smith, s.v. Saon.

- ^ Cicero, De Natura Deorum 3.42.

- ^ Hyginus, Fabulae 155

- ^ Strabo, Geographica 10.3.19

- ^ Valerius Flaccus, Argonautica 6.48ff., 6.651ff

- ^ Hyginus Fabulae 82; Antoninus Liberalis, 36; Pausanias, 2.22.3; Gantz, p. 536; Hard 2004, p. 502.

- ^ Apollodorus, 3.12.6; Grimal, s.v. Asopus, p. 63; Smith, s.v. Asopus.

- ^ Apollodorus, 1.4.1; Hard 2004, p. 216.

- ^ Apollodorus, 3.8.2; Pausanias, 8.3.6; Hard 2004, p. 540; Gantz, pp. 725–726.

- ^ Brill's New Pauly, s.v. Calyce (1); Smith, s.v. Endymion; Apollodorus, 1.7.5.

- ^ Apollodorus, 2.1.1; Gantz, p. 198.

- ^ a b Apollodorus, 3.12.1; Hard 2004, 521.

- ^ Nonnus, Dionysiaca 3.195.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca historica 5.48.2.

- ^ Apollodorus, 3.12.6; Hard 2004, p. 530–531.

- ^ FGrHist 299 F5 [= Scholia on Pindar's Olympian 9.104a].

- ^ Pausanias, 2.30.3; March, s.v. Britomartis, p. 88; Smith, s.v. Britomartis.

- ^ Gantz, pp. 26, 40; Musaeus fr. 16 Diels, p. 183; Scholiast on Apollonius Rhodius, Argonautica 3.467

- ^ Cicero, De Natura Deorum 3.42; Athenaeus, Deipnosophists 9.392e (pp. 320, 321).

- ^ Stephanus of Byzantium, s.v. Akragantes; Smith, s.v. Acragas.

- ^ Scholiast on Pindar, Pythian Odes 3.177; Hesychius

- ^ FGrHist 1753 F1b.

- ^ Smith, s.v. Agdistis; Pausanias, 7.17.10. Agdistis springs from the earth in a place where Zeus's seed landed.

- ^ Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman Antiquities 1.27.1; Grimal, s.v. Manes, p. 271.

- ^ Nonnus, Dionysiaca 14.193.

- ^ Morand, p. 335; Orphic Hymn to Melinoë (71), 3–4 (Athanassakis and Wolkow, p. 57).

- ^ Grimal, s.v. Zagreus, p. 466; Nonnus, Dionysiaca 6.155.

- ^ Cicero, De Natura Deorum 3.21-23.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 46; Keightley, p. 55; Alcman fr. 57 Campbell, pp. 434, 435.

- ^ Cook 1914, p. 456; Smith, s.v. Selene.

- ^ Homeric Hymn to Selene (32), 15–16; Hyginus, Fabulae Preface; Hard 2004, p. 46; Grimal, s.v. Selene, p. 415.

- ^ Apollodorus, 1.1.3.

- ^ West 1983, p. 73; Orphic fr. 58 Kern [= Athenagoras, Legatio Pro Christianis 20.2]; Meisner, p. 134.

- ^ Smith, s.v. Thaleia (3); Oxford Classical Dictionary, s.v. Palici, p. 1100; Servius, On Aeneid, 9.581–4.

- ^ Grimal, s.v. Myrmidon, p. 299; Hard 2004, p. 533

- ^ Stephanus of Byzantium, s.v. Krētē.

- ^ Grimal, s.v. Epaphus; Apollodorus, 2.1.3.

- ^ Nonnus, Dionysiaca 32.70

- ^ Antoninus Liberalis, 13.

- ^ Pausanias, 3.1.2.

- ^ Brill's New Pauly, s.v. Themisto; Stephanus of Byzantium, s.v. Arkadia [= FGrHist 334 F75].

- ^ Pausanias, 1.40.1.

- ^ Stephanus of Byzantium, s.v. Ōlenos.

- ^ Stephanus of Byzantium, s.v. Pisidia; Grimal, s.v. Solymus, p. 424.

- ^ Smith, s.v. Orchomenus (3).

- ^ Smith, s.v. Agamedes.

- ^ Ptolemy Hephaestion apud Photius, Bibliotheca 190.47 (English translation).

- ^ Pausanias, 10.12.1; Smith, s.v. Lamia (1).

- ^ Eustathius ad Homer, p. 1688

- ^ Servius, Commentary on Virgil's Aeneid 1. 242

- ^ Apollodorus, 1.7.2; Pausanias, 5.1.3; Hyginus, Fabulae 155.

- ^ Hyginus, Fabulae 155.

- ^ Pindar, Olympian Ode 9.58.

- ^ a b Tzetzes on Lycophron, 1206 (pp. 957–962).[non-primary source needed]

- ^ John Lydus, De mensibus 4.67.

- ^ Homer, Iliad 19.91.

- ^ "Apollonius Rhodius, Argonautica, book 2, line 887". www.perseus.tufts.edu.

- ^ Orphic Hymn to Dionysus (30), 6–7 (Athanassakis and Wolkow, p. 27)

- ^ Homer, Iliad 9.502; Quintus Smyrnaeus, Posthomerica 10.301 (pp. 440, 441); Smith, s.v. Litae.

- ^ Valer. Flacc., Argonautica 5.205

- ^ Stephanus of Byzantium, Ethnica s.v. Tainaros

- ^ Pausanias, 2.1.1.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca historica 5.81.4

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 507-565

- ^ Hesiod, Works and Days 60–105.

- ^ Ovid, Metamorphoses 1.216–1.348

- ^ Leeming, David (2004). Flood | The Oxford Companion to World Mythology. Oxford University Press. p. 138. ISBN 9780195156690. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- ^ "The Gods in the Iliad". department.monm.edu. Archived from the original on 19 December 2015. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ^ Homer (1990). The Iliad. South Africa: Penguin Classics.

- ^ Hyginus, Fabulae 146.

- ^ Meisner, pp. 1, 5

- ^ West 1983, pp. 73–74; Meisner, p. 134; Orphic frr. 58 [= Athenagoras, Legatio Pro Christianis 20.2] 153 Kern.

- ^ Apollodorus, 3.76.

- ^ Apollodorus, 3.13.5.

- ^ Pindar, Isthmian odes 8.25

- ^ Apollodorus, 3.10.4

- ^ Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca historica 4.71.2

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 285

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 554; Apollodorus, Epitome 1.20

- ^ Ovid, Metamorphoses 1.747–2.400; Hyginus, De astronomia 2.42.2; Nonnus, Dionysiaca 38.142–435

- ^ Lucian, Dialogues of the Gods Zeus and the Sun

- ^ The bust below the base of the neck is eighteenth century. The head, which is roughly worked at back and must have occupied a niche, was found at Hadrian's Villa, Tivoli and donated to the British Museum by John Thomas Barber Beaumont in 1836. BM 1516. (British Museum, A Catalogue of Sculpture in the Department of Greek and Roman Antiquities, 1904).

- ^ Homer, Iliad 1.202, 2.157, 2.375; Pindar, Isthmian Odes 4.99; Hyginus, De astronomia 2.13.7.

- ^ Spanh. ad Callim. hymn. in Jov, 49

- ^ Schmitz, Leonhard (1867). "Aegiduchos". In Smith, William (ed.). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. Vol. I. Boston. p. 26. Archived from the original on 11 February 2009. Retrieved 19 October 2007.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Hanson, Victor Davis (18 December 2007). Carnage and Culture: Landmark Battles in the Rise to Western Power. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-42518-8.

- ^ LIMC, s.v. Zeus, p. 342.

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.; Johannes Hahn: Gewalt und religiöser Konflikt; The Holy Land and the Bible

- ^ Durant, The Life of Greece (The Story of Civilization Part II, New York: Simon & Schuster) 1939:23.

- ^ Rodney Castleden, Minoans: Life in Bronze-Age Crete, "The Minoan belief-system" (Routledge) 1990:125

- ^ Pointed out by Bernard Clive Dietrich, The Origins of Greek Religion (de Gruyter) 1973:15.

- ^ A.B. Cook, Zeus Cambridge University Press, 1914, I, figs 397, 398.

- ^ Dietrich 1973, noting Martin P. Nilsson, Minoan-Mycenaean Religion, and Its Survival in Greek Religion 1950:551 and notes.

- ^ "Professor Stylianos Alexiou reminds us that there were other divine boys who survived from the religion of the pre-Hellenic period — Linos, Ploutos and Dionysos — so not all the young male deities we see depicted in Minoan works of art are necessarily Velchanos" (Castleden) 1990:125