Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Prolonged labor

View on Wikipedia| Prolonged labor | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Failure to progress |

| |

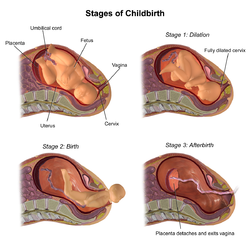

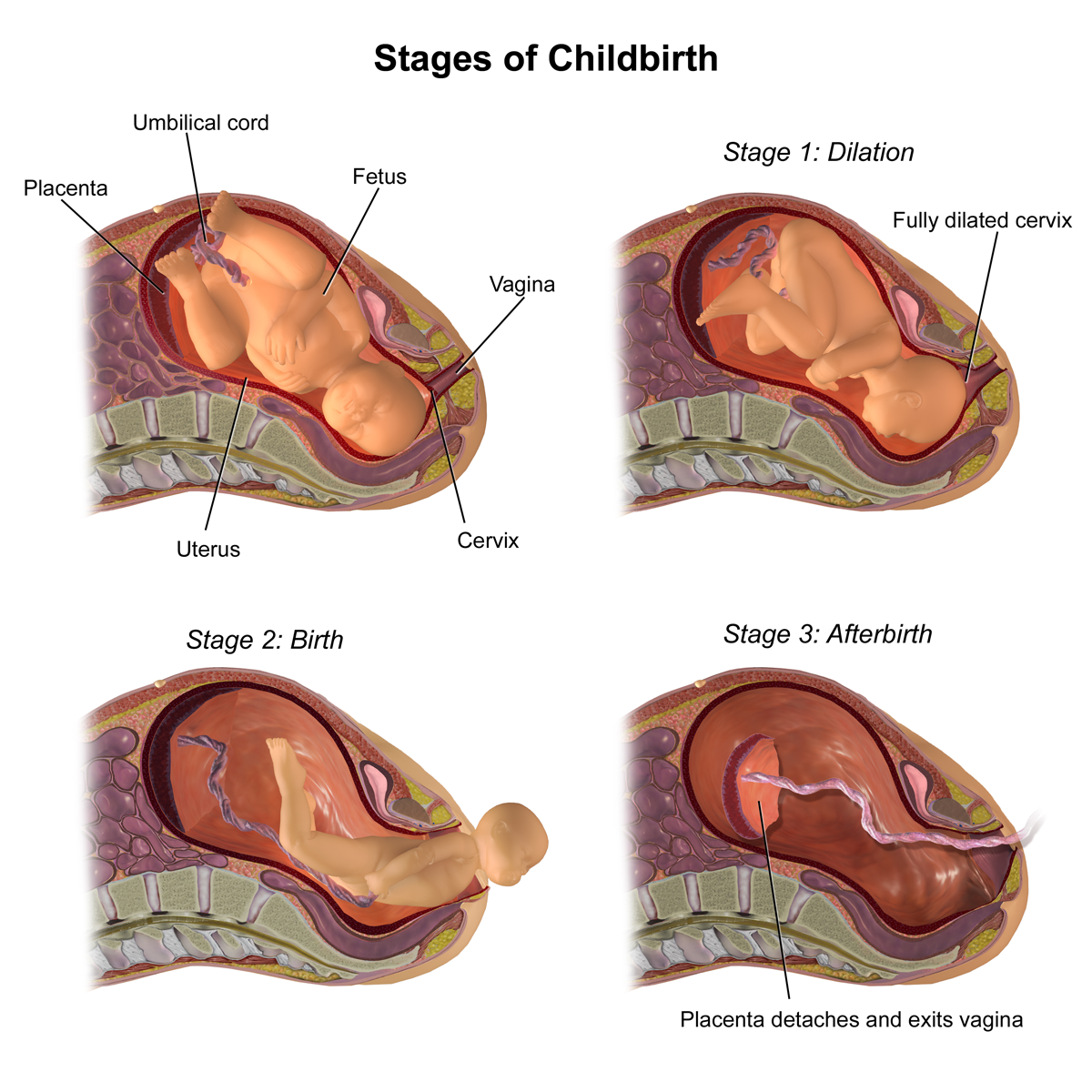

| Normal stages of childbirth | |

Prolonged labor is the inability of a woman to proceed with childbirth upon going into labor.[1] Prolonged labor typically lasts over 20 hours for first time mothers, and over 14 hours for women that have already had children.[1] Failure to progress can take place during two different phases; the latent phase and active phase of labor.[1] The latent phase of labor can be emotionally tiring and cause fatigue, but it typically does not result in further problems.[1] The active phase of labor, on the other hand, if prolonged, can result in long term complications.[1]

It is important that the vital signs of the woman and fetus are being monitored so preventive measures can be taken if prolonged labor begins. Women experiencing prolonged labor should be under supervision of a surgically equipped doctor. Prolonged labor is determined based on the information that is being collected regarding the strength and time between contractions. Medical teams track this data using intrauterine pressure catheter placement (IUPC) and continuous electronic fetal monitoring (EFM).[2] IUPC is a straw that is inserted into the womb with a monitor that reads when contractions are coming and how strong they are.[2] EFMs are used to track the fetal heart rate.[2] If either devices indicate that vital signs are off and prolonged labor is beginning, it is important that the medical team begin discussing treatment and alternative options for delivery.

Prolonged labor can result from a variety of different issues, such as fetal malpresentation, issues with uterine contractions, cervical dystocia or stenosis, and cephalopelvic disproportion. Both fetal malpresentation and cervical dystocia may result in obstructed labor.[3] The cause of prolonged labor will determine the medical intervention that needs to take place. Medical professionals can either engage in preventive measures or turn to surgical methods of removing the fetus. If not handled properly or immediately treated, both the woman and the fetus can suffer a variety of long term complications, the most serious of which is death.[4] There is no "quick fix" to prolonged labor, but there are preventive measures that can be taken, such as oxytocin infusions.[4] In order to properly and safely deliver the baby, doctors will often intervene in child birth and conduct assisted vaginal delivery through the use of forceps or a vacuum extractor, or perform a Caesarean section.[5]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Symptoms include:[6]

- Labor extends beyond 18 hours

- Dehydration and exhaustion of the mother

- Pain around the back, sides, and thighs of the mother as a result of extreme muscle pressure

- Severe pain when labor begins

- Increased heart rate of the mother

- Swollen large intestine on either side of the uterus as a result of gas build up

- Uterus sensitivity

- Ketosis

- Distress of the fetus

- Uterine ruptures

Complications

[edit]- Distress to the fetus as a result of decreasing oxygen levels

- Internal bleeding of the fetus's head (intracranial hemorrhage)

- Higher chance of operative delivery

- Risks of long-term injuries to the infant such as hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) or cerebral palsy

- Infection of the uterus

- Damage to the birth canal

- Postpartum infection

- Postpartum hemorrhage

Prolonged latent labor

[edit]The term describes labor that occurs very slowly.[2] This does not necessarily mean that the woman or fetus's health is being compromised, but it is painful and is an important indication for doctors to pay attention to warning signs of prolonged labor.[2]

Prolonged active labor

[edit]The phase of labor that extends into multiple hours (at least 14). The cervix usually dilates to over 4 cm before active labor occurs.[7] When it first begins, it is encouraged that women stand up, walk around, and eat or drink.[8] If failure to progress extends beyond this point, preventive measures need to be taken.

Causes

[edit]Fetal malpresentations

[edit]Fetal malpresentations are irregular positions of the crown of the fetal head in relation to the mother's pelvis (the fetus is in an abnormal position).[9] Some important ways to manage fetal malpresentation are making rapid evaluations of the condition of the women pertaining to vital signs as well as the heart rate of the fetus.[9] If fetal heart rate is abnormal, and if membranes have ruptured and amniotic fluid is atypical, it is important for medical professionals to determine the presenting part of the fetus and the position of the fetal head.[9] Possible delivery methods, if this is the case, are compound presentation, vaginal breech delivery, or caesarean section for breech presentation depending upon the severity of the malposition.[9]

Uterine contractions

[edit]This refers to uterine conditions that result in the uterus not having enough coordination or strength to dilate the cervix and push the baby through the birth canal. Issues with uterine contractions are the main cause of prolonged labor during the latent phase. Contractions may not occur as of a result of uterine tumors. In addition, if the uterus is stretched, usually due to previous pregnancies or multiple gestation, contractions may be difficult. Irregular or weak contractions can be fixed through stimulation of the uterus or oxytocin infusions. Lack of contractions may be caused by an overwhelming amount of painkillers or anesthesia, by which the medications should be discontinued. In this case, it is appropriate for assisted vaginal delivery to be conducted.

Cervical stenosis

[edit]Cervical dystocia, or stenosis, occurs when the cervix fails to dilate after a practical amount of time during positive uterine pains. The main problems in cervical dystocia is the lack of uterine inertia and cervical abnormalities, which prevent the cervix from fully dilating.[10] It is very typical of patients that have hypopituitarism.[11] There are many preexisting complications that may result in stenosis. Common conditions that lead to stenosis are tumors, a full bladder, large size of the infant, multiple pregnancies, delay in rupture of membranes, or problems with the cervix.[11] High stress may interfere with the progression of pregnancy in cases such as these, leading to prolonged labor.[11]

Cephalopelvic disproportion

[edit]Cephalopelvic disproportion is the issue that arises when the fetus' body or head is too large to pass through the woman’s pelvis.[12] Common conditions that lead to CPD are diabetes, multiple pregnancies, small or abnormally shaped pelvis, atypical fetal positions, hereditary factors, and first time pregnancies.[12] Medical professionals can usually estimate if fetal size is too large based on ultrasounds, but they are not always entirely accurate.[12] Doctors typically determine CPD when labor begins and the use of oxytocin is not effective. The safest way for delivery to take place when CPD is a factor is through Caesarean sections.[12]

Prevention

[edit]If the woman is being closely monitored and begins to show signs of prolonged labor, medical professionals can take preventive measures to better the chances of delivery within 24 hours.[4] A precise initial diagnosis of prolonged labor based on signs and symptoms is extremely important in applying proper precautionary treatment.[4] Oxytocin infusions upon an initial amniotomy is typically used to move normal labor back on track.[4] The application of oxytocin is only effective if administered on the basis of fetal distress.[4] This treatment method only pertains to specific states of the fetus. If the baby is experiencing malpresentation, for example, the only safe and reliable method to proceed with childbirth is medical interference.[4]

Management

[edit]In terms of medical care, preventive treatment or assisted delivery are typically the first options doctors consider. There is usually no quick fix to prolonged labor, especially if preventive measures do not revert the mother back to normal labor. Often, medical professionals resort to intervention methods. If the state of the fetus and mother are not especially serious or threatening to their health, doctors will perform assisted vaginal deliveries.

Assisted vaginal delivery

[edit]There are two different methods of assisted vaginal delivery that medical professionals typically utilize to aid in delivery in order to avoid surgical methods of fetal extraction. These procedures are only applied if a vaginal delivery has proven to still be safe to the woman and the baby, based on their vital signs. Assisted vaginal delivery is usually only used in the latent phase.[5] Delivery during the active phase is usually associated with more complications for the woman.[5] One approach to assisted vaginal delivery is the use of forceps.[5] The forceps doctors use resemble two large salad spoons and are inserted into the cervix, around the baby's head and help to guide it out of the birth canal.[5] The other option is the use of vacuum extraction. Vacuums used have a cup on the end and are inserted into the cervix.[5] The cup attaches to the fetus's head by suction and aids in guiding delivery. The choice between forceps and vacuum extraction is usually made by the doctor based on preference. It is important that these methods are used properly, or else they can cause severe birth injuries to the baby that may be permanent.[5]

Caesarean sections

[edit]Caesarean sections, also referred to as C-sections, are usually quick solutions to the issue of failure to progress. Often, C-sections are the best options to avoid harming the fetus or the woman, especially if labor proves to be life-threatening. One third of C-sections occur as a result of prolonged labor.[1] C-sections are usually a necessary measure in prolonged labor to avoid serious birth complications. If the mother reaches the active phase of prolonged labor, a C-section is the safest solution. Caesarean sections need to be performed immediately if there are signs of fetal distress, uterine rupture, or cord prolapse. It is important that medical professionals are equipped and prepared in the case of an imperative C-section. There is a window of time by which Caesarean sections need to be executed if any warning signs present themselves. If there is a delay in the C-section, permanent damage can result to the baby, such as cerebral palsy or hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE). Due to all the risk factors that are present in the event of prolonged labor, it is extremely important that medical teams are well-suited and prepared to conduct a C-section if needed.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f "Prolonged Labor: Failure to Progress - Causes and Solutions". American Pregnancy Association. 2014-08-15. Retrieved 2018-12-07.

- ^ a b c d e "Prolonged Labor: Causes and Treatment". WebMD. Retrieved 2018-12-07.

- ^ Education material for teachers of midwifery : midwifery education modules. Geneva [Switzerland]: World Health Organization. 2008. pp. 17–36. ISBN 9789241546669.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gallagher, John T.; Jackson, Reginald J. A.; O'Driscoll, Kieran (1969-05-24). "Prevention of Prolonged Labour". Br Med J. 2 (5655): 477–480. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.5655.477. ISSN 1468-5833. PMC 1983378. PMID 5771578.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Procedures That May Take Place During Labor and Delivery". pennmedicine.adam.com. Retrieved 2018-12-08.

- ^ "Prolonged Labor can occur due to cpd, malpresentations, uterine inertia etc". Gynaeonline. Retrieved 2018-10-25.

- ^ "Protracted Labor - Gynecology and Obstetrics". Merck Manuals Professional Edition. Retrieved 2018-12-08.

- ^ Nystedt, Astrid; Hildingsson, Ingegerd (2014-07-16). "Diverse definitions of prolonged labour and its consequences with sometimes subsequent inappropriate treatment". BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 14 (1): 233. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-14-233. ISSN 1471-2393. PMC 4105110. PMID 25031035.

- ^ a b c d "MCPC - Malpositions and malpresentations - Health Education To Villages". hetv.org. Retrieved 2018-12-06.

- ^ Arthur, Hugh R. (1949-12-01). "Cervical Dystocia". BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 56 (6): 983–993. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1949.tb07164.x. ISSN 1471-0528. PMID 15410101. S2CID 40011612.

- ^ a b c Arnot, Philip H. (January 1952). "PROLONGED LABOR". California Medicine. 76 (1): 20–22. ISSN 0008-1264. PMC 1521210. PMID 14886755.

- ^ a b c d "Cephalopelvic Disproportion (CPD): Causes and Diagnosis". American Pregnancy Association. 2012-04-26. Retrieved 2018-12-06.

External links

[edit]Prolonged labor

View on GrokipediaDefinition and epidemiology

Definition

Prolonged labor, also known as labor dystocia, is defined as abnormally slow or arrested progress of labor that deviates from expected durations, primarily affecting the first stage of labor (cervical dilation) or the second stage (fetal descent).[1][4] This condition encompasses difficult or obstructed labor, characterized by inadequate cervical dilation or fetal descent during active labor, often requiring intervention to prevent maternal or fetal complications.[4] Labor is classified into the latent phase (from onset to approximately 6 cm cervical dilation) and the active phase (from 6 cm to full 10 cm dilation). In the latent phase, progress is gradual, with prolongation defined as exceeding 20 hours in nulliparous women or 14 hours in multiparous women, though contemporary assessments consider the 95th percentile thresholds around 16 hours for nulliparous individuals.[1] The active phase expects a minimum dilation rate of 1 cm per hour, but evaluations now use 95th percentile benchmarks rather than rigid minima to account for variability.[1] Traditional criteria, based on Emanuel Friedman's 1950s labor curve—a sigmoid-shaped graph depicting strict timelines such as active phase onset at 4 cm dilation and arrest after 2 hours without progress—have largely been supplanted by modern standards like the Zhang curve. Derived from large contemporary datasets, the Zhang curve follows a hyperbolic pattern, indicating more variable and lenient progress: the median active phase duration is approximately 5.5 hours from 4 to 10 cm, with 95% of nulliparous women completing within 6 to 18 hours and multiparous women faster thereafter, without a deceleration phase.[1][5] The World Health Organization defines prolonged labor as the onset of regular contractions with cervical dilation lasting more than 24 hours without progress.[6] The term "dystocia" originates from the Greek dustokía, meaning "difficult childbirth," and provides a conceptual framework through the "4 Ps": powers (uterine contractions and maternal efforts), passenger (fetal size, position, and presentation), passage (maternal pelvic anatomy), and psyche (psychological factors influencing labor).[7][8]Epidemiology

Prolonged labor affects approximately 8-15% of births worldwide, with rates varying based on definitions and monitoring capabilities.[2] In high-resource settings, the incidence is typically around 8-10%, while rates are often higher in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) due to factors such as limited access to timely interventions and higher prevalence of malnutrition-related pelvic disproportion.[9] The prevalence of a prolonged latent phase, defined as exceeding 20 hours in nulliparous women or 14 hours in multiparous women, is estimated at 5-6.5% of labors. In the United States, recent studies report about 9% of second-stage labors as prolonged.[10][11] Prevalence estimates vary due to inconsistent definitions of prolonged labor across international guidelines and studies.[12] Demographic patterns show prolonged labor is three to five times more common in nulliparous women compared to multiparous women, with odds ratios ranging from 3.3 to 4.8. Maternal obesity (BMI >30 kg/m²) increases the risk by 1.5-2 times, primarily through extended labor durations and higher dystocia rates. Advanced maternal age over 35 years is associated with approximately 25-30% incidence in nulliparous women, linked to increased cesarean needs and labor complications.[2][13][14] Prolonged labor accounts for 30-50% of primary cesarean sections in high-income countries, where it remains the leading indication for intrapartum cesareans. Adoption of updated guidelines, such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) 2024 endorsement of the Zhang labor curve—which extends active phase thresholds to 6 cm dilation—has reduced dystocia diagnoses by 20-40% in some cohorts, contributing to declining overall rates.[1][12][15]Diagnosis

Clinical features

Prolonged labor manifests through distinct maternal and fetal signs that indicate stalled progression during childbirth. Maternal indicators include persistent, painful uterine contractions that fail to advance cervical dilation or fetal descent, often leading to significant physical and emotional strain. Women commonly experience profound fatigue and exhaustion from the extended duration of labor, compounded by dehydration evidenced by dry mucous membranes and reduced urine output. Back pain is frequently reported, particularly in the lower back, due to the prolonged positioning and strain on the maternal body.[16][17][18] In the first stage of labor, contractions may be prolonged in duration, lasting over 60 seconds, yet occur infrequently, with fewer than three contractions in every 10 minutes, contributing to the lack of cervical progress. During the second stage, despite maternal pushing efforts, there is a notable absence of fetal descent through the birth canal, further exacerbating maternal distress. Associated symptoms often include heightened anxiety and an inability to rest between contractions, as the ongoing pain and uncertainty intensify psychological burden. Signs suggestive of infection, such as maternal fever exceeding 38°C or foul-smelling vaginal discharge, may emerge if labor extends significantly, signaling potential chorioamnionitis.[16][18][17] Fetal signs of distress become evident through abnormal heart rate patterns, including recurrent decelerations that reflect compromised oxygenation. If the amniotic membranes rupture during prolonged labor, meconium-stained fluid may be observed, indicating fetal stress and passage of the first stool in utero.[16][17][18] These features differentiate prolonged labor from normal labor, where gradual cervical dilation consistent with contemporary labor curves—such as slower progression (medians often below 1 cm per hour early in the active phase) per the Zhang curve—accompanies consistent fetal descent and reassuring vital signs, without the plateau or regression in progress seen in dystocia.[16][18][1]Diagnostic criteria

The diagnosis of prolonged labor relies on standardized tools and thresholds to identify deviations from normal labor progression, ensuring timely intervention while minimizing unnecessary cesarean deliveries. The World Health Organization (WHO) partograph remains a cornerstone for monitoring, serving as a graphical tool that plots cervical dilation, contraction frequency and intensity, fetal heart rate, and maternal vital signs against time from the onset of active labor. The alert line, drawn at a rate of 1 cm per hour starting from 4 cm dilation, indicates potential delay if labor crosses it; the action line, positioned 4 hours to the right of the alert line, signals the need for expedited evaluation and management, such as augmentation or transfer to a higher-level facility.[19][20] Contemporary criteria, informed by contemporary labor curve analyses, have shifted away from rigid historical timelines like the Friedman curve toward more flexible, evidence-based thresholds. The Zhang labor curve, derived from large-scale observational data on over 5,000 nulliparous women, defines active phase arrest as no cervical change after 4 hours of adequate uterine activity or 6 hours of oxytocin augmentation, after reaching 6 cm dilation. For the second stage, prolongation is diagnosed after more than 3 hours of pushing in nulliparous women or 2 hours in multiparous women, with consideration for epidural use in individualized assessment. These criteria emphasize allowing labor to progress beyond traditional limits before diagnosing arrest, reducing operative interventions.[21] The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline aligns with these contemporary approaches, designating the inflection to active labor at 6 cm cervical dilation rather than earlier thresholds, and diagnosing arrest only after rupture of membranes, an adequate trial of oxytocin if contractions are inadequate, and subsequent lack of progress. This guideline explicitly discourages reliance on outdated Friedman curve timelines, which often overestimate arrest and contribute to rising cesarean rates, prioritizing individualized assessment over fixed durations.[1] In addition to progression tracking, confirmatory assessments include serial pelvic examinations to evaluate cervical effacement, fetal station, and head position; transabdominal or transperineal ultrasound to detect malposition or malpresentation that may impede descent; and continuous electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) to identify category II or III tracings indicating potential fetal distress, which could compound or mimic prolonged labor.[22][18] Differential diagnosis is essential to distinguish true prolonged labor from non-progressive patterns, such as false labor characterized by irregular, non-dilating contractions without cervical change, or the contrasting precipitous labor, defined as delivery within 3 hours of regular contractions, which requires rapid management to avoid complications like perineal trauma.[23][24]Causes and risk factors

Fetal factors

Fetal factors contributing to prolonged labor primarily involve characteristics of the fetus that impede its descent and rotation through the birth canal, often categorized under the "passenger" in the classic 4 Ps framework of labor dynamics. These include malpresentations, excessive fetal size, structural anomalies, multiple gestations, and certain placental abnormalities that indirectly affect labor progression by compromising uterine efficiency or fetal positioning. Malpresentations, where the fetus is not in the optimal occiput anterior position, are a leading fetal cause of prolonged labor. Occiput posterior position occurs in approximately 20-30% of labors during the active phase and is associated with extended labor duration, typically by 1-2 hours in the second stage compared to occiput anterior presentations, due to deflexion of the fetal head and inefficient cervical dilation. Breech and transverse lie presentations further complicate descent, increasing the risk of labor arrest and necessitating interventions like cesarean delivery. These malpresentations are diagnosed through abdominal palpation via Leopold maneuvers or intrapartum ultrasound, which can confirm position and guide management. Fetal macrosomia, defined as birth weight exceeding 4500 grams, significantly elevates the risk of prolonged labor, primarily through mechanisms such as shoulder dystocia or head entrapment after delivery of the body. This condition often arises in association with maternal gestational diabetes, which promotes excessive fetal growth. Macrosomia leads to cephalopelvic disproportion, prolonging the second stage of labor and heightening the likelihood of operative delivery. Congenital anomalies that enlarge the fetal head, such as hydrocephalus or tumors, can cause mechanical obstruction during labor. Hydrocephalus, characterized by ventricular enlargement due to cerebrospinal fluid accumulation, results in a biparietal diameter that may exceed normal limits, leading to protracted labor if the head circumference surpasses 35 cm. Such anomalies contribute to cephalopelvic disproportion, often requiring cesarean section to avoid fetal distress. Multiple gestations, including twins or higher-order multiples, are linked to irregular uterine contractions and persistent malposition, thereby extending labor duration. In twin pregnancies, the second stage is frequently prolonged due to the need for sequential delivery and potential interlocking of fetal heads or malpresentation of the second twin, increasing risks of maternal exhaustion and fetal compromise. Placental issues like abruption or previa can indirectly prolong labor by reducing placental perfusion and uterine contractility, leading to inefficient contractions and fetal maladaptation. Abruption, involving premature separation of the placenta, may cause hypertonus or pain that disrupts normal labor progression, while previa's low implantation can limit cervical changes and precipitate bleeding that halts vaginal delivery attempts.Maternal factors

Maternal factors contributing to prolonged labor primarily involve anatomical and physiological characteristics of the mother's pelvis, uterus, and cervix that impede the normal progression of labor, often categorized under the "passage" element in the classic framework of labor dynamics. These factors can lead to dystocia by hindering cervical dilation, uterine contractions, or fetal descent through the birth canal. Key contributors include cephalopelvic disproportion, obesity, advanced maternal age, uterine abnormalities, and cervical issues, each altering the efficiency of labor mechanics. Cephalopelvic disproportion (CPD) arises from a mismatch between the size or shape of the fetal head and the maternal pelvis, preventing adequate descent and rotation during labor. This condition is particularly associated with certain pelvic types, such as the android pelvis, which features a narrow, heart-shaped inlet that restricts fetal passage. A contracted pelvic inlet, typically measuring less than 10 cm in transverse diameter, further exacerbates the risk by limiting space for fetal accommodation. Maternal short stature, defined as height under 150 cm, independently elevates the likelihood of CPD by approximately twofold, as shorter stature correlates with smaller pelvic dimensions. Additionally, a history of previous cesarean delivery increases CPD risk due to potential pelvic scarring or unrecognized prior disproportion, often necessitating surgical intervention in subsequent labors.[25][26][27] Obesity, characterized by a pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) greater than 30 kg/m², is linked to a 1.5- to 2-fold higher incidence of prolonged labor compared to normal-weight women. This association stems from reduced myometrial contractility, resulting in inefficient uterine contractions that fail to generate sufficient force for cervical dilation and fetal expulsion. Obese women also experience higher rates of epidural analgesia use, which can prolong the second stage of labor by diminishing the urge to push and altering pain-mediated reflexes. These physiological changes collectively extend labor duration, increasing the need for augmentation or operative delivery.[28][29] Advanced maternal age, particularly over 35 years, elevates the risk of prolonged labor by 20% to 30%, primarily through diminished myometrial efficiency. Aging alters the expression of contractile proteins in uterine smooth muscle, leading to weaker and less coordinated contractions that slow labor progression. Studies indicate that women in this age group exhibit reduced oxytocin receptor responsiveness, further impairing uterine responsiveness during active labor. This age-related decline contributes to higher rates of labor dystocia, often requiring interventions like oxytocin infusion.[30][29] Uterine abnormalities, such as fibroids (leiomyomas) or scars from prior surgeries like myomectomy, can distort the endometrial cavity and disrupt normal labor dynamics. Submucosal or intramural fibroids greater than 5 cm in size mechanically interfere with uterine contraction patterns, leading to irregular or inadequate force generation that prolongs the first stage of labor. Previous myomectomy, while beneficial for fertility, may leave adhesions or weaken the uterine wall if the cavity is breached, potentially causing cavity distortion and impeding fetal descent. These structural changes heighten the risk of dystocia.[31][32] Cervical factors, including stenosis or scarring from prior procedures such as loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) or cone biopsy, directly impair dilation and contribute to prolonged labor. Scar tissue reduces cervical elasticity, physically resisting effacement and opening, which can arrest progress in the latent phase. This leads to slow or stalled dilation, often below 1 cm per hour, increasing the overall labor duration and risk of maternal exhaustion. Women with such histories may require manual dilation or cesarean delivery to avoid complications like infection.[29][33]Other factors

Inadequate uterine contractions, often termed hypotonic uterine dysfunction, represent a primary dynamic contributor to prolonged labor, characterized by weak or infrequent contractions that fail to generate sufficient propulsive force for cervical dilation and fetal descent. This condition arises from uterine inertia, where contractions exhibit reduced intensity, typically below 200 Montevideo units (MVU), a measure of uterine contractility assessed via intrauterine pressure monitoring. Hypotonic dysfunction is the most common cause of first-stage labor dystocia and accounts for a substantial proportion of prolonged labor cases, frequently occurring after labor induction due to overstimulation or exhaustion of uterine muscle fibers.[34][35][36] Psychological factors, encapsulated as the "psyche" in the classic four Ps of labor (power, passenger, passage, and psyche), can further impede progress by influencing maternal physiology and behavior. Maternal fear, anxiety, or uncooperativeness activates the sympathetic nervous system, releasing stress hormones that inhibit oxytocin release and contribute to dysfunctional uterine contractility, often extending the latent phase of labor. Studies indicate that heightened anxiety correlates with longer overall labor durations, potentially by 1-3 hours in the early stages, through mechanisms such as reduced cooperation with contractions or altered pain perception.[17][37][38] Iatrogenic factors, stemming from medical interventions, also play a significant role in prolonging labor by disrupting natural dynamics. Epidural analgesia, while effective for pain relief, commonly extends the second stage by reducing maternal pushing efforts and blunting proprioceptive feedback, with research showing up to a fivefold increase in the odds of a prolonged second stage compared to non-epidural labors. Similarly, inducing labor without prior cervical ripening in an unfavorable cervix heightens the risk of protracted active phase due to inefficient contraction patterns, often necessitating augmentation. Dehydration during labor, if unmanaged, diminishes contraction strength by reducing blood volume and uterine perfusion, leading to hypotonic patterns that delay progression.[39][40][41] Cervical dystocia contributes to prolonged labor through non-anatomical barriers to dilation, such as a rigid cervical ring or edematous tissue that resists effacement. This condition manifests as failure of the cervix to dilate despite adequate contractions, often presenting as a palpable cartilaginous ring at the external os or persistent anterior lip edema, distinct from fixed anatomical stenosis. It typically arises from prolonged pressure or inflammation during labor, impeding the transition to the active phase without structural pelvic abnormalities.[42][43] Abnormalities in amniotic fluid volume, including polyhydramnios and oligohydramnios, alter intrauterine pressure dynamics and can precipitate prolonged labor. Polyhydramnios, an excess of fluid, overdistends the uterus, potentially weakening contraction efficiency and increasing the risk of a protracted first stage by disrupting the transmission of forces to the cervix. Conversely, oligohydramnios reduces fluid cushioning, which may compress the umbilical cord or limit fetal mobility, contributing to dysfunctional labor patterns, particularly in post-term gestations where low fluid exacerbates uterine inertia.[44][45][46]Complications

Maternal complications

Prolonged labor significantly elevates the risk of maternal morbidity, encompassing acute infections, excessive bleeding, physical trauma, metabolic disturbances, and enduring pelvic floor issues. These complications arise primarily from extended exposure to labor stresses, such as prolonged membrane rupture, frequent vaginal examinations, and uterine fatigue, which compromise maternal homeostasis and tissue integrity.[16][47] Infection represents a primary concern, with chorioamnionitis—characterized by maternal fever and uterine tenderness—occurring in 3-13% of term deliveries, with risk increasing with prolonged labor and rupture of membranes due to ascending bacterial invasion following membrane rupture.[48][49] Postpartum endometritis, an inflammation of the uterine lining, further complicates recovery, with odds increasing alongside prolonged second-stage labor as bacterial contamination persists.[50] Incidence rates for these infections are higher in unmanaged prolonged cases, up to 10% or more depending on duration, particularly when internal monitoring or interventions prolong exposure.[51] Hemorrhage, especially postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) from uterine atony, is markedly heightened, with labor exceeding 12 hours in the active phase associating with severe blood loss often surpassing 500 mL. Women experiencing labor ≥24 hours face approximately 3.4 times greater likelihood of PPH compared to shorter durations, attributable to uterine exhaustion impairing contraction efficacy.[52][53] Trauma to maternal tissues is frequent, including severe perineal lacerations (third- or fourth-degree) with incidence up to 10% of vaginal deliveries, higher in cases involving instrumental delivery often necessitated by stalled progress in prolonged labor. In low-resource settings, obstructed prolonged labor contributes to vesicovaginal fistulas in 1-2% of affected women, resulting from pressure necrosis between the bladder and vagina, with global estimates indicating 30,000-130,000 new cases annually.[54][47][55] Maternal exhaustion and metabolic derangements manifest as dehydration and electrolyte imbalances from extended fasting and fluid loss, potentially progressing to ketoacidosis in severe instances. These factors compound fatigue, often necessitating cesarean delivery, a leading indication for operative intervention to resolve arrest.[56][57] Long-term sequelae include chronic pelvic pain and urinary incontinence, affecting a significant proportion of women post-prolonged second-stage labor due to sustained pelvic floor strain and potential levator ani injury, with increased odds compared to shorter labors. These disorders, encompassing stress incontinence and prolapse, persist beyond the puerperium, diminishing quality of life and necessitating ongoing management.[58][59]Fetal and neonatal complications

Prolonged labor increases the risk of fetal hypoxia, which can lead to metabolic acidosis characterized by an umbilical artery pH below 7.20.[60] This acidosis arises from sustained oxygen deprivation during extended uterine contractions and reduced placental perfusion, potentially compromising fetal well-being.[61] Neonates born after a prolonged second stage of labor, exceeding 4 hours, face a higher likelihood of low 5-minute Apgar scores below 7, indicating immediate postnatal distress.[62] Such hypoxic events during labor are associated with an elevated risk of cerebral palsy, though CP is multifactorial, with studies showing increased odds from prolonged labor-related complications.[63][64] Prolonged rupture of membranes beyond 18 hours heightens the risk of neonatal sepsis due to ascending bacterial infection, with risk increasing to around 5% or higher in affected cases.[65] Pathogens such as group B Streptococcus can colonize the amniotic fluid, leading to early-onset sepsis in the newborn, often presenting with respiratory distress, lethargy, and elevated inflammatory markers.[66] Birth trauma is a significant concern in prolonged labor, particularly when operative interventions like forceps are employed to expedite delivery. Brachial plexus injuries, including Erb's palsy, occur at rates of 0.5-2 per 1,000 live births, resulting from excessive traction on the fetal neck and shoulder during extraction.[67] Skull fractures and intracranial hemorrhages may also arise from instrumental assistance or cephalopelvic disproportion, with fractures typically linear and hemorrhages ranging from subdural to subarachnoid types, potentially causing neurological deficits.[68][69] Respiratory complications include meconium aspiration syndrome (MAS), especially in post-term pregnancies complicated by prolonged labor, where the incidence reaches approximately 5% among those with meconium-stained amniotic fluid.[70] Fetal distress prompts meconium passage, and inhalation during gasping respirations leads to airway obstruction, inflammation, and possible persistent pulmonary hypertension. Long-term neurodevelopmental delays are linked to the hypoxic and traumatic insults of prolonged labor, with affected children showing increased risks of conditions such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Operative deliveries, often necessitated by labor prolongation, correlate with higher ADHD odds, potentially due to subtle brain injuries or stress responses during birth.[71][72] These outcomes underscore the importance of vigilant monitoring to mitigate enduring impacts on cognitive and behavioral development.Prevention

Antenatal strategies

Antenatal strategies for preventing prolonged labor focus on identifying and mitigating risk factors before delivery to optimize labor progression. Risk screening begins with routine clinical assessments tailored to high-risk populations, such as women of short stature, where pelvic measurements like the diagonal conjugate can predict cephalopelvic disproportion (CPD); a diagonal conjugate less than 11.5 cm may indicate the need for closer monitoring or alternative delivery planning. Additionally, ultrasound estimation of fetal weight is recommended in suspected cases of macrosomia, with fetuses estimated at over 5000 grams in non-diabetic mothers or 4500 grams in diabetic mothers flagged for potential cesarean discussion to avoid dystocia.[73] These screenings help stratify risks early, allowing for personalized antenatal care plans, including identification of factors like nulliparity and obesity, with emphasis on shared decision-making. Lifestyle interventions play a key role in reducing modifiable risk factors associated with prolonged labor, particularly obesity and gestational diabetes. For obese pregnant women (BMI ≥30 kg/m²), guidelines recommend limiting gestational weight gain to 5-9 kg (11-20 lbs) through balanced diet and moderate exercise, which correlates with lower rates of fetal macrosomia and subsequent labor dystocia. Similarly, tight control of gestational diabetes through dietary management, monitoring, and insulin if needed can reduce the incidence of macrosomia, thereby decreasing the likelihood of prolonged first-stage labor. These measures emphasize preconception and early pregnancy counseling to promote healthier outcomes. Education and preparation during antenatal visits empower women to support efficient labor. Antenatal classes that teach optimal labor positions, such as upright postures and movement, have been shown to shorten labor duration by facilitating fetal descent and cervical dilation. Preparation also includes assessing cervical readiness via the Bishop score for women considering induction, where a score below 6 indicates the potential need for ripening agents to prevent failed induction and prolonged labor. Such education fosters informed decision-making and reduces anxiety-related delays in labor progress. Medical interventions in the antenatal period target underlying conditions that could prolong labor. Elective induction of labor is advised against before 39 weeks in low-risk pregnancies, as it increases the risk of prolonged labor and cesarean delivery without clear benefits. For women with symptomatic uterine fibroids, myomectomy or other treatments may be considered preconceptionally or early in pregnancy to alleviate potential obstruction during labor. For high-risk cases, such as known CPD or breech presentation, antenatal planning includes discussions on elective cesarean section to circumvent prolonged labor risks. In breech presentations diagnosed via ultrasound after 36 weeks, external cephalic version or planned cesarean is often recommended, with cesarean reducing the odds of prolonged labor and associated complications. Similarly, a history of CPD prompts multidisciplinary counseling on delivery mode, prioritizing maternal and fetal safety. These strategies integrate seamlessly with overall prenatal care to minimize the incidence of prolonged labor.Intrapartum strategies

Intrapartum strategies for preventing prolonged labor emphasize proactive monitoring and supportive interventions during active labor to promote progress and detect deviations early, thereby reducing the need for more invasive measures. The World Health Organization (WHO) Labour Care Guide (LCG), introduced in 2020 as an evolution of the traditional partograph, serves as a key tool for this purpose by integrating woman-centered assessments of progress, fetal well-being, and maternal status. Unlike the partograph's strict alert and action lines based on cervical dilatation rates, the LCG uses flexible progress thresholds—such as alert if no progress after 6 hours at 5 cm, 5 hours at 6 cm, 3 hours at 7 cm, 2.5 hours at 8 cm, or 2 hours at 9 cm—to identify potential delays without over-relying on time-based criteria alone.[74] Continuous use of the LCG allows healthcare providers to detect early deviations in labor progress, with recommendations for plotting cervical dilatation, fetal heart rate, contractions, and maternal vital signs at regular intervals. Fetal heart rate monitoring via intermittent auscultation is advised every 30 minutes during the first stage and every 5 minutes in the second stage for low-risk pregnancies, enabling timely identification of abnormalities like tachycardia or bradycardia that could contribute to labor stagnation.[75] Supportive care plays a crucial role in maintaining labor efficiency by addressing physiological factors that may impede progress. Adequate hydration is essential, with oral fluids encouraged for low-risk women to sustain energy and prevent dehydration-related uterine hypotonia; if oral intake is insufficient, intravenous fluids should be administered to maintain urine output above 30 mL/hour, as oliguria below this threshold signals inadequate hydration and potential labor prolongation. Encouraging ambulation and upright positions, such as walking or kneeling, during the first stage of labor has been shown to shorten its duration by approximately 1 hour and reduce the cesarean section rate by about 25% compared to supine positioning, likely due to enhanced gravitational effects on fetal descent and stronger contractions.[1] Non-pharmacologic interventions further support labor advancement by minimizing discomfort and promoting natural progress without routine medicalization. Continuous emotional and physical support from a doula or companion of choice is recommended throughout labor, as it is associated with shorter labor durations, lower rates of cesarean delivery (by up to 39%), and reduced use of interventions like oxytocin augmentation. Hydrotherapy, including immersion in warm water or showers, can alleviate pain and facilitate mobility, and may be associated with decreased duration of the first stage in some studies, along with decreased epidural requests, without increasing risks to mother or baby. Routine episiotomy should be avoided, as it does not prevent labor prolongation and may increase perineal trauma; instead, it is reserved for specific indications like fetal distress. Epidural analgesia is recommended based on patient preference; while it may prolong the second stage of labor due to motor blockade, it does not increase the duration of the first stage.[76] Early intervention thresholds guide judicious use of augmentation to avert prolongation without unnecessary risks. Amniotomy (artificial rupture of membranes) should only be considered if there is no cervical progress after reaching 6 cm dilatation in the active phase, as routine early use does not reliably shorten labor and may heighten infection risks; when performed, it typically reduces the first stage by about 1 hour in selected cases.[76] For mild augmentation in early deviations, nipple stimulation can be offered as a non-invasive option in appropriate contexts, such as for cervical ripening, to stimulate endogenous oxytocin release and enhance contractions. In low-resource settings, transfer protocols are vital for timely escalation when preventive measures indicate risk. If the LCG reveals crossing of alert thresholds—such as labor exceeding expected progress intervals or abnormal fetal heart patterns—immediate referral to a higher-level facility is recommended, ideally within 1-2 hours, to access advanced care and prevent complications from untreated prolongation.[75] This approach, integrated into routine intrapartum monitoring, has been shown to reduce maternal and perinatal morbidity in resource-limited environments by facilitating early intervention.[77]Management

Non-surgical management

Non-surgical management of prolonged labor focuses on conservative and medical interventions aimed at promoting cervical dilation, uterine contractions, and fetal descent without resorting to operative delivery. These approaches prioritize maternal hydration, augmentation of contractions, and supportive measures to facilitate progress while minimizing risks such as infection or fetal distress. Initial assessments, including contraction patterns, guide these interventions to address underlying causes like inadequate uterine activity or dehydration.[1] Hydration is a foundational step to correct potential dehydration, which can contribute to diminished uterine contractions and prolonged labor. Intravenous fluids are typically administered at rates of 125-250 mL per hour of isotonic crystalloid solution, such as lactated Ringer's, to maintain maternal volume status and support labor progression. Studies have shown that higher rates, like 250 mL/h, can reduce cesarean delivery rates and shorten labor duration compared to 125 mL/h by optimizing maternal physiology. Additionally, short rest periods of 1-2 hours may be recommended during the latent phase to allow maternal recovery, reduce fatigue, and potentially enhance subsequent contraction efficiency, particularly in cases of early exhaustion.[78][79][17] Oxytocin augmentation is commonly used to stimulate uterine contractions when labor stalls due to hypotonic dysfunction. Infusion typically begins at 0.5-2 mU/min intravenously, with incremental increases of 1-2 mU/min every 30 minutes until adequate contractions are achieved, up to a maximum of 20-40 mU/min, while monitoring for hyperstimulation. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) endorses both low-dose (starting at 0.5-1 mU/min, increasing by 1-2 mU/min every 30-40 minutes) and high-dose (starting at 2-4 mU/min, increasing by 2-4 mU/min every 15-30 minutes) protocols, as both effectively shorten labor duration by 2-4 hours without significant differences in maternal or neonatal outcomes. Continuous electronic fetal monitoring is essential during augmentation to ensure fetal well-being.[80][1][81] Amniotomy, or artificial rupture of membranes, may be performed if the fetal head is engaged in the pelvis to accelerate the active phase of labor by increasing endogenous prostaglandin release and contraction intensity. This intervention can shorten the active phase by approximately 1-2 hours in nulliparous women, potentially reducing overall labor time. However, it carries risks, including an elevated chance of chorioamnionitis if performed prematurely or if labor prolongs further, necessitating careful timing and sterile technique. ACOG guidelines advise against routine use in uncomplicated labors but support it selectively for augmentation.[1][82][83] Maternal position changes are encouraged to optimize pelvic dimensions and fetal alignment, particularly in cases of occiput posterior presentation. The hands-and-knees or knee-chest position can facilitate rotation to occiput anterior, improving descent and reducing labor duration. In the second stage, use of a peanut ball—a peanut-shaped birthing ball placed between the legs in lateral or semi-Fowler positions—has been shown to shorten this phase by 20-30 minutes by widening the pelvic outlet and enhancing maternal comfort. These non-pharmacologic techniques are low-risk and can be integrated with other supports like ambulation.[84][85][86] Pain relief options must be judiciously selected to avoid impeding progress, as certain analgesics can prolong labor stages. Limited epidural analgesia, such as combined spinal-epidural with low-dose local anesthetics, provides effective relief without excessive motor blockade that might hinder pushing. Systemic opioids like fentanyl or remifentanil may be used sparingly for breakthrough pain, offering rapid onset but shorter duration to minimize respiratory depression in the neonate. ACOG emphasizes individualized approaches, noting that while neuraxial techniques are gold standard for pain control, they may extend the second stage by up to 1 hour, warranting close monitoring.[87][88][89]Surgical management

Surgical management of prolonged labor is indicated when non-surgical interventions, such as oxytocin augmentation, fail to achieve adequate progress, aiming to expedite delivery and mitigate risks of maternal and fetal compromise. Operative approaches include assisted vaginal delivery and cesarean section, selected based on fetal station, maternal pelvic adequacy, and clinical urgency. These interventions are guided by established protocols to balance efficacy with minimizing complications.[1] Assisted vaginal delivery is often attempted in the second stage of labor when there is arrest of descent, provided the fetal head is at an appropriate station and rotation is feasible. Vacuum extraction is suitable for fetal stations of +2 cm or higher, with success rates typically ranging from 80% to 95% in appropriately selected cases, particularly when used for prolonged second stage without fetal distress.30149-6/fulltext)[90] Forceps-assisted delivery is preferred for low or outlet applications, especially in scenarios of fetal distress or when vacuum fails, offering a success rate of around 90% in skilled hands.[91] Both methods carry risks of maternal perineal or vaginal lacerations, occurring in approximately 13-25% of cases depending on the instrument used, with forceps associated with higher rates than vacuum.[92] A trial of operative vaginal delivery is recommended before proceeding to cesarean if prerequisites are met, as it reduces the need for more invasive surgery.[1] Cesarean section is warranted for active phase arrest of labor, defined as no cervical change after at least 4 hours of adequate uterine contractions or 6 hours of oxytocin augmentation in the presence of ruptured membranes and dilation of 6 cm or more.[1] It is also indicated emergently for fetal distress or failure to progress despite augmentation. Labor dystocia, encompassing prolonged labor, is the leading indication for primary cesarean delivery, accounting for up to 50% of such procedures in some cohorts.[18] In the second stage, operative intervention is considered after more than 3 hours in nulliparous women or 2 hours in multiparous women without fetal descent, despite epidural analgesia and pushing efforts.[1] Postoperative care following surgical delivery focuses on infection prevention and hemorrhage surveillance. For cases complicated by chorioamnionitis, broad-spectrum antibiotics such as ampicillin and gentamicin are continued, with an additional dose administered at cord clamping during cesarean to cover intraamniotic infection.[93] Vital signs and uterine tone are monitored closely to detect postpartum hemorrhage, with routine thromboprophylaxis considered based on risk factors.00071-7/abstract) Surgical interventions effectively reduce fetal hypoxia risks associated with prolonged labor but are linked to increased maternal recovery demands, including hospital stays of 3 to 4 days post-cesarean compared to vaginal delivery. Operative vaginal births generally confer lower maternal morbidity than unplanned cesareans performed in advanced labor.[94][1]References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/dystocia