Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Fetus

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Human growth and development |

|---|

|

| Stages |

| Biological milestones |

| Development and psychology |

A fetus or foetus (/ˈfiːtəs/; pl.: fetuses, foetuses, rarely feti or foeti) is the unborn offspring of a viviparous animal that develops from an embryo.[1] Following the embryonic stage, the fetal stage of development takes place. Prenatal development is a continuum, with no clear defining feature distinguishing an embryo from a fetus. However, in general a fetus is characterized by the presence of all the major body organs, though they will not yet be fully developed and functional, and some may not yet be situated in their final anatomical location.

In human prenatal development, fetal development begins from the ninth week after fertilization (which is the eleventh week of gestational age) and continues until the birth of a newborn.

Etymology

[edit]The word fetus (plural fetuses or rarely, the solecism feti[2]) comes from Latin fētus 'offspring, bringing forth, hatching of young'.[3][4][5] The Latin plural fetūs is not used in English; occasionally the plural feti is used in English by analogy with second-declension Latin nouns.[2]

The predominant British, Irish, and Commonwealth spelling is foetus, except in medical usage, where fetus is preferred. The -oe- spelling is first attested in 1594 and arose in Late Latin by analogy with classical Latin words like amoenus.[6]

Non-human animals

[edit]

A fetus is a stage in the prenatal development of viviparous organisms. This stage lies between embryogenesis and birth.[1] Many vertebrates have fetal stages, ranging from most mammals to many fish. In addition, some invertebrates bear live young, including some species of onychophora[7] and many arthropods.

The fetuses of most mammals are situated similarly to the human fetus within their mothers.[8] However, the anatomy of the area surrounding a fetus is different in litter-bearing animals compared to humans: each fetus of a litter-bearing animal is surrounded by placental tissue and is lodged along one of two long uteri instead of the single uterus found in a human female.

Development at birth varies considerably among animals, and even among mammals. Altricial species are relatively helpless at birth and require considerable parental care and protection. In contrast, precocial animals are born with open eyes, have hair or down, have large brains, and are immediately mobile and somewhat able to flee from, or defend themselves against, predators. Primates are precocial at birth, with the exception of humans.[9]

The duration of gestation in placental mammals varies from 18 days in jumping mice to 23 months in elephants.[10] Generally speaking, fetuses of larger land mammals require longer gestation periods.[10]

The benefits of a fetal stage means that young are more developed when they are born. Therefore, they may need less parental care and may be better able to fend for themselves. However, carrying fetuses exerts costs on the mother, who must take on extra food to fuel the growth of her offspring, and whose mobility and comfort may be affected (especially toward the end of the fetal stage).

In some instances, the presence of a fetal stage may allow organisms to time the birth of their offspring to a favorable season.[7]

Development in humans

[edit]Weeks 9 to 16 (2 to 3.6 months)

[edit]

In humans, the fetal stage starts nine weeks after fertilization.[11] At this time the fetus is typically about 30 millimetres (1+1⁄4 in) in length from crown to rump, and weighs about 8 grams.[11] The head makes up nearly half of the size of the fetus.[12] Breathing-like movements of the fetus are necessary for the stimulation of lung development, rather than for obtaining oxygen.[13] The heart, hands, feet, brain, and other organs are present, but are only at the beginning of development and have minimal operation.[14][15] Uncontrolled movements and twitches occur as muscles, the brain, and pathways begin to develop.[16]

Weeks 17 to 25 (3.6 to 6.6 months)

[edit]A woman pregnant for the first time (nulliparous) typically feels fetal movements at about 21 weeks, whereas a woman who has given birth before will typically feel movements by 20 weeks.[17] By the end of the fifth month, the fetus is about 20 cm (8 in) long.

Weeks 26 to 38 (6.6 to 8.6 months)

[edit]The amount of body fat rapidly increases. Lungs are not fully mature. Neural connections between the sensory cortex and thalamus develop as early as 24 weeks of gestational age, but the first evidence of their function does not occur until around 30 weeks.[citation needed] Bones are fully developed but are still soft and pliable. Iron, calcium, and phosphorus become more abundant. Fingernails reach the end of the fingertips. The lanugo, or fine hair, begins to disappear until it is gone except on the upper arms and shoulders. Small breast buds are present in both sexes. Head hair becomes coarse and thicker. Birth is imminent and occurs around the 38th week after fertilization. The fetus is considered full-term between weeks 37 and 40 when it is sufficiently developed for life outside the uterus.[18][19] It may be 48 to 53 cm (19 to 21 in) in length when born. Control of movement is limited at birth, and purposeful voluntary movements continue to develop until puberty.[20][21]

Variation in growth

[edit]There is much variation in the growth of the human fetus. When the fetal size is less than expected, the condition is known as intrauterine growth restriction also called fetal growth restriction; factors affecting fetal growth can be maternal, placental, or fetal.[22]

- Maternal factors include maternal weight, body mass index, nutritional state, emotional stress, toxin exposure (including tobacco, alcohol, heroin, and other drugs which can also harm the fetus in other ways), and uterine blood flow.

- Placental factors include size, microstructure (densities and architecture), umbilical blood flow, transporters and binding proteins, nutrient utilization, and nutrient production.

- Fetal factors include the fetal genome, nutrient production, and hormone output. Also, female fetuses tend to weigh less than males, at full term.[22]

Fetal growth is often classified as follows: small for gestational age (SGA), appropriate for gestational age (AGA), and large for gestational age (LGA).[23] SGA can result in low birth weight, although premature birth can also result in low birth weight. Low birth weight increases the risk for perinatal mortality (death shortly after birth), asphyxia, hypothermia, polycythemia, hypocalcemia, immune dysfunction, neurologic abnormalities, and other long-term health problems. SGA may be associated with growth delay, or it may instead be associated with absolute stunting of growth.

Viability

[edit]Fetal viability refers to a point in fetal development at which the fetus may survive outside the womb. The lower limit of viability is approximately 5+3⁄4 months gestational age and is usually later.[24]

There is no sharp limit of development, age, or weight at which a fetus automatically becomes viable.[25] According to data from 2003 to 2005, survival rates are 20–35% for babies born at 23 weeks of gestation (5+3⁄4 months); 50–70% at 24–25 weeks (6 – 6+1⁄4 months); and >90% at 26–27 weeks (6+1⁄2 – 6+3⁄4 months) and over.[26] It is rare for a baby weighing less than 500 g (1 lb 2 oz) to survive.[25]

When such premature babies are born, the main causes of mortality are that neither the respiratory system nor the central nervous system are completely differentiated. If given expert postnatal care, some preterm babies weighing less than 500 g (1 lb 2 oz) may survive, and are referred to as extremely low birth weight or immature infants.[25]

Preterm birth is the most common cause of infant mortality, causing almost 30 percent of neonatal deaths.[26] At an occurrence rate of 5% to 18% of all deliveries,[27] it is also more common than postmature birth, which occurs in 3% to 12% of pregnancies.[28]

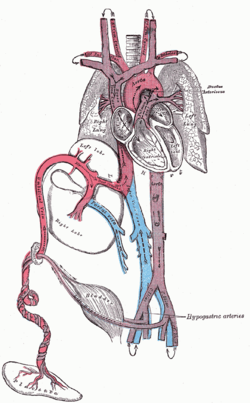

Circulatory system

[edit]Before birth

[edit]

The heart and blood vessels of the circulatory system form relatively early during embryonic development, but continue to grow and develop in complexity in the growing fetus. A functional circulatory system is a biological necessity since mammalian tissues can not grow more than a few cell layers thick without an active blood supply. The prenatal circulation of blood is different from postnatal circulation, mainly because the lungs are not in use. The fetus obtains oxygen and nutrients from the mother through the placenta and the umbilical cord.[29]

Blood from the placenta is carried to the fetus by the umbilical vein. About half of this enters the fetal ductus venosus and is carried to the inferior vena cava, while the other half enters the liver proper from the inferior border of the liver. The branch of the umbilical vein that supplies the right lobe of the liver first joins with the portal vein. The blood then moves to the right atrium of the heart. In the fetus, there is an opening between the right and left atrium (the foramen ovale), and most of the blood flows from the right into the left atrium, thus bypassing pulmonary circulation. The majority of blood flow is into the left ventricle from where it is pumped through the aorta into the body. Some of the blood moves from the aorta through the internal iliac arteries to the umbilical arteries and re-enters the placenta, where carbon dioxide and other waste products from the fetus are taken up and enter the mother's circulation.[29]

Some of the blood from the right atrium does not enter the left atrium, but enters the right ventricle and is pumped into the pulmonary artery. In the fetus, there is a special connection between the pulmonary artery and the aorta, called the ductus arteriosus, which directs most of this blood away from the lungs (which are not being used for respiration at this point as the fetus is suspended in amniotic fluid).[29]

-

Fetus at 4+1⁄4 months

-

Fetus at 5 months

Postnatal development

[edit]With the first breath after birth, the system changes suddenly. Pulmonary resistance is reduced dramatically, prompting more blood to move into the pulmonary arteries from the right atrium and ventricle of the heart and less to flow through the foramen ovale into the left atrium. The blood from the lungs travels through the pulmonary veins to the left atrium, producing an increase in pressure that pushes the septum primum against the septum secundum, closing the foramen ovale and completing the separation of the newborn's circulatory system into the standard left and right sides. Thereafter, the foramen ovale is known as the fossa ovalis.

The ductus arteriosus normally closes within one or two days of birth, leaving the ligamentum arteriosum, while the umbilical vein and ductus venosus usually closes within two to five days after birth, leaving, respectively, the liver's ligamentum teres and ligamentum venosus.

Immune system

[edit]The placenta functions as a maternal-fetal barrier against the transmission of microbes. When this is insufficient, mother-to-child transmission of infectious diseases can occur.

Maternal IgG antibodies cross the placenta, giving the fetus passive immunity against those diseases for which the mother has antibodies. This transfer of antibodies in humans begins as early as the fifth month (gestational age) and certainly by the sixth month.[30]

Developmental problems

[edit]A developing fetus is highly susceptible to anomalies in its growth and metabolism, increasing the risk of birth defects. One area of concern is the lifestyle choices made during pregnancy.[31] Diet is especially important in the early stages of development. Studies show that supplementation of the person's diet with folic acid reduces the risk of spina bifida and other neural tube defects. Another dietary concern is whether breakfast is eaten. Skipping breakfast could lead to extended periods of lower than normal nutrients in the maternal blood, leading to a higher risk of prematurity, or birth defects.

Alcohol consumption may increase the risk of the development of fetal alcohol syndrome, a condition leading to intellectual disability in some infants.[32] Smoking during pregnancy may also lead to miscarriages and low birth weight (2,500 grams (5 pounds 8 ounces). Low birth weight is a concern for medical providers due to the tendency of these infants, described as "premature by weight", to have a higher risk of secondary medical problems.

X-rays are known to have possible adverse effects on the development of the fetus, and the risks need to be weighed against the benefits.[33][34]

Congenital disorders are acquired before birth. Infants with certain congenital heart defects can survive only as long as the ductus remains open: in such cases the closure of the ductus can be delayed by the administration of prostaglandins to permit sufficient time for the surgical correction of the anomalies. Conversely, in cases of patent ductus arteriosus, where the ductus does not properly close, drugs that inhibit prostaglandin synthesis can be used to encourage its closure, so that surgery can be avoided.

Other heart birth defects include ventricular septal defect, pulmonary atresia, and tetralogy of Fallot.

An abdominal pregnancy can result in the death of the fetus and where this is rarely not resolved it can lead to its formation into a lithopedion.

Fetal pain

[edit]The existence and implications of fetal pain are debated politically and academically. According to the conclusions of a review published in 2005, "Evidence regarding the capacity for fetal pain is limited but indicates that fetal perception of pain is unlikely before the third trimester."[35][36] However, developmental neurobiologists argue that the establishment of thalamocortical connections (at about 6+1⁄2 months) is an essential event with regard to fetal perception of pain.[37][page needed] Nevertheless, the perception of pain involves sensory, emotional and cognitive factors and it is "impossible to know" when pain is experienced, even if it is known when thalamocortical connections are established.[37] Some authors argue that fetal pain is possible from the second half of pregnancy. Evidence suggests that the perception of pain in the fetus occurs well before late gestation.[38]

Whether a fetus has the ability to feel pain and suffering is part of the abortion debate.[39][40][41] In the United States, for example, anti-abortion advocates have proposed legislation that would require providers of abortions to tell pregnant women that their fetuses will feel pain during the procedure and that would require each person to accept or decline anesthesia for the fetus.[42]

Legal and social issues

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2022) |

Abortion of a human pregnancy is legal and/or tolerated in most countries, although with gestational time limits that normally prohibit late-term abortions.[43]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Ghosh, Shampa; Raghunath, Manchala; Sinha, Jitendra Kumar (2017), "Fetus", Encyclopedia of Animal Cognition and Behavior, Springer International Publishing, pp. 1–5, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-47829-6_62-1, ISBN 9783319478296

- ^ a b Oxford English Dictionary, 2013, s.v. 'fetus'

- ^ O.E.D.2nd Ed.2005

- ^ Harper, Douglas. (2001). Online Etymology Dictionary Archived 2013-04-20 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2007-01-20.

- ^ "Charlton T. Lewis, An Elementary Latin Dictionary, fētus". Archived from the original on 2017-01-04. Retrieved 2015-09-24.

- ^ New Oxford Dictionary of English.

- ^ a b Campiglia, Sylvia S.; Walker, Muriel H. (1995). "Developing embryo and cyclic changes in the uterus of Peripatus (Macroperipatus) acacioi (Onychophora, Peripatidae)". Journal of Morphology. 224 (2): 179–198. Bibcode:1995JMorp.224..179C. doi:10.1002/jmor.1052240207. PMID 29865325. S2CID 46928727.

- ^ ZFIN, Pharyngula Period (24–48 h) Archived 2007-07-14 at the Wayback Machine. Modified from: Kimmel et al., 1995. Developmental Dynamics 203:253–310. Downloaded 5 March 2007.

- ^ Lewin, Roger. Human Evolution Archived 2023-04-07 at the Wayback Machine, page 78 (Blackwell 2004).

- ^ a b Sumich, James and Dudley, Gordon. Laboratory and Field Investigations in Marine Life, page 320 (Jones & Bartlett 2008).

- ^ a b Klossner, N. Jayne, Introductory Maternity Nursing (2005): "The fetal stage is from the beginning of the 9th week after fertilization and continues until birth"

- ^ "Fetal development: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". www.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2011-10-27.

- ^ Institute of Medicine of the National Academies, Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences, and Prevention Archived 2011-06-07 at the Wayback Machine (2006), page 317. Retrieved 2008-03-12

- ^ The Columbia Encyclopedia Archived 2007-10-12 at the Wayback Machine (Sixth Edition). Retrieved 2007-03-05.

- ^ Greenfield, Marjorie. "Dr. Spock.com Archived 2007-01-22 at the Wayback Machine". Retrieved 2007-01-20.

- ^ Prechtl, Heinz. "Prenatal and Early Postnatal Development of Human Motor Behavior" in Handbook of brain and behaviour in human development, Kalverboer and Gramsbergen eds., pp. 415–418 (2001 Kluwer Academic Publishers): "The first movements to occur are sideward bendings of the head. ... At 9–10 weeks postmestrual age complex and generalized movements occur. These are the so-called general movements (Prechtl et al., 1979) and the startles. Both include the whole body, but the general movements are slower and have a complex sequence of involved body parts, while the startle is a quick, phasic movement of all limbs and trunk and neck."

- ^ Levene, Malcolm et al. Essentials of Neonatal Medicine Archived 2023-04-08 at the Wayback Machine (Blackwell 2000), p. 8. Retrieved 2007-03-04.

- ^ "You and your baby at 37 weeks pregnant". NHS.UK. 8 December 2020. Archived from the original on 2022-11-02. Retrieved 2022-11-01.

- ^ "Giving Birth Before Your Due Date: Do All 40 Weeks Matter?". Parents. Archived from the original on 2022-11-02. Retrieved 2022-11-01.

- ^ Stanley, Fiona et al. "Cerebral Palsies: Epidemiology and Causal Pathways", page 48 (2000 Cambridge University Press): "Motor competence at birth is limited in the human neonate. The voluntary control of movement develops and matures during a prolonged period up to puberty...."

- ^ Becher, Julie-Claire. "Insights into Early Fetal Development". Archived from the original on 2013-06-01., Behind the Medical Headlines (Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh and Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow October 2004)

- ^ a b Holden, Chris and MacDonald, Anita. Nutrition and Child Health Archived 2020-07-31 at the Wayback Machine (Elsevier 2000). Retrieved 2007-03-04.

- ^ Queenan, John. Management of High-Risk Pregnancy Archived 2023-04-24 at the Wayback Machine (Blackwell 1999). Retrieved 2007-03-04.

- ^ Halamek, Louis. "Prenatal Consultation at the Limits of Viability Archived 2009-06-08 at the Wayback Machine", NeoReviews, Vol.4 No.6 (2003): "most neonatologists would agree that survival of infants younger than approximately 22 to 23 weeks' estimated gestational age [i.e. 20 to 21 weeks' estimated fertilization age] is universally dismal and that resuscitative efforts should not be undertaken when a neonate is born at this point in pregnancy."

- ^ a b c Moore, Keith and Persaud, T. The Developing Human: Clinically Oriented Embryology, p. 103 (Saunders 2003).

- ^ a b March of Dimes – Neonatal Death Archived 2014-10-24 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved September 2, 2009.

- ^ World Health Organization (November 2014). "Preterm birth Fact sheet N°363". who.int. Archived from the original on 7 March 2015. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ^ Buck, Germaine M.; Platt, Robert W. (2011). Reproductive and perinatal epidemiology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 163. ISBN 9780199857746. Archived from the original on 2016-08-15.

- ^ a b c Whitaker, Kent (2001). Comprehensive Perinatal and Pediatric Respiratory Care. Delmar. Retrieved 2007-03-04.

- ^ Page 202 of Pillitteri, Adele (2009). Maternal and Child Health Nursing: Care of the Childbearing and Childrearing Family. Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-1-58255-999-5.

- ^ Dalby, JT (1978). "Environmental effects on prenatal development". Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 3 (3): 105–109. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/3.3.105.

- ^ Streissguth, Ann Pytkowicz (1997). Fetal alcohol syndrome: a guide for families and communities. Baltimore, MD: Paul H Brookes Pub. ISBN 978-1-55766-283-5.

- ^ O'Reilly, Deirdre. "Fetal development ". MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia (2007-10-19). Retrieved 2018-08-26.

- ^ De Santis, M; Cesari, E; Nobili, E; Straface, G; Cavaliere, AF; Caruso, A (September 2007). "Radiation effects on development". Birth Defects Research Part C: Embryo Today: Reviews. 81 (3): 177–82. doi:10.1002/bdrc.20099. PMID 17963274.

- ^ Lee, Susan; Ralston, HJ; Drey, EA; Partridge, JC; Rosen, MA (August 24–31, 2005). "Fetal Pain A Systematic Multidisciplinary Review of the Evidence". Journal of the American Medical Association. 294 (8): 947–54. doi:10.1001/jama.294.8.947. PMID 16118385. Two authors of the study published in JAMA did not report their abortion-related activities, which pro-life groups called a conflict of interest; the editor of JAMA responded that JAMA probably would have mentioned those activities if they had been disclosed, but still would have published the study. See Denise Grady, "Study Authors Didn't Report Abortion Ties" Archived 2009-04-25 at the Wayback Machine, New York Times (2005-08-26).

- ^ "Study: Fetus feels no pain until third trimester" NBC News

- ^ a b Johnson, Martin and Everitt, Barry. Essential reproduction (Blackwell 2000): "The multidimensionality of pain perception, involving sensory, emotional, and cognitive factors may in itself be the basis of conscious, painful experience, but it will remain difficult to attribute this to a fetus at any particular developmental age." Retrieved 2007-02-21.

- ^ "Fetal pain?". International Association for the Study of Pain. June 2006. Archived from the original on 2013-07-01.

- ^ "Unborn babies can feel pain". Minnesota Citizens Concerned for Life. Archived from the original on 2016-07-19.

The neural pathways are present for pain to be experienced quite early by unborn babies," explains Steven Calvin, M.D., perinatologist, chair of the Program in Human Rights Medicine, University of Minnesota, where he teaches obstetrics.

- ^ White, R. Frank (October 2001). "Are We Overlooking Fetal Pain and Suffering During Abortion?". American Society of Anesthesiologists Newsletter. 65. Archived from the original on Jan 25, 2008. Retrieved 2007-03-10.

- ^ David, Barry and Goldberg, Barth. "Recovering Damages for Fetal Pain and Suffering Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine", Illinois Bar Journal (December 2002). Retrieved 2007-03-10.

- ^ Weisman, Jonathan. "House to Consider Abortion Anesthesia Bill Archived 2008-10-28 at the Wayback Machine", Washington Post 2006-12-05. Retrieved 2007-02-06.

- ^ Anika Rahman, Laura Katzive and Stanley K. Henshaw. "A Global Review of Laws on Induced Abortion, 1985–1997 Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine", International Family Planning Perspectives Volume 24, Number 2 (June 1998).

External links

[edit]- Prenatal Image Gallery Index at the Endowment for Human Development website, featuring numerous motion pictures of human fetal movement.

- In the Womb (National Geographic video).

- Fetal development: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia

Fetus

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Terminology

Biological Definition

In developmental biology, the fetus is defined as the unborn offspring of a viviparous mammal during the postembryonic phase of prenatal development, following the establishment of the basic body plan in the embryonic stage.[9] This stage is characterized by the presence of all major organ rudiments, with subsequent emphasis on cellular proliferation, tissue differentiation, organ maturation, and physiological refinement rather than initial organogenesis.[10] The term applies across mammalian species, including humans, canines, and bovines, distinguishing the fetus from earlier developmental forms like the zygote, blastocyst, or embryo.[2] In humans, the fetal period begins at the start of the ninth week post-fertilization (equivalent to approximately the end of the eighth week or the conclusion of Carnegie stage 23), when the embryo transitions to a form with recognizable human features such as a large head, limb buds, and early sensory structures.[9] [1] This timing marks the shift from high-risk organ formation—prone to teratogenic disruptions—to a phase dominated by growth, where the organism increases in size from roughly 30 mm crown-rump length to an average of 50 cm at term, while developing coordinated functions like heartbeat (detectable from week 6 but strengthening thereafter) and rudimentary neural activity.[4] [10] The duration extends until parturition, typically 38-40 weeks post-fertilization, during which viability outside the uterus becomes possible after about 24 weeks due to advancements in lung surfactant production and central nervous system integration.[11] Biologically, the fetus remains dependent on placental exchange for nutrients, oxygen, and waste removal, underscoring its status as a distinct developmental entity within the maternal system.[3]Etymology and Historical Usage

The term fetus entered the English language in the late 14th century, borrowed directly from Latin fētus, which denoted "offspring," "bringing forth," or "hatching of young," encompassing both the process of gestation and the developing progeny.[12] This Latin noun traces to the Proto-Indo-European root dhe(i)-, signifying "to suck" or "to nurse," reflecting an association with the nourishment of young in the womb or egg, akin to derivations in Sanskrit dhitih ("nurse, lactation") and dhiyam ("milk").[12] In classical Latin usage, fētus broadly applied to viviparous offspring during pregnancy, sometimes extending figuratively to newborns, without the modern embryological precision distinguishing it from earlier developmental stages.[13] Historically, the word appeared in Middle English texts around 1350–1400, initially referring to the unborn young of viviparous animals, including humans, as an "act of bearing young" or the resultant entity.[14] In Roman medical and legal contexts, such as those preserved in works by authors like Pliny the Elder, fētus described the gestating form in discussions of reproduction and abortion, emphasizing its status as progeny rather than a mere biological process.[13] A variant spelling, foetus, emerged in the late 16th century (first attested 1594) through erroneous Late Latin influence from diphthong patterns in words like foedus, but the original fetus form predominates in etymologically accurate and contemporary medical nomenclature, with foetus now largely obsolete outside certain non-medical British conventions.[15] This evolution underscores the term's shift from a general descriptor of parturition to a specific stage of prenatal development post-organogenesis, formalized in 19th-century embryology.[14]Comparative Embryology and Development

Fetal Stage in Mammals

The fetal stage in placental mammals follows the embryonic period, commencing after gastrulation and the establishment of the basic body plan, including the formation of germ layers and major organ primordia. At this point, the developing organism transitions from primarily organogenesis to phases dominated by cellular proliferation, tissue expansion, and physiological maturation, resulting in an anatomically recognizable form with a distinct head, trunk, limbs, and tail. This stage is marked by the presence of all essential organ systems in rudimentary but functional states, supported by extraembryonic membranes such as the chorion (forming the fetal component of the placenta), amnion (enclosing the fetus in protective fluid), and yolk sac (initially aiding nutrient absorption).[16][17] Key characteristics of the fetal stage include rapid somatic growth, deposition of adipose tissue, ossification of skeletal elements, and development of integumentary features like hair follicles, claws, and pigmentation. Sensory and motor capabilities emerge, such as coordinated movements and responses to stimuli, while internal systems like the cardiovascular, respiratory, and nervous structures refine their connectivity and efficiency. The placenta, derived from trophoblast invasion of the uterine wall, facilitates maternal-fetal exchange of gases, nutrients, and wastes without direct blood mixing, enabling prolonged intrauterine development. In contrast to the embryonic stage's focus on cellular differentiation and vulnerability to teratogens during organ formation, the fetal period emphasizes quantitative growth and adaptive responses to maternal physiology.[16][18] The duration and specific milestones of the fetal stage vary across mammalian species, correlating with adult body size, metabolic rate, and reproductive strategy. In canines, it spans approximately days 35 to 61 of gestation, featuring eyelid fusion, hair growth, and sexual differentiation. Rodent models, such as mice, exhibit a compressed fetal phase post-implantation (around embryonic day 8-12 onward), culminating in birth at 19-21 days, with emphasis on neural circuit formation and thermoregulatory preparation. Larger mammals, like elephants, extend this stage over 18-22 months, prioritizing extensive brain growth and skeletal robustification. Marsupials, with abbreviated uterine phases, exhibit a brief fetal-like period before pouch migration, where fetal membranes play a limited role compared to placental counterparts. These differences underscore evolutionary adaptations in viviparity, where fetal viability hinges on placental efficiency and maternal resource allocation.[18][16]Distinctions from Embryonic Stage

The embryonic stage of human prenatal development encompasses the period from approximately the third week after fertilization (or the end of the second week post-fertilization) through the eighth week of gestation, during which rapid cell differentiation and organogenesis predominate, establishing the foundational body plan including the neural tube, heart, limbs, and major organ systems.[19] In contrast, the fetal stage commences at the ninth week of gestation and extends until birth, shifting emphasis from primary structure formation to substantial increases in size, weight, and functional maturation of pre-formed organs, with the fetus achieving a distinctly human-like appearance by this transition.[3] [20] A primary distinction lies in the developmental priorities: organogenesis, the process of organ formation, is largely completed by the end of the eighth week, rendering the embryo highly susceptible to environmental teratogens that can induce structural malformations, whereas the fetal phase involves refinement and histological specialization of organs alongside exponential growth, reducing the incidence of major congenital anomalies after this point.[19] [21] For instance, during the embryonic stage, exposure to agents like thalidomide primarily affects limb bud development due to ongoing mesenchymal differentiation, while fetal exposures more often result in functional deficits or growth restriction rather than gross structural defects.[22] Morphologically, the embryo exhibits transient features such as pharyngeal arches resembling gill slits, a prominent tail-like caudal eminence, and disproportionate body segments, which regress or transform by the fetal onset; the fetus, by week 9, measures about 3 cm crown-rump length with elongated limbs, a rounded head, and external genitalia beginning to differentiate, marking a departure from the C-shaped embryonic curvature toward proportional human form.[19] Physiologically, embryonic circulation relies on yolk sac and primitive placental support with yolk sac hematopoiesis, evolving into fetal hepatic and bone marrow erythropoiesis by weeks 6-8, after which fetal circulation features advanced shunts like the ductus venosus for hepatic bypass, supporting sustained growth demands.[23] The embryonic period's brevity—roughly one-eighth the duration of the fetal stage—concentrates high-risk cellular migrations and inductions, with over 90% of organ systems initiated, whereas the protracted fetal phase (approximately 30 weeks) prioritizes quantitative expansion, such as brain sulcation and myelinization, and qualitative enhancements like surfactant production in lungs for viability.[20] This temporal and processual divergence underscores the embryonic stage's foundational volatility versus the fetal stage's consolidative stability, as evidenced by viability thresholds remaining near zero before week 9 but emerging post-viability in later fetal development.[24]Human Fetal Development

Transition from Embryonic Period

The embryonic period in human development concludes at the end of the eighth week following fertilization, at which point the developing organism transitions to the fetal stage, characterized by the completion of primary organogenesis and the onset of substantial growth and structural refinement.[25][24] This demarcation aligns with Carnegie stage 23, after which the embryo measures approximately 23-30 mm in crown-rump length, exhibits a distinctly human contour with elongated limbs, separated digits on hands and feet, and nascent external genitalia.[25] The shift reflects a biological continuum rather than an abrupt change, but it is conventionally defined by the relative completion of gross organ formation, reducing teratogenic vulnerability while prioritizing histogenesis and functional maturation.[19] Key morphological milestones at this transition include the formation of the basic facial features, such as fused eyelids, external ear pinnae, and a closed neural tube, alongside the establishment of vital systems like a functional four-chambered heart with detectable ultrasound activity since week 5-6.[19][3] Internally, major organs—including the liver, kidneys, and intestines—have primordia in place, though they remain immature and non-viable outside the uterus; for instance, the gastrointestinal tract rotates into position, and early lung branching (pseudoglandular stage) begins.[19] This period's end also coincides with the disappearance of embryonic tail remnants and the initiation of scalp vascular patterns precursor to hair follicles, signifying a pivot from differentiation to proportional enlargement, with the fetus gaining length at rates exceeding 1 mm per day initially.[19] Physiologically, the transition underscores reduced risk from external disruptors post-organogenesis, as evidenced by epidemiological data showing most congenital malformations arising before week 9 post-fertilization, though functional deficits can still emerge from later insults.[22] Peer-reviewed embryological texts, such as those referencing standardized staging, emphasize this boundary's utility for clinical assessment, enabling prenatal diagnostics like ultrasound to confirm viability and structural integrity from week 9 onward.[26] The designation "fetus" thus denotes not a new entity but an advanced phase where cellular proliferation drives a 45-fold weight increase by term, supported by placental nutrient exchange maturing concurrently.[3]First Trimester Milestones

The fetal stage begins at around 9 weeks gestational age (7 weeks post-fertilization), marking the transition from the embryonic period where primary organogenesis is largely complete, shifting focus to growth, maturation, and structural refinement.[19] [3] By this point, the crown-rump length (CRL) measures approximately 2-3 cm, and the heartbeat is detectable via Doppler ultrasound.[27] [4] In week 9, the upper limbs elongate with elbow formation, toes become visible, and eyelids start developing, while nipples and hair follicles emerge on the skin.[27] [4] The head remains disproportionately large relative to the body, comprising nearly half its size, and essential organs continue expanding in preparation for functional maturation.[4] The CRL reaches about 16-18 mm.[27] By week 10, the head assumes a rounder shape, finger and toe webbing recedes as digits lengthen, and outer ears take form alongside advancing eyelid closure.[27] [4] Intestinal rotation occurs within the abdominal cavity, and facial features sharpen, with nostrils evident.[4] Fetal heart tones become audible via Doppler, indicating circulatory functionality.[4] Week 11 features a broadening face with widely spaced eyes, low-set ears, and fused eyelids that remain sealed until later gestation.[27] Tooth buds for primary dentition appear, the liver initiates red blood cell production, and external genitals differentiate, though not yet distinguishable by ultrasound.[27] [3] The fetus exhibits reflexive movements, including fist clenching, mouth opening, and joint flexion at knees, elbows, and ankles; the CRL approximates 50 mm, with weight around 8 grams.[27] [3] At week 12, the end of the first trimester, fingernails emerge, the facial profile gains definition with a distinct chin, and intestines fully migrate from the umbilical cord into the abdomen.[27] All major organs, limbs, bones, and muscles are present, with the liver producing bile and the fetus capable of swallowing and urinating amniotic fluid, evidencing early digestive and urinary system activity.[3] The CRL measures about 61 mm, and weight reaches approximately 14 grams, reflecting accelerated somatic growth.[27]Second Trimester Milestones

The second trimester of human fetal development, encompassing gestational weeks 13 through 27, is marked by rapid physical growth, refinement of organ systems, and the onset of coordinated movements. By the end of week 13, the fetus measures approximately 7-8 cm in crown-rump length and weighs about 23 grams, with ossification of bones beginning in the limbs and vertebrae.[28] Red blood cells start forming in the spleen and liver during week 14, supporting expanded circulation.[28] Bone development accelerates in weeks 15-16, with the skeleton hardening further and the fetus capable of making sucking motions and grasping. Facial features become more defined, including the formation of eyebrows, eyelashes, and nails; the fetus also begins to produce urine, which contributes to amniotic fluid volume.[28] By weeks 16-18, lanugo hair covers the body for temperature regulation, and vernix caseosa, a protective waxy coating, starts forming on the skin.[29] Maternal perception of fetal movement, known as quickening, typically occurs between weeks 16 and 20, though ultrasound detects movements as early as week 7-8; these include kicks, stretches, and somersaults.[28] [29] Sensory development advances with the maturation of the auditory system; by week 18, the fetus responds to external sounds, and by week 24-26, it can distinguish between loud and soft noises, with the inner ear fully formed.[28] Tooth buds appear under the gums, and the genitals are sufficiently developed for ultrasound visualization around week 18-20, allowing determination of sex in most cases.[30] The lungs begin producing surfactant precursors by week 24, a critical step for potential respiratory function post-birth.[28] Fetal viability emerges as a key milestone toward the end of the second trimester, with survival rates for preterm births increasing significantly after 23 weeks. At 23 weeks, survival is approximately 23-27%, rising to 42-59% at 24 weeks and 67-76% at 25 weeks, though with substantial risks of morbidity due to immature organ systems.[31] [32] By week 27, the fetus weighs about 900 grams, has open eyes capable of blinking, and exhibits rapid eye movements during sleep cycles, indicating neurological maturation.[28]Third Trimester Milestones

During the third trimester (weeks 28–40 of gestation), the human fetus undergoes rapid somatic growth, with weight tripling or quadrupling and length increasing by several inches, alongside critical maturation of organ systems to support independent viability post-birth.[11][33] The brain expands fourfold in volume, driven by gyral folding, axonal proliferation, and initial myelination, shifting metabolic priorities toward neural development.[34] Lungs transition to the alveolar stage, with type II pneumocytes ramping up surfactant synthesis from around 24–34 weeks to reduce surface tension and enable air breathing, though full maturity typically occurs by 36 weeks.[35][3] Key growth metrics include: at 28 weeks, average crown-rump length of 14.9 inches (37.9 cm) and weight of 2.7 pounds (1,210 g); by 36 weeks, 18.6 inches (47.3 cm) and 6.2 pounds (2,813 g); reaching term at approximately 20 inches (51 cm) and 8 pounds (3,619 g).[33] Adipose deposition smooths the skin and insulates against temperature loss, while the skeleton ossifies further, with epiphyseal centers appearing in long bones.[36] Viability improves markedly, with ~94% survival at 28 weeks under neonatal intensive care, rising to near 100% by term, contingent on lung and brain maturity.[33] Sensory and motor developments intensify: eyelids open and close by 28 weeks, allowing response to light; the fetus hears external sounds, exhibiting heart rate accelerations to maternal voice or music.[36] Movements become vigorous but less frequent due to spatial constraints, with the majority assuming cephalic presentation by 36 weeks.[11] The central nervous system regulates breathing efforts and thermoregulation, while bone marrow assumes primary erythropoiesis.[36] Fingernails and toenails reach their tips by 34–38 weeks, and lanugo sheds as vernix caseosa protects the skin.[36] These milestones reflect adaptive preparations for birth, with disruptions like preterm delivery risking respiratory distress from immature surfactant.[35]Fetal Physiology

Organogenesis and Functional Maturation

In the fetal stage, which commences at approximately week 9 post-fertilization, organogenesis transitions from foundational formation—largely completed during the embryonic period—to refinement, hypertrophy, and functional maturation essential for postnatal viability.[19] While basic organ rudiments emerge by week 8, the fetal phase emphasizes cellular proliferation, tissue differentiation, and the onset of physiological activities, such as circulation and excretion, preparing systems for independent function after birth.[19] This maturation is contingent on placental support, with fetal circulation bypassing underdeveloped lungs and partially the liver to prioritize oxygenation via maternal blood.[37] The cardiovascular system achieves structural integrity early in the fetal period, with the four-chambered heart fully partitioned by week 8 and capable of rhythmic contractions detectable as early as week 5-6, transitioning to coordinated fetal circulation by week 9.[38] Functional maturation involves shunting blood through the ductus venosus, foramen ovale, and ductus arteriosus, delivering oxygen-rich blood preferentially to the brain and heart while minimizing flow to the non-ventilating lungs.[37] By the third trimester, cardiac output increases substantially, supporting rapid fetal growth, though full adaptation to pulmonary circulation occurs only at birth with these shunts closing.[39] Respiratory organogenesis progresses through distinct phases during the fetal period: the pseudoglandular stage (weeks 5-16) establishes bronchial branching, followed by the canalicular stage (weeks 16-26) where vascularization and primitive alveoli form, enabling limited gas exchange potential.[40] Functional maturation accelerates in the saccular (weeks 26-36) and alveolar (week 36 to term) stages, with type II pneumocytes producing surfactant from around week 24 to reduce surface tension and prevent alveolar collapse postnatally; viability for extrauterine survival hinges on this surfactant synthesis, often immature before 34 weeks.[41] Lungs remain fluid-filled and non-gas-exchanging in utero, relying on amniotic fluid dynamics for growth.[42] Renal and hepatic systems demonstrate early functionality critical for homeostasis. The metanephric kidneys begin urine production by week 10-12, with glomeruli filtering fetal plasma and contributing to amniotic fluid volume, which expands to 800-1000 mL by term to support lung and musculoskeletal development.[43] The liver, initially dominant in hematopoiesis during the embryonic phase, shifts toward metabolic roles in the fetus, producing bile and glucose from week 12 onward, though it remains semifunctional with much nutrient processing deferred to the placenta.[42] By mid-gestation, the gastrointestinal tract matures to permit swallowing of amniotic fluid around week 12, fostering gut motility and meconium accumulation.[43] Neurological maturation underpins sensory and reflexive capabilities, with the central nervous system exhibiting synaptic formation and myelination progressing from the spinal cord upward, enabling fetal movements detectable by week 8-9 and coordinated responses by the second trimester.[4] Endocrine organs, such as the thyroid and adrenals, activate hormone production—thyroid hormone synthesis begins around week 12 to regulate metabolism, while adrenal maturation in the third trimester prepares for stress responses via cortisol surges that aid lung maturation.[21] Overall, functional immaturity in key systems like the lungs and liver underscores the fetus's dependence on maternal physiology until term, with preterm delivery risking deficits in these processes.[44]Neurological and Sensory Development

The human fetal brain undergoes rapid structural and functional maturation during the fetal period, building on embryonic foundations. Neurogenesis, the production of neurons, peaks at 15-16 weeks gestation and persists until the late second trimester, occurring primarily in the subependymal region of the lateral ventricles with maximal rates at 17-18 weeks.[45] Neuron migration follows, with cells traveling from the subventricular zone to the cortical plate via radial and tangential pathways between 12 and 20 weeks.[45] Synaptogenesis, the formation of neural synapses, initiates around 22 weeks and continues postnatally, enabling the establishment of cortical circuits for processing sensory inputs and coordinating movements.[45] Cortical folding commences at approximately 16 weeks, with pronounced morphological changes in the insular cortex and peri-Sylvian regions from 20 to 26 weeks, regions associated with sensory integration and language precursors; frontal lobe gyri, such as the middle and superior frontal, actively fold between 26 and 28 weeks.[46] Overall brain network efficiency and strength increase progressively from 20 to 40 weeks postmenstrual age, transitioning from posterior-dominant (sensorimotor) to more anterior (associative) connectivity.[47] Myelination, the process insulating neural axons for faster signal transmission, begins in the second trimester but accelerates primarily postnatally, with neuroglial proliferation prominent in the third trimester.[45] Somatosensory development, encompassing touch and proprioception, emerges earliest among the senses, with reflexive responses to perioral stimulation (e.g., mouth region) detectable by 7-8 weeks gestation and extending to facial areas, palms, soles, and limbs by 11-13 weeks, as evidenced by twin interactions and body self-touch.[48] Physiological somatosensory responses are recordable by 14 weeks, supporting hierarchical processing in the somatosensory cortex by 20-26 weeks as layer IV differentiates.[49][50] Auditory capabilities develop with cochlear functionality by 20-22 weeks, enabling sound detection; initial heart rate and movement responses to tones (e.g., 500 Hz) occur around 19 weeks, progressing to discriminatory reactions to maternal voice or specific phonemes like "LA" by 25 weeks, with broader responsiveness from 21-33 weeks.[51][48][52] Visual system maturation includes eye movements starting at 16-18 weeks, eyelid opening at 23-24 weeks, and initial light detection thereafter; pupils constrict and dilate by 31 weeks, permitting directed responses to visual stimuli under adequate illumination, though full acuity refines postnatally.[48][53][54] Gustatory and olfactory senses functionalize in the second trimester, as fetuses swallow amniotic fluid containing flavor compounds from maternal diet, with evidence of chemosensory discrimination by mid-gestation; olfactory processing contributes to responsiveness by 21-33 weeks.[48][55]Evidence of Fetal Pain and Responsiveness

Nociceptors, specialized sensory receptors for detecting potentially harmful stimuli, begin forming in the human fetus as early as 7 weeks gestation, with functional spinal reflex pathways established by 11-12 weeks, enabling withdrawal responses to noxious touch.[56] By 12 weeks, thalamic projections to the subplate zone— a transient structure beneath the developing cortex—emerge, potentially supporting rudimentary sensory processing akin to thalamocortical functions observed in preterm neonates.[57] These developments allow for behavioral responses such as limb flexion or head turning away from invasive stimuli during procedures like amniocentesis, as documented in ultrasound observations.[58] Fetal responsiveness to external stimuli manifests progressively. Auditory responses, including heart rate acceleration and movement cessation, are detectable from 19 weeks, while visual responses to light emerge around 26-28 weeks, coinciding with eyelid opening and retinal maturation.[59] Tactile sensitivity increases with skin innervation; by 14-15 weeks, the fetus exhibits coordinated movements and stress hormone elevations (e.g., cortisol) in reaction to needle insertions during fetal blood sampling, indicating physiological arousal.[60] Electroencephalographic (EEG) patterns resembling adult-like sensory processing appear in preterm infants as young as 22-24 weeks, suggesting capacity for stimulus discrimination beyond mere reflexes.[61] The capacity for conscious pain perception remains contested, hinging on whether subcortical circuits suffice or if thalamocortical connections—maturing between 23-30 weeks—are requisite for the affective dimension of pain.[62] Proponents of earlier sentience cite preterm neonate data, where infants at 21-23 weeks display behavioral, hormonal, and autonomic pain indicators during procedures, implying analogous in utero capability absent cortical maturity barriers.[61] [63] Conversely, reviews emphasizing cortical necessity argue that integrated pain experience requires thalamocortical axons reaching the cortical plate by 24-28 weeks, as subplate activity alone may not confer qualia.[64] [57] Empirical challenges include ethical limits on direct fetal testing, reliance on indirect measures like fetal magnetocardiography showing stress desynchronization by 20 weeks, and observations of fetal opioid administration reducing distress in surgeries.[58]| Gestational Age | Key Development | Evidence Type |

|---|---|---|

| 7-8 weeks | Nociceptor formation and initial sensory nerves | Histological studies[56] |

| 11-12 weeks | Spinal withdrawal reflexes; subplate projections | Ultrasound and neuroanatomical tracing[59] [57] |

| 14-20 weeks | Hormonal stress responses to invasive stimuli; coordinated movements | Blood sampling procedures; cortisol assays[60] |

| 23-28 weeks | Thalamocortical connections; EEG sensory patterns | Neuroimaging in preterms; fetal EEG[61] [62] |

Medical Interventions and Health

Diagnosis of Fetal Conditions

Prenatal diagnosis of fetal conditions encompasses screening tests, which assess risk without confirming diagnosis, and invasive diagnostic procedures that provide definitive results. Screening methods include ultrasound imaging, maternal serum analyte measurements, and non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) via cell-free fetal DNA analysis, typically offered from 10 weeks gestation.[66] Diagnostic tests, such as chorionic villus sampling (CVS) and amniocentesis, involve sampling fetal cells for karyotyping, microarray analysis, or sequencing to detect chromosomal abnormalities, genetic mutations, or infections with near-100% accuracy for targeted conditions.[67] These approaches enable early identification of anomalies like aneuploidies (e.g., trisomy 21), neural tube defects, and structural malformations, informing parental decisions on continuation, preparation, or intervention.[68] Ultrasound remains the cornerstone for detecting structural anomalies, performed routinely at 18-22 weeks (anatomy scan) with optional first-trimester assessment. It identifies major defects such as cardiac anomalies, spina bifida, and limb reductions, achieving sensitivities of 40-84% when combining first- and second-trimester scans, depending on the organ system and population risk; specificity exceeds 99% for confirming normal anatomy.[69] Limitations include operator dependence and reduced efficacy for subtle or late-developing issues, necessitating follow-up with advanced imaging like 3D ultrasound or fetal MRI in equivocal cases.[70] Biochemical screening integrates maternal blood tests with ultrasound, such as first-trimester combined screening (nuchal translucency plus PAPP-A and hCG levels) detecting 85-90% of Down syndrome cases at a 5% false-positive rate.[71] Second-trimester quad screening evaluates AFP, hCG, estriol, and inhibin A for risks of trisomies and open neural tube defects, with sensitivities around 80% for trisomy 21.[72] NIPT, analyzing cell-free fetal DNA in maternal plasma from 10 weeks, screens for common aneuploidies with >99% sensitivity and <1% false-positive rate for trisomy 21, outperforming traditional methods in high-risk pregnancies and increasingly used in average-risk groups.[73] Expanded NIPT panels detect sex chromosome anomalies and microdeletions, though positive predictive values drop for rarer conditions (e.g., 40-50% for some microdeletions), warranting confirmatory invasive testing.[74] Risks are negligible, limited to maternal venipuncture, making it preferable over invasive options for initial risk stratification.[75] CVS, performed at 10-13 weeks via transabdominal or transcervical aspiration of placental villi, diagnoses chromosomal and molecular abnormalities with high accuracy but carries a miscarriage risk of 0.5-1%, higher than background rates.[76] Amniocentesis, conducted at 15-20 weeks by extracting amniotic fluid, offers similar diagnostic yield for karyotype, FISH, or PCR-based tests, with a lower procedure-related miscarriage risk of 0.1-0.3%.[77] Both procedures detect over 99% of targeted aneuploidies but confer infection or preterm labor risks in <1% of cases.[78] Post-2023 advances include integration of genomic sequencing with imaging for sonographically abnormal fetuses, enhancing detection of monogenic disorders via exome analysis on amniocentesis samples, and refined AI-assisted ultrasound for anomaly phenotyping.[79] These developments, such as expanded carrier screening and treatable trait identification, shift toward precision diagnostics, though access varies and false positives in low-prevalence conditions persist, emphasizing the need for genetic counseling.[80]Fetal Surgery Techniques

Fetal surgery encompasses a range of procedures performed on the fetus in utero to correct or mitigate congenital anomalies, with techniques broadly classified as open, fetoscopic (minimally invasive), and percutaneous image-guided interventions.[81] Open fetal surgery involves a maternal laparotomy and hysterotomy to expose the fetus, allowing direct surgical access under general anesthesia, typically reserved for severe conditions like myelomeningocele (spina bifida) or congenital diaphragmatic hernia where immediate structural repair is needed.[82] This approach, first developed in the 1980s at institutions like the UCSF Fetal Treatment Center, demonstrated efficacy in the Management of Myelomeningocele Study (MOMS trial, completed 2011), where prenatal repair before 26 weeks' gestation reduced the need for ventriculoperitoneal shunts by 42% and improved independent ambulation rates to 42% at 30 months compared to postnatal surgery.[83] However, it carries risks including maternal complications like pulmonary edema (13% incidence) and preterm delivery (median 34 weeks), often necessitating cesarean sections.[84] Fetoscopic surgery, or "fetendo," employs small trocars (3-5 mm) inserted through the maternal abdomen under ultrasound and endoscopic guidance, minimizing uterine disruption and enabling procedures like laser photocoagulation for twin-twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS) or endoscopic repair of spina bifida.[85] For TTTS, selective laser coagulation of placental anastomoses achieves survival rates of 60-70% for at least one twin when performed before 26 weeks, surpassing amnioreduction techniques.[86] In spina bifida cases, fetoscopic repairs, advanced since 2018, show comparable fetal neurologic benefits to open surgery—such as reduced hindbrain herniation—but with lower maternal morbidity, including 52% vaginal delivery rates versus 0% in open cohorts, though they may require longer operative times (average 4-6 hours).[87] A 2025 meta-analysis found open approaches superior for fetal outcomes like shunt independence but fetoscopic methods preferable for maternal recovery, with ongoing trials evaluating hybrid techniques.[88] Percutaneous techniques involve needle-based interventions under imaging, such as vesico-amniotic shunting for lower urinary tract obstruction (LUTO), where a shunt drains fetal bladder urine to the amniotic space, improving pulmonary hypoplasia survival to 50-60% in select cases post-18 weeks.[89] The ex utero intrapartum treatment (EXIT) procedure, a hybrid near-term intervention, partially delivers the fetus via hysterotomy while maintaining placental circulation for 5-60 minutes to secure the airway in cases of congenital high airway obstruction, achieving 95% survival when combined with multidisciplinary teams.[81] Overall, technique selection depends on gestational age (ideally 18-28 weeks), anomaly severity, and center expertise, with randomized data emphasizing improved long-term function but persistent risks of fetal loss (5-10%) and maternal hysterectomy (<1%).[90] Advances as of 2025 focus on refining fetoscopy to balance efficacy and safety, supported by registries tracking over 1,000 cases annually worldwide.[91]Recent Advances in Fetal Medicine (Post-2023)

In 2024, advancements in fetal surgery for spina bifida included the integration of stem cell therapies during in-utero procedures. At UC Davis Health, surgeons performed the world's first fetal surgery incorporating a mesenchymal stem cell patch applied directly to the spinal cord defect, as part of the CuRe clinical trial initiated in 2022 but yielding key outcomes reported in 2024 and early 2025.[92] This approach, tested on fetuses around 24-26 weeks gestation, aims to enhance neural repair beyond traditional closure techniques, with preliminary data from trial participants showing improved motor function in early infancy.[93] Similarly, Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) Doernbecher Children's Hospital conducted the Pacific Northwest's first in-utero spina bifida repair in September 2024, demonstrating feasibility in regional centers and correlating with reduced hydrocephalus rates postnatally.[94] Progress in fetal gene therapy emerged prominently in 2024, with preclinical studies advancing toward clinical translation for genetic disorders. Researchers at UC Davis demonstrated successful delivery of CRISPR-Cas9-based gene editing tools to fetal brain cells in animal models, targeting faulty genes in neurodevelopmental conditions by injecting nanoparticles via the amniotic fluid, achieving up to 40% editing efficiency without maternal immune rejection.[95] UCSF surgeon Tippi MacKenzie, previously focused on fetal surgery, pivoted to in-utero gene editing trials, emphasizing its potential to treat monogenic diseases like sickle cell anemia before birth, with safety data from large animal models supporting human application by late 2024.[96] Additionally, a December 2024 study reported placental nanoparticle delivery of IGF1 gene therapy in guinea pig models corrected fetal growth restriction, restoring placental function and fetal weight by 25-30% in affected pregnancies.[97] Diagnostic enhancements post-2023 incorporated routine exome sequencing for fetuses slated for therapy, as debated and endorsed at the 2024 International Society for Prenatal Diagnosis meeting. This approach identifies underlying genetic causes in up to 20% of cases previously deemed idiopathic, guiding personalized interventions and improving prognostic accuracy.[98] In imaging, refined fetal MRI protocols advanced brain anomaly detection, with 2024 techniques enabling quantitative diffusion tensor imaging to assess white matter tract integrity as early as 20 weeks, correlating with neurodevelopmental outcomes in cohorts exceeding 500 cases.[99] These developments, while promising, underscore ongoing challenges in long-term efficacy and ethical oversight, with clinical trials emphasizing multidisciplinary evaluation to mitigate risks like preterm labor.[100]Ethical and Philosophical Debates

Biological Continuity from Conception

At the moment of fertilization, when a sperm nucleus fuses with an ovum nucleus, a zygote forms possessing a complete human genome consisting of 46 chromosomes arranged into 23 pairs, distinct from that of either parent.[101] This zygote represents the onset of a new, individuated human organism, genetically unique and self-directing its own development toward maturity without acquiring further genetic material from the mother.[6] Empirical observations in embryology confirm that this entity exhibits continuous, organized growth through stages—cleavage to morula, blastocyst formation, and implantation—without interruption or transformation into a different type of organism.[7] Biological continuity is evidenced by the zygote's intrinsic epigenetic and genetic programming, which guides progressive maturation of cellular and organ systems while maintaining the same nuclear DNA throughout prenatal development.[101] Unlike gametes, which cease independent existence upon fusion, the zygote actively initiates metabolic processes, including transcription of its genome within hours, marking the start of organismal life distinct from parental contributions.[102] Surveys of biologists indicate a strong consensus, with 95% affirming that a human's biological life commences at fertilization, reflecting standard embryological textbooks that describe the zygote as the first stage of the human life cycle.[103] This view prioritizes observable cellular and genetic events over philosophical or viability-based criteria, underscoring causal continuity from a single-celled entity to a multicellular fetus. Critiques positing that human life does not "begin" at fertilization—arguing instead for a pre-existing continuum from gametes—overlook the qualitative shift: the zygote's totipotent cells differentiate into a unified organism capable of all human potentials, whereas oocytes and sperm are mere reproductive cells lacking such holistic organization.[104] Peer-reviewed embryology literature consistently traces developmental landmarks back to this fertilization event, with no empirical evidence of a biological discontinuity thereafter, as the same genomic blueprint persists through embryogenesis, fetal stages, birth, and adulthood.[7][105]Arguments for Fetal Personhood Based on Empirical Data

Empirical data from developmental biology demonstrate that a distinct human organism arises at fertilization, when the sperm's 23 chromosomes combine with the oocyte's 23 to form a unique diploid genome of 46 chromosomes, initiating species-specific self-directed development. This zygote possesses all genetic instructions necessary for maturation into an adult human, distinguishing it ontologically from the parental gametes and marking the commencement of a continuous biological trajectory. Surveys of biologists indicate that a substantial majority—approximately 95%—affirm that a human's life begins at fertilization, reflecting consensus in the field on this foundational event.[103][106][6] Embryology textbooks consistently describe the fertilized ovum as the starting point of human development, with the embryo exhibiting totipotency initially—capable of forming all tissues and organs—and progressing through cleavage, blastocyst formation, and implantation without acquiring novel genetic material that would redefine its humanity. This continuity lacks empirical discontinuities, such as sudden emergence of human traits at birth or viability; instead, postnatal infants share comparable dependencies and developmental incompleteness, yet are not denied personhood. Genetic and epigenetic analyses further confirm the embryo's individuality, as its chromosomal and molecular profile remains stable across stages, supporting arguments that personhood inheres in the human organism from its inception rather than arbitrary thresholds.[107][101] Neurological milestones provide additional empirical support, with detectable brain waves recorded as early as 6 weeks gestation via EEG, indicating organized electrical activity in the central nervous system. Synaptic formation begins around 5 weeks, facilitating rudimentary neural signaling, while thalamocortical connections—linked to sensory integration—emerge by 24-28 weeks, enabling complex responsiveness. These data refute claims of fetal inertness, as the progressive maturation of brain function mirrors postnatal development and evidences the fetus's capacity for experience and agency, akin to attributes conferring personhood postnatally. Peer-reviewed analyses of fetal EEG patterns underscore this early functionality, challenging location- or capacity-based denials of personhood by highlighting biological equivalence in human neural ontogeny.[108][109][110]Critiques of Viability-Centric and Location-Based Justifications

Critiques of viability as a moral threshold for attributing rights to the fetus emphasize its contingency on medical technology rather than intrinsic biological properties. The gestational age at which viability is assessed has decreased over time due to advances in neonatal intensive care; for instance, survival rates for fetuses at 22 weeks gestation reached approximately 20-30% in specialized centers by 2020, compared to near-zero rates before the 1980s.[111] This shifting boundary renders viability an unreliable marker for moral status, as it implies that personhood could retroactively apply earlier with further technological progress, such as artificial wombs, undermining any claim to a fixed ethical line.[112] Philosophers and ethicists argue that viability confuses developmental potential with external support systems, failing to address the continuous causal chain of human organism development from fertilization, where genetic uniqueness and organismal integrity exist independently of survival odds.[113] Moreover, viability lacks grounding in empirical markers of humanity, such as the presence of a unique human genome established at conception, which persists unchanged through gestation. Reliance on viability as a cutoff is critiqued for its indeterminacy in edge cases, including extreme prematurity, where survival depends on probabilistic factors like access to care rather than inherent qualities, leading to inconsistent moral applications across jurisdictions and eras.[112] For example, legal frameworks tying abortion limits to viability, as in pre-Dobbs U.S. precedents, have been faulted for embedding a criterion that evolves with science but erodes first-principles reasoning about the fetus as a distinct human entity entitled to protection based on its nature, not contingent capabilities.[114] Location-based justifications, which hinge moral status on the fetus's position relative to the birth canal, are similarly challenged for their arbitrariness, as no substantive biological or ontological transformation occurs at birth to justify a sudden shift in rights. The human organism remains the same entity—genetically identical and developmentally continuous—before and immediately after delivery, with newborns exhibiting comparable dependence on caregivers for survival.[115] Ethicists contend that privileging location equates to endorsing an ad hoc spatial criterion, akin to denying rights based on enclosure, which fails causal realism: the fetus's vulnerability stems from immaturity, not uterine position, and post-birth infants share this without forfeiting protections against homicide.[116] This approach is further undermined by medical realities, such as fetal surgery, where pre-viable fetuses are treated as patients with independent interests, receiving interventions like spina bifida repairs as early as 23 weeks, indicating tacit recognition of their status irrespective of location.[115] Critics, including legal scholars, argue that location-based thresholds invite absurdities, such as permitting harm if the fetus is partially delivered but not fully, highlighting how such criteria prioritize procedural happenstance over empirical evidence of the fetus's status as a human being with developing capacities for sentience and relationality.[117] Advances like ex utero gestation further erode location's relevance, as they decouple survival from the womb without altering the entity's moral claims.[115]Legal Frameworks

Historical Evolution of Fetal Rights

In ancient legal systems, such as those in primitive societies and early civilizations, personhood and status were generally conferred only at birth, with little to no independent recognition of the fetus; for instance, deformed fetuses could be abandoned or killed without legal consequence.[118] Roman law treated the fetus as an extension of the mother's body, lacking separate legal personality, though a legal fiction allowed conditional rights—such as inheritance from a deceased father—if the child was subsequently born alive.[118] This approach emphasized potentiality tied to live birth rather than independent fetal status, influencing later Western traditions amid emerging Christian views on the sanctity of life, which began to advocate protections against fetal harm without granting full personhood.[118] Under English common law, which shaped much of Anglo-American jurisprudence, the unborn child ("infant en ventre sa mere") received civil protections, particularly in property and inheritance matters, as articulated by William Blackstone in his 1769 Commentaries on the Laws of England, where such a child was deemed "born" for purposes of legacies, estates, and trusts if it later came to full term alive.[119] Cases like Wallis v. Hodson (1736) affirmed these rights, allowing the unborn to claim copyhold estates or share in tenancies.[119] In criminal law, however, the "born alive" rule prevailed, denying homicide liability for fetal death unless the child survived birth and then succumbed to injuries sustained in utero, as per Blackstone and earlier authorities like Edward Coke.[119] Quickening—fetal movement around 16-20 weeks—marked a threshold for misdemeanor liability in abortion or harm, formalized in the 1803 Lord Ellenborough's Act, which elevated post-quickening destruction to felony status if it led to live birth and subsequent death.[118] By the 19th century, as abortion statutes tightened—removing the quickening distinction in England by 1837 and imposing felony penalties—fetal protections expanded in tort law, recognizing wrongful death claims for viable fetuses in some jurisdictions, though full personhood remained absent.[118] In the United States, inheriting common law traditions, states codified inheritance rights for the unborn, as in California's Probate Code §250, while criminal law evolved toward explicit feticide provisions; California's 1970 amendment to Penal Code §187 redefined murder to encompass the unlawful killing of a fetus, predating broader trends.[119] The 20th century saw further divergence, with therapeutic abortion allowances by the 1940s for maternal health risks, yet growing recognition of fetal viability as a state interest post-Roe v. Wade (1973), which balanced maternal privacy against potential life after viability (around 24 weeks).[118][120] Modern developments accelerated fetal rights in contexts of third-party violence, distinct from abortion: by the 1980s, states like Minnesota (1987) enacted explicit fetal homicide laws treating unborn children as victims, culminating in the federal Unborn Victims of Violence Act of 2004, which recognizes a "child in utero" as a separate victim in federal crimes of violence against pregnant women, applicable from fertilization onward.[121][122] This legislation, signed by President George W. Bush, addressed gaps where perpetrators faced no added penalty for fetal harm, reflecting empirical recognition of fetal vulnerability without conferring blanket personhood.[122] By 2022, 38 states had fetal homicide statutes, often excluding maternal actions to avoid conflicting with abortion access.[123] Overall, the trajectory shifted from conditional civil fictions and birth-tied criminality to targeted protections against external harm, driven by medical advances confirming fetal viability and responsiveness, though personhood debates persist amid institutional biases favoring maternal autonomy in academic and media sources.[120]Contemporary Laws on Fetal Protection

In the United States, federal law under the Unborn Victims of Violence Act of 2004 recognizes an unborn child at any stage of development as a separate victim in cases of certain federal crimes committed against a pregnant woman, allowing for additional charges such as murder or manslaughter if the fetus is harmed or killed.[124] This statute applies to offenses like those under the Uniform Code of Military Justice and interstate domestic violence, but explicitly excludes consensual abortions or acts by the mother. As of 2024, 39 states have enacted fetal homicide laws that similarly treat the intentional killing of a fetus by a third party as a distinct offense, often equivalent to homicide regardless of gestational age, though some limit applicability to post-quickening or viability.[121] These laws have led to prosecutions in cases of assault, drunk driving, or murder where fetal death results, with examples including convictions under California's penal code for fetal injury during battery on a pregnant woman.[125] State-level expansions post-2022 Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization decision have reinforced fetal protections in non-abortion contexts, such as enhanced penalties for crimes causing fetal harm. For instance, in 2023, North Carolina and Nebraska implemented restrictions that indirectly bolster fetal safeguards by limiting procedures while maintaining homicide statutes.[126] Additionally, 17 states apply fetal rights to both criminal and civil law, enabling wrongful death suits for fetal loss due to negligence, as seen in judicial decisions recognizing fetuses as legal persons for tort claims from fertilization onward.[125] Controversially, some jurisdictions prosecute maternal conduct endangering the fetus, such as substance abuse, under child endangerment or chemical endangerment laws, with over 1,500 cases documented since 2000, though critics argue these disproportionately affect low-income women without improving outcomes.[127][128] Internationally, fetal protection varies, with many common-law jurisdictions prohibiting feticide through legacy statutes like the UK's Offences Against the Person Act 1861, which criminalizes procuring a miscarriage via unlawful means, punishable by life imprisonment, and extends to third-party harm post-quickening. Australia and New Zealand have specific fetal homicide provisions, treating the killing of a fetus after 20 weeks as manslaughter or murder, as enacted in Queensland's Criminal Code in 2018 and New Zealand's Crimes Act amendments.[129] The American Convention on Human Rights, ratified by 25 Latin American states, mandates protection of the right to life "in general from the moment of conception," influencing national laws in countries like Chile and El Salvador, where fetal harm in violence is prosecutable separately. In contrast, Canada's Criminal Code does not recognize fetal homicide distinctly, relying on general charges against the mother or assailant, a stance upheld by the 2010 Supreme Court rejection of fetal personhood bills.[130] Emerging legislation as of 2025 includes U.S. federal proposals like H.R. 686, the Protecting the Dignity of Unborn Children Act, which would criminalize reckless disposal of fetal remains, and the Life at Conception Act affirming rights from fertilization, though neither has passed.[131][132] These reflect ongoing debates, where fetal protection laws prioritize empirical harm to developing human life over location-based or consent-based exemptions, yet face challenges in uniform application due to jurisdictional variances and source biases in advocacy-driven reporting.[133]Fetal Homicide and Personhood Legislation