Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Prostatic urethra.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Prostatic urethra

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

| Prostatic urethra | |

|---|---|

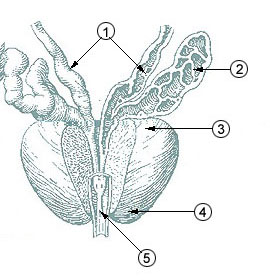

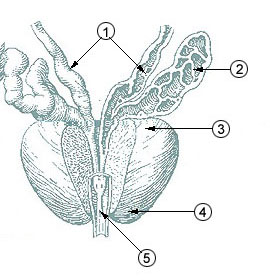

The male urethra laid open on its anterior (upper) surface. (Prostatic part labeled at upper right.) | |

| |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | pars prostatica urethrae |

| TA98 | A09.4.02.004 |

| TA2 | 3445 |

| FMA | 19673 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The prostatic urethra, the widest and most dilatable part of the urethra canal, is about 3 cm long.

It runs almost vertically through the prostate from its base to its apex, lying nearer its anterior than its posterior surface; the form of the canal is spindle-shaped, being wider in the middle than at either extremity, and narrowest below, where it joins the membranous portion.

A transverse section of the canal as it lies in the prostate is horse-shoe-shaped, with the convexity directed forward.

The keyhole sign, in ultrasound, is associated with a dilated bladder and prostatic urethra.

Additional images

[edit]References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 1234 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 1234 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

External links

[edit]- Anatomy image: malepel2-4 at the College of Medicine at SUNY Upstate Medical University

- Cross section image: pelvis/pelvis-e12-15—Plastination Laboratory at the Medical University of Vienna

- Anatomy photo:44:05-0201 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "The Male Pelvis: The Prostate Gland"

- Chronic Prostatitis - Four Major Symptoms and Three Lifestyle To Follow

Prostatic urethra

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

The prostatic urethra is the proximal segment of the male urethra, extending from the neck of the urinary bladder through the central portion of the prostate gland, and serving as a conduit for both urine and semen.[1][2] It measures approximately 3 to 4 cm in length and is the widest part of the male urethra, facilitating the passage of fluids while being enveloped by the prostate's glandular and stromal tissues.[2]

Anatomically, the prostatic urethra is positioned inferior to the bladder within the lesser pelvis, traversing the prostate from its base to its apex, and is bordered superiorly by the bladder neck and inferiorly by the external urethral sphincter.[3] Histologically, it is lined by transitional epithelium known as urothelium, which transitions to pseudostratified columnar epithelium toward its distal end, and it features prominent internal structures such as the urethral crest (a longitudinal ridge along its posterior wall), the seminal colliculus (or verumontanum, a mound on the crest where the ejaculatory ducts open), the prostatic utricle (a small pouch in the colliculus), and the orifices of the prostatic ducts that drain prostatic secretions.[2] These elements are critical for integrating urinary and reproductive functions, as the urethra here receives contributions from the ejaculatory ducts during semen emission.[3]

The prostatic urethra's location within the prostate makes it clinically significant in conditions like benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), where glandular enlargement can compress it and obstruct urine flow, and it is also relevant in prostate cancer staging due to its proximity to the peripheral and transition zones of the gland.[3] Surgical interventions, such as transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP), often target this segment to alleviate obstruction while preserving sphincter function.[2]