Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

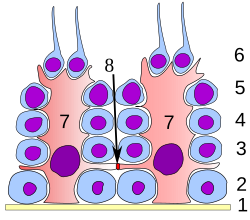

Spermatid

View on Wikipedia| Spermatid | |

|---|---|

Germinal epithelium of the testicle. 1: basal lamina 2: spermatogonia 3: spermatocyte 1st order 4: spermatocyte 2nd order 5: spermatid 6: mature spermatid 7: Sertoli cell 8: tight junction (blood testis barrier) | |

| |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D013087 |

| FMA | 72294 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The spermatid is the haploid male gametid that results from division of secondary spermatocytes. As a result of meiosis, each spermatid contains only half of the genetic material present in the original primary spermatocyte.

Spermatids are connected by cytoplasmic material and have superfluous cytoplasmic material around their nuclei.

When formed, early round spermatids must undergo further maturational events to develop into spermatozoa, a process termed spermiogenesis (also termed spermeteliosis).

The spermatids begin to grow a living thread, develop a thickened mid-piece where the mitochondria become localised, and form an acrosome. Spermatid DNA also undergoes packaging, becoming highly condensed. The DNA is packaged firstly with specific nuclear basic proteins, which are subsequently replaced with protamines during spermatid elongation. The resultant tightly packed chromatin is transcriptionally inactive.

In 2016 scientists at Nanjing Medical University claimed they had produced cells resembling mouse spermatids artificially from stem cells. They injected these spermatids into mouse eggs and produced pups.[1]

During spermatid haploid genome remodeling, the majority of histones are replaced by protamines, and the DNA is compacted. During this compaction, transient single- and double-strand breaks are introduced into the sperm DNA.[2] The conventional non-homologous end joining pathway for repairing double-strand breaks is not available for elongated spermatids. However, spermatids can carry out limited repair of exogenous and programmed double-strand breaks using an alternative error-prone non-homologous end joining repair pathway.[3] If DNA strand breaks persist in mature sperm, the result can be increased sperm DNA fragmentation which is associated with impaired fertility and an increased incidence of miscarriage.[4]

DNA repair

[edit]As postmeiotic germ cells develop to mature sperm they progressively lose the ability to repair DNA damage that may then accumulate and be transmitted to the zygote and ultimately the embryo.[5] In particular, the repair of DNA double-strand breaks by the non-homologous end joining pathway, although present in round spermatids, appears to be lost as they develop into elongated spermatids.[6]

Additional images

[edit]-

Scheme showing analogies in the process of maturation of the ovum and the development of the Genyo spermatids (young spermatozoa)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Cyranoski, David (25 February 2016). "Researchers claim to have made artificial mouse sperm in a dish". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2016.19453. S2CID 87014225. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ^ Gouraud A, Brazeau MA, Grégoire MC, Simard O, Massonneau J, Arguin M, Boissonneault G (2013). ""Breaking news" from spermatids". Basic Clin Androl. 23: 11. doi:10.1186/2051-4190-23-11. PMC 4349474. PMID 25780573.

- ^ Ahmed EA, Scherthan H, de Rooij DG (December 2015). "DNA Double Strand Break Response and Limited Repair Capacity in Mouse Elongated Spermatids". Int J Mol Sci. 16 (12): 29923–35. doi:10.3390/ijms161226214. PMC 4691157. PMID 26694360.

- ^ Aitken RJ, De Iuliis GN (January 2010). "On the possible origins of DNA damage in human spermatozoa". Mol Hum Reprod. 16 (1): 3–13. doi:10.1093/molehr/gap059. PMID 19648152.

- ^ Marchetti F, Wyrobek AJ (2008). "DNA repair decline during mouse spermiogenesis results in the accumulation of heritable DNA damage". DNA Repair (Amst.). 7 (4): 572–81. doi:10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.12.011. PMID 18282746. S2CID 1316244.

- ^ Ahmed EA, Scherthan H, de Rooij DG (December 2015). "DNA Double Strand Break Response and Limited Repair Capacity in Mouse Elongated Spermatids". Int J Mol Sci. 16 (12): 29923–35. doi:10.3390/ijms161226214. PMC 4691157. PMID 26694360.

External links

[edit]- Histology image: 17804loa – Histology Learning System at Boston University - "Male Reproductive System: testis, early spermatids"

- Histology image: 17805loa – Histology Learning System at Boston University - "Male Reproductive System: testis, late spermatids"

- Histology at okstate.edu