Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Urination

View on Wikipedia

Urination is the release of urine from the bladder through the urethra in placental mammals,[1][2]: 38, 364 or through the cloaca in other vertebrates.[3][1] It is the urinary system's form of excretion. It is also known medically as micturition,[4] voiding, uresis, or, rarely, emiction, and known colloquially by various names including peeing, weeing, pissing, and euphemistically number one. The process of urination is under voluntary control in healthy humans and other animals, but may occur as a reflex in infants, some elderly individuals, and those with neurological injury. It is normal for adult humans to urinate up to seven times during the day.[5]

In some animals, in addition to expelling waste material, urination can mark territory or express submissiveness. Physiologically, urination involves coordination between the central, autonomic, and somatic nervous systems. Brain centres that regulate urination include the pontine micturition center, periaqueductal gray, and the cerebral cortex.

Anatomy and physiology

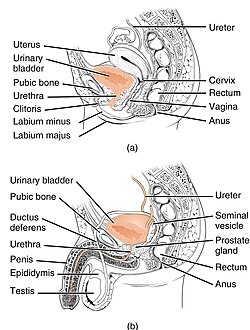

[edit]Anatomy of the bladder and outlet

[edit]The main organs involved in urination are the urinary bladder and the urethra. The smooth muscle of the bladder, known as the detrusor, is innervated by sympathetic nervous system fibers from the lumbar spinal cord and parasympathetic fibers from the sacral spinal cord.[6] Fibers in the pelvic nerves constitute the main afferent limb of the voiding reflex; the parasympathetic fibers to the bladder that constitute the excitatory efferent limb also travel in these nerves. Part of the urethra is surrounded by the male or female external urethral sphincter, which is innervated by the somatic pudendal nerve originating in the cord, in an area termed Onuf's nucleus.[7]

Smooth muscle bundles pass on either side of the urethra, and these fibers are sometimes called the internal urethral sphincter, although they do not encircle the urethra. Further along the urethra is a sphincter of skeletal muscle, the sphincter of the membranous urethra (external urethral sphincter). The bladder's epithelium is termed transitional epithelium which contains a superficial layer of dome-like cells and multiple layers of stratified cuboidal cells underneath when evacuated. When the bladder is fully distended the superficial cells become squamous (flat) and the stratification of the cuboidal cells is reduced in order to provide lateral stretching.

Physiology

[edit]The physiology of micturition and the physiologic basis of its disorders are subjects about which there is much confusion, especially at the supraspinal level. Micturition is fundamentally a spinobulbospinal reflex facilitated and inhibited by higher brain centers such as the pontine micturition center and, like defecation, subject to voluntary facilitation and inhibition.[16]

In healthy individuals, the lower urinary tract has two discrete phases of activity: the storage (or guarding) phase, when urine is stored in the bladder; and the voiding phase, when urine is released through the urethra. The state of the reflex system is dependent on both a conscious signal from the brain and the firing rate of sensory fibers from the bladder and urethra.[16] At low bladder volumes, afferent firing is low, resulting in excitation of the outlet (the sphincter and urethra), and relaxation of the bladder.[17] At high bladder volumes, afferent firing increases, causing a conscious sensation of urinary urge. Individual ready to urinate consciously initiates voiding, causing the bladder to contract and the outlet to relax. Voiding continues until the bladder empties completely, at which point the bladder relaxes and the outlet contracts to re-initiate storage.[16] The muscles controlling micturition are controlled by the autonomic and somatic nervous systems. During the storage phase, the internal urethral sphincter remains tense and the detrusor muscle relaxed by sympathetic stimulation. During micturition, parasympathetic stimulation causes the detrusor muscle to contract and the internal urethral sphincter to relax. The external urethral sphincter (sphincter urethrae) is under somatic control and is consciously relaxed during micturition.

In infants, voiding occurs involuntarily (as a reflex). The ability to voluntarily inhibit micturition develops by the age of two–three years, as control at higher levels of the central nervous system develops. In the adult, the volume of urine in the bladder that normally initiates a reflex contraction is about 300–400 millilitres (11–14 imp fl oz; 10–14 US fl oz).

Storage phase

[edit]During storage, bladder pressure stays low, because of the bladder's highly compliant nature. A plot of bladder (intravesical) pressure against the depressant of fluid in the bladder (called a cystometrogram), will show a very slight rise as the bladder is filled. This phenomenon is a manifestation of the law of Laplace, which states that the pressure in a spherical viscus is equal to twice the wall tension divided by the radius. In the case of the bladder, the tension increases as the organ fills, but so does the radius. Therefore, the pressure increase is slight until the organ is relatively full. The bladder's smooth muscle has some inherent contractile activity; however, when its nerve supply is intact, stretch receptors in the bladder wall initiate a reflex contraction that has a lower threshold than the inherent contractile response of the muscle.

Action potentials carried by sensory neurons from stretch receptors in the urinary bladder wall travel to the sacral segments of the spinal cord through the pelvic nerves.[16] Since bladder wall stretch is low during the storage phase, these afferent neurons fire at low frequencies. Low-frequency afferent signals cause relaxation of the bladder by inhibiting sacral parasympathetic preganglionic neurons and exciting lumbar sympathetic preganglionic neurons. Conversely, afferent input causes contraction of the sphincter through excitation of Onuf's nucleus, and contraction of the bladder neck and urethra through excitation of the sympathetic preganglionic neurons.

Diuresis (production of urine by the kidney) occurs constantly, and as the bladder becomes full, afferent firing increases, yet the micturition reflex can be voluntarily inhibited until it is appropriate to begin voiding.

Voiding phase

[edit]Voiding begins when a voluntary signal is sent from the brain to begin urination, and continues until the bladder is empty.

Bladder afferent signals ascend the spinal cord to the periaqueductal gray, where they project both to the pontine micturition center and to the cerebrum.[18] At a certain level of afferent activity, the conscious urge to void or urination urgency, becomes difficult to ignore. Once the voluntary signal to begin voiding has been issued, neurons in the pontine micturition center fire maximally, causing excitation of sacral preganglionic neurons. The firing of these neurons causes the wall of the bladder to contract; as a result, a sudden, sharp rise in intravesical pressure occurs. The pontine micturition center also causes inhibition of Onuf's nucleus, resulting in relaxation of the external urinary sphincter.[19] When the external urinary sphincter is relaxed urine is released from the urinary bladder when the pressure there is great enough to force urine to flow out of the urethra. The micturition reflex normally produces a series of contractions of the urinary bladder.

The flow of urine through the urethra has an overall excitatory role in micturition, which helps sustain voiding until the bladder is empty.[20]

Many men, and some women, may sometimes briefly shiver after or during urination.[21]

After urination, the female urethra empties partially by gravity, with assistance from muscles.[clarification needed] Urine remaining in the male urethra is expelled by several contractions of the bulbospongiosus muscle, and, by some men, manual squeezing along the length of the penis to expel the rest of the urine.

For land mammals over 1 kilogram, the duration of urination does not vary with body mass, being dispersed around an average of 21 seconds (standard deviation 13 seconds), despite a 4 order of magnitude (1000×) difference in bladder volume.[22][23] This is due to increased urethra length of large animals, which amplifies gravitational force (hence flow rate), and increased urethra width, which increases flow rate. For smaller mammals a different phenomenon occurs, where urine is discharged as droplets, and urination in smaller mammals, such as mice and rats, can occur in less than a second.[23] The posited benefits of faster voiding are decreased risk of predation (while voiding) and decreased risk of urinary tract infection.

Voluntary control

[edit]The mechanism by which voluntary urination is initiated remains unsettled.[24] One possibility is that the voluntary relaxation of the muscles of the pelvic floor causes a sufficient downward tug on the detrusor muscle to initiate its contraction.[25] Another possibility is the excitation or disinhibition of neurons in the pontine micturition center, which causes concurrent contraction of the bladder and relaxation of the sphincter.[16]

There is an inhibitory area for micturition in the midbrain. After transection of the brain stem just above the pons, the threshold is lowered and less bladder filling is required to trigger it, whereas after transection at the top of the midbrain, the threshold for the reflex is essentially normal. There is another facilitatory area in the posterior hypothalamus. In humans with lesions in the superior frontal gyrus, the desire to urinate is reduced and there is also difficulty in stopping micturition once it has commenced. However, stimulation experiments in animals indicate that other cortical areas also affect the process.

The bladder can be made to contract by voluntary facilitation of the spinal voiding reflex when it contains only a few milliliters of urine. Voluntary contraction of the abdominal muscles aids the expulsion of urine by increasing the pressure applied to the urinary bladder wall, but voiding can be initiated without straining even when the bladder is nearly empty. Voiding can also be consciously interrupted once it has begun, through a contraction of the perineal muscles. The external sphincter can be contracted voluntarily, which will prevent urine from passing down the urethra.

Experience of urination

[edit]The need to urinate is experienced as an uncomfortable, full feeling. It is highly correlated with the fullness of the bladder.[26] In many males the feeling of the need to urinate can be sensed at the base of the penis as well as the bladder, even though the neural activity associated with a full bladder comes from the bladder itself, and can be felt there as well. In females the need to urinate is felt in the lower abdomen region when the bladder is full. When the bladder becomes too full, the sphincter muscles will involuntarily relax, allowing urine to pass from the bladder. Release of urine is experienced as a lessening of the discomfort.

Disorders

[edit]

Clinical conditions

[edit]Many clinical conditions or urologic diseases can cause disturbances to normal urination, including:

- Urinary incontinence, the inability to hold urine

- Stress incontinence, incontinence as a result of external mechanical disturbances

- Urge incontinence, incontinence that occurs as a result of the uncontrollable urge to urinate

- Mixed incontinence, a combination of the two types of incontinence

- Urinary retention, the inability to initiate urination

- Overactive bladder, a strong urge to urinate, usually accompanied by detrusor overactivity

- Interstitial cystitis, a condition characterized by urinary frequency, urgency, and pain

- Prostatitis, an inflammation of the prostate gland that can cause urinary frequency, urgency, and pain

- Benign prostatic hyperplasia, an enlargement of the prostate that can cause urinary frequency, urgency, retention, and the dribbling of urine

- Urinary tract infection, which can cause urinary frequency and dysuria

- Polyuria, abnormally large production of urine, associated with, in particular, diabetes mellitus (types 1 and 2), and diabetes insipidus

- Oliguria, low urine output, usually due to a problem with the upper urinary tract

- Anuria refers to absent or almost absent urine output.

- Micturition syncope, a vasovagal response which may cause fainting.

- Paruresis, the inability to urinate in the presence of others, such as in a public toilet.

- Bladder sphincter dyssynergia, a discoordination between the bladder and external urethral sphincter as a result of brain or spinal cord injury

A drug that increases urination is called a diuretic, whereas antidiuretics decrease the production of urine by the kidneys.

Experimentally induced disorders

[edit]There are three major types of bladder dysfunction due to neural lesions: (1) the type due to interruption of the afferent nerves from the bladder; (2) the type due to interruption of both afferent and efferent nerves; and (3) the type due to interruption of facilitatory and inhibitory pathways descending from the brain. In all three types the bladder contracts, but the contractions are generally not sufficient to empty the viscus completely, and residual urine is left in the bladder. Paruresis, also known as shy bladder syndrome, is an example of a bladder interruption from the brain that often causes total interruption until the person has left a public area. These people (males) may have difficulty urinating in the presence of others and will consequently avoid using urinals without dividers or those directly adjacent to another person. Alternatively, they may opt for the privacy of a stall or simply avoid public toilets altogether.

Deafferentation

[edit]When the sacral dorsal roots are cut in experimental animals or interrupted by diseases of the dorsal roots such as tabes dorsalis in humans, all reflex contractions of the bladder are abolished. The bladder becomes distended, thin-walled, and hypotonic, but there are some contractions because of the intrinsic response of the smooth muscle to stretch.

Denervation

[edit]When the afferent and efferent nerves are both destroyed, as they may be by tumors of the cauda equina or filum terminale, the bladder is flaccid and distended for a while. Gradually, however, the muscle of the "decentralized bladder" becomes active, with many contraction waves that expel dribbles of urine out of the urethra. The bladder becomes shrunken and the bladder wall hypertrophied. The reason for the difference between the small, hypertrophic bladder seen in this condition and the distended, hypotonic bladder seen when only the afferent nerves are interrupted is not known. The hyperactive state in the former condition suggests the development of denervation hypersensitization even though the neurons interrupted are preganglionic rather than postganglionic.

Spinal cord injury

[edit]During spinal shock, the bladder is flaccid and unresponsive. It becomes overfilled, and urine dribbles through the sphincters (overflow incontinence). After spinal shock has passed, a spinally mediated voiding reflex ensues, although there is no voluntary control and no inhibition or facilitation from higher centers. Some paraplegic patients train themselves to initiate voiding by pinching or stroking their thighs, provoking a mild mass reflex. In some instances, the voiding reflex becomes hyperactive. Bladder capacity is reduced and the wall becomes hypertrophied. This type of bladder is sometimes called the spastic neurogenic bladder. The reflex hyperactivity is made worse, and may be caused, by infection in the bladder wall.

Techniques

[edit]Young children

[edit]A common technique used in many developing nations involves holding the child by the backs of the thighs, above the ground, facing outward, in order to urinate.[citation needed]

Fetal urination

[edit]The fetus urinates hourly and produces most of the amniotic fluid in the second and third trimester of pregnancy. The amniotic fluid is then recycled by fetal swallowing.[27]

Urination after injury

[edit]Occasionally, if a male's penis is damaged or removed, or a female's genitals/urinary tract is damaged, other urination techniques must be used. Most often in such cases, doctors will reposition the urethra to a location where urination can still be accomplished, usually in a position that would promote urination only while seated/squatting, though a permanent urinary catheter may be used in rare cases.[citation needed]

Alternative urination tools

[edit]Sometimes urination is done in a container such as a bottle, urinal, bedpan, or chamber pot (also known as a gazunder). A container or wearable urine collection device may be used so that the urine can be examined for medical reasons or for a drug test, for a bedridden patient, when no toilet is available, or there is no other possibility to dispose of the urine immediately.

An alternative solution (for traveling, stakeouts, etc.) is a special disposable bag containing absorbent material that solidifies the urine within seconds, making it convenient and safe to store and dispose of later.[citation needed]

It is possible for both sexes to urinate into bottles in case of emergencies. The technique can help children to urinate discreetly inside cars and in other places without being seen by others.[28] A female urination device can assist women and girls in urinating while standing or into a bottle.[29]

In microgravity, excrement tends to float freely, so astronauts use a specially designed space toilet, which uses suction to collect and recycle urine; the space toilet also has a receptacle for defecation.[30]

Social and cultural aspects

[edit]Art

[edit]A puer mingens[31] is a figure in a work of art depicted as a prepubescent boy in the act of urinating, either actual or simulated. The puer mingens could represent anything from whimsy and boyish innocence to erotic symbols of virility and masculine bravado.[32]

-

Lapis lynxurius in a medieval bestiary

-

Urinating dog statue at the Château de Fontainebleau

-

Het Zinneke in Brussels

-

Painting of a ram by Abraham Teerlink

-

Ein stallender Schimmel mit einem Bauern, der einen Sattel aufhängt by Francesco Casanova

-

Paard in een weiland dat aan een hek gebonden is by Wouter Johannes van Troostwijk

Toilet training

[edit]Babies have little socialized control over urination within traditions or families that do not practice elimination communication and instead use diapers. Toilet training is the process of learning to restrict urination to socially approved times and situations. Consequently, young children sometimes develop nocturnal enuresis.[33][full citation needed]

Facilities

[edit]It is socially more accepted and more environmentally hygienic for those who are able, especially when indoors and in outdoor urban or suburban areas, to urinate in a toilet. Public toilets may have urinals, usually for males, although female urinals exist, designed to be used in various ways.[34]

Urination without facilities

[edit]

Acceptability of outdoor urination in a public place other than at a public urinal varies with the situation and with customs. Potential disadvantages include a dislike of the smell of urine, and exposure of genitals.[36] It can be avoided or mitigated by going to a quiet place and/or facing a tree or wall if urinating standing up, or while squatting, hiding the back behind walls, bushes, or a tree.[citation needed]

Portable toilets (port-a-potties) are frequently placed in outdoor situations where no immediate facility is available. These need to be serviced (cleaned out) on a regular basis. Urination in a heavily wooded area is generally harmless, actually saves water, and may be condoned for males (and less commonly, females) in certain situations as long as common sense is used. Examples (depending on circumstances) include activities such as camping, hiking, delivery driving, cross country running, rural fishing, amateur baseball, golf, etc.

The more developed and crowded a place is, the more public urination tends to be objectionable. In the countryside, it is more acceptable than in a street in a town, where it may be a common transgression. Often this is done after the consumption of alcoholic beverages, which causes production of additional urine as well as a reduction of inhibitions. One proposed way to inhibit public urination due to drunkenness is the Urilift, which is disguised as a normal manhole by day but raises out of the ground at night to provide a public restroom for bar-goers.

In many places, public urination is punishable by fines, though attitudes vary widely by country. In general, females are less likely to urinate in public than males. Women and girls, unlike men and boys, are restricted in where they can urinate conveniently and discreetly.[37]

The 5th-century BC historian Herodotus, writing on the culture of the ancient Persians and highlighting the differences with those of the Greeks, noted that to urinate in the presence of others was prohibited among Persians.[38][39]

There was[when?] a popular belief in the UK, that it was legal for a man to urinate in public so long as it occurred on the rear wheel of his vehicle and he had his right hand on the vehicle, but this is not true.[40] Public urination still remains more accepted by males in the UK, although British cultural tradition itself seems to find such practices objectionable.[41]

In Islamic toilet etiquette, it is haram to urinate while facing the Qibla, or to turn one's back to it when urinating or relieving bowels, but modesty requirements for females make it impossible for girls to relieve themselves without facilities.[42][43] When toilets are unavailable, females can relieve themselves in Laos, Russia and Mongolia in emergency,[citation needed] but it remains less accepted for females in India even when circumstances make this a highly desirable option.[44]

Women generally need to urinate more frequently than men, but as opposed to the common misconception, it is not due to having smaller bladders.[45] Resisting the urge to urinate because of lack of facilities can promote urinary tract infections which can lead to more serious infections and, in rare situations, can cause renal damage in women.[46][47] Female urination devices are available to help women to urinate discreetly, as well to help them urinate while standing.

Sitting, standing, or squatting

[edit]Techniques and body postures while urinating vary across cultures. Different anatomical conditions in men and women may presume different postures, yet these are largely shaped by cultural norms, types of clothing, and the sanitary facilities available. While sitting toilets are the most common form in Western countries, squat toilets are common in Asia, Africa, and the Arab world. Urinals for men are widespread worldwide, although women's urinals are available in some countries, recently becoming more common in Western countries. With the spread of pants among women, a standing posture became impractical, but in some regions where women wear traditional skirts or robes, an upright posture is common.[48][49]

Some squat as it is the natural posture in which the body aligns the bladder properly and gravity helps to completely empty the bladder which prevents various complications like UTI,[50] which is gender neutral.

Males

[edit]Cultures around the world differ regarding socially accepted voiding positions and preferences: in the Middle East and Asia, the squatting position was more prevalent, while in the Western world the standing and sitting positions were more common.[51] For practising Muslim men, the genital modesty of squatting is also associated with proper cleanliness requirements or awrah.[52] In Western culture, the standing position is regarded as the more efficient or masculine option for healthy males.[53][54] In restrooms without urinals, and sometimes at home, men may be urged to use the sitting position as to diminish spattering of urine.[51]

Elderly males with prostate gland enlargement may benefit from sitting down to urinate, with the seated voiding position found superior as compared with standing in elderly males with benign prostate hyperplasia.[53][55]

In Germany, the practice of men urinating while sitting was promoted in the 1990s, primarily for hygienic reasons.[56][57][58] While urine is sterile, the residue could potentially be colonized by E. coli.[59] In 2014, urologists at the Leiden University Medical Center in the Netherlands published a study stating that sitting is the better position for urination, even for men with prostate enlargement problems.[60][61] Urologist Wolfgang Bührmann noted in 2017 that younger generations were increasingly willing to sit down, attributing this to changing gender roles, with men doing more cleaning of the bathroom.[62] According to a 2023 study by the British market research company YouGov, Germany has the highest proportion of men (over 55 years old) who sit down to urinate. In this study, 40% of German men reported always sitting down, with Sweden following in second place with 22%.[63][64] A survey in Japan from 2020 found that 70% of Japanese men urinate sitting down, up from 51% five years earlier.[60][65] Among married men, the proportion was higher than among unmarried men.[66]

Females

[edit]In Western culture, females usually sit or squat for urination, depending on what type of toilet they use; a squat toilet is used for urination in a squatting position. Women averting contact with a toilet seat may employ a partial squatting position (or "hovering"), similar to using a female urinal. However, this may not completely void the bladder.[67]

Females may also urinate while standing, and while clothed.[34] It is common for women in various regions of Africa to use this position when they urinate,[68][69] as do women in Laos.[70] Herodotus described a similar custom in ancient Egypt.[71] An alternative method for women voiding while standing is to use a female urination device to assist.[72]

Talking about urination

[edit]In many societies and in many social classes, even mentioning the need to urinate is seen as a social transgression, despite it being a universal need. Many adults avoid stating that they need to urinate.[73][74]

Many expressions exist, some euphemistic and some vulgar. For example, centuries ago the standard English word (both noun and verb, for the product and the activity) was "piss", but subsequently "pee", formerly associated with children, has become more common in general public speech. Since elimination of bodily wastes is, of necessity, a subject talked about with toddlers during toilet training, other expressions considered suitable for use by and with children exist, and some continue to be used by adults, e.g. "weeing", "doing/having a wee-wee", "to tinkle", "go potty", "go pee pee".[citation needed]

Other expressions include "squirting" and "taking a leak", and, predominantly by younger persons for outdoor female urination, "popping a squat", referring to the position many women adopt in such circumstances. National varieties of English show creativity. American English uses "to whiz".[75] Australian English has coined "I am off to take a Chinese singing lesson", derived from the tinkling sound of urination against the China porcelain of a toilet bowl.[76] British English uses "going to see my aunt", "going to see a man about a dog", "to piddle", "to splash (one's) boots", as well as "to have a slash", which originates from the Scottish term for a large splash of liquid.[77] One of the most common, albeit old-fashioned, euphemisms in British English is "to spend a penny", a reference to coin-operated pay toilets, which used (pre-decimalisation) to charge that sum.[78]

Use in language

[edit]References to urination are commonly used in slang. Usage in English includes:

- Piss (someone) off (to anger someone; alternatively, to leave somewhere in a hurry)

- Piss off! (to express contempt; see above)

- Pissing down (to refer to heavy rain)

- Pissing contest (an unproductive ego-driven battle)

- Pisshead (vulgar way to refer to someone who drinks too much alcohol)

- Piss ant (a worthless person; in non-slang usage the term refers to several species of ant whose colonies have a urine-like odor)

- Pissing up a flagpole (to partake in a futile activity)

- Pissing into the wind (to act in ways that cause self-harm)

- Piss away (to squander or use wastefully)

- Taking the piss (to take liberties, be unreasonable, or to mock another person)

- Full of piss and vinegar (energetic or ambitious late adolescent or young adult male)

- Piss up (British expression for drinking to get drunk)

- Pissed (drunk in British English or angry in American English)

Urination and sexual activity

[edit]In humans

[edit]

In human males, the internal urethral sphincter usually contracts during orgasm in order to prevent urination or retrograde ejaculation.[80]

Urolagnia is a paraphilia related to the act, sight, or smell of urine or urination.[81] Urine may be consumed, or the person may bathe in it; this is known colloquially as a golden shower. Involuntary urination during sexual intercourse is common, but rarely acknowledged. In one survey, 24% of women reported involuntary urination during sexual intercourse; in 66% of patients urination occurred on penetration, while in 33% urine leakage was restricted to orgasm.[82]

In other animals

[edit]Female kob may exhibit urolagnia during sex; one female will urinate while the other sticks her nose in the stream.[83][84]

Some mammals urinate on themselves in order to attract mates during the rut or urinate on other individuals before mating with them.[85] A male Patagonian mara, a type of rodent, will stand on his hind legs and urinate on a female's rump, to which the female may respond by spraying a jet of urine backwards into the face of the male.[86] The male's urination is meant to repel other males from his partner while the female's urination is a rejection of any approaching male when she is not receptive.[86] Both anal digging and urination are more frequent during the breeding season and are more commonly done by males.[87]

A male porcupine urinates on a female porcupine prior to mating, spraying the urine at high velocity.[88][89][90][91][92]

Electric shock injuries and deaths

[edit]In 2008 in London, a person died when they were urinating alongside a railway track at a train station and they received an electric shock.[93][94] The person received the electric shock when their stream of urine connected with the electric current from the live third rail.[93]

In 2010 in Washington state, a person who had died had received burns injuries on their body that were related to receiving an electric shock.[95] It is thought that an electric current had traveled through their stream of urine and into their body.[95] It is thought that the person had urinated into a roadside ditch and a live wire that was lying in the ditch gave the person an electric shock.[95]

In 2014 in Spain, a person died while urinating on a lamp post when he received an electric shock, which may have traveled through the stream of urine and into his body.[96]

Other species

[edit]While the primary purpose of urination is the same across the animal kingdom, urination often serves a social purpose beyond the expulsion of waste material.[97][98] In dogs and other animals, urination can mark territory or express submissiveness.[79] In small rodents such as rats and mice, it marks familiar paths.

The urine of animals of differing physiology or sex sometimes has different characteristics. For example, the urine of birds and reptiles is whitish, consisting of a pastelike suspension of uric acid crystals, and discharged with the feces of the animal via the cloaca, whereas mammals' urine is a yellowish colour, with mostly urea instead of uric acid, and is discharged via the urethra, separately from the feces. Some animals' (example: carnivores') urine possesses a strong odour, especially when it is used to mark territory or communicate in other ways.[clarify][citation needed]

Felids[12][99][100] and canids[14][101] scent-mark their territories using urine. Wolves mark their territories by urinating in a raised-leg posture and release preputial gland secretions in their urine. Male dogs mark their territories with urine more frequently than females.[14]

Young cattle can be toilet-trained to urinate in a "latrine" where their urine can be collected for wastewater treatment,[102][103] which could be used to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from the animals' urine in countries such as the Netherlands, the United States, and New Zealand.[104]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Marvalee H. Wake (15 September 1992). Hyman's Comparative Vertebrate Anatomy. University of Chicago Press. p. 583. ISBN 978-0-226-87013-7. Retrieved 6 May 2013.

- ^ Roughgarden J (2004). Evolution's Rainbow: Diversity, Gender, and Sexuality in Nature and People. University of California Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-520-24073-5. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- ^ Feder ME, Burggren WW (15 October 1992). Environmental Physiology of the Amphibians. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-23944-6.

- ^ Fry C (July 2006). "Micturition". Anaesthesia & Intensive Care Medicine. 7 (7): 237–239. doi:10.1053/j.mpaic.2006.04.006.

- ^ Gormley EA, Lightner DJ, Burgio KL, Chai TC, Clemens JQ, Culkin DJ, Das AK, Foster HE, Scarpero HM, Tessier CD, Vasavada SP (December 2012). "Diagnosis and Treatment of Overactive Bladder (Non-Neurogenic) in Adults: AUA/SUFU Guideline". Journal of Urology. 188 (6S): 2455–2463. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2012.09.079. PMID 23098785.

- ^ Heidi K. Wennemer (7 July 2008). "Urinary Incontinence – Part 2". United States Department of Veterans Affairs. Archived from the original on 25 September 2008. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ^ Rajaofetra N, Passagia JG, Marlier L, Poulat P, Pellas F, Sandillon F, Verschuere B, Gouy D, Geffard M, Privat A (1992). "Serotoninergic, noradrenergic, and peptidergic innervation of Onuf's nucleus of normal and transected spinal cords of baboons (Papio papio)". J. Comp. Neurol. 318 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1002/cne.903180102. PMID 1374763. S2CID 23190313.(subscription required)

- ^ Müller-Schwarze, Dietland. "Pheromones in black-tailed deer (Odocoileus hemionus columbianus)." Animal Behaviour 19.1 (1971): 141–152.

- ^ Moore, W. GERALD, and R. LARRY Marchinton. "Marking behavior and its social function in white-tailed deer." The behaviour of ungulates and its relation to management 1 (1974): 447–456.

- ^ Lincoln GA (1971). "The seasonal reproductive changes in the red deer stag (Cervus elaphus)". Journal of Zoology. 163 (1): 105–123. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1971.tb04527.x.

- ^ Yang PJ, Pham J, Choo J, Hu DL (19 August 2014). "Duration of urination does not change with body size". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (33): 11932–11937. Bibcode:2014PNAS..11111932Y. doi:10.1073/pnas.1402289111. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 4143032. PMID 24969420.

- ^ a b Schulz S (7 January 2005). The Chemistry of Pheromones and Other Semiochemicals II. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-540-21308-6.

- ^ Asa, Cheryl S. "Relative contributions of urine and anal-sac secretions in scent marks of large felids." American Zoologist 33.2 (1993): 167-172.

- ^ a b c L. David Mech, Luigi Boitani (1 October 2010). Wolves: Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation. University of Chicago Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-226-51698-1. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- ^ Spotte S (15 March 2012). Societies of Wolves and Free-ranging Dogs. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-37910-7.

- ^ a b c d e Yoshimura N, Chancellor MB (2003). "Neurophysiology of Lower Urinary Tract Function and Dysfunction". Rev Urol. 5 (Suppl 8): S3 – S10. PMC 1502389. PMID 16985987.

- ^ de Groat WC, Ryall RW (January 1969). "Reflexes to sacral parasympathetic neurones concerned with micturition in the cat". J. Physiol. 200 (1): 87–108. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1969.sp008683. PMC 1350419. PMID 5248885.

- ^ Blok BF, Holstege G (January 1994). "Direct projections from the periaqueductal gray to the pontine micturition center (M-region). An anterograde and retrograde tracing study in the cat". Neurosci. Lett. 166 (1): 93–6. doi:10.1016/0304-3940(94)90848-6. PMID 7514777. S2CID 41146134.

- ^ Sie JA, Blok BF, de Weerd H, Holstege G (2001). "Ultrastructural evidence for direct projections from the pontine micturition center to glycine-immunoreactive neurons in the sacral dorsal gray commissure in the cat". J. Comp. Neurol. 429 (4): 631–7. doi:10.1002/1096-9861(20010122)429:4<631::AID-CNE9>3.0.CO;2-M. PMID 11135240. S2CID 7570375.

- ^ Jung SY, Fraser MO, Ozawa H, Yokoyama O, Yoshiyama M, De Groat WC, Chancellor MB (July 1999). "Urethral afferent nerve activity affects the micturition reflex; implication for the relationship between stress incontinence and detrusor instability". Journal of Urology. 162 (1): 204–212. doi:10.1097/00005392-199907000-00069. PMID 10379788.

- ^ Briggs B (9 April 2012). "Pee shivers: You know you're curious". NBC News.

- ^ Yang PJ, Pham JC, Choo J, Hu DL (2013). "Law of Urination: all mammals empty their bladders over the same duration". arXiv:1310.3737 [physics].

- ^ a b Arnold C (23 October 2013). "New Law of Urination: Mammals Take 20 Seconds to Pee". National Geographic.

- ^ DasGupta R, Kavia RB, Fowler CJ (2007). "Cerebral mechanisms and voiding function". BJU Int. 99 (4): 731–4. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.06749.x. PMID 17378838. S2CID 12318860.

- ^ Kinder M, Bastiaanssen E, Janknegt R, Marani E (September 1995). "Neuronal circuitry of the lower urinary tract; central and peripheral neuronal control of the micturition cycle". Anatomy and Embryology. 192 (3): 195–209. doi:10.1007/BF00184744. PMID 8651504.

- ^ Oliver S, Fowler C, Mundy A, Craggs M (2003). "Measuring the sensations of urge and bladder filling during cystometry in urge incontinence and the effects of neuromodulation". Neurourol. Urodyn. 22 (1): 7–16. doi:10.1002/nau.10082. PMID 12478595. S2CID 37724763.

- ^ Underwood MA, Gilbert WM, Sherman MP (2005). "Amniotic Fluid: Not Just Fetal Urine Anymore". Journal of Perinatology. 25 (5): 341–348. doi:10.1038/sj.jp.7211290. PMID 15861199.

- ^ Maloney L (5 January 2019). "Can I Pee in a Bottle If I'm Stuck in a Tent?". TripSavvy. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ "The Complete Guide to Female Urination Devices". Backpacker. 10 September 2015. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ Elburn D (2 August 2019). "Boldly Go! NASA's New Space Toilet". NASA. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Piepenbring D (20 September 2017). "A secret history of the pissing figure in art". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ Simons P (2009). "Manliness and the Visual Semiotics of Bodily Fluids in Early Modern Culture". Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies. 39 (2): 331–373. doi:10.1215/10829636-2008-025.

- ^ Review of Medical Physiology, twentieth edition, William F. Ganong, MD

- ^ a b "A Woman's Guide on How to Pee Standing". Archived from the original on 4 June 2003.

- ^ Kögel E (2015), The Grand Documentation: Ernst Boerschmann and Chinese Religious Architecture (1906–1931), Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, p. 161, ISBN 978-3-11-040134-9.

- ^ Saner E (5 April 2023). "The war against wild toileting: is there any way to stop people weeing – and worse – in the street?". UK: Guardian. Retrieved 19 March 2024.

- ^ The new ourselves, growing older: women aging with knowledge and power, Paula Brown Doress-Worters, Diana Laskin Siegal, Boston Women's Health Book Collective, Simon & Schuster, 1994, Page 301

- ^ electricpulp.com. "HERODOTUS iii. DEFINING THE PERSIANS – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org.

- ^ "Internet History Sourcebooks". sourcebooks.fordham.edu.

- ^ "Legal Curiosities: Fact or Fable?" (PDF). Law Commission (England and Wales). April 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 June 2015.

- ^ "From buttoned-up Britain to urine nation". New Statesman. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- ^ Unveiling the Breath: One Woman's Journey Into Understanding Islam and Gender Equality, Donna Kennedy-Glans pg. 69

- ^ Rizvi SS (1986). Elements of Islamic Studies. Bilal Muslim Mission of Tanzania. ISBN 978-9976-956-05-4.[page needed]

- ^ Schwarzenbach SA, Smith P (2004). Women and the U.S. Constitution: History, Interpretation, and Practice. Columbia University Press. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-231-50296-2.

- ^ "Report of the Task Group on Reference Man". Report of the Task Group on Reference Man. Pergamon Press: 180. 1975.

- ^ "06/07/2002 - Mobile crews must have prompt access to nearby toilet facilities". Osha.gov. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ^ "Urinary Tract Infection (UTI) Prevention – Urinary Tract Infection (UTI)". Urologychannel.com. Archived from the original on 3 February 2011. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ^ B. Möllring (2003): Toiletten und Urinale für Frauen und Männer: die Gestaltung von Sanitärobjekten und ihre Verwendung in öffentlichen und privaten Bereichen. Publication of the Berlin University of the Arts (German)

- ^ Gershenson O, Penner B (2009). Ladies and Gents: Public Toilets and Gender. Temple University Press. ISBN 978-1-59213-940-8.[page needed]

- ^ "How to Prevent a UTI Naturally". 18 March 2021.

- ^ a b de Jong Y, Pinckaers J, ten Brinck R, Lycklama à Nijeholt A (February 2014). "Invloed van mictiehouding op urodynamische parameters bij mannen: een literatuuronderzoek" [Influence of voiding posture on urodynamic parameters in men: a literature review]. Tijdschrift voor Urologie (in Dutch). 4 (1): 36–42. doi:10.1007/s13629-014-0008-5.

- ^ Mustafa Umar. "Standing up and urinating in Islam". Iman Suhaib Webb (USA). Archived from the original on 30 May 2013. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- ^ a b Phelps C, Moro C (16 June 2023). "Does it matter if you sit or stand to pee? And what about peeing in the shower?". The Conversation. Retrieved 3 March 2025.

- ^ "Guys Who Sit Down to Pee: Why?". VICE. 27 October 2023. Retrieved 3 March 2025.

- ^ de Jong Y, Pinckaers JH, Ten Brinck RM, Lycklama À Nijeholt AA, Dekkers OM (2014). "Urinating Standing versus Sitting: Position Is of Influence in Men with Prostate Enlargement. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". PLOS ONE. 9 (7) e101320. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j1320D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0101320. PMC 4106761. PMID 25051345.

- ^ Albert Hauser: Das Sitzpinkel-Manifest. Hier sitzt Mann. Eichborn Verlag, Frankfurt am Main, 1997, ISBN 9783821830506.

- ^ Bettina Möllring: Toiletten und Urinale für Frauen und Männer – die Gestaltung von Sanitärobjekten und ihre Verwendung in öffentlichen und privaten Bereichen. Dissertation, Universität der Künste Berlin, 2003, S. 22

- ^ Lisa Ortgies, Svea Große: Pinkeln im Stau und andere Katastrophen. Der Survivalguide für Frauen. vgs Verlagsgesellschaft, 2003, ISBN 3-8025-1505-6

- ^ Tadd Truscott; Randy Hurt: Urinal Dynamics: A Tactical Summary. 2013

- ^ a b The Splashback Scandal: Should All Men Sit Down to Urinate? The Guardian, 20. Februar 2023

- ^ de Jong Y, Pinckaers JHFM, ten Brinck RM, Lycklama a` Nijeholt AAB, Dekkers OM: Urinating Standing versus Sitting: Position Is of Influence in Men with Prostate Enlargement. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 9(7)

- ^ Männer, wir haben bei der Sitzpinkel-Debatte ein wichtiges Detail übersehen. Die Zeit, 15. August 2017

- ^ Deutsche Männer sind Sitzpinkler. Yougov.de, 22. Mai 2023

- ^ Deutsche sind die größten Sitzpinkler. Frankfurter Allgemeine, 17. Mai 2023

- ^ Give Pee a Chance: Why German Men Urinate Sitting Down. bigthink.com, 24. März 2023

- ^ Sekido N, Haga N, Omae K, Kubota Y, Mitsui T, Masumori N, Saito M, Sakakibara R, Yoshida M, Takahashi S (2025). "Is seated voiding associated with lower urinary tract symptoms, health conditions, or marital status? Findings by age group from the 2023 Japan Community Health Survey". International Journal of Urology. 32 (2): 204–211. doi:10.1111/iju.15624. PMC 11803177. PMID 39451098.

- ^ "Preventing kidney infection". nhs.uk. National Health Service. 11 December 2012. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ^ "Courtesy Laughs in the Ivory Coast". Travelblog.org. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ^ "Women Standing and Men Squatting to Pee – A Personal Story (Mobile Version)". Experienceproject.com. Archived from the original on 29 July 2013.

- ^ "Road to Hanoi". Travelblog.org. 16 November 2005. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ^ Rothstein E (10 December 2007). "Herodotus – The Histories – Connections". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 January 2010.

- ^ "Women Can 'Go' Like Men Now!". Archived from the original on 11 October 2009. Retrieved 11 October 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link), ABC 2 News, Maryland, 3 September 2009 - ^ "excuse yourself to go to the toilet politely - English Vocabulary - English - The Free Dictionary Language Forums". forum.thefreedictionary.com.

- ^ "Is there a formal way to say we want to go to the toilet?". english.stackexchange.com.

- ^ "Definition of WHIZ". www.merriam-webster.com. 17 March 2024.

- ^ "have Chinese singing lesson". Definition-of.com. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ^ "have a slash – Dictionary of sexual terms". Sex-lexis.com. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ^ Martin G. "Spend a penny". Phrases.org.uk. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ^ a b Richard Estes (1991). The Behavior Guide to African Mammals: Including Hoofed Mammals, Carnivores, Primates. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-08085-0.

urine.

- ^ "Retrograde ejaculation - MayoClinic.com".

- ^ "Definition of urolagnia". Oxforddictionaries.com. Archived from the original on 9 July 2012. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ^ Hilton P (1988). "Urinary incontinence during sexual intercourse: a common, but rarely volunteered, symptom". BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 95 (4): 377–381. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1988.tb06609.x. PMID 3382610. S2CID 26659249.

- ^ Kick (2001)

- ^ Imaginova (2007e)

- ^ Vandenbergh J (2 December 2012). Pheromones and Reproduction in Mammals. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-323-15651-6.

- ^ a b Genest H., Dubost G. (1974). "Pair living in the mara ( Dolichotis paragonum Z )". Mammalia. 38 (2): 155–162. doi:10.1515/mamm.1974.38.2.155. S2CID 86771537.

- ^ TABER B. E., MACDONALD D. W. (1984). "Scent dispersing papillae and associated behaviour in the mara, Dolichotis patagonum (Rodentia: Caviomorpha)". Journal of Zoology. 203 (2): 298–301. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1984.tb02333.x.

- ^ Charles Fergus (1 September 2000). Wildlife of Pennsylvania: And the Northeast. Stackpole Books. pp. 75–. ISBN 978-0-8117-2899-7. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ^ Uldis Roze (28 September 2012). Porcupines: The Animal Answer Guide. JHU Press. pp. 97–. ISBN 978-1-4214-0735-7. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ^ Marshall Cavendish (2007). EXPLORING MAMMALS. Marshall Cavendish. pp. 1088–. ISBN 978-0-7614-7719-8. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ^ Donna Naughton (2012). A Natural History of Canadian Mammals. University of Toronto Press. pp. 214–. ISBN 978-1-4426-4483-0. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ^ Trevor Carnaby (30 January 2008). Beat About the Bush: Mammals. Jacana Media. ISBN 978-1-77009-240-2. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ^ a b "Polish tourist killed by urinating on 750-volt electric railway line". Evening Standard. 13 April 2012. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ "Urinating on electric track kills man". Nine News (Australia). 23 July 2008. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ a b c "Man electrocuted by urinating on power line". NBC News. 2 March 2010. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- ^ Rkaina S (31 August 2014). "Teenage reveller dies after being electrocuted while URINATING on lamp-post during festival". Irish Mirror. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- ^ Gosling L. M. (1982). "A reassessment of the function of scent marking in territories" (PDF). Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie. 60 (2): 89–118. Bibcode:1982Ethol..60...89G. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.1982.tb00492.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2018.

- ^ Richard Doty (2 December 2012). Mammalian Olfaction, Reproductive Processes, and Behavior. Elsevier Science. ISBN 978-0-323-15450-5.

- ^ Ewer RF (1968). "Scent marking". Ethology of Mammals. pp. 104–133. doi:10.1007/978-1-4899-4656-0_5. ISBN 978-1-4899-4658-4.

- ^ Sunquist M, Sunquist F (15 May 2017). Wild Cats of the World. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-51823-7.

- ^ Henry JD (1977). "The Use of Urine Marking in the Scavenging Behavior of the Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes)". Behaviour. 61 (1–2): 82–105. doi:10.1163/156853977X00496. JSTOR 4533812. PMID 869875.

- ^ Dirksen N, Langbein J, Schrader L, Puppe B, Elliffe D, Siebert K, Röttgen V, Matthews L (September 2021). "Learned control of urinary reflexes in cattle to help reduce greenhouse gas emissions". Current Biology. 31 (17): R1033 – R1034. Bibcode:2021CBio...31R1033D. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2021.07.011. PMID 34520709.

- ^ "Cows toilet trained to reduce greenhouse gas emissions". BBC. 14 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ Hassan J, Pannett R (15 September 2021). "Cow pee is an environmental problem. But now scientists say calves can be potty-trained". Washington Post.

Further reading

[edit]- Mech LD, Boitani L (2003). Wolves: Behaviour, Ecology and Conservation. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-51696-7.

- Young SP, Jackson HH (1978). The Clever Coyote. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-5893-8.

- de Groat WC, Griffiths D, Yoshimura N (17 January 2011). "Neural Control of the Lower Urinary Tract". Comprehensive Physiology. 5 (1): 327–396. doi:10.1002/cphy.c130056. PMC 4480926. PMID 25589273.

External links

[edit]- Neurogenic Bladder at eMedicine, describes the neurophysiology of urination

- "Urination" at HowStuffWorks.com

Urination

View on GrokipediaBiological Foundations

Anatomy of the Urinary Tract

The urinary tract consists of the kidneys, ureters, urinary bladder, and urethra, which collectively produce, transport, temporarily store, and eliminate urine from the body.[4] The kidneys filter approximately 180 liters of plasma daily to form 1-2 liters of urine, removing waste products such as urea and excess ions while maintaining fluid and electrolyte balance.[3] The kidneys are paired, bean-shaped organs located retroperitoneally on either side of the vertebral column, spanning from the 12th thoracic to the 3rd lumbar vertebra.[6] Each kidney measures about 11-14 cm in length, 6 cm in width, and 3 cm in thickness, with an average adult weight of 150 grams.[5] Externally, the kidney is enclosed by a fibrous capsule and surrounded by perirenal fat; internally, it features an outer cortex and inner medulla composed of renal pyramids that drain into calyces converging at the renal pelvis.[3] The ureters are bilateral muscular tubes, approximately 25-30 cm long and 3-4 mm in diameter, extending from the renal pelvis to the bladder.[7] They propel urine via peristaltic contractions at a rate of 1-5 waves per minute, entering the bladder posterolaterally at the ureterovesical junction, where a valve-like mechanism prevents reflux.[7] The urinary bladder is a distensible, muscular sac situated in the pelvic cavity behind the pubic symphysis, with a typical capacity of 400-600 ml in adults.[8] Its wall comprises the detrusor muscle, a layer of smooth muscle that contracts during voiding, lined by transitional epithelium that accommodates expansion without rupture.[8] The bladder's apex points anteriorly, base posteriorly, and it connects superiorly to the ureters and inferiorly to the urethra at the internal urethral orifice. The urethra serves as the final conduit for urine expulsion, differing significantly between sexes due to reproductive anatomy. In females, it measures 3-5 cm in length, extending from the bladder neck to the external meatus anterior to the vaginal opening, lacking prostatic involvement.[9] In males, the urethra is longer at 18-20 cm, divided into prostatic, membranous, and spongy (penile) segments, traversing the prostate gland and penis to facilitate both urination and semen passage.[9] Both urethras feature internal and external sphincters for continence, with the female structure's brevity contributing to higher urinary tract infection susceptibility.[10]Physiology of Storage and Voiding

Urine storage in the bladder occurs through coordinated relaxation of the detrusor smooth muscle and contraction of the urethral sphincters, allowing accommodation of up to approximately 500 mL in healthy adults.[1] Sympathetic innervation from the thoracolumbar spinal cord (T11-L2) via the hypogastric nerves activates β3-adrenergic receptors on detrusor myocytes, increasing cyclic AMP to inhibit contraction and promote relaxation.[11] [12] The internal urethral sphincter maintains tone through α1-adrenergic receptor-mediated contraction induced by norepinephrine release from the same sympathetic fibers.[1] Somatic innervation from Onuf's nucleus (S2-S4) via the pudendal nerve sustains external urethral sphincter contraction through nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, further preventing leakage.[12] Afferent signals from low-threshold Aδ stretch receptors in the bladder wall, transmitted via pelvic and hypogastric nerves, enable sensory awareness of filling; the first sensation of fullness typically arises at 150-250 mL, with maximal capacity around 400-500 mL under normal compliance of 12.5-40 mL/cm H₂O.[1] Spinal guarding reflexes, mediated by interneurons in the sacral cord, enhance sphincter contraction in response to transient pressure increases, such as during coughing or Valsalva maneuvers, to inhibit involuntary voiding.[12] Bladder compliance ensures intravesical pressure remains below 20 cm H₂O during filling, minimizing wall stress and reflux risk.[1] Voiding, or micturition, is initiated when bladder distension activates high-threshold afferents, triggering a spinobulbospinal reflex pathway that engages the pontine micturition center (PMC, or Barrington's nucleus) in the brainstem.[12] The PMC coordinates parasympathetic efferents from the sacral cord (S2-S4) via pelvic nerves, releasing acetylcholine to stimulate M3 muscarinic receptors on detrusor cells, elevating intracellular calcium and generating coordinated contractions that elevate intravesical pressure to 30-40 cm H₂O in males (lower in females).[11] [1] Simultaneously, the PMC inhibits sympathetic outflow and somatic pudendal activity, relaxing the internal sphincter through nitric oxide-mediated smooth muscle inhibition and the external sphincter via reduced excitatory input.[12] Higher cortical centers, including the prefrontal cortex and periaqueductal gray, modulate the PMC to permit voluntary initiation or suppression of voiding once the reflex threshold is reached, integrating sensory input for appropriate timing.[12] Efficient voiding requires detrusor-sphincter synergy, with complete emptying typically leaving post-void residuals under 50 mL in healthy individuals; disruptions in this neural coordination underlie conditions like detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia.[1]Neural and Sensory Mechanisms

The sensory mechanisms of urination primarily involve afferent nerve fibers embedded in the bladder wall and urethra that detect mechanical distension and chemical changes in urine. These include myelinated Aδ fibers, which convey the sensation of bladder filling and first desire to void at volumes around 150-250 mL in adults, and unmyelinated C-fibers, which activate during noxious distension or inflammation to signal urgency or pain.[12][13] These afferents travel via the pelvic nerves to the sacral spinal cord (S2-S4 segments), where they synapse with interneurons to initiate reflex responses.[12] Urethral afferents similarly provide feedback during voiding to ensure complete emptying and prevent overdistension.[14] At the spinal level, micturition operates through a spinobulbospinal reflex arc coordinated by parasympathetic, sympathetic, and somatic efferents. Parasympathetic preganglionic neurons in the sacral cord (S2-S4) release acetylcholine onto postganglionic neurons in the pelvic plexus, stimulating detrusor muscle contraction via muscarinic receptors during voiding; sympathetic input from thoracolumbar segments (T10-L2) promotes storage by relaxing the detrusor through β-adrenergic receptors and contracting the internal urethral sphincter via α-receptors.[12][15] The somatic pudendal nerve (S2-S4) maintains external urethral sphincter tone via cholinergic innervation during storage but relaxes it during voiding to allow urine flow.[14] This reflex is modulated by spinal interneurons that integrate afferent signals, enabling involuntary coordination unless overridden by supraspinal inputs.[12] Supraspinal control is centered in the pontine micturition center (PMC, or Barrington's nucleus) in the brainstem, which receives processed afferent signals via the periaqueductal gray (PAG) and coordinates the switch from storage to voiding by exciting parasympathetic outflow and inhibiting somatic and sympathetic activity.[12][16] The PAG acts as a relay, integrating visceral afferents with inputs from higher cortical areas like the prefrontal cortex, which exerts voluntary inhibitory control to delay urination until socially appropriate.[17] Hypothalamic and cerebellar influences further fine-tune timing and rhythmicity, with disruptions in these pathways—such as in spinal cord injury—leading to detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia where the sphincter fails to relax during detrusor contraction.[18][19] This hierarchical organization ensures efficient storage (up to 400-600 mL capacity) and voiding, with voiding pressures typically 20-40 cm H₂O in healthy adults.[14]Evolutionary and Comparative Perspectives

Evolutionary Origins and Adaptations

The excretory mechanisms underlying urination originated in early metazoans as simple structures for maintaining body fluid homeostasis, such as nephridia in annelids and flame cells in flatworms, which filtered waste via ultrafiltration and selective reabsorption to counter osmotic gradients.[20] These primitive systems expelled nitrogenous wastes continuously or in pulses, without dedicated storage organs, adapting to aquatic environments where ammonia diffusion sufficed due to high water availability.[21] In vertebrates, the urinary system evolved from a common nephric duct shared with reproductive functions, with kidneys progressing through three embryonic stages: the transient pronephros in early embryos, the mesonephros functional in fish and amphibians, and the metanephros as the permanent adult kidney in reptiles, birds, and mammals, enabling more efficient glomerular filtration and tubular reabsorption.[22] The urinary bladder, central to controlled urination, arose independently at least twice in vertebrate lineages, first in lungfish and amphibians for water storage and reabsorption, and separately in amniotes for waste containment.[23] This organ's epithelial lining exhibits variable permeability to water and solutes, allowing amphibians to reabsorb up to 50% of bladder urine osmotically during terrestrial dehydration, a key adaptation for life on land where continuous voiding would lead to desiccation.[23] In mammals, the bladder's smooth muscle layers enable distension to 400-500 ml capacity under low pressure (typically 10-20 cm H₂O), facilitating voluntary micturition via coordinated detrusor contraction and sphincter relaxation, which evolved to reduce constant scent emission and predation risk by minimizing urine trails.[24] Terrestrial adaptations further refined urination for nitrogen conservation, shifting from ammonia in aquatic vertebrates to urea in mammals, with loop of Henle countercurrent multipliers concentrating urine up to 1,200 mOsm/L in humans versus plasma's 300 mOsm/L, preventing excessive water loss.[25] The separation of urinary and cloacal tracts in placental mammals, absent in monotremes and marsupials, permitted rectal absorption of water from urine, enhancing post-renal modification and acid-base regulation amid dietary and environmental shifts.[26] These changes reflect selective pressures from aridity and predation, where intermittent, directed voiding supports territorial signaling via pheromones while conserving resources, as evidenced by higher urinary concentrating ability in desert-adapted species like kangaroo rats (up to 9,000 mOsm/L).[25]Urination Across Species

Urination, the expulsion of urine from the body, exhibits significant variations across species, reflecting adaptations to diverse environments, physiologies, and behaviors. In vertebrates, the process generally involves filtration in kidneys to form urine, storage in a bladder where present, and voiding through a urethra or cloaca. Mammals typically produce urea as the primary nitrogenous waste, enabling efficient water conservation via hyperosmotic urine up to 25 times blood osmolality in some species.[27] Birds and reptiles, being uricotelic, excrete uric acid as a semi-solid paste, minimizing water loss, with urine osmolalities reaching 2-4 times blood levels.[28] Amphibians, ureotelic like mammals, produce urine isoosmotic to blood or slightly hypoosmotic due to permeable skins, while many fish excrete ammonia directly via gills, lacking bladders and relying on diffuse renal output.[29] [30] Mammalian urination follows hydrodynamic principles where voiding duration remains approximately 21 seconds across body sizes from mice to elephants, governed by urethral scaling that balances gravity and flow rates.[31] Bladder capacities scale with body mass, but frequency adjusts to metabolic needs; for instance, desert-adapted mammals like kangaroo rats void minimal volumes of highly concentrated urine (up to 9,000 mOsm/L) to conserve water, featuring elongated loops of Henle for enhanced reabsorption.[32] [33] Postures vary: quadrupeds often adopt squatting or leg-lifting for males to direct streams, aiding territorial marking where urine deposits pheromones to signal dominance or boundaries.[34] In birds, adults lack bladders, with urine produced by metanephric kidneys and voided via the cloaca alongside feces, forming a uric acid suspension that precipitates to reduce liquidity.[28] Reptiles similarly employ cloacal voiding, with uricotelism predominant in terrestrial forms to combat desiccation; aquatic reptiles may shift toward ureotelism.[35] Amphibians void through cloacas or simple ducts, with urine often reabsorbed via bladder epithelia in terrestrial species to maintain hydration.[29] Teleost fish kidneys produce dilute urine continuously without storage, expelling it posteriorly to counter osmotic influx in freshwater or conserve salts in marine environments.[36] Behavioral roles extend beyond excretion in many species, particularly mammals, where urine marking delineates territories, as seen in canids raising legs to spray vertical surfaces for broader scent dispersion detectable by conspecifics.[37] [38] Felids employ spraying for reproductive signaling, with intact individuals depositing small volumes to advertise availability.[39] These functions underscore urine's chemical communication utility, evolved for social and ecological fitness without compromising excretory efficiency.[40]Sex-Specific Biological Differences

The male urethra measures approximately 15-22 cm in length, extending from the bladder through the prostate gland and penis to the external meatus, while the female urethra is significantly shorter at 3-5 cm, connecting the bladder directly to the external orifice above the vaginal opening.[41][42][10] This disparity in urethral length arises from embryonic development, where the male urethra incorporates the penile structure for dual reproductive and excretory functions, whereas the female urethra remains a simpler conduit optimized for urinary expulsion.[42] The prostate gland in males encircles the proximal urethra, influencing voiding dynamics through its glandular secretions and potential for hypertrophy.[43] These anatomical variations manifest in distinct urination physiologies. Males typically achieve higher maximum urinary flow rates, partly attributable to the longer urethral path reducing resistance in a standing position, enabling directed streams with less postural adjustment.[44] In females, the shorter urethra facilitates quicker voiding but results in a more diffuse stream, often requiring a seated posture to minimize splashing and ensure hygiene.[42] Pelvic floor musculature differs sexually, with females exhibiting greater elasticity due to reproductive adaptations, which can affect urethral closure pressure and continence during voiding.[42] Hormonal influences, such as estrogen maintaining mucosal integrity in females and androgens supporting prostate function in males, further modulate urethral tone and bladder outlet resistance.[42] Sex-specific vulnerabilities highlight functional divergences. Females face a markedly higher incidence of urinary tract infections, up to 30 times greater than males before menopause, primarily because the abbreviated urethral length permits easier ascent of uropathogenic bacteria from perineal flora.[45][46] In males, benign prostatic hyperplasia, affecting over 50% by age 60, compresses the urethra, leading to obstructed flow, incomplete emptying, and nocturia as the gland enlarges and impinges on bladder neck dynamics.[47][43] These differences underscore how sexual dimorphism in the lower urinary tract shapes both normative voiding patterns and age-related pathologies.[42]Developmental and Lifespan Variations

Fetal and Neonatal Urination

The development of the fetal urinary system commences with the formation of the nephrogenic cord around the fourth week of gestation, progressing through pronephros, mesonephros, and metanephros stages, with the metanephros—the permanent kidney—beginning urine production by the 10th to 12th week.[48] [49] By the 13th week, functional urine output is established as nephrons mature, though full nephron development completes between 32 and 36 weeks.[50] [51] Fetal urine initially contributes modestly to amniotic fluid but becomes the dominant source after 16-20 weeks, with production rates escalating to approximately 300 mL/kg fetal weight per day, or 600-1200 mL/day near term, aiding in fluid homeostasis through fetal swallowing and intramembranous absorption.[51] [52] Disruptions in this process, such as renal agenesis, result in oligohydramnios, underscoring urination's causal role in fetal lung expansion and musculoskeletal development.[49] In neonates, voiding typically initiates within 24 hours post-birth in healthy term infants, with initial urine possibly containing urate crystals that tint diapers orange or pink due to concentration effects.[53] Urination frequency averages 10-15 episodes per day during the first year, often every 1-3 hours, reflecting a small bladder capacity of about 30-60 mL and high glomerular filtration rates relative to body size.[54] [55] Neonatal patterns feature incomplete emptying, with post-void residuals up to 10-20% of capacity, interrupted streams, and detrusor-sphincter dyscoordination, as the central nervous system's inhibitory pathways remain underdeveloped until around 2-3 years. Voided volumes average 20-30 mL per episode, increasing with age, while pressures during voiding range from 50-100 cm H2O, sufficient for expulsion but prone to reflux risks in males due to anatomical factors like posterior urethral valves.[57] Absence of voiding by 48 hours warrants evaluation for dehydration or obstruction, as empirical data link delayed output to higher neonatal morbidity.[58]Childhood Acquisition of Control

In newborns and infants, urination occurs reflexively through a spinal arc involving the pontine micturition center, without voluntary cortical inhibition, leading to frequent voiding upon bladder filling.[59] This pattern persists until approximately 12-18 months, when initial sensory awareness of bladder fullness emerges, coinciding with myelination of descending inhibitory pathways from the cerebral cortex to the sacral spinal cord.[59] [60] Acquisition of voluntary control requires maturation of the external urethral sphincter and pelvic floor muscles, enabling the child to inhibit detrusor contraction and coordinate relaxation with abdominal pressure via the levator ani, thoracic diaphragm, and abdominal musculature.[60] Bladder capacity increases progressively, roughly doubling between ages 2 and 4.5 years, which supports longer intervals between voids and nighttime dryness.[60] By 2-3 years, most children gain basic sphincter control, allowing daytime continence with prompted training, though full adult-like voiding patterns, including complete cortical override of reflexes, typically solidify between 3 and 5 years.[61] [59] Girls generally achieve continence earlier than boys, with daytime control often by age 3 and nocturnal by 5, while boys may lag due to slower maturation of antidiuretic hormone secretion and deeper sleep patterns affecting arousal.[62] Readiness signs for toilet training include staying dry for 2 hours, predictable bowel movements, and interest in privacy, typically appearing around 18-24 months; forced early training before physiological readiness correlates with higher rates of persistent incontinence.[63] Delays beyond age 5 warrant evaluation for underlying issues like dysfunctional voiding, but 90-95% of healthy children achieve full control without intervention by school age.[59]Age-Related Changes in Adulthood

As individuals age into adulthood, the bladder's elastic tissue stiffens, reducing its stretchiness and maximum capacity, which typically holds less urine and impairs the ability to delay voiding after sensing fullness.[64] The detrusor muscle undergoes structural alterations, including increased collagen deposition, widened intercellular spaces between myocytes, and modifications in gap junctions, contributing to either overactivity—manifesting as involuntary contractions—or diminished contractility during voiding.[65] These changes often result in heightened urinary frequency, urgency, and nocturia, with overactive bladder affecting up to 40% of men and 30% of women aged 75 and older.[65] In men, benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) emerges as a primary age-related factor, with histologic prevalence reaching 50% by age 60 and 90% by age 85, leading to urethral obstruction and lower urinary tract symptoms such as hesitancy, weak stream, and incomplete emptying.[66] These symptoms impact approximately 38 million U.S. men over 30, progressing with age due to prostate enlargement compressing the urethra and altering detrusor dynamics.[67] In women, postmenopausal estrogen decline weakens pelvic floor muscles and urethral sphincter tone, elevating risks of stress and urge incontinence, with daily episodes reported in 9% to 39% of those over 60.[68] Both sexes experience sensory and neural shifts, including reduced bladder afferent sensitivity and disruptions in the brain-bladder axis, which diminish voluntary control over the voiding reflex and increase post-void residual urine volumes.[69] Urinary incontinence prevalence rises accordingly, affecting over 20% of seniors overall, with functional types predominant in institutional settings at rates up to 76%.[70][71] Kidney filtration declines concurrently, concentrating urine and exacerbating frequency, though these effects compound rather than solely cause micturition alterations.[72]Health and Clinical Considerations

Normal Parameters and Metrics

In healthy adults, urination frequency during waking hours typically ranges from 5 to 8 times per day, corresponding to intervals of approximately 3 to 4 hours, though reference ranges extend to 2 to 10 voids daily depending on fluid intake and individual variation.[73][74] Nocturnal voids (nocturia) are normally 0 to 1 time per night, with higher frequencies indicating potential pathology.[75] Daily urine output averages 800 to 2000 mL, or about 0.5 to 1 mL/kg body weight per hour, yielding roughly 1500 mL for a typical 70 kg adult under normal hydration (fluid intake of 2 L/day).[76][77] Volumes exceeding 2500 mL/day suggest polyuria, often linked to excessive intake or underlying conditions like diabetes mellitus.[78] Per-void volume in healthy individuals medians around 220 mL, with functional bladder capacity (maximum single void) spanning 400 to 600 mL before discomfort prompts urination.[79][80] Urinary flow rate, measured via uroflowmetry, averages 10 to 21 mL/second in men, declining with age (e.g., 21 mL/s in ages 14-45, 12 mL/s in 46-65, and 9 mL/s in 66-80), while women typically achieve 15 to 18 mL/s due to shorter urethral length and lower voiding pressures.[81][82] These metrics assume voided volumes of 150-300 mL; rates below 10 mL/s may signal obstruction, though no strict female norms exist owing to variability.[83] Urine composition reflects renal filtration efficiency, with normal pH ranging from 4.5 to 8.0 (typically 5.5 to 7.0, averaging 6.2), influenced by diet—acidic from high-protein intake, alkaline from vegetarian diets or infections.[84][85] Specific gravity, indicating concentration, falls between 1.005 and 1.030 in euvolemic states, below 1.005 signaling dilution (e.g., overhydration) and above 1.030 concentration (e.g., dehydration).[86] Urine is approximately 95% water, with solutes including urea (9-23 g/day), creatinine (1-2 g/day), electrolytes (sodium 20-40 mEq/L, potassium 25-125 mEq/L), and trace proteins (<150 mg/day), deviations from which aid diagnosis of renal or metabolic disorders.[85]| Parameter | Normal Range (Adults) | Notes/Sex/Age Variations |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency (day) | 5-8 voids | Up to 10 acceptable; influenced by intake[73] |

| Frequency (night) | 0-1 voids | >1 suggests nocturia[75] |

| Daily Output | 800-2000 mL | 0.5-1 mL/kg/h; avg. 1500 mL[77] |

| Void Volume | 150-500 mL (median 220 mL) | Max capacity 400-600 mL[79] |

| Flow Rate | 10-21 mL/s | Men: declines with age; women: 15-18 mL/s[81] |

| pH | 4.5-8.0 (avg. 6.2) | Diet-dependent[85] |

| Specific Gravity | 1.005-1.030 | Reflects hydration status[86] |

Pathological Conditions