Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Endianness

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2020) |

In computing, endianness is the order in which bytes within a word data type are transmitted over a data communication medium or addressed in computer memory, counting only byte significance compared to earliness. Endianness is primarily expressed as big-endian (BE) or little-endian (LE).

Computers store information in various-sized groups of binary bits. Each group is assigned a number, called its address, that the computer uses to access that data. On most modern computers, the smallest data group with an address is eight bits long and is called a byte. Larger groups comprise two or more bytes, for example, a 32-bit word contains four bytes.

There are two principal ways a computer could number the individual bytes in a larger group, starting at either end. A big-endian system stores the most significant byte of a word at the smallest memory address and the least significant byte at the largest. A little-endian system, in contrast, stores the least-significant byte at the smallest address.[1][2][3] Of the two, big-endian is thus closer to the way the digits of numbers are written left-to-right in English, comparing digits to bytes.

Both types of endianness are in widespread use in digital electronic engineering. The initial choice of endianness of a new design is often arbitrary, but later technology revisions and updates perpetuate the existing endianness to maintain backward compatibility. Big-endianness is the dominant ordering in networking protocols, such as in the Internet protocol suite, where it is referred to as network order, transmitting the most significant byte first. Conversely, little-endianness is the dominant ordering for processor architectures (x86, most ARM implementations, base RISC-V implementations) and their associated memory. File formats can use either ordering; some formats use a mixture of both or contain an indicator of which ordering is used throughout the file.[4]

Bi-endianness is a feature supported by numerous computer architectures that feature switchable endianness in data fetches and stores or for instruction fetches. Other orderings are generically called middle-endian or mixed-endian.[5][6][7][8]

Origin

[edit]

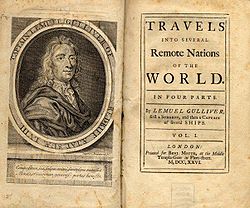

Endianness is primarily expressed as big-endian (BE) or little-endian (LE), terms introduced by Danny Cohen into computer science for data ordering in an Internet Experiment Note published in 1980.[9] The adjective endian has its origin in the writings of Anglo-Irish writer Jonathan Swift. In the 1726 novel Gulliver's Travels, he portrays the conflict between sects of Lilliputians divided into those breaking the shell of a boiled egg from the big end or from the little end.[10][11] By analogy, a CPU may read a digital word's big or little end first.

Characteristics

[edit]Computer memory consists of a sequence of storage cells (smallest addressable units); in machines that support byte addressing, those units are called bytes. Each byte is identified and accessed in hardware and software by its memory address. If the total number of bytes in memory is n, then addresses are enumerated from 0 to n − 1.

Computer programs often use data structures or fields that may consist of more data than can be stored in one byte. In the context of this article where its type cannot be arbitrarily complicated, a field consists of a consecutive sequence of bytes and represents a simple data value which – at least potentially – can be manipulated by one single hardware instruction. On most systems, the address of a multi-byte simple data value is the address of its first byte (the byte with the lowest address). There are exceptions to this rule – for example, the Add instruction of the IBM 1401 addresses variable-length fields at their low-order (highest-addressed) position with their lengths being defined by a word mark set at their high-order (lowest-addressed) position. When an operation such as addition is performed, the processor begins at the low-order positions at the high addresses of the two fields and works its way down to the high-order.[12]

Another important attribute of a byte being part of a field is its significance. These attributes of the parts of a field play an important role in the sequence the bytes are accessed by the computer hardware, more precisely: by the low-level algorithms contributing to the results of a computer instruction.

Numbers

[edit]Positional number systems (mostly base 2, or less often base 10) are the predominant way of representing and particularly of manipulating integer data by computers. In pure form this is valid for moderate sized non-negative integers, e.g. of C data type unsigned. In such a number system, the value of a digit that contributes to the whole number is determined not only by its value as a single digit, but also by the position it holds in the complete number, called its significance. These positions can be mapped to memory mainly in two ways:[13]

- Decreasing numeric significance with increasing memory addresses, known as big-endian and

- Increasing numeric significance with increasing memory addresses, known as little-endian.

In big-endian and little-endian, the end is the extremity where the big or little significance is written in the location indexed by the lowest memory address.

Text

[edit]When character (text) strings are to be compared with one another, e.g. in order to support some mechanism like sorting, this is very frequently done lexicographically where a single positional element (character) also has a positional value. Lexicographical comparison means almost everywhere: first character ranks highest – as in the telephone book. Almost all machines which can do this using a single instruction are big-endian or at least mixed-endian.[citation needed]

Integer numbers written as text are always represented most significant digit first in memory, which is similar to big-endian, independently of text direction.

Byte addressing

[edit]When memory bytes are printed sequentially from left to right (e.g. in a hex dump), little-endian representation of integers has the significance increasing from right to left. In other words, it appears backwards when visualized, which can be counter-intuitive.

This behavior arises, for example, in FourCC or similar techniques that involve packing characters into an integer, so that it becomes a sequence of specific characters in memory. For example, take the string "JOHN", stored in hexadecimal ASCII. On big-endian machines, the value appears left-to-right, coinciding with the correct string order for reading the result ("J O H N"). But on a little-endian machine, one would see "N H O J". Middle-endian machines complicate this even further; for example, on the PDP-11, the 32-bit value is stored as two 16-bit words "JO" "HN" in big-endian, with the characters in the 16-bit words being stored in little-endian, resulting in "O J N H".[14]

Byte swapping

[edit]Byte-swapping consists of rearranging bytes to change endianness. Many compilers provide built-ins that are likely to be compiled into native processor instructions (bswap/movbe), such as __builtin_bswap32. Software interfaces for swapping include:

- Standard network endianness functions (from/to BE, up to 32-bit).[15] Windows has a 64-bit extension in

winsock2.h. - BSD and Glibc

endian.hfunctions (from/to BE and LE, up to 64-bit).[16] - macOS

OSByteOrder.hmacros (from/to BE and LE, up to 64-bit). - The

std::byteswapfunction in C++23.[17]

Some CPU instruction sets provide native support for endian byte swapping, such as bswap[18] (x86 — 486 and later, i960 — i960Jx and later[19]), and rev[20] (ARMv6 and later).

Some compilers have built-in facilities for byte swapping. For example, the Intel Fortran compiler supports the non-standard CONVERT specifier when opening a file, e.g.: OPEN(unit, CONVERT='BIG_ENDIAN',...). Other compilers have options for generating code that globally enables the conversion for all file IO operations. This permits the reuse of code on a system with the opposite endianness without code modification.

Considerations

[edit]Simplified access to part of a field

[edit]On most systems, the address of a multi-byte value is the address of its first byte (the byte with the lowest address); little-endian systems of that type have the property that, for sufficiently low data values, the same value can be read from memory at different lengths without using different addresses (even when alignment restrictions are imposed). For example, a 32-bit memory location with content 4A 00 00 00 can be read at the same address as either 8-bit (value = 4A), 16-bit (004A), 24-bit (00004A), or 32-bit (0000004A), all of which retain the same numeric value. Although this little-endian property is rarely used directly by high-level programmers, it is occasionally employed by code optimizers as well as by assembly language programmers. While not allowed by C++, such type punning code is allowed as "implementation-defined" by the C11 standard[21] and commonly used[22] in code interacting with hardware.[23]

Calculation order

[edit]Some operations in positional number systems have a natural or preferred order in which the elementary steps are to be executed. This order may affect their performance on small-scale byte-addressable processors and microcontrollers. However, high-performance processors usually fetch multi-byte operands from memory in the same amount of time they would have fetched a single byte, so the complexity of the hardware is not affected by the byte ordering.

Addition, subtraction, and multiplication start at the least significant digit position and propagate the carry to the subsequent more significant position. On most systems, the address of a multi-byte value is the address of its first byte (the byte with the lowest address). The implementation of these operations is marginally simpler using little-endian machines where this first byte contains the least significant digit.

Comparison and division start at the most significant digit and propagate a possible carry to the subsequent less significant digits. For fixed-length numerical values (typically of length 1,2,4,8,16), the implementation of these operations is marginally simpler on big-endian machines.

Some big-endian processors (e.g. the IBM System/360 and its successors) contain hardware instructions for lexicographically comparing varying length character strings.

The normal data transport by an assignment statement is in principle independent of the endianness of the processor.

Hardware

[edit]Many historical and extant processors use a big-endian memory representation, either exclusively or as a design option. The IBM System/360 uses big-endian byte order, as do its successors System/370, ESA/390, and z/Architecture. The PDP-10 uses big-endian addressing for byte-oriented instructions. The IBM Series/1 minicomputer uses big-endian byte order. The Motorola 6800 / 6801, the 6809 and the 68000 series of processors use the big-endian format. Solely big-endian architectures include the IBM z/Architecture and OpenRISC. The PDP-11 minicomputer, however, uses little-endian byte order, as does its VAX successor.

The Datapoint 2200 used simple bit-serial logic with little-endian to facilitate carry propagation. When Intel developed the 8008 microprocessor for Datapoint, they used little-endian for compatibility. However, as Intel was unable to deliver the 8008 in time, Datapoint used a medium-scale integration equivalent, but the little-endianness was retained in most Intel designs, including the MCS-48 and the 8086 and its x86 successors, including IA-32 and x86-64 processors.[24][25] The MOS Technology 6502 family (including Western Design Center 65802 and 65C816), the Zilog Z80 (including Z180 and eZ80), the Altera Nios II, the Atmel AVR, the Andes Technology NDS32, the Qualcomm Hexagon, and many other processors and processor families are also little-endian.

The Intel 8051, unlike other Intel processors, expects 16-bit addresses for LJMP and LCALL in big-endian format; however, xCALL instructions store the return address onto the stack in little-endian format.[26]

Bi-endianness

[edit]Some instruction set architectures feature a setting which allows for switchable endianness in data fetches and stores, instruction fetches, or both; those instruction set architectures are referred to as bi-endian. Architectures that support switchable endianness include PowerPC/Power ISA, SPARC V9, ARM versions 3 and above, DEC Alpha, MIPS, Intel i860, PA-RISC, SuperH SH-4, IA-64, C-Sky, and RISC-V. This feature can improve performance or simplify the logic of networking devices and software. The word bi-endian, when said of hardware, denotes the capability of the machine to compute or pass data in either endian format.

Many of these architectures can be switched via software to default to a specific endian format (usually done when the computer starts up); however, on some systems, the default endianness is selected by hardware on the motherboard and cannot be changed via software (e.g. Alpha, which runs only in big-endian mode on the Cray T3E).

IBM AIX and IBM i run in big-endian mode on bi-endian Power ISA; Linux originally ran in big-endian mode, but by 2019, IBM had transitioned to little-endian mode for Linux to ease the porting of Linux software from x86 to Power.[27][28] SPARC has no relevant little-endian deployment, as both Oracle Solaris and Linux run in big-endian mode on bi-endian SPARC systems, and can be considered big-endian in practice. ARM, C-Sky, and RISC-V have no relevant big-endian deployments, and can be considered little-endian in practice.

The term bi-endian refers primarily to how a processor treats data accesses. Instruction accesses (fetches of instruction words) on a given processor may still assume a fixed endianness, even if data accesses are fully bi-endian, though this is not always the case, such as on Intel's IA-64-based Itanium CPU, which allows both.

Some nominally bi-endian CPUs require motherboard help to fully switch endianness. For instance, the 32-bit desktop-oriented PowerPC processors in little-endian mode act as little-endian from the point of view of the executing programs, but they require the motherboard to perform a 64-bit swap across all 8 byte lanes to ensure that the little-endian view of things will apply to I/O devices. In the absence of this unusual motherboard hardware, device driver software must write to different addresses to undo the incomplete transformation and also must perform a normal byte swap.[original research?]

Some CPUs, such as many PowerPC processors intended for embedded use and almost all SPARC processors, allow per-page choice of endianness.

SPARC processors since the late 1990s (SPARC v9 compliant processors) allow data endianness to be chosen with each individual instruction that loads from or stores to memory.

The ARM architecture supports two big-endian modes, called BE-8 and BE-32.[29] CPUs up to ARMv5 only support BE-32 or word-invariant mode. Here any naturally aligned 32-bit access works like in little-endian mode, but access to a byte or 16-bit word is redirected to the corresponding address and unaligned access is not allowed. ARMv6 introduces BE-8 or byte-invariant mode, where access to a single byte works as in little-endian mode, but accessing a 16-bit, 32-bit or (starting with ARMv8) 64-bit word results in a byte swap of the data. This simplifies unaligned memory access as well as memory-mapped access to registers other than 32-bit.

Many processors have instructions to convert a word in a register to the opposite endianness, that is, they swap the order of the bytes in a 16-, 32- or 64-bit word.

Recent Intel x86 and x86-64 architecture CPUs have a MOVBE instruction (Intel Core since generation 4, after Atom),[30] which fetches a big-endian format word from memory or writes a word into memory in big-endian format. These processors are otherwise thoroughly little-endian.

There are also devices which use different formats in different places. For instance, the BQ27421 Texas Instruments battery gauge uses the little-endian format for its registers and the big-endian format for its random-access memory.

SPARC historically used big-endian until version 9, which is bi-endian. Similarly early IBM POWER processors were big-endian, but the PowerPC and Power ISA descendants are now bi-endian. The ARM architecture was little-endian before version 3 when it became bi-endian.

Floating point

[edit]Although many processors use little-endian storage for all types of data (integer, floating point), there are a number of hardware architectures where floating-point numbers are represented in big-endian form while integers are represented in little-endian form.[31] There are ARM processors that have mixed-endian floating-point representation for double-precision numbers: each of the two 32-bit words is stored as little-endian, but the most significant word is stored first. VAX floating point stores little-endian 16-bit words in big-endian order. Because there have been many floating-point formats with no network standard representation for them, the XDR standard uses big-endian IEEE 754 as its representation. It may therefore appear strange that the widespread IEEE 754 floating-point standard does not specify endianness.[32] Theoretically, this means that even standard IEEE floating-point data written by one machine might not be readable by another. However, on modern standard computers (i.e., implementing IEEE 754), one may safely assume that the endianness is the same for floating-point numbers as for integers, making the conversion straightforward regardless of data type. Small embedded systems using special floating-point formats may be another matter, however.

Variable-length data

[edit]Most instructions considered so far contain the size (lengths) of their operands within the operation code. Frequently available operand lengths are 1, 2, 4, 8, or 16 bytes. But there are also architectures where the length of an operand may be held in a separate field of the instruction or with the operand itself, e.g. by means of a word mark. Such an approach allows operand lengths up to 256 bytes or larger. The data types of such operands are character strings or BCD. Machines able to manipulate such data with one instruction (e.g. compare, add) include the IBM 1401, 1410, 1620, System/360, System/370, ESA/390, and z/Architecture, all of them of type big-endian.

Middle-endian

[edit]Numerous other orderings, generically called middle-endian or mixed-endian, are possible.

The PDP-11 is primarily a 16-bit little-endian system. The instructions to convert between floating-point and integer values in the optional floating-point processor of the PDP-11/45, PDP-11/70, and in some later processors, stored 32-bit double precision integer long values with the 16-bit halves swapped from the expected little-endian order. The UNIX C compiler used the same format for 32-bit long integers. This ordering is known as PDP-endian.[33]

UNIX was one of the first systems to allow the same code to be compiled for platforms with different internal representations. One of the first programs converted was supposed to print out Unix, but on the Series/1 it printed nUxi instead.[34]

A way to interpret this endianness is that it stores a 32-bit integer as two little-endian 16-bit words, with a big-endian word ordering:

| byte offset | 8-bit value | 16-bit little-endian value |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0Bh | 0A0Bh |

| 1 | 0Ah | |

| 2 | 0Dh | 0C0Dh |

| 3 | 0Ch |

Segment descriptors of IA-32 and compatible processors keep a 32-bit base address of the segment stored in little-endian order, but in four nonconsecutive bytes, at relative positions 2, 3, 4 and 7 of the descriptor start.[35]

Software

[edit]Logic design

[edit]Hardware description languages (HDLs) used to express digital logic often support arbitrary endianness, with arbitrary granularity. For example, in SystemVerilog, a word can be defined as little-endian or big-endian.[citation needed]

Files and filesystems

[edit]The recognition of endianness is important when reading a file or filesystem created on a computer with different endianness.

Fortran sequential unformatted files created with one endianness usually cannot be read on a system using the other endianness because Fortran usually implements a record (defined as the data written by a single Fortran statement) as data preceded and succeeded by count fields, which are integers equal to the number of bytes in the data. An attempt to read such a file using Fortran on a system of the other endianness results in a run-time error, because the count fields are incorrect.

Unicode text can optionally start with a byte order mark (BOM) to signal the endianness of the file or stream. Its code point is U+FEFF. In UTF-32 for example, a big-endian file should start with 00 00 FE FF; a little-endian should start with FF FE 00 00.

Application binary data formats, such as MATLAB .mat files, or the .bil data format, used in topography, are usually endianness-independent. This is achieved by storing the data always in one fixed endianness or carrying with the data a switch to indicate the endianness. An example of the former is the binary XLS file format that is portable between Windows and Mac systems and always little-endian, requiring the Mac application to swap the bytes on load and save when running on a big-endian Motorola 68K or PowerPC processor.[36]

TIFF image files are an example of the second strategy, whose header instructs the application about the endianness of their internal binary integers. If a file starts with the signature MM it means that integers are represented as big-endian, while II means little-endian. Those signatures need a single 16-bit word each, and they are palindromes, so they are endianness independent. I stands for Intel and M stands for Motorola. Intel CPUs are little-endian, while Motorola 680x0 CPUs are big-endian. This explicit signature allows a TIFF reader program to swap bytes if necessary when a given file was generated by a TIFF writer program running on a computer with a different endianness.

As a consequence of its original implementation on the Intel 8080 platform, the operating system-independent File Allocation Table (FAT) file system is defined with little-endian byte ordering, even on platforms using another endianness natively, necessitating byte-swap operations for maintaining the FAT on these platforms.

ZFS, which combines a filesystem and a logical volume manager, is known to provide adaptive endianness and to work with both big-endian and little-endian systems.[37]

Networking

[edit]Many IETF RFCs use the term network order, meaning the order of transmission for bytes over the wire in network protocols. Among others, the historic RFC 1700 defines the network order for protocols in the Internet protocol suite to be big-endian.[38]

However, not all protocols use big-endian byte order as the network order. The Server Message Block (SMB) protocol uses little-endian byte order. In CANopen, multi-byte parameters are always sent least significant byte first (little-endian). The same is true for Ethernet Powerlink.[39]

The Berkeley sockets API defines a set of functions to convert 16- and 32-bit integers to and from network byte order: the htons (host-to-network-short) and htonl (host-to-network-long) functions convert 16- and 32-bit values respectively from machine (host) to network order; the ntohs and ntohl functions convert from network to host order.[40][41] These functions may be a no-op on a big-endian system.

While the high-level network protocols usually consider the byte (mostly meant as octet) as their atomic unit, the lowest layers of a network stack may deal with ordering of bits within a byte. Bit ordering is sometimes referred to as little-endian or big-endian, but this not standard. Bit ordering does not need to be the same as byte ordering. For example, RS-232 transmits bits least significant first, I2C transmits bits most significant first, and SPI can be sent in either order. Ethernet transmits individual bits least significant first, but bytes are sent big-endian.

See also

[edit]- Bit order – Convention to identify bit positions

References

[edit]- ^ "Understanding big and little endian byte order". betterexplained.com. Archived from the original on 2019-05-24. Retrieved 2019-05-20.

- ^ "Byte Ordering PPC". Archived from the original on 2019-05-09. Retrieved 2019-05-20.

- ^ "Writing endian-independent code in C". Archived from the original on 2019-06-10. Retrieved 2019-05-20.

- ^ A File Format for the Exchange of Images in the Internet. April 1992. p. 7. doi:10.17487/RFC1314. RFC 1314. Retrieved 2021-08-16.

- ^ "Internet Hall of Fame Pioneer". Internet Hall of Fame. The Internet Society. Archived from the original on 2021-07-21. Retrieved 2015-10-07.

- ^ Cary, David. "Endian FAQ". Archived from the original on 2017-11-09. Retrieved 2010-10-11.

- ^ James, David V. (June 1990). "Multiplexed buses: the endian wars continue". IEEE Micro. 10 (3): 9–21. doi:10.1109/40.56322. ISSN 0272-1732. S2CID 24291134.

- ^ Blanc, Bertrand; Maaraoui, Bob (December 2005). "Endianness or Where is Byte 0?" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2007-12-03. Retrieved 2008-12-21.

- ^ Cohen, Danny (1980-04-01). On Holy Wars and a Plea for Peace. IETF. IEN 137. Also published at Cohen, Danny (October 1981). "On Holy Wars and a Plea for Peace". IEEE Computer. 14 (10): 48–54. doi:10.1109/C-M.1981.220208.

- ^ Swift, Jonathan (1726). "A Voyage to Lilliput, Chapter IV". Gulliver's Travels. Archived from the original on 2022-09-20. Retrieved 2022-09-20.

- ^ Bryant, Randal E.; David, O'Hallaron (2016), Computer Systems: A Programmer's Perspective (3 ed.), Pearson Education, p. 79, ISBN 978-1-488-67207-1

- ^ IBM 1401 System Summary (PDF). IBM. April 1966. p. 15. A24-1401-1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-10.

- ^ Tanenbaum, Andrew S.; Austin, Todd M. (4 August 2012). Structured Computer Organization. Prentice Hall PTR. ISBN 978-0-13-291652-3. Retrieved 18 May 2013.

- ^ PDP11 processor handbook – PDP11/05/10/35/40 (PDF). Digital Equipment Corporation. April 1973. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2025-07-02. See Figure 2-6

- ^ – Linux Programmer's Manual – Library Functions from Manned.org

- ^ – Linux Programmer's Manual – Library Functions from Manned.org

- ^ "std::byteswap". en.cppreference.com. Archived from the original on 20 November 2023. Retrieved 3 October 2023.

- ^ "Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer's Manual Volume 2 (2A, 2B & 2C): Instruction Set Reference, A-Z" (PDF). Intel. September 2016. p. 3–112. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved 2017-02-05.

- ^ "i960® VH Processor Developer's Manual" (PDF). Intel. October 1998. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2024-04-02. Retrieved 2024-04-02.

- ^ "ARMv8-A Reference Manual". ARM Holdings. Archived from the original on 2019-01-19. Retrieved 2017-02-05.

- ^ "C11 standard". ISO. Section 6.5.2.3 "Structure and Union members", §3 and footnote 95. Archived from the original on 28 March 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^ "3.10 Options That Control Optimization: -fstrict-aliasing". GNU Compiler Collection (GCC). Free Software Foundation. Archived from the original on 1 July 2023. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^ Torvalds, Linus (5 Jun 2018). "[GIT PULL] Device properties framework update for v4.18-rc1". Linux Kernel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 15 August 2018. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^ House, David; Faggin, Federico; Feeney, Hal; Gelbach, Ed; Hoff, Ted; Mazor, Stan; Smith, Hank (2006-09-21). "Oral History Panel on the Development and Promotion of the Intel 8008 Microprocessor" (PDF). Computer History Museum. p. b5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-06-29. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ^ Lunde, Ken (13 January 2009). CJKV Information Processing. O'Reilly Media, Inc. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-596-51447-1. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ^ "Cx51 User's Guide: E. Byte Ordering". keil.com. Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2015-03-28.

- ^ Jeff Scheel (2016-06-16). "Little endian and Linux on IBM Power Systems". IBM. Archived from the original on 2022-03-27. Retrieved 2022-03-27.

- ^ Timothy Prickett Morgan (10 June 2019). "The Transition To RHEL 8 Begins On Power Systems". ITJungle. Archived from the original on 24 January 2022. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- ^ "Differences between BE-32 and BE-8 buses". Archived from the original on 2019-02-12. Retrieved 2019-02-10.

- ^ "How to detect New Instruction support in the 4th generation Intel® Core™ processor family" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 March 2016. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- ^ Savard, John J. G. (2018) [2005], "Floating-Point Formats", quadibloc, archived from the original on 2018-07-03, retrieved 2018-07-16

- ^ "pack – convert a list into a binary representation". Archived from the original on 2009-02-18. Retrieved 2009-02-04.

- ^ PDP-11/45 Processor Handbook (PDF). Digital Equipment Corporation. 1973. p. 165. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^ Jalics, Paul J.; Heines, Thomas S. (1 December 1983). "Transporting a portable operating system: UNIX to an IBM minicomputer". Communications of the ACM. 26 (12): 1066–1072. doi:10.1145/358476.358504. S2CID 15558835.

- ^ AMD64 Architecture Programmer's Manual Volume 2: System Programming (PDF) (Technical report). 2013. p. 80. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-02-18.

- ^ "Microsoft Office Excel 97 - 2007 Binary File Format Specification (*.xls 97-2007 format)". Microsoft Corporation. 2007. Archived from the original on 2008-12-22. Retrieved 2014-08-18.

- ^ Matt Ahrens (2016). FreeBSD Kernel Internals: An Intensive Code Walkthrough. OpenZFS Documentation/Read Write Lecture. Archived from the original on 2016-04-14. Retrieved 2016-03-30.

- ^ Reynolds, J.; Postel, J. (October 1994). "Data Notations". Assigned Numbers. IETF. p. 3. doi:10.17487/RFC1700. STD 2. RFC 1700. Retrieved 2012-03-02.

- ^ Ethernet POWERLINK Standardisation Group (2012), EPSG Working Draft Proposal 301: Ethernet POWERLINK Communication Profile Specification Version 1.1.4, chapter 6.1.1.

- ^ IEEE and The Open Group (2018). "3. System Interfaces". The Open Group Base Specifications Issue 7. Vol. 2. p. 1120. Archived from the original on 2021-04-18. Retrieved 2021-04-09.

- ^ "htonl(3) - Linux man page". linux.die.net. Archived from the original on 2021-04-18. Retrieved 2021-04-09.

External links

[edit] The dictionary definition of endianness at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of endianness at Wiktionary

Endianness

View on Grokipediahtonl and ntohl functions, to translate between host and network orders. Bi-endian support in architectures like ARM and PowerPC allows flexibility for legacy compatibility or specialized applications, though little-endian dominates in consumer computing due to the influence of x86 and ARM ecosystems. Understanding endianness remains essential for developers working on low-level programming, embedded systems, and data serialization to prevent subtle bugs in multi-platform environments.

Fundamentals

Definition and Types

Endianness is the attribute of a data representation scheme that specifies the ordering of bytes within a multi-byte numeric value when stored in memory or transmitted over a network.[8] The term "endian" draws from Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels, alluding to the fictional conflict between those who break eggs at the big end and those at the little end.[4] The two primary types of endianness are big-endian and little-endian. In big-endian ordering, also known as network byte order, the most significant byte (containing the highest-order bits) is stored first, followed by bytes of decreasing significance.[8] This mirrors the conventional left-to-right reading of multi-digit decimal numbers, where the leftmost digit represents the highest place value (e.g., in 1234, '1' is the thousands place).[8] For instance, the 32-bit hexadecimal value0x12345678 is represented in big-endian format as the byte sequence 12 34 56 78 in consecutive memory addresses.[8]

In little-endian ordering, the least significant byte is stored first, followed by bytes of increasing significance.[8] Using the same example, the value 0x12345678 appears as 78 56 34 12 in memory.[8] This arrangement prioritizes the lower-order bytes at lower memory addresses, which can simplify certain arithmetic operations but requires awareness when interpreting data across systems.[9]

Historical Origin

The terms "big-endian" and "little-endian" originated as a metaphor in computing from Jonathan Swift's 1726 satirical novel Gulliver's Travels, where the Big-Endians and Little-Endians represent two nations engaged in a protracted war over the proper end from which to crack a boiled egg—the larger end for the former and the smaller end for the latter.[10] This allegory of absurd division was adopted by computer scientist Danny Cohen in his 1980 paper "On Holy Wars and a Plea for Peace" (Internet Experiment Note 137) to describe the escalating debates over byte ordering in multi-byte data representations.[4][11] In the paper, Cohen equated big-endian systems—those storing the most significant byte first—with Swift's Big-Endians, and little-endian systems—storing the least significant byte first—with the Little-Endians, urging the community to resolve the "holy war" through standardization rather than continued conflict.[4] In the early days of computing during the 1970s, these byte order conventions emerged prominently in divergent hardware architectures, exacerbating data exchange challenges. Digital Equipment Corporation's PDP-11 minicomputers, widely used for systems like early UNIX, employed little-endian ordering for 16-bit words, placing the least significant byte at the lowest memory address.[12][13] In contrast, IBM's System/360 and subsequent mainframe series adopted big-endian ordering, aligning with conventions from punch-card tabulating machines where numeric fields were read from left to right in human-readable form.[7][14] This mismatch led to notorious interoperability issues, such as the "NUXI" problem, where the four-byte representation of the string "UNIX" (U=0x55, N=0x4E, I=0x49, X=0x58) appeared as "NUXI" when transferred between a PDP-11 (mixed-endian for 32-bit values) and a big-endian IBM system, garbling file names and data structures during network transfers.[15][16] The byte order disputes intensified during the ARPANET protocol development in the late 1970s, as researchers connected heterogeneous machines—including little-endian PDP-11s and big-endian systems like the PDP-10—leading to fervent discussions on mailing lists and working groups about how to ensure reliable data transmission.[17][18] Cohen's 1980 paper directly addressed this "holy war," framing the ARPANET's ongoing conflicts as analogous to Swift's egg-cracking schism and advocating for a neutral, consistent order in protocols to avoid architecture-specific assumptions.[4] These debates highlighted the need for a universal convention, influencing the broader networking community to prioritize interoperability over platform preferences. Cohen's work played a pivotal role in shaping subsequent standards, particularly in adopting big-endian as the "network byte order" for internet protocols. This convention was formalized in RFC 791 (1981), which defines the Internet Protocol and specifies big-endian ordering for all multi-byte integer fields to guarantee consistent interpretation across diverse hosts, regardless of their native endianness.[19] Similarly, the IEEE 754 standard for binary floating-point arithmetic, ratified in 1985, defines the logical bit layout for numbers but leaves byte serialization flexible, permitting both big- and little-endian implementations. In practice, big-endian is often used for interchange to align with network conventions.[20] These developments marked a shift toward protocol-level standardization, mitigating the historical tensions Cohen had illuminated.Data Representation

Integers and Numeric Types

In multi-byte integer storage, endianness determines the sequence of bytes in memory relative to the starting address. Big-endian systems place the most significant byte (MSB) at the lowest address, followed by progressively less significant bytes, mimicking the left-to-right order of written numbers. Little-endian systems reverse this, storing the least significant byte (LSB) first. This arrangement applies to integers of various sizes, such as 16-bit, 32-bit, and 64-bit types.[21][22] For example, the unsigned 16-bit integer 258 (0x0102) is stored in big-endian as bytes01 02 and in little-endian as 02 01. A 32-bit unsigned integer like 0x12345678 appears as 12 34 56 78 in big-endian memory and 78 56 34 12 in little-endian. Extending to 64-bit, the pattern continues with eight bytes ordered by significance, such as 0x1122334455667788 as 11 22 33 44 55 66 77 88 (big-endian) or 88 77 66 55 44 33 22 11 (little-endian). These examples illustrate how the same bit pattern yields different byte layouts, affecting direct memory inspection or serialization.[23][24][22]

Signed integers, typically represented in two's complement, follow the identical byte-ordering rules as unsigned ones, with the sign bit embedded in the MSB. For the 32-bit signed integer -1 (0xFFFFFFFF), all bytes are FF, resulting in FF FF FF FF in both big- and little-endian storage, preserving the value across formats. In contrast, -2 (0xFFFFFFFE) is stored as FF FF FF FE in big-endian and FE FF FF FF in little-endian, highlighting byte reversal effects.[22][23]

Endianness treats signed and unsigned integers uniformly in storage, as the distinction lies in interpretation rather than arrangement. However, cross-endian misinterpretation poses risks, such as altering the perceived sign. For instance, the little-endian bytes for -2 (FE FF FF FF) read as big-endian yield 0xFEFFFFFF, a large negative value (-16777216 in signed 32-bit), but swapping orders for values like 0xFF000000 (negative in big-endian) can produce 0x000000FF (positive 255 in little-endian misread as big-endian), effectively flipping the sign and leading to erroneous computations.[22][23]

To reconstruct an integer value from its bytes, big-endian uses the formula where the MSB contributes the highest weight:

For a 32-bit integer (), this equates to bit-shift operations: \text{value} = (\text{byte}{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=0&&&citation_type=wikipedia}} \ll 24) \lor (\text{byte}{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=1&&&citation_type=wikipedia}} \ll 16) \lor (\text{byte}{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=2&&&citation_type=wikipedia}} \ll 8) \lor \text{byte}{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}, with denoting left shift and bitwise OR. In little-endian, bytes must be reversed before applying the same reconstruction, or shifts adjusted to prioritize the LSB (e.g., \text{byte}{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=3&&&citation_type=wikipedia}} \ll 24 \lor \cdots \lor \text{byte}{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=0&&&citation_type=wikipedia}}). Generalizing for bytes, the big-endian shifts are \text{byte}{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=0&&&citation_type=wikipedia}} \ll (n-1)\times 8 \lor \text{byte}{{grok:render&&&type=render_inline_citation&&&citation_id=1&&&citation_type=wikipedia}} \ll (n-2)\times 8 \lor \cdots \lor \text{byte}[n-1]. Failure to match the source endianness during reconstruction inverts the value.[21][22]

A frequent pitfall arises when accessing partial bytes of a multi-byte integer across endian boundaries, such as reading only the lower bytes without reordering, which truncates or misaligns the value and can propagate errors like unintended sign extension or magnitude distortion in subsequent operations.[21][24] Similar byte-order considerations extend to floating-point representations, though their structured formats introduce additional complexity.[22]

Text and Character Encoding

Single-byte character encodings, such as ASCII and the ISO-8859 family, are unaffected by endianness because each character is represented by a single byte, eliminating any need for byte ordering across multiple bytes.[25] In contrast, multi-byte encodings like UTF-16 are sensitive to endianness, as characters are encoded using 16-bit code units that must be serialized into bytes. UTF-16 big-endian (UTF-16BE) stores the most significant byte first, while UTF-16 little-endian (UTF-16LE) stores the least significant byte first. To resolve ambiguity in byte order, the byte order mark (BOM), represented by the Unicode character U+FEFF (encoded as 0xFEFF), is commonly placed at the beginning of a UTF-16 data stream. The BOM appears as the byte sequence FE FF in big-endian order, indicating UTF-16BE, or FF FE in little-endian order, indicating UTF-16LE; upon reading the file, the initial two bytes are examined to determine and apply the appropriate endianness for decoding the rest of the content.[26][27] For example, the Unicode character "A" (U+0041) in UTF-16 is encoded as the 16-bit value 0041. In big-endian byte order, this becomes the sequence00 41; in little-endian, it is 41 00. If a BOM precedes this, a big-endian file might start with FE FF 00 41, while a little-endian one starts with FF FE 41 00.[26][25]

The legacy UCS-2 encoding, an early fixed-width 16-bit format from the initial Unicode versions in the early 1990s, exacerbated endianness issues because it typically lacked a standardized BOM, leading to frequent misinterpretation of text when files were exchanged between big-endian and little-endian systems without explicit order specification.[28][27]

UTF-8, however, is immune to endianness concerns, as it employs a variable-length encoding of 1 to 4 bytes per character where the byte sequence for each character is self-describing and does not rely on a fixed multi-byte order, making it compatible across different system architectures without additional markers.[25]

Memory Addressing and Byte Order

In byte-addressable memory models, each individual byte in the system's address space is assigned a unique address, allowing processors to access data at the granularity of single bytes. Multi-byte data types, such as 16-bit or 32-bit integers, are stored across a sequence of consecutive byte addresses, with the starting address typically referring to the first byte in that sequence. This model is fundamental to most modern computer architectures, enabling flexible data manipulation while requiring careful consideration of byte ordering for correct interpretation.[29] In big-endian addressing, the most significant byte (MSB) of a multi-byte value is stored at the lowest (starting) address, followed by subsequent bytes in order of decreasing significance across increasing addresses. For example, the 32-bit value 0x12345678 stored at base address 0x00400000 would occupy bytes as follows: 0x12 at 0x00400000 (MSB), 0x34 at 0x00400001, 0x56 at 0x00400002, and 0x78 at 0x00400003 (least significant byte, LSB). This convention aligns the byte order with the natural reading direction of numbers, resembling how humans interpret decimal values from left to right.[24] Conversely, in little-endian addressing, the least significant byte (LSB) is placed at the lowest address, with bytes arranged in order of increasing significance as addresses rise. Using the same 32-bit value 0x12345678 at base address 0x00400000, the storage would be: 0x78 at 0x00400000 (LSB), 0x56 at 0x00400001, 0x34 at 0x00400002, and 0x12 at 0x00400003 (MSB). This approach facilitates certain arithmetic operations by positioning lower-order bytes closer to the processor's addressing logic, though it reverses the intuitive byte sequence.[24] When processors perform word-aligned access, they fetch multi-byte words (e.g., 32-bit or 64-bit units) from memory addresses that are multiples of the word size, ensuring efficient bus utilization without partial reads. The endianness of the system determines how the fetched bytes are interpreted into the word value, with the hardware automatically mapping the byte sequence to the appropriate significance without requiring address adjustments by the programmer. For instance, in a little-endian system, a 32-bit fetch from an aligned address 0x1000 would combine bytes from 0x1000 (LSB) through 0x1003 (MSB) into the final value.[30] A key implication of endianness arises in debugging, particularly when examining hex dumps of memory contents. In little-endian systems, multi-byte values appear with their bytes reversed relative to the logical numerical order—LSB first from low to high addresses—necessitating mental reordering by developers to match the expected value, which can introduce errors in manual inspection or cross-platform analysis. This byte reversal in dumps is less pronounced in big-endian systems, where the sequence aligns more directly with standard hexadecimal notation.[29]Conversion and Manipulation

Byte Swapping Methods

Byte swapping methods provide essential techniques for converting multi-byte data between little-endian and big-endian formats, ensuring compatibility across diverse hardware architectures. In software implementations, these methods often rely on bitwise operations to rearrange bytes without altering the underlying data values. For a 16-bit integer, a simple byte swap can be achieved using right and left shifts combined with a bitwise OR:swapped = (x >> 8) | (x << 8);, which exchanges the least significant byte with the most significant byte.[31]

For 32-bit integers, the process extends to multiple byte pairs and requires additional masking to isolate and reposition each byte correctly. A common efficient algorithm uses two passes of swapping adjacent byte pairs: first, swap bits 0-7 with 8-15 and 16-23 with 24-31 using n = ((n << 8) & 0xFF00FF00) | ((n >> 8) & 0x00FF00FF);, then swap the resulting 16-bit halves with n = (n << 16) | (n >> 16);. This method minimizes operations while handling the full word. For 64-bit values, the technique builds on the 32-bit approach by applying similar pairwise swaps across eight bytes, often using compiler intrinsics like GCC's __builtin_bswap64 for optimization, or explicit shifts and masks extended to 64 bits: for instance, isolating and repositioning bytes in stages similar to the 32-bit case but covering the full range.[31]

In C programming, standard library functions facilitate byte swapping, particularly for network communications where big-endian is the conventional order. The htonl() function converts a 32-bit host integer to network byte order, while ntohl() performs the reverse conversion from network to host order; these assume network byte order is big-endian and are no-ops on big-endian hosts.[32] Similar functions htons() and ntohs() handle 16-bit values. These are defined in POSIX standards and included via <arpa/inet.h>, providing portable abstractions over low-level bitwise operations. For example:

#include <arpa/inet.h>

uint32_t network_int = htonl(host_int); // Host to network (big-endian)

uint32_t host_int = ntohl(network_int); // Network to host

#include <arpa/inet.h>

uint32_t network_int = htonl(host_int); // Host to network (big-endian)

uint32_t host_int = ntohl(network_int); // Network to host

__BYTE_ORDER__ macro equals __ORDER_LITTLE_ENDIAN__, __ORDER_BIG_ENDIAN__, or __ORDER_PDP_ENDIAN__ based on the target's byte layout, allowing conditional compilation or runtime checks like #if __BYTE_ORDER__ == __ORDER_LITTLE_ENDIAN__.[36] Alternatively, processor-specific checks or unions with known values can probe endianness dynamically.

Performance considerations favor hardware instructions or inline assembly over library calls in high-throughput scenarios, such as network packet processing. On x86-64, using BSWAP via inline assembly for 64-bit swaps can reduce execution time compared to pure C macros in microbenchmarks involving millions of operations, as it avoids branch predictions and function call overhead.[37] Library functions like htonl() introduce minimal overhead on modern compilers but may underperform in loops without inlining; thus, developers often prefer intrinsics or assembly for latency-sensitive code.

Handling Partial Data Access

In multi-byte data structures, accessing or modifying individual bytes or bit fields without performing a complete endianness conversion is essential for efficiency and precision, particularly in low-level programming where preserving the overall byte order is necessary. This approach avoids unnecessary overhead from full swaps while allowing targeted operations on serialized or in-memory data. Techniques such as unions, bit manipulation, and pointer arithmetic enable developers to manipulate partial components directly, accounting for the host system's endianness to ensure correct interpretation.[38] In the C programming language, unions facilitate direct byte-level access by overlaying a multi-byte type, such as an integer, with a byte array or structure, allowing manipulation of specific bytes while inherently reflecting the system's endianness. For instance, a union containing a 16-bit unsigned integer and two 8-bit unsigned integers enables packing bytes into the larger type or unpacking them without altering the byte order, as the shared memory layout preserves the native representation. This method is particularly useful for handling serialized data streams, where endianness must match the source format during partial reads or writes. However, care must be taken, as the union's behavior aligns with the processor's endianness—little-endian systems store the least significant byte first, while big-endian systems store the most significant byte first.[39] Bit-field extraction techniques, involving masking and shifting, provide a portable way to isolate and modify specific bytes within a multi-byte value, independent of full conversions. Extracting the high byte from a 32-bit integer can be achieved by right-shifting the value by 24 bits and applying a mask of 0xFF, as in(value >> 24) & 0xFF, which positions the most significant byte for access without disturbing the remaining bytes. This approach uses logical operations to create masks—such as shifting 1 left by the desired bit position and subtracting 1 for a contiguous field—and is preferred over bit fields in structures due to the latter's implementation-defined ordering, which can vary across compilers and introduce endianness inconsistencies. Bit fields themselves subdivide registers into smaller units, supporting masking to clear or set portions and shifting to align extracted bits, but their allocation direction (from least or most significant bit) often requires explicit handling to avoid portability issues.[40][41]

Pointer arithmetic with character pointers offers a reliable method for partial reads, as incrementing a char* or unsigned char* advances by exactly one byte, bypassing the host's multi-byte alignment and endianness for granular access. By casting a pointer to a multi-byte type (e.g., int*) to unsigned char*, developers can iterate over individual bytes—such as ptr[0] for the first byte—enabling inspection or modification without assuming field order. This technique is endian-independent for byte traversal but requires awareness of the system's order when interpreting the bytes' significance, such as verifying if the least significant byte resides at the lowest address in little-endian architectures.[38]

Cross-platform code faces significant challenges when handling partial data access in serialized formats, as differing endianness between source and target systems can lead to misordered fields, causing errors in data interpretation without explicit byte-level validation. For example, assuming a fixed field order in network packets or files—common in protocols like TCP/IP, which use big-endian—may result in incorrect partial extractions on little-endian hosts unless conversions are applied selectively to affected bytes. To mitigate this, code often standardizes on network byte order for serialization and uses runtime endianness detection to adjust only the necessary portions, ensuring portability across architectures like x86 (little-endian) and SPARC (big-endian).[42][38]

A practical example is modifying only the upper 16 bits of a 32-bit integer while leaving the lower 16 bits intact, which can be done using bit manipulation to mask and merge without a full swap. Start by masking out the upper bits with value &= 0x0000FFFF; to clear them, then shift the new 16-bit value left by 16 bits and OR it in: value |= (new_upper << 16);. This preserves the original lower bits and the overall endianness, as the operations treat the value as a bit stream rather than reversing byte order. Such selective updates are common in embedded systems or protocol handling, where only specific fields need alteration.[31]

System-Level Implications

Arithmetic Operations and Order

In little-endian systems, the storage of the least significant byte (LSB) at the lowest memory address facilitates carry propagation during addition, as arithmetic operations naturally begin with the LSB and proceed toward higher significance, mirroring the sequential processing in calculators and multi-precision computations.[43] This alignment reduces the need for byte reversal in software simulations of hardware arithmetic, particularly in bit-serial processors where carries must propagate from low to high order bits.[44] Conversely, big-endian systems store the most significant byte first, requiring potential reversal of byte order to simulate the same LSB-first processing flow in certain algorithmic implementations.[45] For multiplication and division on multi-byte integers, endianness becomes irrelevant once the data is loaded into processor registers, as the arithmetic units operate on the reconstructed scalar value regardless of storage order.[46] However, if input data remains in unswapped memory form—such as when bytes are accessed directly without proper loading—the resulting computations will yield incorrect products or quotients due to misinterpreted numerical values.[47] Consider an example of adding two 16-bit values, 0x1234 and 0xABCD, stored in little-endian memory. The first number occupies addresses 0x1000 (LSB: 0x34) and 0x1001 (MSB: 0x12); the second occupies 0x1002 (LSB: 0xCD) and 0x1003 (MSB: 0xAB). When loaded into registers via little-endian-aware instructions, the values are correctly interpreted as 0x1234 and 0xABCD, and their sum is 0xBE01, with the carry propagating naturally from the LSB without requiring byte manipulation. In a multi-precision context, such as big-integer libraries like GMP, limbs (fixed-width words) are stored in little-endian order to enable efficient carry propagation across limbs during addition, starting from the least significant limb.[48] Compilers typically generate endian-agnostic code for core arithmetic operations, relying on hardware load/store instructions to handle byte ordering transparently, ensuring the same assembly sequences for addition or multiplication across endianness variants.[49] However, they may expose endian-specific intrinsics, such as byte-swap functions (e.g., GCC's__builtin_bswap16), for low-level optimizations in performance-critical code involving direct memory access.

Endianness-related bugs in arithmetic often arise from misordered byte access, leading to erroneous results; for instance, interpreting the little-endian bytes of 0x1234 (0x34, 0x12) as big-endian yields 0x3412, so adding it to similarly misinterpreted 0xABCD (0xCD, 0xAB → 0xCDAB) produces 0x101BD instead of the correct 0xBE01.[47] Such issues are common in cross-platform software or when manipulating raw binary data without endian conversion, complicating debugging as the errors manifest as subtle numerical discrepancies rather than crashes.[50]

Bi-endian and Configurable Systems

Bi-endian processors support both big-endian and little-endian byte orders, allowing flexibility in data representation based on system requirements. This capability is implemented through dedicated control bits in processor registers, enabling runtime or boot-time configuration without hardware redesign. Such systems are particularly valuable in environments where compatibility with diverse peripherals or protocols is essential, as they mitigate the need for extensive software byte-swapping. In the ARM architecture, starting from version 3, endianness is configurable via the E bit (bit 9) in the Current Program Status Register (CPSR), where a value of 0 denotes little-endian operation and 1 indicates big-endian. Similarly, MIPS processors use the Reverse Endian (RE) bit (bit 25) in the CP0 Status register to toggle between modes, allowing user-mode reversal of the default big-endian ordering. PowerPC architectures employ the Little Endian (LE) bit (bit 0 in the lower 32 bits of the Machine State Register, MSR) to select modes, with the processor booting in big-endian by default but supporting equivalent performance in little-endian on modern implementations like POWER8. Switching endian modes incurs performance overhead due to the necessity of flushing caches and invalidating Translation Lookaside Buffer (TLB) entries to maintain memory consistency across the changed byte ordering. This process ensures that cached data and address translations reflect the new format but can introduce latency, particularly in multi-core systems where broadcast invalidations are required. In embedded systems, ARM processors often default to little-endian mode to ensure compatibility with x86-based software ecosystems and optimize for common toolchains. Conversely, big-endian configuration is preferred in networking applications to align directly with protocol standards like TCP/IP, reducing conversion overhead in data transmission. Endianness is typically detected and configured at boot time through firmware, such as U-Boot, where compile-time options or environment variables set the initial mode before loading the operating system. For instance, U-Boot can be built for specific endianness to match the kernel image, ensuring seamless handover during boot. Historically, early SPARC architectures were fixed in big-endian mode, but the SPARC-V9 specification introduced bi-endian support for data accesses, with instruction fetches remaining big-endian. UltraSPARC implementations extended this flexibility, allowing configurable little-endian data handling alongside PCI bus support to accommodate diverse workloads.Floating-Point and Specialized Formats

The IEEE 754 standard for binary floating-point arithmetic does not specify the byte order (endianness) for multi-byte representations, such as the 32-bit single-precision and 64-bit double-precision formats, allowing implementations to adopt either big-endian or little-endian conventions.[51] However, the standard mandates a fixed bit-level layout within the overall bit field: the sign bit occupies the most significant bit, followed by the biased exponent, and then the mantissa (fraction). This preservation of the sign-exponent-mantissa sequence within bytes ensures that, regardless of endianness, the internal structure remains consistent when bytes are reordered appropriately during data transfer or storage. In practice, big-endian is often the default for network transmission of IEEE 754 values, as seen in protocols like XDR, to promote interoperability, while little-endian dominates in many modern processors like x86.[52] A concrete illustration of endianness impact appears in the double-precision encoding of the value 1.0, which has the hexadecimal bit pattern0x3FF0000000000000 (sign bit 0, exponent 1023 in biased form 0x3FF, mantissa 0). In big-endian storage, the bytes are arranged as 3F F0 00 00 00 00 00 00, placing the sign and exponent bits in the initial bytes. In little-endian storage, the sequence reverses to 00 00 00 00 00 00 F0 3F, with the sign and exponent now in the final bytes. Without byte swapping, a big-endian system interpreting little-endian bytes would misread this as a very small positive denormalized number, approximately 3.04 × 10^{-319}, highlighting the need for explicit handling in cross-endian environments.

For variable-length data types, endianness conventions vary by format to balance compactness and portability. In ASN.1 (Abstract Syntax Notation One), used in protocols like LDAP and X.509 certificates, multi-byte integers and length fields in the Basic Encoding Rules (BER) and Distinguished Encoding Rules (DER) are encoded in big-endian order, with the most significant byte first in two's complement representation. This approach ensures unambiguous parsing across architectures, as the leading bytes indicate the value's magnitude immediately. For example, the integer 258 (hex 0x0102) is stored as bytes 01 02, facilitating sequential readability without host-specific adjustments.[53] In contrast, Google's Protocol Buffers employ little-endian ordering for both variable-length varints (encoded via base-128 with least significant group first) and fixed-length fields, optimizing for little-endian-dominant systems while requiring conversion on big-endian hosts.[54]

Historical systems introduced middle-endian variants, blending elements of big- and little-endian to suit specific hardware designs. The PDP-11 minicomputer, influential in early Unix development, treated 16-bit words as little-endian (least significant byte at lower address) but arranged 32-bit longs in a mixed order: for bytes ABCD (A most significant), storage followed C D A B, effectively little-endian within words and big-endian between words. This led to the "NUXI fold" issue, where the 32-bit representation of "UNIX" (hex 0055 004E 0049 0058) appeared as "NUXI" when bytes were misinterpreted on a big-endian system like the IBM 360. Similarly, the Honeywell Series 16 (e.g., H316) used a word-swapped big-endian scheme for 32-bit values, storing them as CDAB, which inverted the word order relative to standard big-endian while maintaining big-endian within words. These variants complicated data exchange and contributed to the eventual standardization of pure big- or little-endian in modern architectures.[12]

Specialized formats like image compression often mandate a fixed endianness to ensure file portability, irrespective of the host system's native order. The PNG (Portable Network Graphics) format specifies network byte order—big-endian—for all multi-byte integers in chunk lengths, widths, heights, and pixel data fields, such as the 16-bit sample depth in non-indexed color modes where the most significant byte precedes the least. For instance, a chunk length of 13 (hex 0x000D) is encoded as 00 0D, allowing universal decoding without endian conversion. This choice aligns PNG with network protocols and contrasts with little-endian hosts like x86, where software must swap bytes during file creation or reading to comply.[55]