Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

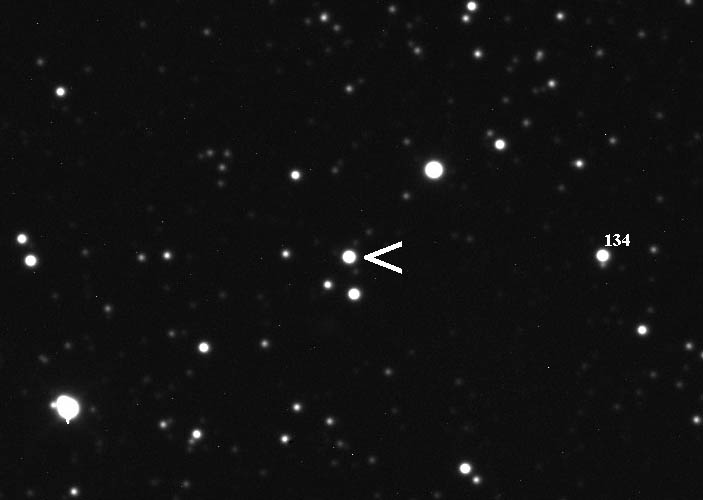

Dwarf nova

View on Wikipedia

A dwarf nova (pl. novae), or U Geminorum variable, is one of several types of cataclysmic variable star, consisting of a close binary star system in which one of the components is a white dwarf that accretes matter from its companion. Dwarf novae are dimmer and repeat more often than "classical" novae.[1]

Overview

[edit]The first one to be observed was U Geminorum in 1855; however, the mechanism was not known until 1974, when Brian Warner showed that the nova is due to the increase of the luminosity of the accretion disk.[2] They are similar to classical novae in that the white dwarf is involved in periodic outbursts, but the mechanisms are different. Classical novae result from the fusion and detonation of accreted hydrogen on the primary's surface. Current theory suggests that dwarf novae result from instability in the accretion disk, when gas in the disk reaches a critical temperature that causes a change in viscosity, resulting in a temporary increase in mass flow through the disc, which heats the whole disc and hence increases its luminosity. The mass transfer from the donor star is less than this increased flow through the disc, so the disc will eventually drop back below the critical temperature and revert to a cooler, duller mode.[3][4]

Dwarf novae are distinct from classical novae in other ways; their luminosity is lower, and they are typically recurrent on a scale from days to decades.[3] The luminosity of the outburst increases with the recurrence interval as well as the orbital period; recent research with the Hubble Space Telescope suggests that the latter relationship could make dwarf novae useful standard candles for measuring cosmic distances.[3][4]

There are three subtypes of U Geminorum star (UG):[5]

- SS Cygni stars (UGSS), which increase in brightness by 2–6 mag in V in 1–2 days, and return to their original brightnesses in several subsequent days.

- SU Ursae Majoris stars (UGSU), which have brighter and longer "supermaxima" outbursts, or "super-outbursts," in addition to normal outbursts. Varieties of SU Ursae Majoris star include ER Ursae Majoris stars and WZ Sagittae stars (UGWZ).[6]

- Z Camelopardalis stars (UGZ), which temporarily "halt" at a particular brightness below their peak; a behavior termed a "standstill".[7] They are interpreted as occupying the border between the classes of dwarf nova and the more stable nova-like variables.[8]

In addition to the large outbursts, some dwarf novae show periodic brightening known as “superhumps”. They are caused by deformations of the accretion disk when its rotation is in resonance with the orbital period of the binary.

-

AAVSO light curve of U Geminorum (SS Cygni type)

-

Light curve of eclipsing dwarf nova HT Cassiopeiae during outburst, showing eclipses and superhumps (SU Ursae Majoris type)

-

Light curve of Z Camelopardalis (Z Camelopardalis type)

References

[edit]- ^ Samus, N.N.; Durlevich, O.V. (12 February 2009). "GCVS Variability Types and Distribution Statistics of Designated Variable Stars According to their Types of Variability". Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- ^ Warner, Brian (July 1974). "Observations of Rapid Blue Variables – XIV: Z C HAMAELEONTIS". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 168 (1): 235–247. doi:10.1093/mnras/168.1.235.

- ^ a b c Simonsen, Mike (ed.). "Introduction to CVs". mindspring.com. Cataclysmic Variable Network. Archived from the original on 26 February 2008. Retrieved 17 April 2006.

- ^ a b "Calibrating Dwarf Novae". Sky & Telescope. September 2003. p. 20.

- ^ Darling, David (1 February 2007). "U Geminorum star". Daviddarling.info. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ^ Darling, David (1 February 2007). "SU Ursae Majoris star". Daviddarling.info. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ^ Stehle, R.; King, A.; Rudge, C. (May 2001). "The standstill luminosity in Z Cam systems". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 323 (3): 584–586. arXiv:astro-ph/0012379. Bibcode:2001MNRAS.323..584S. doi:10.1046/j.1365-8711.2001.04223.x. S2CID 14478251.

- ^ Osaki, Yoji (January 1996). "Dwarf-Nova Outbursts". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 108: 39. Bibcode:1996PASP..108...39O. doi:10.1086/133689.

External links

[edit]- "New Method of Estimated Dwarf Novae Distances". Spaceflight Now. 30 May 2003. Retrieved 17 April 2006.

- "SU Ursae Majoris". American Association of Variable Star Observers.

- "Amateur Astronomers and Dwarf Novae" (PDF). European Southern Observatory.

- "Activity at a glance (list of recently detected dwarf nova outbursts)". Cataclysmic Variable Network – via Google.