Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Sam Cooke.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

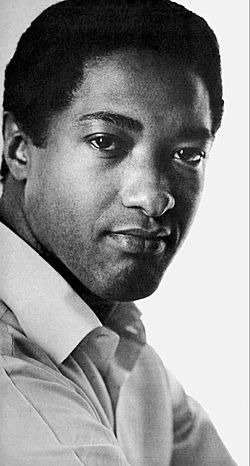

Sam Cooke

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

Not found

Sam Cooke

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

Sam Cooke (January 22, 1931 – December 11, 1964) was an American singer, songwriter, and entrepreneur who pioneered the soul genre through his smooth tenor voice and innovative fusion of gospel, rhythm and blues, and pop elements.[1][2] Born Samuel Cook in Clarksdale, Mississippi, to a Baptist minister father, he relocated with his family to Chicago as a toddler and began performing gospel as a teenager with the Soul Stirrers, adopting the stage name Sam Cooke.[2][1]

Transitioning to secular music in 1956, Cooke achieved commercial success with his debut single "You Send Me," which topped the Billboard R&B chart for six weeks and crossed over to the pop charts, establishing him as a versatile hitmaker.[1] Subsequent releases like "Chain Gang," "Wonderful World," and "Twistin' the Night Away" showcased his songwriting prowess and adaptability to emerging dance crazes, while he founded SAR Records in 1959 to gain greater control over his career and promote Black artists.[1][3]

Cooke's influence extended to civil rights, as he refused performances at segregated venues, faced death threats during Southern tours, and composed "A Change Is Gonna Come" in 1963, inspired by the March on Washington and Bob Dylan's protest songs, which became an anthem for the movement despite its posthumous release.[4][5] His death at age 33—shot by the manager of a Los Angeles motel following an altercation, officially deemed justifiable homicide—has fueled ongoing suspicions of foul play, including theories of robbery setups or retaliation linked to his business independence and activism, though no conclusive evidence has overturned the ruling.[6][7]

This table summarizes select Top 10 Hot 100 performances, drawn from verified chart data.[40] [41] Cooke's R&B chart dominance was even more pronounced, with 20 Top 10 entries, reflecting his foundational influence in that genre amid slower pop crossover gains.[40]

These releases, often compiling recent singles with new recordings, achieved modest commercial success amid the singles-driven market of the era, with later RCA efforts like Ain't That Good News incorporating socially conscious tracks such as "A Change Is Gonna Come."[132][133]

Early Life

Birth and Family Background

Samuel Cook, later known as Sam Cooke, was born on January 22, 1931, in Clarksdale, Mississippi.[8][9] He was the fifth of eight children born to Charles Cook Sr., a Baptist minister, and Annie Mae Cook.[9][10] The family relocated to Chicago, Illinois, in 1933 as part of the Great Migration of African Americans from the rural South to northern cities seeking economic opportunities.[11][12] In Chicago, Charles Cook Sr. continued his ministerial work, which immersed the children in gospel music and church activities from an early age.[1][13] The family's initial residence was at 3527 Cottage Grove Avenue in the Bronzeville neighborhood.[14]Initial Musical Exposure and Gospel Roots

Sam Cooke, born Samuel Cook on January 22, 1931, in Clarksdale, Mississippi, to Reverend Charles Cook Sr., a Baptist minister, and Annie May Cook, received his initial musical training in the gospel tradition through his family's religious practices.[15] The family, consisting of eight children, relocated to Chicago around 1933, where Cooke's father pastored a local church that emphasized vocal performance in services.[16] At age six, Cooke began singing in his father's church choir, marking his first structured exposure to music centered on gospel hymns and spirituals.[16] He soon formed a juvenile ensemble with three siblings called the Singing Children, performing gospel material in the 1930s at church events and local gatherings, which honed his early harmonic and lead vocal skills within a familial context.[17][18] By his teenage years, Cooke expanded beyond church settings by joining the Highway Q.C.'s (also styled as Teenage Highway Q.C.'s), a Chicago-based gospel quartet, in the spring of 1947, where he alternated as one of two lead singers.[19] This group represented his entry into semi-professional gospel performance, involving travel for regional appearances and emphasizing quartet dynamics that influenced his phrasing and emotional delivery.[20] These formative experiences in church choirs, sibling groups, and youth quartets established Cooke's foundational style rooted in gospel's call-and-response structures and improvisational fervor, distinct from secular influences at the time.[21]Gospel Career

Tenure with the Soul Stirrers

Sam Cooke joined the Soul Stirrers in 1950 at the age of 19, replacing R. H. Harris as the group's lead tenor vocalist after Harris departed to focus on ministry and family.[20][22] The Soul Stirrers, founded in 1926 in Texas by S. Roy Crain, had already established themselves as pioneers of the gospel quartet style, emphasizing harmonized group singing with a prominent lead voice, and had signed with Specialty Records in 1948.[23] Upon joining, Cooke initially shared lead duties with baritone Paul Foster before assuming the primary lead role, bringing a smoother, more emotive tenor that blended gospel fervor with emerging rhythmic influences.[24] During his six-year tenure from 1950 to 1956, Cooke contributed to numerous recordings for Specialty Records, elevating the group's commercial profile within the gospel market. Key tracks included "Jesus Gave Me Water" (1951), which showcased his fluid phrasing and became a staple of their repertoire, and "Touch the Hem of His Garment" (1956), noted for its intricate harmonies and Cooke's soaring improvisations.[23][20] Other significant releases from this period encompassed "Nearer to Thee," "Wonderful," and "Peace in the Valley," often performed in live settings that highlighted the group's dynamic call-and-response interplay.[25] These sessions, produced under Art Rupe at Specialty, captured Cooke's developing vocal technique, which emphasized melismatic runs and emotional depth, influencing subsequent gospel and soul artists.[26] Cooke's presence helped the Soul Stirrers maintain their status as one of gospel's premier acts, with frequent touring across the United States and recordings that sold modestly but built a devoted following in Black churches and communities.[27] By 1956, however, Cooke sought to expand beyond gospel constraints; in June of that year, he informed Rupe of his intent to record secular "popular ballads" pseudonymously while still affiliated with the group, signaling the beginning of his transition.[20] He formally departed in late 1956 or early 1957 to pursue a solo career in rhythm and blues, a move that ended his primary gospel phase but preserved his foundational influence on the Soul Stirrers' sound.[28]Key Gospel Recordings and Performances

Cooke's initial recordings with the Soul Stirrers, released on Specialty Records, established his lead vocal style characterized by smooth phrasing and emotional depth, departing from the more declarative gospel leads of predecessors like R.H. Harris. His debut single featured "Jesus Gave Me Water," recorded in 1951, an adaptation of a traditional spiritual that showcased his ability to sustain high notes and improvise melismatically, drawing crowds to the group's live appearances in black churches across the South and Midwest.[29] The B-side, "Peace in the Valley," further highlighted the ensemble's harmonies supporting Cooke's soaring tenor.[25] Subsequent sessions from 1951 to 1955 yielded tracks like "Touch the Hem of His Garment," recorded around 1956 but rooted in earlier live repertory, where Cooke conveyed narrative urgency through subtle vibrato and dynamic shifts, influencing later gospel soloists.[26] "Nearer to Thee," captured in live performances circa 1955, exemplified the group's interactive call-and-response during extended church services, with Cooke trading leads with second tenor Paul Foster to build congregational fervor.[30] These recordings, totaling over 80 sides during his tenure, were often performed at revivals and conventions, amplifying the Soul Stirrers' popularity in gospel circuits.[31] Other notable releases included "That's Heaven to Me" and "Any Day Now," both emphasizing Cooke's optimistic timbre against the group's tight rhythmic foundation, which sustained audience engagement in unamplified venues typical of the era.[25] Live renditions of these songs, undocumented in formal recordings but recounted in contemporary accounts, featured improvisational ad-libs that mirrored sermonic preaching, reinforcing the quartet's role in sustaining gospel traditions amid emerging secular influences.[32]Transition to Secular Music

Departure from Gospel and Early Secular Releases

In late 1956, while still performing as lead singer of the Soul Stirrers, Cooke recorded his first secular single, "Lovable" (backed with "Forever"), under the pseudonym Dale Cook to minimize backlash from the gospel community averse to secular pursuits.[33][34] The track, a secular adaptation of the Soul Stirrers' gospel song "Wonderful," was released by Specialty Records in early 1957 but achieved limited commercial success, peaking outside the national charts. This tentative step reflected Cooke's strategic caution, as Specialty's owner Art Rupe had expressed reluctance to promote secular material from gospel artists, prompting producer Bumps Blackwell to seek alternative distribution.[35] Cooke officially departed the Soul Stirrers in 1957, citing his ambition to enter pop music, which clashed with the group's strict gospel focus and drew criticism from purists who viewed the crossover as a betrayal of spiritual commitments.[28] Freed from gospel obligations, he signed with the fledgling Keen Records, owned by brothers Robert and John Dootsie Williams, which specialized in rhythm and blues.[35] His debut under his own name, "You Send Me" (backed with "Summertime"), was recorded at Specialty's studios but released by Keen on October 16, 1957, after Rupe declined to issue it.[36] The ballad, written by Cooke, ascended to number one on the Billboard R&B chart for six weeks and number one on the pop chart, selling over two million copies and marking one of the earliest successful bridges from gospel to mainstream pop by a Black artist.[28] Follow-up releases in 1957–1958, including "I'll Come Running Back to You" (reissued by Keen after initial Specialty gospel release) and "Love You Most of All," built on this momentum, with the former reaching number 18 on the pop chart in early 1958.[37] These early secular efforts showcased Cooke's adaptation of gospel phrasing—marked by melismatic runs and emotive delivery—to romantic themes, though they faced resistance from some gospel audiences and radio programmers wary of the genre shift.[38] Despite modest initial sales for non-hits, the period established Cooke as a viable pop contender, grossing tens of thousands in royalties by mid-1958 through Keen deals.[35]Initial Challenges in Crossover

Cooke's transition to secular music began amid resistance from his gospel roots, as he sought broader commercial opportunities beyond the church circuit. In June 1956, he informed Specialty Records owner Art Rupe of his intent to record "popular ballads" for a major label, but Rupe, focused on gospel, rebuffed the idea and later rejected demos as inauthentic for pop.[20] To test secular waters without immediate backlash, Cooke released his first pop single, "Lovable"—a secular rework of the Soul Stirrers' gospel song "Wonderful"—under the pseudonym Dale Cook in early 1957.[20][18] The pseudonym failed to conceal his identity, as fans and industry insiders quickly recognized his smooth, emotive tenor, igniting swift condemnation from the gospel community. Purists decried the shift as a moral compromise, equating secular pursuits with spiritual abandonment and fearing it invited divine judgment or career ruin for associated acts.[20][39] Soul Stirrers members, including S.R. Cruce and J.J. Farley, were dismayed, wiring Rupe to halt further releases to protect the group's sanctity and sales; Cooke was promptly ousted as lead singer, severing his primary platform.[20][18] Compounding these cultural hurdles, "Lovable" flopped commercially, highlighting the stylistic and market barriers: gospel's fervent delivery clashed with pop's smoother demands, while racial segregation confined black artists to niche "race records," limiting crossover airplay and distribution.[39] These obstacles reflected broader industry taboos against gospel-to-secular moves, positioning Cooke as a pioneer who endured ostracism to challenge entrenched norms.[18][39]Commercial Breakthrough

Major Hits and Chart Success

Cooke's transition to secular music produced rapid chart success, beginning with "You Send Me," released in September 1957, which ascended to number one on the Billboard Hot 100 for three weeks starting December 9, 1957, and also topped the R&B chart.[40] [41] The single's performance marked Cooke's emergence as a crossover artist, blending gospel-inflected soul with broad pop appeal. Over his eight-year recording career from 1957 to 1964, Cooke placed 29 singles in the Top 40 of the Billboard Hot 100, including eight in the Top 10.[40] Subsequent releases sustained this momentum. "Chain Gang," issued in July 1960, peaked at number two on the Hot 100 and number two on the R&B chart, reflecting Cooke's ability to fuse rhythmic work-song elements with commercial accessibility.[40] [41] "Wonderful World," released in April 1960, reached number 12 on the Hot 100 despite stronger R&B performance at number two, underscoring persistent racial barriers in pop chart dominance for Black artists during the era.[40] In 1961, "Cupid" climbed to number 17 on the Hot 100, bolstered by its melodic simplicity and romantic theme.[40] Cooke's 1962 output included "Twistin' the Night Away," which hit number nine on the Hot 100 and number one on R&B, capitalizing on the twist dance craze, and "Bring It On Home to Me," peaking at number 13 on the Hot 100 with a duet-style arrangement.[40] [41] "Another Saturday Night" in 1963 achieved number 10 on the Hot 100 and number one on R&B, highlighting Cooke's songwriting prowess in capturing universal social observations.[40] [41] Posthumous releases after Cooke's death in December 1964 extended his chart legacy. "Shake" reached number seven on the Hot 100 in 1965, while "A Change Is Gonna Come," though only number 31 on the Hot 100, attained number nine on R&B and later gained enduring acclaim for its civil rights resonance, though its modest initial pop showing illustrates the era's conservative programming preferences.[40] [41]| Song Title | Release Year | Hot 100 Peak | R&B Peak |

|---|---|---|---|

| You Send Me | 1957 | 1 | 1 |

| Chain Gang | 1960 | 2 | 2 |

| Twistin' the Night Away | 1962 | 9 | 1 |

| Shake (posthumous) | 1965 | 7 | 2 |

| Another Saturday Night | 1963 | 10 | 1 |

Formation and Operation of SAR Records

In 1959, Sam Cooke established SAR Records in Los Angeles with his longtime associate and music publisher J.W. Alexander and road manager S. Roy Crain, the latter a former member of the Soul Stirrers gospel group.[42][43] The label's name derived from the initials of its founders—Sam, Alex (Alexander), and Roy (Crain)—and operated from addresses including 3710 West 27th Street before relocating to 6425 Hollywood Boulevard by 1961.[44][45] Motivated by frustrations with exploitative contracts at major labels, Cooke sought greater control over production, publishing, and artist development for Black musicians, particularly in gospel and emerging rhythm and blues genres, while distributing secular recordings through affiliated imprints like Derby.[46][47] SAR's initial focus was on gospel acts, with its debut single being the Soul Stirrers' "Wade in the Water" backed with "He Cares," released in 1959 and produced by Cooke, who also contributed backing vocals on select tracks.[44][48] The label expanded to secular R&B, signing artists such as the Sims Twins, whose Cooke-penned "Soothe Me" reached number 44 on the Billboard Hot 100 in October 1961, marking SAR's biggest commercial hit.[47] Other notable releases included recordings by the Womack Brothers (later the Valentinos), Johnnie Taylor, and the Valentinos, with Cooke serving as producer, songwriter, and occasional arranger to nurture talent transitioning from gospel roots.[49][47] Between 1959 and 1965, SAR issued approximately 50 singles and four long-playing albums, emphasizing self-contained operations that integrated recording, promotion, and booking to retain royalties and artistic autonomy for performers.[44][50] Although Cooke primarily recorded for RCA Victor during this period, he produced two tracks for SAR—"That's Heaven to Me" (a solo gospel rendition) and an unreleased session item—which remained vaulted until post-2001 compilations.[47] The label's independent model challenged industry norms by prioritizing Black ownership and vertical integration, but it faced distribution hurdles and modest sales outside gospel circuits, ceasing operations shortly after Cooke's death on December 11, 1964.[46][47] A 1994 ABKCO Records anthology, Sam Cooke's SAR Records Story 1959–1965, later documented 46 tracks from the catalog, highlighting its role in bridging gospel and soul.[48]Artistic Style

Vocal Technique and Range

Sam Cooke's vocal technique was rooted in his gospel training with the Soul Stirrers, where he developed a light, agile tenor voice capable of soaring leads and intricate harmonies, emphasizing emotional delivery through melismatic runs and dynamic phrasing.[51] His timbre, often described as honeyed and intimate, allowed seamless transitions between chest voice and falsetto, enabling expressive storytelling in both sacred and secular contexts.[52] This versatility stemmed from rigorous practice in quartet singing, fostering precise pitch control and breath support that sustained long, sustained notes without strain.[53] His documented vocal range extended from D2 to G5, spanning approximately 3.4 octaves, as evidenced by analyses of recordings like "Chain Gang," which reaches lows near D2 and highs up to G4.[54] In gospel tracks such as those with the Soul Stirrers, Cooke frequently accessed upper tenor registers (C3 to C5) with a bright, ringing quality, while secular hits like "A Change Is Gonna Come" showcased controlled falsetto extensions into the fifth octave for dramatic effect.[55] This range, combined with subtle vibrato and rhythmic flexibility, distinguished him from contemporaries, bridging gospel fervor with soul's restraint.[56] Cooke's technique evolved post-transition to secular music around 1956, incorporating smoother glissandi and softer attacks influenced by pop crooners, yet retaining gospel-derived inflections like bent notes and improvisational fills for authenticity.[57] Vocal coaches note his efficient mix voice usage, blending registers to maintain even tone across his range without pushing, which preserved vocal health amid intensive touring.[58] Such control was pivotal in live performances, where he adapted dynamically to audiences, amplifying emotional resonance through subtle volume swells rather than raw power.[59]Songwriting Approach and Innovations

Sam Cooke's songwriting drew heavily from direct observation of everyday life and human experiences, which he described as the core of his technique. In a 1963 interview with Dick Clark, Cooke stated, "I think the secret is really observation... you can always write something that people will understand," positioning himself as a reporter-like figure capturing relatable realities rather than abstract emotions.[60] For instance, witnessing a chain gang working roadside inspired "Chain Gang" (released October 1960), incorporating authentic grunts and vivid imagery to evoke labor's toil.[61] This grounded method produced simple, singable structures designed for audience engagement, often with participatory choruses that mirrored gospel call-and-response traditions adapted to secular contexts.[60] His compositional process emphasized natural flow and emotional build-up, starting compositions slowly before escalating to intense rhythms. Cooke explained, "I write songs that start slowly and then work in little by little to this pounding beat. That is where the excitement is," retaining gospel-derived fervor while secularizing themes of love and longing.[62] Lyrics adopted a conversational tone, making them feel like intimate dialogue—evident in hits like "Bring It On Home to Me" (1962, peaked at No. 13 on Billboard Hot 100), which he penned spontaneously in a limousine using a reading lamp.[63] This approach yielded effortless freshness in tracks such as "Wonderful World" (1960) and "Cupid" (1961), blending personal anecdotes with universal appeal.[62] Cooke's innovations lay in pioneering soul songwriting by fusing gospel's emotive depth with rhythm and blues' accessibility, creating a hybrid form that facilitated crossover success for Black artists. Alongside figures like Ray Charles, he reinvented R&B into soul through self-authored hits that topped pop charts, such as "You Send Me" (1957, his first No. 1 single), which integrated gospel tension-release patterns into pop frameworks.[62] By writing prolifically—often collaboratively but retaining primary credit—he achieved rare artistic autonomy, later exemplified in "A Change Is Gonna Come" (recorded 1963, released 1965), a civil rights anthem born from personal encounters with Southern racism and Bob Dylan's influence, introducing subtle social commentary into mainstream fare.[63] This self-reliant model, uncommon for the era, influenced subsequent generations by demonstrating how observational, genre-blending composition could yield both commercial viability and cultural resonance.[60]Business Ventures

Pursuit of Financial Independence

Cooke co-founded KAGS Music, his publishing company, in January 1959 with business partners J.W. Alexander and Roy Crain, naming it after their initials (K for Crain, A for Alexander, G for a mutual associate, and S for Cooke).[2] This venture enabled him to retain ownership of songwriting royalties, diverging from the standard practice where artists ceded publishing rights to labels or external firms.[64] By controlling publishing, Cooke secured mechanical and performance royalties directly, a rare achievement for Black musicians in an era dominated by white-owned industry structures that often exploited minority talent through unfavorable contracts.[65] Simultaneously, Cooke established SAR Records in 1959 as an independent label to produce and release his own recordings alongside those of other artists, such as the Soul Stirrers and R&B acts like Johnnie Taylor.[66] SAR functioned as a mechanism for vertical integration, allowing Cooke to oversee production, artist development, and initial distribution while negotiating deals with major labels like RCA Victor for broader release—later routing his output through a subsidiary, Tracey Records, to maintain creative and financial oversight.[2] This structure minimized reliance on external managers and labels, which Cooke viewed as extractive; for instance, he produced over 60 sides for SAR between 1959 and 1965, retaining master rights and a larger share of profits compared to his earlier Keen Records deal.[48] Cooke's initiatives positioned him as the first prominent Black artist to own both a publishing imprint and a record label, predating similar efforts by figures like Berry Gordy at Motown.[67] These entities generated revenue streams beyond performance fees, including licensing and sub-publishing deals, fostering long-term financial autonomy amid racial barriers in the music business.[68] However, SAR's operations faced logistical hurdles, such as limited distribution networks for independent Black-owned labels, which constrained scalability until Cooke's death in 1964 led to its absorption by Allen Klein's ABKCO.[66] Despite these challenges, the model exemplified Cooke's strategic emphasis on equity ownership over mere hit-making, influencing subsequent artist-entrepreneurs seeking to circumvent industry gatekeepers.[65]Disputes with Managers and Labels

Cooke experienced tensions with Specialty Records owner Art Rupe following the release of "You Send Me" in 1957, as Rupe disapproved of its pop-oriented production and ballad style, which deviated from the label's gospel focus.[69] Rupe granted Cooke and producer Bumps Blackwell a release from their contract, allowing them to depart for Keen Records with the master recording of "You Send Me," which became a number-one R&B hit.[70] This split highlighted Cooke's push for artistic control in secular music, contrasting Specialty's expectations for his Soul Stirrers work.[20] Upon signing with RCA Victor in January 1960, Cooke secured an unusual agreement retaining copyrights to his compositions while RCA handled distribution and advances, but disputes arose over underreported royalties and sales figures.[66] Cooke grew distrustful of RCA's accounting practices, prompting demands for an independent audit to verify owed payments, amid broader frustrations with the label's marketing decisions.[66] In 1963, Cooke hired accountant Allen Klein as manager for Kags Music and SAR Records to address these issues; Klein's audit uncovered approximately $110,000 in back royalties from RCA, leading to a renegotiated three-year contract (with a two-year option) that advanced $100,000 annually and established Tracey Ltd. for Cooke to own his masters, with RCA covering production costs in exchange for distribution rights.[71] [66] However, by late 1964, associates reported Cooke's dissatisfaction with Klein's handling of affairs, with indications he intended to terminate the management agreement prior to his death.[71] These conflicts underscored Cooke's broader quest for financial autonomy, exemplified by founding SAR Records in 1957 with J.W. Alexander and Kags Music publishing, to retain ownership amid industry practices favoring labels over artists.[47]Personal Life

First Marriage and Divorce

Sam Cooke married singer and dancer Dolores Elizabeth Milligan, who performed under the stage name Dee Dee Mohawk, on October 19, 1953, in Chicago, Illinois.[72][73] The couple had no children together, though Cooke had previously fathered a daughter, Linda, out of wedlock with his high school sweetheart Barbara Campbell in 1951.[18] During their marriage, Cooke transitioned from gospel music with the Soul Stirrers to secular rhythm and blues, achieving early hits like "Lovable" under the pseudonym Dale Cooke to avoid alienating his religious fanbase.[12] The marriage deteriorated amid Cooke's increasing fame, frequent touring, and reported infidelities.[74] Cooke later stated of the split, "We just couldn't make it and we decided to call it quits."[75] The couple separated and pursued a contentious divorce process, finalizing it on November 15, 1957.[72] Mohawk retained her maiden name and relocated to Fresno, California, after the proceedings.[73] Despite the acrimony, Cooke and Mohawk maintained an amicable relationship post-divorce, as evidenced by his decision to cover her funeral expenses following her death in a car accident on March 22, 1959.[12][75]Second Marriage and Family

Sam Cooke married Barbara Campbell, a childhood acquaintance from Chicago whom he had known since their teenage years, on October 11, 1959, at her grandmother's home on Ellis Park in Chicago.[76] The ceremony was officiated by Cooke's father, Reverend Charles Cook, who reportedly disapproved of the union despite performing it.[77] Campbell, born in 1935, had previously been involved with Cooke; their daughter Linda was born on April 25, 1953, prior to the marriage.[78] The couple had two additional children: Tracy, born in 1959, and Vincent, born in 1961.[79] The family resided primarily in Los Angeles, where Cooke pursued his career, establishing a household that included domestic staff amid his rising fame.[20] In June 1963, tragedy struck when 18-month-old Vincent drowned in the family's swimming pool, an event that deeply affected the household.[77][78] Linda later pursued a music career, recording as Linda Womack and collaborating with family members in the industry.[78]Extramarital Relationships

Cooke's marriage to Barbara Campbell, which began on October 18, 1959, was strained by mutual infidelities throughout its duration.[80] Cooke engaged in numerous extramarital relationships, earning a reputation as a prolific womanizer who frequently sought out prostitutes.[80][81] His longtime associate and manager Bumps Blackwell characterized this pattern bluntly, stating that Cooke "would walk past a good girl to get to a whore."[80] Barbara Cooke was fully aware of her husband's serial cheating but reciprocated with her own affair involving a local bartender, who was observed wearing Cooke's watch and ring at the singer's funeral on December 18, 1964.[80][81] These parallel infidelities exacerbated tensions in the marriage, which already faced pressures from Cooke's demanding touring schedule and the 1963 drowning death of their infant son Vincent.[82] While specific names of Cooke's ongoing mistresses remain largely undocumented in primary accounts, his behavior reflected a broader disregard for marital fidelity amid his rising fame in the early 1960s.[80] One documented instance of his promiscuity occurred on December 10, 1964, when Cooke picked up 22-year-old Elisa Boyer at a Los Angeles nightclub, leading to a brief sexual encounter at the Hacienda Motel that precipitated the night's fatal events—though this was not an established affair.[81] The couple's reciprocal betrayals foreshadowed further scandals in Barbara's life after Cooke's death, including her rapid remarriage to his protégé Bobby Womack.[80]Controversies

Infidelities and Personal Conduct

Cooke's first marriage to Dolores "Dee Dee" Mohawk, contracted in 1953, overlapped with the start of his longstanding relationship with Barbara Campbell, who gave birth to their daughter Linda that same year out of wedlock.[20] [78] This affair contributed to the dissolution of his union with Mohawk, whom he divorced in 1958 before marrying Campbell in Chicago on October 18, 1959.[77] During his second marriage, Cooke maintained a pattern of serial infidelity, described by contemporaries and biographers as driven by a voracious libido and chronic womanizing.[77] [83] He fathered several illegitimate children amid these extramarital relationships, which strained his family life and were known to Campbell, who tolerated them while engaging in her own affair with a local bartender.[78] [81] Cooke's conduct reflected a broader disregard for marital fidelity, prioritizing personal gratification over domestic stability, though no public admissions or legal repercussions from these liaisons were documented during his lifetime.[84] Associates noted Cooke's charm often facilitated these encounters, but his behavior drew private criticism within his inner circle for its recklessness, particularly as it intersected with his rising public persona as a moral and musical figurehead.[85] Despite this, accounts from those close to him, including Campbell, emphasized that his infidelities were an open secret rather than sources of overt scandal, overshadowed by his professional achievements until the circumstances of his death amplified scrutiny.[80]Professional and Ethical Criticisms

Cooke's decision to transition from gospel to secular music in the mid-1950s elicited significant backlash from segments of the gospel community, who viewed it as a betrayal of sacred traditions for commercial gain. As lead singer of the Soul Stirrers, Cooke had helped popularize gospel with emotive performances that drew young audiences, but his 1957 release of "You Send Me" under the pseudonym Dale Cooke initially masked his identity to mitigate anticipated disapproval.[86] Upon revelation, critics within gospel circles accused him of blurring sacred and profane boundaries, prioritizing worldly success over spiritual integrity.[87] This sentiment echoed broader tensions, similar to those faced by Ray Charles, where secularization was equated with moral compromise.[88] Despite the opposition, Cooke persisted, achieving crossover success that some gospel purists decried as abandoning his roots.[89] Professionally, disputes arose during his early career shift from Specialty Records, where label head Art Rupe objected to the secular direction of recordings produced with Bumps Blackwell, leading to their departure amid contractual tensions.[62] Rupe's dissatisfaction stemmed from Cooke's pivot away from expected gospel material, resulting in Blackwell negotiating control of session tapes and sparking litigation over royalties and ownership.[62] These conflicts highlighted ethical questions about artist autonomy versus label expectations in an era of rigid genre boundaries, though Cooke maintained he sought broader expression without disavowing his gospel foundation. No widespread accusations of exploitative practices emerged against Cooke himself; instead, his efforts to establish SAR Records in 1961 aimed to counter industry exploitation of Black artists by retaining publishing and production control.[90]Death

Events at the Hacienda Motel

On December 11, 1964, shortly after 2:00 a.m., Sam Cooke and a woman identified as Elisa Boyer checked into Room 32 at the Hacienda Motel in Los Angeles, California, under the name "Mrs. Booker".[6] [91] An argument soon erupted in the room, during which Boyer fled the premises, taking Cooke's clothing, including his pants containing approximately $108 in cash, and leaving him partially undressed.[92] [93] Cooke, wearing only a sports coat and shoes over his underwear, pursued Boyer barefoot through the motel's parking lot and burst into the manager's office apartment, where he confronted Bertha Lee Franklin, the 51-year-old motel manager, demanding to know the woman's location.[94] [6] Franklin, who was with another employee, retrieved a .22-caliber pistol from her purse after Cooke allegedly grabbed her and demanded information, then fired a single shot into his chest at close range around 3:00 a.m.[92] [91] Cooke reportedly exclaimed, "Lady, you shot me," before staggering out of the office, collapsing in the motel's front parking lot near his car, where he succumbed to the wound from massive internal bleeding.[94] [93] Franklin immediately telephoned the Los Angeles Police Department at approximately 3:10 a.m. to report the shooting, claiming self-defense after Cooke attacked her.[6] Officers arrived minutes later and found Cooke's body, clad only in the aforementioned attire, with Boyer located nearby at a public telephone booth where she had called a taxi.[92] [91] The scene yielded the pistol, registered to Franklin, along with spent casings, though initial reports noted no signs of forced entry into the room or overt struggle beyond the office altercation.[6]Official Ruling and Inquest

The coroner's inquest into Sam Cooke's death was convened on December 16, 1964, five days after the shooting at the Hacienda Motel, and presided over by Los Angeles County Coroner Thomas Noguchi.[95] The proceedings involved testimony from key witnesses, including motel manager Bertha Franklin, who stated that Cooke had burst into her office partially clothed, assaulted her, and threatened her life after demanding the whereabouts of Elisa Boyer, leading her to fire a single .22-caliber shot in self-defense from a distance of approximately three feet.[6] Franklin's account was corroborated by the motel's night auditor, who reported hearing commotion and Cooke demanding Boyer.[80] A seven-member coroner's jury reviewed the evidence, including the autopsy report which confirmed Cooke died from a gunshot wound to the chest penetrating the heart, with no other significant injuries noted, and a toxicology report indicating a blood alcohol level of 0.14 percent—above the legal limit for intoxication at the time.[92] After deliberating for just 15 minutes, the jury returned a verdict of justifiable homicide, determining that Franklin acted in reasonable self-defense against an aggressor who posed an immediate threat.[96] This ruling absolved Franklin of criminal liability and prompted authorities to close the case without further investigation or charges.[7] The inquest's brevity and reliance on witness testimonies from Franklin and Boyer—who claimed Cooke had assaulted her earlier—drew immediate scrutiny from Cooke's family and attorney, though no appeals overturned the official findings.[97] Noguchi's office upheld the verdict based on the physical evidence aligning with self-defense, including the bullet's trajectory consistent with Franklin's positioning behind her desk.[80]Alternative Theories and Investigations

Alternative theories regarding Sam Cooke's death on December 11, 1964, primarily stem from inconsistencies in witness testimonies and physical evidence reported at the scene of the Hacienda Motel shooting. Bertha Franklin, the motel manager who fired the fatal .22-caliber shot into Cooke's chest, claimed Cooke attacked her after bursting into the motel's office naked and demanding $5,000 stolen by Elisa Boyer, the woman he had brought to the motel. However, police found minimal blood in the office despite Franklin's account of a violent struggle, and Cooke's body showed facial bruises consistent with a beating but no defensive wounds on his hands.[92] [7] Furthermore, Franklin's unregistered handgun bore no fingerprints, and she failed to call authorities immediately, only doing so after Bartley Orlando Crum, a motel bartender, arrived and summoned police around 3:00 a.m.[7] These gaps have led skeptics, including singer Etta James—who viewed the body and described Cooke's head injuries as severe enough to nearly sever it from his shoulders—to question whether the altercation occurred as described or if Cooke was killed elsewhere and his body placed at the motel.[98] [80] One prominent theory posits a robbery setup involving Boyer and Franklin, portraying the incident as a "honeytrap" targeting Cooke's cash—he had withdrawn $5,000 earlier that evening for a business deal. Boyer, who fled the motel with Cooke's clothing and money, was arrested on prostitution charges days later and in 1979 convicted of second-degree murder in an unrelated shooting, bolstering claims of her criminal background.[92] Proponents argue Franklin, a former madam with a criminal record, participated to steal from Cooke, a high-profile figure known for carrying large sums, and shot him only after he pursued Boyer.[99] This view aligns with empirical details like the absence of blood spatter in Room 49, where Cooke and Boyer were registered, suggesting no prolonged fight there before he confronted Franklin.[7] However, no direct evidence, such as financial trails or confessions, substantiates coordinated theft beyond speculation fueled by the women's inconsistent statements—Boyer initially claimed kidnapping, later recanting.[92] Broader conspiracy theories link Cooke's death to organized crime pressures on his independent music empire, particularly KRC Records (later SAR) and his control over publishing rights, which generated royalties exceeding $100,000 annually by 1964. Mob figures allegedly sought to infiltrate Black-owned labels in Los Angeles, and Cooke's refusal to cede control—coupled with disputes over song rights—positioned him as a target.[100] Allen Klein, Cooke's manager who later acquired his catalog, has been implicated in some accounts for potential motives tied to financial gains post-death, though no forensic links exist.[101] Similarly, theories tie the killing to Cooke's civil rights activism, including his financial support for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and friendships with figures like Muhammad Ali and Malcolm X, suggesting suppression of a rising Black entrepreneur challenging industry norms.[99] These narratives, echoed in documentaries and fan discussions, lack corroborative evidence like witness corroboration or ballistics tying third parties, relying instead on Cooke's documented business autonomy and the era's racial tensions.[102] Post-1964 investigations have yielded no overturn of the coroner's inquest ruling of justifiable homicide, conducted December 16, 1964, which accepted Franklin's self-defense claim without charging her due to perceived threat from Cooke's aggression.[103] Independent probes, such as those in Peter Guralnick's 2005 biography Dream Boogie, scrutinize timelines and motives but conclude discrepancies arise from panic rather than conspiracy, citing autopsy confirmation of the chest wound as instantly fatal at close range (2-3 feet).[104] A 2015 biopic pitch framed the death as a "murder investigation," highlighting unresolved questions like why Cooke registered under a pseudonym and drove to a seedy motel despite upscale alternatives.[104] Despite persistent doubts—fueled by Franklin's 1967 death from pneumonia and Boyer's evasion of further scrutiny—no new forensic evidence, such as re-examined ballistics or DNA from preserved items, has emerged to validate alternatives, leaving theories as interpretive rather than empirically proven.[105][106]Legacy

Influence on Soul and Popular Music

Sam Cooke is widely regarded as a pioneer of soul music, credited with bridging gospel traditions and secular R&B through his emotive vocal delivery and songwriting.[107] His transition from gospel performances with the Soul Stirrers in the early 1950s to secular hits like "You Send Me," released in 1957 and topping the Billboard Hot 100 for six weeks, exemplified this fusion, introducing gospel-influenced passion to broader pop audiences.[56] This approach laid foundational elements for soul as a distinct genre, characterized by expressive phrasing and rhythmic intensity derived from church music.[108] Cooke's innovations extended to popular music by emphasizing artistic control and crossover appeal, as seen in his establishment of SAR Records in 1961 to nurture emerging Black artists and retain publishing rights.[109] Songs such as "Chain Gang" (1960, peaking at #2 on the Hot 100) and "Twistin' the Night Away" (1962, #9) demonstrated his ability to blend narrative storytelling with infectious rhythms, influencing the commercialization of soul-infused pop.[107] His posthumous release "A Change Is Gonna Come" (1964) further solidified soul's emotional depth, becoming a template for socially conscious ballads in the genre.[56] Numerous artists have cited Cooke as a direct influence, including Otis Redding, who emulated his vocal dynamics; Marvin Gaye, who adopted similar smooth transitions; and Aretha Franklin, who toured with him and praised his interpretive style.[56] Al Green and Stevie Wonder also drew from Cooke's gospel-rooted phrasing, while rock figures like Rod Stewart and Mick Jagger incorporated his phrasing into their deliveries.[21] This legacy is evident in the enduring covers of his catalog, from Al Green's renditions to modern interpretations by Bruno Mars, underscoring Cooke's role in shaping soul's evolution into contemporary R&B and pop.[108]Civil Rights Involvement and Contemporary Critiques

Sam Cooke engaged in civil rights activism through personal stands against segregation and his music, though his efforts were more individualistic than organizational compared to leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. In 1963, he refused to perform at segregated venues, marking an early instance of civil disobedience by a prominent Black entertainer that pressured promoters to integrate audiences.[110] He associated with key figures including Malcolm X, Muhammad Ali (then Cassius Clay), and Jim Brown, convening in informal gatherings to discuss racial justice amid the era's tensions.[111] A pivotal incident occurred on October 8, 1963, in Shreveport, Louisiana, when Cooke and his entourage were denied rooms at a Holiday Inn despite a reservation, due to the establishment's whites-only policy. Protesting the discrimination, Cooke and three band members were arrested later that evening for disturbing the peace after honking their car horn loudly downtown.[112][113] This event, coupled with viewing the March on Washington and hearing Bob Dylan's "Blowin' in the Wind," inspired Cooke to record "A Change Is Gonna Come" in December 1963.[114] Released on his album Ain't That Good News in February 1964 and as a single posthumously in December 1964, the song expressed hope amid racial strife and emerged as an unofficial anthem for the movement, evoking resilience against barriers like "a long, a long time ago" exclusions.[4] Contemporary analyses highlight tensions in Cooke's legacy, balancing commercial crossover success with activism. Scholar Mark Anthony Neal describes his early hits like "You Send Me" as positioning him as a "safe Negro" for white audiences, yet argues his broad appeal rendered him potentially "the most dangerous" advocate by bridging racial divides.[115] Dramatizations, such as in the 2020 film One Night in Miami, fictionalize Malcolm X critiquing Cooke for prioritizing pop appeal over explicit protest lyrics, prompting Cooke to reveal his nascent civil rights song—a portrayal rooted in their real friendship but amplified for narrative effect.[116] Some critiques note initial censorship of racial references in "A Change Is Gonna Come" to preserve marketability, suggesting Cooke's integrationist approach risked diluting radical calls for change, though his economic independence via self-publishing challenged industry exploitation of Black artists.[115] These views underscore an evolving assessment: Cooke's activism, while not frontline militant, advanced cultural integration and inspired persistence, influencing legislation like the Civil Rights Act of 1964.[4]Posthumous Recognition and Honors

Cooke was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1986 as part of its inaugural class of performers.[117] In 1987, he received induction into the Songwriters Hall of Fame, recognizing his contributions as a composer.[15] In 1994, Cooke was posthumously awarded a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 7051 Hollywood Boulevard.[118] He earned the Rhythm & Blues Foundation's first Pioneer Award in 1999, honoring his foundational role in the genre, alongside the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award from the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences that same year.[2][119] Cooke's recordings received separate recognition through the Grammy Hall of Fame, with "You Send Me" inducted in 1998 and "A Change Is Gonna Come" in 2000 for their historical and artistic significance.[120] In 2013, he was enshrined in the National Rhythm & Blues Hall of Fame.[121]Modern Interpretations and Media Portrayals

In recent decades, Sam Cooke's life and death have been reexamined through documentaries that emphasize his civil rights activism and question the official account of his 1964 shooting. The 2019 Netflix production ReMastered: The Two Killings of Sam Cooke posits that Cooke's outspoken opposition to racial injustice, including his funding of voter registration drives and associations with figures like Muhammad Ali, may have provoked powerful interests, framing his death as potentially linked to broader political threats rather than a random altercation.[122] [123] This interpretation contrasts with the 1965 inquest's finding of justifiable homicide by motel manager Bertha Franklin, highlighting how modern narratives often amplify conspiracy angles amid skepticism toward mid-20th-century institutional rulings on Black celebrities' deaths.[124] Earlier portrayals, such as the 2001 Grammy-winning Sam Cooke: Legend, focus more affirmatively on his musical evolution from gospel with the Soul Stirrers to secular hits, drawing on interviews with family and collaborators to underscore his role in pioneering soul's emotive phrasing and crossover appeal without delving deeply into death controversies.[125] [126] Subsequent films like Lady You Shot Me: The Life and Death of Sam Cooke (2017) and The Mysterious Life and Death of Sam Cooke (2021) blend biography with forensic speculation, citing inconsistencies in witness testimonies and Franklin's financial motives, though these remain unsubstantiated by new empirical evidence and reflect ongoing cultural distrust in official narratives involving racial dynamics.[127] [128] Contemporary musical interpretations revive Cooke's catalog through covers and stylistic emulation, affirming his foundational influence on soul-derived genres. Artists like Leon Bridges have drawn direct comparisons for their smooth, gospel-inflected tenor, with Bridges covering "Bring It On Home to Me" in live sets that echo Cooke's phrasing.[129] Modern tributes include G-Eazy's sampling of "A Change Is Gonna Come" in 2015's "Opportunity Cost," repurposing its civil rights urgency for hip-hop introspection, while Aretha Franklin's estate collaborations in the 2020s highlight Cooke's enduring melodic templates in R&B production.[130] Recent analyses, such as Mark Anthony Neal's 2024 essay, interpret Cooke's politics as pragmatic rather than radical, crediting his self-owned publishing and SAR Records for modeling Black economic independence that prefigured hip-hop entrepreneurship, though some critiques note his initial reluctance on overt activism until personal encounters, like a 1963 Shreveport hotel denial, catalyzed anthems like "A Change Is Gonna Come."[88] [111] These portrayals collectively position Cooke as a multifaceted innovator whose commercial savvy and vocal innovation transcend his truncated career, yet they underscore interpretive tensions: mainstream media often romanticizes his martyrdom, while truth-oriented reviews caution against unsubstantiated theories eclipsing verifiable achievements like his 29 Billboard Hot 100 entries and soul's genre codification.[107][131]Discography

Studio Albums

Sam Cooke's studio albums, released between 1958 and 1964, featured a blend of his hit singles, original compositions, and interpretations of blues and pop standards, marking his evolution from R&B crooner to soul pioneer. Initially issued by Keen Records, his output shifted to RCA Victor following his 1960 contract, emphasizing fuller arrangements and mature themes.[132][133]| Title | Release Year | Label |

|---|---|---|

| Songs by Sam Cooke | 1958 | Keen |

| Encore | 1958 | Keen |

| Tribute to the Lady | 1959 | Keen |

| Cooke's Tour | 1960 | RCA Victor |

| My Kind of Blues | 1961 | RCA Victor |

| Twistin' the Night Away | 1962 | RCA Victor |

| Night Beat | 1963 | RCA Victor |

| Mr. Soul | 1963 | RCA Victor |

| Ain't That Good News | 1964 | RCA Victor |