Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

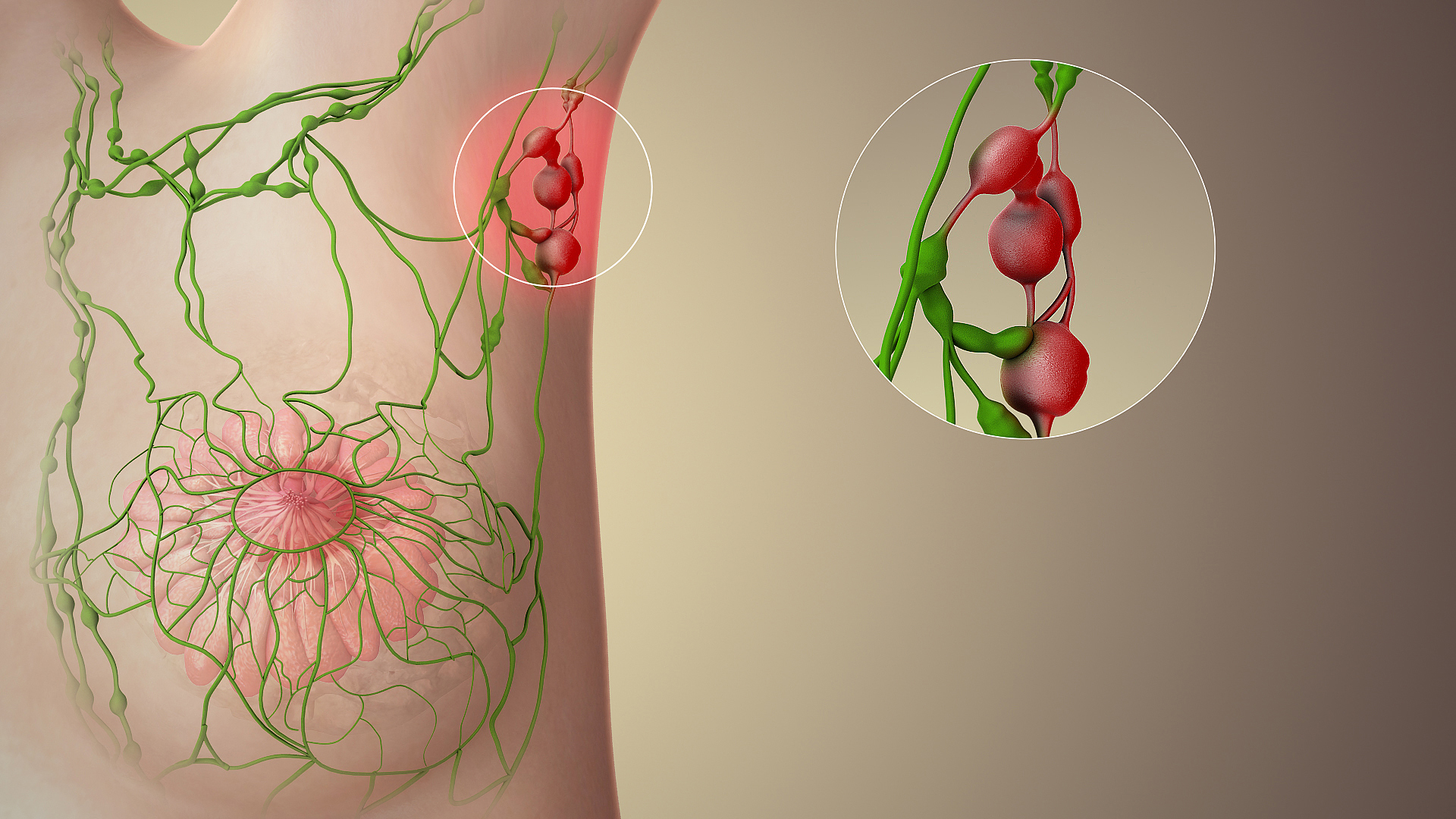

Sentinel lymph node

View on Wikipedia

The sentinel lymph node is the hypothetical first lymph node or group of nodes draining a cancer. In case of established cancerous dissemination it is postulated that the sentinel lymph nodes are the target organs primarily reached by metastasizing cancer cells from the tumor.

The sentinel node procedure (also termed sentinel lymph node biopsy or SLNB) is the identification, removal and analysis of the sentinel lymph nodes of a particular tumour.[1]

Physiology

[edit]The spread of some forms of cancer usually follows an orderly progression, spreading first to regional lymph nodes, then the next echelon of lymph nodes, and so on, since the flow of lymph is directional, meaning that some cancers spread in a predictable fashion from where the cancer started. In these cases, if the cancer spreads it will spread first to lymph nodes (lymph glands) close to the tumor before it spreads to other parts of the body. The concept of sentinel lymph node surgery is to determine if the cancer has spread to the very first draining lymph node (called the "sentinel lymph node") or not. If the sentinel lymph node does not contain cancer, then there is a high likelihood that the cancer has not spread to any other area of the body.[2]

Uses

[edit]The concept of the sentinel lymph node is important because of the advent of the sentinel lymph node biopsy technique, also known as a sentinel node procedure. This technique is used in the staging of certain types of cancer to see if they have spread to any lymph nodes, since lymph node metastasis is one of the most important prognostic signs. It can also guide the surgeon to the appropriate therapy.[3]

There are various procedures entailing the sentinel node detection:

- Preoperative planar lymphoscintigraphy

- Preoperative planar lymphoscintigraphy in conjunction with SPECT/CT [single photonemission CT (SPECT) with a low-dose CT][4][5]

- Intraoperative visual blue dye detection

- Intraoperative fluorescence detection (fluorescence image-guided surgery)

- Intraoperative gamma probe/Geiger meter-detection

- Preoperative or intraoperative super paramagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles injection, detection by using Sentimag instrument[6][7]

- Postoperative scintigraphy of main specimen with planar acquisition

In everyday clinical activity, entailing sentinel node detection and sentinel lymph node biopsy, it is not required to include all different techniques listed above. In skilled hands and in a center with sound routines, one, two or three of the listed methods can be considered sufficient.

To perform a sentinel lymph node biopsy, the physician performs a lymphoscintigraphy, wherein a low-activity radioactive substance is injected near the tumor. The injected substance, filtered sulfur colloid, is tagged with the radionuclide technetium-99m. The injection protocols differ by doctor but the most common is a 500 μCi dose divided among 5 tuberculin syringes with 1/2 inch, 24 gauge needles.[citation needed] In the UK 20 megabecquerels of nanocolloid is recommended.[8] The sulphur colloid is slightly acidic and causes minor stinging. A gentle massage of the injection sites spreads the sulphur colloid, relieving the pain and speeding up the lymph uptake. Scintigraphic imaging is usually started within 5 minutes of injection and the node appears from 5 min to 1 hour. This is usually done several hours before the actual biopsy. About 15 minutes before the biopsy the physician injects a blue dye in the same manner. Then, during the biopsy, the physician visually inspects the lymph nodes for staining and uses a gamma probe or a Geiger counter to assess which lymph nodes have taken up the radionuclide. One or several nodes may take up the dye and radioactive tracer, and these nodes are designated the sentinel lymph nodes. The surgeon then removes these lymph nodes and sends them to a pathologist for rapid examination under a microscope to look for the presence of cancer.

A frozen section procedure is commonly employed (which takes less than 20 minutes), so if neoplasia is detected in the lymph node a further lymph node dissection may be performed. With malignant melanoma, many pathologists eschew frozen sections for more accurate "permanent" specimen preparation due to the increased instances of false-negative with melanocytic staining.

Clinical advantages

[edit]There are various advantages to the sentinel node procedure. First and foremost, it decreases lymph node dissections where unnecessary, thereby reducing the risk of lymphedema, a common complication of this procedure. Increased attention on the node(s) identified to most likely contain metastasis is also more likely to detect micrometastasis and result in staging and treatment changes. Its main uses are in breast cancer and malignant melanoma surgery, although it has been used in other tumor types (colon cancer) with a degree of success.[9] Other cancers which have been investigated with this technique are penile cancer, urinary bladder cancer,[10][11] prostate cancer,[12][13][14] testicular cancer[15][16] and renal cell cancer.[17][18]

Research advantages

[edit]As a bridge to translational medicine, various aspects of cancer dissemination can be studied using sentinel node detection and ensuing sentinel node biopsy. Tumor biology pertaining to metastatic capacity,[19] mechanisms of dissemination, the EMT-MET-process (epithelial–mesenchymal transition) and cancer immunology[20] are some subjects which can be more distinctly investigated.

Disadvantages

[edit]However, the technique is not without drawbacks, particularly when used for melanoma patients. This technique only has therapeutic value in patients with positive nodes.[21] Failure to detect cancer cells in the sentinel node can lead to a false negative result—there may still be cancerous cells in the lymph node basin. In addition, there is no compelling evidence that patients who have a full lymph node dissection as a result of a positive sentinel lymph node result have improved survival compared to those who do not have a full dissection until later in their disease, when the lymph nodes can be felt by a physician. Such patients may be having an unnecessary full dissection, with the attendant risk of lymphedema.[22]

History

[edit]The concept of a sentinel node was first described by Gould et al. 1960 in a patient with cancer of the parotid gland[23] and was implemented clinically on a broad scale by Cabanas in penile cancer.[24] The technique of sentinel node radiolocalization was co-founded by James C. Alex, MD, FACS and David N. Krag MD (University of Vermont Medical Center) and they were the first ones to pioneer this method for the use of cutaneous melanoma, breast cancer, head and neck cancer and Merkel cell carcinoma. Confirmative trials followed soon after.[25] Studies were also conducted at the Moffitt Cancer Center with Charles Cox, MD, Cristina Wofter, MD, Douglas Reintgen, MD and James Norman, MD. Following validation of the sentinel node biopsy technique, a number of randomised controlled trials were initiated to establish whether the technique could safely be used to avoid unnecessary axillary dissection among women with early breast cancer. The first such trial, led by Umberto Veronesi at the European Institute of Oncology, showed that women with breast tumours of 2 cm or less could safely forgo axillary dissection if their sentinel lymph nodes were found to be cancer-free on biopsy.[26] The benefits included less pain, greater arm mobility and less swelling in the arm.[27]

See also

[edit]- ALMANAC, Axillary Lymphatic Mapping Against Nodal Axillary Clearance trial

References

[edit]- ^ Storino A, Drews RE, Tawa NE (June 2021). "Malignant Cutaneous Adnexal Tumors and Role of SLNB". Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 232 (6): 889–898. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2021.01.019. PMID 33727135. S2CID 242176779.

- ^ Wang XJ, Fang F, Li YF (January 2015). "Sentinel-lymph-node procedures in early stage cervical cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Medical Oncology. 32 (1): 385. doi:10.1007/s12032-014-0385-x. PMC 4246132. PMID 25429838.

- ^ Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Aster JC, eds. (2009). Robbins & Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease (8th ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 270. ISBN 978-1-4377-2015-0.

- ^ Sherif A, Garske U, de la Torre M, Thörn M (July 2006). "Hybrid SPECT-CT: an additional technique for sentinel node detection of patients with invasive bladder cancer". European Urology. 50 (1): 83–91. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2006.03.002. PMID 16632191.

- ^ Leijte JA, Valdés Olmos RA, Nieweg OE, Horenblas S (October 2008). "Anatomical mapping of lymphatic drainage in penile carcinoma with SPECT-CT: implications for the extent of inguinal lymph node dissection". European Urology. 54 (4): 885–90. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2008.04.094. PMID 18502024.

- ^ Karakatsanis A, Christiansen PM, Fischer L, Hedin C, Pistioli L, Sund M, Rasmussen NR, Jørnsgård H, Tegnelius D, Eriksson S, Daskalakis K, Wärnberg F, Markopoulos CJ, Bergkvist L (June 2016). "The Nordic SentiMag trial: a comparison of super paramagnetic iron oxide (SPIO) nanoparticles versus Tc(99) and patent blue in the detection of sentinel node (SN) in patients with breast cancer and a meta-analysis of earlier studies". Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 157 (2): 281–294. doi:10.1007/s10549-016-3809-9. PMC 4875068. PMID 27117158.

- ^ "Sentimag". Endomag. Retrieved 2019-03-09.

- ^ BNMS (August 2011). "Lymphoscintigraphy Clinical Guidelines" (PDF). Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- ^ Tanis PJ, Boom RP, Koops HS, Faneyte IF, Peterse JL, Nieweg OE, Rutgers EJ, Tiebosch AT, Kroon BB (April 2001). "Frozen section investigation of the sentinel node in malignant melanoma and breast cancer". Annals of Surgical Oncology. 8 (3): 222–6. doi:10.1245/aso.2001.8.3.222. PMID 11314938.

- ^ Sherif A, De La Torre M, Malmström PU, Thörn M (September 2001). "Lymphatic mapping and detection of sentinel nodes in patients with bladder cancer". The Journal of Urology. 166 (3): 812–5. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(05)65842-9. PMID 11490224.

- ^ Liedberg F, Chebil G, Davidsson T, Gudjonsson S, Månsson W (January 2006). "Intraoperative sentinel node detection improves nodal staging in invasive bladder cancer". The Journal of Urology. 175 (1): 84–8, discussion 88–9. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00066-2. PMID 16406877. S2CID 32329157.

- ^ Wawroschek F, Vogt H, Weckermann D, Wagner T, Harzmann R (December 1999). "The sentinel lymph node concept in prostate cancer - first results of gamma probe-guided sentinel lymph node identification". European Urology. 36 (6): 595–600. doi:10.1159/000020054. PMID 10559614. S2CID 46760854.

- ^ Ganswindt U, Paulsen F, Corvin S, Eichhorn K, Glocker S, Hundt I, Birkner M, Alber M, Anastasiadis A, Stenzl A, Bares R, Budach W, Bamberg M, Belka C (July 2005). "Intensity modulated radiotherapy for high risk prostate cancer based on sentinel node SPECT imaging for target volume definition". BMC Cancer. 5: 91. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-5-91. PMC 1190164. PMID 16048656.

- ^ Jeschke S, Nambirajan T, Leeb K, Ziegerhofer J, Sega W, Janetschek G (June 2005). "Detection of early lymph node metastases in prostate cancer by laparoscopic radioisotope guided sentinel lymph node dissection". The Journal of Urology. 173 (6): 1943–6. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000158159.16314.eb. PMID 15879787.

- ^ Ohyama C, Chiba Y, Yamazaki T, Endoh M, Hoshi S, Arai Y (October 2002). "Lymphatic mapping and gamma probe guided laparoscopic biopsy of sentinel lymph node in patients with clinical stage I testicular tumor". The Journal of Urology. 168 (4 Pt 1): 1390–5. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64456-4. PMID 12352400.

- ^ Brouwer OR, Valdés Olmos RA, Vermeeren L, Hoefnagel CA, Nieweg OE, Horenblas S (April 2011). "SPECT/CT and a portable gamma-camera for image-guided laparoscopic sentinel node biopsy in testicular cancer". Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 52 (4): 551–4. doi:10.2967/jnumed.110.086660. PMID 21421720.

- ^ Bex A, Vermeeren L, de Windt G, Prevoo W, Horenblas S, Olmos RA (June 2010). "Feasibility of sentinel node detection in renal cell carcinoma: a pilot study". European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 37 (6): 1117–23. doi:10.1007/s00259-009-1359-7. PMID 20111964. S2CID 61891.

- ^ Sherif AM, Eriksson E, Thörn M, Vasko J, Riklund K, Ohberg L, Ljungberg BJ (April 2012). "Sentinel node detection in renal cell carcinoma. A feasibility study for detection of tumour-draining lymph nodes". BJU International. 109 (8): 1134–9. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10444.x. PMID 21883833.

- ^ Malmström PU, Ren ZP, Sherif A, de la Torre M, Wester K, Thörn M (November 2002). "Early metastatic progression of bladder carcinoma: molecular profile of primary tumor and sentinel lymph node". The Journal of Urology. 168 (5): 2240–4. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64363-7. PMID 12394767.

- ^ Marits P, Karlsson M, Sherif A, Garske U, Thörn M, Winqvist O (January 2006). "Detection of immune responses against urinary bladder cancer in sentinel lymph nodes". European Urology. 49 (1): 59–70. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2005.09.010. PMID 16321468.

- ^ Wagman LD. "Principles of Surgical Oncology" in Pazdur R, Wagman LD, Camphausen KA, Hoskins WJ (Eds) Cancer Management: A Multidisciplinary Approach Archived 2013-10-04 at the Wayback Machine. 11 ed. 2008.

- ^ Thomas JM (January 2008). "Prognostic false-positivity of the sentinel node in melanoma". Nature Clinical Practice. Oncology. 5 (1): 18–23. doi:10.1038/ncponc1014. PMID 18097453. S2CID 7068382.

- ^ Gould EA, Winship T, Philbin PH, Kerr HH (1960). "Observations on a "sentinel node" in cancer of the parotid". Cancer. 13: 77–8. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(196001/02)13:1<77::aid-cncr2820130114>3.0.co;2-d. PMID 13828575.

- ^ Cabanas RM (February 1977). "An approach for the treatment of penile carcinoma". Cancer. 39 (2): 456–66. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(197702)39:2<456::aid-cncr2820390214>3.0.co;2-i. PMID 837331.

- ^ Tanis PJ, Nieweg OE, Valdés Olmos RA, Th Rutgers EJ, Kroon BB (2001). "History of sentinel node and validation of the technique". Breast Cancer Research. 3 (2): 109–12. doi:10.1186/bcr281. PMC 139441. PMID 11250756.

- ^ Veronesi, Umberto et al. (2006) Sentinel-lymph-node biopsy as a staging procedure in breast cancer: update of a randomised controlled study. Lancet Oncol 7:983‒990 doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70947-0

- ^ Veronesi, Umberto et al. (2003) A Randomized Comparison of Sentinel-Node Biopsy with Routine Axillary Dissection in Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med 349:546-553 DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa012782

Further reading

[edit]- Alex JC, Krag DN (1993). "Gamma-probe guided localization of lymph nodes". Surgical Oncology. 2 (3): 137–43. doi:10.1016/0960-7404(93)90001-F. PMID 8252203.

- Alex JC, Weaver DL, Fairbank JT, Rankin BS, Krag DN (October 1993). "Gamma-probe-guided lymph node localization in malignant melanoma". Surgical Oncology. 2 (5): 303–8. doi:10.1016/S0960-7404(06)80006-X. PMID 8305972.

- Krag DN, Weaver DL, Alex JC, Fairbank JT (December 1993). "Surgical resection and radiolocalization of the sentinel lymph node in breast cancer using a gamma probe". Surgical Oncology. 2 (6): 335–9, discussion 340. doi:10.1016/0960-7404(93)90064-6. PMID 8130940.

- Krag DN, Meijer SJ, Weaver DL, Loggie BW, Harlow SP, Tanabe KK, Laughlin EH, Alex JC (June 1995). "Minimal-access surgery for staging of malignant melanoma". Archives of Surgery. 130 (6): 654–8, discussion 659–60. doi:10.1001/archsurg.1995.01430060092018. PMID 7539252.

- Alex JC, Krag DN (January 1996). "The gamma-probe-guided resection of radiolabeled primary lymph nodes". Surgical Oncology Clinics of North America. 5 (1): 33–41. doi:10.1016/S1055-3207(18)30403-4. PMID 8789492.

- Alex JC, Krag DN, Harlow SP, Meijer S, Loggie BW, Kuhn J, Gadd M, Weaver DL (February 1998). "Localization of regional lymph nodes in melanomas of the head and neck". Archives of Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery. 124 (2): 135–40. doi:10.1001/archotol.124.2.135. PMID 9485103.

- Alex JC (January 2004). "The application of sentinel node radiolocalization to solid tumors of the head and neck: a 10-year experience". The Laryngoscope. 114 (1): 2–19. doi:10.1097/00005537-200401000-00002. PMID 14709988. S2CID 32533879.

External links

[edit]- "Sentinel node biopsy using radiocolloid blue dye". You Tube. 22 September 2008.

- "Sentinel node biopsy". Cancer Management Handbook. August 11, 2011.

- "Sentinel Lymph Node". Know Your Body.

- "International Sentinel Node Society (ISNS)".

Sentinel lymph node

View on GrokipediaAnatomy and Physiology

Location and Structure

The sentinel lymph node (SLN) is defined as the first lymph node or group of nodes that receives lymphatic drainage directly from a primary tumor site, making it the initial site for potential metastatic spread.[6][7] This concept relies on the orderly progression of lymphatic flow, where the SLN acts as a primary filter before drainage proceeds to secondary nodes. The location of the SLN varies depending on the primary tumor's anatomical site and type. In breast cancer, the SLN is typically located in the axillary region, specifically within level I or II axillary lymph nodes in the fat pad, lateral to the pectoralis minor muscle and inferior to the axillary vein.[6] For melanomas on the lower extremities, the SLN is often in the inguinal lymph node basin, while trunk melanomas may drain to variable sites such as axillary, inguinal, or cervical nodes.[7] In breast cancer cases, while most drainage (75-90%) is to axillary SLNs, 10-25% may involve internal mammary or other nodes.[8] The SLN is one or more among the 20 to 40 total axillary lymph nodes, with 1 to 3 commonly identified as sentinels.[9][6] Histologically, the SLN shares the general structure of other lymph nodes, appearing kidney-shaped and ranging from 1 to 2 cm in size, encased in a fibrous capsule with internal trabeculae.[10] Lymph enters via multiple afferent lymphatic vessels into the subcapsular sinus, where filtration occurs through the cortex—comprising an outer B-cell follicle region and an inner T-cell paracortex—and then proceeds to the medulla with its cords of plasma cells, macrophages, and sinuses before exiting through one or two efferent vessels.[10] As the initial drainage point, SLNs are often larger than non-sentinel nodes and feature high endothelial venules (HEVs) in the paracortex, which facilitate lymphocyte entry and contribute to heightened immune cell concentrations due to early antigen exposure.[10]Role in Lymphatic Drainage

The sentinel lymph node (SLN) serves as the primary gateway in the lymphatic system, receiving lymph fluid directly from surrounding tissues and filtering out antigens, pathogens, and cellular debris before it progresses to secondary nodes. In normal physiology, lymph nodes, including the SLN, act as filters where macrophages and other immune cells engulf and process foreign particles, initiating adaptive immune responses. Dendritic cells capture antigens in peripheral tissues, migrate via afferent lymphatics to the SLN, and present these antigens via major histocompatibility complex molecules to naïve T-cells in the node's paracortex, thereby activating cytotoxic and helper T-cell responses that coordinate systemic immunity.[11][12] In pathological conditions, particularly cancer, the SLN's position in the drainage pathway makes it the initial site for detecting micrometastases, as tumor cells follow the established centripetal flow of lymphatics from the primary lesion to the SLN before disseminating to more distant nodes. This predictable drainage pattern underscores the SLN's role in early metastasis, with tumor cells entering the node through afferent lymphatics and potentially evading or suppressing local immune surveillance if antigen presentation is impaired. For instance, in breast cancer, approximately 75-90% of lymphatic drainage converges on axillary SLNs, highlighting their critical interceptive function.[13][14][8] This targeted approach leverages the SLN's immune surveillance capabilities, where effective antigen presentation can mount antitumor responses, potentially halting metastatic progression at its earliest nodal stage.[15][16][17]Detection and Biopsy Procedures

Preoperative Imaging and Mapping

Preoperative imaging and mapping of sentinel lymph nodes (SLNs) involve non-invasive or minimally invasive techniques to visualize lymphatic drainage pathways and identify SLN locations prior to surgery, facilitating precise biopsy planning and reducing operative time. These methods leverage radiotracers, dyes, or fluorescent agents injected near the tumor site to trace the first draining nodes, which reflect the lymphatic physiology of regional metastasis spread. Lymphoscintigraphy remains the cornerstone preoperative technique for SLN mapping, particularly in breast cancer and melanoma. It entails the subdermal or peritumoral injection of technetium-99m (^{99m}Tc)-labeled colloids, such as sulfur colloid in the United States or nanocolloids like human serum albumin in Europe, at a dosage of approximately 15-20 MBq as per UK guidelines. The injection, typically administered 2-24 hours before surgery in a volume of 0.2-1 mL, is followed by massage of the site to promote lymphatic uptake.[18][19] Dynamic imaging with a gamma camera, using low-energy high-resolution collimators and acquiring 400,000-500,000 counts over 5-15 minutes in anterior oblique, lateral, and optional anterior views, delineates the "hot spots" indicating SLN drainage basins. This approach achieves identification success rates exceeding 95% in breast cancer patients, allowing surgeons to mark multiple drainage sites if multifocal or aberrant patterns are observed, such as internal mammary or supraclavicular nodes.[18][20] Visual mapping agents like patent blue dye or isosulfan blue can complement lymphoscintigraphy in preoperative planning, though they are more commonly employed intraoperatively. These dyes, injected peritumorally or subareolarly in 2-5 mL volumes 15-30 minutes preoperatively in select protocols, provide blue coloration to lymphatic vessels upon incision, aiding in the confirmation of drainage patterns identified by scintigraphy.[21][22] Emerging techniques, such as indocyanine green (ICG) fluorescence imaging, have gained adoption since the early 2010s for enhanced preoperative SLN localization, particularly in cases with challenging anatomy. ICG, a near-infrared fluorescent dye, is injected subdermally or peritumorally (typically 0.5-2.5 mg in 1-2 mL) 1-24 hours prior to imaging, followed by visualization using near-infrared cameras or systems like the SPY Elite or PDE-Neo to detect fluorescent signals in real-time or via preoperative scans. This method improves detection in multifocal drainage scenarios and has shown concordance rates over 90% with traditional lymphoscintigraphy, offering advantages in resource-limited settings due to its non-radioactive nature.[23][24]Intraoperative Identification Methods

Intraoperative identification of the sentinel lymph node (SLN) relies on surgical techniques that leverage injected tracers to localize the first-draining lymph node during cancer procedures such as breast cancer or melanoma staging. These methods build on preoperative mapping by providing real-time guidance in the operating room, enabling precise excision while minimizing unnecessary lymph node removal. The primary approaches include radiocolloid detection using a gamma probe, vital blue dye visualization, the combined dual-tracer technique, and magnetic detection using superparamagnetic iron oxide (SPIO), each with standardized protocols for node confirmation and removal. The gamma probe method employs a handheld device to detect radioactivity from technetium-99m-labeled colloid (Tc-99m), injected preoperatively into the tumor site or periareolar region. During surgery, the surgeon uses the probe to scan the lymphatic basin, guiding the incision toward areas of elevated radioactivity; nodes are considered sentinel if they exhibit in vivo counts at least 10 times background levels or ex vivo counts exceeding 10% of the hottest node's count after removal. Once identified, "hot" nodes are excised, and the basin is rescanned to ensure no residual activity greater than 10% of background remains, confirming complete SLN harvest. This technique achieves SLN identification rates of approximately 90-95% when used alone, though it requires specialized equipment and radiation safety measures.[25][26][27] Blue dye visualization involves injecting a vital dye, such as isosulfan blue or patent blue V, into the tumor bed or dermis overlying the lesion, allowing direct optical tracking of lymphatic vessels that carry the dye to the SLN. The dye binds to lymphatic proteins, staining afferent vessels and the node blue within 5-15 minutes, which the surgeon visualizes under direct light without additional devices. Nodes are excised if visibly stained, often in conjunction with palpation of the axilla or groin; this method is simple and cost-effective but limited by potential obscuration in obese patients or deep basins, yielding identification rates of 80-90%. Allergic reactions to the dye occur in less than 1% of cases, though isosulfan blue has been associated with rare anaphylaxis.[28][29][26] The combined dual-tracer approach integrates Tc-99m radiocolloid with blue dye, enhancing localization by capitalizing on both radioactivity and visual cues for superior accuracy. Preoperative injection of the radiocolloid is followed by intraoperative dye administration; the surgeon first uses the gamma probe to direct dissection toward radioactive hotspots, then confirms blue-stained nodes within the same region, excising all that meet either criterion (e.g., blue staining or ex vivo counts >10% of the hottest). This gold-standard method achieves SLN identification rates of 95-98% across breast cancer and melanoma cases, reducing false negatives compared to single-tracer techniques. Post-excision, probe confirmation ensures no residual hot spots, with the dual approach particularly beneficial in challenging anatomies.[30][31][26] A non-isotopic alternative, superparamagnetic iron oxide (SPIO) nanoparticles, can be injected peritumorally up to several weeks preoperatively and detected intraoperatively using a handheld magnetometer probe to identify magnetic "hot spots" in the lymphatic basin. Nodes are considered sentinel if ex vivo signal exceeds 10 times background, similar to gamma probe criteria. This method achieves detection rates of 97-99% in breast cancer and other sites as of 2025, offering advantages in settings without nuclear medicine facilities, with low complication rates comparable to radioisotope techniques.[32][33] Recent adaptations for robotic surgery, emerging post-2020, incorporate these tracers into minimally invasive platforms, often augmented by near-infrared fluorescence imaging with indocyanine green (ICG) for enhanced visualization. In robotic-assisted SLN biopsy (e.g., for endometrial or breast cancer), the gamma probe guides initial port placement and docking, while ICG fluorescence highlights draining vessels through the robot's camera system, allowing precise dissection in confined spaces like the pelvis. Combined with carbon nanoparticles or blue dye, this yields detection rates exceeding 90%, with studies demonstrating feasibility and reduced morbidity in early adopters; however, it requires integrated imaging capabilities and surgeon training.[34][35][36]Clinical Applications

Use in Breast Cancer Staging

Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) serves as the primary method for axillary staging in patients with early-stage breast cancer, particularly those with clinically node-negative T1 or T2 tumors measuring up to 5 cm. This approach allows for the identification of the first lymph node(s) to which cancer cells are likely to spread from the primary tumor, enabling pathologists to assess for metastases without the need for complete axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) if the sentinel node is negative. By avoiding unnecessary ALND in node-negative cases, SLNB reduces risks such as lymphedema, arm morbidity, and infection while providing accurate staging information to guide adjuvant therapy decisions.[6][37] In breast cancer staging, SLN status is integral to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 8th edition guidelines, published in 2018, which classify nodal involvement based on the number and size of metastases detected in the sentinel nodes. The N category distinguishes between no regional lymph node metastases (N0), micrometastases (0.2-2.0 mm, N1mi), isolated tumor cells (≤0.2 mm, N0(i+)), and macrometastases (>2.0 mm, N1 or higher), directly influencing the overall anatomic and prognostic stage groups. Micrometastases, often occult on routine hematoxylin and eosin staining, are detected through enhanced techniques such as immunohistochemistry (IHC) for cytokeratins or reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for epithelial markers, improving sensitivity for minimal disease burden.[38][39][40] Key clinical trials have validated SLNB's reliability in breast cancer. The National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) B-32 trial, enrolling patients from 2001 to 2004 with results reported through 2010, evaluated SLNB followed by ALND in clinically node-negative women and found an overall accuracy of 97.1% and a false-negative rate of 9.8%, confirming SLNB as a safe alternative to routine ALND for accurate nodal assessment. Similarly, the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group (ACOSOG) Z0011 trial, published in 2011 with long-term follow-up in 2017, demonstrated that among women with T1-T2 tumors, clinical T1-T2N0 disease, and 1-2 positive sentinel nodes undergoing breast-conserving surgery and whole-breast radiation, omitting completion ALND resulted in equivalent 10-year overall survival (86.3% vs. 83.6%) and regional recurrence rates compared to ALND.[41][42] Recent guideline updates emphasize de-escalation strategies for low-risk breast cancer to further minimize surgical intervention. The 2021 joint guidelines from ASCO and Cancer Care Ontario recommend against routine SLNB in select low-risk patients, such as those over 70 years with hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative, T1 tumors and node-negative clinical staging on imaging, where the risk of axillary metastasis is under 10% and endocrine therapy alone suffices. These recommendations build on trial evidence to prioritize quality of life while maintaining oncologic outcomes, with ongoing studies exploring even broader omission criteria.[43][44]Use in Melanoma and Other Skin Cancers

Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) is a standard procedure for staging intermediate-thickness melanomas, defined as those with a Breslow depth of 1 to 4 mm, where the primary tumor drains to regional lymph node basins such as cervical, axillary, or inguinal depending on the lesion's anatomic location.[45] This protocol involves preoperative lymphoscintigraphy to map drainage patterns, followed by intraoperative identification using blue dye and/or radiocolloid, allowing for targeted removal of the first node(s) receiving lymphatic flow from the tumor site.[46] The procedure is recommended for clinically node-negative patients to detect occult micrometastases, which occur in approximately 15-25% of such cases and inform subsequent management.[47] According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines (Version 2.2025), SLNB plays a pivotal role in melanoma staging and influences decisions on adjuvant therapy, particularly for patients with positive sentinel nodes who may benefit from immunotherapy or targeted agents to reduce recurrence risk.[48] A positive SLNB result upstages the disease to N1 or higher, prompting consideration of systemic treatments like anti-PD-1 inhibitors, whereas a negative result supports observation or less intensive follow-up. The Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial I (MSLT-I), published in 2014, demonstrated that while overall melanoma-specific survival was similar between SLNB followed by completion lymphadenectomy and nodal observation (81.4% vs. 78.3% at 10 years), patients with node-positive disease experienced improved distant disease-free survival with early SLNB-based intervention (50.5% vs. 40.7%).[49] The trial also reported a false-negative rate of 5.0%, highlighting SLNB's high accuracy in identifying nodal involvement.[49] Beyond melanoma, SLNB has been extended to other aggressive skin cancers, including Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC), where post-2020 evidence supports its use for prognostic staging and guiding adjuvant radiation or immunotherapy in clinically node-negative patients.[50] In MCC, SLNB detects occult metastases in up to 20-30% of cases, correlating with reduced regional recurrence and improved overall survival when combined with multimodal therapy.[51] Similarly, for high-risk cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC), emerging post-2020 data indicate that SLNB improves prognostic accuracy in tumors with features like perineural invasion or immunosuppression, identifying nodal spread in 5-15% of patients and facilitating earlier intervention to enhance outcomes.[52] These applications underscore SLNB's value in non-melanoma skin malignancies with lymphatic metastatic potential, though guidelines emphasize case selection based on tumor biology and patient factors.[53]Applications in Gynecological and Head/Neck Cancers

In gynecological cancers, sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy has become a key staging tool, particularly for early-stage endometrial and cervical carcinomas, where indocyanine green (ICG) fluorescence imaging enhances detection accuracy. The SENTIREC-endo study, a national prospective cohort evaluating SLN mapping in high-risk endometrial cancer, demonstrated that a protocolled approach using ICG cervical injection achieved bilateral SLN detection in over 80% of cases, allowing omission of systematic lymphadenectomy and reducing the need for para-aortic dissection in node-negative patients.[54] This technique minimizes surgical morbidity while maintaining oncologic safety, as evidenced by low false-negative rates (under 5%) in multicenter trials.[55] For vulvar cancer, SLN biopsy with ICG or technetium-99m is recommended for unifocal tumors under 4 cm, limiting inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy to SLN-positive cases and reducing lymphedema risk by up to 50%.[56] The 2023 FIGO staging system for endometrial cancer incorporates SLN biopsy as an alternative to full lymphadenectomy for apparent early-stage disease, particularly in low- to intermediate-risk histologies, improving nodal metastasis detection without increasing recurrence rates.[57] In cervical cancer, ICG-guided SLN mapping via intracervical injection yields detection rates exceeding 90%, supporting its use in FIGO stages IA2-IB2 to guide fertility-sparing approaches.[58] In head and neck cancers, SLN biopsy is applied to clinically node-negative oral cavity and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas (SCC), using peritumoral injection of technetium-99m colloid or ICG for lymphatic mapping. Detection rates range from 80% to 90% in T1-T2 tumors, with pooled sensitivity of 87% and negative predictive value of 94%, enabling selective neck dissection and avoiding elective procedures in up to 70% of node-negative cases.[59] For oropharyngeal SCC, peritumoral injection facilitates identification of level II-III nodes, though challenges arise in floor-of-mouth tumors due to crossover drainage.[60] Controversies persist in human papillomavirus (HPV)-positive oropharyngeal SCC, where favorable prognosis prompts debate on SLN utility; while it accurately stages N0 necks, some studies question its necessity given low metastasis rates (under 20%) and potential for overtreatment, advocating de-escalation trials to validate skipping dissection in SLN-negative HPV+ cases.[61][62] Emerging applications include SLN biopsy in thyroid and pancreatic cancers, though adoption remains limited. In papillary thyroid carcinoma, ICG or blue dye mapping achieves detection rates of 85-95% for central compartment nodes, with 2024-2025 meta-analyses reporting sensitivity over 90% for micrometastases, potentially reducing prophylactic neck dissections.[63] For pancreatic adenocarcinoma, preliminary 2024 data using 99mTc-phytate injection show SLN identification in 70-80% of resectable cases, aiding in tailoring adjuvant therapy, but larger trials are needed to confirm oncologic benefits.[64][65]Advantages, Limitations, and Outcomes

Clinical Benefits and Evidence

Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) offers significant clinical benefits by minimizing postoperative morbidity compared to traditional axillary lymph node dissection (ALND), particularly in reducing the incidence of lymphedema. Studies indicate that lymphedema occurs in approximately 0-13% of patients following SLNB, a substantial decrease from the 13-28% rate associated with full ALND.[66] This reduction is attributed to the targeted removal of only the sentinel nodes, preserving lymphatic drainage pathways and decreasing surgical trauma to the axillary region.[67] In addition to improved quality of life through lower complication rates, SLNB demonstrates cost-effectiveness in breast cancer management. Economic analyses have shown that SLNB can save approximately $883 per patient over 20 years compared to ALND, due to shorter hospital stays, fewer complications, and reduced need for long-term supportive care.[68] These savings are amplified when SLNB allows omission of further dissection in node-negative cases, optimizing resource allocation without compromising care.[69] Major clinical trials provide robust evidence supporting SLNB's efficacy and safety. The ACOSOG Z0011 trial, involving 891 women with early-stage breast cancer and 1-2 positive sentinel nodes undergoing breast-conserving surgery, demonstrated no significant difference in 10-year overall survival (86.3% with SLNB alone vs. 83.6% with completion ALND) or disease-free survival, validating the omission of full dissection in select patients.[42] Similarly, the SOUND trial (Sentinel Node vs. Observation After Axillary Ultra-souND), a phase 3 noninferiority study of over 1,400 patients with clinically node-negative early breast cancer, showed that omitting SLNB entirely was noninferior to performing it, with 5-year disease-free survival rates of 94.6% in the no-SLNB arm versus 95.2% in the SLNB arm, further supporting de-escalation in low-risk cases.[70] SLNB achieves high diagnostic accuracy, with overall sensitivity ranging from 90-95% in identifying nodal metastases across various cancers.[71] Recent meta-analyses confirm oncologic equivalence between SLNB and ALND in terms of survival outcomes in early breast cancer patients. These findings underscore SLNB's role in precise staging while avoiding overtreatment, applicable in breast cancer and extending to melanoma—for instance, the Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial (MSLT-I) showed no survival detriment with SLNB alone in node-negative melanoma—and gynecological malignancies. In melanoma, the MSLT-II trial (over 1,900 patients) demonstrated that active surveillance after positive SLNB is noninferior to completion dissection, reducing morbidity without affecting 5-year melanoma-specific survival (84% vs. 86%). For gynecological cancers like endometrial and vulvar, validation studies report 90-95% sensitivity, supporting SLNB as standard with reduced complications compared to full lymphadenectomy. Emerging applications in colorectal and head-and-neck cancers show similar high accuracy as of 2025.[3]Risks, Complications, and Controversies

Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) carries several procedural risks, including allergic reactions to the blue dye used for mapping, which occur in approximately 1-2% of cases and can range from mild skin reactions to severe anaphylaxis.[72] Infections and hematomas at the biopsy site are also reported, affecting less than 5% of patients, with axillary wound infections in about 1% and hematomas in 1.4%.[73] These risks are generally low but necessitate careful patient monitoring during and after the procedure. A key limitation of SLNB is the potential for false-negative results, where metastatic disease is missed, occurring in 5-15% of cases primarily due to skipped sentinel nodes or incomplete mapping.[74] This rate can vary by cancer type and surgeon experience, with studies reporting figures as high as 14.4% in breast cancer despite quality controls.[75] False negatives may lead to understaging and delayed treatment, underscoring the importance of validation in high-risk scenarios. Post-biopsy complications include seroma formation, affecting up to 7.1% of patients, and shoulder dysfunction from nerve irritation or limited mobility.[73] Lymphedema risk is reduced compared to full axillary dissection but still present in a subset of cases, particularly with multiple node removals.[15] Surgeon proficiency plays a critical role, with a learning curve requiring 20-30 cases to achieve reliable identification rates above 90%.[76] Early procedures during this phase may increase false-negative risks, emphasizing the need for supervised training.[77] Indocyanine green (ICG) fluorescence offers a safer alternative to blue dye for mapping, with lower rates of allergic reactions as noted in a 2023 review of its use in breast cancer SLNB.[78] No severe adverse events were reported in multiple studies validating ICG's safety profile.[79] Ongoing controversies surround the necessity of SLNB versus completion lymph node dissection, particularly in low-risk early-stage breast cancer, where 2025 ASCO guidelines endorse omission in postmenopausal women aged 50 or older with hormone receptor-positive tumors to avoid unnecessary morbidity.[80] Debate persists on balancing staging accuracy against overtreatment, with trials like INSEMA supporting non-inferior survival outcomes without biopsy in select cases.[43] Equity concerns arise in SLNB access, with racial disparities showing lower utilization rates among Black patients (62.4%) compared to White patients (73.7%) in breast cancer, potentially exacerbating outcomes in non-breast applications like melanoma.[81] These gaps highlight barriers in informed decision-making and resource availability across cancer types.[82]Historical Development

Early Discoveries and Concepts

The concept of the sentinel lymph node arose as a refinement to the prevailing surgical paradigms of the mid-20th century, which were dominated by the Halstedian approach of radical en bloc resection of tumors and entire regional lymphatic basins to prevent metastatic spread. This method, introduced by William S. Halsted in the late 19th century for breast cancer and extended to other malignancies, assumed sequential, orderly progression of cancer through lymphatics but often resulted in substantial morbidity from unnecessary lymph node removal. The emerging sentinel node idea posited that the first lymph node (or nodes) receiving drainage from a primary tumor—the sentinel—could serve as a indicator for the status of the broader lymphatic basin, enabling selective targeting and biopsy to guide whether full dissection was warranted.[2] Pioneering experiments with vital dyes in the 1950s provided initial evidence for intraoperative lymphatic visualization. In 1950, surgeons J.A. Weinberg and E.M. Greaney reported using a vital staining dye during gastric cancer operations to identify and isolate regional lymph nodes, demonstrating that dyes could trace drainage pathways and highlight key nodes for assessment.[83] This technique built on earlier anatomical insights into lymphatic physiology, where lymph nodes function as primary filters for interstitial fluid and potential pathogens or tumor cells from upstream tissues. A decade later, in 1960, Ernest A. Gould and colleagues advanced the concept by coining the term "sentinel node" based on intraoperative observations during parotidectomies for parotid tumors; they identified a consistent, seemingly normal-appearing node at the junction of the facial and retromandibular veins that, if involved, signaled metastases in the neck, advocating its examination to avoid routine radical neck dissection.[84] Pre-1970s animal studies further elucidated lymphatic mapping principles, confirming the sentinel node's role in sequential drainage. In 1940, R.K. Gilchrist injected carbon particles into the mesenteries of dogs and rabbits, observing that particles were trapped in the first encountered lymph nodes, illustrating their barrier function and the potential for focal spread patterns.[2] Similarly, in 1954, I. Zeidman and J.M. Buss conducted experiments in rabbits by injecting V2 carcinoma cells into peripheral lymph nodes, finding that tumor cells were predominantly retained in the initial node for weeks, supporting the hypothesis of a primary "sentinel" site for metastasis detection.[85] Early recognition of predictable drainage patterns also emerged in penile cancer, where anatomical studies highlighted the sentinel node's utility in staging. By the 1960s, investigations into penile neoplasms revealed that lymphatic fluid followed a constrained pathway through specific inguinal nodes, prompting targeted approaches over extensive dissections; this laid groundwork for later lymphangiographic mapping that identified primary draining nodes medial to the superficial epigastric vein.[86]Key Milestones and Modern Trials

The concept of sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) gained clinical traction in 1977 when urologist Ramon M. Cabanas introduced it for penile carcinoma, demonstrating through lymphangiography in 100 patients that a specific "sentinel" node in the iliac region served as the primary drainage site, allowing targeted biopsy to assess metastasis without full lymphadenectomy. In the 1990s, surgical oncologist Donald L. Morton advanced SLNB for melanoma through intraoperative lymphatic mapping using blue dye, with early trials at the John Wayne Cancer Institute establishing its feasibility for identifying the first-draining node in early-stage disease, leading to the Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial-I (MSLT-I) initiated in 1994 to evaluate staging accuracy. Concurrently, David N. Krag pioneered the use of a gamma probe for radiolocalization in breast cancer, reporting in 1993 the successful identification of sentinel nodes in 18 of 22 patients via technetium-99m injection, enabling precise intraoperative detection and marking a shift toward minimally invasive axillary staging.[88] This built on the first human SLNB for breast cancer performed in 1994 by Armando E. Giuliano, who adapted vital dye mapping to excise the sentinel node in clinical T1 tumors, confirming its accuracy in reflecting axillary status.[89] Modern trials solidified SLNB's role in reducing morbidity without compromising survival. Umberto Veronesi's 2006 single-center randomized controlled study, updating a prior trial to include 516 patients with tumors ≤2 cm, found that SLNB alone versus SLNB plus axillary dissection showed equivalent 5-year disease-free survival rates (no detriment observed) and lower arm morbidity in the SLNB group.[90] For melanoma, the MSLT-II trial, with results influencing practice by 2020, randomized 1,934 patients with sentinel-positive nodes to completion lymphadenectomy versus nodal observation, demonstrating in 3-year follow-up (updated analyses through 2020) that immediate dissection improved regional control but did not enhance melanoma-specific survival or distant metastasis-free survival, thus favoring observation with ultrasound monitoring to time interventions based on recurrence risk. Post-2020 advancements continue to explore artificial intelligence (AI) for enhanced mapping precision in SLNB procedures.References

- https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(197704)39:2<456::AID-CNCR2820390214>3.0.CO;2-I