Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Smith chart

View on WikipediaThe Smith chart (sometimes also called Smith diagram, Mizuhashi chart (水橋チャート), Mizuhashi–Smith chart (水橋スミスチャート),[1][2][3] Volpert–Smith chart (Диаграмма Вольперта—Смита)[4][5] or Mizuhashi–Volpert–Smith chart) is a graphical calculator or nomogram designed for electrical and electronics engineers specializing in radio frequency (RF) engineering to assist in solving problems with transmission lines and matching circuits.[6][7][8][9][10]

It was independently[11][4][12][5] proposed by Tōsaku Mizuhashi (水橋東作) in 1937,[13] and by Amiel R. Volpert (Амиэ́ль Р. Во́льперт)[14][4] and Phillip H. Smith in 1939.[15][16] Starting with a rectangular diagram, Smith had developed a special polar coordinate chart by 1936, which, with the input of his colleagues Enoch B. Ferrell and James W. McRae, who were familiar with conformal mappings, was reworked into the final form in early 1937, which was eventually published in January 1939.[15][9][17] While Smith had originally called it a "transmission line chart"[15][16] and other authors first used names like "reflection chart", "circle diagram of impedance", "immittance chart" or "Z-plane chart",[9] early adopters at MIT's Radiation Laboratory started to refer to it simply as "Smith chart" in the 1940s,[9][17] a name generally accepted in the Western world by 1950.[18][19]

The Smith chart can be used to simultaneously display multiple parameters including impedances, admittances, reflection coefficients, scattering parameters, noise figure circles, constant gain contours and regions for unconditional stability.[20][21]: 93–103 The Smith chart is most frequently used at or within the unity radius region. However, the remainder is still mathematically relevant, being used, for example, in oscillator design and stability analysis.[21]: 98–101 While the use of paper Smith charts for solving the complex mathematics involved in matching problems has been largely replaced by software based methods, the Smith chart is still a very useful method of showing[22] how RF parameters behave at one or more frequencies, an alternative to using tabular information. Thus most RF circuit analysis software includes a Smith chart option for the display of results and all but the simplest impedance measuring instruments can plot measured results on a Smith chart display.[23]

Overview

[edit]

The Smith chart is a mathematical transformation of the two-dimensional Cartesian complex plane. Complex numbers with positive real parts map inside the circle. Those with negative real parts map outside the circle. If we are dealing only with impedances with non-negative resistive components, our interest is focused on the area inside the circle. The transformation, for an impedance Smith chart, is:

where z = Z/Z0, i.e., the complex impedance, Z, normalized by the reference impedance, Z0. The impedance Smith chart is then an Argand plot of impedances thus transformed. Impedances with non-negative resistive components will appear inside a circle with unit radius; the origin will correspond to the reference impedance, Z0.

The Smith chart is plotted on the complex reflection coefficient plane in two dimensions and may be scaled in normalised impedance (the most common), normalised admittance or both, using different colours to distinguish between them. These are often known as the Z, Y and YZ Smith charts respectively.[21]: 97 Normalised scaling allows the Smith chart to be used for problems involving any characteristic or system impedance which is represented by the center point of the chart. The most commonly used normalization impedance is 50 ohms. Once an answer is obtained through the graphical constructions described below, it is straightforward to convert between normalised impedance (or normalised admittance) and the corresponding unnormalized value by multiplying by the characteristic impedance (admittance). Reflection coefficients can be read directly from the chart as they are unitless parameters.

The Smith chart has a scale around its circumference or periphery which is graduated in wavelengths and degrees. The wavelengths scale is used in distributed component problems and represents the distance measured along the transmission line connected between the generator or source and the load to the point under consideration. The degrees scale represents the angle of the voltage reflection coefficient at that point. The Smith chart may also be used for lumped-element matching and analysis problems.

Use of the Smith chart and the interpretation of the results obtained using it requires a good understanding of AC circuit theory and transmission-line theory, both of which are prerequisites for RF engineers.

As impedances and admittances change with frequency, problems using the Smith chart can only be solved manually using one frequency at a time, the result being represented by a point. This is often adequate for narrow band applications (typically up to about 5% to 10% bandwidth) but for wider bandwidths it is usually necessary to apply Smith chart techniques at more than one frequency across the operating frequency band. Provided the frequencies are sufficiently close, the resulting Smith chart points may be joined by straight lines to create a locus.

A locus of points on a Smith chart covering a range of frequencies can be used to visually represent:

- how capacitive or how inductive a load is across the frequency range

- how difficult matching is likely to be at various frequencies

- how well matched a particular component is.

The accuracy of the Smith chart is reduced for problems involving a large locus of impedances or admittances, although the scaling can be magnified for individual areas to accommodate these.

Mathematical basis

[edit]

Actual and normalised impedance and admittance

[edit]A transmission line with a characteristic impedance of may be universally considered to have a characteristic admittance of where

Any impedance, expressed in ohms, may be normalised by dividing it by the characteristic impedance, so the normalised impedance using the lower case zT is given by

Similarly, for normalised admittance

The SI unit of impedance is the ohm with the symbol of the upper case Greek letter omega (Ω) and the SI unit for admittance is the siemens with the symbol of an upper case letter S. Normalised impedance and normalised admittance are dimensionless. Actual impedances and admittances must be normalised before using them on a Smith chart. Once the result is obtained it may be de-normalised to obtain the actual result.

The normalised impedance Smith chart

[edit]

Using transmission-line theory, if a transmission line is terminated in an impedance () which differs from its characteristic impedance (), a standing wave will be formed on the line comprising the resultant of both the incident or forward () and the reflected or reversed () waves. Using complex exponential notation:

- and

where

- is the temporal part of the wave

- is the spatial part of the wave and

- where

- is the angular frequency in radians per second (rad/s)

- is the frequency in hertz (Hz)

- is the time in seconds (s)

- and are constants

- is the distance measured along the transmission line from the load toward the generator in metres (m)

Also

- is the propagation constant which has SI units radians/meter

where

- is the attenuation constant in nepers per metre (Np/m)

- is the phase constant in radians per metre (rad/m)

The Smith chart is used with one frequency () at a time, and only for one moment () at a time, so the temporal part of the phase () is fixed. All terms are actually multiplied by this to obtain the instantaneous phase, but it is conventional and understood to omit it. Therefore,

- and

where and are respectively the forward and reverse voltage amplitudes at the load.

The variation of complex reflection coefficient with position along the line

[edit]

The complex voltage reflection coefficient is defined as the ratio of the reflected wave to the incident (or forward) wave. Therefore,

where C is also a constant.

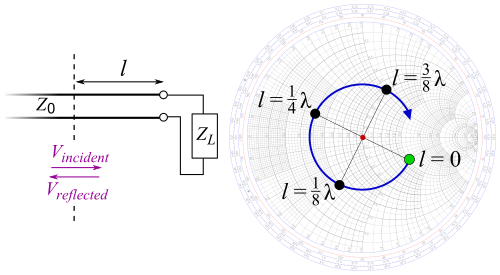

For a uniform transmission line (in which is constant), the complex reflection coefficient of a standing wave varies according to the position on the line. If the line is lossy ( is non-zero) this is represented on the Smith chart by a spiral path. In most Smith chart problems however, losses can be assumed negligible () and the task of solving them is greatly simplified. For the loss free case therefore, the expression for complex reflection coefficient becomes

where is the reflection coefficient at the load, and is the line length from the load to the location where the reflection coefficient is measured. The phase constant may also be written as

where is the wavelength within the transmission line at the test frequency.

Therefore,

This equation shows that, for a standing wave, the complex reflection coefficient and impedance repeats every half wavelength along the transmission line. The complex reflection coefficient is generally simply referred to as reflection coefficient. The outer circumferential scale of the Smith chart represents the distance from the generator to the load scaled in wavelengths and is therefore scaled from zero to 0.50.

The variation of normalised impedance with position along the line

[edit]If and are the voltage across and the current entering the termination at the end of the transmission line respectively, then

and

- .

By dividing these equations and substituting for both the voltage reflection coefficient

and the normalised impedance of the termination represented by the lower case z, subscript T

gives the result:

Alternatively, in terms of the reflection coefficient

These are the equations which are used to construct the Z Smith chart. Mathematically speaking and are related via a Möbius transformation.

Both and are expressed in complex numbers without any units. They both change with frequency so for any particular measurement, the frequency at which it was performed must be stated together with the characteristic impedance.

may be expressed in magnitude and angle on a polar diagram. Any actual reflection coefficient must have a magnitude of less than or equal to unity so, at the test frequency, this may be expressed by a point inside a circle of unity radius. The Smith chart is actually constructed on such a polar diagram. The Smith chart scaling is designed in such a way that reflection coefficient can be converted to normalised impedance or vice versa. Using the Smith chart, the normalised impedance may be obtained with appreciable accuracy by plotting the point representing the reflection coefficient treating the Smith chart as a polar diagram and then reading its value directly using the characteristic Smith chart scaling. This technique is a graphical alternative to substituting the values in the equations.

By substituting the expression for how reflection coefficient changes along an unmatched loss-free transmission line

for the loss free case, into the equation for normalised impedance in terms of reflection coefficient

and using Euler's formula

yields the impedance-version transmission-line equation for the loss free case:[24]

where is the impedance 'seen' at the input of a loss free transmission line of length terminated with an impedance

Versions of the transmission-line equation may be similarly derived for the admittance loss free case and for the impedance and admittance lossy cases.

The Smith chart graphical equivalent of using the transmission-line equation is to normalise to plot the resulting point on a Z Smith chart and to draw a circle through that point centred at the Smith chart centre. The path along the arc of the circle represents how the impedance changes whilst moving along the transmission line. In this case the circumferential (wavelength) scaling must be used, remembering that this is the wavelength within the transmission line and may differ from the free space wavelength.

Regions of the Z Smith chart

[edit]If a polar diagram is mapped on to a cartesian coordinate system it is conventional to measure angles relative to the positive x-axis using a counterclockwise direction for positive angles. The magnitude of a complex number is the length of a straight line drawn from the origin to the point representing it. The Smith chart uses the same convention, noting that, in the normalised impedance plane, the positive x-axis extends from the center of the Smith chart at to the point The region above the x-axis represents inductive impedances (positive imaginary parts) and the region below the x-axis represents capacitive impedances (negative imaginary parts).

If the termination is perfectly matched, the reflection coefficient will be zero, represented effectively by a circle of zero radius or in fact a point at the centre of the Smith chart. If the termination was a perfect open circuit or short circuit the magnitude of the reflection coefficient would be unity, all power would be reflected and the point would lie at some point on the unity circumference circle.

Circles of constant normalised resistance and constant normalised reactance

[edit]The normalised impedance Smith chart is composed of two families of circles: circles of constant normalised resistance and circles of constant normalised reactance. In the complex reflection coefficient plane the Smith chart occupies a circle of unity radius centred at the origin. In cartesian coordinates therefore the circle would pass through the points (+1,0) and (−1,0) on the x-axis and the points (0,+1) and (0,−1) on the y-axis.

Since both and are complex numbers, in general they may be written as:

with a, b, c and d real numbers.

Substituting these into the equation relating normalised impedance and complex reflection coefficient:

gives the following result:

This is the equation which describes how the complex reflection coefficient changes with the normalised impedance and may be used to construct both families of circles.[25]

The Y Smith chart

[edit]The Y Smith chart is constructed in a similar way to the Z Smith chart case but by expressing values of voltage reflection coefficient in terms of normalised admittance instead of normalised impedance. The normalised admittance yT is the reciprocal of the normalised impedance zT, so

Therefore:

and

The Y Smith chart appears like the normalised impedance, type but with the graphic nested circles rotated through 180°, but the numeric scale remaining in its same position (not rotated) as the Z chart.

Similarly taking

for real and gives an analogous result, although with more and different minus signs:

The region above the x-axis represents capacitive admittances and the region below the x-axis represents inductive admittances. Capacitive admittances have positive imaginary parts and inductive admittances have negative imaginary parts.

Again, if the termination is perfectly matched the reflection coefficient will be zero, represented by a 'circle' of zero radius or in fact a point at the centre of the Smith chart. If the termination was a perfect open or short circuit the magnitude of the voltage reflection coefficient would be unity, all power would be reflected and the point would lie at some point on the unity circumference circle of the Smith chart.

Practical examples

[edit]

A point with a reflection coefficient magnitude 0.63 and angle 60° represented in polar form as , is shown as point P1 on the Smith chart. To plot this, one may use the circumferential (reflection coefficient) angle scale to find the graduation and a ruler to draw a line passing through this and the centre of the Smith chart. The length of the line would then be scaled to P1 assuming the Smith chart radius to be unity. For example, if the actual radius measured from the paper was 100 mm, the length OP1 would be 63 mm.

The following table gives some similar examples of points which are plotted on the Z Smith chart. For each, the reflection coefficient is given in polar form together with the corresponding normalised impedance in rectangular form. The conversion may be read directly from the Smith chart or by substitution into the equation.

| Point identity | Reflection coefficient (polar form) | Normalised impedance (rectangular form) |

|---|---|---|

| P1 (Inductive) | ||

| P2 (Inductive) | ||

| P3 (Capacitive) |

Working with both the Z Smith chart and the Y Smith charts

[edit]In RF circuit and matching problems sometimes it is more convenient to work with admittances (representing conductances and susceptances) and sometimes it is more convenient to work with impedances (representing resistances and reactances). Solving a typical matching problem will often require several changes between both types of Smith chart, using normalised impedance for series elements and normalised admittances for parallel elements. For these a dual (normalised) impedance and admittance Smith chart may be used. Alternatively, one type may be used and the scaling converted to the other when required. In order to change from normalised impedance to normalised admittance or vice versa, the point representing the value of reflection coefficient under consideration is moved through exactly 180 degrees at the same radius. For example, the point P1 in the example representing a reflection coefficient of has a normalised impedance of . To graphically change this to the equivalent normalised admittance point, say Q1, a line is drawn with a ruler from P1 through the Smith chart centre to Q1, an equal radius in the opposite direction. This is equivalent to moving the point through a circular path of exactly 180 degrees. Reading the value from the Smith chart for Q1, remembering that the scaling is now in normalised admittance, gives . Performing the calculation

manually will confirm this.

Once a transformation from impedance to admittance has been performed, the scaling changes to normalised admittance until a later transformation back to normalised impedance is performed.

The table below shows examples of normalised impedances and their equivalent normalised admittances obtained by rotation of the point through 180°. Again, these may be obtained either by calculation or using a Smith chart as shown, converting between the normalised impedance and normalised admittances planes.

| Normalised impedance | Normalised admittance |

|---|---|

| P1 () | Q1 () |

| P10 () | Q10 () |

Choice of Smith chart type and component type

[edit]The choice of whether to use the Z Smith chart or the Y Smith chart for any particular calculation depends on which is more convenient. Impedances in series and admittances in parallel add while impedances in parallel and admittances in series are related by a reciprocal equation. If is the equivalent impedance of series impedances and is the equivalent impedance of parallel impedances, then

For admittances the reverse is true, that is

Dealing with the reciprocals, especially in complex numbers, is more time-consuming and error-prone than using linear addition. In general therefore, most RF engineers work in the plane where the circuit topography supports linear addition. The following table gives the complex expressions for impedance (real and normalised) and admittance (real and normalised) for each of the three basic passive circuit elements: resistance, inductance and capacitance. Using just the characteristic impedance (or characteristic admittance) and test frequency an equivalent circuit can be found and vice versa.

| Element type | Impedance (Z or z) or Reactance (X or x) | Admittance (Y or y) or Susceptance (B or b) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actual (Ω) |

Normalised (no units) |

Actual (S) |

Normalised (no units) | |

| Resistance (R) | ||||

| Inductance (L) | ||||

| Capacitance (C) | ||||

Using the Smith chart to solve conjugate matching problems with distributed components

[edit]Distributed matching becomes feasible and is sometimes required when the physical size of the matching components is more than about 5% of a wavelength at the operating frequency. Here the electrical behaviour of many lumped components becomes rather unpredictable. This occurs in microwave circuits and when high power requires large components in shortwave, FM and TV broadcasting.

For distributed components the effects on reflection coefficient and impedance of moving along the transmission line must be allowed for using the outer circumferential scale of the Smith chart which is calibrated in wavelengths.

The following example shows how a transmission line, terminated with an arbitrary load, may be matched at one frequency either with a series or parallel reactive component in each case connected at precise positions.

Supposing a loss-free air-spaced transmission line of characteristic impedance , operating at a frequency of 800 MHz, is terminated with a circuit comprising a 17.5 resistor in series with a 6.5 nanohenry (6.5 nH) inductor. How may the line be matched?

From the table above, the reactance of the inductor forming part of the termination at 800 MHz is

so the impedance of the combination () is given by

and the normalised impedance () is

This is plotted on the Z Smith chart at point P20. The line OP20 is extended through to the wavelength scale where it intersects at the point . As the transmission line is loss free, a circle centred at the centre of the Smith chart is drawn through the point P20 to represent the path of the constant magnitude reflection coefficient due to the termination. At point P21 the circle intersects with the unity circle of constant normalised resistance at

- .

The extension of the line OP21 intersects the wavelength scale at , therefore the distance from the termination to this point on the line is given by

Since the transmission line is air-spaced, the wavelength at 800 MHz in the line is the same as that in free space and is given by

where is the velocity of electromagnetic radiation in free space and is the frequency in hertz. The result gives , making the position of the matching component 29.6 mm from the load.

The conjugate match for the impedance at P21 () is

As the Smith chart is still in the normalised impedance plane, from the table above a series capacitor is required where

Rearranging, we obtain

- .

Substitution of known values gives

To match the termination at 800 MHz, a series capacitor of 2.6 pF must be placed in series with the transmission line at a distance of 29.6 mm from the termination.

An alternative shunt match could be calculated after performing a Smith chart transformation from normalised impedance to normalised admittance. Point Q20 is the equivalent of P20 but expressed as a normalised admittance. Reading from the Smith chart scaling, remembering that this is now a normalised admittance gives

(In fact this value is not actually used). However, the extension of the line OQ20 through to the wavelength scale gives . The earliest point at which a shunt conjugate match could be introduced, moving towards the generator, would be at Q21, the same position as the previous P21, but this time representing a normalised admittance given by

- .

The distance along the transmission line is in this case

which converts to 123 mm.

The conjugate matching component is required to have a normalised admittance () of

- .

From the table it can be seen that a negative admittance would require an inductor, connected in parallel with the transmission line. If its value is , then

This gives the result

A suitable inductive shunt matching would therefore be a 6.5 nH inductor in parallel with the line positioned at 123 mm from the load.

Using the Smith chart to analyze lumped-element circuits

[edit]The analysis of lumped-element components assumes that the wavelength at the frequency of operation is much greater than the dimensions of the components themselves. The Smith chart may be used to analyze such circuits in which case the movements around the chart are generated by the (normalized) impedances and admittances of the components at the frequency of operation. In this case the wavelength scaling on the Smith chart circumference is not used. The following circuit will be analyzed using a Smith chart at an operating frequency of 100 MHz. At this frequency the free space wavelength is 3 m. The component dimensions themselves will be in the order of millimetres so the assumption of lumped components will be valid. Despite there being no transmission line as such, a system impedance must still be defined to enable normalization and de-normalization calculations and is a good choice here as . If there were very different values of resistance present a value closer to these might be a better choice.

The analysis starts with a Z Smith chart looking into R1 only with no other components present. As is the same as the system impedance, this is represented by a point at the centre of the Smith chart. The first transformation is OP1 along the line of constant normalized resistance in this case the addition of a normalized reactance of -j0.80, corresponding to a series capacitor of 40 pF. Points with suffix P are in the Z plane and points with suffix Q are in the Y plane. Therefore, transformations P1 to Q1 and P3 to Q3 are from the Z Smith chart to the Y Smith chart and transformation Q2 to P2 is from the Y Smith chart to the Z Smith chart. The following table shows the steps taken to work through the remaining components and transformations, returning eventually back to the centre of the Smith chart and a perfect 50 ohm match.

| Transformation | Plane | x or b Normalized value | Capacitance/Inductance | Formula to Solve | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capacitance (Series) | |||||

| Inductance (Shunt) | |||||

| Z | Capacitance (Series) | ||||

| Y | Capacitance (Shunt) |

3D Smith chart

[edit]

A generalization of the Smith chart to a three dimensional sphere, based on the extended complex plane (Riemann sphere) and inversive geometry, was proposed by Muller, et al in 2011.[26]

The chart unifies the passive and active circuit design on little and big circles on the surface of a unit sphere, using a stereographic conformal map of the reflection coefficient's generalized plane. Considering the point at infinity, the space of the new chart includes all possible loads: The north pole is the perfectly matched point, while the south pole is the completely mismatched point.[26]

The 3D Smith chart has been further extended outside of the spherical surface, for plotting various scalar parameters, such as group delay, quality factors, or frequency orientation. The visual frequency orientation (clockwise vs. counter-clockwise) enables one to differentiate between a negative / capacitance and positive / inductive whose reflection coefficients are the same when plotted on a 2D Smith chart, but whose orientations diverge as frequency increases.[27]

The Relation between impedance and reflectance

[edit]

This animation shows how impedances with positive real part are mapped to reflectances with less than unit magnitude.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Okamura [岡村], Fumiyoshi [史良] / Shirō [獅郎] (August 1959) [1959-04-04]. "Sumisuchāto wa nihonjin no dokusōde wanai ka" スミスチャートは日本人の独創ではないか ["Smith Chart" May Have Origin in Japan] (PDF). The Journal of the Institute of Electrical Communication Engineers of Japan [電気通信学会雑誌] (in Japanese). 1959 (8). Tokyo, Japan: Institute of Electrical Communication Engineers of Japan [電気通信学会]: 768–769 (44–45). ISSN 0914-5273. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-11-16. (2 pages) (NB. The article lists the author's given name as 史良 in Japanese, which would translate as "Fumiyoshi", whereas the English footnote in the same article transscribed it as "Shirō", which would be associated with 獅郎 in Japanese.)

- ^ Kenichi [伊藤健], Ito [一著] (1999-11-01). Inpīdansu no hanashi インピーダンスのはなし [The story of impedance]. Science and Technology (in Japanese) (1 ed.). Nikkan Kogyo Shimbun [日刊工業新聞社]. p. 26. ISBN 4-526-04463-6. EAN 978-4-526-04463-2. 1923054018007. (4+xi+1+207+3+4 pages)

- ^ Mori [森], Kunihiko [邦彦] (2013). "The Mizuhashi-Smith Chart". morikuni_net. Archived from the original on 2013-03-03. Retrieved 2023-06-24.

- ^ a b c Kurochkin [Курочкин], Alexander Evdokimovich [Александр Евдокимович] (2009). "Diagramma Vol'perta – Smita. Raschet i analiz kharakteristik usiliteley radiosignalov" Диаграмма Вольперта – Смита. Расчет и анализ характеристик усилителей радиосигналов [The Volpert–Smith diagram. Calculation and analysis of the characteristics of amplifiers of radio signals] (PDF) (in Russian). Minsk, Belarus: Department of Radio Engineering Devices, Belarusian State University of Informatics and Radio Electronics, Ministry of Education of the Republic of Belarus educational institution. ISBN 978-9-85-488-422-6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-07-09. Retrieved 2023-07-09. p. 4:

Diagramma Smita ostayetsya odnim iz naiboleye poleznykh graficheskikh instrumentov dlya razrabotki vysokochastotnykh usilitel'nykh kaskadov. V nashey strane analogichnaya diagramma izvestna kak krugovaya nomogramma A. R. Vol'perta, kotoryy v 1939 g. nezavisimo ot Smita razrabotal i primenil yeye dlya pereschota provodimostey i soprotivleniy v otrezkakh liniy peredachi.

Диаграмма Смита остается одним из наиболее полезных графических инструментов для разработки высокочастотных усилительных каскадов. В нашей стране аналогичная диаграмма известна как круговая номограмма А. Р. Вольперта, который в 1939 г. независимо от Смита разработал и применил ее для пересчёта проводимостей и сопротивлений в отрезках линий передачи. [In our country, a similar diagram is known as a circular nomogram of A. R. Volpert, who in 1939, independently of Smith developed and applied it to recalculate conductances and resistances in segments of transmission lines.] [1][2][3] (40+1 pages) - ^ a b Salov, Mikhail (March 2022). "4. Volpert–Smith Chart". Antenna Impedance Measurement and Matching (PDF) (Application note). Texas Instruments. p. 11. SWRA726. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-06-26. Retrieved 2023-06-26. (51 pages)

- ^ Ramo, Simon "Si"; Whinnery, John Roy; Van Duzer, Theodore (1965). Fields and Waves in Communications Electronics (1 ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 35–39.

- ^ Ramo, Simon "Si"; Whinnery, John Roy; Van Duzer, Theodore (1994). "5.9. The Smith Transmission-Line Chart / 5.10. Some Uses of the Smith Chart". Fields and Waves in Communications Electronics (3 ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 236–245. ISBN 978-0-471-58551-0.

- ^ Smith, Phillip Hagar (June 1969). Written at Pine Brook, New Jersey, USA. Electronic Applications of the Smith Chart: In Waveguide, Circuit and Component Analysis (1 ed.). New York, USA: McGraw-Hill Book Company / Kay Electric Company. ISBN 0-07058930-5. LCCN 69-12411. ISBN 978-0-07058930-8. (xxvii+1+222 pages + envelope with 4 translucent plastic overlays + Kay Electric Company postcard) (NB. There is a 1983 reprint of the first edition by Robert E. Krieger Publishing Company with ISBN 978-0-89874-552-8, 0-89874-552-7, and a second edition by Noble Publishing Corporation.)

- ^ a b c d Smith, Phillip Hagar (October 2000) [1995]. Electronic Applications of the Smith Chart: In Waveguide, Circuit and Component Analysis (2 ed.). Atlanta, Georgia, USA: Noble Publishing Corporation. ISBN 1-884932-39-8. LCCN 00-045239. ISBN 978-1-884932-39-7. p. xiv:

[…] From Fleming's equation,[A] and in an effort to simplify the solution of the transmission line problem, he developed his first graphical solution in the form of a rectangular plot. […] the diagram gradually evolved through a series of steps. The first rectangular chart was limited by the range of data it could accommodate. He was aware of the limitations and kept working on the problem until some time in 1936, when he developed a new diagram that eliminated most of the difficulties. The new chart was a special polar coordinate form in which all values of impedance components could be accommodated. The data for this diagram was scaled from the earlier rectangular diagram. The impedance coordinates in this case were not orthogonal and were not true circles, but, in the form chosen, the standing wave ratio was linear. The chart closely resembled what ultimately became the final result. Phil, however, suspected that a grid made up of a system of orthogonal circles might be more practical. He felt it would have distinct advantages, particularly as regards reproducibility. With this in mind, he spoke to two of his co-workers, E.B. Ferrell and J.W. McRae. Because they were familiar with the principles of conformal mapping, they were able to develop the transformation whereby all data from zero to infinity could be accommodated. Fortunately, curves of constant standing wave ratio, constant attenuation and constant reflection coefficient were all circles coaxial with the center of the diagram. The scales for these values, while not linear, were entirely satisfactory. A diagram designed along these lines was constructed in early 1937. It was essentially the form still being used today. Smith approached a number of technical magazines with regard to publication of the Chart, but acceptance was slow. There were not many technical magazines at the time, and none in the microwave area. However, in January of 1939, after a delay of two years, the article was printed in Electronics magazine. […]

(xxvi+237+1 pages + envelope with 4 translucent plastic overlays) (NB. There is a 2006 reprint of the second edition by SciTech Publishing, Inc. under the same ISBN and LCCN.) - ^ "Impedance Matching and Smith Chart Impedance" (Application note). Maxim Integrated Products, Inc. 2012 [2002-07-22]. Tutorial 742. Archived from the original on 2023-07-09. Retrieved 2023-07-09.[4] (18 pages) (NB. A previous version of this article appeared in the July 2000 issue of RF Design.)

- ^ Voltmer, David (2007-08-17). "8.2. The Smith Chart". In Balanis, Constantine A. (ed.). Fundamentals Of Electromagnetics 2. Quasistatics And Waves. Synthesis Lectures On Computational Electromagnetics. Vol. 2 (1 ed.). Morgan & Claypool. pp. 135–141 [135]. doi:10.2200/S00078ED1V01Y200612CEM015. ISBN 978-1-59829172-8. ISSN 1932-1716. S2CID 9045052. ISBN 1-59829172-6. LoC 1932-1252. MOBK081-FM. Retrieved 2023-06-25. p. 135:

Though Volpert of the Soviet Union and Mizuhashi of Japan proposed essentially the same chart during the same year, Smith received the recognition.

- ^ "Smith Chart". ETHW.org. 2018-02-26. Archived from the original on 2023-07-08. Retrieved 2021-03-30.

- ^ Mizuhashi [水橋], Tōsaku [東作] (December 1937) [1937-11-19]. "Sì duānzǐ huílù no inpīdansu hensei to seigō kairo no riron" 四端子回路のインピーダンス変成と整合回路の理論 [Theory of Four-Terminals Impedance Transformation Circuit and Matching Circuit] (PDF). The Journal of the Institute of Electrical Communication Engineers of Japan [電気通信学会雑誌] (in Japanese). 1937 (12). Institute of Electrical Communication Engineers of Japan [電気通信学会]: 1053–1058 (29–34). ISSN 0914-5273. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-11-16. (6 pages)

- ^ Volpert [Во́льперт], Amiel Rafailovich [Амиэ́ль Рафаи́лович] [in Russian] (February 1940). "Nomogramma dlya rascheta dlinnykh liniy" Номограмма для расчета длинных линий [Nomogram for calculating long lines]. Производственно-технический бюллетень (Proizvodstvenno-tekhnicheskiy byulleten') [Industrial and technical bulletin] (in Russian). Vol. 1940, no. 2. Leningrad, СССР: НКЭП. pp. 14–18. (5 pages)

- ^ a b c Smith, Phillip Hagar (January 1939). "Transmission Line Calculator - A "cut-out" calculator for determining impedance and attenuation, in terms of the length of open-wire transmission lines" (PDF). electronics - radio, communication, industrial applications of electron tubes ... engineering and manufacture. Vol. 12, no. 1. New York, USA: McGraw-Hill Publishing Company, Inc. pp. 29–31. ISSN 0013-5070. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-07-08. Retrieved 2023-07-09. (3 pages)

- ^ a b Smith, Phillip Hagar (January 1944). "An Improved Transmission Line Calculator - An extension of the "calculator" originally published in ELECTRONICS in January 1939. New parameters have been added and accuracy has been improved" (PDF). electronics. Vol. 17, no. 1. New York, USA: McGraw-Hill Publishing Company, Inc. pp. 130–133, 318, 320, 322, 324–325. ISSN 0013-5070. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-01-31. Retrieved 2023-07-09. (4+5 pages)

- ^ a b Inan, Aziz S. (2005-07-03). Written at School of Engineering, University of Portland, Portland, Oregon, USA. Remembering Phillip H. Smith on his 100th Birthday (PDF). 2005 IEEE Antennas and Propagation Society International Symposium Digest. Vol. 3B. Washington, D.C., USA: IEEE Antennas and Propagation Society. pp. 129–132. doi:10.1109/APS.2005.1552450. eISSN 1947-1491. ISBN 0-7803-8883-6. ISSN 1522-3965. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-07-02. Retrieved 2023-07-02. (NB. This is a corrected version of the originally published paper.)

- ^ Linton, Jr., R. L. (January 1950). Written at Antenna Laboratory, University of California, Berkeley, California, USA. "Graph for Smith Chart" (PDF). electronics. Vol. 23, no. 1. New York, USA: McGraw-Hill Publishing Company, Inc. pp. 123, 158. ISSN 0013-5070. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-01-31. Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ "Impedance Measurement-Smith Chart with Example Plotted" (PDF). General Radio Experimenter. Vol. XXV, no. 6. Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: General Radio Company. November 1950. pp. 5–7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-07-22. Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ Pozar, David Michael (2005). Microwave Engineering (3 ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 64–71. ISBN 0-471-44878-8.

- ^ a b c Gonzalez, Guillermo (1997). Microwave Transistor Amplifiers Analysis and Design (2 ed.). New Jersey, USA: Prentice Hall. pp. 93–103. ISBN 0-13-254335-4.

- ^ Bevelacqua, Peter Joseph (2013-01-11) [2010]. "The Smith Chart". www.antenna-theory.com. Archived from the original on 2023-07-08. Retrieved 2023-07-09.

- ^ "Antenna Matching with a Vector Network Analyzer". Tek. Tektronix, Inc. 2017-10-06. Archived from the original on 2023-07-08. Retrieved 2023-07-09.

- ^ Hayt, Jr., William Hart [at Wikidata] (1981). Engineering Electromagnetics (4 ed.). McGraw-Hill, Inc. pp. 428–433. ISBN 0-07-027395-2. (527 pages)

- ^ Davidson, Colin William (1989). Transmission Lines for Communications with CAD Programs (2 ed.). Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK: Macmillan Education Ltd. pp. 80–85. ISBN 0-333-47398-1. ark:/13960/s2dzmfrhg24. Retrieved 2023-07-09. (viii+244 pages)

- ^ a b Muller, Andrei A.; Soto Pacheco, Pablo; Dascălu, Dan [in Romanian]; Neculoiu, Dan; Boria, Vicente E. (2011). "A 3D Smith chart based on the Riemann sphere for active and passive microwave circuits". IEEE Microwave and Wireless Components Letters. 21 (6). IEEE Microwave Theory and Techniques Society: 286–288. doi:10.1109/LMWC.2011.2132697. hdl:10251/55107. ISSN 1531-1309. S2CID 38953650.

- ^ Muller, Andrei A.; Asavei, Victor; Moldoveanu, Alin; Sanabria-Codesal, Esther; Khadar, Riyaz A.; Popescu, Cornel; Dascălu, Dan [in Romanian]; Ionescu, Adrian M. (November 2020). "The 3D Smith Chart: From Theory to Experimental Reality". IEEE Microwave Magazine. 21 (11). IEEE Microwave Theory and Techniques Society: 22–35. doi:10.1109/MMM.2020.3014984. ISSN 1527-3342. S2CID 222296721.

Further reading

[edit]- Campbell, George Ashley (April 1911). "Cisoidal oscillations" (PDF). Proceedings of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers. XXX (1–6). American Institute of Electrical Engineers: 789–824 [Fig. 13 on p. 810]. doi:10.1109/PAIEE.1911.6659711. S2CID 51647814. Retrieved 2023-06-24. (37 pages) (NB. Includes an early graphical depiction of something similar to a Smith chart decades before Mizuhashi, Volpert and Smith published their works.)

- Fleming, John Ambrose (January 1912) [May 1911]. The Propagation of Electric Currents in Telephone and Telegraph Conductors: A Course of Post-graduate Lectures Delivered Before the University of London (revised 2nd ed.). University College, London, UK: Constable & Company Ltd. ark:/13960/t3bz6211d. Retrieved 2023-07-23. (xiv+316 pages)

- Krauss, Herbert L. (September 1949). "Transmission Line Charts". Electrical Engineering. Vol. 68, no. 9. pp. 766–774 [767]. doi:10.1109/EE.1949.6444963. eISSN 2376-7804. ISSN 0095-9197.

- Lee, Donald (2013-01-30). "Smith Chart Tuning, Part I". SOC Business Unit, Advantest Test Cell Innovations, Advantest Corporation. Archived from the original on 2023-07-09. Retrieved 2023-07-09. (29 pages)

- Gamblin, Trevor (2015-07-23). "Mathematical Construction and Properties of the Smith Chart". allaboutcircuits.com. Archived from the original on 2023-07-09. Retrieved 2023-07-09.

- Staples, John (2015). "Impedance Matching and Smith Charts" (PDF). U.S. Particle Accelerator School (USPAS). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-07-09. Retrieved 2023-07-09. (27 pages)

External links

[edit]- "Excel Smith chart". excelhero.com. August 2010. Non-commercial, interactive Smith Chart that looks best in Excel 2007+.

- "SimSmith". ae6ty.com. Non-commercial, available for Windows, Mac, and Linux. Many Smith chart tutorial videos. No circuit size restrictions. Not limited to ladder circuits.

- "Smith v3". fritz.dellsperger.net. Archived from the original on 2015-03-04. Commercial and free Smith chart for Windows

- "QuickSmith". github.com/niyeradori. 2021-11-02. Free web based Smith Chart Educational tool available on GitHub.

- "3D Smith chart tool". 3dsmithchart.com. 2D and 3D Smith chart generalized tool for active and passive circuits (free for academia/education).

![{\displaystyle \Gamma =c+jd=\left[{\frac {a^{2}+b^{2}-1}{\,(a+1)^{2}+b^{2}\,}}\right]+j\left[{\frac {2b}{\,(a+1)^{2}+b^{2}\,}}\right]=\left[1+{\frac {-2(a+1)}{\,(a+1)^{2}+b^{2}\,}}\right]+j\left[{\frac {+2b}{\,(a+1)^{2}+b^{2}\,}}\right]\,.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3d746481696441f9a4db1c799ce6db12ba5613f3)

![{\displaystyle \Gamma =c+jd=\left[{\frac {1-m^{2}-n^{2}}{\,(m+1)^{2}+n^{2}\,}}\right]+j\left[{\frac {-2n}{\,(m+1)^{2}+n^{2}\,}}\right]=\left[{\frac {2(m+1)}{\,(m+1)^{2}+n^{2}\,}}-1\right]+j\left[{\frac {-2n}{\,(m+1)^{2}+n^{2}\,}}\right]~.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ee40d10d3d9805d30f5dfe7eab2b93ab7ba0281e)