Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Saint Petersburg

View on Wikipedia

Saint Petersburg,[c] formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad,[d] is the second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland on the Baltic Sea. With an area of 1,439 sq km (556 sq mi), Saint Petersburg is the smallest administrative division of Russia by area. The city had a population of 5,601,911 residents as of 2021,[4] with more than 6.4 million people living in the metropolitan area. Saint Petersburg is the fourth-most populous city in Europe, the most populous city on the Baltic Sea, and the world's northernmost city of more than 1 million residents. As the former capital of the Russian Empire, and a historically strategic port, it is governed as a federal city.

Key Information

The city was founded by Tsar Peter the Great on 27 May 1703 on the site of a captured Swedish fortress, and was named after the apostle Saint Peter.[8] In Russia, Saint Petersburg is historically and culturally associated with the birth of the Russian Empire and Russia's entry into modern history as a European great power.[9] It served as a capital of the Tsardom of Russia, and the subsequent Russian Empire, from 1712 to 1918 (being replaced by Moscow for a short period between 1728 and 1730).[10] After the October Revolution in 1917, the Bolsheviks moved their government to Moscow.[11] The city was renamed Leningrad after Lenin's death in 1924. It was the site of the siege of Leningrad during World War II, the most lethal siege in history.[12] In June 1991, only a few months before the Belovezha Accords and the dissolution of the Soviet Union, voters in a city-wide referendum supported restoring the city's original name.[13]

As Russia's cultural centre,[14] Saint Petersburg received over 15 million tourists in 2018.[15][16] It is considered an important economic, scientific, and tourism centre of Russia and Europe. In modern times, the city has the nickname of being "the Northern Capital of Russia" and is home to notable federal government bodies such as the Constitutional Court of Russia and the Heraldic Council of the President of the Russian Federation. It is also a seat for the National Library of Russia and a planned location for the Supreme Court of Russia, as well as the home to the headquarters of the Russian Navy, and the Leningrad Military District of the Russian Armed Forces. The Historic Centre of Saint Petersburg and Related Groups of Monuments constitute a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Saint Petersburg is home to the Hermitage (one of the largest art museums in the world), the Lakhta Center (the tallest skyscraper in Europe), and was one of the host cities of the 2018 FIFA World Cup and the UEFA Euro 2020.

Toponymy

[edit]

The name day of Tsar Peter the Great falls on 29 June, when the Russian Orthodox Church observes the memory of apostles Peter and Paul. The consecration of the small wooden church in their names (its construction began at the same time as the citadel) made them the heavenly patrons of the Peter and Paul Fortress, while Saint Peter at the same time became the eponym of the whole city. When in June 1703 Peter the Great renamed the site after Saint Peter, he did not issue a naming act that established an official spelling; even in his own letters he used diverse spellings, such as Санктьпетерсьбурк (Sanktpetersburk), emulating German Sankt Petersburg, and Сантпитербурх (Santpiterburkh), emulating Dutch Sint-Pietersburgh, as Peter was multilingual and a Hollandophile. The name was later normalized and russified to Санкт-Петербург (Sankt-Peterburg).[17][18][19]

A former spelling of the city's name in English was Saint Petersburgh. This spelling survives in the name of a street in the Bayswater district of London, near St Sophia's Cathedral, named after a visit by the Tsar to London in 1814.[20]

A 14 to 15-letter-long name, composed of the three roots, proved too cumbersome, and many shortened versions were used. The first General Governor of the city Menshikov is maybe also the author of the first nickname of Petersburg, which he called Петри (Petri). It took some years until the known Russian spelling of this name finally settled. In 1740s Mikhail Lomonosov uses a derivative of Greek: Πετρόπολις (Петрополис, Petropolis) in a Russified form Petropol' (Петрополь). A combo Piterpol (Питерпол) also appears at this time.[21] In any case, eventually the usage of the prefix "Sankt-" ceased except for the formal official documents, where a three-letter abbreviation "СПб" (SPb) was very widely used as well.

In the 1830s Alexander Pushkin translated the "foreign" city name of "Saint Petersburg" to the more Russian Petrograd (Russian: Петроград, IPA: [pʲɪtrɐˈgrat])[e] in one of his poems. However, it was only on 31 August [O.S. 18 August] 1914, after the war with Germany had begun, that Tsar Nicholas II renamed the city Petrograd in order to expunge the German words Sankt and Burg.[22] Since the prefix "Saint" was omitted,[23] this act also changed the eponym and the "patron" of the city from Saint Peter to Peter the Great, its founder.[19] On 26 January 1924, shortly after the death of Vladimir Lenin, it was renamed to Leningrad (Russian: Ленинград, IPA: [lʲɪnʲɪnˈgrat]), meaning 'Lenin City'. On 6 September 1991, the original name, Sankt-Peterburg, was returned by citywide referendum. Today, in English, the city is known as Saint Petersburg. Residents often refer to the city by its shortened nickname, Piter (Russian: Питер, IPA: [ˈpʲitʲɪr]).

After the October Revolution, the name Red Petrograd (Красный Петроград, Krasny Petrograd) was often used in newspapers and other prints until the city was renamed Leningrad in January 1924.

The referendum on restoring the historic name was held on 12 June 1991, with 55% of voters supporting "Saint Petersburg" and 43% supporting "Leningrad".[13] Renaming the city Petrograd was not an option. This change officially took effect on 6 September 1991.[24] Meanwhile, the oblast which surrounds Saint Petersburg is still named Leningrad.

Having passed the role of capital to Petersburg, Moscow never relinquished the title of "capital", being called pervoprestolnaya ('first throned') for 200 years. An equivalent name for Petersburg, the "Northern Capital", has re-entered usage today since several federal institutions were recently moved from Moscow to Saint Petersburg. Solemn descriptive names like "the city of three revolutions" and "the cradle of the October Revolution" used in the Soviet era are reminders of the pivotal events in national history that occurred here. Petropolis is a translation of a city name to Greek, and is also a kind of descriptive name: Πέτρ- is a Greek root for 'stone', so the "city from stone" emphasizes the material that had been forcibly made obligatory for construction from the first years of the city[21] (a modern Greek translation is Αγία Πετρούπολη, Agia Petroupoli).[25]

Saint Petersburg has been traditionally called the "Window to Europe" and the "Window to the West" by the Russians.[26][27] The city is the northernmost metropolis with more than 1 million people in the world, and is also often described as the "Venice of the North" or the "Russian Venice" due to its many water corridors, as the city is built on swamp and water. Furthermore, it has strongly Western European-inspired architecture and culture, which is combined with the city's Russian heritage.[28][29][30] Another nickname of Saint Petersburg is "The City of the White Nights" because of a natural phenomenon which arises due to the closeness to the polar region and ensures that in summer the night skies of the city do not get completely dark for a month.[31][32] The city is also often called the "Northern Palmyra", due to its extravagant architecture.[33]

History

[edit]Imperial era (1703–1917)

[edit]

Swedish colonists built Nyenskans, a fortress at the mouth of the Neva River in 1611, which was later called Ingermanland. The small town of Nyen grew up around the fort. Before the 17th century, this area was inhabited by Finnic Izhorians and Votians. The Ingrian Finns moved to the region from the provinces of Karelia and Savonia during the Swedish rule. There was also some Estonian, Karelian, Russian and German population in the area.[34][35]

At the end of the 17th century, Peter the Great, who was interested in seafaring and maritime affairs, wanted Russia to gain a seaport to trade with the rest of Europe.[36] He needed a better seaport than the country's main one at the time, Arkhangelsk, which was on the White Sea in the far north and closed to shipping during the winter.

On 12 May [O.S. 1 May] 1703, during the Great Northern War, Peter the Great captured Nyenskans and soon replaced the fortress.[37] On 27 May [O.S. 16 May] 1703,[38] closer to the estuary (5 km (3 mi) inland from the gulf), on Zayachy (Hare) Island, he laid down the Peter and Paul Fortress, which became the first brick and stone building of the new city.[39]

The city was built by conscripted peasants from all over Russia; in some years several Swedish prisoners of war were also involved under the supervision of Alexander Menshikov.[40] Tens of thousands of serfs died while building the city.[41] Later, the city became the centre of the Saint Petersburg Governorate. Peter moved the capital from Moscow to Saint Petersburg in 1712, nine years before the Treaty of Nystad of 1721 ended the war. He referred to Saint Petersburg as the capital (or seat of government) as early as 1704.[36]

During its first few years, the city developed around Trinity Square on the right bank of the Neva, near the Peter and Paul Fortress. However, Saint Petersburg soon started to be built out according to a plan. By 1716, the Swiss Italian Domenico Trezzini had elaborated a project whereby the city centre would be on Vasilyevsky Island and shaped by a rectangular grid of canals. The project was not completed but is evident in the layout of the streets. In 1716, Peter the Great appointed Frenchman Jean-Baptiste Alexandre Le Blond as the chief architect of Saint Petersburg.[42]

The style of Petrine Baroque, developed by Trezzini and other architects and exemplified by such buildings as the Menshikov Palace, Kunstkamera, Peter and Paul Cathedral, Twelve Collegia, became prominent in the city architecture of the early 18th century. In 1724, the Academy of Sciences, University, and the Academic Gymnasium were established in Saint Petersburg by Peter the Great.

In 1725, Peter died at age fifty-two. His endeavors to modernize Russia had been opposed by the Russian nobility. There were several attempts on his life and a treason case involving his son.[43] In 1728, Peter II of Russia moved his seat back to Moscow. But four years later, in 1732, under Empress Anna of Russia, Saint Petersburg was again designated as the capital of the Russian Empire. It remained the seat of the Romanov dynasty and the Imperial Court of the Russian tsars, as well as the seat of the Russian government, for another 186 years until the communist revolution of 1917.

In 1736–1737, the city suffered from catastrophic fires. To rebuild the damaged boroughs, a committee under Burkhard Christoph von Münnich commissioned a new plan in 1737. The city was divided into five boroughs, and the city centre was moved to the Admiralty borough, on the east bank between the Neva and Fontanka.

It developed along three radial streets, which meet at the Admiralty building and are now known as Nevsky Prospect (which is considered the main street of the city), Gorokhovaya Street, and Voznesensky Avenue. Baroque architecture became dominant in the city during the first sixty years, culminating in the Elizabethan Baroque, represented most notably by Italian Bartolomeo Rastrelli with such buildings as the Winter Palace. In the 1760s, Baroque architecture was succeeded by neoclassical architecture.

Established in 1762, the Commission of Stone Buildings of Moscow and Saint Petersburg ruled that no structure in the city could be higher than the Winter Palace and prohibited spacing between buildings. During the reign of Catherine the Great in the 1760s–1780s, the banks of the Neva were lined with granite embankments.

However, it was not until 1850 that the first permanent bridge across the Neva, Annunciation Bridge, was allowed to open. Before that, only pontoon bridges were allowed. Obvodny Canal (dug in 1769–1833) became the southern limit of the city.

The most prominent neoclassical and Empire-style architects in Saint Petersburg included:

- Jean-Baptiste Vallin de la Mothe (Imperial Academy of Arts, Small Hermitage, Gostiny Dvor, New Holland Arch, Catholic Church of St. Catherine)

- Antonio Rinaldi (Marble Palace)

- Yury Felten (Old Hermitage, Chesme Church)

- Giacomo Quarenghi (Academy of Sciences, Hermitage Theatre, Yusupov Palace)

- Andrey Voronikhin (Mining Institute, Kazan Cathedral)

- Andreyan Zakharov (Admiralty building)

- Jean-François Thomas de Thomon (Spit of Vasilievsky Island)

- Carlo Rossi (Yelagin Palace, Mikhailovsky Palace, Alexandrine Theatre, Senate and Synod Buildings, General staff Building, design of many streets and squares)

- Vasily Stasov (Moscow Triumphal Gate, Trinity Cathedral)

- Auguste de Montferrand (Saint Isaac's Cathedral, Alexander Column)

In 1810, Alexander I established the first engineering higher education, the Saint Petersburg Main military engineering School in Saint Petersburg. Many monuments commemorate the Russian victory over Napoleonic France in the Patriotic War of 1812, including the Alexander Column by Montferrand, erected in 1834, and the Narva Triumphal Arch.

In 1825, the suppressed Decembrist revolt against Nicholas I took place on the Senate Square in the city, a day after Nicholas assumed the throne.

By the 1840s, neoclassical architecture had given way to various romanticist styles, which dominated until the 1890s, represented by such architects as Andrei Stackenschneider (Mariinsky Palace, Beloselsky-Belozersky Palace, Nicholas Palace, New Michael Palace) and Konstantin Thon (Moskovsky railway station).

With the emancipation of the serfs undertaken by Alexander II in 1861 and an Industrial Revolution, the influx of former peasants into the capital increased greatly. Poor boroughs spontaneously developed on the outskirts of the city. Saint Petersburg surpassed Moscow in population and industrial growth; it became one of the largest industrial cities in Europe, with a major naval base (in Kronstadt), the Neva River, and a seaport on the Baltic.

The names of Saints Peter and Paul, bestowed upon the original city's citadel and its cathedral (from 1725 – a burial vault of Russian emperors) coincidentally were the names of the first two assassinated Russian emperors, Peter III (1762, supposedly killed in a conspiracy led by his wife, Catherine the Great) and Paul I (1801, Nikolay Alexandrovich Zubov and other conspirators who brought to power Alexander I, the son of their victim). The third emperor's assassination took place in Saint Petersburg in 1881 when Alexander II was murdered by terrorists (see the Church of the Savior on Spilled Blood).

The Revolution of 1905 began in Saint Petersburg and spread rapidly into the provinces.

On 1 September 1914, after the outbreak of World War I, the Imperial government renamed the city Petrograd,[22] meaning "Peter's City", to remove the German words Sankt and Burg.

Revolution and Soviet era (1917–1941)

[edit]In March 1917, during the February Revolution Nicholas II abdicated for himself and on behalf of his son, ending the Russian monarchy and over three hundred years of Romanov dynastic rule.

On 7 November [O.S. 25 October] 1917, the Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, stormed the Winter Palace in an event known thereafter as the October Revolution, which led to the end of the social-democratic provisional government, the transfer of all political power to the Soviets, and the rise of the Communist Party.[44] After that the city acquired a new descriptive name, "the city of three revolutions",[45] referring to the three major developments in the political history of Russia of the early 20th century.

In September and October 1917, German troops invaded the West Estonian archipelago and threatened Petrograd with bombardment and invasion. On 12 March 1918, Lenin transferred the government of Soviet Russia to Moscow, to keep it away from the state border. During the Russian Civil War, in mid-1919, Russian anti-communist forces with the help of Estonians attempted to capture the city, but Leon Trotsky mobilized the army and forced them to retreat to Estonia.

On 26 January 1924, five days after Lenin's death, Petrograd was renamed Leningrad.[46] Later many streets and other toponyms were renamed accordingly, with names in honour of communist figures replacing historic names given centuries before. The city has over 230 places associated with the life and activities of Lenin. Some of them were turned into museums,[47] including the cruiser Aurora– a symbol of the October Revolution and the oldest ship in the Russian Navy.

In the 1920s and 1930s, the poor outskirts were reconstructed into regularly planned boroughs. Constructivist architecture flourished around that time. Housing became a government-provided amenity; many "bourgeois" apartments were so large that numerous families were assigned to what were called "communal" apartments (kommunalkas). By the 1930s, 68% of the population lived in such housing under very poor conditions. In 1935, a new general plan was outlined, whereby the city should expand to the south. Constructivism was rejected in favour of a more pompous Stalinist architecture. Moving the city centre further from the border with Finland, Stalin adopted a plan to build a new city hall with a huge adjacent square at the southern end of Moskovsky Prospekt, designated as the new main street of Leningrad. After the Winter (Soviet-Finnish) war in 1939–1940, the Soviet–Finnish border moved northwards. Nevsky Prospekt with Palace Square maintained the functions and the role of a city centre.

In December 1931, Leningrad was administratively separated from Leningrad Oblast. At that time, it included the Leningrad Suburban District, some parts of which were transferred back to Leningrad Oblast in 1936 and turned into Vsevolozhsky District, Krasnoselsky District, Pargolovsky District and Slutsky District (renamed Pavlovsky District in 1944).[48]

During the Soviet era, many historic architectural monuments of the previous centuries were destroyed by the new regime for ideological reasons. While that mainly concerned churches and cathedrals, some other buildings were also demolished.[49][50][51]

On 1 December 1934, Sergey Kirov, the Bolshevik leader of Leningrad, was assassinated under suspicious circumstances, which became the pretext for the Great Purge.[52] In Leningrad, approximately 40,000 were executed during Stalin's purges.[53]

World War II (1941–1945)

[edit]

During World War II, German forces besieged Leningrad following the Axis invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941.[54] The siege lasted 872 days, or almost two and a half years,[54] from 8 September 1941 to 27 January 1944.[55]

The Siege of Leningrad proved one of the longest, most destructive, and most lethal sieges of a major city in modern history. It isolated the city from food supplies except those provided through the Road of Life across Lake Ladoga, which could not make it through until the lake froze. More than one million civilians were killed, mainly from starvation. There were incidents of cannibalism, with around 2,000 residents arrested for eating other people.[56] Many others escaped or were evacuated, so the city became largely depopulated.

On 1 May 1945, Joseph Stalin, in his Supreme Commander Order No. 20, named Leningrad, alongside Stalingrad, Sevastopol, and Odesa, hero cities of the war. A law acknowledging the honorary title of "Hero City" passed on 8 May 1965 (the 20th anniversary of the victory in the Great Patriotic War), during the Brezhnev era. The Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR awarded Leningrad as a Hero City the Order of Lenin and the Gold Star medal "for the heroic resistance of the city and tenacity of the survivors of the Siege". The Hero-City Obelisk bearing the Gold Star sign was installed in April 1985.

Post-war Soviet era (1945–1991)

[edit]

In October 1946 some territories along the northern coast of the Gulf of Finland, which had been annexed into the USSR from Finland in 1940 under the peace treaty following the Winter War, were transferred from Leningrad Oblast to Leningrad and divided into Sestroretsky District and Kurortny District. These included the town of Terijoki (renamed Zelenogorsk in 1948).[48] Leningrad and many of its suburbs were rebuilt over the post-war decades, partially according to pre-war plans. The 1948 general plan for Leningrad featured radial urban development in the north as well as in the south. In 1953, Pavlovsky District in Leningrad Oblast was abolished, and parts of its territory, including Pavlovsk, merged with Leningrad. In 1954, the settlements Levashovo, Pargolovo and Pesochny merged with Leningrad.[48]

Leningrad gave its name to the Leningrad Affair (1949–1952), a notable event in the postwar political struggle in the USSR. It was a product of rivalry between Stalin's potential successors where one side was represented by the leaders of the city Communist Party organization – the second most significant one in the country after Moscow. The entire elite leadership of Leningrad was destroyed, including the former mayor Kuznetsov, the acting mayor Pyotr Sergeevich Popkov, and all their deputies; overall, 23 leaders were sentenced to the death penalty, 181 to prison or exile (rehabilitated in 1954). About 2,000 ranking officials across the USSR were expelled from the party and the Komsomol and removed from leadership positions.[57]

The Leningrad Metro underground rapid transit system, designed before the war, opened in 1955 with its first eight stations decorated with marble and bronze. However, after Stalin died in 1953, the perceived ornamental excesses of the Stalinist architecture were abandoned. From the 1960s to the 1980s, many new residential boroughs were built on the outskirts; while the functionalist apartment blocks were nearly identical to each other, many families moved there from kommunalkas in the city centre to live in separate apartments.

Contemporary era (1991–present)

[edit]

On 12 June 1991, simultaneously with the first Russian SFSR presidential elections, the city authorities arranged for the mayoral elections and a referendum on the city's name, when the original name Saint Petersburg was restored. 66% of the total count of votes went to Anatoly Sobchak, who became the first directly elected mayor of the city.[58]

Meanwhile, economic conditions started to deteriorate as the country's people tried to adapt to major changes. For the first time since the 1940s, food rationing was introduced, and the city received humanitarian food aid from abroad.[24] This dramatic time was depicted in photographic series of Russian photographer Alexey Titarenko.[59][60] Economic conditions began to improve only at the beginning of the 21st century.[61] In 1995, a northern section of the Kirovsko-Vyborgskaya Line of the Saint Petersburg Metro was cut off by underground flooding, creating a major obstacle to the city development for almost ten years. On 13 June 1996, Saint Petersburg, alongside Leningrad Oblast and Tver Oblast, signed a power-sharing agreement with the federal government, granting it autonomy.[62] This agreement was abolished on 4 April 2002.[63]

In 1996, Vladimir Yakovlev defeated Anatoly Sobchak in the elections for the head of the city administration. The title of the city head was changed from "mayor" to "governor".[64] In 2000, Yakovlev won re-election.[65] His second term expired in 2004; the long-awaited restoration of the broken subway connection was expected to finish by that time. But in 2003, Yakovlev suddenly resigned, leaving the governor's office to Valentina Matviyenko.

The law on the election of the City Governor was changed, breaking the tradition of democratic election by universal suffrage that started in 1991. In 2006, the city legislature re-approved Matviyenko as governor. Residential building had intensified again; real-estate prices inflated greatly, which caused many new problems for the preservation of the historical part of the city.

Although the central part of the city has a UNESCO designation (there are about 8,000 architectural monuments in Petersburg), the preservation of its historical and architectural environment became controversial.[66] After 2005, the demolition of older buildings in the historical centre was permitted.[67] In 2006, Gazprom announced an ambitious project to build a skyscraper as part of the Gazprom City complex, with its main tower set to soar significantly higher than the city's most famous landmarks. The tower would be located opposite the Smolny Cathedral on the Neva river, and critics warned it could disrupt the architectural harmony of the city's landscape.[68] Urgent protests by citizens and prominent public figures of Russia against this project were not considered by Governor Valentina Matviyenko and the city authorities until December 2010, when after the statement of President Dmitry Medvedev, the city decided to find a more appropriate location for this project. In the same year, the new location for the project was relocated to Lakhta, a historical area northwest of the city centre, and the new project would be named Lakhta Center. Construction was approved by Gazprom and the city administration and commenced in 2012. The 462 m (1,516 ft) high Lakhta Center has become the first tallest skyscraper in Russia and Europe outside of Moscow.

Geography

[edit]

The area of Saint Petersburg city proper is 605.8 km2 (233.9 square miles). The area of the federal subject is 1,439 km2 (556 sq mi), which contains Saint Petersburg proper (consisting of eighty-one municipal okrugs), nine municipal towns (Kolpino, Krasnoye Selo, Kronstadt, Lomonosov, Pavlovsk, Petergof, Pushkin, Sestroretsk, Zelenogorsk), and twenty-one municipal settlements.

Petersburg is in the middle taiga lowlands along the shores of the Neva Bay of the Gulf of Finland, and islands of the river delta. The largest are Vasilyevsky Island (besides the artificial island between Obvodny canal and Fontanka, and Kotlin in the Neva Bay), Petrogradsky, Dekabristov and Krestovsky. The latter, together with Yelagin and Kamenny Island are covered mostly by parks. The Karelian Isthmus, North of the city, is a popular resort area. In the south, Saint Petersburg crosses the Baltic-Ladoga Klint and meets the Izhora Plateau.

The elevation of Saint Petersburg ranges from the sea level to its highest point of 175.9 m (577 ft) at the Orekhovaya Hill in the Duderhof Heights in the south. Part of the city's territory west of Liteyny Prospekt is no higher than 4 m (13 ft) above sea level, and has suffered from numerous floods. Floods in Saint Petersburg are triggered by a long wave in the Baltic Sea, caused by meteorological conditions, winds, and shallowness of the Neva Bay. The five most disastrous floods occurred in 1824 (4.21 m or 13 ft 10 in above sea level, during which over 300 buildings were destroyed[f]); 1924 (3.8 m, 12 ft 6 in); 1777 (3.21 m, 10 ft 6 in); 1955 (2.93 m, 9 ft 7 in); and 1975 (2.81 m, 9 ft 3 in). To prevent floods, the Saint Petersburg Dam has been constructed.[69]

Since the 18th century, the city's terrain has been raised artificially, at some places by more than 4 m (13 ft), making mergers of several islands, and changing the hydrology of the city. Besides the Neva and its tributaries, other important rivers of the federal subject of Saint Petersburg are Sestra, Okhta, and Izhora. The largest lake is Sestroretsky Razliv in the north, followed by Lakhtinsky Razliv, Suzdal Lakes, and other smaller lakes.

Due to its northerly location at c. 60° N latitude, the day length in Petersburg varies across seasons, ranging from 5 hours 53 minutes to 18 hours 50 minutes. A period from mid-May to end-July during which it doesn't get darker than nautical twilight is called the white nights.

Saint Petersburg is about 165 km (103 miles) south-east of the border with Finland, connected to it via the M10 highway (E18), along which there is also a connection to the historic city of Vyborg.

Climate

[edit]Under the Köppen climate classification, Saint Petersburg is classified as Dfb, a humid continental climate. The distinct moderating influence of Baltic Sea cyclones results in mild to hot, humid, short summers and long, moderately cold, wet winters. The climate of Saint Petersburg is close to that of Helsinki, although slightly more continental (i.e., colder in winter and warmer in summer) because of its more eastern location, while slightly less continental than that of Moscow.

The average high temperature in July is 23 °C (73 °F), and the average low temperature in February is −8.5 °C (16.7 °F); an extreme temperature of 37.1 °C (98.8 °F) occurred during the 2010 Northern Hemisphere summer heat wave. A winter low of −35.9 °C (−32.6 °F) was recorded in 1883. The average annual temperature is 5.8 °C (42.4 °F). The Neva River within the city limits usually freezes up in November–December and break-up occurs in April. From December to March, there are 118 days on average with snow cover, which reaches an average snow depth of 19 cm (7.5 in) by February.[70] The frost-free period in the city lasts on average for about 135 days. Despite St. Petersburg's northern location, its winters are warmer than Moscow's due to the Gulf of Finland and some Gulf Stream influence from Scandinavian winds that can bring temperatures slightly above freezing. The city also has a slightly warmer climate than its suburbs due to the urban heat island effect. It also has a pretty low diurnal temperature variation, especially during fall and winter. Weather conditions are quite variable all year round.[71][72]

Average annual precipitation varies across the city, averaging 660 mm (26 in) per year and reaching a maximum in late summer. Due to the cool climate, soil moisture is almost always high because of lower evapotranspiration. Air humidity is 78% on average, and there are, on average, 165 overcast days per year.

| Climate data for Saint Petersburg (1991–2020, extremes 1743–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 8.7 (47.7) |

10.2 (50.4) |

16.1 (61.0) |

25.3 (77.5) |

33.0 (91.4) |

35.9 (96.6) |

35.3 (95.5) |

37.1 (98.8) |

30.4 (86.7) |

21.0 (69.8) |

12.3 (54.1) |

10.9 (51.6) |

37.1 (98.8) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −2.5 (27.5) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

2.3 (36.1) |

9.5 (49.1) |

16.3 (61.3) |

20.5 (68.9) |

23.3 (73.9) |

21.4 (70.5) |

15.9 (60.6) |

8.7 (47.7) |

2.8 (37.0) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

9.6 (49.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −4.8 (23.4) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

5.2 (41.4) |

11.5 (52.7) |

16.1 (61.0) |

19.1 (66.4) |

17.4 (63.3) |

12.4 (54.3) |

6.2 (43.2) |

0.9 (33.6) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

6.3 (43.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −7.2 (19.0) |

−7.6 (18.3) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

1.7 (35.1) |

7.2 (45.0) |

12.2 (54.0) |

15.3 (59.5) |

13.9 (57.0) |

9.4 (48.9) |

4.1 (39.4) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

3.3 (37.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −35.9 (−32.6) |

−35.2 (−31.4) |

−29.9 (−21.8) |

−21.8 (−7.2) |

−6.6 (20.1) |

0.1 (32.2) |

4.9 (40.8) |

1.3 (34.3) |

−3.1 (26.4) |

−12.9 (8.8) |

−22.2 (−8.0) |

−34.4 (−29.9) |

−35.9 (−32.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 46 (1.8) |

36 (1.4) |

36 (1.4) |

37 (1.5) |

47 (1.9) |

69 (2.7) |

84 (3.3) |

87 (3.4) |

57 (2.2) |

64 (2.5) |

56 (2.2) |

51 (2.0) |

670 (26.4) |

| Average extreme snow depth cm (inches) | 15 (5.9) |

19 (7.5) |

14 (5.5) |

1 (0.4) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

3 (1.2) |

9 (3.5) |

19 (7.5) |

| Average rainy days | 9 | 7 | 10 | 13 | 16 | 18 | 17 | 17 | 20 | 20 | 16 | 10 | 173 |

| Average snowy days | 25 | 23 | 16 | 8 | 1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 5 | 16 | 23 | 117 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 86 | 84 | 79 | 69 | 65 | 69 | 71 | 76 | 80 | 83 | 86 | 87 | 78 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 18.9 | 45.5 | 120.5 | 177.9 | 255.6 | 254.3 | 267.7 | 228.1 | 134.8 | 61.8 | 23.0 | 8.1 | 1,596.2 |

| Source 1: Pogoda.ru.net[70] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA[73] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]

Saint Petersburg is the second-largest city in Russia. As of the 2021 Census,[4] the federal subject's population is 5,601,911 or 3.9% of the total population of Russia; up from 4,879,566 (3.4%) recorded in the 2010 Census,[74] and up from 5,023,506 recorded in the 1989 Census.[75] Over 6.4 million people reside in the metropolitan area.

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1897 | 1,264,920 | — |

| 1926 | 1,590,770 | +25.8% |

| 1939 | 3,191,304 | +100.6% |

| 1959 | 3,321,196 | +4.1% |

| 1970 | 3,949,501 | +18.9% |

| 1979 | 4,588,183 | +16.2% |

| 1989 | 5,023,506 | +9.5% |

| 2002 | 4,661,219 | −7.2% |

| 2010 | 4,879,566 | +4.7% |

| 2021 | 5,601,911 | +14.8% |

| Source: Census data | ||

Vital statistics for 2024:[76]

- Births: 47,148 (8.4 per 1,000)

- Deaths: 62,471 (11.2 per 1,000)

Total fertility rate (2024):[77]

1.26 children per woman

Life expectancy (2021):[78]

Total – 72.51 years (male – 68.23, female – 76.30)

Ethnic composition of Saint Petersburg

| Ethnicity | Year | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1939[79] | 1959[80] | 1970[81] | 1979[82] | 1989[83] | 2002[84] | 2010[84] | 2021[85] | |||||||||

| Population | % | Population | % | Population | % | Population | % | Population | % | Population | % | Population | % | Population1 | % | |

| Russians | 2,775,979 | 86.9 | 2,951,254 | 88.9 | 3,514,296 | 89.0 | 4,097,629 | 89.7 | 4,448,884 | 89.1 | 3,949,623 | 92.0 | 3,908,753 | 92.5 | 4,275,058 | 90.6 |

| Ukrainians | 54,660 | 1.7 | 68,308 | 2.1 | 97,109 | 2.5 | 117,412 | 2.6 | 150,982 | 3.0 | 87,119 | 2.0 | 64,446 | 1.5 | 29,353 | 0.6 |

| Tatars | 31,506 | 1.0 | 27,178 | 0.8 | 32,851 | 0.8 | 39,403 | 0.9 | 43,997 | 0.9 | 35,553 | 0.8 | 30,857 | 0.7 | 20,286 | 0.4 |

| Azerbaijanis | 385 | - | 855 | - | 1,576 | - | 3,171 | 0.1 | 11,804 | 0.2 | 16,613 | 0.4 | 17,717 | 0.4 | 16,406 | 0.3 |

| Belarusians | 32,353 | 1.0 | 47,004 | 1.4 | 63,799 | 1.6 | 81,575 | 1.8 | 93,564 | 1.9 | 54,484 | 1.3 | 38,136 | 0.9 | 15,545 | 0.3 |

| Armenians | 4,615 | 0.1 | 4,897 | 0.1 | 6,628 | 0.2 | 7,995 | 0.2 | 12,070 | 0.2 | 19,164 | 0.4 | 19,971 | 0.5 | 14,737 | 0.3 |

| Uzbeks | 238 | - | - | - | 1,678 | - | 1,883 | - | 7,927 | 0.2 | 2,987 | 0.1 | 20,345 | 0.5 | 12,181 | 0.3 |

| Tajiks | 61 | - | - | - | 361 | - | 473 | - | 1,917 | - | 2,449 | 0.1 | 12,072 | 0.3 | 9,573 | 0.2 |

| Jews | 201,542 | 6.3 | 168,641 | 5.1 | 162,525 | 4.1 | 142,779 | 3.1 | 106,469 | 2.1 | 36,570 | 0.9 | 24,132 | 0.6 | 9,205 | 0.2 |

| Others | 89,965 | 2.8 | 53,059 | 1.6 | 68,678 | 1.7 | 76,228 | 1.7 | 113,135 | 2.3 | 88,661 | 2.1 | 90,310 | 2.1 | 277,297 | 6.7 |

| Total | 3,191,304 | 100 | 3,321,196 | 100 | 3,949,501 | 100 | 4,588,183 | 100 | 5,023,506 | 100 | 4,661,219 | 100 | 4,879,566 | 100 | 5,601,911 | 100 |

| 1884,678 people were registered from administrative databases, and could not declare an ethnicity. It is estimated that the proportion of ethnicities in this group is the same as that of the declared group. | ||||||||||||||||

During the 20th century, the city experienced dramatic population changes. From 2.4 million residents in 1916, its population dropped to less than 740,000 by 1920 during the Russian Revolution of 1917 and Russian Civil War. The minorities of Germans, Poles, Finns, Estonians, and Latvians were almost completely transferred from Leningrad during the 1930s.[86] From 1941 to the end of 1943, population dropped from 3 million to less than 600,000, as people died in battles, starved to death or were evacuated during the Siege of Leningrad. Some evacuees returned after the siege, but most influx was due to migration from other parts of the Soviet Union. The city absorbed about 3 million people in the 1950s and grew to over 5 million in the 1980s. From 1991 to 2006, the city's population decreased to 4.6 million, while the suburban population increased due to the privatization of land and a massive move to the suburbs. Based on the 2010 census results, the population is over 4.8 million.[87][88] For the first half of 2007, the birth rate was 9.1 per 1000[89] and remained lower than the death rate (until 2012[90]); people over 65 constitute more than twenty percent of the population; and the median age is about 40 years.[91] Since 2012 the birth rate became higher than the death rate.[90] But in 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic caused a drop in birth rate, and the city population decreased to 5,395,000 people.[92]

Religion

[edit]According to various opinion polls, more than half of the residents of Saint Petersburg "believe in God" (up to 67% according to VTsIOM data for 2002).

Among the believers, the overwhelming majority of the residents of the city are Orthodox (57.5%), followed by small minority communities of Muslims (0.7%), Protestants (0.6%), and Catholics (0.5%), and Buddhists (0.1%).[93]

In total, roughly 59% of the population of the city is Christian, of which over 90% are Orthodox.[93] Non-Abrahamic religions and other faiths are represented by only 1.2% of the total population.[93]

There are 268 communities of confessions and religious associations in the city: the Russian Orthodox Church (130 associations), Pentecostalism (23 associations), the Lutheranism (19 associations), Baptism (13 associations), as well as Old Believers, Roman Catholic Church, Armenian Apostolic Church, Georgian Orthodox Church, Seventh-day Adventist Church, Judaism, Buddhist, Muslim, Bahá'í and others.[93]

229 religious buildings in the city are owned or run by religious associations. Among them are architectural monuments of federal significance. The oldest cathedral in the city is the Peter and Paul Cathedral, built between 1712 and 1733, and the largest is the Kazan Cathedral, completed in 1811.

Government

[edit]

Saint Petersburg is a federal subject of Russia (a federal city).[96] The political life of Saint Petersburg is regulated by the Charter of Saint Petersburg adopted by the city legislature in 1998.[97] The superior executive body is the Saint Petersburg City Administration, led by the city governor (mayor before 1996). Saint Petersburg has a single-chamber legislature, the Saint Petersburg Legislative Assembly, which is the city's regional parliament.

According to the federal law passed in 2004, heads of federal subjects, including the governor of Saint Petersburg, were nominated by the President of Russia and approved by local legislatures. Should the legislature disapprove the nominee, the President could dissolve it. The former governor, Valentina Matviyenko, was approved according to the new system in December 2006. She was the only woman governor in all of Russia until her resignation on 22 August 2011. Matviyenko stood for elections as a member of the Regional Council of Saint Petersburg and won comprehensively with allegations of rigging and ballot stuffing by the opposition. Russian President Dmitry Medvedev has already backed her for the position of Speaker to the Federation Council, and her election qualifies her for that job. After her resignation, Georgy Poltavchenko was appointed as the new acting governor the same day. In 2012, following passage of a new federal law,[98] restoring direct elections of heads of federal subjects, the city charter was again amended to provide for direct elections of governor.[99] On 3 October 2018, Poltavchenko resigned, and Alexander Beglov was appointed acting governor.[100]

Saint Petersburg is also the unofficial, de facto administrative centre of Leningrad Oblast (a separate federal subject), and of the Northwestern Federal District.[101] Saint Petersburg and Leningrad Oblast share several local departments of federal executive agencies and courts, such as court of arbitration, police, FSB, postal service, drug enforcement administration, penitentiary service, federal registration service, and other federal services.

The Constitutional Court of Russia moved to Saint Petersburg from Moscow in May 2008. The relocation of the Supreme Court of Russia from Moscow to Saint Petersburg has been planned since 2014.

Administrative divisions

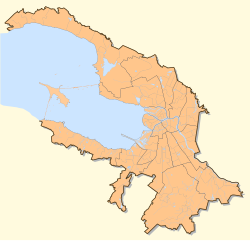

[edit]| Saint Petersburg is divided into 18 administrative districts: |  | |

| Within the boundaries of the districts, there are 111 intra-city municipalities, 81 municipal districts, nine cities (Zelenogorsk, Kolpino, Krasnoe Selo, Kronstadt, Lomonosov, Pavlovsk, Petergof, Pushkin and Sestroretsk) and 21 villages.[102] | ||

Economy

[edit]

Saint Petersburg is a major trade gateway, serving as the financial and industrial centre of Russia, with specializations in oil and gas trade; shipbuilding yards; aerospace industry; technology, including radio, electronics, software, and computers; machine building, heavy machinery and transport, including tanks and other military equipment; mining; instrument manufacture; ferrous and nonferrous metallurgy (production of aluminium alloys); chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and medical equipment; publishing and printing; food and catering; wholesale and retail; textile and apparel industries; and many other businesses. It was also home to Lessner, one of Russia's two pioneering automobile manufacturers (along with Russo-Baltic); it was founded by machine tool and boilermaker G.A. Lessner in 1904, with designs by Boris Loutsky, and it survived until 1910.[103]

Ten percent of the world's power turbines are made there at the LMZ, which built over two thousand turbines for power plants across the world.[citation needed] Major local industries are Admiralty Shipyard, Baltic Shipyard, LOMO, Kirov Plant, Elektrosila, Izhorskiye Zavody; also registered in Saint Petersburg are Sovkomflot, Petersburg Fuel Company and SIBUR among other major Russian and international companies.

The Port of Saint Petersburg has three large cargo terminals, Bolshoi Port Saint Petersburg, Kronstadt, and Lomonosov terminal.[104] International cruise liners have been served at the passenger port at Morskoy Vokzal on the south-west of Vasilyevsky Island. In 2008, the first two berths opened at the New Passenger Port on the west of the island.[105] The new passenger terminal is part of the city's "Marine Facade" development project[106] and was due to have seven berths in operation by 2010.[needs update]

A complex system of riverports on both banks of the Neva River are interconnected with the system of seaports, thus making Saint Petersburg the main link between the Baltic Sea and the rest of Russia through the Volga–Baltic Waterway.

The Saint Petersburg Mint (Monetny Dvor), founded in 1724, is one of the largest mints in the world. It mints Russian coins, medals, and badges. Saint Petersburg is also home to the oldest and largest Russian foundry, Monumentskulptura, which made thousands of sculptures and statues that now grace the public parks of Saint Petersburg and many other cities.[citation needed] Monuments and bronze statues of the Tsars, as well as other important historic figures and dignitaries, and other world-famous monuments, such as the sculptures by Peter Clodt von Jürgensburg, Paolo Troubetzkoy, Mark Antokolsky, and others, were made there.[citation needed]

In 2007, Toyota opened a Camry plant after investing 5 billion rubles (approx. US$200 million) in Shushary,[citation needed] one of the southern suburbs of Saint Petersburg. Opel, Hyundai and Nissan have also signed deals with the Russian government to build their automotive plants in Saint Petersburg.[citation needed] The automotive and auto-parts industry is on the rise there during the last decade.[which?]

Saint Petersburg has a large brewery and distillery industry. Known as Russia's "beer capital" due to the supply and quality of local water, its five large breweries account for over 30% of the country's domestic beer production. They include Europe's second-largest brewery Baltika, Vena (both operated by BBH), Heineken Brewery, Stepan Razin (both by Heineken) and Tinkoff brewery (SUN-InBev).

The city's many local distilleries produce a broad range of vodka brands. The oldest one is LIVIZ (founded in 1897). Among the youngest is Russian Standard Vodka introduced in Moscow in 1998, which opened in 2006 a new $60 million distillery in Petersburg (an area of 30,000 m2 (320,000 sq ft), production rate of 22,500 bottles per hour). In 2007, this brand was exported to over 70 countries.[107]

Saint Petersburg has the second largest construction industry in Russia, including commercial, housing, and road construction.

In 2006, Saint Petersburg's city budget was 180 billion rubles (about US$7 billion at 2006 exchange rates).[108] The federal subject's Gross Regional Product as of 2016[update] was 3.7 trillion Russian rubles (or around US$70 billion), ranked 2nd in Russia, after Moscow[109] and per capita of US$13,000, ranked 12th among Russia's federal subjects,[110] contributed mostly by wholesale and retail trade and repair services (24.7%) as well as processing industry (20.9%) and transportation and telecommunications (15.1%).[111]

Budget revenues of the city in 2009 amounted to 294.3 billion rubles (about US$10.044 billion at 2009 exchange rates), expenses – 336.3 billion rubles (about US$11.477 billion at 2009 exchange rates). The budget deficit amounted to about 42 billion rubles[112] (about US$1.433 billion at 2009 exchange rates).

In 2015, St. Petersburg was ranked in 4th place economically amongst all federal subjects of the Russian Federation, surpassed only by Moscow, the Tyumen and Moscow Region.[113]

Cityscape

[edit]

The historic architecture of Saint Petersburg's city centre, mostly Baroque and Neoclassical buildings of the 18th and 19th centuries, has been largely preserved; although a number of buildings were demolished after the Bolsheviks' seizure of power, during the Siege of Leningrad and in recent years.[citation needed] The oldest of the remaining building is a wooden house built for Peter I in 1703 on the shore of the Neva near Trinity Square. Since 1991, the Historic Centre of Saint Petersburg and Related Groups of Monuments in Saint Petersburg and Leningrad Oblast have been listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site.

The ensemble of Peter and Paul Fortress with the Peter and Paul Cathedral takes a dominant position on Zayachy Island along the right bank of the Neva River. Each noon, a cannon fires a blank shot from the fortress. The Saint Petersburg Mosque, the largest mosque in Europe when opened in 1913, is on the right bank nearby. The Spit of Vasilievsky Island, which splits the river into two largest armlets, the Bolshaya Neva and Malaya Neva, is connected to the northern bank (Petrogradsky Island) via the Exchange Bridge and occupied by the Old Saint Petersburg Stock Exchange and Rostral Columns. The southern coast of Vasilyevsky Island along the Bolshaya Neva features some of the city's oldest buildings, dating from the 18th century, including the Kunstkamera, Twelve Collegia, Menshikov Palace, and Imperial Academy of Arts. It hosts one of two campuses of Saint Petersburg State University.

On the southern, left bank of the Neva, connected to the spit of Vasilyevsky Island via the Palace Bridge, lie the Admiralty building, the vast Hermitage Museum complex stretching along the Palace Embankment, which includes the Baroque Winter Palace, former official residence of Russian emperors, as well as the neoclassical Marble Palace. The Winter Palace faces Palace Square, the city's main square with the Alexander Column.

Nevsky Prospekt, also on the left bank of the Neva, is the city's main avenue. It starts at the Admiralty and runs eastwards next to Palace Square. Nevsky Prospekt crosses the Moika (Green Bridge), Griboyedov Canal (Kazansky Bridge), Garden Street, the Fontanka (Anichkov Bridge), meets Liteyny Prospekt and proceeds to Uprising Square near the Moskovsky railway station, where it meets Ligovsky Prospekt and turns to the Alexander Nevsky Lavra. The Passage, Catholic Church of St. Catherine, Book House (former Singer Manufacturing Company Building in the Art Nouveau style), Grand Hotel Europe, Lutheran Church of Saint Peter and Saint Paul, Great Gostiny Dvor, Russian National Library, Alexandrine Theatre behind Mikeshin's statue of Catherine the Great, Kazan Cathedral, Stroganov Palace, Anichkov Palace and Beloselsky-Belozersky Palace are all along that avenue.

The Alexander Nevsky Lavra, intended to house the relics of St. Alexander Nevsky, is an important centre of Christian education in Russia. It also contains the Tikhvin Cemetery with graves of many notable Petersburgers.

On the territory between the Neva and Nevsky Prospekt, the Church of the Savior on Blood, Mikhailovsky Palace housing the Russian Museum, Field of Mars, St. Michael's Castle, Summer Garden, Tauride Palace, Smolny Institute and Smolny Convent are located.

Many notable landmarks are to the west and south of the Admiralty Building, including the Trinity Cathedral, Mariinsky Palace, Hotel Astoria, famous Mariinsky Theatre, New Holland Island, Saint Isaac's Cathedral, the largest in the city, and Senate Square, with the Bronze Horseman, 18th-century equestrian monument to Peter the Great, which is considered among the city's most recognisable symbols. Other symbols of Saint Petersburg include the weather vane in the shape of a small ship on top of the Admiralty's golden spire and the golden angel on top of the Peter and Paul Cathedral. The Palace Bridge drawn at night is yet another symbol of the city.

From April to November, 22 bridges across the Neva and main canals are drawn to let ships pass in and out of the Baltic Sea according to a schedule.[114] It was not until 2004 that the first high bridge across the Neva, which does not need to be drawn, Big Obukhovsky Bridge, was opened. The most remarkable bridges of our days are Korabelny and Petrovsky cable-stayed bridges, which form the most spectacular part of the city toll road, Western High-Speed Diameter. There are hundreds of smaller bridges in Saint Petersburg spanning numerous canals and distributaries of the Neva, some of the most important of which are the Moika, Fontanka, Griboyedov Canal, Obvodny Canal, Karpovka, and Smolenka. Due to the intricate web of canals, Saint Petersburg is often called Venice of the North. The rivers and canals in the city centre are lined with granite embankments. The embankments and bridges are separated from rivers and canals by granite or cast iron parapets.

Southern suburbs of the city feature former imperial residences, including Petergof, with majestic fountain cascades and parks, Tsarskoe Selo, with the baroque Catherine Palace and the neoclassical Alexander Palace, and Pavlovsk, which has a domed palace of Emperor Paul and one of Europe's largest English-style parks. Some other residences nearby and making part of the world heritage site, including a castle and park in Gatchina, actually belong to Leningrad Oblast rather than Saint Petersburg. Another notable suburb is Kronstadt with its 19th-century fortifications and naval monuments, occupying the Kotlin Island in the Gulf of Finland.

Since around the end of the 20th century, a great deal of active building and restoration works have been carried out in a number of the city's older districts. The authorities have recently been compelled to transfer the ownership of state-owned private residences in the city centre to private lessors. Many older buildings have been reconstructed to allow their use as apartments and penthouses.

Some of these structures, such as the Saint Petersburg Commodity and Stock Exchange have been recognised as town-planning errors.[115]

Parks

[edit]

Saint Petersburg is home to many parks and gardens. Some of the most well-known are in the southern suburbs, including Pavlovsk, one of Europe's largest English gardens. Sosnovka is the largest park within the city limits, occupying 240 ha. The Summer Garden is the oldest, dating back to the early 18th century and designed in the regular style. It is on the Neva's southern bank at the head of the Fontanka and is famous for its cast iron railing and marble sculptures.

Among other notable parks are the Maritime Victory Park on Krestovsky Island and the Moscow Victory Park in the south, both commemorating the victory over Nazi Germany in the Second World War, as well as the Central Park of Culture and Leisure occupying Yelagin Island and the Tauride Garden around the Tauride Palace. The most common trees grown in the parks are the English oak, Norway maple, green ash, silver birch, Siberian Larch, blue spruce, crack willow, limes, and poplars. Important dendrological collections dating back to the 19th century are hosted by the Saint Petersburg Botanical Garden and the Park of the Forestry Academy.

In order to commemorate 300 years anniversary of Saint Petersburg, a new park was laid out. The park is in the northwestern part of the city. The construction started in 1995. It is planned to connect the park with the pedestrian bridge to the territory of Lakhta Center's recreation areas. In the park 300 trees of valuable sorts, 300 decorative apple trees, and 70 limes. 300 other trees and bushes were planted. These trees were presented to Saint Petersburg by non-commercial and educational organizations of the city, its sister-cities, the city of Helsinki, heads of other regions of Russia, German Savings Bank and other people and organizations.[116]

-

Cameron gallery in Catherine park of Tsarskoe Selo

-

Grotto pavilion in Catherine park of Tsarskoe Selo

-

The Imperial Lyceum in Tsarskoye Selo

-

Grand Menshikov Palace

Tall structures

[edit]Regulations forbid the construction of tall buildings in Saint Petersburg's city centre. Until the early 2010s, three skyscrapers were built: Leader Tower (140 m), Alexander Nevsky (124 m), and Atlantic City (105 m) – all situated far from the historical centre. The 310-metre (1,020 ft) tall Saint Petersburg TV Tower, constructed in 1962, was the tallest structure in the city.

However, a controversial project endorsed by the city authorities was announced, known as the Okhta Center, to build a 396-metre (1,299 ft) supertall skyscraper. In 2008, the World Monuments Fund included the Saint Petersburg historic skyline on the watch list of the 100 most endangered sites due to the expected construction, which threatened to alter it drastically.[117] The Okhta Center project was cancelled at the end of 2010.

In 2012, the Lakhta Center project began in the city's outskirts, to include a 463-metre (1,519 ft) tall office skyscraper and several low-rise mixed-use buildings. The latter project caused much less controversy. Unlike the previous unbuilt project, it was not seen by UNESCO as a potential threat to the city's cultural heritage due to its remote location from the historic centre. The skyscraper was completed in 2019, and at 462.5 meters, it is currently the tallest in Russia and Europe.

Tourism

[edit]This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: Needs discussion on how the Russian invasion of Ukraine has affected tourism. (June 2023) |

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| |

| Official name | Historic Centre of Saint Petersburg and Related Groups of Monuments |

| Criteria | Cultural: (i), (ii), (iv), (vi) |

| Reference | 540bis |

| Inscription | 1990 (14th Session) |

| Extensions | 2013 |

| Area | 3,934.1 ha (15.190 sq mi) |

Saint Petersburg has a significant historical and cultural heritage.[118][119][120][121][122][123][124]

The city's 18th and 19th-century architectural ensemble and its environs are preserved in virtually unchanged form. For various reasons (including large-scale destruction during World War II and construction of modern buildings during the postwar period in the largest historical centres of Europe), Saint Petersburg has become a unique reserve of European architectural styles of the past three centuries. Saint Petersburg's loss of capital city status helped it retain many of its pre-revolutionary buildings, as modern architectural 'prestige projects' tended to be built in Moscow; this largely prevented the rise of mid-to-late-20th-century architecture and helped maintain the architectural appearance of the historic city centre.

Saint Petersburg is inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage list as an area with 36 historical architectural complexes and around 4000 outstanding individual monuments of architecture, history, and culture. New tourist programs and sightseeing tours have been developed for those wishing to see Saint Petersburg's cultural heritage.

The city has 221 museums, 2,000 libraries, more than 80 theatres, 100 concert organizations, 45 galleries and exhibition halls, 62 cinemas, and 80 other cultural establishments. Every year, the city hosts around 100 festivals and various competitions of art and culture, including more than 50 international ones.[citation needed]

Despite the economic instability of the 1990s, not a single major theatre or museum was closed in Saint Petersburg; on the contrary many new ones opened, for example a private museum of puppets (opened in 1999) is the third museum of its kind in Russia, where collections of more than 2000 dolls are presented including 'The multinational Saint Petersburg' and Pushkin's Petersburg. The museum world of Saint Petersburg is incredibly diverse. The city is not only home to the world-famous Hermitage Museum and the Russian Museum with its rich collection of Russian art, but also the palaces of Saint Petersburg and its suburbs, so-called small-town museums and others like the museum of famous Russian writer Dostoyevsky; Museum of Musical Instruments, the museum of decorative arts and the museum of professional orientation.

The musical life of Saint Petersburg is rich and diverse, with the city now playing host to a number of annual carnivals. Ballet performances occupy a special place in the cultural life of Saint Petersburg. The Petersburg School of Ballet is named as one of the best in the world. Traditions of the Russian classical school have been passed down from generation to generation among outstanding educators. The art of famous and prominent Saint Petersburg dancers like Rudolf Nureyev, Natalia Makarova, Mikhail Baryshnikov was, and is, admired throughout the world. Contemporary Petersburg ballet is made up not only of traditional Russian classical school but also ballets by those like Boris Eifman, who expanded the scope of strict classical Russian ballet to almost unimaginable limits. Remaining faithful to the classical basis (he was a choreographer at the Vaganova Academy of Russian Ballet), he combined classical ballet with the avant-garde style, and then, in turn, with acrobatics, rhythmic gymnastics, dramatic expressiveness, cinema, color, light, and finally with spoken word.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has impacted tourism. The British Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office advises against travelling to Russia, including Saint Petersburg, noting there have been reports of fires and explosions in areas close to the city.[125]

Media and communications

[edit]All major Russian newspapers are active in Saint Petersburg. The city has a developed telecommunications system. In 2014, Rostelecom, the national operator, announced the beginning of a major modernization of the fixed-line network in the city.[126]

Culture

[edit]Museums

[edit]Saint Petersburg is home to more than two hundred museums, many of them in historic buildings. The largest is the Hermitage Museum that features the interiors of the former imperial residence and a vast collection of art. The Russian Museum is a large museum devoted to Russian fine art. The apartments of some famous people, including Alexander Pushkin, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Feodor Chaliapin, Alexander Blok, Vladimir Nabokov, Anna Akhmatova, Mikhail Zoshchenko, Joseph Brodsky, as well as some palace and park ensembles of the southern suburbs and notable architectural monuments such as St. Isaac's Cathedral, have also been turned into public museums.

The Kunstkamera, with its collection established in 1714 by Peter the Great to collect curiosities from all over the world, is sometimes considered the first museum in Russia, which has evolved into the present-day Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography. The Russian Ethnography Museum, which has been split from the Russian Museum, is devoted to the cultures of the people of Russia, the former Soviet Union, and the Russian Empire.

-

The State Russian Museum is the world's largest depository of Russian fine art.

-

The Russian Museum of Ethnography is one of the largest ethnographic museums in the world.[128]

Several museums provide insight into the Soviet history of Saint Petersburg, including the Museum of the Blockade, which describes the Siege of Leningrad and the Museum of Political History, which explains many authoritarian features of the USSR.

Other notable museums include the Central Naval Museum, and Zoological Museum, Central Soil Museum, the Russian Railway Museum, Suvorov Museum, Museum of the Siege of Leningrad, Erarta Museum of Contemporary Art, the largest non-governmental museum of contemporary art in Russia, Saint Petersburg Museum of History in the Peter and Paul Fortress and Artillery Museum, which includes not only artillery items, but also a huge collection of other military equipment, uniforms, and decorations. Amongst others, Saint Petersburg also hosts the State Museum of the History of Religion, one of the oldest museums in Russia about religion, depicting cultural representations from various parts of the globe.[129]

Music

[edit]

Among the city's more than fifty theatres is the Mariinsky Theatre (formerly known as the Kirov Theatre), home to the Mariinsky Ballet company and opera. Leading ballet dancers, such as Vaslav Nijinsky, Anna Pavlova, Rudolf Nureyev, Mikhail Baryshnikov, Galina Ulanova and Natalia Makarova, were principal stars of the Mariinsky ballet.

The first music school, the Saint Petersburg Conservatory, was founded in 1862 by the Russian pianist and composer Anton Rubinstein. The school alumni have included such notable composers as Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Sergei Prokofiev, Artur Kapp, Rudolf Tobias, and Dmitri Shostakovich, who taught at the conservatory during the 1960s, bringing it additional fame. The renowned Russian composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov also taught at the conservatory from 1871 to 1905. Among his students were Igor Stravinsky, Alexander Glazounov, Anatoly Liadov and others. The former St. Petersburg apartment of Rimsky-Korsakov has been faithfully preserved as the composer's only museum.

Dmitri Shostakovich, who was born and raised in Saint Petersburg, dedicated his Seventh Symphony to the city, calling it the "Leningrad Symphony". He wrote the symphony while based in the city during the siege of Leningrad. It was premiered in Samara in March 1942; a few months later, it received its first performance in the besieged Leningrad at the Bolshoy Philharmonic Hall under the baton of conductor Karl Eliasberg. It was heard over the radio and was said to have lifted the spirits of the surviving population.[130] In 1992, the 7th Symphony was performed by the 14 surviving orchestral players of the Leningrad premiere in the same hall as half a century before.[131] The Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra remained one of the best known symphony orchestras in the world under the leadership of conductors Yevgeny Mravinsky and Yuri Temirkanov. Mravinsky's term as artistic director of the Leningrad Philharmonic – a term that is possibly the longest of any conductor with any orchestra in modern times – led the orchestra from a little-known provincial ensemble to one of the world's most highly regarded orchestras, especially for the performance of Russian music.

The Imperial Choral Capella was founded and modelled after the royal courts of other European capitals.

Saint Petersburg has been home to the newest movements in popular music in the country. The early Soviet jazz bands founded here included Leopold Teplitsky's First Concert Jazz Band (1927), Leonid Utyosov 's TheaJazz (1928, under the patronage of composer Isaak Dunayevsky), and Georgy Landsberg's Jazz Cappella (1929). The first jazz appreciation society in the Soviet Union was founded here in 1958 as J58, and later named jazz club Kvadrat. In 1956, the popular ensemble Druzhba was founded by Aleksandr Bronevitsky and Edita Piekha to become the first popular band in the USSR during the 1950s. In the 1960s, student rock-groups Argonavty, Kochevniki, and others pioneered a series of unofficial and underground rock concerts and festivals. In 1972, Boris Grebenshchikov founded the band Aquarium, which later grew to huge popularity. Since then, "Peter's rock" music style was formed.

In the 1970s many bands came out from the "underground" scene and eventually founded the Leningrad Rock Club, which provided a stage to bands such as DDT, Kino, Alisa, Zemlyane, Zoopark, Piknik, and Secret. The first Russian-style happening show Pop Mekhanika, mixing over 300 people and animals on stage, was directed by the multi-talented Sergey Kuryokhin in the 1980s. The Sergey Kuryokhin International Festival (SKIF) is named after him. In 2004, the Kuryokhin Center was founded, where the SKIF and the Electro-Mechanica and Ethnomechanica festivals take place. SKIF focuses on experimental pop music and avant-garde music, Electro-Mechanica on electronic music, and Ethnomechanica on world music.

Today's Saint Petersburg boasts many notable musicians of various genres, from popular Leningrad's Sergei Shnurov, Tequilajazzz, Splean, and Korol i Shut, to rock veterans Yuri Shevchuk, Vyacheslav Butusov, and Mikhail Boyarsky. In the early 2000s the city saw a wave of popularity of metalcore, rapcore, and emocore, and there are bands such as Amatory, Kirpichi, Psychea, Stigmata, Grenouer and Animal Jazz.

The White Nights Festival in Saint Petersburg is famous for spectacular fireworks and a massive show celebrating the end of the school year.

The rave band Little Big also hails from Saint Petersburg. Their music video for "Skibidi" was filmed in the city, starting at Akademicheskiy Pereulok.[132]

Literature

[edit]

Saint Petersburg has a longstanding and world-famous tradition in literature. Dostoyevsky called it "The most abstract and intentional city in the world", emphasizing its artificiality, but it was also a symbol of modern disorder in a changing Russia. It often appeared to Russian writers as a menacing and inhuman mechanism. The grotesque and often nightmarish image of the city is featured in Pushkin's last poems, the Petersburg stories of Gogol, the novels of Dostoyevsky, the verse of Alexander Blok and Osip Mandelshtam, and in the symbolist novel Petersburg by Andrey Bely. According to Lotman in his chapter, 'The Symbolism of Saint Petersburg' in Universe and the Mind, these writers were inspired by symbolism from within the city itself. The effect of life in Saint Petersburg on the plight of the poor clerk in a society obsessed with hierarchy and status also became an important theme for authors such as Pushkin, Gogol, and Dostoyevsky. Another important feature of early Saint Petersburg literature is its mythical element, which incorporates urban legends and popular ghost stories, as the stories of Pushkin and Gogol included ghosts returning to Saint Petersburg to haunt other characters as well as other fantastical elements, creating a surreal and abstract image of Saint Petersburg.

Twentieth-century writers from Saint Petersburg, such as Vladimir Nabokov, Ayn Rand, Andrey Bely and Yevgeny Zamyatin, along with his apprentices, The Serapion Brothers, created entirely new styles in literature and contributed new insights to the understanding of society through their experience in this city. Anna Akhmatova became an important leader for Russian poetry. Her poem Requiem adumbrates the perils encountered during the Stalinist era. Another notable 20th-century writer from Saint Petersburg is Joseph Brodsky, recipient of the Nobel Prize in Literature (1987). While living in the United States, his writings in English reflected on life in Saint Petersburg from the unique perspective of being both an insider and an outsider to the city in essays such as "A Guide to a Renamed City" and the nostalgic "In a Room and a Half".[133]

Film

[edit]

Over 300 international and Russian movies were filmed in Saint Petersburg.[134] Well over a thousand feature films about tsars, revolution, people and stories set in Saint Petersburg have been produced worldwide but not filmed in the city. The first film studios were founded in Saint Petersburg in the 20th century, and since the 1920s, Lenfilm has been the largest film studio based in Saint Petersburg. The first foreign feature movie filmed entirely in Saint Petersburg was the 1997 production of Tolstoy's Anna Karenina, starring Sophie Marceau and Sean Bean and made by an international team of British, American, French, and Russian filmmakers.

The cult comedy Irony of Fate[135] (also Ирония судьбы, или С лёгким паром!) is set in Saint Petersburg and pokes fun at Soviet city planning. The 1985 film White Nights received considerable Western attention for having captured genuine Leningrad street scenes at a time when filming in the Soviet Union by Western production companies was generally unheard of. Other movies include GoldenEye (1995), Midnight in Saint Petersburg (1996), Brother (1997) and Tamil romantic thriller film-Dhaam Dhoom (2008). Onegin (1999) is based on the Pushkin poem and showcases many tourist attractions. In addition, the Russian romantic comedy, Piter FM, intricately showcases the cityscape, almost as if it were a main character in the film.

Several international film festivals are held annually, such as the Festival of Festivals, Saint Petersburg, as well as the Message to Man International Documentary Film Festival, since its inauguration in 1988 during the White Nights.[136]

Dramatic theatre

[edit]Saint Petersburg has more than a hundred theatres and theatre companies.[137]

Education

[edit]As of 2006[update]–2007, there were 1,024 kindergartens, 716 public schools and 80 vocational schools in Saint Petersburg.[138] The largest of the public higher education institutions is Saint Petersburg State University, enrolling approximately 32,000 undergraduate students;[139] and the largest non-governmental higher education institutions is the Institute of International Economic Relations, Economics, and Law. Other famous universities are Saint Petersburg Polytechnic University, Herzen University, Saint Petersburg State University of Economics and Finance, Saint Petersburg State University of Architecture and Civil Engineering, and Saint Petersburg Military engineering-technical university. However, the public universities are all federal property and do not belong to the city.

Sports

[edit]

Leningrad hosted part of the association football tournament during the 1980 Summer Olympics. The 1994 Goodwill Games were also held here.[140]

In boating, the first competition here was the 1703 rowing event initiated by Peter the Great, after the victory over the Swedish fleet. The Russian Navy has held Yachting events since the foundation of the city. Yacht clubs:[141] St. Petersburg River Yacht Club, Neva Yacht Club, the latter is the oldest yacht club in the world. In the winter, when the sea and lake surfaces are frozen and yachts and dinghies cannot be used, local people sail ice boats.

Equestrianism has been a long tradition, popular among the Tsars and aristocracy, as well as part of military training. Several historic sports arenas were built for equestrianism since the 18th century to maintain training all year round, such as the Zimny Stadion and Konnogvardeisky Manezh.

Chess tradition was highlighted by the 1914 international tournament, partially funded by the Tsar, in which the title "Grandmaster" was first formally conferred by Russian Tsar Nicholas II to five players: Lasker, Capablanca, Alekhine, Tarrasch and Marshall.

The city's main football team is FC Zenit Saint Petersburg, who have been champions of the Soviet and Russian league nine times, most notably claiming the RPL title in four consecutive seasons from 2018–19 to 2021–22, along with winning the Soviet/Russian Cup five times. The club also won the 2007–08 UEFA Cup and the 2008 UEFA Super Cup, spearheaded by successful player and local hero Andrey Arshavin.

Kirov Stadium formerly existed as Zenit's home from 1950 to 1993 and again in 1995, being one of the largest stadiums in the world at the time. In 1951, a crowd of 110,000 set the single-game attendance record for Soviet football. The stadium was knocked down in 2006, with Zenit temporarily moving to the Petrovsky Stadium before the Krestovsky Stadium was built on the same site as the Kirov Stadium. The Krestovsky Stadium opened in 2017, hosting four matches at the 2017 FIFA Confederations Cup, including the final. The stadium then hosted seven matches at the 2018 FIFA World Cup, including a semi-final and the third-placed playoff. It also hosted seven matches at UEFA Euro 2020, including a quarter-final. The stadium was going to host the 2022 UEFA Champions League final, however UEFA removed Saint Petersburg as host in February 2022, citing the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.[142]

Hockey teams in the city include SKA Saint Petersburg in the KHL, HC VMF Saint Petersburg in the VHL, and junior clubs SKA-1946 and Silver Lions in the Russian Major League. SKA Saint Petersburg is one of the most popular in the KHL, consistently being at or near the top of the league in attendance. Along with their popularity, they are one of the best teams in the KHL right now, as they have won the Gagarin Cup twice.[143] Well-known players on the team include Pavel Datsyuk, Ilya Kovalchuk, Nikita Gusev, Sergei Shirokov and Viktor Tikhonov. During the NHL lockout, stars Ilya Kovalchuk, Sergei Bobrovsky, and Vladimir Tarasenko also played for the team. They play their home games at SKA Arena.

The city's long-time basketball team is BC Spartak Saint Petersburg, which launched the career of Andrei Kirilenko. BC Spartak Saint Petersburg won two championships in the USSR Premier League (1975 and 1992), two USSR Cups (1978 and 1987), and a Russian Cup title (2011). They also won the Saporta Cup twice (1973 and 1975). Legends of the club include Alexander Belov and Vladimir Kondrashin. BC Zenit Saint Petersburg also play in the city, being formed in 2014.

Transportation

[edit]

Saint Petersburg is a major transport hub. The first Russian railway was built here in 1837, and since then, the city's transport infrastructure has kept pace with the city's growth. Petersburg has an extensive system of local roads and railway services, maintains a large public transport system that includes the Saint Petersburg tram and the Saint Petersburg Metro, and is home to several riverine services that convey passengers around the city efficiently and in relative comfort.

The city is connected to the rest of Russia and the wider world by several federal highways and national and international rail routes. Pulkovo Airport serves most of the air passengers departing from or arriving in the city.

Public transport

[edit]

Saint Petersburg has an extensive city-funded network of public transport including buses, trams, and trolleybuses.

In the 1980s, the city had the largest tram network globally.[144][145] However, like in many Russian cities, trams were dismantled after the dissolution of the Soviet Union.[146]

Buses carry up to 3 million passengers daily, with over 250 urban and suburban bus routes.

Saint Petersburg Metro was opened in 1955; it now has 5 lines with 73 stations, connecting all five railway terminals,[147] and carrying 2.3 million passengers daily. Many stations are elaborately decorated with materials such as marble and bronze. There are plans for extending several lines and building one new depot.[148] Plans call for 16 new stations to open between 2025 and 2035, including 10 that will open between 2025 and 2030.[149] The Admiralteysko-Okhtinskaya and Koltsevaya line is projected to open after the 2030s.[150]

| Saint Petersburg Metro map |

|---|

|

Roads

[edit]Traffic jams are common in the city due to daily commuter traffic volumes, intercity traffic, and excessive winter snow. The construction of freeways such as the Saint Petersburg Ring Road, completed in 2011, and the Western High-Speed Diameter, completed in 2017, helped reduce traffic in the city. The M11 Neva, also known as the Moscow-Saint Petersburg Motorway, is a federal highway, and connects Saint Petersburg to Moscow by a freeway.

Saint Petersburg is an important transport corridor linking Scandinavia to Russia and Eastern Europe. The city is a node of the international European routes E18 towards Helsinki, E20 towards Tallinn, E95 towards Pskov, Kyiv and Odesa and E105 towards Petrozavodsk, Murmansk and Kirkenes (north) and towards Moscow and Kharkiv (south).

Waterways

[edit]