Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

MATLAB

View on Wikipedia

| MATLAB (software) | |

|---|---|

L-shaped membrane logo[1] | |

| Developer | MathWorks |

| Initial release | 1984 |

| Stable release | R2025b[2] |

| Written in | C/C++, MATLAB |

| Operating system | Windows, macOS, and Linux[3][4] |

| Platform | IA-32, x86-64, ARM64 |

| Type | Numerical computing |

| License | Proprietary commercial software |

| Website | mathworks.com |

| MATLAB (programming language) | |

|---|---|

| Paradigm | multi-paradigm: functional, imperative, procedural, object-oriented, array |

| Designed by | Cleve Moler |

| Developer | MathWorks |

| First appeared | late 1970s |

| Stable release | R2025b[2] |

| Typing discipline | dynamic, weak |

| Filename extensions | .m, .p,[5] .mex*,[6] .mat,[7] .fig,[8] .mlx,[9] .mlapp,[10] .mltbx,[11] .mlappinstall,[12] .mlpkginstall[13] |

| Website | mathworks.com |

| Influenced by | |

| Influenced | |

| |

MATLAB (Matrix Laboratory)[18] is a proprietary multi-paradigm programming language and numeric computing environment developed by MathWorks. MATLAB allows matrix manipulations, plotting of functions and data, implementation of algorithms, creation of user interfaces, and interfacing with programs written in other languages.

Although MATLAB is intended primarily for numeric computing, an optional toolbox uses the MuPAD symbolic engine allowing access to symbolic computing abilities. An additional package, Simulink, adds graphical multi-domain simulation and model-based design for dynamic and embedded systems.

As of 2020[update], MATLAB has more than four million users worldwide.[19] They come from various backgrounds of engineering, science, and economics. As of 2017[update], more than 5000 global colleges and universities use MATLAB to support instruction and research.[20]

History

[edit]Origins

[edit]MATLAB was invented by mathematician and computer programmer Cleve Moler.[21] The idea for MATLAB was based on his 1960s PhD thesis.[21] Moler became a math professor at the University of New Mexico and started developing MATLAB for his students[21] as a hobby.[22] He developed MATLAB's initial linear algebra programming in 1967 with his one-time thesis advisor, George Forsythe.[21] This was followed by Fortran code for linear equations in 1971.[21]

Before version 1.0, MATLAB "was not a programming language; it was a simple interactive matrix calculator. There were no programs, no toolboxes, no graphics. And no ODEs or FFTs."[23]

The first early version of MATLAB was completed in the late 1970s.[21] The software was disclosed to the public for the first time in February 1979 at the Naval Postgraduate School in California.[22] Early versions of MATLAB were simple matrix calculators with 71 pre-built functions.[24] At the time, MATLAB was distributed for free[25][26] to universities.[27] Moler would leave copies at universities he visited and the software developed a strong following in the math departments of university campuses.[28]: 5

In the 1980s, Cleve Moler met John N. Little. They decided to reprogram MATLAB in C and market it for the IBM desktops that were replacing mainframe computers at the time.[21] John Little and programmer Steve Bangert re-programmed MATLAB in C, created the MATLAB programming language, and developed features for toolboxes.[22]

Commercial development

[edit]MATLAB was first released as a commercial product in 1984 at the Automatic Control Conference in Las Vegas.[21][22] MathWorks, Inc. was founded to develop the software[26] and the MATLAB programming language was released.[24] The first MATLAB sale was the following year, when Nick Trefethen from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology bought ten copies.[22][29]

By the end of the 1980s, several hundred copies of MATLAB had been sold to universities for student use.[22] The software was popularized largely thanks to toolboxes created by experts in various fields for performing specialized mathematical tasks.[25] Many of the toolboxes were developed as a result of Stanford students that used MATLAB in academia, then brought the software with them to the private sector.[22]

Over time, MATLAB was re-written for early operating systems created by Digital Equipment Corporation, VAX, Sun Microsystems, and for Unix PCs.[22][24] Version 3 was released in 1987.[30] The first MATLAB compiler was developed by Stephen C. Johnson in the 1990s.[24]

In 2000, MathWorks added a Fortran-based library for linear algebra in MATLAB 6, replacing the software's original LINPACK and EISPACK subroutines that were in C.[24] MATLAB's Parallel Computing Toolbox was released at the 2004 Supercomputing Conference and support for graphics processing units (GPUs) was added to it in 2010.[24]

Recent history

[edit]Some especially large changes to the software were made with version 8 in 2012.[31] The user interface was reworked[citation needed] and Simulink's functionality was expanded.[32]

By 2016, MATLAB had introduced several technical and user interface improvements, including the MATLAB Live Editor notebook, and other features.[24]

Release history

[edit]For a complete list of changes of both MATLAB an official toolboxes, check MATLAB previous releases.[33]

| Name of release | MATLAB | Simulink, Stateflow (MATLAB attachments) | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Volume 8 | 5.0 | 1996 | |

| Volume 9 | 5.1 | 1997 | |

| R9.1 | 5.1.1 | 1997 | |

| R10 | 5.2 | 1998 | |

| R10.1 | 5.2.1 | 1998 | |

| R11 | 5.3 | 1999 | |

| R11.1 | 5.3.1 | 1999 | |

| R12 | 6.0 | 2000 | |

| R12.1 | 6.1 | 2001 | |

| R13 | 6.5 | 2002 | |

| R13SP1 | 6.5.1 | 2003 | |

| R13SP2 | 6.5.2 | ||

| R14 | 7 | 6.0 | 2004 |

| R14SP1 | 7.0.1 | 6.1 | |

| R14SP2 | 7.0.4 | 6.2 | 2005 |

| R14SP3 | 7.1 | 6.3 | |

| R2006a | 7.2 | 6.4 | 2006 |

| R2006b | 7.3 | 6.5 | |

| R2007a | 7.4 | 6.6 | 2007 |

| R2007b | 7.5 | 7.0 | |

| R2008a | 7.6 | 7.1 | 2008 |

| R2008b | 7.7 | 7.2 | |

| R2009a | 7.8 | 7.3 | 2009 |

| R2009b | 7.9 | 7.4 | |

| R2010a | 7.10 | 7.5 | 2010 |

| R2010b | 7.11 | 7.6 | |

| R2011a | 7.12 | 7.7 | 2011 |

| R2011b | 7.13 | 7.8 | |

| R2012a | 7.14 | 7.9 | 2012 |

| R2012b | 8.0 | 8.0 | |

| R2013a | 8.1 | 8.1 | 2013 |

| R2013b | 8.2 | 8.2 | |

| R2014a | 8.3 | 8.3 | 2014 |

| R2014b | 8.4 | 8.4 | |

| R2015a | 8.5 | 8.5 | 2015 |

| R2015b | 8.6 | 8.6 | |

| R2016a | 9.0 | 8.7 | 2016 |

| R2016b | 9.1 | 8.8 | |

| R2017a | 9.2 | 8.9 | 2017 |

| R2017b | 9.3 | 9.0 | |

| R2018a | 9.4 | 9.1 | 2018 |

| R2018b | 9.5 | 9.2 | |

| R2019a | 9.6 | 9.3 | 2019 |

| R2019b | 9.7 | 10.0 | |

| R2020a | 9.8 | 10.1 | 2020 |

| R2020b | 9.9 | 10.2 | |

| R2021a | 9.10 | 10.3 | 2021 |

| R2021b | 9.11 | 10.4 | |

| R2022a | 9.12 | 10.5 | 2022 |

| R2022b | 9.13 | 10.6 | |

| R2023a | 9.14 | 10.7 | 2023 |

| R2023b | 23.2 | 23.2 | |

| R2024a | 24.1 | 24.1 | 2024 |

| R2024b | 24.2 | 24.2 | |

| R2025a | 25.1 | 25.1 | 2025 |

| R2025b | 25.2 | 25.2 | |

Syntax

[edit]The MATLAB application is built around the MATLAB programming language.

Common usage of the MATLAB application involves using the "Command Window" as an interactive mathematical shell or executing text files containing MATLAB code.[34]

"Hello, world!" example

[edit]An example of a "Hello, world!" program exists in MATLAB.

disp('Hello, world!')

It displays like so:

Hello, world!

Variables

[edit]Variables are defined using the assignment operator, =.

MATLAB is a weakly typed programming language because types are implicitly converted.[35] It is an inferred typed language because variables can be assigned without declaring their type, except if they are to be treated as symbolic objects,[36] and that their type can change.

Values can come from constants, from computation involving values of other variables, or from the output of a function.

For example:

>> x = 17

x =

17

>> x = 'hat'

x =

hat

>> x = [3*4, pi/2]

x =

12.0000 1.5708

>> y = 3*sin(x)

y =

-1.6097 3.0000

Vectors and matrices

[edit]A simple array is defined using the colon syntax: initial:increment:terminator. For instance:

>> array = 1:2:9

array =

1 3 5 7 9

defines a variable named array (or assigns a new value to an existing variable with the name array) which is an array consisting of the values 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9. That is, the array starts at 1 (the initial value), increments with each step from the previous value by 2 (the increment value), and stops once it reaches (or is about to exceed) 9 (the terminator value).

The increment value can actually be left out of this syntax (along with one of the colons), to use a default value of 1.

>> ari = 1:5

ari =

1 2 3 4 5

assigns to the variable named ari an array with the values 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, since the default value of 1 is used as the increment.

Indexing is one-based,[37] which is the usual convention for matrices in mathematics, unlike zero-based indexing commonly used in other programming languages such as C, C++, and Java.

Matrices can be defined by separating the elements of a row with blank space or comma and using a semicolon to separate the rows. The list of elements should be surrounded by square brackets []. Parentheses () are used to access elements and subarrays (they are also used to denote a function argument list).

>> A = [16, 3, 2, 13 ; 5, 10, 11, 8 ; 9, 6, 7, 12 ; 4, 15, 14, 1]

A =

16 3 2 13

5 10 11 8

9 6 7 12

4 15 14 1

>> A(2,3)

ans =

11

Sets of indices can be specified by expressions such as 2:4, which evaluates to [2, 3, 4]. For example, a submatrix taken from rows 2 through 4 and columns 3 through 4 can be written as:

>> A(2:4,3:4)

ans =

11 8

7 12

14 1

A square identity matrix of size n can be generated using the function eye, and matrices of any size with zeros or ones can be generated with the functions zeros and ones, respectively.

>> eye(3,3)

ans =

1 0 0

0 1 0

0 0 1

>> zeros(2,3)

ans =

0 0 0

0 0 0

>> ones(2,3)

ans =

1 1 1

1 1 1

Transposing a vector or a matrix is done either by the function transpose or by adding dot-prime after the matrix (without the dot, prime will perform conjugate transpose for complex arrays):

>> A = [1 ; 2], B = A.', C = transpose(A)

A =

1

2

B =

1 2

C =

1 2

>> D = [0, 3 ; 1, 5], D.'

D =

0 3

1 5

ans =

0 1

3 5

Most functions accept arrays as input and operate element-wise on each element. For example, mod(2*J,n) will multiply every element in J by 2, and then reduce each element modulo n. MATLAB does include standard for and while loops, but (as in other similar applications such as APL and R), using the vectorized notation is encouraged and is often faster to execute. The following code, excerpted from the function magic.m, creates a magic square M for odd values of n (MATLAB function meshgrid is used here to generate square matrices I and J containing ):

[J,I] = meshgrid(1:n);

A = mod(I + J - (n + 3) / 2, n);

B = mod(I + 2 * J - 2, n);

M = n * A + B + 1;

Structures

[edit]MATLAB supports structure data types.[38] Since all variables in MATLAB are arrays, a more adequate name is "structure array", where each element of the array has the same field names. In addition, MATLAB supports dynamic field names[39] (field look-ups by name, field manipulations, etc.).

Functions

[edit]When creating a MATLAB function, the name of the file should match the name of the first function in the file. Valid function names begin with an alphabetic character, and can contain letters, numbers, or underscores. Variables and functions are case sensitive.[40]

rgbImage = imread('ecg.png');

grayImage = rgb2gray(rgbImage); % for non-indexed images

level = graythresh(grayImage); % threshold for converting image to binary,

binaryImage = im2bw(grayImage, level);

% Extract the individual red, green, and blue color channels.

redChannel = rgbImage(:, :, 1);

greenChannel = rgbImage(:, :, 2);

blueChannel = rgbImage(:, :, 3);

% Make the black parts pure red.

redChannel(~binaryImage) = 255;

greenChannel(~binaryImage) = 0;

blueChannel(~binaryImage) = 0;

% Now recombine to form the output image.

rgbImageOut = cat(3, redChannel, greenChannel, blueChannel);

imshow(rgbImageOut);

Function handles

[edit]MATLAB supports elements of lambda calculus by introducing function handles,[41] or function references, which are implemented either in .m files or anonymous[42]/nested functions.[43]

Classes and object-oriented programming

[edit]MATLAB supports object-oriented programming including classes, inheritance, virtual dispatch, packages, pass-by-value semantics, and pass-by-reference semantics.[44] However, the syntax and calling conventions are significantly different from other languages. MATLAB has value classes and reference classes, depending on whether the class has handle as a super-class (for reference classes) or not (for value classes).[45]

Method call behavior is different between value and reference classes. For example, a call to a method:

object.method();

can alter any member of object only if object is an instance of a reference class, otherwise value class methods must return a new instance if it needs to modify the object.

An example of a simple class is provided below:

classdef Hello

methods

function greet(obj)

disp('Hello!')

end

end

end

When put into a file named hello.m, this can be executed with the following commands:

>> x = Hello();

>> x.greet();

Hello!

Graphics and graphical user interface programming

[edit]This graph was using the legacy Graph extension, which is no longer supported. It needs to be converted to the new Chart extension. |

MATLAB has tightly integrated graph-plotting features. For example, the function plot can be used to produce a graph from two vectors x and y. The code:

x = 0:pi/100:2*pi;

y = sin(x);

plot(x,y)

produces the following figure of the sine function:

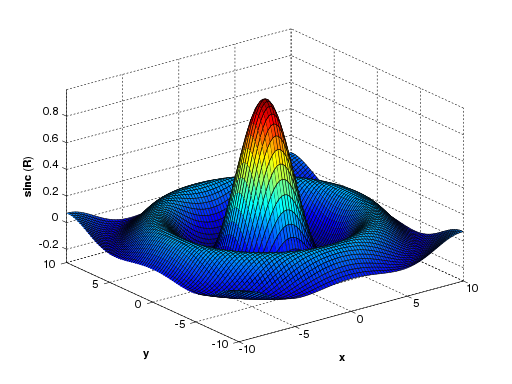

MATLAB supports three-dimensional graphics as well:

[X,Y] = meshgrid(-10:0.25:10,-10:0.25:10);

f = sinc(sqrt((X/pi).^2+(Y/pi).^2));

mesh(X,Y,f);

axis([-10 10 -10 10 -0.3 1])

xlabel('{\bfx}')

ylabel('{\bfy}')

zlabel('{\bfsinc} ({\bfR})')

hidden off

|

[X,Y] = meshgrid(-10:0.25:10,-10:0.25:10);

f = sinc(sqrt((X/pi).^2+(Y/pi).^2));

surf(X,Y,f);

axis([-10 10 -10 10 -0.3 1])

xlabel('{\bfx}')

ylabel('{\bfy}')

zlabel('{\bfsinc} ({\bfR})')

| |

| This code produces a wireframe 3D plot of the two-dimensional unnormalized sinc function: | This code produces a surface 3D plot of the two-dimensional unnormalized sinc function: | |

|

|

MATLAB supports developing graphical user interface (GUI) applications.[46] UIs can be generated either programmatically or using visual design environments such as GUIDE and App Designer.[47][48]

MATLAB and other languages

[edit]MATLAB can call functions and subroutines written in the programming languages C or Fortran.[49] A wrapper function is created allowing MATLAB data types to be passed and returned. MEX files (MATLAB executables) are the dynamically loadable object files created by compiling such functions.[50][51] Since 2014 increasing two-way interfacing with Python was being added.[52][53]

Libraries written in Perl, Java, ActiveX or .NET can be directly called from MATLAB,[54][55] and many MATLAB libraries (for example XML or SQL support) are implemented as wrappers around Java or ActiveX libraries. Calling MATLAB from Java is more complicated, but can be done with a MATLAB toolbox[56] which is sold separately by MathWorks, or using an undocumented mechanism called JMI (Java-to-MATLAB Interface),[57][58] (which should not be confused with the unrelated Java Metadata Interface that is also called JMI). Official MATLAB API for Java was added in 2016.[59]

As alternatives to the MuPAD based Symbolic Math Toolbox available from MathWorks, MATLAB can be connected to Maple or Mathematica.[60][61]

Relations to US sanctions

[edit]In 2020, MATLAB withdrew services from two Chinese universities as a result of US sanctions. The universities said this will be responded to by increased use of open-source alternatives and by developing domestic alternatives.[63]

See also

[edit]External Links

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "The L-Shaped Membrane". MathWorks. 2003. Archived from the original on April 23, 2019. Retrieved February 7, 2014.

- ^ a b https://www.mathworks.com/videos/r2025b-release-highlights-1757449057407.html.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "System Requirements and Platform Availability". MathWorks. Archived from the original on October 13, 2016. Retrieved August 14, 2013.

- ^ "Platform Road Map for MATLAB and Simulink Product Families". de.mathworks.com. Retrieved December 22, 2021.

- ^ "Protect Your Source Code". MathWorks. Retrieved November 1, 2019.

- ^ "MEX Platform Compatibility". MathWorks. Retrieved November 1, 2019.

- ^ "MAT-File Versions". MathWorks. Retrieved November 1, 2019.

- ^ "Save Figure to Reopen in MATLAB Later". MathWorks. Retrieved November 1, 2019.

- ^ "Live Code File Format (.mlx)". MathWorks. Retrieved November 1, 2019.

- ^ "MATLAB App Designer". MathWorks. Retrieved November 1, 2019.

- ^ "Toolbox Distribution". MathWorks. Retrieved November 1, 2019.

- ^ "MATLAB App Installer File". MathWorks. Archived from the original on January 17, 2014. Retrieved November 1, 2019.

- ^ "Support Package Installation". MathWorks. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved November 1, 2019.

- ^ "An interview with CLEVE MOLER Conducted by Thomas Haigh On 8 and 9 March, 2004 Santa Barbara, California" (PDF). Computer History Museum. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 27, 2014. Retrieved December 6, 2016.

So APL, Speakeasy, LINPACK, EISPACK, and PL0 were the predecessors to MATLAB.

- ^ Bezanson, Jeff; Karpinski, Stefan; Shah, Viral; Edelman, Alan (February 14, 2012). "Why We Created Julia". Julia Language. Retrieved December 1, 2016.

- ^ Eaton, John W. (May 21, 2001). "Octave: Past, Present, and Future" (PDF). Texas-Wisconsin Modeling and Control Consortium. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 9, 2017. Retrieved December 1, 2016.

- ^ "History". Scilab. Archived from the original on December 1, 2016. Retrieved December 1, 2016.

- ^ "Matrices and Arrays - MATLAB & Simulink". www.mathworks.com. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- ^ The MathWorks (February 2020). "Company Overview" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 19, 2020. Retrieved May 11, 2020.

- ^ "Current number of matlab users worldwide". Mathworks. November 9, 2017. Retrieved April 26, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Chonacky, N.; Winch, D. (2005). "Reviews of Maple, Mathematica, and Matlab: Coming Soon to a Publication Near You". Computing in Science & Engineering. 7 (2). Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE): 9–10. Bibcode:2005CSE.....7b...9C. doi:10.1109/mcse.2005.39. ISSN 1521-9615. S2CID 29660034.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Haigh, Thomas. "Cleve Moler: Mathematical Software Pioneer and Creator of Matlab" (PDF). IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. IEEE Computer Society.

- ^ "A Brief History of MATLAB". www.mathworks.com. Retrieved September 4, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Moler, Cleve; Little, Jack (June 12, 2020). "A history of MATLAB". Proceedings of the ACM on Programming Languages. 4 (HOPL). Association for Computing Machinery (ACM): 1–67. doi:10.1145/3386331. ISSN 2475-1421.

- ^ a b Xue, D.; Press, T.U. (2020). MATLAB Programming: Mathematical Problem Solutions. De Gruyter STEM. De Gruyter. p. 21. ISBN 978-3-11-066370-9. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ a b Press, CRC (2008). Solving Applied Mathematical Problems with MATLAB. CRC Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-4200-8251-7. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ Woodford, C.; Phillips, C. (2011). Numerical Methods with Worked Examples: Matlab Edition. SpringerLink : Bücher. Springer Netherlands. p. 1. ISBN 978-94-007-1366-6. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ Tranquillo, J.V. (2011). MATLAB for Engineering and the Life Sciences. Synthesis digital library of engineering and computer science. Morgan & Claypool Publishers. ISBN 978-1-60845-710-6. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ LoTurco, Lori (January 28, 2020). "Accelerating the pace of engineering". MIT News. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ Gatto, Marino; Rizzoli, Andrea (1993). "Review of MATLAB, Version 4.0". Natural Resource Modeling. 7 (1). Wiley: 85–88. Bibcode:1993NRM.....7...85G. doi:10.1111/j.1939-7445.1993.tb00141.x. ISSN 0890-8575.

- ^ Cho, M.J.; Martinez, W.L. (2014). Statistics in MATLAB: A Primer. Chapman & Hall/CRC Computer Science & Data Analysis. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4665-9657-3. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ Xue, D.; Chen, Y. (2013). System Simulation Techniques with MATLAB and Simulink. No Longer used. Wiley. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-118-69437-4. Retrieved October 15, 2020.

- ^ "MATLAB Previous releases". MathWorks. Retrieved December 3, 2024.

- ^ "MATLAB Documentation". MathWorks. Archived from the original on June 19, 2024. Retrieved August 14, 2013.

- ^ "Comparing MATLAB with Other OO Languages". MATLAB. MathWorks. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved August 14, 2013.

- ^ "Create Symbolic Variables and Expressions". Symbolic Math Toolbox. MathWorks. Archived from the original on July 12, 2013. Retrieved August 14, 2013.

- ^ "Matrix Indexing". MathWorks. Archived from the original on August 9, 2018. Retrieved August 14, 2013.

- ^ "Structures". MathWorks. Archived from the original on July 13, 2019. Retrieved August 14, 2013.

- ^ "Generate Field Names from Variables". MathWorks. Archived from the original on December 5, 2019. Retrieved August 14, 2013.

- ^ "Case and Space Sensitivity". MathWorks. Retrieved November 1, 2019.

- ^ "Function Handles". MathWorks. Archived from the original on July 19, 2020. Retrieved August 14, 2013.

- ^ "Anonymous Functions". MathWorks. Retrieved August 14, 2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Nested Functions". MathWorks. Archived from the original on July 19, 2020. Retrieved August 14, 2013.

- ^ "Object-Oriented Programming". MathWorks. Archived from the original on December 5, 2019. Retrieved August 14, 2013.

- ^ "Comparing Handle and Value Classes". MathWorks. Archived from the original on December 5, 2019. Retrieved August 14, 2013.

- ^ "MATLAB GUI". MathWorks. April 30, 2011. Archived from the original on January 17, 2022. Retrieved August 14, 2013.

- ^ "Create a Simple GUIDE GUI". MathWorks. Archived from the original on October 5, 2014. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

- ^ "MATLAB App Designer". MathWorks. Retrieved November 1, 2019.

- ^ "Application Programming Interfaces to MATLAB". MathWorks. Archived from the original on September 15, 2017. Retrieved August 14, 2013.

- ^ "Create MEX-Files". MathWorks. Archived from the original on March 3, 2014. Retrieved August 14, 2013.

- ^ Spielman, Dan (February 10, 2004). "Connecting C and Matlab". Yale University, Computer Science Department. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- ^ "MATLAB Engine for Python". MathWorks. Retrieved June 13, 2015.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Call Python Libraries". MathWorks. Archived from the original on December 5, 2019. Retrieved June 13, 2015.

- ^ "External Programming Language Interfaces". MathWorks. Archived from the original on March 11, 2014. Retrieved August 14, 2013.

- ^ "Call Perl script using appropriate operating system executable". MathWorks. Archived from the original on December 5, 2019. Retrieved November 7, 2013.

- ^ "MATLAB Builder JA". MathWorks. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2010.

- ^ Altman, Yair (April 14, 2010). "Java-to-Matlab Interface". Undocumented Matlab. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved June 7, 2010.

- ^ Kaplan, Joshua. "matlabcontrol JMI".

- ^ "MATLAB Engine API for Java". MathWorks. Archived from the original on September 19, 2020. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- ^ Germundsson, Roger (September 30, 1998). "MaMa: Calling MATLAB from Mathematica with MathLink". Wolfram Research. Wolfram Library Archive.

- ^ rsmenon; szhorvat (2013). "MATLink: Communicate with MATLAB from Mathematica". Retrieved August 14, 2013.

- ^ Weitzel, Michael (September 1, 2006). "MathML import/export". MathWorks - File Exchange. Archived from the original on February 25, 2011. Retrieved August 14, 2013.

- ^ "US military ban locks two Chinese universities out of popular software". South China Morning Post. June 12, 2020. Retrieved November 6, 2020.

Further reading

[edit]- Gilat, Amos (2004). MATLAB: An Introduction with Applications 2nd Edition. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-69420-5.

- Quarteroni, Alfio; Saleri, Fausto (2006). Scientific Computing with MATLAB and Octave. Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-32612-0.

- Ferreira, A.J.M. (2009). MATLAB Codes for Finite Element Analysis. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4020-9199-5.

- Lynch, Stephen (2004). Dynamical Systems with Applications using MATLAB. Birkhäuser. ISBN 978-0-8176-4321-8.

External links

[edit]MATLAB

View on GrokipediaHistory

Origins and Academic Roots

MATLAB originated in the late 1970s as an academic tool developed by Cleve Moler, a professor of mathematics and computer science at the University of New Mexico, to facilitate matrix computations for teaching and research in numerical linear algebra.[3] Moler, who had contributed to the development of the EISPACK library (released in versions from 1971 to 1976 for eigenvalue computations) and LINPACK (a 1975 package for solving linear systems), sought to make these Fortran-based routines accessible to students without requiring them to master Fortran programming or rely on costly mainframe computers from vendors such as DEC or IBM.[1][3] The initial version of MATLAB, implemented entirely in Fortran, functioned as a simple interactive matrix calculator that wrapped approximately a dozen subroutines from LINPACK and EISPACK, enabling users to perform operations like matrix multiplication, inversion, and eigenvalue decomposition through straightforward commands.[3] This design emphasized practical utility for engineering and scientific problem-solving, allowing direct experimentation with core algorithms of numerical analysis—such as QR decomposition and singular value decomposition—rooted in established mathematical methods rather than abstract theoretical constructs.[1] By encapsulating complex Fortran calls behind an intuitive interface, MATLAB addressed the empirical need for hands-on access to these tools on more affordable computing platforms available in academic settings during the era.[3] Moler first demonstrated MATLAB publicly in February 1979 during a SIAM short course on matrix methods, co-taught with G. W. Stewart, highlighting its role in simplifying the application of linear algebra routines for educational purposes.[7] The tool's academic roots prioritized enabling empirical validation of computational results over proprietary hardware dependencies, fostering its early adoption in university courses on matrix theory and numerical methods before any commercial adaptations.[3] This foundational approach ensured MATLAB's focus remained on verifiable, first-order numerical operations essential to engineering analysis.[1]Commercialization and Early Growth

In 1984, Cleve Moler, Jack Little, and Steve Bangert founded The MathWorks, Inc., in California to commercialize MATLAB, transforming it from an academic teaching tool distributed as freeware into a proprietary software product.[1][8] The company's initial operations were modest, with its first mailing address at a rented A-frame cabin in the hills above Stanford University where Little resided.[9] This venture capitalized on the emerging personal computing market, particularly the IBM PC introduced in 1981, by rewriting MATLAB's Fortran codebase in C to enable a PC-compatible version known as PC-MATLAB.[1] Early sales targeted universities and engineering departments, where MATLAB's matrix-oriented syntax addressed needs in numerical computing that were underserved by existing tools like Fortran libraries or early spreadsheets.[10] PC-MATLAB Version 1.0 debuted publicly in December 1984 at the IEEE Conference on Decision and Control in Las Vegas, marking MATLAB's first commercial release for MS-DOS on IBM-compatible PCs.[10][1] This version introduced a licensing model that supported ongoing development through updates and expansions, effectively resembling a subscription structure by requiring purchases for new releases and tool extensions.[10] Little and Bangert contributed key enhancements, including improved graphics and user interface elements, which facilitated its appeal to control engineers and signal processors seeking rapid prototyping without low-level programming.[10] MATLAB's early growth in the late 1980s and 1990s stemmed from the introduction of domain-specific toolboxes, beginning with those for control systems and signal processing, which extended the core language to handle specialized applications like linear system analysis and digital filtering.[10] These add-ons, such as the Control System Toolbox (initially released as Pro-MATLAB in the mid-1980s), enabled users to model dynamic systems and design controllers interactively, driving adoption in academia and industry sectors like aerospace and automotive engineering where empirical validation through simulation was increasingly valued.[1] The causal mechanism for market expansion lay in this modular extensibility: toolboxes lowered barriers to applying advanced mathematics, fostering user-contributed extensions and positioning MATLAB as a de facto standard for technical computing by the early 1990s.[10]Expansion Through Acquisitions and Milestones

MathWorks pursued strategic acquisitions to bolster MATLAB's capabilities in code verification and simulation. In April 2007, the company acquired PolySpace Technologies, a Grenoble-based firm specializing in static analysis tools for detecting runtime errors in embedded C code.[11] This integration added Polyspace products to the MATLAB and Simulink portfolios, enabling formal verification methods that mathematically prove the absence of certain errors, such as overflows or divisions by zero, thereby enhancing reliability in industries requiring certified software, including avionics and automotive systems.[11] The acquisition exemplified MathWorks' focus on augmenting core simulation strengths with complementary technologies derived from specialized engineering needs. Further expansions included the 2018 acquisition of Vector Zero, developers of RoadRunner software for procedural generation of road networks in simulation environments.[12] RoadRunner extended MATLAB's and Simulink's reach into autonomous vehicle testing by facilitating rapid creation of drivable 3D scenes from HD maps and OpenDRIVE data, supporting scenario-based verification without external dependencies. These moves, funded through internal revenues as a privately held entity, prioritized empirical enhancements to the ecosystem over subsidized research, aligning with user-driven demands for integrated, high-fidelity modeling tools. Product milestones reinforced this growth, notably the overhaul of object-oriented programming in MATLAB R2008a (version 7.6), released in March 2008.[13] This update introduced theclassdef syntax, multiple inheritance, and property validation, supplanting earlier handle and value class systems to better accommodate complex, modular codebases in engineering workflows.[14] Such adaptations stemmed from community feedback and performance benchmarks, enabling scalable development without shifting to alternative languages. Similarly, the internal development of SimEvents, a discrete-event simulation toolbox integrated with Simulink, expanded hybrid modeling for queues, servers, and stochastic processes, addressing latencies in communication and manufacturing systems through market-responsive innovation.[15]

Evolution in the 21st Century

In the early 2000s, MATLAB adapted to the proliferation of multi-core processors by introducing the Parallel Computing Toolbox in release R2008a, which enabled distribution of computational workloads across multiple CPU cores using constructs like parfor loops for iterative matrix operations.[16] This shift leveraged hardware advances, with benchmarks indicating near-linear performance gains for embarrassingly parallel tasks, such as large-scale simulations, proportional to the number of available cores on desktops and clusters.[17] By R2010a and R2010b, support extended to GPU acceleration through gpuArray objects, allowing compatible numerical functions to execute on NVIDIA hardware with compute capability 2.0 or higher, thereby reducing computation times for algorithms like FFTs and linear algebra by factors of 10 or more in select cases.[16][18] The 2010s marked MATLAB's pivot toward cloud-native capabilities amid growing demands for distributed and scalable computing. MATLAB Online, launched as a browser-based platform, permitted execution of MATLAB code on remote servers without local installation, integrating with cloud storage services like AWS S3 for handling datasets exceeding local memory limits.[19] This facilitated collaborative workflows and on-demand resource scaling, aligning with enterprise shifts to hybrid cloud environments where MATLAB scripts could interface with virtual machines for high-throughput tasks.[20] Parallel to hardware and cloud integrations, MATLAB intensified focus on data-intensive domains post-2010, evolving toolboxes to address machine learning and statistical modeling needs driven by exponential data growth. The Statistics and Machine Learning Toolbox incorporated advanced algorithms for classification, regression, and dimensionality reduction, building on MATLAB's matrix paradigm to streamline workflows from data preprocessing to predictive modeling.[21] These enhancements supported causal inference and empirical validation in fields like engineering and finance, with MATLAB's syntax enabling rapid prototyping that outpaced general-purpose languages in iterative analysis cycles.[1]Release History

Pre-Commercial and Initial Versions

MATLAB originated in the late 1970s as an academic tool developed by Cleve Moler at the University of New Mexico to provide students with access to the LINPACK and EISPACK libraries for matrix computations without requiring direct Fortran programming.[1] This pre-commercial version, written in Fortran, functioned as a simple interactive matrix calculator supporting basic operations through an interactive shell and approximately 71 built-in functions, but lacked scripting capabilities, toolboxes, or graphics.[1] It was freely distributed to universities and research institutions prior to 1984, emphasizing empirical numerical paradigms for linear algebra tasks with limited scope confined to dense matrix manipulations.[1] The transition to commercial development began in 1983 when Jack Little and Steve Bangert rewrote the software in C for MS-DOS personal computers, leading to the release of MATLAB 1.0 in December 1984 by the newly founded MathWorks company.[1] This initial version debuted at the IEEE Conference on Decision and Control, introducing enhancements such as expanded functions, basic graphics, fast Fourier transforms, and early toolbox support like the Control System Toolbox in the subsequent Pro-MATLAB release for Unix workstations in 1985.[1] Subsequent releases progressed incrementally: version 2.0 in 1986 added further matrix handling refinements, while version 3.0 in 1987 incorporated the Signal Processing Toolbox and ordinary differential equation solvers.[22] By version 3.5 in 1990 and culminating in version 4.0 in 1992, MATLAB established core integration features, including MEX files for embedding C and Fortran code to extend functionality beyond native capabilities, and support for sparse matrices to optimize storage and computation for large-scale linear algebra problems with predominantly zero elements.[1] These upgrades enabled more efficient handling of empirical data sets in scientific computing, with sparse matrix operations demonstrating measurable performance gains in memory usage and solve times for underdetermined systems compared to dense representations.[1] Version 4.0 also previewed broader ecosystem expansions, solidifying MATLAB's foundational role in numerical analysis.[1]Major Architectural Shifts

In MATLAB R14, released in 2004, MathWorks implemented a Java-based desktop environment utilizing the Java Virtual Machine for UI rendering. This architectural pivot improved cross-platform uniformity by minimizing OS-specific variations in interface behavior and appearance across Windows, Linux, and Solaris systems.[23][24] MATLAB R2016a, issued on March 3, 2016, debuted the Live Editor, an interactive tool for embedding executable code, outputs, and formatted text within scripts. This facilitated reproducible workflows by allowing section-wise execution and inline results, addressing limitations in traditional script-based debugging and documentation.[25][26] Release R2019b, dated September 18, 2019, overhauled function name resolution precedence, elevating local functions, private functions, and package-scoped elements above path-dependent external files. The revision curbed namespace collisions—where unintended function shadowing disrupted code execution—by enforcing a more predictable search hierarchy, thereby boosting reliability in modular and large-scale projects.[27][28]Recent Releases (R2020s)

MATLAB releases in the 2020s have emphasized enhancements in deep learning, GPU acceleration, and AI integration to support advanced computational workflows. R2024a introduced major updates to the Deep Learning Toolbox, including new algorithms for designing explainable and robust neural networks, expanded GPU support for training, and improved scalability for large models.[29][30] These changes facilitated faster model deployment on hardware-accelerated systems, with functions likeimportNetworkFromPyTorch enabling seamless integration of PyTorch models into MATLAB environments.[31]

R2024b built on these by adding capabilities for converting shallow neural networks from the Statistics and Machine Learning Toolbox into deep learning objects, further bridging classical and modern AI techniques.[32] Parallelization improvements and additional pretrained models enhanced performance for tasks like computer vision and natural language processing.[30]

R2025a, released on May 15, 2025, marked a significant architectural shift with a redesigned desktop interface rebuilt using JavaScript and HTML for improved web compatibility and responsiveness, replacing legacy Java components to enable a unified codebase across platforms.[33][34] Key additions included customizable sidebars, dark mode theming, tabbed figure management, and the initial rollout of MATLAB Copilot, an AI assistant providing real-time code suggestions, autocompletions, and natural language-based code generation.[35][36] This version also evolved the Live Editor for saving scripts in standard .m format and enhanced Python integration for hybrid workflows.[33]

R2025b, released in September 2025, focused on stability enhancements and expanded MATLAB Copilot functionality, including advanced debugging aids, code explanations, and test case generation to streamline prototyping and refinement.[37][38] These updates prioritized quality improvements over new features, ensuring reliability for production environments while integrating AI assistance more deeply into coding tasks.[37]

Core Syntax and Language Features

Basic Syntax and "Hello, World" Example

MATLAB employs an interpreted, array-based programming language optimized for numerical computations, where variables represent matrices by default and operations are designed for vectorization to facilitate rapid prototyping without explicit iteration.[39][40] In this paradigm, scalars function as 1-by-1 matrices, enabling uniform handling of data from single values to multidimensional arrays.[41] The language is case-sensitive for identifiers and commands but insensitive to whitespace, except within array definitions or string literals, which supports concise interactive entry while maintaining readability.[42] A basic "Hello, World" example demonstrates output via thedisp function: disp('Hello, World'), which prints the string to the command window without returning a value for assignment.[43] Executing this in MATLAB's interactive environment (the Command Window or REPL-like interface) displays the text immediately, reflecting the language's roots in interactive matrix laboratory sessions for exploratory computation.[43] Appending a semicolon to statements, as in disp('Hello, World');, suppresses automatic output display, a convention inherited from its design for efficient session-based workflows where users often prioritize computation over verbose feedback.[44]

Vectorized operations exemplify MATLAB's efficiency in avoiding loops: for instance, a = 1:10; generates a row vector [1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10] using the colon operator for range specification.[45] Then, b = a.^2; computes the element-wise squares [1 4 9 16 25 36 49 64 81 100], leveraging the array-centric syntax to apply the power operator (denoted by .^ for element-wise distinction from matrix power *) across all elements in a single instruction.[46] This approach exploits MATLAB's optimized linear algebra routines, reducing code verbosity and execution time compared to explicit for-loops, as vectorization minimizes overhead in the underlying C/Fortran implementations.[40]

Variables, Vectors, and Matrices

MATLAB employs dynamic typing, wherein variables require no explicit declaration and can alter their class, size, or complexity during execution.[47] Assignment occurs via the equals operator, as inx = 5;, which simultaneously creates the variable if absent and infers its type from the right-hand side value.[48] This approach contrasts with statically typed languages, enabling rapid prototyping but necessitating caution with unintended type changes in iterative computations.[49]

Vectors form the foundational data structure, treated as 1-by-n row or n-by-1 column matrices. Row vectors arise from space- or comma-separated elements within brackets, such as v_row = [1 2 3];, while column vectors use semicolons: v_col = [1; 2; 3];.[50] The colon operator generates sequences efficiently, e.g., 1:5 yields [1 2 3 4 5], supporting vector creation, indexing, and loop bounds without explicit loops.[45] Matrices extend this by concatenating vectors horizontally with spaces or vertically with semicolons, as in A = [1 2; 3 4]; for a 2-by-2 array.[50]

Arithmetic operations distinguish matrix multiplication (A * B) from element-wise multiplication (A .* B), with the former requiring compatible inner dimensions for standard linear algebra tasks.[51] Inversion via inv(A) computes the matrix such that , where is the identity, but direct inversion risks numerical instability for ill-conditioned matrices; built-in solvers like A \ b (mldivide) prioritize stability by selecting appropriate algorithms, such as LU or QR decomposition, over explicit inverses.[52][53] The eig(A) function computes eigenvalues and optionally eigenvectors, leveraging optimized LAPACK routines for accuracy on symmetric or general matrices.[54]

Since release R2016b, MATLAB supports automatic broadcasting (implicit expansion) in array operations, expanding compatible arrays element-wise without loops or explicit replication via repmat or bsxfun.[55] For instance, adding a row vector to a matrix broadcasts the vector across rows, yielding efficient, readable code. Vectorization—replacing loops with array operations—exploits SIMD instructions, optimized memory access, and multithreading in built-ins, often outperforming explicit loops by orders of magnitude for large arrays, as loops incur overhead from interpreted execution and lack compiler-level optimizations.[56][57] This paradigm underscores MATLAB's design for numerical computing, where matrix-oriented syntax minimizes errors and accelerates linear algebra workflows compared to scalar-loop alternatives in languages like C or Python without equivalent libraries.[56]

Functions, Structures, and Handles

MATLAB supports modular code organization through functions, which encapsulate reusable computations and promote a functional programming paradigm. Functions are defined using the syntaxfunction [outputs] = functionName(inputs), where outputs are optional and enclosed in square brackets if multiple, and the function body follows until an end keyword or file end.[58] Local functions within a script or primary function file begin with their own function statement and share the file's workspace, enabling organized subroutines without separate files.[59] This structure facilitates code reuse and testing, as functions can accept inputs like scalars, arrays, or cell arrays and return corresponding outputs.

Structures provide a flexible container for heterogeneous data, grouping related elements under named fields accessible via dot notation, such as s.fieldName = value. A structure array s = struct('field1', value1, 'field2', value2) initializes fields that can hold any MATLAB data type, including nested structures or arrays of varying sizes across elements.[60] This field-based access supports intuitive data organization, akin to records in other languages, and allows dynamic field addition or removal, e.g., s.newField = [];, making structures suitable for representing complex entities like simulation parameters or experimental results without fixed schemas.[61]

Function handles, denoted by the @ operator as in fh = @functionName, represent functions as first-class data types, enabling their passage to other functions for higher-order operations like numerical integration or optimization without relying on object-oriented constructs.[62] Anonymous function handles, such as fh = @(x) sin(x), inline simple expressions directly, supporting immediate parameterization and closure over variables. Nested functions further enhance modularity by inheriting the scope of enclosing functions, allowing shared access to outer variables without explicit passing, which mitigates reliance on global variables and associated maintenance issues in large-scale codebases.[63] For instance, a nested function can modify an outer loop counter, enforcing lexical scoping that aligns with causal dependencies in computations.[63]

MATLAB .m files, used for functions and scripts, support Unicode characters in comments and code. As of R2020a, the Editor saves new .m files by default in UTF-8 encoding without a byte-order mark, enabling seamless storage and display of non-ASCII characters, such as Persian, via standard Save or Save As operations.[64] In earlier versions, non-ASCII characters may appear corrupted; users can mitigate this by selecting UTF-8 in Save As (if available) or saving the file in an external editor like Notepad++ with UTF-8 encoding. For better Unicode display in the console, execute feature('DefaultCharacterSet', 'UTF-8').[65]

Advanced Capabilities

Object-Oriented Programming and Classes

MATLAB introduced support for object-oriented programming in release R2008a through theclassdef syntax, which defines classes as blocks of code encapsulating data properties and associated methods. This feature enables inheritance, polymorphism, and operator overloading while preserving the language's foundational array-centric paradigm, allowing extensible designs for complex simulations and algorithms without requiring retrofits to built-in functions.[66][67]

Classes consist of properties for data storage and methods for operations, with properties supporting attributes to control behavior. The Dependent attribute designates properties computed dynamically via getter methods upon access, avoiding persistent storage and enabling derived values like calculated statistics from other data. The Transient attribute prevents properties from being saved during object serialization or transmission, useful for temporary or computationally intensive elements that should not persist across sessions.[68]

MATLAB's hybrid semantics distinguish value classes, which copy objects on assignment to enforce immutability similar to built-in numeric types, from handle classes, which pass references to permit shared mutable state without duplication. Value classes suit stateless data aggregation, while handle classes facilitate scenarios like event-driven systems or graphs where modifications should propagate across references, though they introduce method dispatch overhead for property access compared to direct struct usage.[69][70]

In toolboxes, classes underpin extensible components such as custom data types for signal processing or iterative solvers, integrating with MATLAB's matrix operations for domain-specific extensions like financial instruments or control systems. For instance, handle classes enable listener patterns in graphics or simulation objects, supporting modular designs; however, benchmarks reveal property read/write latencies in classes exceed those of structs by factors of 10-100 times, limiting their use for high-frequency numerical tasks in favor of lighter alternatives.[71][72]

Graphics, Visualization, and GUI Development

MATLAB's graphics system supports a wide array of 2D and 3D visualization functions designed for rendering numerical data, with the foundationalplot function enabling line plots from vectors x and y, customizable via arguments for line styles, markers, colors, and axis properties. These plots can be extended to multiple lines or subplots using handles to figures and axes objects, allowing programmatic control over appearance and interactivity, such as zooming and panning. For plotting matrices with customized x-axis labels, the imagesc function can be used for basic visualization, followed by setting xticks and xticklabels. Example: A = rand(10,5); imagesc(A); xticks(1:5); xticklabels({'Jan','Feb','Mar','Apr','May'}); xlabel('Months'); For enhanced control in releases from R2017a onward, the heatmap function allows direct specification: h = heatmap(A); h.XDisplayLabels = {'label1','label2',...}; This integrates naturally with MATLAB's graphics capabilities for data visualization.[73][74][75]

For 3D visualizations, the mesh function produces wireframe surfaces from matrix data, displaying edges without filled faces to emphasize grid structure and height variations.[76] Complementing this, surf generates filled surface plots with interpolated faces, where users can apply lighting effects via functions like camlight and light to simulate realistic shading and highlight contours, aiding in the interpretation of complex scalar fields.[77] These tools, integral to MATLAB since its inception for numerical analysis, facilitate rapid prototyping of data-driven insights without reliance on external libraries.[78]

GUI development in MATLAB centers on App Designer, available since release R2016a, which provides a drag-and-drop interface for assembling UI components like buttons, sliders, and axes, paired with a code editor for defining callbacks through object handles.[79] This approach supports responsive apps that integrate visualizations directly, such as embedding dynamic plots updated via user interactions, with automatic layout management for desktop and web deployment.[80]

Release R2025a introduced a transition from Java-based to WebGL-based rendering for graphics and apps, leveraging JavaScript and HTML for improved cross-platform consistency, reduced crashes, and enhanced web export capabilities.[81] This shift yields measurable performance gains, including faster rendering speeds in browser environments—up to 2-3 times quicker for complex surfaces in benchmarks—while maintaining full compatibility with existing plot functions.[82]

Parallel Computing and Performance Optimizations

The Parallel Computing Toolbox facilitates scalable computations by distributing workloads across multiple cores, machines, or GPU devices, with core features includingparfor loops for automatic parallelization of independent iterations and spmd blocks for explicit single-program multiple-data execution on worker processes.[83][84] Introduced in November 2004 as the Distributed Computing Toolbox and later expanded, the toolbox manages parallel pools—groups of worker MATLAB sessions—that automatically handle data transfer and synchronization for constructs like parfor, enabling speedups proportional to available cores for embarrassingly parallel tasks such as Monte Carlo simulations.[85][86] For cluster-scale operations, integration with MATLAB Parallel Server supports job submission to schedulers like PBS or Slurm, distributing arrays via codistributed objects to minimize communication overhead in large-scale linear algebra or parameter sweeps.

GPU acceleration, enabled through gpuArray objects since MATLAB R2010b, stores data in GPU memory and extends over 1,195 built-in functions—including matrix multiplications and FFTs—to NVIDIA CUDA devices as of R2024b, with automatic kernel generation for element-wise operations via arrayfun or pagefun.[87][88] Empirical benchmarks demonstrate significant speedups for compute-intensive matrix operations; for instance, vectorized eigenvalue decompositions on a GPU yield up to 35 times faster execution than equivalent CPU loops, though small-array transfers incur latency costs that diminish gains below thresholds like 10,000 elements per dimension.[89][90] These capabilities leverage GPU parallelism for data-parallel kernels, but require single-precision data or batched operations to maximize throughput, as double-precision performance remains limited by hardware architecture.[91]

Performance optimizations in MATLAB emphasize vectorization—replacing explicit loops with array-wide operations—as the foundational technique, exploiting pre-optimized C and Fortran backends like BLAS for linear algebra, which circumvents interpreter overhead and yields 10-100x speedups over scalar loops in prototyping scenarios.[92] This approach causally enables rapid iteration in numerical algorithm development, where matrix-oriented syntax aligns with hardware vector units, outperforming naive implementations in compiled languages for exploratory tasks despite MATLAB's interpretive nature.[93] Combining vectorization with parallel features, such as GPU-accelerated parfor, further amplifies scalability; however, profiling via gputimeit or tic/toc reveals bottlenecks like memory-bound operations, necessitating data-type reductions (e.g., single vs. double) for optimal resource utilization.[90][89]

Ecosystem and Extensions

Toolboxes for Specialized Domains

MATLAB offers a suite of proprietary toolboxes that extend its core functionality into specialized domains, providing rigorously tested algorithms and functions developed by MathWorks engineers to address domain-specific challenges with empirical validation through benchmarks and real-world applications.[6] These toolboxes, exceeding 100 in number across categories like signal processing, statistics, and machine learning, incorporate optimized implementations that reduce the need for users to develop and verify custom code from scratch.[94] Licensing typically occurs as add-ons or bundles, with MathWorks documentation highlighting time savings in prototyping and analysis as a key benefit, supported by internal testing showing faster execution compared to equivalent user-coded alternatives.[95] The Signal Processing Toolbox includes functions for spectral analysis, such as thefft function, which computes the discrete Fourier transform using fast Fourier transform algorithms automatically selected based on input size for optimal performance, alongside tools for filter design, resampling, and power spectrum estimation validated on standard signals like sinusoids and noise-corrupted data.[96][97][98]

The Statistics and Machine Learning Toolbox provides capabilities for hypothesis testing, including t-tests, chi-square tests, and analysis of variance (ANOVA), which assess statistical significance from sample data against null hypotheses, with functions like ttest and anova1 incorporating assumptions such as normality and independence verified through empirical distributions and simulations.[99][100][21]

For advanced applications, the Deep Learning Toolbox enables convolutional neural network (CNN) training via functions like trainNetwork, supporting transfer learning by fine-tuning pretrained models such as AlexNet on custom datasets, with benchmarks demonstrating classification accuracies comparable to state-of-the-art on datasets like CIFAR-10 when adapting layers for feature extraction and classification.[101][102][103] These toolboxes maintain proprietary optimizations, ensuring consistency and reliability across MATLAB releases while linking development to validated outcomes in fields like engineering and data science.[6]

Integration with Simulink and Other MathWorks Products

Simulink serves as a graphical extension to MATLAB, enabling the modeling and simulation of dynamic systems through block diagrams that represent multidomain physical and control systems.[104] This integration allows MATLAB algorithms to be directly embedded into Simulink models via MATLAB Function blocks or S-functions, facilitating parameterization and customization of model behaviors with scripted computations.[105] For instance, users can leverage MATLAB scripts to generate lookup tables, tune parameters dynamically during simulation, or process simulation outputs for analysis, streamlining the transition from algorithmic prototyping in MATLAB to system-level verification in Simulink.[106] Embedded Coder extends this synergy by automating the generation of optimized C and C++ code from Simulink models, supporting deployment to embedded hardware without manual recoding.[107] The tool ensures compliance with industry standards such as MISRA C for automotive applications and DO-178C for aerospace certification, as verified through qualified toolchains that produce traceable, production-ready code. In model-based design workflows, this capability reduces development time by enabling early verification of generated code against hardware-in-the-loop tests, with case studies in automotive control systems demonstrating reductions in integration issues and improved product quality.[108] Stateflow complements Simulink by providing a graphical formalism for designing finite state machines and hybrid systems logic, integrated seamlessly within Simulink models to handle event-driven behaviors alongside continuous dynamics.[109] Transitions and states in Stateflow charts can invoke MATLAB functions for computations, enabling causal modeling of supervisory control and fault management in complex systems.[110] This ecosystem cohesion, part of MathWorks' model-based design paradigm, fosters iterative refinement from high-level simulation to deployment, though it reinforces proprietary dependencies by optimizing workflows across MATLAB, Simulink, and add-ons like Stateflow for industries requiring certified reliability.[111] Industry applications, such as in automotive reactive systems, highlight how these integrations minimize defects through simulation-driven validation before physical prototyping.[112]Interoperability and Compatibility

Interfaces with External Languages and APIs

MATLAB supports integration with external languages primarily through MEX files, which enable the execution of C, C++, or Fortran code as native functions within the MATLAB environment to accelerate performance-critical computations.[113] MEX functions are compiled binaries that interface directly with MATLAB's matrix API, allowing seamless data exchange without explicit copying in many cases, though users must manage memory allocation via MATLAB's mxArray utilities.[114] This mechanism is particularly effective for numerical algorithms where MATLAB's interpreted nature incurs overhead, with benchmarks showing speedups of 10-100x for compute-intensive loops compared to pure MATLAB implementations, depending on the algorithm's vectorization potential.[115] For invoking Python code from MATLAB, thepy. namespace provides a foreign function interface introduced in release R2014b, permitting direct calls to Python modules and libraries such as NumPy or TensorFlow by prefixing function names.[116] Data types are automatically converted between MATLAB arrays and Python equivalents (e.g., double to numpy.ndarray), but this incurs serialization overhead for large datasets, often limiting efficiency to scenarios where Python's ecosystem offers unique optimizations unavailable in native MATLAB toolboxes.[117] Empirical tests indicate that while small function calls add negligible latency, iterative exchanges of multi-gigabyte matrices can degrade performance by factors of 2-5 relative to in-process operations, favoring hybrid workflows that minimize boundary crossings.[115]

Conversely, the MATLAB Engine API facilitates embedding MATLAB as a computational engine within external applications written in C, Fortran, Java, Python, or .NET, enabling calls to MATLAB functions from host languages for leveraging its matrix operations in non-MATLAB environments.[118] For instance, the Python implementation launches a MATLAB session via the matlab.engine package, supporting synchronous execution and data transfer, which is useful for integrating legacy MATLAB code into Python pipelines but introduces process startup costs (typically 1-5 seconds) and inter-process communication latency.[119] In Java, the API supports both synchronous and asynchronous modes, with similar trade-offs where gains accrue from MATLAB's specialized solvers outweighing marshalling expenses in data-parallel tasks.[120] Overall, these interfaces enable modular architectures but require profiling to balance interoperability benefits against invocation overheads, as excessive cross-language calls can negate acceleration from optimized external libraries.[121]

Relations to Open-Source Alternatives

GNU Octave serves as a free, open-source alternative designed for high compatibility with MATLAB's core syntax and matrix-oriented operations, allowing many MATLAB scripts to run with minimal modifications. However, Octave falls short in replicating MATLAB's extensive toolbox ecosystem, with fewer specialized functions for domains like signal processing, control systems, and optimization, often requiring community-contributed packages that lack the rigorous testing and integration of MATLAB's proprietary equivalents.[122][123] Evaluations indicate that while Octave handles basic numerical computations adequately, its toolboxes exhibit inconsistencies in performance and completeness for advanced applications.[124] Python, augmented by libraries such as NumPy for array manipulation, SciPy for scientific algorithms, and Matplotlib for visualization, competes as a versatile open-source ecosystem for numerical and scientific computing. Benchmarks reveal MATLAB's advantages in integrated prototyping speed for linear algebra and matrix operations, where it often outperforms Python by factors of 5-10 in summation and multiplication tasks on large arrays, due to optimized just-in-time compilation.[125][126] Conversely, Python excels in scalability through parallel processing across multiple cores and broader interoperability with machine learning frameworks like TensorFlow, fostering community-driven extensions that address evolving needs beyond MATLAB's core focus.[127][128] The proprietary structure of MATLAB enables sustained investment in a cohesive, polished environment, including validated toolboxes and performance optimizations, which proprietary funding supports through dedicated engineering teams. In contrast, open-source alternatives like Octave and Python rely on distributed volunteer contributions, promoting wider accessibility and rapid adaptation to niche innovations but risking fragmented maintenance and slower resolution of specialized gaps, as evidenced by comparative studies on software ecosystems in scientific domains.[129][130] This dynamic underscores how closed-source models incentivize comprehensive reliability for enterprise use, while open-source prioritizes extensibility at the potential cost of uniformity.[131]Commercial Model

Licensing Structure and Pricing

MATLAB's licensing is managed exclusively by MathWorks, offering a range of proprietary options tailored to individual users, commercial entities, academic institutions, and personal non-commercial use, all requiring activation through MathWorks accounts. Commercial individual licenses operate on a subscription model at USD 1,015 annually (excluding taxes), encompassing base MATLAB functionality and one year of Software Maintenance Service (SMS) for updates, bug fixes, and technical support; without renewed SMS, users retain access only to the licensed version without new releases.[95] Perpetual licenses remain available for select categories like academic teaching and research or personal Home use, permitting indefinite operation of the purchased version, though they include only the initial year's SMS, with subsequent renewals—typically 20-30% of the base price—necessary for ongoing enhancements and compatibility.[95] [132] Academic licensing differentiates by scope: student versions, such as the MATLAB and Simulink Student Suite, provide subscription access to core products plus select add-ons at reduced rates (around USD 99-500 annually, varying by region and eligibility), verifiable through institutional affiliation.[133] Campus-wide licenses for universities enable unlimited deployment across faculty, staff, and students, often negotiated per institution and including extensive toolboxes, reflecting bulk pricing that can exceed USD 100,000 annually for large deployments to sustain broad accessibility while funding development.[134] Home licenses for personal, non-commercial use start at approximately USD 149 for perpetual access to a single version or subscription equivalents, explicitly barring professional or educational applications.[135] Toolboxes and add-ons, essential for domain-specific extensions like signal processing or machine learning, are priced separately as modular purchases, with individual commercial licenses ranging from USD 500 to over USD 4,000 each, bundled in higher-tier plans like startup programs that include 90+ add-ons for USD 500-1,000 monthly during early stages.[136] [137] This structure incentivizes incremental revenue, as base MATLAB alone suffices for basic numerical computing, but advanced workflows—prevalent in engineering and research—demand multiple toolboxes, often comprising the majority of total licensing expenditures. Concurrent or network licenses for organizations scale costs by simultaneous users or seats, typically requiring custom quotes to accommodate enterprise deployment.[95] All licenses enforce single-vendor dependency, with no open-source equivalents bundled, ensuring MathWorks controls updates and feature evolution through mandatory renewals.[138]Business Sustainability and Market Position

MathWorks, the developer of MATLAB, reported annual revenue of $1.5 billion as of 2025, with consistent profitability achieved every year since the company's founding in 1984.[139] This financial stability stems from a private ownership structure held by co-founders Jack Little and Cleve Moler, which avoids shareholder pressures and enables sustained investment in research and development without reliance on external debt or public markets. The firm employs over 6,500 people across 34 global offices, supporting a diversified customer base that includes academic institutions, government agencies, and enterprises in sectors such as aerospace, automotive, and pharmaceuticals.[139] MATLAB maintains a dominant market position in proprietary numerical computing and simulation software, serving approximately 5 million users worldwide.[140] Its ecosystem of specialized toolboxes and seamless integration with hardware-in-the-loop testing and model-based design—particularly via Simulink—creates high barriers to entry for competitors, fostering vendor loyalty in engineering workflows where rapid prototyping and validation are critical. While open-source alternatives like Python with NumPy/SciPy libraries have gained traction for general-purpose data analysis due to cost advantages, MATLAB's entrenched role in regulated industries and legacy codebases sustains its revenue streams, with adoption rates remaining robust among Fortune 500 companies for tasks requiring certified, domain-specific extensions.[141] Business sustainability faces pressures from the commoditization of basic matrix operations and visualization tools, yet MathWorks counters this through continuous innovation, such as GPU acceleration and cloud deployment options introduced in recent releases, which extend MATLAB's applicability to large-scale simulations. The company's avoidance of acquisitions for core growth—focusing instead on organic development—has preserved operational efficiency, though a ransomware incident in August 2025 disrupted licensing services temporarily without long-term revenue impact. Overall, MATLAB's market position reflects a niche monopoly in high-value engineering applications, where the total cost of ownership, including productivity gains from proprietary features, outweighs free alternatives for many professional users.[140]Criticisms and Technical Limitations

Syntax and Usability Shortcomings

MATLAB employs 1-based indexing for arrays, diverging from the 0-based convention dominant in languages such as C, Python, and Java, which predisposes code to off-by-one errors, especially during integration with zero-indexed external libraries or data formats where boundary assumptions mismatch.[142] This design, rooted in mathematical notation for counting from 1, complicates mental mapping for developers accustomed to offset-based addressing, amplifying bugs in loops and slicing operations that span language boundaries.[143] Complementing this, MATLAB's column-major storage order—elements of columns contiguous in memory, akin to Fortran—clashes with the row-major layout standard in C-derived ecosystems, requiring explicit transpositions (e.g., viapermute or reshape) when exchanging matrix data, a frequent source of shape mismatches and silent errors in hybrid workflows.[144][145] The square bracket operator [] exacerbates ambiguity by doubling as an empty matrix indicator and a concatenation tool, where horizontal ([A B]) versus vertical ([A; B]) assembly hinges on spacing or semicolons; unintended flattening occurs when juxtaposing cell or string arrays, as [] defaults to concatenation over preservation, demanding workarounds like explicit cell constructors.[146]

Operator overloading introduces further unintuitiveness, as arithmetic symbols apply numeric semantics to non-numeric types: adding an integer to a character array shifts ASCII values ('a' + 1 yields 'b'), treating text as encoded integers rather than abstract strings, which derails expectations in mixed-type expressions and necessitates type guards absent in dedicated string operators.[142] Prior to release R2016b, string manipulation relied on character arrays—matrices of numeric codes—lacking native vectorized methods for common tasks like splitting or pattern matching, forcing reliance on matrix-oriented functions (e.g., strcat for concatenation) that scale poorly and invite dimension errors in text-heavy pipelines.[147][148] The native string type introduced in R2016b mitigated some issues by enabling array-friendly operations, yet legacy codebases perpetuate friction, with computational scientists reporting cumulative maintenance burdens from these design choices over alternatives like Python's distinct string primitives.[142]