Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Saint David.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Saint David

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

Not found

Saint David

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

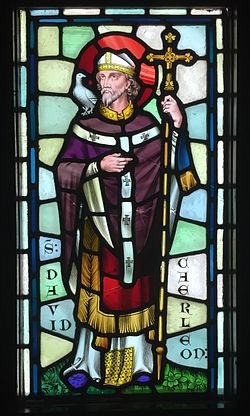

Saint David (Welsh: Dewi Sant; c. 500 – 1 March 589) was a 6th-century Welsh bishop and abbot who founded a monastic community at Mynyw in southwestern Wales, the site of the present-day St David's Cathedral, and is venerated as the principal patron saint of Wales.[1][2][3] Historical knowledge of his life derives primarily from the Vita Sancti Davidis, a hagiographical account composed around 1090 by Rhygyfarch, son of Bishop Sulien of St David's, which draws on oral traditions but includes legendary elements such as miraculous events and extreme ascetic practices, reflecting later medieval embellishments rather than contemporary records.[1][2] David attended a synod at Brefi where he reportedly preached against Pelagianism, leading to his elevation as bishop, and emphasized communal monasticism, manual labor, and simplicity among his followers.[4][5] He was canonized by Pope Callixtus II in 1120, with his feast day on 1 March becoming a national observance in Wales, marked by traditional symbols like the daffodil and leeks, though primary evidence for his cult's early spread remains tied to post-Norman ecclesiastical promotion at St David's.[5][3]

Early Life and Origins

Birth and Family Background

Saint David, known in Welsh as Dewi Sant, was born in the late fifth or early sixth century AD on the southwestern coast of Wales, in the region of Pembrokeshire near what is now St. David's.[4][6] The precise date remains unknown due to the absence of contemporary records, with scholarly estimates ranging from 462 to 515 AD and traditional accounts favoring circa 500 AD.[6][3] Legends describe his birth occurring amid a violent storm on a cliffside, marked by miraculous signs such as the ground opening to shield his mother from rain and the sun shining directly upon her.[4] These details originate from hagiographical texts composed centuries later, which incorporate symbolic elements rather than verifiable historical data. David was the son of Sandde (also called Sant or Sanctus), a nobleman or prince associated with the kingdom of Powys, and Non (or St. Nonnita), daughter of a chieftain from the Menevia region.[4][3] Non is portrayed in traditions as a devout nun or holy woman, and David's conception is attributed in some accounts to an assault by Sandde, emphasizing themes of divine intervention amid human frailty.[7] Both parents descended from Welsh royal lineages, with David identified as the grandson of Ceredig ap Cunedda, the eponymous founder-king of Ceredigion, linking him to the broader dynasties that shaped post-Roman Wales.[3] No historical records mention siblings, and family details are absent from any sixth-century sources, deriving instead from vitae like Rhygyfarch's eleventh-century Life of St. David, which served ecclesiastical and cultural purposes more than strict historiography.[6] Such accounts, while influential in Welsh tradition, reflect medieval embellishments on scant early evidence, prioritizing saintly origins over empirical genealogy.Education and Early Monastic Influences

According to the Vita Sancti Davidis composed by Rhygyfarch around 1090–1100, David's early education occurred at the monastery known as Vetus Rubus (Latin for "Old Bush," traditionally identified with Henfynyw in Ceredigion, Wales), where he was instructed in the alphabet, psalms, and celebration of masses.[8] This account, the earliest detailed biography of David, portrays his learning as divinely aided, with a dove symbolizing the Holy Spirit perched on his shoulder during lessons, though such elements reflect hagiographical embellishment rather than empirical record.[8] Henfynyw, an ancient site with an inscribed stone dating to the 6th–7th century, is associated with early Celtic monastic communities and serves as the traditional locus of David's infancy and initial formation.[9] David subsequently completed his studies under Paulinus (also called Pawl Hen), a late 5th-century monk described as a disciple of Germanus of Auxerre and renowned for scriptural expertise.[10] Traditions hold that he spent approximately ten years at Whitland (Welsh: Hengwrt or Ty Gwyn) in Carmarthenshire, immersing himself in the Holy Scriptures and becoming a skilled scribe and priest.[11] [10] Paulinus, who suffered from blindness in old age, is said to have been healed by David's sign of the cross, underscoring the mentor-disciple bond in Rhygyfarch's narrative.[8] This period emphasized ascetic discipline, scriptural exegesis, and clerical preparation within the Insular Celtic tradition, which drew from patristic sources via figures like Germanus, linking British monasticism to continental influences without direct Egyptian ties at this stage.[10] These formative experiences shaped David's commitment to rigorous monasticism, including vows of chastity and manual labor, as he transitioned from pupil to teacher and founder.[8] While contemporary 6th-century records are absent—David's historicity rests on later vitae and references in texts like the 9th-century Catalogue of the Welsh Saints—archaeological continuity at sites like Henfynyw supports the plausibility of localized monastic education in post-Roman Britain.[8]Ecclesiastical Career

Monastic Foundations

Saint David established monastic communities in southwestern Britain during the sixth century, emphasizing ascetic discipline, manual labor, and scriptural study. His primary foundation was at Mynyw (modern St David's, Pembrokeshire), where he created a rigorous monastic settlement that became a hub for Welsh Christianity and learning.[1] This site, attested in early traditions, likely originated as a cell of hermits before expanding under David's leadership around 550 CE.[12] Prior to Mynyw, David founded a monastery at Glyn Rosyn (Vale of Roses), a secluded valley near the coast, which served as an initial base for his disciples.[13] Traditions describe his communities as practicing severe austerity, including tilling the soil without draft animals, abstaining from meat and alcohol, and bathing in cold river waters daily.[5] The eleventh-century Vita Davidis by Rhygyfarch attributes to him the foundation of twelve monasteries across Wales, Dumnonia, and possibly Brittany, naming sites such as Glastonbury, Bath, and Leominster.[8] However, these claims lack contemporary corroboration and reflect later hagiographical embellishment to elevate David's legacy, with only the Mynyw foundation widely accepted as historical by scholars due to its continuity and early references in sources like the c. 730 Irish Catalogue of Saints.[14] Archaeological evidence at St David's supports a sixth-century monastic origin, including early Christian burials and structures predating Norman reconstructions.[15] David's establishments influenced the Celtic monastic model, prioritizing abbatial authority over episcopal hierarchy initially.[16]Role at the Synod of Brefi

The Synod of Brefi, convened around 545 AD in what is now Llanddewi Brefi, Ceredigion, Wales, addressed the resurgence of Pelagianism—a doctrine originating from the 5th-century British theologian Pelagius that emphasized human free will and denied the necessity of divine grace for salvation, thereby rejecting original sin's transmission.[17][18] This gathering of Welsh ecclesiastical leaders, including bishops and clergy, aimed to reaffirm orthodox Christian teachings amid lingering influences from earlier Pelagian controversies condemned at councils like Ephesus in 431 AD.[19] Historical accounts, primarily drawn from 11th-century hagiographical vitae rather than contemporary records, indicate the synod's scale included numerous participants, though claims of 118 bishops likely reflect later embellishment to underscore its significance.[20] Saint David, then a prominent monastic leader prior to his formal episcopal consecration, was invited to participate, reportedly at the urging of the aged bishop Paulinus, a former mentor, to counter Pelagian arguments advanced by figures associated with Saint Cadoc.[21][22] David's role centered on delivering a persuasive oration that decisively refuted the heresy, leveraging his reputation as an eloquent speaker and ascetic authority; traditional narratives describe him rising on an improvised mound—said to have miraculously elevated beneath his feet—to ensure his voice carried to the assembled crowd near the River Teifi.[23][24] This intervention, as recounted in Rhygyfarch's Vita Sancti Davidis (c. 1090), not only silenced opponents but also symbolized divine endorsement, with accompanying legends of a dove alighting on his shoulder and the ground yielding a spring of water.[25] The synod's outcome, per these sources, solidified David's influence, paving the way for his elevation as primate of Wales and subsequent transfer of authority from Saint Dyfrig (Dubricius), who resigned in his favor; Dyfrig consecrated David as bishop, marking a pivotal ascent in his ecclesiastical career.[13][1] While the event's historicity rests on vitae prone to hagiographic amplification—lacking corroboration from independent 6th-century documents—its depiction underscores David's doctrinal orthodoxy and rhetorical prowess in consolidating Celtic Christianity against heterodox threats.[26]Bishopric of Mynyw

Saint David, traditionally dated to the sixth century, is regarded as the founder of the monastic community at Mynyw (modern St David's, Pembrokeshire), which served as the basis for the episcopal see.[27] [28] As abbot-bishop, he presided over a rigorously ascetic establishment emphasizing manual labor, scriptural study, and communal prayer, with monks reportedly standing in cold water while reciting psalms.[29] [30] The bishopric combined monastic and diocesan authority, reflecting early Celtic church practices where abbots often held episcopal roles without fixed territorial boundaries.[31] Historical evidence for David's episcopate derives primarily from vitae composed centuries later, such as the eleventh-century Life by Rhigyfarch, which portrays him as consecrated bishop at Mynyw following the Synod of Brefi, though contemporary records are absent.[2] [14] Archaeological and sculptural remains indicate continuous Christian activity at the site from the early medieval period, supporting the persistence of the see beyond David's lifetime, traditionally around 589.[16] The diocese of St David's, tracing its origins to this foundation, maintained independence within the Welsh church, resisting full integration into the English ecclesiastical structure until later medieval reforms.[32] [33]Later Life and Death

Ascetic Practices

Saint David practiced extreme asceticism, emulating the desert fathers of Egypt through rigorous self-denial, as described in Rhygyfarch's Vita Sancti Davidis, composed around 1099 based on earlier traditions.[8] His regimen emphasized subduing the flesh via fasting, prolonged prayer, and physical toil, rejecting comforts such as intoxicants and animal assistance in labor.[8] This lifestyle earned him the epithet Dyfrwr (Waterman) in Welsh sources, reflecting his abstinence from beer or wine and reliance solely on water.[34] David's diet consisted primarily of bread and water, occasionally supplemented with herbs and salt to sustain the body without indulgence, a rule enforced in the monasteries he founded to prevent carnal excess.[8] Meat was entirely prohibited, aligning with his broader rejection of luxuries that could inflame desires.[8] He fasted overnight during times of communal adversity and limited meals to one daily, often after laborious prayer, ensuring physical sustenance served spiritual discipline rather than pleasure.[8] Prayer formed the core of his daily routine, involving ceaseless vigils, genuflections, and readings of Scripture from dawn until stars appeared, with no sleep interrupting the cycle.[8] He spent whole days in solitary or communal prayer, adding three hours of prostrations post-evening worship, and observed continuous watchings from Sabbath eve through Sunday matins, tearfully interceding for the Church.[8] Such practices, conducted in silence and meditation, mirrored the ascetic intensity of early Christian hermits, fostering inner purity amid external rigor.[8] Manual labor was mandatory under David's rule, with monks wielding tools like mattocks, spades, and saws to till fields without oxen or plows drawn by beasts, carrying all provisions themselves to cultivate humility.[8] Silence prevailed during these tasks to maintain focus on divine contemplation, rejecting idleness as antithetical to monastic life.[8] To further mortify the body, David immersed himself daily in cold water, lingering until fleshly heats subsided, a penance repeated as self-imposed discipline even in advanced age.[8] His monastic disciplines extended to voluntary poverty, communal ownership without personal possessions, and simple attire of skins or coarse garments, penalizing any assertion of "mine" or "yours" with penance.[8] Novices endured ten days of rejection and verbal reproach before entry, ensuring only the resolute joined this cenobitic order modeled on Egyptian precedents.[8] These elements, while hagiographically amplified, underscore a historical commitment to apostolic simplicity amid 6th-century Welsh Christianity.[34]Death and Burial

Saint David died at his monastic community in Menevia (modern St David's, Pembrokeshire) on 1 March, with the year traditionally dated to 589 AD, though the Annales Cambriae (10th-century Welsh chronicle) records the event in 601 AD.[4] [35] The discrepancy arises from varying interpretations of early annals and hagiographical texts, with 589 aligning with Rhigyfarch's calculation in his Vita Sancti Davidis (c. 1095), the primary biographical account, which synchronizes David's lifespan with Roman consular dates.[1] According to Rhigyfarch's Vita, David received a divine premonition of his death, accepted it with pious resignation, and preached a final sermon urging ascetic discipline and charity; at his passing, the monastery was reportedly filled with angelic light and song as his soul departed.[36] This account, while incorporating miraculous elements typical of medieval vitae, preserves traditions from oral and possibly earlier written sources at Menevia, though no contemporary records survive.[35] David was buried in the church of his monastery at Menevia, where his tomb quickly became a site of local veneration.[37] The original burial site underlay the later medieval cathedral, with his remains reportedly translated to a stone sarcophagus in the 12th century amid efforts to promote pilgrimage, though Viking raids in the 11th century had damaged earlier structures housing the shrine.[4] In 1275, Bishop Thomas de Houghton moved the relics to a new oak shrine within the cathedral, enhancing its status as a major relic site until the Reformation.[1]Hagiographical Traditions

Attributed Miracles

According to Rhygyfarch's Vita Sancti Davidis (c. 1090), the primary hagiographical account of David's life composed over five centuries after his reported death, multiple miracles are ascribed to him during his lifetime to affirm his divine election and monastic authority.[8] These narratives, drawn from oral traditions and earlier lost texts, emphasize themes of healing, provision, and protection, often involving water, sight restoration, and resurrection—motifs common in Celtic saintly vitae but lacking contemporary corroboration.[38] Rhygyfarch portrays David as an ascetic "Aquatic" who subsisted on bread and water, with miracles reinforcing his primacy among British bishops.[8] Prominent among these is the miracle at the Synod of Brefi (c. 545), where David reportedly refuted the teachings of Pelagian sympathizer Paulinus; as he preached, the ground elevated beneath his feet into a small hill, enabling the assembly to see and hear him clearly, while a white dove descended to alight on his shoulder, symbolizing the Holy Spirit.[4] This event, intended to establish David's ecclesiastical preeminence, recurs in later medieval accounts but aligns with hagiographical topoi of topographical alteration seen in lives of other saints like Patrick.[39] Healing miracles predominate, including the restoration of sight to his teacher Paulinus by touch (chapter 11), to blind king Peibio of Erging during monastic foundations (chapter 13), and to a sightless monk at David's own baptism via consecrated water (chapter 7).[8] Further attributions involve prodigies of life restoration and divine safeguarding: David revived dead cattle belonging to opponent Bwya (chapter 16), resurrected a drowned boy named Magnus by the River Teivi and returned him to his mother (chapter 51), and unearthed a perennial spring with his staff to quench a neighbor's thirst (chapter 34).[8] In demonstrations of protection, he consumed poisoned bread unscathed while it slew accompanying animals (chapter 38), and withered an attacker's hand via the sign of the cross when it threatened Irish monk Modomnoc (chapter 41).[8] Prenatal miracles are also noted, such as extinguishing a fire afflicting Gildas's book from the womb, prefiguring his sanctity amid his mother Non's trials.[40] Later vitae, such as the 12th-century Welsh Buchedd Dewi, amplify these with additional legends like tears reviving a deceased youth, but retain Rhygyfarch's core emphasis on David's role as a conduit for grace rather than personal agency.[41]Vitae and Medieval Legends

The earliest surviving vita of Saint David, known as the Vita Sancti Davidis, was composed around 1090 by Rhygyfarch (also spelled Rhigyfarch), a monk and scholar at Llanbadarn Fawr and son of Bishop Sulien of St David's.[42][43] Rhygyfarch claimed to draw from ancient Welsh books, oral traditions preserved by elders, and inscriptions at David's monastic settlement of Mynyw (modern St David's), though scholars note the work's primary aim was to bolster the autonomy of the Welsh church amid Norman incursions, blending historical elements with hagiographical embellishments.[44][45] The text structures David's life into phases of birth and education, monastic foundations, ecclesiastical roles, and ascetic death, emphasizing his virtues of austerity, miracles, and orthodoxy against Pelagian influences. Rhygyfarch's vita incorporates medieval legends framing David as a divinely ordained figure. It recounts his conception as prophesied to his father, Sanctus (a prince of Ceredigion), by an angel thirty years prior, with David born amid a tempest where the earth shook and a heavenly choir sang at his baptism by his uncle, Sanctus of Cille Muir.[40][46] As an infant, David reportedly performed a miracle by restoring a bystander's sight with water from his baptismal font, symbolizing his prenatal sanctity.[40] Later legends describe his education under the blind Irish saint Paulinus (or Paul Aurelian), whom David cured, enabling the teacher to read scriptures again; his monastic rule of severe fasting, manual labor, and rejection of meat and beer; and a miracle at the Synod of Brefi (c. 545), where the ground rose beneath him like a hill to silence detractors, affirming his authority.[31] These narratives, while unverifiable, reflect Celtic hagiographic tropes prioritizing asceticism and divine favor over empirical chronology. Subsequent medieval vitae expanded on Rhygyfarch's account, often in Welsh vernacular adaptations from the 13th to 15th centuries, preserved in manuscripts like National Library of Wales Peniarth 2 and Llanstephan 27.[47] These later lives, such as the anonymous Vita Davidis in the Book of the Anchorite of Llanddew, amplify legends including David's alleged kinship to King Arthur and encounters with Irish saints like Patrick, who purportedly ceded Wales to him after a visionary meeting.[34][48] Giraldus Cambrensis (Gerald of Wales), in his 12th-century Itinerarium Cambriae, referenced and endorsed elements of Rhygyfarch's vita to argue for St David's metropolitan status, though he critiqued some monastic excesses.[49] Scholarly analysis views these vitae as composites of folklore and ecclesiastical propaganda, with Rhygyfarch's Latin original serving as the foundational text despite its anachronisms, such as projecting 11th-century canonical reforms onto 6th-century events.[50] No contemporary 6th-century records exist, rendering the legends' historicity dependent on cross-referencing with sparse sources like the Annales Cambriae.[31]Connections to Glastonbury and Other Sites

Medieval hagiographical accounts, particularly Rhygyfarch's Vita Sancti David composed around 1090, assert that Saint David founded Glastonbury among the twelve monasteries he established during his lifetime.[51] This attribution aimed to bolster the abbey's claims to exceptional antiquity and apostolic continuity, a common practice in insular monastic literature.[52] Later elaborations, such as those in William of Malmesbury's De Antiquitate Glastoniensis Ecclesiae circa 1130, depict David arriving at Glastonbury accompanied by seven bishops, over whom he presided as primate, and constructing an oratory there.[51] Additional legends preserved in Glastonbury traditions credit David with donating a large sapphire to the altar of Our Lady, an artifact said to have elicited wonder for over a millennium until its disappearance amid the 16th-century Dissolution of the Monasteries.[53] These narratives, while enhancing the site's relic status, lack corroboration in contemporary sources and reflect the abbey's efforts to forge links with prominent Celtic saints amid 12th-century rivalries for pilgrimage revenue.[4] Beyond Glastonbury, David's vitae portray him founding monastic settlements in regions of Dumnonia (modern southwest England) and Brittany, extending his influence across Celtic territories.[3] Specific sites invoked include Bath and Leominster, where traditions hold he established early churches or communities.[54] Irish hagiographical interconnections, evident in shared motifs with vitae of figures like Finnian of Clonard—under whom David purportedly trained—highlight presumed 6th-century exchanges between Britain and Ireland, though these appear as retrospective cultural alignments rather than documented events.[48]Veneration and Cult

Patronage of Wales

Saint David, known in Welsh as Dewi Sant, is the patron saint of Wales, a status rooted in his 6th-century role as a bishop and monastic founder who strengthened Christianity in the region. His influence as a preacher and leader, particularly through establishing the monastic community at Mynyw (modern St David's), contributed to the early consolidation of the Welsh Church, distinguishing it amid broader British Insular Christianity.[1][55] The formal recognition of David's patronage emerged in the medieval period, following his canonization by Pope Callixtus II in 1120, after which he was declared the patron saint of Wales. By the 12th century, more than 60 churches across Wales were dedicated to him, reflecting the widespread devotion and the growth of his cult, which drew pilgrims to his shrine at St David's Cathedral and elevated the site's status as a key ecclesiastical center.[4][56][41] David's patronage symbolizes Welsh national identity, with his feast day on March 1 observed as a cultural and sometimes public holiday, featuring traditions like wearing leeks or daffodils—plants associated with him through hagiographical accounts. As the only native-born patron saint among the home nations of Britain and Ireland, his veneration underscores a distinctly Welsh ecclesiastical heritage, independent of Anglo-Saxon or Roman impositions until later Norman influences.[3][57]Shrines and Relics

The principal shrine dedicated to Saint David stands at St David's Cathedral in Pembrokeshire, Wales, on the site of his original monastic foundation and burial place after his death on 1 March 589.[3] An early shrine was destroyed during a Viking raid in 1089, prompting the construction of a new one in 1275 under Bishop Richard de Carew, following the purported discovery of David's bones south of the cathedral.[58] This medieval shrine housed relics believed to include David's remains alongside those of Saint Justinian, his confessor, in a portable casket atop a stone base, attracting pilgrims such that papal indulgences equated two visits to St David's with one to Rome and three with one to Jerusalem by the 13th century.[58][59] During the Reformation in the 16th century, Bishop John Barlow oversaw the destruction of the shrine and removal of its relics, dispersing or losing items such as David's staff, Gospel book, bell, and portable altar, which had been guarded by local churches since the 12th century.[58][60] The stone base of the shrine survived intact, unlike many contemporary sites, and notable royal pilgrims included Henry II in 1171 and Edward I with Queen Eleanor in 1284.[58] No authenticated relics of Saint David exist today; bones once claimed as his, rediscovered in the 1920s behind the high altar, were radiocarbon-dated in the 1990s to the 12th–14th centuries, predating the 1275 shrine but incompatible with a 6th-century origin, possibly belonging to Saint Caradoc (d. 1124).[58][59] A restored version of the shrine was unveiled on 1 March 2012, featuring medieval-style icons of Saints Patrick, David, and Andrew, along with reliquaries, though without verified relics; it remains a focal point for contemporary veneration at the cathedral.[58][61]Liturgical and Cultural Observance

The liturgical feast of Saint David is commemorated on March 1 across multiple Christian traditions, marking the traditional date of his death in 589 AD. In the Roman Catholic Church, it is observed as a feast day, elevated to a solemnity within Wales, with specific propers including readings from the Common of Pastors that emphasize his role as a bishop and monastic founder.[62] [63] The Anglican Communion similarly honors him on this date as the patron of Wales, incorporating him into the calendar of saints with collects focused on his ascetic life and missionary zeal.[14] In the Eastern Orthodox Church, Saint David is venerated as a bishop of Wales, with his troparion and kontakion highlighting his humility and establishment of monasteries, reposed around 601 AD.[29] Culturally, St. David's Day (Dydd Gŵyl Dewi Sant) on March 1 serves as a national celebration of Welsh identity, featuring parades, concerts, and eisteddfodau—competitive festivals of music, poetry, and performance rooted in medieval bardic traditions.[64] Participants traditionally wear leeks or daffodils as emblems: the leek traces to a legend of David advising soldiers to identify themselves with it during battle, while the daffodil (cenhinen pedr) symbolizes renewal and became popularized in the 19th century through poetry.[57] [65] Schools across Wales mark the day with recitations of Welsh hymns, folk dances, and dramatizations of David's life, fostering language and heritage preservation; traditional foods such as cawl (lamb stew) and bara brith (fruit bread) are consumed in communal settings.[66] [67] Observances extend to Welsh diaspora communities in cities like London, New York, and Sydney, where societies host banquets and cultural events, though without official public holiday status in Wales—despite recurring legislative proposals since 2000 to designate it as such, citing its role in national pride comparable to St. Patrick's Day in Ireland.[55] These practices, documented since the 12th century, blend religious devotion with secular patriotism, emphasizing David's exhortation to "be faithful" (gwnewch y pethau bychain mewn bywyd) as a motto for perseverance.[68]Historical Evaluation

Primary Sources and Evidence

The earliest surviving biographical account of Saint David is the Vita Sancti David, composed in Latin by Rhygyfarch (c. 1056–1099), a scholar and precentor at St David's Cathedral, around 1099.[43] Rhygyfarch, son of Bishop Sulien ap Dyfgu, explicitly identifies himself as the author in the text's conclusion and states that his work draws from ancient books held at the church, eyewitness testimonies preserved orally, and inspirations from divine sources, though no pre-existing vitae are extant.[8] The Vita describes David as a 6th-century bishop-abbot of Mynyw (modern St David's), emphasizing ascetic practices, monastic foundations, and miracles, but its hagiographical nature prioritizes edification over historical chronology, with events placed loosely around c. 500–589.[34] Chronological evidence for David's existence appears in the Annales Cambriae, a Latin chronicle compiled in the mid-10th century from earlier Welsh records, which entries his death under the year 601 as "The body of Daniel [an alternative name for David] is placed on the [island of] Enlli [Bardsey] as the Annales Menei state."[34] This entry, likely derived from 7th- or 8th-century monastic annals at Bardsey or Menevia, provides the sole near-contemporary datable reference, aligning with the traditional timeframe of David's episcopate amid post-Roman British Christianity.[31] A fragmentary 7th-century Latin inscription or record at Llanddewi Brefi church, associating the site with David's synod against Pelagianism, constitutes the earliest direct written mention of him, predating Rhygyfarch by centuries and indicating an established cult by the early medieval period.[24] No documents from David's lifetime survive, and archaeological evidence at St David's Cathedral—such as excavated monastic cells and a possible 6th-century foundation layer—offers indirect corroboration of a continuous Christian community but lacks inscriptions naming David specifically.[47] Later Welsh adaptations, like the 12th-century Buchedd Dewi in Middle Welsh, derive directly from Rhygyfarch without independent primary material, underscoring the Vita's foundational role despite its composition five centuries after the events.[69] Irish recensions and references in texts like the Triads of Ireland (c. 9th–10th century) mention David peripherally in saintly genealogies but add no verifiable biographical details beyond hagiographic motifs.[69]Debates on Historicity

The historicity of Saint David rests on indirect and late-attested evidence, with no contemporary documents from the sixth century confirming his existence or activities. The earliest detailed account, Rhygyfarch's Vita Sancti David composed circa 1090, relies on oral traditions and prior written fragments, depicting David as a bishop and monastic founder active around 500–589 CE in southwestern Wales.[34] [1] This temporal gap of over 500 years invites skepticism, as hagiographies of this era often blend verifiable events with legendary motifs to elevate saints' status, a pattern observed in Celtic vitae where miracles and exaggerated asceticism serve didactic purposes rather than historical reportage.[70] Scholars affirm a historical core to David's figure based on corroborative elements across sources. The monastic regimen described in Rhygyfarch—emphasizing manual labor, dietary austerity, and immersion in cold water—aligns closely with the independent observations of Giraldus Cambrensis (Gerald of Wales) during his 1188 visit to Mynyw (modern St Davids), where he noted persistent rigorous practices traceable to foundational traditions.[2] [71] Documentary traces include ninth- and tenth-century references in Welsh charters and genealogies linking David to episcopal succession at Mynyw, while archaeological evidence from St Davids reveals early medieval stone carvings and church foundations indicative of sixth- to seventh-century Christian activity in the region, predating Norman influences.[16] These suggest a real individual around whom a cult coalesced rapidly, as evidenced by David's invocation in Irish hagiographies by the eighth century.[69] Critics, however, highlight vulnerabilities in this reconstruction. The absence of David's name in near-contemporary texts, such as Gildas's De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae (circa 540 CE), which chronicles British church figures amid Saxon incursions, undermines claims of his prominence as a national leader or synod convener.[40] Later vitae, including those by Giraldus and anonymous twelfth-century expansions, amplify Rhygyfarch's narrative with interpolations, potentially retrojecting eleventh-century ecclesiastical priorities—such as asserting metropolitan status for St Davids—onto a sixth-century context.[47] Some analyses propose David as a composite of multiple early Welsh ascetics, with biographical parallels to figures like Paulinus or Illtud drawn from shared folkloric topoi common in Insular saints' lives. Despite these reservations, outright dismissal of David's existence lacks support, as the sustained cult and institutional continuity at Mynyw imply a foundational historical personality rather than pure invention.[72]Scholarly Interpretations

Scholars concur that a historical figure underlying Saint David existed as a 6th-century monastic leader and bishop in southwestern Wales, founding the community at Mynyw (modern St David's) amid the fragmented post-Roman British landscape, though primary evidence is limited to later vitae and annals lacking contemporary corroboration.[34][2] The core of his biography derives from Rhygyfarch's Vita Sancti David, composed circa 1090, which blends oral traditions with invented elements to legitimize the see's authority, as evidenced by its chronological inconsistencies and miraculous interpolations unsupported by earlier records like Gildas's 6th-century writings.[34][31] David N. Dumville interprets the vitae as preserving a kernel of historicity, linking David to Gildas's correspondence critiquing overly austere monasticism and positing his death between 589 (Irish annals) and 601 (Annales Cambriae), rejecting hagiographical claims of a 147-year lifespan as fabrications.[31] He emphasizes David's role in instituting a rigorous rule—encompassing manual labor, vegetarianism, and water-only consumption, earning the epithet Aquaticus—as reflective of broader Celtic ascetic traditions rather than isolated legend, though without direct archaeological ties to Mynyw beyond the site's early Christian activity from the 5th-6th centuries.[31][34] Jonathan M. Wooding views David's portrayal in Rhygyfarch's text as authentically capturing 6th-century Welsh ecclesiastical reform, with his opposition to Pelagian remnants at synods like that at Brefi representing efforts to align British churches with orthodox continental practices amid isolation from Roman structures.[2] This interpretation underscores his function as a symbol of indigenous British resistance to external influences, later amplified in medieval Welsh poetry to forge national identity, yet grounded in the vitae’s depiction of communal self-sufficiency over episcopal hierarchy.[2][34] Genealogical claims, such as descent from regional chieftains via parents Sant and Non, are dismissed by most as retrospective inventions to elevate his status, paralleling patterns in other early Welsh saints' lives where kinship ties served proprietary church claims rather than verifiable descent.[31][34] While no peer-reviewed consensus denies his existence outright—given alignment with dated annals and Gildas's milieu—scholars caution against accepting unverified details like miraculous ground-raising or dove companionship as causal events, attributing them to hagiographic topoi common in Insular literature to inspire devotion.[31][2] Overall, interpretations frame David as emblematic of decentralized, ascetic Christianity in sub-Roman Britain, pivotal to the see's endurance against Viking raids and Norman impositions, yet his legacy remains more evidentiary in cultic persistence than biographical precision.[31][34]References

- https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Catholic_Encyclopedia_%281913%29/St._David