Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Abbot

View on Wikipedia

Abbot is an ecclesiastical title given to the head of an independent monastery for men in various Western Christian traditions. The name is derived from abba, the Aramaic form of the Hebrew ab, and means "father".[1] The female equivalent is abbess.

Origins

[edit]The title had its origin in the monasteries of Egypt and Syria, spread through the eastern Mediterranean, and soon became accepted generally in all languages as the designation of the head of a monastery. The word is derived from the Aramaic av meaning "father" or abba, meaning "my father" (it still has this meaning in contemporary Arabic: أب, Hebrew: אבא and Aramaic: ܐܒܐ) In the Septuagint, it was written as "abbas".[2] At first it was employed as a respectful title for any monk, but it was soon restricted by canon law to certain priestly superiors. At times it was applied to various priests, e.g. at the court of the Frankish monarchy the Abbas palatinus ("of the palace"') and Abbas castrensis ("of the camp") were chaplains to the Merovingian and Carolingian sovereigns' court and army respectively. The title of abbot came into fairly general use in western monastic orders whose members include priests.[3]

Monastic history

[edit]

An abbot (from Old English: abbod, abbad, from Latin: abbas ("father"), from Ancient Greek: ἀββᾶς (abbas), from Imperial Aramaic: אבא/ܐܒܐ ('abbā, "father"); compare German: Abt; French: abbé) is the head and chief governor of a community of monks, called also in the East hegumen or archimandrite.[3] The English version for a female monastic head is abbess.

Early history

[edit]In Egypt, the first home of monasticism, the jurisdiction of the abbot, or archimandrite, was but loosely defined. Sometimes he ruled over only one community, sometimes over several, each of which had its own abbot as well. Saint John Cassian speaks of an abbot of the Thebaid who had 500 monks under him. By the Rule of St Benedict, which, until the Cluniac reforms, was the norm in the West, the abbot has jurisdiction over only one community. The rule, as was inevitable, was subject to frequent violations; but it was not until the foundation of the Cluniac Order that the idea of a supreme abbot, exercising jurisdiction over all the houses of an order, was definitely recognised.[3]

Monks, as a rule, were laymen, nor at the outset was the abbot any exception. For the reception of the sacraments, and for other religious offices, the abbot and his monks were commanded to attend the nearest church. This rule proved inconvenient when a monastery was situated in a desert or at a distance from a city, and necessity compelled the ordination of some monks. This innovation was not introduced without a struggle, ecclesiastical dignity being regarded as inconsistent with the higher spiritual life, but, before the close of the 5th century, at least in the East, abbots seem almost universally to have become deacons, if not priests. The change spread more slowly in the West, where the office of abbot was commonly filled by laymen till the end of the 7th century. The ecclesiastical leadership exercised by abbots despite their frequent lay status is proved by their attendance and votes at ecclesiastical councils. Thus at the first Council of Constantinople, AD 448, 23 archimandrites or abbots sign, with 30 bishops.[3]

The second Council of Nicaea, AD 787, recognized the right of abbots to ordain their monks to the inferior orders[3] below the diaconate, a power usually reserved to bishops.

Abbots used to be subject to episcopal jurisdiction, and continued generally so, in fact, in the West till the 11th century. The Code of Justinian (lib. i. tit. iii. de Ep. leg. xl.) expressly subordinates the abbot to episcopal oversight. The first case recorded of the partial exemption of an abbot from episcopal control is that of Faustus, abbot of Lerins, at the council of Arles, AD 456; but the exorbitant claims and exactions of bishops, to which this repugnance to episcopal control is to be traced, far more than to the arrogance of abbots, rendered it increasingly frequent, and, in the 6th century, the practice of exempting religious houses partly or altogether from episcopal control, and making them responsible to the pope alone, received an impulse from Pope Gregory the Great. These exceptions, introduced with a good object, had grown into a widespread evil by the 12th century, virtually creating an imperium in imperio, and depriving the bishop of all authority over the chief centres of influence in his diocese.[3]

Later Middle Ages

[edit]In the 12th century, the abbots of Fulda claimed precedence of the archbishop of Cologne. Abbots more and more assumed almost episcopal state, and in defiance of the prohibition of early councils and the protests of St Bernard and others, adopted the episcopal insignia of mitre, ring, gloves and sandals.[3]

It has been maintained that the right to wear mitres was sometimes granted by the popes to abbots before the 11th century, but the documents on which this claim is based are not genuine (J. Braun, Liturgische Gewandung, p. 453). The first undoubted instance is the bull by which Alexander II in 1063 granted the use of the mitre to Egelsinus, abbot of the monastery of St Augustine at Canterbury. The mitred abbots in England were those of Abingdon, St Alban's, Bardney, Battle, Bury St Edmunds, St Augustine's Canterbury, Colchester, Croyland, Evesham, Glastonbury, Gloucester, St Benet's Hulme, Hyde, Malmesbury, Peterborough, Ramsey, Reading, Selby, Shrewsbury, Tavistock, Thorney, Westminster, Winchcombe, and St Mary's York.[4] Of these the precedence was yielded to the abbot of Glastonbury, until in AD 1154 Adrian IV (Nicholas Breakspear) granted it to the abbot of St Alban's, in which monastery he had been brought up. Next after the abbot of St Alban's ranked the abbot of Westminster and then Ramsey.[5] Elsewhere, the mitred abbots that sat in the Estates of Scotland were of Arbroath, Cambuskenneth, Coupar Angus, Dunfermline, Holyrood, Iona, Kelso, Kilwinning, Kinloss, Lindores, Paisley, Melrose, Scone, St Andrews Priory and Sweetheart.[6] To distinguish abbots from bishops, it was ordained that their mitre should be made of less costly materials, and should not be ornamented with gold, a rule which was soon entirely disregarded, and that the crook of their pastoral staff (the crosier) should turn inwards instead of outwards, indicating that their jurisdiction was limited to their own house.[3]

The adoption of certain episcopal insignia (pontificalia) by abbots was followed by an encroachment on episcopal functions, which had to be specially but ineffectually guarded against by the Lateran council, AD 1123. In the East abbots, if in priests' orders and with the consent of the bishop, were, as we have seen, permitted by the second Nicene council, AD 787, to confer the tonsure and admit to the order of reader; but gradually abbots, in the West also, advanced higher claims, until we find them in AD 1489 permitted by Innocent IV to confer both the subdiaconate and diaconate. Of course, they always and everywhere had the power of admitting their own monks and vesting them with the religious habit.[3]

The power of the abbot was paternal but absolute, limited, however, by the canon law. One of the main goals of monasticism was the purgation of self and selfishness, and obedience was seen as a path to that perfection. It was sacred duty to execute the abbot's orders, and even to act without his orders was sometimes considered a transgression. Examples among the Egyptian monks of this submission to the commands of the superiors, exalted into a virtue by those who regarded the entire crushing of the individual will as a goal, are detailed by Cassian and others, e.g. a monk watering a dry stick, day after day, for months, or endeavoring to remove a huge rock immensely exceeding his powers.[3]

Appointments

[edit]When a vacancy occurred, the bishop of the diocese chose the abbot out of the monks of the monastery, but the right of election was transferred by jurisdiction to the monks themselves, reserving to the bishop the confirmation of the election and the benediction of the new abbot. In abbeys exempt from the archbishop's diocesan jurisdiction, the confirmation and benediction had to be conferred by the pope in person, the house being taxed with the expenses of the new abbot's journey to Rome. It was necessary that an abbot should be at least 30 years of age, of legitimate birth, a monk of the house for at least 10 years,[2] unless it furnished no suitable candidate, when a liberty was allowed of electing from another monastery, well instructed himself, and able to instruct others, one also who had learned how to command by having practised obedience.[3] In some exceptional cases an abbot was allowed to name his own successor. Cassian speaks of an abbot in Egypt doing this; and in later times we have another example in the case of St Bruno. Popes and sovereigns gradually encroached on the rights of the monks, until in Italy the pope had usurped the nomination of all abbots, and the king in France, with the exception of Cluny, Premontré and other houses, chiefs of their order. The election was for life, unless the abbot was canonically deprived by the chiefs of his order, or when he was directly subject to them, by the pope or the bishop, and also in England it was for a term of 8–12 years.[2]

The ceremony of the formal admission of a Benedictine abbot in medieval times is thus prescribed by the consuetudinary of Abingdon. The newly elected abbot was to put off his shoes at the door of the church, and proceed barefoot to meet the members of the house advancing in a procession. After proceeding up the nave, he was to kneel and pray at the topmost step of the entrance of the choir, into which he was to be introduced by the bishop or his commissary, and placed in his stall. The monks, then kneeling, gave him the kiss of peace on the hand, and rising, on the mouth, the abbot holding his staff of office. He then put on his shoes in the vestry, and a chapter was held, and the bishop or his delegate preached a suitable sermon.[3]

General information

[edit]Before the late modern era, the abbot was treated with the utmost reverence by the brethren of his house. When he appeared either in church or chapter all present rose and bowed. His letters were received kneeling, as were those of the pope and the king. No monk might sit in his presence, or leave it, without his permission, reflecting the hierarchical etiquette of families and society. The highest place was assigned to him, both in church and at table. In the East he was commanded to eat with the other monks. In the West, the Rule of St Benedict appointed him a separate table, at which he might entertain guests and strangers. Because this permission opened the door to luxurious living, Synods of Aachen decreed that the abbot should dine in the refectory, and be content with the ordinary fare of the monks, unless he had to entertain a guest. These ordinances proved, however, generally ineffective to secure strictness of diet, and contemporaneous literature abounds with satirical remarks and complaints concerning the inordinate extravagance of the tables of the abbots. When the abbot condescended to dine in the refectory, his chaplains waited upon him with the dishes, a servant, if necessary, assisting them. When abbots dined in their own private hall, the Rule of St Benedict charged them to invite their monks to their table, provided there was room, on which occasions the guests were to abstain from quarrels, slanderous talk and idle gossiping.[3]

The ordinary attire of the abbot was according to rule to be the same as that of the monks. But by the 10th century the rule was commonly set aside, and we find frequent complaints of abbots dressing in silk, and adopting sumptuous attire. Some even laid aside the monastic habit altogether, and assumed a secular dress. With the increase of wealth and power, abbots had lost much of their special religious character, and become great lords, chiefly distinguished from lay lords by celibacy. Thus we hear of abbots going out to hunt, with their men carrying bows and arrows; keeping horses, dogs and huntsmen; and special mention is made of an abbot of Leicester [citation needed], c. 1360, who was the most skilled of all the nobility in hare hunting. In magnificence of equipage and retinue the abbots vied with the first nobles of the realm. They rode on mules with gilded bridles, rich saddles and housings, carrying hawks on their wrist, followed by an immense train of attendants. The bells of the churches were rung as they passed. They associated on equal terms with laymen of the highest distinction, and shared all their pleasures and pursuits.[3] This rank and power was, however, often used most beneficially. For instance, we read of Richard Whiting, the last abbot of Glastonbury, judicially murdered by Henry VIII, that his house was a kind of well-ordered court, where as many as 300 sons of noblemen and gentlemen, who had been sent to him for virtuous education, had been brought up, besides others of a lesser rank, whom he fitted for the universities. His table, attendance and officers were an honour to the nation. He would entertain as many as 500 persons of rank at one time, besides relieving the poor of the vicinity twice a week. He had his country houses and fisheries, and when he travelled to attend parliament his retinue amounted to upwards of 100 persons. The abbots of Cluny and Vendôme were, by virtue of their office, cardinals of the Roman church.[3]

In the process of time, the title abbot was extended to clerics who had no connection with the monastic system, as to the principal of a body of parochial clergy; and under the Carolingians to the chief chaplain of the king, Abbas Curiae, or military chaplain of the emperor, Abbas Castrensis. It even came to be adopted by purely secular officials. Thus the chief magistrate of the republic at Genoa was called Abbas Populi.[3]

Lay abbots (M. Lat. defensores, abbacomites, abbates laici, abbates milites, abbates saeculares or irreligiosi, abbatiarii, or sometimes simply abbates) were the outcome of the growth of the feudal system from the 8th century onwards. The practice of commendation, by which—to meet a contemporary emergency—the revenues of the community were handed over to a lay lord, in return for his protection, early suggested to the emperors and kings the expedient of rewarding their warriors with rich abbeys held in commendam.[3]

During the Carolingian epoch, the custom grew up of granting these as regular heritable fiefs or benefices, and by the 10th century, before the great Cluniac reform, the system was firmly established. Even the abbey of St Denis was held in commendam by Hugh Capet. The example of the kings was followed by the feudal nobles, sometimes by making a temporary concession permanent, sometimes without any form of commendation whatever. In England the abuse was rife in the 8th century, as may be gathered from the acts of the council of Cloveshoe. These lay abbacies were not merely a question of overlordship, but implied the concentration in lay hands of all the rights, immunities and jurisdiction of the foundations, i.e. the more or less complete secularization of spiritual institutions. The lay abbot took his recognized rank in the feudal hierarchy, and was free to dispose of his fief as in the case of any other. The enfeoffment of abbeys differed in form and degree. Sometimes the monks were directly subject to the lay abbot; sometimes he appointed a substitute to perform the spiritual functions, known usually as dean (decanus), but also as abbot (abbas legitimus, monasticus, regularis).[3]

When the great reform of the 11th century had put an end to the direct jurisdiction of the lay abbots, the honorary title of abbot continued to be held by certain of the great feudal families, as late as the 13th century and later, with the head of the community retaining the title of dean. The connection of the lesser lay abbots with the abbeys, especially in the south of France, lasted longer; and certain feudal families retained the title of abbés chevaliers (Latin: abbates milites) for centuries, together with certain rights over the abbey lands or revenues. The abuse was not confined to the West. John, patriarch of Antioch at the beginning of the 12th century, informs us that in his time most monasteries had been handed over to laymen, beneficiarii, for life, or for part of their lives, by the emperors.[3]

Giraldus Cambrensis reported (Itinerary, ii.iv) the common customs of lay abbots in the late 12th-century Church of Wales:

for a bad custom has prevailed amongst the clergy, of appointing the most powerful people of a parish stewards, or, rather, patrons, of their churches; who, in process of time, from a desire of gain, have usurped the whole right, appropriating to their own use the possession of all the lands, leaving only to the clergy the altars, with their tenths and oblations, and assigning even these to their sons and relations in the church. Such defenders, or rather destroyers, of the church, have caused themselves to be called abbots, and presumed to attribute to themselves a title, as well as estates, to which they have no just claim.

In conventual cathedrals, where the bishop occupied the place of the abbot, the functions usually devolving on the superior of the monastery were performed by a prior.

Modern practices

[edit]In the Roman Catholic Church and Evangelical-Lutheran Churches, abbots continue to be elected by the monks of an abbey to lead them as their religious superior in those orders and monasteries that make use of the term (some orders of monks, as the Carthusians for instance, have only priors).[7] In Catholicism, a monastery must have been granted the status of an abbey by the pope,[8] and such monasteries are normally raised to this level after showing a degree of stability—a certain number of monks in vows, a certain number of years of establishment, a certain firmness to the foundation in economic, vocational and legal aspects. Prior to this, the monastery would be a mere priory, headed by a prior who acts as superior but without the same degree of legal authority that an abbot has.

The abbot is chosen by the monks from among the fully professed monks. Once chosen, he must request blessing: the blessing of an abbot is celebrated by the bishop in whose diocese the monastery is or, with his permission, another abbot or bishop. The ceremony of such a blessing is similar in some aspects to the consecration of a bishop, with the new abbot being presented with the mitre, the ring, and the crosier as symbols of office and receiving the laying on of hands and blessing from the celebrant. Though the ceremony installs the new abbot into a position of legal authority, it does not confer further sacramental authority- it is not a further degree of Holy Orders (although some abbots have been ordained to the episcopacy).

Once he has received this blessing, the abbot not only becomes father of his monks in a spiritual sense, but their major superior under canon law, and has the additional authority to confer the ministries of acolyte and lector (formerly, he could confer the minor orders, which are not sacraments, that these ministries have replaced). The abbey is a species of "exempt religious" in that it is, for the most part, answerable to the pope, or to the abbot primate, rather than to the local bishop.

The abbot wears the same habit as his fellow monks, though by tradition he adds to it a pectoral cross.

Territorial abbots follow all of the above, but in addition must receive a mandate of authority from the pope over the territory around the monastery for which they are responsible.

Abbatial hierarchy

[edit]In some monastic families, there is a hierarchy of precedence or authority among abbots. In some cases, this is the result of an abbey being considered the "mother" of several "daughter" abbeys founded as dependent priories of the "mother". In other cases, abbeys have affiliated in networks known as "congregations". Some monastic families recognize one abbey as the motherhouse of the entire order.

- The abbot of Sant'Anselmo di Aventino, in Rome, is styled the "abbot primate", and is acknowledged the senior abbot for the Order of Saint Benedict.

- An abbot-president is the head of a congregation (federation) of abbeys within the Order of Saint Benedict (for instance, the English Congregation, the American-Cassinese Congregation, etc.), or of the Cistercians

- An archabbot is the head of some monasteries which are the motherhouses of other monasteries (for instance, Saint Vincent Archabbey, Latrobe, Pennsylvania)

- Mauro-Giuseppe Lepori OCist is the current abbot-general of the Cistercians of the Common Observance.

Modern abbots not as superior

[edit]The title abbé (French; Ital. abate), as commonly used in the Catholic Church on the European continent, is the equivalent of the English "Father" (parallel etymology), being loosely applied to all who have received the tonsure. This use of the title is said to have originated in the right conceded to the king of France, by the concordat between Pope Leo X and Francis I (1516), to appoint commendatory abbots (abbés commendataires) to most of the abbeys in France. The expectation of obtaining these sinecures drew young men towards the church in considerable numbers, and the class of abbés so formed – abbés de cour they were sometimes called, and sometimes (ironically) abbés de sainte espérance ("abbés of holy hope; or in a jeu de mots, "of St. Hope") – came to hold a recognized position. The connection many of them had with the church was of the slenderest kind, consisting mainly in adopting the title of abbé, after a remarkably moderate course of theological study, practising celibacy and wearing distinctive dress, a short dark-violet coat with narrow collar. Being men of presumed learning and undoubted leisure, many of the class found admission to the houses of the French nobility as tutors or advisers. Nearly every great family had its abbé. The class did not survive the Revolution; but the courtesy title of abbé, having long lost all connection in people's minds with any special ecclesiastical function, remained as a convenient general term applicable to any clergyman.

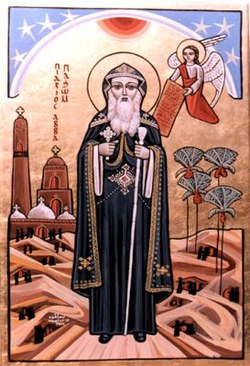

Eastern Christian

[edit]In the Eastern Orthodox and Eastern Catholic Churches, the abbot is referred to as the hegumen. The Superior of a monastery of nuns is called the Hēguménē. The title of archimandrite (literally the head of the enclosure) used to mean something similar.

In the East[clarification needed], the principle set forth in the Corpus Juris Civilis still applies, whereby most abbots are immediately subject to the local bishop. Those monasteries which enjoy the status of being stauropegic will be subject only to a primate or his Synod of Bishops and not the local bishop.

Honorary and other uses of the title

[edit]Although currently in the Western Church the title "abbot" is given only abbots of monasteries, the title archimandrite is given to "monastics" (i.e., celibate) priests in the East, even when not attached to a monastery, as an honor for service, similar to the title of monsignor in the Latin Church of the Catholic Church. In the Eastern Orthodox Church, only monastics are permitted to be elevated to the rank of archimandrite. Married priests are elevated to the parallel rank of Archpriest or Protopresbyter. Normally there are no celibate priests who are not monastics in the Orthodox Church, with the exception of married priests who have been widowed. Since the time of Catherine II the ranks of Abbot and Archimandrite have been given as honorary titles in the Russian Church, and may be given to any monastic, even if he does not in fact serve as the superior of a monastery. In Greek practice the title or function of Abbot corresponds to a person who serves as the head of a monastery, although the title of the Archimandrite may be given to any celibate priest who could serve as the head of a monastery.

In the German Evangelical Church, the German title of Abt (abbot) is sometimes bestowed, like the French abbé, as an honorary distinction, and additionally designates the heads of monasteries, with a number of these that accepted the Evangelical-Lutheran faith at the time of the Reformation. Of these the most noteworthy is Loccum Abbey in Hanover, founded as a Cistercian house in 1163 by Count Wilbrand of Hallermund, and Lutheranised in 1593. The abbot of Loccum, who still carries a pastoral staff, takes precedence over all the clergy of Hanover, and was ex officio a member of the consistory of the kingdom. The governing body of the abbey consists of the abbot, prior and the "convent", or community, of Stiftsherren (canons).

With respect to Anglicanism, in the Church of England, the Bishop of Norwich, by royal decree given by Henry VIII, also holds the honorary title of "Abbot of St. Benet." This title hails back to England's separation from the See of Rome, when King Henry, as supreme head of the newly independent church, took over all of the monasteries, mainly for their possessions, except for St. Benet, which he spared because the abbot and his monks possessed no wealth, and lived like simple beggars, deposing the incumbent Bishop of Norwich and seating the abbot in his place, thus the dual title still held to this day. Additionally, at the enthronement of the Archbishop of Canterbury, there is a threefold enthronement, once in the throne the chancel as the diocesan bishop of Canterbury, once in the Chair of St. Augustine as the Primate of All England, and then once in the chapter-house as Titular Abbot of Canterbury.

There are several Benedictine abbeys throughout the Anglican Communion. Most of them have mitred abbots.

Abbots in art and literature

[edit]

"The Abbot" is one of the archetypes traditionally illustrated in scenes of Danse Macabre.

The lives of numerous abbots make up a significant contribution to Christian hagiography, one of the most well-known being the Life of St. Benedict of Nursia by St. Gregory the Great.

During the years 1106–1107 AD, Daniel, a Russian Orthodox abbot, made a pilgrimage to the Holy Land and recorded his experiences. His diary was much-read throughout Russia, and at least seventy-five manuscript copies survive. Saint Joseph, Abbot of Volokolamsk, Russia (1439–1515), wrote a number of influential works against heresy, and about monastic and liturgical discipline, and Christian philanthropy.

In the Tales of Redwall series, the creatures of Redwall are led by an abbot or abbess. These "abbots" are appointed by the brothers and sisters of Redwall to serve as a superior and provide paternal care, much like real abbots.

"The Abbot" was a nickname of RZA from the Wu-Tang Clan.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Thomas Oesterreich, Abbot, in The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907.

- ^ a b c "Abbey Austin". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. I: A–Ak – Bayes (15th ed.). Chicago, IL: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 2010. pp. 12. ISBN 978-1-59339-837-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Venables & Phillips 1911.

- ^ Government in Church and State Archived 23 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine from University of Wisconsin-Madison retrieved 15 June 2013

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1911). . Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 12. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Cowan, Ian B.; Easson, David E. (1976), Medieval Religious Houses: Scotland With an Appendix on the Houses in the Isle of Man (2nd ed.), London and New York: Longman, ISBN 0-582-12069-1 pp. 67–97

- ^ "Klösterliche Gemeinschaft" (in German). Amelungsborn Abbey. 2025. Retrieved 23 October 2025.

- ^ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Abbot". www.newadvent.org. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

References

[edit]- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Venables, Edmund; Phillips, Walter Alison (1911). "Abbot". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). pp. 23–25.