Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Mechanical equilibrium

View on Wikipedia

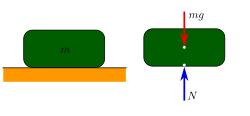

In classical mechanics, a particle is in mechanical equilibrium if the net force on that particle is zero.[1]: 39 By extension, a physical system made up of many parts is in mechanical equilibrium if the net force on each of its individual parts is zero.[1]: 45–46 [2]

In addition to defining mechanical equilibrium in terms of force, there are many alternative definitions for mechanical equilibrium which are all mathematically equivalent.

- In terms of momentum, a system is in equilibrium if the momentum of its parts is all constant.

- In terms of velocity, the system is in equilibrium if velocity is constant.

- In a rotational mechanical equilibrium the angular momentum of the object is conserved and the net torque is zero.[2]

More generally in conservative systems, equilibrium is established at a point in configuration space where the gradient of the potential energy with respect to the generalized coordinates is zero.

If a particle in equilibrium has zero velocity, that particle is in static equilibrium.[3][4] Since all particles in equilibrium have constant velocity, it is always possible to find an inertial reference frame in which the particle is stationary with respect to the frame.

Stability

[edit]An important property of systems at mechanical equilibrium is their stability.

Potential energy stability test

[edit]In a function which describes the system's potential energy, the system's equilibria can be determined using calculus. A system is in mechanical equilibrium at the critical points of the function describing the system's potential energy. These points can be located using the fact that the derivative of the function is zero at these points. To determine whether or not the system is stable or unstable, the second derivative test is applied. With denoting the static equation of motion of a system with a single degree of freedom the following calculations can be performed:

- Second derivative < 0

- The potential energy is at a local maximum, which means that the system is in an unstable equilibrium state. If the system is displaced an arbitrarily small distance from the equilibrium state, the forces of the system cause it to move even farther away.

- Second derivative > 0

- The potential energy is at a local minimum. This is a stable equilibrium. The response to a small perturbation is forces that tend to restore the equilibrium. If more than one stable equilibrium state is possible for a system, any equilibria whose potential energy is higher than the absolute minimum represent metastable states.

- Second derivative = 0

- The state is neutral to the lowest order and nearly remains in equilibrium if displaced a small amount. To investigate the precise stability of the system, higher order derivatives can be examined. The state is unstable if the lowest nonzero derivative is of odd order or has a negative value, stable if the lowest nonzero derivative is both of even order and has a positive value. If all derivatives are zero then it is impossible to derive any conclusions from the derivatives alone. For example, the function (defined as 0 in x=0) has all derivatives equal to zero. At the same time, this function has a local minimum in x=0, so it is a stable equilibrium. If this function is multiplied by the Sign function, all derivatives will still be zero but it will become an unstable equilibrium.

- Function is locally constant

- In a truly neutral state the energy does not vary and the state of equilibrium has a finite width. This is sometimes referred to as a state that is marginally stable, or in a state of indifference, or astable equilibrium.

When considering more than one dimension, it is possible to get different results in different directions, for example stability with respect to displacements in the x-direction but instability in the y-direction, a case known as a saddle point. Generally an equilibrium is only referred to as stable if it is stable in all directions.

Statically indeterminate system

[edit]Sometimes the equilibrium equations – force and moment equilibrium conditions – are insufficient to determine the forces and reactions. Such a situation is described as statically indeterminate.

Statically indeterminate situations can often be solved by using information from outside the standard equilibrium equations.

Examples

[edit]A stationary object (or set of objects) is in "static equilibrium," which is a special case of mechanical equilibrium. A paperweight on a desk is an example of static equilibrium. Other examples include a rock balance sculpture, or a stack of blocks in the game of Jenga, so long as the sculpture or stack of blocks is not in the state of collapsing.

Objects in motion can also be in equilibrium. A child sliding down a slide at constant speed would be in mechanical equilibrium, but not in static equilibrium (in the reference frame of the earth or slide).

Another example of mechanical equilibrium is a person pressing a spring to a defined point. He or she can push it to an arbitrary point and hold it there, at which point the compressive load and the spring reaction are equal. In this state the system is in mechanical equilibrium. When the compressive force is removed the spring returns to its original state.

The minimal number of static equilibria of homogeneous, convex bodies (when resting under gravity on a horizontal surface) is of special interest. In the planar case, the minimal number is 4, while in three dimensions one can build an object with just one stable and one unstable balance point.[5] Such an object is called a gömböc.

See also

[edit]Notes and references

[edit]- ^ a b John L Synge & Byron A Griffith (1949). Principles of Mechanics (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- ^ a b Beer FP, Johnston ER, Mazurek DF, Cornell PJ, and Eisenberg, ER (2009). Vector Mechanics for Engineers: Statics and Dynamics (9th ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 158.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Herbert Charles Corben & Philip Stehle (1994). Classical Mechanics (Reprint of 1960 second ed.). Courier Dover Publications. p. 113. ISBN 0-486-68063-0.

- ^ Lakshmana C. Rao; J. Lakshminarasimhan; Raju Sethuraman; Srinivasan M. Sivakumar (2004). Engineering Mechanics. PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd. p. 6. ISBN 81-203-2189-8.

- ^ "Mathematics". Gömböc. 2021. Retrieved 12 November 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- Marion JB and Thornton ST. (1995) Classical Dynamics of Particles and Systems. Fourth Edition, Harcourt Brace & Company.