Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Substantive equality

View on Wikipedia

The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (October 2018) |

Substantive equality is a substantive law on human rights that is concerned with equality of outcome for disadvantaged and marginalized people and groups and generally all subgroups in society.[1][2] Scholars define substantive equality as an output or outcome of the policies, procedures, and practices used by nation states and private actors in addressing and preventing systemic discrimination.[3][2][4]

Substantive equality recognizes that the law must take elements such as discrimination, marginalization, and unequal distribution into account in order to achieve equal results for basic human rights, and access to goods and services.[2] Substantive equality is primarily achieved by implementing special measures[5] in order to assist or advance the lives of disadvantaged individuals. Such measures are aimed at ensuring that they are given the same outcomes as everyone else.[1]

Substantive equality is distinct from formal equal opportunity, which ensures equal opportunity based on meritocracy, but not equal outcomes for subgroups.[6]

Substantive equality can include affirmative action and quota systems including gender quotas and racial quotas.

Definition

[edit]Substantive equality has been criticized for not having a clear definition. Sandra Fredman has argued that substantive equality should be viewed as a four-dimensional concept of recognition, redistribution, participation, and transformation.[7] The redistributive dimension seeks to redress disadvantage through affirmative action, while the recognition dimension aims to promote the right to equality and identify the stereotypes, prejudice and violence that affect marginalized and disadvantaged individuals.[7] The participative dimension uses Ely's insight[clarification needed] to argue that judicial review must compensate marginalized individuals for their lack of political power.[8][7] The participative dimension may also implement positive duties to ensure that all those affected by discrimination can be active members of society.[7] Lastly, the transformative dimension recognizes that equality is not achieved through equal treatment and that the societal structures which reinforce disadvantage and discrimination must be modified or transformed to accommodate difference.[7] The transformative dimension may use both positive and negative duties to redress disadvantage.[7] Fredman advocates for a four-dimensional approach to substantive equality as a way to address the criticisms and limitations it faces due to the lack of agreement on its definition by scholars.[7]

History

[edit]

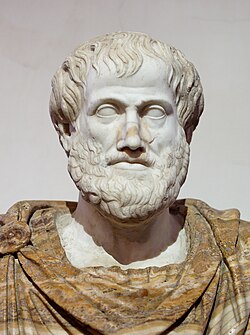

Aristotle was the first philosopher to articulate the connection between equality and justice. Aristotle believed equals were to be treated alike and unequals in an unlike manner.[9] Aristotle's notion of equality influenced the conception of formal equality in western jurisprudence. Formal equality advocates for the neutral treatment of all people based on the norms of the dominant group in society.[4] While first-wave feminism mostly advocated for formal equality, second-wave feminism promoted substantive equality.[10] During the late 20th century, substantive equality originated in opposition to formal equality.[9] This approach was inspired by early landmark constitutional cases in the United States, which broke away from formal approaches to equality in favor of a more substantive process. For example, in Brown v. Board of Education (1954) the US Supreme Court deemed it unlawful to segregate children's access to education on the basis of race.[9] This case was influential in transforming US anti-discrimination laws as it sought equitable outcomes for African Americans.[9] The substantive approach rejects earlier notions that claimed social, political, economic, and historical differences were a legitimate justification for the differential treatment of marginalised and disadvantaged groups in society.[11]

The substantive approach to equality is entrenched in human rights treaties, laws, and jurisprudence, which is then adopted and implemented by nation states and private actors. This is present in Article 14 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), which states that:

The enjoyment of the rights and freedoms set forth in this Convention shall be secured without discrimination on any ground such as sex, race, color, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, association with a national minority, property, birth or other status.[7]: 275

Article 14 prohibits discrimination in all aspects of public life on the basis of nominated attributes. Although Article 14 fails to mention discrimination on the basis of sexuality, age, and disability, recent developments in case law have shown that these grounds are illustrative but not exhaustive and can extend to include these factors.[7] Nation states that have signed and ratified the ECHR have an obligation to enact legislation preventing discrimination by using special measures to protect and advance the lives of disadvantaged and marginalized individuals in society. Article 1(4) of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD) defines special measures as, "securing adequate advancement of certain racial or ethnic groups or individuals requiring such protection as may be necessary in order to ensure such groups or individuals equal enjoyment or exercise of human rights and fundamental freedoms shall not be deemed racial discrimination".[1]: 9

These two articles are the fundamental principles that define the practice of substantive equality. Failure to enact substantive legislation by signatories may result in heavy sanctions and scrutiny from the international community.

Criticism

[edit]Substantive equality has been criticized in the past for its vague definition and its tenuous ability to help combat discrimination for marginalized and disadvantaged individuals.[7] Scholars have argued that the meaning of substantive equality remains elusive, which makes it difficult to implement change due to the lack of consensus. The meaning of equality itself has been labeled as subjective as there are too many conflicting opinions within society to find one underlying definition.[7][11] Substantive equality has also been criticized for its lack of ability to protect individuals from discrimination and for placing too much emphasis on compensation rather than preventing discrimination from occurring.[12] Welfare and affirmative action programs have been recognized as areas of concern, as the way in which they are delivered can be discriminatory in nature because they can reinforce and perpetuate stigmas that are held within society.[7]

By country

[edit]Australia

[edit]Anti-discrimination laws in Australia are enacted by commonwealth, state, and territory parliaments and are then interpreted by courts and tribunals.[12] These laws are covered under the following four key commonwealth statutes: the Racial Discrimination Act (1975), Sex Discrimination Act (1984), Disability Discrimination Act (1992), and Age Discrimination Act (2004).[12]

All Australian states and territories have enacted a statute (variously called the anti-discrimination act) which prohibits all forms of discrimination in public life on the basis of nominated attributes identified in Article 26 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).[12] This statute makes it unlawful to discriminate against others both directly (when a person is treated unfairly) or indirectly (when something is fair in form but discriminatory in practice).[12] For example, indirect discrimination may occur in the workforce when employees are expected to comply with a condition or requirement of the job (i.e. height restrictions) but are unable to meet them because they are unreasonable or unfair.[13][12] Compliance with anti-discrimination laws is enforceable through civil proceedings, which may result in heavy fines or penalties. These laws have been criticized for focusing too much on compensation and not enough on preventing discrimination from occurring.[12]

These anti-discrimination laws use substantive measures by promoting equal outcomes and implementing special measures identified in ICERD Article 1(4) to overcome discrimination. Private actors, organizations, and governments use special measures in the form of affirmative action programs to ensure disadvantaged individuals are given the same outcomes as everyone else. The Australian government has identified women, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, people with disabilities, and non-English speaking migrants as high-priority groups for the administration of special measures programs.[2] The Northern Territory government has recognized Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, and people with disabilities as high-priority groups for their affirmative action programs by focusing on employment outcomes and employment representations for these groups.[2] These programs use substantive measures as they acknowledge that there is a need to treat people differently by prioritizing these groups as they have been unfairly discriminated upon. For example, in 2011 the Australian Bureau of Statistics reported that Indigenous peoples were 3 times more likely to be unemployed than non-indigenous people.[14] This demonstrates the need for affirmative action policies to protect and advance the lives of Aboriginal people, as they do not have the same outcomes of employment.[14]

Brazil

[edit]Issues about substantive equality have been raised about the skin color of runway models at the São Paulo Fashion Week and in 2009 quotas requiring that at least 10 percent of models be "black or indigenous" were imposed as a substantive way to counteract a "bias towards white models", according to one account.[15]

Canada

[edit]The case of R v Kapp was instrumental in shifting the focus from formal equality to substantive equality in Canadian jurisprudence. In 1998, the Canadian government granted a communal fishing license exclusively to members of three Aboriginal bands for a period of 24 hours in the Fraser river that allowed them the right to fish and sell their catch.[16] The appellants consisted mainly of a group of non-Aboriginal commercial fishermen who protested against the license and were subsequently charged with fishing at a prohibited time.[16] The fishermen argued that they were being unfairly discriminated against on the basis of race under section 15(1) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.[16] However, the Crown upheld the decision that the government did not violate section 15 of the charter,[16] and found that decision could not be discriminatory as section 15(1) and 15(2) work together to prevent discrimination and protect vulnerable individuals in society.[17] Section 15(1) aims to prevent discrimination against marginalized and disadvantaged groups, while section 15(2) aims to combat discrimination through affirmative action.[17] The Crown dismissed the appeal as under section 15(2) the Government has the power to implement affirmative action programs in order to advance the aboriginal bands access to jobs and resources.[18] The law can be understood as using substantive measures in R v Kapp as it recognizes that equal treatment (formal equal opportunity) does not result in the same opportunities across groups.[16][17] Instead, the law acknowledged that substantive equality is necessary to ensure the development of disadvantaged and marginalized individual's access to equality of outcomes.

European Union

[edit]The substantive equality embraced by Court of Justice of the European Union focuses on equality of outcomes for group characteristics and group outcomes.[6]

New Zealand

[edit]The case of Z v Z highlighted the issues with equal sharing of relationship property at the end of a relationship. In this case, the couple had been married for 28 years.[19] During this time the primary caregiver Mrs Z gave up her career to care for the couple's children.[19] At the end of the relationship, the couple had a property valued at NZ$900,000. Mr Z was on a salary of over $300,000 per annum, while Mrs Z received $7,000 in assistance from the government.[19] In Z v Z, the court failed to protect the primary caregiver by not taking into account her future earning capacity and her past sacrifices.[19] The Property (relationships) Amendment Act (2001) was introduced to rectify the problems of equal sharing highlighted in Z v Z.[19] The property act uses substantive equality to recognize that equal treatment can lead to disadvantage. The act recognizes the impact relationships can have on the earning capacities of individuals and it aims to place them in more substantive position at the end of the relationship.[19] However, the property act has been criticized for its ability to achieve substantive equality, as it does not state how economic disparity should be quantified.[19] Scholars have argued that it does not protect the most vulnerable as it is skewed towards relationships with high incomes because it is more difficult to establish an economic disparity in lower income cases.[19]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Cusack, Simone; Ball, Rachel (July 2009). Eliminating Discrimination and Ensuring Substantive Equality (PDF) (Report). Public Interest Law Clearing House and Human Rights Law Resource Centre Ltd. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-06-06. Retrieved 2024-03-27.

- ^ a b c d e "What is substantive equality?" (PDF). Equal Opportunity Commission, Government of Western Australia. November 2014. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- ^ "systematic discrimination". Archived from the original on 2019-01-19. Retrieved 2018-11-20.

- ^ a b Mitchell, Ben (2015). Process Equality, Substantive Equality and Recognising Disadvantage Constitutional Equality Law. Irish Jurist. 53: 36-57.

- ^ special measures

- ^ a b De Vos, Marc (2020). "The European Court of Justice and the march towards substantive equality in European Union anti-discrimination law". International Journal of Discrimination and the Law. 20 (1): 62–87. doi:10.1177/1358229120927947.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Fredman, Sandra (2016-04-16). "Emerging from the Shadows: Substantive Equality and Article 14 of the European Convention on Human Rights" (PDF). Human Rights Law Review. 16 (2): 273–301. doi:10.1093/hrlr/ngw001. ISSN 1461-7781. S2CID 148303122. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-02-12.

- ^ Ely, John Hart (1980). Democracy and distrust : a theory of judicial review. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674196360. OCLC 5333737.

- ^ a b c d Goonesekere, Savitri W.E (2011). The Concept of Substantive Equality and Gender in South East Asia. United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women.

- ^ Whelehan, Imelda (1 June 1995). Modern Feminist Thought: From the Second Wave to 'Post-Feminism'. Edinburgh University Press. doi:10.1515/9780748632084. ISBN 978-0-7486-3208-4.

- ^ a b Law commission of Ontario (2012). Principles for the Law as it Affects Persons with Disabilities. Law commission of Ontario. ISBN 978-1-926661-38-4

- ^ a b c d e f g Rees, Neil; Rice, Simon; Allen, Dominique (2018). Australian anti-discrimination and equal opportunity law. Federation Press. ISBN 9781760021559. OCLC 1005961080.

- ^ indirect discrimination

- ^ a b Dillon Sarah, Nissim, Rivkah (2015). "Targeted Recruitment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People: a Guideline for Employers". Australian Human Rights Commission. ISBN 978-1-921449-75-8

- ^ "Brazil fashion week goes equal opportunity". The Daily Telegraph. June 20, 2009. Retrieved 2011-09-08.

- ^ a b c d e Moreau, Sophia (2009). "R. V. Kapp: New Directions for Section 15" (PDF). Ottawa Law Review. 40 (2): 283–299.

- ^ a b c TREMBLAY, LUC B. (2012). "Promoting Equality and Combating Discrimination Through Affirmative Action: The Same Challenge? Questioning the Canadian Substantive Equality Paradigm". The American Journal of Comparative Law. 60 (1): 181–204. doi:10.5131/AJCL.2011.0025. JSTOR 23251953.

- ^ Richez, Emmanuelle (2013). "The Case of Canada". Australian Indigenous Law Review. 17 (2): 26–46. JSTOR 26423266.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Garland, Fae (2014-11-01). "Section 15 Property (Relationships) Act 1976: Compensation, Substantive Equality and Empirical Realities: English". New Zealand Law Review. 2014 (3): 355–381. ISSN 1173-5864.