Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

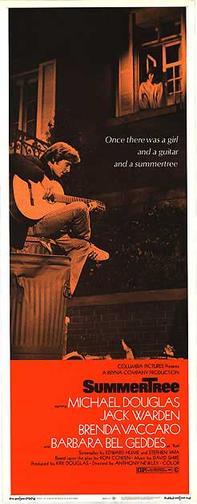

Summertree

View on Wikipedia| Summertree | |

|---|---|

Movie Poster | |

| Directed by | Anthony Newley |

| Screenplay by | |

| Based on | Summertree by Ron Cowen |

| Produced by | Kirk Douglas |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Richard C. Glouner |

| Edited by | Maury Winetrobe |

| Music by | David Shire |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 89 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

Summertree is a 1971 American drama film directed by Anthony Newley, about a young man who drops out of university, falls in love with an older married woman, and contemplates dodging the draft to avoid serving in the Vietnam War. The screenplay was written by Edward Hume and Stephen Yafa, based on the 1967 play of the same name by Ron Cowen.[2]

Plot

[edit]In 1970, 20-year-old Jerry (Michael Douglas) visits his parents Herb (Jack Warden) and Ruth (Barbara Bel Geddes) to tell them he is considering dropping out of university to find himself. His parents are worried, not only because they have wasted expensive tuition on Jerry, but also because the Vietnam War is raging and by dropping out, Jerry will lose his student draft deferral.

Inspired by a television advertisement, Jerry becomes a Big Brother to a black child named Marvis (Kirk Calloway). When Marvis is slightly injured in a fall, they visit a hospital where Jerry meets a nurse named Vanetta (Brenda Vaccaro). Jerry and Vanetta soon fall in love, despite Vanetta being older than Jerry, and they begin living together. Jerry accidentally discovers an autographed photo of Vanetta declaring her love to a man named Tony (Bill Vint). Vanetta explains that Tony is her husband and they separated two years ago, although they are not divorced.

Jerry follows through on his plan to drop out of university. Confident in his self-taught guitar playing, he auditions for the conservatorium and gets a regular paying gig playing at a local coffeehouse. Herb discovers that Jerry has dropped out when he receives Jerry's draft notice in the mail. Jerry is initially not worried because he expects to be accepted to the conservatorium, which would restore his student draft deferral. Unfortunately, despite his impressive audition, the conservatorium rejects him for lack of any formal musical training. He investigates other ways to evade the draft, to no avail.

Jerry's streak of bad luck continues when Marvis's older brother is killed in Vietnam and Marvis takes his anger out on Jerry, ending their relationship. Next, Tony, having just returned from Vietnam wearing his Marine uniform, comes to Vanetta's apartment while she is out, and tells Jerry that Vanetta promised to wait for him. When Vanetta comes home, Jerry leaves to let her and Tony deal with their personal issues. Jerry buys an old Ford Falcon and plans to flee to Canada to evade the draft. Vanetta, torn between Tony and Jerry, decides not to accompany Jerry to Canada.

The night before Jerry is supposed to report for his induction physical, he visits his parents to tell them he is going to Canada and to say goodbye. After a family argument, Herb appears to accept his decision, but urges him to have his car inspected for safety at the local gas station the next day, and even buys him a set of new tires. While Jerry looks at some road maps, he overhears Herb attempting to bribe the gas station mechanic to disable Jerry's car so it cannot run for a few days, in order to prevent Jerry's departure. Jerry bursts into tears and drives his car out of the station into another car being towed by a tow truck.

In the final scene, Herb and Ruth go to bed as their bedroom television broadcasts news footage of action in Vietnam. As they close their eyes, the television shows a close-up of a dying Jerry being carried away by fellow soldiers.

Cast

[edit]- Michael Douglas as Jerry McAdams

- Jack Warden as Herb McAdams

- Brenda Vaccaro as Vanetta

- Barbara Bel Geddes as Ruth McAdams

- Kirk Calloway as Marvis

- Bill Vint as Tony

- Jeff Siggins as Bennie

- Rob Reiner as Don

- William Smith as Draft Lawyer

- Garry Goodrow as Ginsberg

- Dennis Fimple as Shelly

Production

[edit]Michael Douglas had been cast in the original play on Broadway but was fired from his role and replaced with David Birney. His father Kirk Douglas bought the rights to the play and filmed it with his son in the lead he lost.[3]

The title refers to a tree house that Jerry returns to sit in.

During the low-budget production, Brenda Vaccaro and Michael Douglas initially shared the same trailer, then began a six-year relationship.[4] She guest starred twice with him in The Streets of San Francisco, playing a rookie cop in season 1, episode 15, and a hit-woman in season 3, episode 2, during that time.

Critical reception

[edit]Roger Greenspun of The New York Times did not care for the film:

Summertree is a bad movie, but its badness proceeds not from its intentions, which seem honorable, or from its stylistic analogies to past modes, which in different hands could have been interesting. The badness exists, rather, moment by moment, in the insufficiency of each acted scene, in the niggling insecurity of Newley's camera, in the improverishment of each evocation of a quality of life—from the boy's dull guitar playing, which is supposed to be great, to the father's love of hunting, which should recreate the landscape, but only signifies a thoughtless and cruel pastime.[5]

The Variety reviewer wrote "Newley brings individual scenes beautifully to life, with Douglas clearly defining his role as the personable-but-self-centered hero. Miss Vaccaro, despite the character's indecisiveness, is charming. The two of them make their love story fresh and believable."[6] Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune gave the film 2 stars out of 4 and called it "occasionally moving," but found the relationships to "lack believability" and the ending "an ironic statement that is decidedly out of place."[7] Richard Combs of The Monthly Film Bulletin wrote that Michael Douglas' performance "has an energy and vitality that gives an edge to the theme of wasted youth. Other elements in Summertree blend less successfully—the contrived spontaneity of Jerry's romance with Vanetta and the fragmentary treatment of his relationship with the negro boy. Anthony Newley's direction, however, is surprisingly unselfconscious and responsive to a talented cast, though there is little he can do with the over-neat tying together of all the ironies in the last half hour."[8]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ The New York Times. June 6, 1971. D31. "'SUMMERTREE' — Michael Douglas stars in the film, arriving Wednesday at neighborhood houses."

- ^ "Ron Cowen - complete guide to the Playwright, Plays, Theatres, Agent". Doollee.com. Retrieved 2010-08-16.

- ^ p.53 Douglas, Kirk Let's Face It: 90 years of Living, Loving, and Learning 2007 John Wiley and Sons

- ^ "Michael Douglas & Brenda Vaccaro: Is Out-of-Wedlock No Longer In?". People.com. 1974-09-02. Retrieved 2010-08-16.

- ^ Greenspun, Roger (1971-06-17). "Newley's 'Summertree' Opens:Hume and Yafa Work Revisits the 40s Death of a Serviceman Fixes the Action". The New York Times.

- ^ "Film Reviews: Summertree". Variety. June 16, 1971. 15.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (July 12, 1971). "Summertree". Chicago Tribune. Section 2, p. 13.

- ^ Combs, Richard (February 1972). "Summertree". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 39 (457): 38.

External links

[edit]- Summertree at IMDb

Summertree

View on GrokipediaOriginal Play

Plot Summary

The play Summertree centers on a young man approaching his twentieth birthday, depicted in a non-linear structure that interweaves his present mortal peril in Vietnam with flashbacks to his domestic life. Chronologically, the protagonist leads an unstructured existence at home, more absorbed in personal pursuits like playing piano than in maintaining college enrollment, which would qualify him for a II-S student deferment from the Selective Service System amid escalating U.S. military needs in Vietnam during 1967.[4][2] His avoidance of academic responsibilities heightens familial strain, as his traveling salesman father presses for vocational pragmatism or the disciplining structure of military service, viewing the son's aimlessness as a failure of maturity.[4][5] Tensions escalate through confrontations revealing generational divides: the father embodies traditional expectations of self-reliance and confronts the son over relinquishing college for artistic dreams, while the possessive yet affectionate mother engages in teasing, protective exchanges that underscore emotional dependency.[2] The young man shares lighthearted, intimate moments with his girlfriend, evoking college-era levity amid broader uncertainties, but these do not resolve his internal conflict over evading or embracing conscription—options including Canada flight or continued deferment were viable for many peers, though he rejects them.[4] Opting instead to enlist voluntarily, he deploys to Vietnam, where battlefield scenes culminate in his fatal wounding.[4] In his final moments, leaning against a jungle tree that mirrors the backyard "summertree" of his youth, the protagonist reflects on these events, confronting a spectral soldier version of himself and recognizing the irreversible cost of his choices, as his father belatedly grasps the hollow triumph of enforced discipline.[4][2] The narrative arc traces this path from suburban indecision to wartime demise, framed by the protagonist's introspective monologues.[5]Characters and Structure

The play centers on the Young Man, the protagonist and archetypal figure of 1960s youth adrift in personal and societal flux, depicted as intellectually capable but chronically indecisive, prioritizing unstructured pursuits like music and leisure over conventional paths such as college completion, which precipitates his draft vulnerability and enlistment. His choices illustrate individual agency yielding unintended consequences, from familial tensions to battlefield mortality.[1] Supporting characters reinforce this through relational dynamics: the Mother, an overprotective figure whose indulgence facilitates the protagonist's evasion of accountability; the Father, embodying disciplined, duty-bound traditionalism as a working-class provider urging practical stability; and the Girl, his girlfriend, representing ephemeral romantic idealism amid his aimless drift.[3] Complementary roles include the Boy, a neighborhood youth functioning as a surrogate sibling or younger self, mirroring the protagonist's unresolved immaturity, and the Soldier, who interjects war's stark immediacy to underscore external pressures on personal trajectories.[2] Dramaturgically, Summertree employs a non-linear framework anchored in the Young Man's dying reflections in Vietnam, blending fragmented flashbacks, introspective monologues, and direct audience addresses to delineate causal linkages between domestic indecision, relational enablement, and irreversible enlistment. This stream-of-consciousness form prioritizes internal psychological causation over chronological exposition, revealing how incremental choices compound into fatality. The sparse ensemble of six roles—three male adults, two female adults, and one boy—fosters concentrated realism, eschewing ensemble spectacle for probing interpersonal and intrapersonal drivers of outcome.[2]Themes and Symbolism

The play examines the conflict between personal autonomy and the demands of responsibility, portraying protagonist Jerry's college dropout and pursuit of music as an assertion of freedom that directly erodes his draft deferment, culminating in enlistment and death rather than deliberate anti-war heroism.[2] [6] This sequence illustrates causal consequences of evading structured obligations, where unstructured idleness amplifies vulnerability to compulsory service, contrasting romanticized self-expression with pragmatic adult duties.[7] Familial dynamics serve as a microcosm for broader societal shortcomings in fostering accountability, with parents enabling Jerry's aimless drift through permissive support, mirroring how draft evasion proliferated amid lenient enforcement—over 210,000 men accused by Selective Service, yet prosecutions remained limited, with only around 6,800 convictions from 1964 to 1972.[8] [9] Such enabling delays confrontation with reality, as Jerry's unresolved identity crisis—fueled by generational indulgence—propels him toward fatal choices, underscoring how avoidance of duty compounds personal and collective risks. The titular "summertree" evokes transient youth, representing a brief phase of vitality and rebellion that ignores inexorable cycles of growth, decay, and renewal, much like seasonal trees that flourish then shed leaves under natural imperatives. This imagery critiques idealized evasion of life's binding structures, where anti-establishment pursuits neglect temporal and biological pressures toward maturity and contribution. While the narrative conveys genuine grief over war's toll, it highlights, through Jerry's arc, the first-principles necessity of balancing individual desires against communal defense mechanisms, without which societies falter against existential threats.[10][2]Production History

Premiere and Broadway Run

Summertree received its first staged readings and development at the Eugene O'Neill National Playwrights Conference in Waterford, Connecticut, during the summer of 1967, where playwright Ron Cowen, then a graduate student in his early twenties, worked with director Lloyd Richards and actors on an initial script of approximately 130 pages.[11] The play opened Off-Broadway on March 3, 1968, at the Repertory Theatre of Lincoln Center in New York City, under the auspices of the Lincoln Center Repertory Company.[12] This production featured a minimalist staging that contributed to its intimate, non-commercial appeal amid the competitive Off-Broadway scene of the late 1960s.[4] The original cast included David Birney in the lead role, earning him a Theatre World Award for his performance, and Blythe Danner in a supporting role.[12] Directed as part of Lincoln Center's repertory efforts to showcase emerging works, the production ran for a limited engagement, reflecting the era's focus on workshop-developed plays rather than extended commercial viability.[13] Cowen's background in academic and conference settings, including this O'Neill workshop, underscored the play's origins in institutional theater development programs rather than traditional Broadway pathways.[11] No transfer to Broadway occurred, distinguishing it from more commercially oriented transfers of the period.[12]Subsequent Stage Productions

Following its premiere and Broadway engagement, Summertree saw sporadic revivals confined largely to university theaters, with no evidence of major professional regional mounts, international tours, or extended commercial runs.[2][14] Wright State University staged the play during the 1974–1975 academic year as part of its theater program.[14] Ohio University Lancaster Campus Theatre presented a production in 1978.[15] These instances highlight occasional academic interest in the script for exploring interpersonal dynamics and anti-war sentiments, typically adhering to the original text without significant adaptations.[2] Licensing rights are held by Dramatists Play Service, Inc., which charges a performance fee of $105 per show—a rate consistent with niche, low-volume usage rather than mainstream viability.[2] The scarcity of documented post-1970s professional revivals further indicates limited enduring stage traction beyond educational contexts.[2]Film Adaptation Development

In March 1968, Bryna Productions, the company founded by Kirk Douglas, acquired the film rights to Ron Cowen's play Summertree, shortly after its Off-Broadway premiere.[16] This acquisition marked the first project under a new production agreement between Bryna Productions and Columbia Pictures.[17] The screenplay was adapted by Edward Hume and Stephen Yafa, who restructured elements of Cowen's original stage work to suit cinematic presentation while retaining its focus on interpersonal and societal tensions.[18][17] Kirk Douglas served as producer, selecting Anthony Newley to direct, with his son Michael Douglas cast in the lead role—a decision influenced by Michael's prior stage portrayal of the character in an early professional production of the play.[17] This marked Michael Douglas's feature film debut. Principal photography took place in 1970, emphasizing contained, dialogue-heavy sequences to preserve the intimacy of the source material's chamber-drama style over expansive action elements.[1] The film was released by Columbia Pictures in June 1971, following the Tet Offensive but amid ongoing U.S. military involvement in Vietnam prior to significant troop drawdowns.[17]Film Version

Casting and Direction

The 1971 film adaptation of Summertree was directed by Anthony Newley, an English actor, singer, and songwriter renowned for his work in musical theater, including co-writing and directing the 1961 stage production Stop the World – I Want to Get Off. Newley's selection as director marked his only solo feature film effort, shifting from stage spectacles to a more contained dramatic narrative focused on personal and familial tensions amid the Vietnam draft. His background in musical performance influenced the inclusion of subtle auditory motifs, though the score was composed by David Shire, with Newley's oversight emphasizing introspective character moments through close-up cinematography rather than expansive action sequences.[3][1] Michael Douglas was cast in the lead role of Jerry McAdams, the college dropout grappling with draft avoidance and life choices, marking Douglas's feature film debut at age 26. Fresh from earning a B.A. in drama at the University of California, Santa Barbara in 1968 and subsequent acting studies in New York, Douglas brought an unpolished authenticity to the youthful protagonist, informed by his recent stage experience in the original Broadway production from which he had been dismissed. The casting exemplified nepotism, as producer Kirk Douglas—Michael's father—purchased the film rights specifically to launch his son's career following the stage firing, yet Douglas's raw delivery aligned with the character's causal chain of regret over deferred responsibilities.[19][20][21] Supporting roles featured Jack Warden as Herb McAdams, the pragmatic father, drawing on Warden's established screen presence as a no-nonsense authority figure honed in over 20 prior films, including his 1957 portrayal of Juror No. 7 in 12 Angry Men. Brenda Vaccaro portrayed Vanetta, Jerry's older romantic interest and nurse, capitalizing on Vaccaro's recent Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actress in Midnight Cowboy (1969), which showcased her ability to convey emotional vulnerability in complex relationships. Kirk Douglas, absent from the acting ensemble, served as producer through his Bryna Productions, enabling the familial dynamic off-screen while his real-life advocacy for military service during World War II informed the project's pro-duty undertones, though he deferred paternal casting to Warden for narrative focus.[22][1][23]