Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Viet Cong

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

The Viet Cong[nb 1] (VC) was an epithet and umbrella term to refer to the communist-driven armed movement and united front organization in South Vietnam. It was formally organized as and led by the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam,[nb 2] and conducted military operations under the name of the Liberation Army of South Vietnam (LASV). The movement fought under the direction of North Vietnam against the South Vietnamese and United States governments during the Vietnam War. The organization had both guerrilla and regular army units, as well as a network of cadres who organized and mobilized peasants in the territory the VC controlled. During the war, communist fighters and some anti-war activists claimed that the VC was an insurgency indigenous to the South that represented the legitimate rights of people in South Vietnam, while the U.S. and South Vietnamese governments portrayed the group as a tool of North Vietnam. It was later conceded by the modern Vietnamese communist leadership that the movement was actually under the North Vietnamese political and military leadership, aiming to unify Vietnam under a single banner.

North Vietnam established the National Liberation Front (NLF) on December 20, 1960, at Tân Lập village in Tây Ninh Province to foment insurgency in the South. Many of the VC's core members were volunteer "regroupees", southern Viet Minh who had resettled in the North after the Geneva Accord (1954). Hanoi gave the regroupees military training and sent them back to the South along the Ho Chi Minh trail in the late 1950s and early 1960s. The VC called for the unification of Vietnam and the overthrow of the American-backed South Vietnamese government. The VC's best-known action was the Tet Offensive, an assault on more than 100 South Vietnamese urban centers in 1968, including an attack on the U.S. embassy in Saigon. The offensive riveted the attention of the world's media for weeks, but also overextended the VC. Later communist offensives were conducted predominantly by the North Vietnamese. The organization officially merged with the Fatherland Front of Vietnam on February 4, 1977, after North and South Vietnam were officially unified under a communist government.

Names

[edit]Việt Cộng is a contraction of Việt Nam cộng sản ('Vietnamese communist').[10] By the late 1940s, Vietnamese anti-communist nationalist groups had begun employing the term Việt Cộng in their publications.[11] Since the early 1950s, the State of Vietnam used the term to depict Vietnamese communists, hiding behind the mask of the Viet Minh front, as false patriots serving the foreign communist powers.[12]: 695–696 The earliest citation for Viet Cong in English is from 1957.[13] American soldiers referred to the Viet Cong as Victor Charlie or VC. "Victor" and "Charlie" are both letters in the NATO phonetic alphabet. "Charlie" referred to communist forces in general, both South Vietnamese 'Liberation Front' and North Vietnamese People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN).

The official Vietnamese history gives the Southern group's name as the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam (NLFSV; Mặt trận Dân tộc Giải phóng miền Nam Việt Nam).[14][nb 3] Many writers shorten this to National Liberation Front (NLF).[nb 4] In 1969, the NLF created the "Provisional Revolutionary Government of the Republic of South Vietnam" (Chính phủ Cách mạng Lâm thời Cộng hòa Miền Nam Việt Nam), abbreviated PRG.[nb 5] Although the NLF was not officially abolished until 1977, the NLF no longer used the name after the PRG was created. Members generally referred to the NLF as "the Front" (Mặt trận).[10] Their armed wing was the "Liberation Army of South Vietnam" (Quân Giải phóng Miền Nam Việt Nam).[15]

History

[edit]Origin

[edit]

By the terms of the Geneva Accord (1954), which ended the Indochina War, France and the Viet Minh agreed to a truce and to a separation of forces. The Viet Minh had become the government of North Vietnam, and military forces of the communists regrouped there. Military forces of the non-communists regrouped in South Vietnam, which became a separate state. Elections on reunification were scheduled for July 1956. A divided Vietnam angered Vietnamese nationalists, but it made the country less of a threat to China. Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai negotiated the terms of the ceasefire with France and then imposed them on the Viet Minh.

About 90,000 Viet Minh were evacuated to the North while 5,000 to 10,000 cadre remained in the South, most of them with orders to refocus on political activity and agitation.[10] The Saigon-Cholon Peace Committee, the first VC front, was founded in 1954 to provide leadership for this group.[10] Other front names used by the VC in the 1950s implied that members were fighting for religious causes, for example, "Executive Committee of the Fatherland Front", which suggested affiliation with the Hòa Hảo sect, or "Vietnam-Cambodia Buddhist Association".[10] Front groups were favored by the VC to such an extent that its real leadership remained shadowy until long after the war was over, prompting the expression "the faceless Viet Cong".[10]

Led by Ngô Đình Diệm, South Vietnam refused to sign the Geneva Accord. Arguing that a free election was impossible under the conditions that existed in communist-held territory, Diệm announced in July 1955 that the scheduled election on reunification would not be held. After subduing the Bình Xuyên organized crime gang in the Battle for Saigon in 1955, and the Hòa Hảo and other militant religious sects in early 1956, Diệm turned his attention to the VC.[16] Within a few months, the Viet Cong had been driven into remote swamps.[17] The success of this campaign inspired U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower to dub Diệm the "miracle man" when he visited the U.S. in May 1957.[17] France withdrew its last soldiers from Vietnam in April 1956.[18]

In March 1956, southern communist leader Lê Duẩn presented a plan to revive the insurgency entitled "The Road to the South" to the other members of the Politburo in Hanoi.[19]: 16 He argued adamantly that war with the United States was necessary to achieve unification.[19]: 21 But as China and the Soviets both opposed confrontation at this time, Lê Duẩn's plan was rejected and communists in the South were ordered to limit themselves to economic struggle.[19]: 16 Leadership divided into a "North first", or pro-Beijing, faction led by Trường Chinh, and a "South first" faction led by Lê Duẩn.

As the Sino-Soviet split widened in the following months, Hanoi began to play the two communist giants off against each other. The North Vietnamese leadership approved tentative measures to revive the southern insurgency in December 1956.[20] Lê Duẩn's blueprint for revolution in the South was approved in principle, but implementation was conditional on winning international support and on modernizing the army, which was expected to take at least until 1959.[19]: 19 President Ho Chi Minh stressed that violence was still a last resort.[21] Nguyễn Hữu Xuyên was assigned military command in the South,[19]: 20 replacing Lê Duẩn, who was appointed North Vietnam's acting party boss. This represented a loss of power for Hồ, who preferred the more moderate Võ Nguyên Giáp, who was defense minister.[19]: 21

An assassination campaign, referred to as "extermination of traitors" [23] or "armed propaganda" in communist literature, began in April 1957. Tales of sensational murder and mayhem soon crowded the headlines.[10] Seventeen civilians were killed by machine gun fire at a bar in Châu Đốc in July and in September a district chief was killed with his entire family on a main highway in broad daylight.[10] In October 1957, a series of bombs exploded in Saigon and left 13 Americans wounded.[10]

In a speech given on September 2, 1957, Hồ reiterated the "North first" line of economic struggle.[19]: 23 The launch of Sputnik in October boosted Soviet confidence and led to a reassessment of policy regarding Indochina, long treated as a Chinese sphere of influence. In November, Hồ traveled to Moscow with Lê Duẩn and gained approval for a more militant line.[19]: 24–5 In early 1958, Lê Duẩn met with the leaders of "Inter-zone V" (northern South Vietnam) and ordered the establishment of patrols and safe areas to provide logistical support for activity in the Mekong Delta and in urban areas.[19]: 24 In June 1958, the VC created a command structure for the eastern Mekong Delta.[24] French scholar Bernard Fall published an influential article in July 1958 which analyzed the pattern of rising violence and concluded that a new war had begun.[10]

Launches armed struggle

[edit]The Communist Party of Vietnam approved a "people's war" on the South at a session in January 1959 and this decision was confirmed by the Politburo in March.[18] In May 1959, Group 559 was established to maintain and upgrade the Ho Chi Minh trail, at this time a six-month mountain trek through Laos. About 500 of the "regroupees" of 1954 were sent south on the trail during its first year of operation.[25] The first arms delivery via the trail, a few dozen rifles, was completed in August 1959.[26]

Two regional command centers were merged to create the Central Office for South Vietnam (Trung ương Cục miền Nam), a unified communist party headquarters for the South.[18] COSVN was initially located in Tây Ninh Province near the Cambodian border. On July 8, the VC killed two U.S. military advisors at Biên Hòa, the first American dead of the Vietnam War.[nb 6] The "2d Liberation Battalion" ambushed two companies of South Vietnamese soldiers in September 1959, the first large unit military action of the war.[10] This was considered the beginning of the "armed struggle" in communist accounts.[10] A series of uprisings beginning in the Mekong Delta province of Bến Tre in January 1960 created "liberated zones", models of VC-style government. Propagandists celebrated their creation of battalions of "long-hair troops" (women).[27] The fiery declarations of 1959 were followed by a lull while Hanoi focused on events in Laos (1960–61).[19]: 7 Moscow favored reducing international tensions in 1960, as it was election year for the U.S. presidency.[nb 7] Despite this, 1960 was a year of unrest in South Vietnam, with pro-democracy demonstrations inspired by the South Korean student uprising that year and a failed military coup in November.[10]

To counter the accusation that North Vietnam was violating the Geneva Accord, the independence of the VC was stressed in communist propaganda. The VC created the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam in December 1960 at Tân Lập village in Tây Ninh as a "united front", or political branch intended to encourage the participation of non-communists.[19]: 58 The group's formation was announced by Radio Hanoi and its ten-point manifesto called for, "overthrow the disguised colonial regime of the imperialists and the dictatorial administration, and to form a national and democratic coalition administration."[10] Thọ, a lawyer and the VC's "neutralist" chairman, was an isolated figure among cadres and soldiers. South Vietnam's Law 10/59, approved in May 1959, authorized the death penalty for crimes "against the security of the state" and featured prominently in VC propaganda.[28] Violence between the VC and government forces soon increased drastically from 180 clashes in January 1960 to 545 clashes in September.[29][30]

By 1960, the Sino-Soviet split was a public rivalry, making China more supportive of Hanoi's war effort.[31] For Chinese leader Mao Zedong, aid to North Vietnam was a way to enhance his "anti-imperialist" credentials for both domestic and international audiences.[32] About 40,000 communist soldiers infiltrated the South in 1961–63.[19]: 76 The VC grew rapidly; an estimated 300,000 members were enrolled in "liberation associations" (affiliated groups) by early 1962.[10] The ratio of VC to government soldiers jumped from 1:10 in 1961 to 1:5 a year later.[33]

The level of violence in the South jumped dramatically in the fall of 1961, from 50 guerrilla attacks in September to 150 in October.[19]: 113 U.S. President John F. Kennedy decided in November 1961 to substantially increase American military aid to South Vietnam.[34] The USS Core arrived in Saigon with 35 helicopters in December 1961. By mid-1962, there were 12,000 U.S. military advisors in Vietnam.[35] The "special war" and "strategic hamlets" policies allowed Saigon to push back in 1962, but in 1963 the VC regained the military initiative.[33] The VC won its first military victory against South Vietnamese forces at Ấp Bắc in January 1963.

A landmark party meeting was held in December 1963, shortly after a military coup in Saigon in which Diệm was assassinated. North Vietnamese leaders debated the issue of "quick victory" vs "protracted war" (guerrilla warfare).[19]: 74–5 After this meeting, the communist side geared up for a maximum military effort and the troop strength of the PAVN increased from 174,000 at the end of 1963 to 300,000 in 1964.[19]: 74–5 The Soviets cut aid in 1964 as an expression of annoyance with Hanoi's ties to China.[36][nb 8] Even as Hanoi embraced China's international line, it continued to follow the Soviet model of reliance on technical specialists and bureaucratic management, as opposed to mass mobilization.[36] The winter of 1964–1965 was a high-water mark for the VC, with the Saigon government on the verge of collapse.[37] Soviet aid soared following a visit to Hanoi by Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin in February 1965.[38] Hanoi was soon receiving up-to-date surface-to-air missiles.[38] The U.S. would have 200,000 soldiers in South Vietnam by the end of the year.[39]

In January 1966, Australian troops uncovered a tunnel complex that had been used by COSVN.[40] Six thousand documents were captured, revealing the inner workings of the VC. COSVN retreated to Mimot in Cambodia. As a result of an agreement with the Cambodian government made in 1966, weapons for the Viet Cong were shipped to the Cambodian port of Sihanoukville and then trucked to VC bases near the border along the "Sihanouk Trail", which replaced the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

Many VC units operated at night,[41] and employed terror as a standard tactic.[42] Rice procured at gunpoint sustained the Viet Cong.[43] Squads were assigned monthly assassination quotas.[44] Government employees, especially village and district heads, were the most common targets. But there were a wide variety of targets, including clinics and medical personnel.[44] Notable VC atrocities include the massacre of over 3,000 unarmed civilians at Huế, 48 killed in the bombing of My Canh floating restaurant in Saigon in June 1965[45] and a massacre of 252 Montagnards in the village of Đắk Sơn in December 1967 using flamethrowers.[46] VC death squads assassinated at least 37,000 civilians in South Vietnam; the real figure was far higher since the data mostly cover 1967–72. They also waged a mass murder campaign against civilian hamlets and refugee camps; in the peak war years, nearly a third of all civilian deaths were the result of VC atrocities.[47] Ami Pedahzur has written that "the overall volume and lethality of Vietcong terrorism rivals or exceeds all but a handful of terrorist campaigns waged over the last third of the twentieth century".[48]

Logistics and equipment

[edit]

Tet Offensive

[edit]Major reversals in 1966 and 1967, as well as the growing American presence in Vietnam, inspired Hanoi to consult its allies and reassess strategy in April 1967. While Beijing urged a fight to the finish, Moscow suggested a negotiated settlement.[19]: 115 Convinced that 1968 could be the last chance for decisive victory, General Nguyễn Chí Thanh, suggested an all-out offensive against urban centers.[19]: 116–7 [nb 9] He submitted a plan to Hanoi in May 1967.[19]: 116–7 After Thanh's death in July, Giáp was assigned to implement this plan, now known as the Tet Offensive. The Parrot's Beak, an area in Cambodia only 30 miles (48 km) from Saigon, was prepared as a base of operations.[49] Funeral processions were used to smuggle weapons into Saigon.[49] VC entered the cities concealed among civilians returning home for Tết.[49] The U.S. and South Vietnamese expected that an announced seven-day truce would be observed during Vietnam's main holiday.

At this point, there were about 500,000 U.S. troops in Vietnam,[39] as well as 900,000 allied forces.[49] General William Westmoreland, the U.S. commander, received reports of heavy troop movements and understood that an offensive was being planned, but his attention was focused on Khe Sanh, a remote U.S. base near the DMZ.[50] In January and February 1968, some 80,000 VC struck more than 100 towns with orders to "crack the sky" and "shake the Earth."[51] The offensive included a commando raid on the U.S. Embassy in Saigon and the massacre at Huế of about 3,500 residents.[52] House-to-house fighting between VC and South Vietnamese Rangers left much of Cholon, a section of Saigon, in ruins. The VC used any available tactic to demoralize and intimidate the population, including the assassination of South Vietnamese commanders.[53] A photo by Eddie Adams showing the summary execution of a VC in Saigon on February 1 became a symbol of the brutality of the war.[54] In an influential broadcast on February 27, newsman Walter Cronkite stated that the war was a "stalemate" and could be ended only by negotiation.[55]

The offensive was undertaken in the hope of triggering a general uprising, but urban Vietnamese did not respond as the VC anticipated. About 75,000 VC/PAVN soldiers were killed or wounded, according to Trần Văn Trà, commander of the "B-2" district, which consisted of southern South Vietnam.[56] "We did not base ourselves on scientific calculation or a careful weighing of all factors, but...on an illusion based on our subjective desires", Trà concluded.[57] Earle G. Wheeler, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, estimated that Tet resulted in 40,000 communist dead[58] (compared to about 10,600 U.S. and South Vietnamese dead). "It is a major irony of the Vietnam War that our propaganda transformed this debacle into a brilliant victory. The truth was that Tet cost us half our forces. Our losses were so immense that we were unable to replace them with new recruits", said PRG Justice Minister Trương Như Tảng.[58] Tet had a profound psychological impact because South Vietnamese cities were otherwise safe areas during the war.[59] U.S. President Lyndon Johnson and Westmoreland argued that panicky news coverage gave the public the unfair perception that America had been defeated.[60]

Aside from some districts in the Mekong Delta, the VC failed to create a governing apparatus in South Vietnam following Tet, according to an assessment of captured documents by the U.S. CIA.[61] The breakup of larger VC units increased the effectiveness of the CIA's Phoenix Program (1968–72), which targeted individual leaders, as well as the Chiêu Hồi Program, which encouraged defections. By the end of 1969, there was little communist-held territory, or "liberated zones", in the rural lowlands of Cochin China, according to the official communist military history.[62] The US military believed that 70 percent of communist main-force combat troops in the South were northerners,[63] but most communist military personnel were not main-force combat troops. Even in early 1970, MACV estimated that northerners made up no more than 45 percent of communist military forces overall in South Vietnam.[64]

The VC created an urban front in 1968 called the Alliance of National, Democratic, and Peace Forces (ANDPF). in other to mobilize and attract support from non-communist opposition groups in the then-South Vietnamese politics.[65] The group's manifesto called for an independent, neutralist, non-aligned South Vietnam and stated that "national reunification cannot be achieved overnight."[65] In June 1969, the alliance merged with the VC to form a "Provisional Revolutionary Government" (PRG). Both the NLF and ANDPF were subsequently merged into the contemporary Vietnam Fatherland Front after 1975.

Vietnamization

[edit]The Tet Offensive increased American public discontent with participation in the Vietnam War and led the U.S. to gradually withdraw combat forces and to shift responsibility to the South Vietnamese, a process called Vietnamization. Pushed into Cambodia, the VC could no longer draw South Vietnamese recruits.[63] In May 1968, Trường Chinh urged "protracted war" in a speech that was published prominently in the official media, so the fortunes of his "North first" faction may have revived at this time.[19]: 138 COSVN rejected this view as "lacking resolution and absolute determination."[19]: 139 The Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968 led to intense Sino-Soviet tension and to the withdrawal of Chinese forces from North Vietnam. Beginning in February 1970, Lê Duẩn's prominence in the official media increased, suggesting that he was again top leader and had regained the upper hand in his longstanding rivalry with Trường Chinh.[19]: 53 After the overthrow of Prince Sihanouk in March 1970, the VC faced a hostile Cambodian government which authorized a U.S. offensive against its bases in April. However, the capture of the Plain of Jars and other territory in Laos, as well as five provinces in northeastern Cambodia, allowed the North Vietnamese to reopen the Ho Chi Minh trail.[19]: 52 Although 1970 was a much better year for the VC than 1969,[19]: 52 it would never again be more than an adjunct to the PAVN. The 1972 Easter Offensive was a direct North Vietnamese attack across the DMZ.[66] Despite the Paris Peace Accords, signed by all parties in January 1973, fighting continued. In March, Trà was recalled to Hanoi for a series of meetings to hammer out a plan for an enormous offensive against Saigon.[67]

Fall of Saigon

[edit]In response to the anti-war movement, the U.S. Congress passed the Case–Church Amendment to prohibit further U.S. military intervention in Vietnam in June 1973 and reduced aid to South Vietnam in August 1974.[69] With U.S. bombing ended, communist logistical preparations could be accelerated. An oil pipeline was built from North Vietnam to VC headquarters in Lộc Ninh, about 75 miles (121 km) northwest of Saigon. (COSVN was moved back to South Vietnam following the Easter Offensive.) The Ho Chi Minh Trail, beginning as a series of treacherous mountain tracks at the start of the war, was upgraded throughout the war, first into a road network driveable by trucks in the dry season, and finally, into paved, all-weather roads that could be used year-round, even during the monsoon.[70] Between the beginning of 1974 and April 1975, with now-excellent roads and no fear of air interdiction, the North delivered nearly 365,000 tons of war matériel to battlefields, 2.6 times the total for the previous 13 years.[71]

The success of the 1973–74 dry season offensive convinced Hanoi to accelerate its timetable. When there was no U.S. response to a successful PAVN attack on Phước Bình in January 1975, South Vietnamese morale collapsed. The next major battle, at Buôn Ma Thuột in March, was a walkover. After the fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975, the PRG moved into government offices there. At the victory parade, Tạng noticed that the units formerly dominated by southerners were missing, replaced by northerners years earlier.[63] The bureaucracy of the Republic of Vietnam was uprooted and authority over the South was assigned to the PAVN. People considered tainted by association with the former South Vietnamese government were sent to re-education camps, despite the protests of the non-communist PRG members including Tạng.[72] Without consulting the PRG, North Vietnamese leaders decided to rapidly dissolve the PRG at a party meeting in August 1975.[73] North and South were merged as the Socialist Republic of Vietnam in July 1976 and the PRG was dissolved. The VC was merged with the Vietnamese Fatherland Front on February 4, 1977.[72]

Relationship with North Vietnam

[edit]Activists opposing American involvement in Vietnam said that the VC was a nationalist insurgency indigenous to the South.[74] They said that the VC was composed of several parties—the People's Revolutionary Party, the Democratic Party and the Radical Socialist Party[4]—and that VC chairman Nguyễn Hữu Thọ was not a communist.[75]

Anti-communists countered that the VC was merely a front for Hanoi.[74] They said some statements issued by communist leaders in the 1980s and 1990s suggested that southern communist forces were influenced by Hanoi.[74] According to the memoirs of Trà, the VC's top commander and PRG defense minister, he followed orders issued by the "Military Commission of the Party Central Committee" in Hanoi, which in turn implemented resolutions of the Politburo.[nb 10] Trà himself was deputy chief of staff for the PAVN before being assigned to the South.[76] The official Vietnamese history of the war states that "The Liberation Army of South Vietnam [Viet Cong] is a part of the People's Army of Vietnam".[14]

See also

[edit]- Viet Cong and PAVN strategy, organization and structure

- Viet Cong and PAVN battle tactics

- Kit Carson Scouts, former Viet Cong who worked with U.S. Marines

- People's Army of Vietnam, the North Vietnamese army

- Viet Cong and People's Army of Vietnam use of terror in the Vietnam War

Notes

[edit]- ^ Vietnamese: Việt Cộng, pronounced [vîət kə̂wŋmˀ] ⓘ; contraction of Việt Nam cộng sản (Vietnamese communist / Viet-communist)[10]

- ^ Sometimes simply National Liberation Front (NLF)

Vietnamese: Mặt trận Dân tộc Giải phóng miền Nam Việt Nam (MTDTGPMNVN)

French: Front national de libération [du Sud Viêt Nam] (FNL) - ^ Radio Hanoi called it the "National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam" in a January 1961 broadcast announcing the group's formation. In his memoirs, Võ Nguyên Giáp called the group the "South Vietnam National Liberation Front" (Nguyên Giáp Võ, Russell Stetler (1970). The Military Art of People's War: Selected Writings of General Vo Nguyen Giap. Monthly Review Press. pp. 206, 208, 210. ISBN 978-0-85345-129-7.). See also the "Program of the National Liberation Front of South Viet-Nam". Archived from the original on June 26, 2010. (1967).

- ^ The terminology "liberation front" is adapted from the earlier Greek and Algerian National Liberation Fronts.

- ^ This also follows terminology used earlier by leftists in Algeria (Provisional Government of the Algerian Republic).

- ^ Major Dale R. Buis and Master Sergeant Charles Ovnand, the first names to appear on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.

- ^ This is sometimes referred to as the "Genoa Policy" and later inspired Khrushchev to take credit for Kennedy's election.(Lynn-Jones, Sean M.; Steven E. Miller; Stephen Van Evera (1989). Soviet Military Policy: An International Security Reader. MIT Press. p. 28. ISBN 0-262-62066-9.)

- ^ There was also a U.S. presidential election in 1964.

- ^ Disappointed with the results of the 1964 U.S. presidential election, the Kremlin did not try to influence the election of 1968. Desiring "businesslike" relations, the Kremlin favored incumbent Richard Nixon against left-wing challenger George McGovern in 1972. (Lynn-Jones, p. 29).

- ^ Trà begins, "How did the B2 theater carry out the mission assigned it by the Military Commission of the Party Central Committee?" (Trần Văn Trà (1982), Vietnam: History of the Bulwark B2 Theatre, archived from the original on June 2, 2011)

References

[edit]- ^ "National Liberation Front (Viet Cong)". www.fotw.info. Archived from the original on April 18, 2023.

- ^ Berg, Nicole M. (July 29, 2020). Discovering Kubrick's Symbolism: The Secrets of the Films. McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-3992-5 – via Google Books.

- ^ Gibson, Karen Bush (February 4, 2020). The Vietnam War. Mitchell Lane. ISBN 978-1-5457-4946-3 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c Burchett, Wilfred (1963): "Liberation Front: Formation of the NLF", The Furtive War, International Publishers, New York. (Archive)

- ^ Possibly a pseudonym for Trần Văn Trà. "Man in the News: Lt.-Gen. Tran Van Tra". February 2, 1973. Archived from the original on August 23, 2009.

- ^ Bolt, Dr. Ernest. "Provisional Revolutionary Government of South Vietnam (1969–1975)". University of Richmond. Archived from the original on October 26, 2014. Retrieved June 28, 2008.

- ^ "Báo Giải Phóng 60 tuổi". Retrieved April 27, 2025.

- ^ "Báo Giải Phóng kiên cường trên tuyến lửa". Báo Đại Đoàn Kết. January 8, 2024. Retrieved April 27, 2025.

- ^ Logevall, Fredrik (1993). "The Swedish-American Conflict over Vietnam". Diplomatic History. 17 (3): 421–445. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7709.1993.tb00589.x. JSTOR 24912244.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Origins of the Insurgency in South Vietnam, 1954–1960". The Pentagon Papers. 1971. pp. 242–314. Archived from the original on October 19, 2017. Retrieved June 13, 2008.

- ^ Reilly, Brett (January 31, 2018). "The True Origin of the Term 'Viet Cong'". The Diplomat.

- ^ Tran, Nu-Anh (2023). "Denouncing the 'Việt Cộng': Tales of revolution and betrayal in the Republic of Vietnam". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 53 (4): 686–708. doi:10.1017/S0022463422000790.

- ^ "Viet Cong", Oxford English Dictionary

- ^ a b Military History Institute of Vietnam,(2002) Victory in Vietnam: The Official History of the People's Army of Vietnam, 1954–1975, translated by Merle L. Pribbenow. University Press of Kansas. p. 68. ISBN 0-7006-1175-4.

- ^ See, for example, this story in Viet Nam News, the official English-language newspaper.

- ^ Karnow, p. 238.

- ^ a b Karnow, p. 245.

- ^ a b c "The History Place — Vietnam War 1945–1960". Archived from the original on March 12, 2023. Retrieved June 11, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Ang, Cheng Guan (2002). The Vietnam War from the Other Side. RoutledgeCurzon. p. 16. ISBN 0-7007-1615-7.

- ^ Olson, James; Randy Roberts (1991). Where the Domino Fell: America and Vietnam, 1945–1990. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 67. This decision was made at the 11th Plenary Session of the Lao Động Central Committee.

- ^ Võ Nguyên Giáp. "The Political and Military Line of Our Party". The Military Art of People's War: Selected Writings of General Vo Nguyen Giap. pp. 179–80.

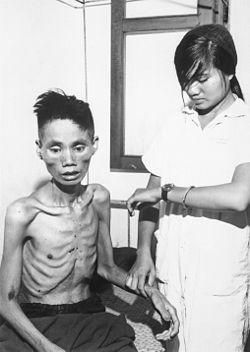

- ^ "The effects of just one month spent in a Viet Cong prison camp show on 23-year-old Le Van Than, who had defected from the Communist forces and joined the Government side, was recaptured by the Viet Cong and deliberately starved". US National Archives Catalog. 1966. Archived from the original on May 4, 2023. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ McNamera, Robert S.; Blight, James G.; Brigham, Robert K. (1999). Argument Without End. PublicAffairs. p. 35. ISBN 1-891620-22-3.

- ^ Karnow, p. 693.

- ^ Victory in Vietnam, p. xi.

- ^ Prados, John, (2006) "The Road South: The Ho Chi Minh Trail", Rolling Thunder in a Gentle Land, editor By Andrew A. Wiest, Osprey Publishing, ISBN 1-84603-020-X.

- ^ Gettleman, Marvin E.; Jane Franklin; Marilyn Young (1995). Vietnam and America. Grove Press. p. 187. ISBN 0-8021-3362-2.

- ^ Gettleman, p. 156.

- ^ Kelly, Francis John (1989) [1973]. History of Special Forces in Vietnam, 1961–1971. United States Army Center of Military History. p. 4. CMH Pub 90-23. Archived from the original on February 12, 2014. Retrieved August 5, 2010.

- ^ Nghia M. Vo Saigon: A History 2011 – Page 140 "... on December 19 to 20, 1960, Nguyễn Hữu Thọ, a Saigon lawyer, Trương Như Tảng, chief comptroller of a bank, Drs. Dương Quỳnh Hoa and Phùng Văn Cung, along with other dissidents, met with communists to form the National Liberation Front..."

- ^ Zhai, Qiang (2000). China and the Vietnam Wars, 1950–1975. Univ of North Carolina Press. p. 83. ISBN 0-8078-4842-5.

- ^ Zhai, p. 5.

- ^ a b Victory in Vietnam, p. xii.

- ^ Pribbenow, Merle (August 1999). "North Vietnam's Master Plan". Vietnam. Archived from the original on April 9, 2023.

- ^ Karnow, p.694

- ^ a b Zhai, p. 128.

- ^ Victory in Vietnam, p. xiii.

- ^ a b Karnow, p. 427.

- ^ a b "1957–1975: The Vietnam War". libcom. Archived from the original on May 17, 2022.

- ^ "VC Tunnels". Digger History.

- ^ Zumbro, Ralph (1986). Tank Sergeant. Presidio Press. pp. 27–28, 115. ISBN 978-0-517-07201-1. The VC were commonly referred to by the Vietnamese rural population as "night bandits" or the "night government".

- ^ Zumbro, pp. 25, 33

- ^ Zumbro, p. 32.

- ^ a b U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee, The Human Cost of Communism in Vietnam (1972), p. 8-49.

- ^ "The My Canh Restaurant bombing". Archived from the original on November 25, 2010. Retrieved July 30, 2008.

- ^ Krohn, Charles, A., The Last Battalion: Controversies and Casualties of the Battle of Hue. pg. 30. Westport 1993.

Jones, C. Don, Massacre at Dak Son Archived November 29, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, United States Information Service, 1967

"On the Other Side: Terror as Policy". Time. December 5, 1969. Archived from the original on May 22, 2013. Retrieved July 17, 2008.

"The Massacre of Dak Son". Time. December 15, 1967. Archived from the original on July 21, 2013. Retrieved June 15, 2008. Pictures of Dak Son can be viewed here. - ^ Guenter Lewy, America in Vietnam, (Oxford University Press, 1978), pp272-3, 448–9.

- ^ Pedahzur, Ami (2006), Root Causes of Suicide Terrorism: The Globalization of Martyrdom, Taylor & Francis, p.116.

- ^ a b c d Westmoreland, William. "The Year of Decision—1968".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) Gettleman, Marvin E (1995). Marvin E. Gettleman; Jane Franklin; Marilyn Young (eds.). Vietnam and America. Grove Press. p. 345. ISBN 0-8021-3362-2. - ^ Westmoreland, p. 344 (editor's note).

- ^ Dougan, Clark; Stephen Weiss (1983). Nineteen Sixty-Eight. Boston: Boston Publishing Company. pp. 8, 10. ISBN 978-0-939526-06-2.

- ^ "The Massacre of Hue". Time. October 31, 1969. Archived from the original on December 4, 2007.

Pike, Douglas. "Viet Cong Strategy of Terror". pp. 23–39. Archived from the original on December 6, 2022. - ^ Kearny, Cresson H. (Maj) (1997). "Jungle Snafus...and Remedies". Oregon Institute of Science and Medicine: 327.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Lee, Nathan (April 10, 2009). "A Dark Glimpse From Eddie Adams's Camera". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 15, 2018.

- ^ Walter Cronkite on the Tet Offensive, archived from the original on July 19, 2008

- ^ Tran Van Tra. "Tet".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) in Warner, Jayne S. Warner (1993). Luu Doan Huynh (ed.). The Vietnam War: Vietnamese and American Perspectives. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe. pp. 49–50.. - ^ Tran Van Tra. "Comments on Tet '68". Archived from the original on August 7, 2011.

- ^ a b "Vietnam Veterans for Academic Reform". Archived from the original on February 26, 2009.

- ^ Crowell, Todd Crowell (October 29, 2006). "The Tet Offensive and Iraq". Archived from the original on August 23, 2009.

- ^ Aron, Paul (November 7, 2005). Mysteries in History. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 404. ISBN 1-85109-899-2.

- ^ "Failure of the Viet Cong to establish liberation committees". Declassified CIA Documents on the Vietnam War. February 22, 1991. Archived from the original on March 7, 2021.

- ^ "Victory in Vietnam: The Official History of the People's Army of Vietnam, 1954–1975." University Press of Kansas, May 2002 (original 1995). Translation by Merle L. Pribbenow. Page 246.

- ^ a b c Porter, Gareth (1993). Vietnam: The Politics of Bureaucratic Socialism. Cornell University Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-8014-2168-6.

- ^ "Order of Battle Summary, 1 - 28 February 1970" (PDF). Combined Intelligence Center Vietnam. Retrieved May 30, 2024. (Virtual Vietnam Archive, Texas Tech University, item #F015900080736), page I-1. MACV estimates of enemy strength were not very reliable, but their political bias if any should have been to exaggerate the proportion of northerners.

- ^ a b Porter, pp. 27–29

- ^ "The Vietcong". www.vietnampix.com. Archived from the original on October 5, 2022.

- ^ Karnow, p. 673.

- ^ Tran Van Tra. "Vietnam: History of the Bulwark B2 Theatre". Archived from the original on May 28, 2009.

- ^ Karnow, pp 644–645.

- ^ Karnow. pp. 672–74.

- ^ Whitcomb, Col Darrel (Summer 2003). "Victory in Vietnam: The Official History of the People's Army of Vietnam, 1954–1975 (book review)". Air & Space Power Journal. Archived from the original on February 7, 2009.

- ^ a b Porter, p. 29

- ^ Porter, p. 28.

- ^ a b c Ruane, Kevin (1998), War and Revolution in Vietnam, 1930–75, Taylor & Francis, p. 51, ISBN 1-85728-323-6

- ^ Karnow, Stanley (1991). Vietnam: A history. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-670-84218-4., p. 255.

- ^ Bolt, Dr. Ernest. "Who is Tran Van Tra?". Archived from the original on July 10, 2011. Retrieved April 7, 2009.

Further reading

[edit]- U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee, The Human Cost of Communism in Vietnam (1972) .

- Marvin Gettleman, et al. Vietnam and America: A Documented History. Grove Press. 1995. ISBN 0-8021-3362-2. See especially Part VII: The Decisive Year.

- Truong Nhu Tang. A Vietcong Memoir. Random House. ISBN 0-394-74309-1. 1985. See Chapter 7 on the forming of the Viet Cong, and Chapter 21 on the communist take-over in 1975.

- Frances Fitzgerald. Fire in the Lake: The Vietnamese and the Americans in Vietnam. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1972. ISBN 0-316-28423-8. See Chapter 4. "The National Liberation Front".

- Douglas Valentine. The Phoenix Program. New York: William Morrow and Company. 1990. ISBN 0-688-09130-X.

- Merle Pribbenow (translation). Victory in Vietnam: The Official History of the People's Army of Vietnam. University Press of Kansas. 2002 ISBN 0-7006-1175-4

- Morris, Virginia and Hills, Clive. 2018. Ho Chi Minh's Blueprint for Revolution: In the Words of Vietnamese Strategists and Operatives, McFarland & Co Inc.

External links

[edit]- Tet Offensive 1968, US Embassy & Saigon fighting. CBS News footage of the Tet Offensive.

- Vietnam War – Hue Massacre 1968. A tribute to the dead of Huế by Trịnh Công Sơn, one of wartime Vietnam's most prominent composers.

- The Wars for Vietnam: 1945–1975. Primary documents concerning the Vietnam War, including peace proposals, treaties, and platforms.

- Digger History, VC Tunnels. At one point, Viet Cong tunnels stretched from the Cambodia border to Saigon.

- The Viet Cong 1965–1967 – part 1 and The Viet Cong 1965–1967 – part 2. What was it like to be a Viet Cong? This recruiting video shows one perspective.

- "Tiên vê Sài Gòn" (Forward to Saigon.) This propaganda video features singing Viet Cong and newsreel footage from the 1975 offensive.