Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Heading (navigation)

View on Wikipedia

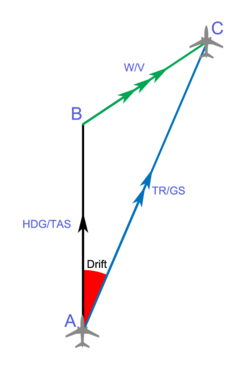

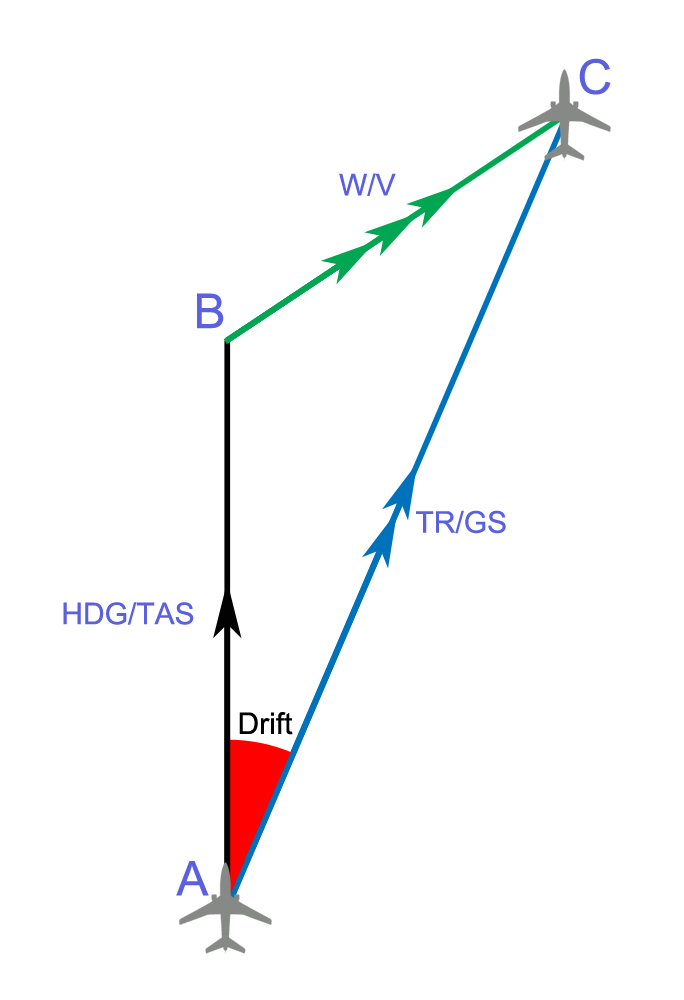

In navigation, the heading of a vessel or aircraft is the compass direction in which the craft's bow or nose is pointed. Note that the heading may not necessarily be the direction that the vehicle actually travels, which is known as its course.[a] Any difference between the heading and course is due to the motion of the underlying medium, the air or water, or other effects like skidding or slipping. The difference is known as the drift, and can be determined by the wind triangle. At least seven ways to measure the heading of a vehicle have been described.[1] Heading is typically based on cardinal directions, so 0° (or 360°) indicates a direction toward true north, 90° true east, 180° true south, and 270° true west.[1]

TVMDC

[edit]

1 - True North

2 - Heading, the direction the vessel is "pointing towards"

3 - Magnetic north, which differs from true north by the magnetic variation.

4 - Compass north, including a two-part error; the magnetic variation (6) and the ship's own magnetic field (5)

5 - Magnetic deviation, caused by vessel's magnetic field.

6 - Magnetic variation, caused by variations in Earth's magnetic field.

7 - Compass heading or compass course, before correction for magnetic deviation or magnetic variation.

8 - Magnetic heading, the compass heading corrected for magnetic deviation but not magnetic variation; thus, the heading reliative to magnetic north.

9, 10 - Effects of crosswind and tidal current, causing the vessel's track to differ from its heading.

A, B - Vessel's track.

TVMDC,AW is a mnemonic for converting from true heading, to magnetic and compass headings. TVMDC is a mnemonic initialism for true heading, variation, magnetic heading, deviation, compass heading, add westerly. The most common use of the TVMDC method is deriving compass courses during nautical navigation from maps. The inverse correction from compass heading to true heading is "CDMVTAE", with compass heading, deviation, magnetic heading, variation, true heading, add easterly The most common use of the CDMVTAE rule is to convert compass headings to map headings.

Background

[edit]The Geographic North Pole around which the Earth rotates is not in exactly the same position as the Magnetic North Pole. From any position on the globe, a direction can be determined to either the Geographic North Pole or to the Magnetic North Pole. These directions are expressed in degrees from 0–360°, and also fractions of a degree. The differences between these two directions at any point on the globe is magnetic variation (also known as magnetic declination, but for the purposes of the mnemonic, the term 'variation' is preferred). When a compass is installed in a vehicle or vessel, local anomalies of the vessel can introduce error into the direction that the compass points. The difference between the local Magnetic North and the direction that the compass indicates as north is known as magnetic deviation.

Determine variation in North America

[edit]Magnetic variation (also known as magnetic declination) is different depending on the geographic position on the globe. The Magnetic North Pole is currently in Northern Canada and is moving generally south. A straight line can be drawn from the Geographic North Pole, down to the Magnetic North Pole and then continued straight down to the equator. This line is known as the agonic line, and the line is also moving. In the year 1900, the agonic line passed roughly through Detroit and then was east of Florida. It currently passes roughly west of Chicago, IL, and through New Orleans, LA. If a navigator is located on the agonic line, then variation is zero: the Magnetic North Pole and the Geographic North Pole appear to be directly in line with each other. If a navigator is east of the agonic line, then the variation is westward; magnetic north appears slightly west of the Geographic North Pole. If a navigator is west of the agonic line, then the variation is eastward; the Magnetic North Pole appears to the east of the Geographic North Pole. The farther the navigator is from the agonic line, the greater the variation. The local magnetic variation is indicated on NOAA nautical charts at the center of the compass rose. The magnetic variation is indicated along with the year of that variation. The annual increase or decrease of the variation is also usually indicated, so that the variation for the current year can be calculated.

Determine deviation

[edit]A compass installed in a vehicle or vessel has a certain amount of error caused by the magnetic properties of the vessel. This error is known as compass deviation. The magnitude of the compass deviation varies greatly depending upon the local anomalies created by the vessel. A fiberglass recreational vessel will generally have much less compass deviation than a steel-hulled vessel. Electrical wires carrying current have a small magnetic field around them and can cause deviation. Any type of magnet, such as found in a speaker can also cause large magnitudes of compass deviation. The error can be corrected using a deviation table. Deviation tables are very difficult to create. Once a deviation table is established, it is only good for that particular vessel, with that particular configuration. If electrical wires are moved or anything else magnetic (speakers, electric motors, etc.) are moved, the deviation table will change. All deviations in the deviation table are indicated west or east. If the compass is pointing west of the Magnetic North Pole, then the deviation is westward. If the compass is pointing east of the Magnetic North Pole, then the deviation is eastward.

Formula

[edit]Calculating TVMDC is done with simple arithmetic. First arrange the values vertically:

- True

- Variation

- Magnetic

- Deviation

- Compass

The formula is always added moving down, and subtracted when moving up. The most complicated part is determining if the values are positive or negative. The True, Magnetic, and Compass values are directions on the compass, they must always be a positive number between 0–360. Variation and Deviation can be positive or negative. If either Variation or Deviation is westward, then the values are entered into the equation as positive. If the Variation or Deviation is eastward, then the values are entered into the formula as a negative. Some use the mnemonic: True Virgins Make Dull Companions - Going downward Add Whiskey (or West). An alternative, working the opposite direction: Can Dead Men Vote Twice.

Examples

[edit]True course is 120°, the Variation is 5° West, and the Deviation is 1° West.

- T: 120°

- V: +5°

- M: 125°

- D: +1°

- C: 126°

Therefore, to achieve a true course of 120°, one should follow a compass heading of 126°.

True course is 120°, the Variation is 5° East and the Deviation is 1° East.

- T: 120°

- V: −5°

- M: 115°

- D: −1°

- C: 114°

True course is 035°, the Variation is 4° West and the Deviation is 1° East.

- T: 035°

- V: +4°

- M: 039°

- D: −1°

- C: 038°

True course is 306°, the Variation is 4° East and the Deviation is 11° West.

- T: 306°

- V: −4°

- M: 302°

- D: +11°

- C: 313°

Reverse

[edit]The formula can also be calculated in reverse. The formula is subtracted when moving up.

Compass course is 093°, the Deviation is 4° West and the Variation is 3° West.

- T: 086°

- V: -3°

- M: 089°

- D: -4°

- C: 093°

Thus, when following a compass course of 093°, the true course is 086°.

CDMVT

[edit]Aviation: CDMVT Can Dead Man Vote Twice: Mnemonic. Easy way to calculate compass magnetic or true north is maintaining the original signs for variation and deviation (+ for east and -for west): C+(Var)= M+(Dev)= T / T-(Dev)= M-(Var)= C

See also

[edit]- Bearing (navigation)

- Dead reckoning

- Heading indicator - Flight instrument

- Ship motions

Note

[edit]References

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]- Sea School (1977) True Virgins Make Dull Companions. Add Whiskey Going downward: Mnemonic

- Sweet, Robert J. (2004). The Weekend Navigator: Simple Boat Navigation With GPS and Electronics (Illustrated ed.). McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-07-143035-7.