Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Compass rose

View on Wikipedia

A compass rose or compass star, sometimes called a wind rose or rose of the winds, is a polar diagram displaying the orientation of the cardinal directions (north, east, south, and west) and their intermediate points. It is used on compasses (including magnetic ones), maps (such as compass rose networks), or monuments. It is particularly common in navigation systems, including nautical charts, non-directional beacons (NDB), VHF omnidirectional range (VOR) systems, satellite navigation devices ("GPS").

Types

[edit]Linguistic anthropological studies have shown that most human communities have four points of cardinal direction. The names given to these directions are usually derived from either locally-specific geographic features (e.g. "towards the hills", "towards the sea") or from celestial bodies (especially the sun) or from atmospheric features (winds, temperature).[1] Most mobile populations tend to adopt sunrise and sunset for East and West and the direction from where different winds blow to denote North and South.

Classical

[edit]The ancient Greeks originally maintained distinct and separate systems of points and winds. The four Greek cardinal points (arctos, anatole, mesembria and dusis) were based on celestial bodies and used for orientation. The four Greek winds (Boreas, Notos, Eurus, Zephyrus) were confined to meteorology. Nonetheless, both systems were gradually conflated, and wind names came eventually to denote cardinal directions as well.[2]

In his meteorological studies, Aristotle identified ten distinct winds: two north–south winds (Aparctias, Notos) and four sets of east–west winds blowing from different latitudes—the Arctic Circle (Meses, Thrascias), the summer solstice horizon (Caecias, Argestes), the equinox (Apeliotes, Zephyrus) and the winter solstice (Eurus, Lips). Aristotle's system was asymmetric. To restore balance, Timosthenes of Rhodes added two more winds to produce the classical 12-wind rose, and began using the winds to denote geographical direction in navigation. Eratosthenes deducted two winds from Aristotle's system, to produce the classical eight-wind rose.[citation needed]

The Romans (e.g. Seneca, Pliny) adopted the Greek 12-wind system, and replaced its names with Latin equivalents, e.g. Septentrio, Subsolanus, Auster, Favonius, etc. The De architectura of the Roman architect Vitruvius describes 24 winds.[3]

According to the chronicler Einhard (c. 830), the Frankish king Charlemagne himself came up with his own names for the classical 12 winds.[4] During the Migration Period, the Germanic names for the cardinal directions entered the Romance languages, where they replaced the Latin names borealis with north, australis with south, occidentalis with west and orientalis with east.[5]

The following table gives a rough equivalence of the classical 12-wind rose with the modern compass directions (The directions are imprecise since it is not clear at what angles the classical winds are supposed to be with each other; some have argued that they should be equally spaced at 30 degrees each; for more details, see the article on Classical compass winds).[citation needed]

| Wind | Greek | Roman | Frankish |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | Aparctias (ἀπαρκτίας) or Boreas (βoρέας) |

Septentrio | Nordroni |

| NNE | Meses (μέσης) | Aquilo | Nordostroni |

| NE | Caicias (καικίας) | Caecias | Ostnordroni |

| E | Apeliotes (ἀπηλιώτης) | Subsolanus | Ostroni |

| SE | Eurus (εὖρος) | Vulturnus | Ostsundroni |

| SSE | Euronotus (εὐρόνοτος) | Euronotus | Sundostroni |

| S | Notos (νότος) | Auster | Sundroni |

| SSW | Libonotos (λιβόνοτος) | Libonotus or Austroafricus |

Sundvuestroni |

| SW | Lips (λίψ) | Africus | Vuestsundroni |

| W | Zephyrus (ζέφυρος) | Favonius | Vuestroni |

| NW | Argestes (ἀργέστης) | Corus | Vuestnordroni |

| NNW | Thrascias (θρασκίας) | Thrascias or Circius | Nordvuestroni |

Sidereal

[edit]The sidereal compass rose demarcates the compass points by the position of stars ("steering stars"; not to be confused with zenith stars)[6] in the night sky, rather than winds. Arab navigators in the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean, who depended on celestial navigation, were using a 32-point sidereal compass rose before the end of the 10th century.[7][8][9] In the Northern Hemisphere, the steady Pole Star (Polaris) was used for the N–S axis; the less-steady Southern Cross had to do for the Southern Hemisphere, as the southern pole star, Sigma Octantis, is too dim to be easily seen from Earth with the naked eye. The other thirty points on the sidereal rose were determined by the rising and setting positions of fifteen bright stars. Reading from North to South, in their rising and setting positions, these are:[10]

| Point | Star |

|---|---|

| N | Polaris |

| NbE | "the Guards" (Ursa Minor) |

| NNE | Alpha Ursa Major |

| NEbN | Alpha Cassiopeiae |

| NE | Capella |

| NEbE | Vega |

| ENE | Arcturus |

| EbN | the Pleiades |

| E | Altair |

| EbS | Orion's belt |

| ESE | Sirius |

| SEbE | Beta Scorpionis |

| SE | Antares |

| SEbS | Alpha Centauri |

| SSE | Canopus |

| SbE | Achernar |

| S | Southern Cross |

The western half of the rose would be the same stars in their setting position. The true position of these stars is only approximate to their theoretical equidistant rhumbs on the sidereal compass. Stars with the same declination formed a "linear constellation" or kavenga to provide direction as the night progressed.[11]

A similar sidereal compass was used by Polynesian and Micronesian navigators in the Pacific Ocean, although different stars were used in a number of cases, clustering around the east–west axis.[12][6]

Mariner's

[edit]In Europe, the Classical 12-wind system continued to be taught in academic settings during the Medieval era, but seafarers in the Mediterranean came up with their own distinct 8-wind system. The mariners used names derived from the Mediterranean lingua franca, composed principally of Ligurian, mixed with Venetian, Sicilian, Provençal, Catalan, Greek and Arabic terms from around the Mediterranean basin.

- (N) Tramontana

- (NE) Greco (or Bora)

- (E) Levante

- (SE) Scirocco (or Exaloc)

- (S) Ostro (or Mezzogiorno)

- (SW) Libeccio (or Garbino)

- (W) Ponente

- (NW) Maestro (or Mistral)

The exact origin of the mariner's eight-wind rose is obscure. Only two of its point names (Ostro, Libeccio) have Classical etymologies, the rest of the names seem to be autonomously derived. Two Arabic words stand out: Scirocco (SE) from al-Sharq (الشرق – east in Arabic) and the variant Garbino (SW), from al-Gharb (الغرب – west in Arabic). This suggests the mariner's rose was probably acquired by southern Italian seafarers; not from their classical Roman ancestors, but rather from Norman Sicily in the 11th to 12th centuries.[13] The coasts of the Maghreb and Mashriq are SW and SE of Sicily respectively; the Greco (a NE wind), reflects the position of Byzantine-held Calabria-Apulia to the northeast of Arab Sicily, while the Maestro (a NW wind) is a reference to the Mistral wind that blows from the southern French coast towards northwest Sicily.[citation needed]

The 32-point compass used for navigation in the Mediterranean by the 14th century, had increments of 111⁄4° between points. Only the eight principal winds (N, NE, E, SE, S, SW, W, NW) were given special names. The eight half-winds just combined the names of the two principal winds, e.g. Greco-Tramontana for NNE, Greco-Levante for ENE, and so on. Quarter-winds were more cumbersomely phrased, with the closest principal wind named first and the next-closest principal wind second, e.g. "Quarto di Tramontana verso Greco" (literally, "one quarter wind from North towards Northeast", i.e. North by East), and "Quarto di Greco verso Tramontana" ("one quarter wind from NE towards N", i.e. Northeast by North). Boxing the compass (naming all 32 winds) was expected of all Medieval mariners.[citation needed]

Depiction on nautical charts

[edit]In the earliest medieval portolan charts of the 14th century, compass roses were depicted as mere collections of color-coded compass rhumb lines: black for the eight main winds, green for the eight half-winds and red for the sixteen quarter-winds.[14] The average portolan chart had sixteen such roses (or confluence of lines), spaced out equally around the circumference of a large implicit circle.

The cartographer Cresques Abraham of Majorca, in his Catalan Atlas of 1375, was the first to draw an ornate compass rose on a map. By the end of the 15th century, Portuguese cartographers began drawing multiple ornate compass roses throughout the chart, one upon each of the sixteen circumference roses (unless the illustration conflicted with coastal details).[15]

The points on a compass rose were frequently labeled by the initial letters of the mariner's principal winds (T, G, L, S, O, L, P, M). From the outset, the custom also began to distinguish the north from the other points by a specific visual marker. Medieval Italian cartographers typically used a simple arrowhead or circumflex-hatted T (an allusion to the compass needle) to designate the north, while the Majorcan cartographic school typically used a stylized Pole Star for its north mark.[16] The use of the fleur-de-lis as north mark was introduced by Pedro Reinel, and quickly became customary in compass roses (and is still often used today). Old compass roses also often used a Christian cross at Levante (E), indicating the direction of Jerusalem from the point of view of the Mediterranean sea.[17]

The twelve Classical winds (or a subset of them) were also sometimes depicted on portolan charts, albeit not on a compass rose, but rather separately on small disks or coins on the edges of the map.

The compass rose was also depicted on traverse boards used on board ships to record headings sailed at set time intervals.

-

Early 32-wind compass rose, shown as a mere collection of color-coded rhumblines, from a Genoese nautical chart (c. 1325)

-

First ornate compass rose depicted on a chart, from the Catalan Atlas (1375), with the Pole Star as north mark

-

More ornate compass rose, with letters of traditional winds, a cross pattée (referring to Jerusalem) for east, and a compass needle as north mark, from a nautical chart by Jorge de Aguiar (1492)

-

Highly ornate compass rose, with fleur-de-lis as north mark and cross pattée as east mark, from the Cantino planisphere (1502)

Modern depictions

[edit]

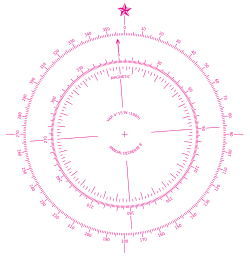

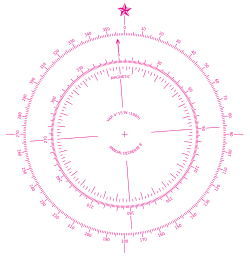

The contemporary compass rose appears as two rings, one smaller and set inside the other. The outside ring denotes true cardinal directions while the smaller inside ring denotes magnetic cardinal directions. True north refers to the geographical location of the North Pole while magnetic north refers to the direction towards which the north pole of a magnetic object (as found in a compass) will point. The angular difference between true and magnetic north is called variation, which varies depending on location.[18] The angular difference between magnetic heading and compass heading is called deviation which varies by vessel and its heading. North arrows are often included in contemporary maps as part of the map layout. The modern compass rose has eight principal winds. Listed clockwise, these are:

| Compass point | Abbr. | Heading | Traditional wind |

|---|---|---|---|

| North | N | 0° | Tramontana |

| North-east | NE | 45° (45°×1) | Greco or Grecale |

| East | E | 90° (45°×2) | Levante |

| South-east | SE | 135° (45°×3) | Scirocco |

| South | S | 180° (45°×4) | Ostro or Mezzogiorno |

| South-west | SW | 225° (45°×5) | Libeccio or Garbino |

| West | W | 270° (45°×6) | Ponente |

| North-west | NW | 315° (45°×7) | Maestro or Mistral |

Although modern compasses use the names of the eight principal directions (N, NE, E, SE, etc.), older compasses use the traditional Italianate wind names of Medieval origin (Tramontana, Greco, Levante, etc.).

Four-point compass roses use only the four "basic winds" or "cardinal directions" (North, East, South, West), with angles of difference at 90°.

Eight-point compass roses use the eight principal winds—that is, the four cardinal directions (N, E, S, W) plus the four "intercardinal" or "ordinal directions" (NE, SE, SW, NW), at angles of difference of 45°.

Twelve-point compass roses, with markings 30° apart, are often painted on airport ramps to assist with the adjustment of aircraft magnetic compass compensators.[19]

Sixteen-point compass roses are constructed by bisecting the angles of the principal winds to come up with intermediate compass points, known as half-winds, at angles of difference of 221⁄2°. The names of the half-winds are simply combinations of the principal winds to either side, principal then ordinal. E.g. North-northeast (NNE), East-northeast (ENE), etc. Using gradians, of which there are 400 in a circle,[20] the sixteen-point rose has twenty-five gradians per point.

Thirty-two-point compass roses are constructed by bisecting these angles, and coming up with quarter-winds at 111⁄4° angles of difference. Quarter-wind names are constructed with the names "X by Y", which can be read as "one quarter wind from X toward Y", where X is one of the eight principal winds and Y is one of the two adjacent cardinal directions. For example, North-by-east (NbE) is one quarter wind from North towards East, Northeast-by-north (NEbN) is one quarter wind from Northeast toward North. Naming all 32 points on the rose is called "boxing the compass".

The 32-point rose has 111⁄4° between points, but is easily found by halving divisions and may have been easier for those not using a 360° circle. Eight points make a right angle and a point is easy to estimate allowing bearings to be given such as "two points off the starboard bow".[21]

-

A 4-point compass rose

-

An 8-point compass rose

-

A 16-point compass rose

-

A 32-point compass rose

-

A 360 degree and 6400 NATO mil compass rose

Use as symbol

[edit]- The NATO symbol uses a four-pointed rose.

- Outward Bound uses the compass rose as the logo for various schools around the world.

- An 8-point compass rose was the logo of Varig, the largest airline in Brazil for many decades until its bankruptcy in 2006.

- An 8-point compass rose is a prominent feature in the logo of the Seattle Mariners Major League Baseball club.

- Hong Kong Correctional Services's crest uses a four-pointed compass rose.

- The compass rose is used as the symbol of the worldwide Anglican Communion of churches.[22]

- A 16-point compass rose was IBM's logo for the System/360 product line.

- A 16-point compass rose is the official logo of the Spanish National University of Distance Education (Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia or UNED).[23]

- A 16-point compass rose is present on the seal and the flag of the Central Intelligence Agency of the federal government of the United States (the CIA).

- Tattoos of eight-pointed stars are used by the Vor v Zakone to denote rank.

- The rationality-focused community blog LessWrong uses a compass rose as its logo.[24]

In popular culture

[edit]- The Compass Rose is a 1982 collection of short stories by Ursula K. Le Guin.[25]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Brown, C.H. (1983) "Where do Cardinal Direction Terms Come From?", Anthropological Linguistics, Vol. 25 (2), pp. 121–61.

- ^ D'Avezac, M.A.P. (1874) Aperçus historiques sur la rose des vents: lettre à Monsieur Henri Narducci. Rome: Civelli

- ^ Ulrike Passe and Francine Battaglia (2015). Designing Spaces for Natural Ventilation: An Architect's Guide. Taylor & Francis. p. 76. ISBN 9781136664823.

- ^ Einhard, Vita Karoli Imp., [Lat: (Eng.(p. 22)(p. 68)

- ^ See e.g. Weibull, Lauritz. De gamle nordbornas väderstrecksbegrepp. Scandia 1/1928; Ekblom, R. Alfred the Great as Geographer. Studia Neophilologica 14/1941-2; Ekblom, R. Den forntida nordiska orientering och Wulfstans resa till Truso. Förnvännen. 33/1938; Sköld, Tryggve. Isländska väderstreck. Scripta Islandica. Isländska sällskapets årsbok 16/1965.

- ^ a b Lewis, David (1972). "We, the navigators : the ancient art of landfinding in the Pacific". Australian National University Press. Retrieved June 1, 2023.

- ^ Saussure, L. de (1923) "L'origine de la rose des vents et l'invention de la boussole", Archives des sciences physiques et naturelles, vol. 5, no.2 & 3, pp. 149–81 and 259–91.

- ^ Taylor, E.G.R. (1956) The Haven-Finding Art: A history of navigation from Odysseus to Captain Cook, 1971 ed., London: Hollis and Carter., pp. 128–31.

- ^ Tolmacheva, M. (1980) "On the Arab System of Nautical Orientation", Arabica, vol. 27 (2), pp. 180–92.

- ^ List comes from Tolmacheva (1980:p. 183), based "with some reservations" on Tibbets (1971: p. 296, n. 133). The sidereal rose given in Lagan (2005: p. 66) has some differences, e.g. placing Orion's belt in East and Altair in EbN.

- ^ M.D. Halpern (1985) The Origins of the Carolinian Sidereal Compass, Master's thesis, Texas A & M University

- ^ Goodenough, W. H. (1953). Native Astronomy in the Central Carolines. Philadelphia: University Museum, University of Philadelphia. p. 3.

- ^ Taylor, E.G. R. (1937) "The 'De Ventis' of Matthew Paris", Imago Mundi, vol. 2, p. 25.

- ^ Wallis, H.M. and J.H. Robinson, editors (1987) Cartographical Innovations: An international handbook of mapping terms to 1900. London: Map Collector Publications.

- ^ Mill, Hugh Robert (1896). Report of the Sixth International Geographical Congress: Held in London, 1895. J. Murray.

- ^ Winter, Heinrich (1947) "On the Real and the Pseudo-Pilestrina Maps and Other Early Portuguese Maps in Munich", Imago Mundi, vol. 4, pp. 25–27.

- ^ Dan Reboussin (2005). Wind Rose. Archived 2016-09-01 at the Wayback Machine University of Florida. Retrieved on 2009-04-26.

- ^ John Rousmaniere; Mark Smith (1999). The Annapolis book of seamanship. Simon and Schuster. p. 233. ISBN 978-0-684-85420-5. Retrieved July 7, 2011.

- ^ Pilot's Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge (PDF). Federal Aviation Administration. 2016. pp. 8–25. Retrieved November 18, 2019.

- ^ Patrick Bouron (2005). Cartographie: Lecture de Carte (PDF). Institut Géographique National. p. 12. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 15, 2010. Retrieved July 7, 2011.

- ^ Underwood, Tracy (2021). "Two Points Off Starboard Bow Definition". Gone Outdoors. Retrieved October 26, 2021.

- ^ "About the Compass Rose Society". Compassrosesociety.org. Archived from the original on October 7, 2011. Retrieved December 18, 2011.

- ^ "Descripción del Escudo de la UNED (Description of the UNED emblem)". Archived from the original on January 13, 2014. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ "Why do we have the NATO logo?". LessWrong. Retrieved May 26, 2025.

- ^ "Locus Awards Nominee List". The Locus Index to SF Awards. Archived from the original on May 14, 2012. Retrieved May 12, 2011.

External links

[edit]- The Rose of the Winds, an example of a rose with 26 directions.

- Compass Rose of Piedro Reinel, 1504, an example of a 32-point rose with cross for east (the Christian Holy Land) and fleur-di-lis for north (do find for "Reinel").

- The Compass Rose in St. Peter's Square

- Brief compass rose history info

- Floor Compass Roses

- Quilting Patterns Inspired by Compass Rose

- Compass Rose in Stained Glass