Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Tabula recta

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2014) |

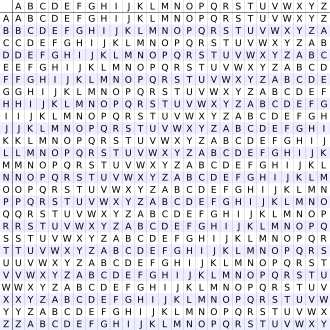

In cryptography, the tabula recta (from Latin tabula rēcta) is a square table of alphabets, each row of which is made by shifting the previous one to the left. The term was invented by the German author and monk Johannes Trithemius[1] in 1508, and used in his Trithemius cipher.

Trithemius cipher

[edit]The Trithemius cipher was published by Johannes Trithemius in his book Polygraphia, which is credited with being the first published printed work on cryptology.[2]

Trithemius used the tabula recta to define a polyalphabetic cipher, which was equivalent to Leon Battista Alberti's cipher disk except that the order of the letters in the target alphabet is not mixed. The tabula recta is often referred to in discussing pre-computer ciphers, including the Vigenère cipher and Blaise de Vigenère's less well-known autokey cipher. All polyalphabetic ciphers based on the Caesar cipher can be described in terms of the tabula recta.

The tabula recta uses a letter square with the 26 letters of the alphabet followed by 26 rows of additional letters, each shifted once to the left from the one above it. This, in essence, creates 26 different Caesar ciphers.[1]

The resulting ciphertext appears as a random string or block of data. Due to the variable shifting, natural letter frequencies are hidden. However, if a codebreaker is aware that this method has been used, it becomes easy to break. The cipher is vulnerable to attack because it lacks a key, thus violating Kerckhoffs's principle of cryptology.[1]

Improvements

[edit]In 1553, an important extension to Trithemius's method was developed by Giovan Battista Bellaso, now called the Vigenère cipher.[3] Bellaso added a key, which is used to dictate the switching of cipher alphabets with each letter. This method was misattributed to Blaise de Vigenère, who published a similar autokey cipher in 1586.

The classic Trithemius cipher (using a shift of one) is equivalent to a Vigenère cipher with ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ as the key. It is also equivalent to a Caesar cipher in which the shift is increased by 1 with each letter, starting at 0.

Usage

[edit]Within the body of the tabula recta, each alphabet is shifted one letter to the left from the one above it. This forms 26 rows of shifted alphabets, ending with an alphabet starting with Z (as shown in image). Separate from these 26 alphabets are a header row at the top and a header column on the left, each containing the letters of the alphabet in A-Z order.

The tabula recta can be used in several equivalent ways to encrypt and decrypt text. Most commonly, the left-side header column is used for the plaintext letters, both with encryption and decryption. That usage will be described herein. In order to decrypt a Trithemius cipher, one first locates in the tabula recta the letters to decrypt: first letter in the first interior column, second letter in the second column, etc.; the letter directly to the far left, in the header column, is the corresponding decrypted plaintext letter. Assuming a standard shift of 1 with no key used, the encrypted text HFNOS would be decrypted to HELLO (H->H, F->E, N->L, O->L, S->O ). So, for example, to decrypt the second letter of this text, first find the F within the second interior column, then move directly to the left, all the way to the leftmost header column, to find the corresponding plaintext letter: E.

Data is encrypted in the opposite fashion, by first locating each plaintext letter of the message in the leftmost header column of the tabula recta, and mapping it to the appropriate corresponding letter in the interior columns. For example, the first letter of the message is found within the left header column, and then mapped to the letter directly across in the column headed by "A". The next letter is then mapped to the corresponding letter in the column headed by "B", and this continues until the entire message is encrypted.[4] If the Trithemius cipher is thought of as having the key ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ, the encryption process can also be conceptualized as finding, for each letter, the intersection of the row containing the letter to be encrypted with the column corresponding to the current letter of the key. The letter where this row and column cross is the ciphertext letter.

Programmatically, the cipher is computable, assigning , then the encryption process is . Decryption follows the same process, exchanging ciphertext and plaintext. key may be defined as the value of a letter from a companion ciphertext in a running key cipher, a constant for a Caesar cipher, or a zero-based counter with some period in Trithemius's usage.[5]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c Salomon, Data Privacy, page 63

- ^ Kahn, David (1996). The Codebreakers (2nd ed.). Scribner. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-684-83130-5.

- ^ Salomon, Coding for Data, page 249

- ^ Rodriguez-Clark, Dan, Polyalphabetic Substitution Ciphers, Crypto Corner

- ^ Kahn, page 136

Sources

[edit]- Salomon, David (2005). Coding for Data and Computer Communications. Springer. ISBN 0-387-21245-0.

- Salomon, David (2003). Data Privacy and Security. Springer. ISBN 0-387-00311-8.

- King, Francis X. (1989). Modern Ritual Magic: The Rise of Western Occultism (2nd ed.). Prism Press. ISBN 1-85327-032-6.

- Kahn, David (1996). The Codebreakers. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-684-83130-9.

External links

[edit]- Encrypting a secret text with the Vigenère cipher and the Tabula recta on YouTube - A video that shows and explains how to use the Tabula recta for the Vigenère cipher

Tabula recta

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Construction

Overview

The tabula recta is a 26×26 Latin square table employed in cryptography for the English alphabet, with rows and columns labeled A through Z, where each cell contains a letter from an alphabet shifted progressively one position to the left in a cyclic manner.[4] This structure represents modular arithmetic operations on letters, enabling direct substitution without converting to numbers.[4] Its primary purpose is to facilitate polyalphabetic substitution ciphers, where a key determines the row used for each plaintext letter, generating a sequence of distinct substitution alphabets to obscure the message and resist simple frequency analysis.[5] By providing 26 unique alphabets—one for each letter position—the table enhances encryption complexity, as each plaintext character can map to multiple possible ciphertext letters depending on the key-derived row.[6] Visually, the table is symmetric across its main diagonal, with each subsequent row representing a cyclic shift of the alphabet by one position, creating a grid for addition of letter values modulo 26.[4] For example, to encrypt the plaintext letter A against a key letter B, one locates the B row and A column intersection, which yields B as the ciphertext letter, allowing straightforward letter-by-letter processing.[6]Building the Table

The tabula recta is constructed as an n × n square table, where n is the number of letters in the alphabet, most commonly 26 for the modern English alphabet.[7] The table consists of n rows, each representing a shifted version of the alphabet, enabling efficient lookups for polyalphabetic substitutions.[7] To build the table step by step, begin with the top row (often labeled with the plaintext letters across the columns) filled with the standard alphabet in order: A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z.[7] The second row starts with B and continues with C through Z, followed by A at the end, effectively shifting the entire alphabet one position to the left in a circular manner.[7] Each subsequent row applies the same leftward circular shift to the previous row, incrementing the shift by one position per row until the final row returns to the original alphabet order but shifted fully (Z A B ... Y).[7] This progressive shifting ensures no letter repeats within any row or column, resulting in a Latin square structure that guarantees unique substitutions.[8] For alphabets smaller than 26 letters, such as classical Latin versions with 23 letters (excluding J, U, W) or Trithemius's 24-letter adaptation, the table is scaled accordingly by applying the same circular shift method to the reduced set.[7][9] Alternative circular shift directions (e.g., rightward) can be used, but the standard left shift maintains the Latin square property as long as shifts are uniform and wrap around without repetition.[7] The following partial example illustrates the first three rows and columns for a 26-letter alphabet (rows labeled on the left, columns across the top):| A | B | C | D | E | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | A | B | C | D | E |

| B | B | C | D | E | A |

| C | C | D | E | A | B |

Historical Origins

Trithemius's Invention

Johannes Trithemius (1462–1516), a German Benedictine abbot and polymath, served as the abbot of the Sponheim monastery and pursued scholarly interests spanning lexicography, chronology, and the occult sciences, including the arcane arts of secret writing and steganography.[10][11] His fascination with concealed communication reflected broader Renaissance explorations of hidden knowledge, blending cryptographic techniques with mystical and esoteric traditions.[11] In 1508, Trithemius devised the tabula recta as a foundational tool in his cryptographic innovations, aiming to transcend the vulnerabilities of earlier monoalphabetic methods such as the Caesar cipher's fixed shifts.[12][13] This square table of alphabets enabled more sophisticated substitution schemes, serving as the basis for his progressive cipher system.[13] Trithemius's primary motivation was to engineer dynamic encryption that evolved across the message's length, incorporating a running key derived from the sequential position of each letter to produce varying substitutions and thereby increase resistance to frequency analysis.[10] By shifting the alphabet progressively—starting with minimal displacement and incrementing it for each subsequent character—his approach sought to mimic natural language variability while ensuring systematic security.[13] The tabula recta initially emerged in unpublished manuscripts of Trithemius's Polygraphia, completed that same year, where it underpinned demonstrations of these progressive techniques before the work's posthumous publication a decade later.[10][12]Publication and Early Context

The Tabula recta, a key cryptographic tool, was first introduced to the public in Johannes Trithemius's Polygraphia, a comprehensive treatise on steganography and cryptography composed around 1508 and published posthumously in 1518 in Basel by his admirers.[10] This work, spanning six books, systematically explored various forms of secret writing, including substitution ciphers, and presented the tabula recta as a tabular method for generating multiple alphabets to enhance message security.[14][15] Dedicated to Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I, the volume marked the inaugural printed book on cryptology in the Western world, reflecting Trithemius's intent to formalize the art for practical and scholarly use.[16] The publication occurred amid the Renaissance's burgeoning fascination with codes and ciphers, driven by humanist scholarship's emphasis on classical texts and the era's political-religious tensions. Humanists like Trithemius, who engaged in learned societies in Heidelberg, sought to revive ancient knowledge while navigating fears of ecclesiastical and imperial censorship, particularly as the Protestant Reformation loomed and sensitive diplomatic correspondences required concealment.[17] Cryptography thus served not only military and state purposes but also as a safeguard for intellectual exchange in an age of inquisitorial scrutiny and fragmented principalities.[16] Early reception of Polygraphia was confined largely to elite scholarly and clerical circles, owing to its composition in Latin and the esoteric nature of its content, which blended practical cryptography with allusions to hidden knowledge. While the book achieved notable circulation among European intellectuals—evidenced by its elegant folio format and references in subsequent cryptographic treatises—its complexity and Trithemius's controversial reputation limited broader dissemination beyond monasteries and courts. Misattributions arose from the author's association with occultism, leading some to view the work suspiciously despite its overt focus on secular ciphers, though it avoided the outright suppression faced by more arcane texts.[18][11] Polygraphia complemented Trithemius's earlier Steganographia (written circa 1499–1500 but unpublished until 1606), which disguised cryptographic techniques within a framework of angelic magic and invocations, reflecting the author's dual interest in concealment and the esoteric. Unlike the more guarded Steganographia, which circulated in manuscript and was later condemned for sorcery, Polygraphia offered an explicit, non-occult exposition of similar principles, positioning the tabula recta as a foundational element in the evolution of steganographic arts.[19][11]Cryptographic Applications

Trithemius Cipher

The Trithemius cipher is a polyalphabetic substitution cipher that employs the tabula recta to generate a progressive keystream based on the position of each letter in the plaintext message.[20] In this system, the rows of the tabula recta serve as successive ciphertext alphabets, with the first row (starting with A) used for the first plaintext letter, the second row (starting with B) for the second, and so on, wrapping around after Z if the message exceeds 26 letters.[21] This position-dependent selection creates a deterministic keystream equivalent to adding an incrementing shift (0 for the first letter, 1 for the second, etc.) to each plaintext letter's position in the alphabet, modulo 26.[22] To encrypt a message, prepare the plaintext in uppercase without spaces or punctuation, then for each letter at position i (starting from 1), locate the plaintext letter along the top row of the tabula recta and find the intersection with the i-th row (labeled A for i=1, B for i=2, etc.) to obtain the ciphertext letter.[21] Decryption reverses this by using the same positional rows but subtracting the shift: for each ciphertext letter at position i, find it in the i-th row and read the corresponding letter in the top row (plaintext alphabet).[22] For example, consider the plaintext "ATTACKATDAWN" (12 letters, all uppercase). The positional shifts are 0 through 11:- A (position 1, shift 0): remains A

- T (2, 1): shifts to U

- T (3, 2): shifts to V

- A (4, 3): shifts to D

- C (5, 4): shifts to G

- K (6, 5): shifts to P

- A (7, 6): shifts to G

- T (8, 7): shifts to A

- D (9, 8): shifts to L

- A (10, 9): shifts to J

- W (11, 10): shifts to G

- N (12, 11): shifts to Y

Vigenère and Related Ciphers

The Vigenère cipher, first described by Italian cryptologist Giovan Battista Bellaso in his 1553 treatise La cifra del. Sig. Giovan Battista Bellaso, represents a key advancement in using the tabula recta for polyalphabetic encryption by incorporating a repeating keyword to dynamically select substitution alphabets. Unlike earlier positional methods, the keyword—such as "KEY"—repeats to match the plaintext length, with each key letter determining the row of the tabula recta. The plaintext letter is then aligned with the column headers, and the ciphertext is read from the intersection. This approach provides greater flexibility and security by avoiding fixed progressions, as the key can be any length and repeated as needed.[20] To illustrate encryption, consider the plaintext "HELLO" and keyword "KEY" (repeated as "KEYKE" to match length). Assuming a standard 26-letter English alphabet tabula recta:- For 'H' (plaintext) and 'K' (key): Locate row 'K' (shifted alphabet starting K, L, M, ..., J) and column 'H'; the intersection yields 'R'.

- For 'E' and 'E': Row 'E' (E, F, G, ..., D) and column 'E' yields 'I'.

- For 'L' and 'Y': Row 'Y' (Y, Z, A, ..., X) and column 'L' yields 'J'.

- For 'L' and 'K': Row 'K' and column 'L' yields 'V'.

- For 'O' and 'E': Row 'E' and column 'O' yields 'S'.