Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Techniscope

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2023) |

Techniscope or 2-perf is a 35 mm motion picture camera film format introduced by Technicolor Italia in 1960.[1] The Techniscope format uses a two film-perforation negative pulldown per frame, instead of the standard four-perforation frame usually exposed in 35 mm film photography. Techniscope's 2.33:1 aspect ratio is easily enlarged to the 2.39:1 widescreen ratio,[2] because it uses half the amount of 35 mm film stock and standard spherical lenses. Thus, Techniscope release prints are made by anamorphosing, enlarging each frame vertically by a factor of two.

Techniscope-photographed films

[edit]During its primary reign of 1960–1980, more than 350 films were photographed in Techniscope,[3] the first of which was The Pharaoh's Woman, released 10 December 1960.[4] Given its considerable savings in production cost but lower image quality, Techniscope was primarily an alternative format used for the production of lower-budgeted films, mainly those in the horror and western genres. It also is useful for films using many miniatures such as the Gerry Anderson puppet production Thunderbirds Are Go as this format gives increased depth of focus without requiring huge amounts of light required when the aperture is made very small. Since the format originated in Italy, most Techniscope format films were European productions.[vague]

In the U.S., Techniscope was used in the low-budget A.C. Lyles Westerns for Paramount Pictures, as well as in a few Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer pictures, and Universal Studios briefly used it extensively in the mid-to-late 1960's. The Sergio Leone “Dollars Trilogy” films used Techniscope, (Fistful of Dollars, For a Few Dollars More and The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly) and were released through United Artists.[5] Producer Sid Pink recalled that unlike Europe, the American film studios were charged by the Technicolor company for using Techniscope in their film prints.[6] George Lucas shot his first two features, THX 1138 and American Graffiti, in Techniscope in order to give them a gritty, documentary-like feel.[7]

Regarding the diminished image quality, film reviewer Roger Ebert wrote about the film Counterpoint (1968): "The movie is shot in Techniscope, a process designed to give a wide-screen picture while saving film and avoiding payment of royalties to the patented processes like Panavision. In this film, as in Harry Frigg, Techniscope causes washed-out color and a loss of detail. Universal shouldn't be so cheap."[8]

Films shot with 2-perf 35 mm "Techniscope" since 2010 include I'm Yours (2012), Silver Linings Playbook (2012), Argo (2012), and Too Late (2015).

Techniscope's commercial revival

[edit]Techniscope employs standard 35 mm camera films, which are suitable for 2-perf (Techniscope), 3-perf, conventional 4-perf (spherical or CinemaScope), and even 6-perf (Cinerama) and 8-perf (VistaVision), as all of those processes listed employ the same width negative and intermediate films, and positive print films intended for direct projection (although 2-, 3- and 8-perfs are not distribution formats).

In 1999, in Australia, MovieLab film laboratory owner Kelvin Crumplin revived the Techniscope format renamed as MultiVision 235, attempting to commercialise it as a cinematography format alternative to the Super 16 mm format. His proposition was that it yielded a 35 mm-quality image (from which could be derived natural 2.35:1 and 1.85:1 aspect ratio images) for the same cost as Super 16 mm cinematography.

Mr Crumplin established MovieLab to provide telecine and film processing and printing services, and, with engineer Bruce McNaughton of The Aranda Group, Victoria, Australia, engineered and produced Arriflex BL1 and Arriflex IIC 35 mm cameras for the Techniscope 2-perf format.[3]

Aaton, Panavision, and Arriflex have modern 2-perf cameras. Aranda in Australia is also currently converting cameras like Arriflex 2A/B/C Arri 3, Arri BL, Mitchell, Eclair, Moviecam. The Russian cameras, Kinor and Konvas, are also converted.

Factory-made kits for certain Mitchell and Mitchell-derived cameras are occasionally available on auction sites. In the specific case of a Mitchell, the kit includes a replacement aperture plate and cam for the film movement, a replacement gear for the camera body, and, for a reflex camera, a replacement focusing screen. As all Mitchell cameras incorporate the provision for a "hard mask" within the movement itself, it is often possible to keep the 4-perf aperture plate, and insert a 2-perf mask in the mask slot, as an economy measure.

In 2011, Lomography released a movie camera, the Lomokino, capable of making short movies on standard 35 mm still photography film which uses a frame format similar to Techniscope, with two perforations for each exposure, though with no space or capabilities for the sound track, taking 144 frames on a 36 exposure roll. The camera is erroneously labeled as being "Super 35", Super 35 having four perforations per frame. Movies made with the Lomokino may not show properly without modifications on Techniscope projectors, the Lomokino is hand cranked and the frame rate is controlled manually, usually being around 2-6 FPS.

Techniscope vs. anamorphic: advantages and disadvantages

[edit]Techniscope's advantages over anamorphic CinemaScope are:

- More economical: half the film stock used in 4-perforation frame cinematography; half the stock, same running time, less negative to develop.

- Cinematography uses simpler, but technically superior, spherical lenses.

- Film stock loads last twice as long; 2-perf stock shoots at 45 feet per minute, while 4-perf stock shoots at 90 feet per minute.

- (may be seen aesthetically as either an advantage or disadvantage:) The circle of confusion of Techniscope is circular (due to its spherical lenses), whereas that of CinemaScope is elliptical (due to its anamorphic lenses).

Techniscope's disadvantages against CinemaScope:

- Two-perf 35 mm is a production-only format, that must be converted to other formats for distribution. For distribution prints for theatrical venues, the frame is enlarged from a 2-perf flat ratio to a 4-perf anamorphic ratio. Enlarging the image to the 35 mm print subsequently enlarges the negative's film grain. (Although some cineastes sought this visual feel for the story; e.g. westerns photographed to appear unpolished, thereby enhancing the period settings' verisimilitude.) This step is also an additional production expense. If the enlargement process is done optically, the generation loss will add even more grain and reduce the image sharpness. Alternatively, the enlargement can be done as part of the digital intermediate (DI) process. This involves digitally scanning the 2-perf film negative. Output to film is done with a film recorder, such as the Arrilaser.

- Two-perforation cameras and telecine installations are rare. (Note: As of early 2008 Aaton is coming out with their newly designed 2-perf-native (3-perf user-switchable) Aaton Penelope camera. Konvas cameras have been available in 2-perf for a while, and Arri is making 2-perf gates for their Arricams soon, available only through the rental dealers though. And more and more telecine suites have 2-perf gates for their film scanners.)

- The narrower frame line (between frames) emphasises imperfections (e.g. hairs in the gate, lens flares).[clarification needed]

Note: When transferring a Techniscope film to a digital video format, the 2-perf negative or 2-perf interpositive A/B rolls can be used (the original film negative from the camera, or the first-generation film elements prepared for the making of the anamorphic 4-frame 35 mm release print negative), thus bypassing any blown-up 4-perf element. Many DVD editions have been transferred this way and the results have frequently been stunning, e.g. Blue Underground's The Bird with the Crystal Plumage and MGM's special editions of Sergio Leone's Westerns.

Specifications

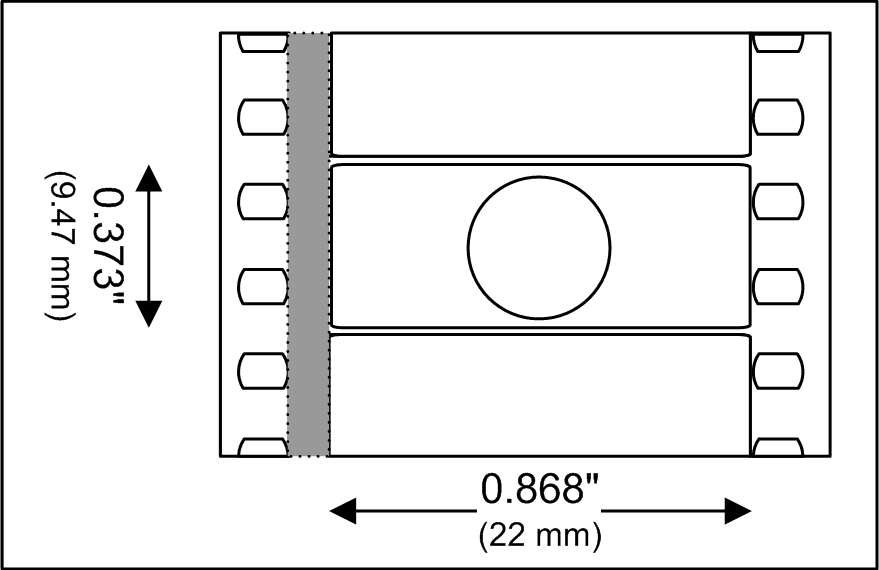

[edit]- Film: 35 mm film running vertically using two perforations per frame, running at 24 frames per second.

- Film area: 0.868 in × 0.373 in (22.0 mm × 9.5 mm)

- Film aspect ratio: 2.33:1

- Print aspect ratio 2.39:1 (2.35:1 prior to 1970 SMPTE revision)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Konigsberg, Ira (1987). The Complete Film Dictionary Meridian / NAL Books p.372. ISBN 0-452-00980-4

- ^ NOTE: In 1970, the SMPTE revised the 2.35:1 aspect ratio to 2.39:1 for projection, however, before standardization, most Techniscope films were photographed and released in the 2.35:1 aspect ratio

- ^ a b Holben, Jay & Bankston, Douglas (February 2000). "Inventive New Options for Film" American Cinematographer Magazine Vol. 81, No. 2, pp.96–107.

- ^ The Pharaoh's Woman at IMDb—retrieved 19 March 2007

- ^ "The American Widescreen Museum - TECHNISCOPE - American Cinematographer Article". Archived from the original on 4 July 2018. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- ^ p.194 Pink, Sidney So You Want to Make Movies: My Life as an Independent Film Producer Pineapple Press, 1989

- ^ Jones, Brian Jay George Lucas: A Life Little/Brown, 2016

- ^ "Roger Ebert, Chicago Sun-Times review for Counterpoint". Archived from the original on 17 November 2006. Retrieved 14 July 2006.