Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Trail Making Test

View on Wikipedia| Trail Making Test | |

|---|---|

Part A sample | |

| MeSH | D014145 |

The Trail Making Test is a neuropsychological test of visual attention and task switching. It has two parts, in which the subject is instructed to connect a set of 25 dots as quickly as possible while maintaining accuracy.[1] The test can provide information about visual search speed, scanning, speed of processing, mental flexibility, and executive functioning.[1] It is sensitive to cognitive impairment associated with dementia, including Alzheimer's disease.[2]

History

[edit]The test was created by Ralph Reitan, an American neuropsychologist considered one of the fathers of clinical neuropsychology. The test was used in 1944 for assessing general intelligence, and was part of the Army Individual Test of General Ability.[3] In the 1950s[4][5] researchers began using the test to assess cognitive dysfunction stemming from brain damage, and it has since been incorporated into the Halstead–Reitan battery.[3] The Trail Making Test is now commonly used as a diagnostic tool in clinical settings. Poor performance is known to be associated with many types of brain impairment, in particular frontal lobe lesion.

Method and interpretation

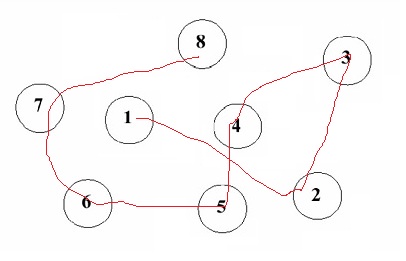

[edit]The task requires the subject to connect 25 consecutive targets on a sheet of paper or a computer screen, in a manner to like that employed in connect-the-dots exercises. There are two parts to the test. In the first, the targets are all the whole numbers from 1 to 25, and the subject must connect them in numerical order. In the second part, thirteen of the dots are numbered from 1 to 13 and twelve are given the letters from A to L; the subject must connect the dots in order while alternating letters and numbers (1–A–2–B–3–C ...) as fast as possible without lifting the pen from the paper.[6] If the subject makes an error, the test administrator corrects it before the subject moves to the next dot.[6]

The goal of the test is for the subject to finish both parts as quickly as possible, with the time taken to complete the test being used as the primary performance metric. The error rate is not recorded in the paper version of the test; instead, time spent correcting errors extends the completion time.[3] The second part of the test, in which the subject alternates between numbers and letters, is used to examine executive functioning.[3] The first part is used primarily to examine cognitive processing speed.[3]

Score

[edit]Scoring is based on time taken to complete the test (e.g. 35 seconds yielding a score of 35) with lower scores being better. Different norms are available that allow comparison with age-matched groups.[7]

Time to complete

[edit]The entire test usually takes between 5 and 30 minutes. The average times to complete part A and B are 29 and 75 seconds, respectively. It is not necessary to continue the test if a patient cannot complete parts A and B within 5 minutes.

Population and usefulness

[edit]The population to be assessed includes adolescents, adults and the elderly.

The usefulness of this test in 1944 was to assess general intelligence, but in the 1950s researchers began to use it to assess cognitive dysfunction resulting from brain damage. It is now used as a diagnostic tool in clinical settings. It can also detect cognitive impairment associated with dementia.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Arnett, James A.; Seth S. Labovitz (1995). "Effect of physical layout in performance of the Trail Making Test". Psychological Assessment. 7 (2): 220–221. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.7.2.220. ProQuest 614331919.

- ^ Cahn, D. A.; et al. (1995). "Detection of dementia of the Alzheimer type in a population-based sample: Neuropsychological test performance". Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 800 (3): 252–260. doi:10.1017/s1355617700000242. PMID 9375219. S2CID 26793774.

- ^ a b c d e Tombaugh, T.N.T.N (2004). "Trail Making test A and B: Normative Data Stratified by Age and Education". Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 19 (2): 203–214. doi:10.1016/s0887-6177(03)00039-8. PMID 15010086. ProQuest 71715116.

- ^ R. M. Reitan, R. M. (1955). The relation of the trail making test to organic brain damage. Journal of Consulting Psychology

- ^ Reitan, R. M. (1958). "Validity of the Trail Making test as an indicator of organic brain damage". Perceptual and Motor Skills. 8 (3): 271–276. doi:10.2466/pms.1958.8.3.271. S2CID 144077004.

- ^ a b Bowie, C.R.C.R; P.D.P.D Harvey (2006). "Administration and interpretation of the trail making test". Nature Protocols. 1 (5): 2277–2281. doi:10.1038/nprot.2006.390. PMID 17406468. S2CID 32511403. ProQuest 68327018.

- ^ Lezak, Muriel Deutsch (2012). Neuropsychological assessment. Diane B. Howieson, Erin D. Bigler, Daniel Tranel (5 ed.). Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-539552-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

- Corrigan, J. D.; Hinkeldey, M. S. (1987). "Relationships between parts A and B of the Trail Making Test". J. Clin. Psychol. 43 (4): 402–409. doi:10.1002/1097-4679(198707)43:4<402::aid-jclp2270430411>3.0.co;2-e. PMID 3611374.

- Gaudino, E. A.; Geisler, M. W.; Squires, N. K. (1995). "Construct validity in the Trail Making Test: What makes Part B harder?". J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 17 (4): 529–535. doi:10.1080/01688639508405143. PMID 7593473.

Further reading

[edit]- Groth-Marnat, Gary (2009). Handbook of Psychological Assessment (Fifth ed.). Hoboken (NJ): Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-08358-1.

- Strauss, Esther; Sherman, Elizabeth M.; Spreen, Otfried (2006). A Compendium of Neuropsychological Tests: Administration, Norms, and Commentary. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-515957-8. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

External links

[edit]- PEBL Test Battery A free computer-based research-oriented implementation of the trail-making test is available as part of the PEBL Project

Trail Making Test

View on GrokipediaOverview

Description

The Trail Making Test (TMT) is a neuropsychological assessment that requires participants to connect a series of dots in a specific sequence on a worksheet, evaluating visual search, scanning, speed of processing, mental flexibility, and executive functioning.[1][8] This test serves as a measure of cognitive efficiency through tasks demanding sustained attention and task-switching between stimuli.[9] The TMT consists of two primary parts presented on separate sheets. In Part A, examinees draw lines to connect 25 circles labeled with numbers from 1 to 25 in ascending order. In Part B, they connect 25 circles alternating between numbers (1 to 13) and letters (A to L), following the sequence 1-A-2-B-3-C, and so forth.[1][8] The circles are scattered randomly across an 8.5 by 11-inch page to simulate real-world visual search demands without providing directional cues.[8][10] Designed as a quick, non-verbal tool, the TMT typically requires 5 to 10 minutes for administration, making it suitable for clinical settings where efficient screening of cognitive impairments is needed.[8][4]Purpose and Cognitive Domains

The Trail Making Test (TMT) serves primarily as a screening tool for detecting cognitive impairment in clinical and research settings, particularly in populations at risk for neurological conditions. It evaluates key aspects of brain function, including attention, processing speed, visual-motor coordination, and executive functions such as set-shifting. Developed as a brief, sensitive measure, the TMT is widely employed to identify deficits that may indicate underlying brain pathology, with its simplicity allowing integration into broader neuropsychological batteries.[11][12] In terms of cognitive domains, the TMT targets visual attention through the requirement to scan and locate stimuli amid distractors, psychomotor speed via the timed motor response of connecting targets, and cognitive flexibility in alternating between conceptual sets. Part A emphasizes basic visuomotor tracking and sustained attention, while Part B incorporates divided attention and working memory to maintain the alternating sequence (e.g., numbers to letters). These elements collectively probe fluid intelligence and inhibitory control, with performance influenced by age and education-related factors.[13][14][15] Clinically, the TMT's rationale lies in its differential demands: completion time for Part A reflects foundational processing speed and visual scanning efficiency, whereas Part B introduces executive demands that reveal set-shifting impairments when the B-A difference is elevated. This contrast helps isolate pure executive deficits from general slowing, aiding diagnosis in conditions like mild cognitive impairment where early executive changes are prominent. The test is particularly sensitive to frontal-subcortical circuit disruptions, as seen in traumatic brain injury and dementia, where prolonged times or errors signal impaired planning and flexibility.[15][14][16]History and Development

Origins

The Trail Making Test originated from the 1938 Divided Attention Test (also known as Partington's Pathways Test) developed by psychologists John E. Partington and Russell G. Leiter as a measure of divided attention through connecting pathways.[2][17] This test drew from earlier visual-motor and attention tasks and was incorporated into the U.S. Army Individual Test Battery (AITB) in 1944 during World War II to assess general mental ability and screen for cognitive impairments in military personnel, particularly recruits, in a non-verbal manner to ensure accessibility across diverse individuals.[18][19] First published in 1944 within the AITB manual, the test underwent early validation through its deployment in the U.S. Army for identifying neurological impairments, providing initial evidence of its utility in detecting brain damage via timed performance on sequential connections.[19] This wartime application established the TMT as a practical tool for rapid cognitive screening in high-stakes clinical settings.Standardization and Evolution

In the 1950s, Ralph M. Reitan refined and standardized the Trail Making Test (TMT) for clinical use within the Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Battery (HRNB), establishing normative data for individuals aged 15 to 79 to assess brain dysfunction in adults.[18] This integration emphasized the TMT's sensitivity to organic brain damage, with Reitan's manual providing guidelines for administration, scoring, and interpretation based on empirical validation against neurological criteria. Key evolutions in the 1990s involved updates by Otfried Spreen and Esther Strauss, who compiled and refined normative data in their seminal compendium, first published in 1991 (with subsequent editions in 1998 and 2006), extending applicability to broader demographic groups by incorporating adjustments for age, education, gender, and cultural factors to enhance interpretative accuracy.[20] Their work synthesized existing studies into a comprehensive framework, promoting the TMT's adoption in diverse neuropsychological assessments beyond the original HRNB context. The test was also incorporated into automated batteries like the Automated Neuropsychological Assessment Metrics (ANAM), where it or analogous tasks supported computerized evaluation of attention and executive functions in military and clinical settings. Normative expansions in the 2000s addressed gaps in pediatric and elderly populations, with the Comprehensive Trail Making Test (CTMT) by Cecil R. Reynolds providing stratified data for ages 9 to 89, enabling age-appropriate assessments in developmental and geriatric contexts. This development improved the TMT's utility for detecting cognitive impairments across the lifespan, filling post-1950s limitations in the original adult-focused norms. By the 2010s and into 2025, the TMT evolved toward digital integration, with platforms like the Vienna Test System's TMT-L offering automated administration, precise timing, and enhanced error analysis for improved reliability in research and clinics. Cross-cultural adaptations proliferated, including non-English versions such as the Color Trails Test, which substitutes colors for numerals to reduce literacy biases in diverse populations.Administration

Materials and Procedure

The Trail Making Test (TMT) requires minimal materials for administration, consisting of standardized worksheets printed on 8.5 x 11-inch paper, a pencil or pen, a stopwatch, and practice sheets for demonstration. Each worksheet features 25 circles: Part A contains numbered circles from 1 to 25 randomly distributed across the page, while Part B includes numbered circles from 1 to 13 interspersed with lettered circles from A to L. As a public-domain instrument, forms can be reproduced, but standardized versions are available from publishers like Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc., ensuring consistent layout and sizing for reliable testing.[21][22] Administration occurs individually in a quiet, distraction-free environment, such as a testing room with a flat table surface, to minimize external influences on performance. The examiner positions the practice sheet flat in front of the participant, provides a pencil, and delivers clear verbal instructions: for the general task, the participant is directed to connect the circles in sequential order as quickly as possible without lifting the pencil from the paper or going outside the circles. A demonstration using the sample sheet is provided, during which the examiner traces the path while verbalizing the sequence (e.g., "Now, number 1... number 2...") to model the process; the participant then practices under supervision, with the examiner offering immediate feedback if needed. Once the practice is complete, the formal test sheet is placed in the same orientation, and timing begins precisely when the participant starts drawing upon the command "Go," continuing until completion or a 5-minute (300-second) cutoff per part.[22][23] If the participant makes an error, such as connecting to the wrong circle or perseverating on a previous sequence, the examiner immediately intervenes by saying "Stop" to halt progress, redirects to the last correct connection, and resumes timing without pausing the stopwatch; this ensures the total time reflects the full effort, including corrections, while preventing uncorrected errors from invalidating the trial. After initiating the task, the participant is instructed not to speak or provide verbal commentary to maintain focus. The entire TMT, including both parts and demonstrations, typically takes 5 to 10 minutes to administer. Specific sequencing instructions differ between Parts A and B, as detailed in their respective sections.[22][23]Parts A and B

The Trail Making Test is divided into two distinct parts, A and B, each presented on a separate worksheet containing 25 circles distributed across an 8.5 by 11-inch sheet of paper.[8] Part A requires the participant to draw lines connecting circles numbered 1 through 25 in ascending sequential order as quickly and accurately as possible, using a pencil without lifting it from the paper. The numbers are positioned randomly to necessitate visual scanning across the page. This part emphasizes straightforward sequential linking of numerical targets.[1] Part B builds on this by having the participant connect 25 circles that alternate between numbers (1 through 13) and letters (A through L), in the order 1-A-2-B-3-C and so on up to 13-L, again as quickly and accurately as possible without lifting the pencil. The targets are similarly randomized, requiring shifts between identifying and linking numerical and alphabetic elements.[8] The primary difference lies in task structure: Part A follows a single, linear numerical progression, whereas Part B incorporates alternating sequences that demand set-shifting between two categories, leading to higher error rates and longer durations. Per standard protocols, Part B is typically discontinued after 5 minutes if the participant has not finished.[1][8]Scoring and Interpretation

Calculation of Scores

The primary scores for the Trail Making Test (TMT) are the completion times for Parts A and B, measured in seconds from the examiner's "go" signal until the participant draws a line connecting the final target (number 25 for Part A or the last number-letter pair for Part B).[8] These times reflect visuomotor speed and attention for Part A and additional set-shifting demands for Part B, with longer durations indicating poorer performance.[24] Part B is discontinued after 5 minutes (300 seconds) if not completed, with the elapsed time recorded as the score; Part A is typically completed within 90 seconds, but longer times are allowed and recorded as is.[8][23] Error scoring supplements the time-based primary metric but is secondary in quantitative analysis. Errors include connecting to an incorrect target (sequence breaks), repeating a previously connected target (perseverations), or other deviations such as off-trail lines, and are tallied separately for each part while the participant corrects them under examiner guidance without pausing the timer.[14] The time spent correcting errors is incorporated into the overall completion time, emphasizing efficiency over error count alone.[23] Qualitative observations, such as whether the participant lifts the pencil between connections (indicating scanning strategy) versus drawing continuous lines, may also be noted to inform behavioral insights, though these do not contribute to formal scores.[14] Derived metrics adjust raw times to better isolate cognitive components beyond basic motor speed. The B-A difference score subtracts the Part A completion time from the Part B completion time, providing a measure of executive dysfunction relatively independent of visual scanning and motor confounds: [8] This subtraction helps attribute performance decrements in Part B to cognitive flexibility rather than general processing speed.[24] Additionally, the B/A ratio divides the Part B time by the Part A time, offering a relative index of set-shifting efficiency that normalizes for individual differences in baseline speed.[8]Normative Data and Cutoffs

The Trail Making Test (TMT) relies on normative data to interpret performance, with standards adjusted for demographic factors such as age, education, and sometimes gender to account for their influence on completion times. Seminal normative datasets, such as those developed by Tombaugh (2004), provide stratified means and standard deviations for TMT-A and TMT-B based on a large sample of 911 healthy adults aged 18–89 years, showing that completion times increase significantly with advancing age and lower education levels. For instance, in young adults aged 20–39 years with 13–16 years of education, the mean TMT-A time is approximately 23 seconds (SD = 6.6), while TMT-B averages 51 seconds (SD = 19.3); in contrast, for those aged 70–89 years with similar education, means rise to 50 seconds (SD = 20.3) for TMT-A and 133 seconds (SD = 72.4) for TMT-B. Heaton et al. (2004) extended these with demographically adjusted norms from over 1,800 healthy individuals, incorporating regression-based corrections for age, education, and gender (with minimal gender effects observed), enabling the derivation of T-scores (mean = 50, SD = 10) that facilitate cross-test comparisons. Impairment cutoffs are typically defined using these T-scores, where scores 1–2 standard deviations below the mean (T < 40 to T < 30) indicate mild to significant deficits, particularly on TMT-B, which is more sensitive to executive dysfunction. For example, a TMT-B time exceeding 90 seconds often corresponds to a T-score below 40 in younger cohorts, signaling potential cognitive impairment, though thresholds vary by demographic adjustments to avoid overpathologizing slower but normal performances in older or less-educated individuals. These cutoffs emphasize conceptual benchmarks rather than rigid absolutes, as prolonged times (e.g., >75 seconds for TMT-A or >200 seconds for TMT-B in adults) may warrant further evaluation when adjusted for norms. Pediatric normative data differ markedly from adult standards, reflecting developmental improvements in visuomotor and executive skills, with shorter completion times overall. For children aged 9–14 years, Reitan's original child norms (updated in comprehensive batteries) report TMT-A means around 20–30 seconds and TMT-B around 40–60 seconds, decreasing with age within this range; more recent cross-cultural data, such as from a large Latin American Spanish-speaking sample of 3,337 children aged 6–17 years, confirm these patterns with education adjustments to reduce bias in low-resource settings (Ardila et al., 2017). Adjustments for low education levels across all ages, as highlighted in Heaton et al. (2004), are crucial to minimize cultural and socioeconomic confounds, ensuring equitable interpretation. Recent studies from the 2020s have expanded cross-cultural applicability, addressing limitations in predominantly Western norms. For example, demographically adjusted norms for a Scandinavian cohort aged 41–84 years (Espenes et al., 2020) align closely with Heaton's distributions but incorporate regional literacy effects, while data for native Spanish-speaking adults in the US-Mexico border region emphasize education corrections (Marquine et al., 2021). As of 2024, additional normative datasets have been published for populations including Taiwanese elderly and Korean adults, further enhancing cross-cultural utility.[25][26] These updates prioritize high-impact, diverse samples to enhance global clinical utility without altering core T-score frameworks.| Age Group | Education (Years) | TMT-A Mean (SD, seconds) | TMT-B Mean (SD, seconds) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20–39 | 13–16 | 23 (6.6) | 51 (19.3) | Tombaugh (2004)[27] |

| 70–89 | 13–16 | 50 (20.3) | 133 (72.4) | Tombaugh (2004)[27] |

| 9–12 | 3–6 | 28 (12) | 62 (28) | Ardila et al. (2017)[28] |

Clinical Applications

Neuropsychological Assessment

The Trail Making Test (TMT) plays a central role in neuropsychological assessments by integrating with other instruments to profile executive functions comprehensively. It is frequently administered alongside tests such as the Stroop Color and Word Test, which evaluates inhibitory control and selective attention, and the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST), which measures set-shifting and abstract reasoning, allowing clinicians to differentiate between various aspects of cognitive flexibility and attention.[29][30] This combination enhances the evaluation of prefrontal cortex functions, where TMT performance, particularly Part B, correlates with activation in frontoparietal networks during task-switching demands.[31] In diagnostic contexts, the TMT demonstrates utility in identifying cognitive impairments across neurological and psychiatric conditions. Elevated completion times on Part B are indicative of executive dysfunction in disorders such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), where adults show slower psychomotor integration compared to controls; schizophrenia, with comparable deficits to traumatic brain injury patients in set-shifting metrics; and post-stroke populations, reflecting vascular impacts on attention and processing speed.[32][33][8] The B-A difference score specifically aids in localizing frontal lobe involvement, as longer intervals are associated with prefrontal lesions, distinguishing them from posterior or diffuse impairments.[34][35] As a screening tool, the TMT serves as a rapid, sensitive indicator of cognitive decline in primary care settings, often taking under five minutes to administer and interpret. It detects early progression in mild cognitive impairment (MCI), with Part B sensitivities around 43-50% for identifying conversion to dementia, outperforming some standalone screeners in executive domain specificity.[36][12] The test is recommended in standard neuropsychological batteries, such as the Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Battery, for assessing attention and cognitive flexibility, aligning with guidelines from organizations like the National Academy of Neuropsychology that emphasize its inclusion in comprehensive evaluations over brief screens alone.[37][38] This positions the TMT as a foundational element in broader assessments of cognitive domains like flexibility, complementing detailed explorations elsewhere.[2]Specific Populations

In older adults, particularly those with dementia, elevated completion times on the Trail Making Test (TMT) Parts A and B serve as a prognostic indicator for Alzheimer's disease progression. Studies have shown that longer TMT-B times are associated with a higher risk of conversion from mild cognitive impairment (MCI) to Alzheimer's dementia, with predictive accuracies reaching approximately 65% when combined with other cognitive measures. For instance, research utilizing the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative dataset demonstrated that TMT-B scores at baseline significantly contributed to forecasting MCI-to-Alzheimer's progression over three years. Additionally, the Comprehensive Trail Making Test has been validated for MCI screening in elderly patients, where cutoff times exceeding 84 seconds on simpler trails yielded 75% sensitivity in distinguishing MCI from normal cognition.[39][40][40] Among children and adolescents, normative data for the TMT indicate shorter completion times compared to adults, reflecting developmental differences in visuomotor and executive skills. In populations with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), the test effectively assesses attention deficits, with Part B particularly sensitive to hyperactivity and set-shifting impairments; children with ADHD typically exhibit longer times and more errors on TMT-B than neurotypical peers, aiding in diagnostic differentiation with up to 80% accuracy in some batteries. Normative studies for preschoolers and school-aged children emphasize age-stratified benchmarks, such as mean TMT-A times under 30 seconds for ages 5-6, which highlight the test's utility in early identification of executive function challenges.[41][42][41] For individuals with neurological conditions like post-stroke or traumatic brain injury (TBI), the TMT requires motor adjustments to account for upper extremity impairments, such as using an oral version where participants verbalize connections instead of drawing lines. In post-stroke patients, prolonged TMT times correlate with executive dysfunction and reduced processing speed, informing rehabilitation planning. Similarly, in TBI cohorts, TMT performance at six months post-injury reveals persistent cognitive profiles, with errors on Part B linked to frontal lobe damage. In Parkinson's disease, TMT-B delays indicate executive and set-shifting deficits related to frontal-striatal dysfunction.[8][43][44][45][46][47] Cultural adaptations enhance applicability in non-Western groups; for example, Moroccan normative data adjust for education and age effects, while cross-cultural versions like the Color Trails Test minimize literacy biases in diverse linguistic contexts. Gender differences in TMT performance are minimal across populations, though education level significantly influences the B-A difference score, with higher education associated with smaller disparities between parts. Recent 2025 analyses underscore the TMT's role in evaluating driving fitness among seniors, where extended TMT-B times predict unsafe on-road performance, supporting clinical decisions on mobility.[48][49]Variants and Adaptations

Digital Versions

Digital versions of the Trail Making Test (TMT) have been developed as tablet- or software-based adaptations, utilizing touch-screen or mouse inputs to replace traditional paper-and-pencil methods. These implementations include iPad applications, such as the version adapted by Parker-O'Brien, which follows the standard TMT structure with Parts A and B, and Android-based apps like the TMT App for cognitive evaluation. Other examples encompass online platforms like CogniFit's digitized TMT, accessible via computers, smartphones, or tablets, where users click or tap numbered and lettered circles in sequence. These formats maintain the core task of connecting stimuli while capturing fine-grained data, such as pen strokes or touch trajectories, through electromagnetic tablets or digital interfaces. Key advantages of digital TMT versions include automated scoring and precise timing measurements, which standardize administration and eliminate manual stopwatch errors inherent in paper-based tests. They enable unlimited practice trials for repeated assessments and facilitate remote administration, particularly beneficial for telehealth applications following the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, as demonstrated by self-administered digital versions showing moderate to good reliability (ICC = 0.73–0.80 for Parts A and B). In elderly populations, these versions reduce motor confounds by isolating cognitive processes like processing speed and inhibitory control from gross motor demands, using component subscores derived from pauses, lifts, and velocity metrics, thereby providing more nuanced insights into executive function deficits. Recent developments highlight hybrid approaches combining paper and electronic elements, such as a 2023 study introducing an electromagnetic tablet-based TMT that records hand-drawn paths for automatic feature extraction (e.g., time, pressure, jerk). This hybrid achieved high classification accuracies for cognitive impairment (up to 0.929 for healthy vs. Alzheimer's disease) using random forest models. Validity studies confirm equivalence to manual versions, with high correlations reported, such as r = 0.89 for TMT-B in depressed individuals and r = 0.799 overall between digital and paper TMT-B. These adaptations preserve the test's sensitivity to attention and task-switching while enhancing accessibility and data richness for clinical and research settings.Modified Tests

The Comprehensive Trail Making Test (CTMT) extends the original Trail Making Test by incorporating five distinct visual search and sequencing trails (Trails 1 through 5), which progressively increase in complexity to better assess attention, concentration, and executive functioning while minimizing practice effects through alternate forms.[50] Developed by Cecil R. Reynolds, the CTMT provides standardized norms for individuals aged 9 to 75 years, enabling broader application across developmental and aging populations.[50] A 2023 validation study demonstrated its utility in identifying mild cognitive impairment (MCI) in older adults, with Trail 5 scores showing high sensitivity (AUC = 0.80) for distinguishing MCI from healthy controls, thus enhancing diagnostic accuracy in repeated assessments.[12] The Stepping Trail Making Test (S-TMT), introduced in 2020, modifies the traditional format by requiring participants to physically step on numbered and lettered mats arranged on the floor, integrating motor execution with cognitive sequencing to evaluate dual-task performance.[51] This adaptation assesses motor-cognitive interactions, particularly in populations with mobility challenges, and has demonstrated good reliability (test-retest ICC > 0.80) and construct validity in community-dwelling older adults.[52] Other modifications address accessibility barriers in diverse populations. The alphabet-supported Trail Making Test, validated in 2023, provides an auxiliary alphabet list to assist participants with dyslexia or limited alphabet automatization, thereby reducing false positives for executive dysfunction without altering the test's sensitivity to set-shifting (correlation with standard TMT-B: r = 0.92). Similarly, the Color Trails Test (CTT) replaces alphanumeric stimuli with colored circles (pink and yellow) to promote cultural neutrality, minimizing biases related to language or education while maintaining equivalence to the original test in measuring attention and processing speed (r = 0.78-0.85 across constructs).[54] These adaptations collectively improve the test's applicability in low-literacy or multicultural settings, filling gaps in the standard version's inclusivity. A 2024 adaptation, the Trail Making Test in Virtual Reality (TMT-VR), immerses participants in simulated environments to connect targets using VR controllers or hand tracking, enhancing ecological validity for assessing cognitive flexibility in real-world-like scenarios. Initial evaluations in young adults showed comparable performance across interaction modes, with potential applications for populations like those with ADHD.[55]Limitations

Confounds and Biases

The Trail Making Test (TMT) is susceptible to motor and visual confounds that can inflate completion times, particularly in Part A, which relies heavily on visuomotor coordination and scanning speed. Conditions such as arthritis or other motor impairments slow the physical act of connecting targets with a pencil, while poor vision hinders accurate target identification and line drawing.[13][56] To mitigate these, examiners may adjust scores for known motor limitations or opt for alternatives like the oral version of the TMT, which eliminates manual drawing demands.[57] Education and literacy levels introduce biases, especially in Part B, which presupposes familiarity with the alphabet for alternating number-letter sequencing. Lower education correlates with longer completion times due to reduced exposure to such tasks, potentially confounding executive function assessment. Using the B/A ratio helps partial out basic visuomotor and processing speed effects captured in Part A, isolating set-shifting demands more effectively.[58][59] Cultural factors further complicate interpretation, as the standard TMT assumes alphabetic and numeric conventions that may not align with non-Western or non-alphabetic societies. In such contexts, unfamiliarity with letters or sequential ordering can prolong times, unrelated to cognitive deficits; adaptations like the black-and-white or shape trail tests replace letters with neutral symbols to reduce these biases. Age-related slowing in TMT performance is often normative rather than pathological, particularly in culturally diverse groups where baseline expectations vary.[60][61] Practice effects diminish the test's utility in serial administrations, with repeated exposure leading to faster times that mask true cognitive changes. Recent studies highlight limitations of single-trial formats, showing variability across multiple administrations that underscores the need for alternate forms in longitudinal monitoring.[62][63]Reliability and Validity

The Trail Making Test (TMT) demonstrates generally strong psychometric properties, though with some variability across its parts. Test-retest reliability for Part A ranges from approximately 0.40 to 0.90 across studies, with lower values (e.g., around 0.50) often observed in healthy adults due to ceiling effects and low variability, and higher reliability (0.70-0.90) in clinical samples where greater variability enhances stability over short intervals (e.g., 1-4 weeks).[8] For Part B, reliability is moderate, often between 0.60 and 0.80, partly attributable to learning effects that can influence repeated administrations.[8] Internal consistency is moderate, with McDonald's omega values around 0.64 in dementia populations, indicating acceptable but not exceptional homogeneity within the test components.[64] Construct validity is supported by moderate correlations with other executive function measures, such as the Stroop Color-Word Test (r ≈ 0.35-0.40), underscoring TMT's sensitivity to inhibition and cognitive flexibility.[65] Criterion validity is evident in its ability to predict dementia outcomes; for example, studies report Part B sensitivity of 70-80% and specificity around 80% for distinguishing mild cognitive impairment (MCI) from healthy controls at optimized cutoffs.[66] Alternate forms, such as the Comprehensive Trail-Making Test (CTMT), improve reliability by reducing practice effects, yielding test-retest coefficients of 0.76-0.89 for Part A equivalents and 0.86-0.94 for Part B equivalents.[67] Recent research from 2023-2025 affirms the TMT's validity in digital adaptations and MCI contexts, addressing gaps in traditional psychometric evaluations. For instance, hybrid paper-electronic versions achieve 73% accuracy in classifying MCI versus controls, with stable follow-up performance.[36] Digital implementations, like the digitized TMT-B, exhibit high test-retest reliability (ICC = 0.87 for completion time) and internal consistency (α = 0.68), confirming equivalence to paper-based forms in detecting executive deficits in MCI.[68] These updates highlight the test's ongoing relevance despite confounds like practice effects.[8]References

- https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/[psychology](/page/Psychology)/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1227578/full