Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

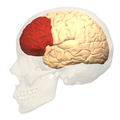

Prefrontal cortex

View on Wikipedia| Prefrontal cortex | |

|---|---|

Brodmann areas, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 24, 25, 32, 44, 45, 46, and 47 are all in the prefrontal cortex[1] | |

| Details | |

| Part of | Frontal lobe |

| Parts | Superior frontal gyrus Middle frontal gyrus Inferior frontal gyrus |

| Artery | Anterior cerebral Middle cerebral |

| Vein | Superior sagittal sinus |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | cortex praefrontalis |

| MeSH | D017397 |

| NeuroNames | 2429 |

| NeuroLex ID | nlx_anat_090801, ilx_0109209 |

| FMA | 224850 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

In mammalian brain anatomy, the prefrontal cortex (PFC) covers the front part of the frontal lobe of the brain. It is the association cortex in the frontal lobe.[2][3] This region is responsible for being able to process and change one's thinking in order to meet certain goals in a situation.[4] These processes of thinking can include the brain allowing one to focus, control how they behave, and make different decisions.[5]

The PFC contains the Brodmann areas BA8, BA9, BA10, BA11, BA12, BA13, BA14, BA24, BA25, BA32, BA44, BA45, BA46, and BA47.[1]

This brain region is involved in a wide range of higher-order cognitive functions, including speech formation (Broca's area), gaze (frontal eye fields), working memory (dorsolateral prefrontal cortex), and risk processing (e.g. ventromedial prefrontal cortex). The basic activity of this brain region is considered to be orchestration of thoughts and actions in accordance with internal goals.[6] Many authors have indicated an integral link between a person's will to live, personality, and the functions of the prefrontal cortex.[7]

This brain region has been implicated in executive functions, such as planning, decision making, working memory, personality expression, moderating social behavior and controlling certain aspects of speech and language.[8][9][10][11] Executive function relates to abilities to differentiate among conflicting thoughts, determine good and bad, better and best, same and different, future consequences of current activities, working toward a defined goal, prediction of outcomes, expectation based on actions, and social "control" (the ability to suppress urges that, if not suppressed, could lead to socially unacceptable outcomes).

The frontal cortex supports concrete rule learning, with more anterior regions supporting rule learning at higher levels of abstraction.[12]

Structure

[edit]Definition

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (March 2017) |

There are three possible ways to define the prefrontal cortex:[citation needed]

- as the granular frontal cortex

- as the projection zone of the medial dorsal nucleus of the thalamus

- as that part of the frontal cortex whose electrical stimulation does not evoke movements

Granular frontal cortex

[edit]The prefrontal cortex has been defined based on cytoarchitectonics by the presence of a cortical granular layer IV. It is not entirely clear who first used this criterion. Many of the early cytoarchitectonic researchers restricted the use of the term prefrontal to a much smaller region of cortex including the gyrus rectus and the gyrus rostralis (Campbell, 1905; G. E. Smith, 1907; Brodmann, 1909; von Economo and Koskinas, 1925). In 1935, however, Jacobsen used the term prefrontal to distinguish granular prefrontal areas from agranular motor and premotor areas.[13] In terms of Brodmann areas, the prefrontal cortex traditionally includes areas 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 24, 25, 32, 44, 45, 46, and 47,[1] however, not all of these areas are strictly granular – 44 is dysgranular, caudal 11 and orbital 47 are agranular.[14] The main problem with this definition is that it works well only in primates but not in nonprimates, as the latter lack a granular layer IV.[15] In a recent research study, scientists stimulated the amygdala area in monkeys, where they found that the auditory and prefrontal cortices got activated, which is similar to what happens in humans.[16]

Projection zone

[edit]To define the prefrontal cortex as the projection zone of the mediodorsal nucleus of the thalamus builds on the work of Rose and Woolsey,[17] who showed that this nucleus projects to anterior and ventral parts of the brain in nonprimates, however, Rose and Woolsey termed this projection zone "orbitofrontal." It seems to have been Akert, who, for the first time in 1964, explicitly suggested that this criterion could be used to define homologues of the prefrontal cortex in primates and nonprimates.[18] This allowed the establishment of homologies despite the lack of a granular frontal cortex in nonprimates.

The projection zone definition is still widely accepted today (e.g. Fuster[19]), although its usefulness has been questioned.[14][20] Modern tract tracing studies have shown that projections of the mediodorsal nucleus of the thalamus are not restricted to the granular frontal cortex in primates. As a result, it was suggested to define the prefrontal cortex as the region of cortex that has stronger reciprocal connections with the mediodorsal nucleus than with any other thalamic nucleus.[15] Uylings et al.[15] acknowledge, however, that even with the application of this criterion, it might be rather difficult to define the prefrontal cortex unequivocally.

Electrically silent area of frontal cortex

[edit]A third definition of the prefrontal cortex is the area of frontal cortex whose electrical stimulation does not lead to observable movements. For example, in 1890, David Ferrier[21] used the term in this sense. One complication with this definition is that the electrically "silent" frontal cortex includes both granular and non-granular areas.[14]

Subdivisions

[edit]This section needs attention from an expert in neuroscience. See the talk page for details. (May 2019) |

According to Striedter,[22] the PFC of humans can be delineated into two functionally, morphologically, and evolutionarily different regions: the ventromedial PFC (vmPFC) consisting of:

- the ventral prefrontal cortex (VPFC)

- the medial prefrontal cortex present in all mammals (MPFC)

and the lateral prefrontal cortex (LPFC), consisting of:

- the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC)

- the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (VLPFC) present only in primates.

The LPFC contains the Brodmann areas BA8, BA9, BA10, BA45, BA46, and BA47. Some researchers also include BA44. The vmPFC contains the Brodmann areas BA12, BA25, BA32, BA33, BA24, BA11, BA13, and BA14.

The table below shows different ways to subdivide parts of the human prefrontal cortex based upon Brodmann areas.[1]

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 46 | 45 | 47 | 44 | 12 | 25 | 32 | 33 | 24 | 11 | 13 | 14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lateral | ventromedial | |||||||||||||

| dorsolateral | ventrolateral | medial | ventral | |||||||||||

- The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex is composed of the BA8, BA9, BA10, and BA46.[1]

- The ventrolateral prefrontal cortex is composed of areas BA45, BA47, and BA44.[1]

- The medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) is composed of BA12, BA25, and anterior cingulate cortex: BA32, BA33, BA24.[1] Within that area is the dorsal nexus, which interconnects many parts of the brain.[23]

- The ventral prefrontal cortex is composed of areas BA11, BA13, and BA14.[1] (Also see the definition of the orbitofrontal cortex.)

- The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex contains BA8, including the frontal eye fields.[1]

- The ventrolateral prefrontal cortex contains BA45 which is part of Broca's area.[24] Some researchers also include BA44 the other part of Broca's area.

Interconnections

[edit]The prefrontal cortex is highly interconnected with much of the brain, including extensive connections with other cortical, subcortical and brain stem sites.[25] The dorsal prefrontal cortex is especially interconnected with brain regions involved with attention, cognition and action,[26] while the ventral prefrontal cortex interconnects with brain regions involved with emotion.[27] The prefrontal cortex also receives inputs from the brainstem arousal systems, and its function is particularly dependent on its neurochemical environment.[28] Thus, there is coordination between one's state of arousal and mental state.[29] The interplay between the prefrontal cortex and socioemotional system of the brain is relevant for adolescent development, as proposed by the Dual Systems Model.

The medial prefrontal cortex has been implicated in the generation of slow-wave sleep (SWS), and prefrontal atrophy has been linked to decreases in SWS.[30] Prefrontal atrophy occurs naturally as individuals age, and it has been demonstrated that older adults experience impairments in memory consolidation as their medial prefrontal cortices degrade.[30] In older adults, instead of being transferred and stored in the neocortex during SWS, memories start to remain in the hippocampus where they were encoded, as evidenced by increased hippocampal activation compared to younger adults during recall tasks, when subjects learned word associations, slept, and then were asked to recall the learned words.[30]

The ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (VLPFC) has been implicated in various aspects of speech production and language comprehension. The VLPFC is richly connected to various regions of the brain including the lateral and medial temporal lobe, the superior temporal cortex, the infertemporal cortex, the perirhinal cortex, and the parahippoccampal cortex.[31] These brain areas are implicated in memory retrieval and consolidation, language processing, and association of emotions. These connections allow the VLPFC to mediate explicit and implicit memory retrieval and integrate it with language stimulus to help plan coherent speech.[32] In other words, choosing the correct words and staying "on topic" during conversation come from the VLPFC.

Function

[edit]Executive function

[edit]The original studies of Fuster and of Goldman-Rakic emphasized the fundamental ability of the prefrontal cortex to represent information not currently in the environment, and the central role of this function in creating the "mental sketch pad". Goldman-Rakic spoke of how this representational knowledge was used to intelligently guide thought, action, and emotion, including the inhibition of inappropriate thoughts, distractions, actions, and feelings.[33] In this way, working memory can be seen as fundamental to attention and behavioral inhibition. Fuster speaks of how this prefrontal ability allows the integration of past and future, allowing both cross-temporal and cross-modal associations in the creation of goal-directed, perception-action cycles.[34] This ability to represent underlies all other higher executive functions. The prefrontal cortex is responsible for many executive functions, such as remembering information, cognitive flexibility, and inhibitory control.[35]

Shimamura proposed Dynamic Filtering Theory to describe the role of the prefrontal cortex in executive functions. The prefrontal cortex is presumed to act as a high-level gating or filtering mechanism that enhances goal-directed activations and inhibits irrelevant activations. This filtering mechanism enables executive control at various levels of processing, including selecting, maintaining, updating, and rerouting activations. It has also been used to explain emotional regulation.[36]

Miller and Cohen proposed an Integrative Theory of Prefrontal Cortex Function, that arises from the original work of Goldman-Rakic and Fuster. The two theorize that "cognitive control stems from the active maintenance of patterns of activity in the prefrontal cortex that represents goals and means to achieve them. They provide bias signals to other brain structures whose net effect is to guide the flow of activity along neural pathways that establish the proper mappings between inputs, internal states, and outputs needed to perform a given task".[37] In essence, the two theorize that the prefrontal cortex guides the inputs and connections, which allows for cognitive control of our actions.

The prefrontal cortex is of significant importance when top-down processing is needed. Top-down processing by definition is when behavior is guided by internal states or intentions. According to the two, "The PFC is critical in situations when the mappings between sensory inputs, thoughts, and actions either are weakly established relative to other existing ones or are rapidly changing".[37] An example of this can be portrayed in the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST). Subjects engaging in this task are instructed to sort cards according to the shape, color, or number of symbols appearing on them. The thought is that any given card can be associated with a number of actions and no single stimulus-response mapping will work. Human subjects with PFC damage are able to sort the card in the initial simple tasks, but unable to do so as the rules of classification change.

Miller and Cohen conclude that the implications of their theory can explain how much of a role the PFC has in guiding control of cognitive actions. In the researchers' own words, they claim that, "depending on their target of influence, representations in the PFC can function variously as attentional templates, rules, or goals by providing top-down bias signals to other parts of the brain that guide the flow of activity along the pathways needed to perform a task".[37]

Experimental data indicate a role for the prefrontal cortex in mediating normal sleep physiology, dreaming and sleep-deprivation phenomena.[38]

When analyzing and thinking about attributes of other individuals, the medial prefrontal cortex is activated, however, it is not activated when contemplating the characteristics of inanimate objects.[39]

Studies using fMRI have shown that the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), specifically the anterior medial prefrontal cortex (amPFC), may modulate mimicry behavior. Neuroscientists are suggesting that social priming influences activity and processing in the amPFC, and that this area of the prefrontal cortex modulates mimicry responses and behavior.[40]

As of recent, researchers have used neuroimaging techniques to find that along with the basal ganglia, the prefrontal cortex is involved with learning exemplars, which is part of the exemplar theory, one of the three main ways our mind categorizes things. The exemplar theory states that we categorize judgements by comparing it to a similar past experience within our stored memories.[41]

A 2014 meta-analysis by Professor Nicole P.Yuan from the University of Arizona found that larger prefrontal cortex volume and greater PFC cortical thickness were associated with better executive performance.[42]

Attention and memory

[edit]

A widely accepted theory regarding the function of the brain's prefrontal cortex is that it serves as a store of short-term memory. This idea was first formulated by Jacobsen, who reported in 1936 that damage to the primate prefrontal cortex caused short-term memory deficits.[44] Karl Pribram and colleagues (1952) identified the part of the prefrontal cortex responsible for this deficit as area 46, also known as the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC).[45] More recently, Goldman-Rakic and colleagues (1993) evoked short-term memory loss in localized regions of space by temporary inactivation of portions of the dlPFC.[46] Once the concept of working memory (see also Baddeley's model of working memory) was established in contemporary neuroscience by Alan Baddeley (1986), these neuropsychological findings contributed to the theory that the prefrontal cortex implements working memory and, in some extreme formulations, only working memory.[47] In the 1990s this theory developed a wide following, and it became the predominant theory of PF function, especially for nonhuman primates. The concept of working memory used by proponents of this theory focused mostly on the short-term maintenance of information, and rather less on the manipulation or monitoring of such information or on the use of that information for decisions. Consistent with the idea that the prefrontal cortex functions predominantly in maintenance memory, delay-period activity in the PF has often been interpreted as a memory trace. (The phrase "delay-period activity" applies to neuronal activity that follows the transient presentation of an instruction cue and persists until a subsequent "go" or "trigger" signal.)

To explore alternative interpretations of delay-period activity in the prefrontal cortex, Lebedev et al. (2004) investigated the discharge rates of single prefrontal neurons as monkeys attended to a stimulus marking one location while remembering a different, unmarked location.[43] Both locations served as potential targets of a saccadic eye movement. Although the task made intensive demands on short-term memory, the largest proportion of prefrontal neurons represented attended locations, not remembered ones. These findings showed that short-term memory functions cannot account for all, or even most, delay-period activity in the part of the prefrontal cortex explored. The authors suggested that prefrontal activity during the delay-period contributes more to the process of attentional selection (and selective attention) than to memory storage.[11][48]

Speech production and language

[edit]Various areas of the prefrontal cortex have been implicated in a multitude of critical functions regarding speech production, language comprehension, and response planning before speaking.[10] Cognitive neuroscience has shown that the left ventrolateral prefrontal cortex is vital in the processing of words and sentences.

The right prefrontal cortex has been found to be responsible for coordinating the retrieval of explicit memory for use in speech, whereas the deactivation of the left is responsible for mediating implicit memory retrieval to be used in verb generation.[10] Recollection of nouns (explicit memory) is impaired in some amnesic patients with damaged right prefrontal cortices, but verb generation remains intact because of its reliance on left prefrontal deactivation.[32]

Many researchers now include BA45 in the prefrontal cortex because together with BA44 it makes up an area of the frontal lobe called Broca's area.[24] Broca's Area is widely considered the output area of the language production pathway in the brain (as opposed to Wernicke's area in the medial temporal lobe, which is seen as the language input area). BA45 has been shown to be implicated for the retrieval of relevant semantic knowledge to be used in conversation/speech.[10] The right lateral prefrontal cortex (RLPFC) is implicated in the planning of complex behavior, and together with bilateral BA45, they act to maintain focus and coherence during speech production.[32] However, left BA45 has been shown to be activated significantly while maintaining speech coherence in young people. Older people have been shown to recruit the right BA45 more so than their younger counterparts.[32] This aligns with the evidence of decreased lateralization in other brain systems during aging.

In addition, this increase in BA45 and RLPFC activity in combination of BA47 in older patients has been shown to contribute to "off-topic utterances." The BA47 area in the prefrontal cortex is implicated in "stimulus-driven" retrieval of less-salient knowledge than is required to contribute to a conversation.[32] In other words, elevated activation of the BA47 together with altered activity in BA45 and the broader RLPFC has been shown to contribute to the inclusion of less relevant information and irrelevant tangential conversational speech patterns in older subjects.

Clinical significance

[edit]In the last few decades, brain imaging systems have been used to determine brain region volumes and nerve linkages. Several studies have indicated that reduced volume and interconnections of the frontal lobes with other brain regions is observed in patients diagnosed with mental disorders; those subjected to repeated stressors;[49] those who excessively consume sexually explicit materials;[50] suicides;[51] criminals; sociopaths; those affected by lead poisoning;[52] It is believed that at least some of the human abilities to feel guilt or remorse, and to interpret reality, are dependent on a well-functioning prefrontal cortex.[53] The advanced neurocircuitry and self-regulatory function of the human prefrontal cortex is also associated with the higher sentience and sapience of humans,[54] as the prefrontal cortex in humans occupies a far larger percentage of the brain than in any other animal. It is theorized that, as the brain has tripled in size over five million years of human evolution,[55] the prefrontal cortex has increased in size sixfold.[56]

A review on executive functions in healthy exercising individuals noted that the left and right halves of the prefrontal cortex, which is divided by the medial longitudinal fissure, appears to become more interconnected in response to consistent aerobic exercise.[57] Two reviews of structural neuroimaging research indicate that marked improvements in prefrontal and hippocampal gray matter volume occur in healthy adults that engage in medium intensity exercise for several months.[58][59]

Chronic intake of alcohol leads to persistent alterations in brain function including altered decision-making ability. The prefrontal cortex of chronic alcoholics has been shown to be vulnerable to oxidative DNA damage and neuronal cell death.[60]

History

[edit]Perhaps the seminal case in prefrontal cortex function is that of Phineas Gage, whose left frontal lobe was destroyed when a large iron rod was driven through his head in an 1848 accident. The standard presentation is that, although Gage retained normal memory, speech and motor skills, his personality changed radically: He became irritable, quick-tempered, and impatient—characteristics he did not previously display — so that friends described him as "no longer Gage"; and, whereas he had previously been a capable and efficient worker, afterward he was unable to complete.[61] However, careful analysis of primary evidence shows that descriptions of Gage's psychological changes are usually exaggerated when held against the description given by Gage's doctor, the most striking feature being that changes described years after Gage's death are far more dramatic than anything reported while he was alive.[62][63]

Subsequent studies on patients with prefrontal injuries have shown that the patients verbalized what the most appropriate social responses would be under certain circumstances. Yet, when actually performing, they instead pursued behavior aimed at immediate gratification, despite knowing the longer-term results would be self-defeating.

The interpretation of this data indicates that not only are skills of comparison and understanding of eventual outcomes harbored in the prefrontal cortex but the prefrontal cortex (when functioning correctly) controls the mental option to delay immediate gratification for a better or more rewarding longer-term gratification result. This ability to wait for a reward is one of the key pieces that define optimal executive function of the human brain.[citation needed]

There is much current research devoted to understanding the role of the prefrontal cortex in neurological disorders. Clinical trials have begun on certain drugs that have been shown to improve prefrontal cortex function, including guanfacine, which acts through the alpha-2A adrenergic receptor. A downstream target of this drug, the HCN channel, is one of the most recent areas of exploration in prefrontal cortex pharmacology.[64]

Etymology

[edit]The term "prefrontal" as describing a part of the brain appears to have been introduced by Richard Owen in 1868.[13] For him, the prefrontal area was restricted to the anterior-most part of the frontal lobe (approximately corresponding to the frontal pole). It has been hypothesized that his choice of the term was based on the prefrontal bone present in most amphibians and reptiles.[13]

Additional images

[edit]-

Animation, prefrontal cortex of left cerebral hemisphere (shown in red)

-

Front view

-

Lateral view

-

Medial perspective

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Murray E, Wise S, Grahatle K (2016). "Chapter 1: The History of Memory Systems". The Evolution of Memory Systems: Ancestors, Anatomy, and Adaptations (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 22–24. ISBN 978-0-19-150995-7. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- ^ Fuster, Joaquín M. (2019). "The prefrontal cortex in the neurology clinic". The Frontal Lobes. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Vol. 163. pp. 3–15. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-804281-6.00001-X. ISBN 978-0-12-804281-6. PMID 31590737.

- ^ Harms, Madeline B.; Pollak, Seth D. (2024). "Emotion regulation". Encyclopedia of Adolescence. pp. 110–124. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-96023-6.00036-1. ISBN 978-0-323-95820-2.

The prefrontal cortex is the anterior section of the brain's frontal lobes. Central to the top-down control of attention, inhibition, emotion, complex learning, and theory-of-mind processing, the prefrontal cortex is a heterogeneous brain circuit composed of many important subdivisions (Duncan, 2001).

- ^ Widge, A. S.; Zorowitz, S.; Basu, I.; Paulk, A. C.; Cash, S. S.; Eskandar, E. N.; Deckersbach, T.; Miller, E. K.; Dougherty, D. D. (2019-04-04). "Deep brain stimulation of the internal capsule enhances human cognitive control and prefrontal cortex function". Nature Communications. 10 (1): 1536. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-09557-4. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 6449385. PMID 30948727.

- ^ Widge, A. S.; Zorowitz, S.; Basu, I.; Paulk, A. C.; Cash, S. S.; Eskandar, E. N.; Deckersbach, T.; Miller, E. K.; Dougherty, D. D. (2019-04-04). "Deep brain stimulation of the internal capsule enhances human cognitive control and prefrontal cortex function". Nature Communications. 10 (1): 1536. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-09557-4. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 6449385. PMID 30948727.

- ^ Miller EK, Freedman DJ, Wallis JD (August 2002). "The prefrontal cortex: categories, concepts and cognition". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 357 (1424): 1123–1136. doi:10.1098/rstb.2002.1099. PMC 1693009. PMID 12217179.

- ^ DeYoung CG, Hirsh JB, Shane MS, Papademetris X, Rajeevan N, Gray JR (June 2010). "Testing predictions from personality neuroscience. Brain structure and the big five". Psychological Science. 21 (6): 820–828. doi:10.1177/0956797610370159. PMC 3049165. PMID 20435951.

- ^ João, Rafael Batista; Filgueiras, Raquel Mattos (2018-10-03), Starcevic, Ana; Filipovic, Branislav (eds.), "Frontal Lobe: Functional Neuroanatomy of Its Circuitry and Related Disconnection Syndromes", Prefrontal Cortex, InTech, doi:10.5772/intechopen.79571, ISBN 978-1-78923-903-4, retrieved 2023-06-24

- ^ Yang Y, Raine A (November 2009). "Prefrontal structural and functional brain imaging findings in antisocial, violent, and psychopathic individuals: a meta-analysis". Psychiatry Research. 174 (2): 81–88. doi:10.1016/j.pscychresns.2009.03.012. PMC 2784035. PMID 19833485.

- ^ a b c d Gabrieli JD, Poldrack RA, Desmond JE (February 1998). "The role of left prefrontal cortex in language and memory". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 95 (3): 906–913. Bibcode:1998PNAS...95..906G. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.3.906. PMC 33815. PMID 9448258.

- ^ a b Baldauf D, Desimone R (April 2014). "Neural mechanisms of object-based attention". Science. 344 (6182): 424–427. Bibcode:2014Sci...344..424B. doi:10.1126/science.1247003. PMID 24763592.

- ^ Badre D, Kayser AS, D'Esposito M (April 2010). "Frontal cortex and the discovery of abstract action rules". Neuron. 66 (2): 315–326. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2010.03.025. PMC 2990347. PMID 20435006.

- ^ a b c Finger S (1994). Origins of neuroscience: a history of explorations into brain function. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514694-3.[page needed]

- ^ a b c Preuss TM (1995). "Do rats have prefrontal cortex? The rose-woolsey-akert program reconsidered". Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 7 (1): 1–24. doi:10.1162/jocn.1995.7.1.1. PMID 23961750.

- ^ a b c Uylings HB, Groenewegen HJ, Kolb B (November 2003). "Do rats have a prefrontal cortex?". Behavioural Brain Research. 146 (1–2): 3–17. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2003.09.028. PMID 14643455.

- ^ Li, Qianbing; Ping, An; Feng, Yuqi; Xu, Bin; Zhang, Baorong; Roe, Anna Wang; Gao, Lixia; Li, Xinjian (2025-09-01). "Mesoscale functional connectivity of amygdala to the auditory and prefrontal cortex of macaque monkeys revealed by INS-fMRI". NeuroImage. 318 121406. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2025.121406. ISSN 1053-8119.

- ^ Rose JE, Woolsey CN (1948). "The orbitofrontal cortex and its connections with the mediodorsal nucleus in rabbit, sheep and cat". Research Publications – Association for Research in Nervous and Mental Disease. 27: 210–232. PMID 18106857.

- ^ Preuss TM, Goldman-Rakic PS (August 1991). "Myelo- and cytoarchitecture of the granular frontal cortex and surrounding regions in the strepsirhine primate Galago and the anthropoid primate Macaca". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 310 (4): 429–474. doi:10.1002/cne.903100402. PMID 1939732.

- ^ Fuster JM (2008). The Prefrontal Cortex (4th ed.). Boston: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-373644-4.[page needed]

- ^ Markowitsch HJ, Pritzel M (1979). "The prefrontal cortex: Projection area of the thalamic mediodorsal nucleus?". Physiological Psychology. 7 (1): 1–6. doi:10.3758/bf03326611.

- ^ Ferrier D (June 1890). "The Croonian Lectures on Cerebral Localisation". British Medical Journal. 1 (1537): 1349–1355. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.1537.1349. PMC 2207859. PMID 20753055.

- ^ Striedter GF (2005). Principles of brain evolution. Sinauer Associates. ISBN 978-0-87893-820-9.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Sheline, Yvette; Yan, Shizi (2010). "Resting-state functional MRI in depression unmasks increased connectivity between networks via the dorsal nexus". PNAS. 107 (24): 11020–11025. Bibcode:2010PNAS..10711020S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1000446107. PMC 2890754. PMID 20534464.

- ^ a b "Broca area | anatomy". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-12-12.

- ^ Alvarez JA, Emory E (March 2006). "Executive function and the frontal lobes: a meta-analytic review". Neuropsychology Review. 16 (1): 17–42. doi:10.1007/s11065-006-9002-x. PMID 16794878.

- ^ Goldman-Rakic PS (1988). "Topography of cognition: parallel distributed networks in primate association cortex". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 11: 137–156. doi:10.1146/annurev.ne.11.030188.001033. PMID 3284439.

- ^ Price JL (June 1999). "Prefrontal cortical networks related to visceral function and mood". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 877 (1): 383–396. Bibcode:1999NYASA.877..383P. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb09278.x. PMID 10415660.

- ^ Robbins TW, Arnsten AF (2009). "The neuropsychopharmacology of fronto-executive function: monoaminergic modulation". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 32: 267–287. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135535. PMC 2863127. PMID 19555290.

- ^ Arnsten AF, Paspalas CD, Gamo NJ, Yang Y, Wang M (August 2010). "Dynamic Network Connectivity: A new form of neuroplasticity". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 14 (8): 365–375. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2010.05.003. PMC 2914830. PMID 20554470.

- ^ a b c Mander BA, Rao V, Lu B, Saletin JM, Lindquist JR, Ancoli-Israel S, et al. (March 2013). "Prefrontal atrophy, disrupted NREM slow waves and impaired hippocampal-dependent memory in aging". Nature Neuroscience. 16 (3): 357–364. doi:10.1038/nn.3324. PMC 4286370. PMID 23354332.

- ^ Kuhl BA, Wagner AD (2009-01-01). "Strategic Control of Memory". In Squire LR (ed.). Encyclopedia of Neuroscience. Academic Press. pp. 437–444. doi:10.1016/b978-008045046-9.00424-1. ISBN 978-0-08-045046-9.

- ^ a b c d e Hoffman P (January 2019). "Reductions in prefrontal activation predict off-topic utterances during speech production". Nature Communications. 10 (1) 515. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10..515H. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-08519-0. PMC 6355898. PMID 30705284.

- ^ Goldman-Rakic PS (October 1996). "The prefrontal landscape: implications of functional architecture for understanding human mentation and the central executive". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 351 (1346): 1445–1453. doi:10.1098/rstb.1996.0129. JSTOR 3069191. PMID 8941956.

- ^ Fuster JM, Bodner M, Kroger JK (May 2000). "Cross-modal and cross-temporal association in neurons of frontal cortex". Nature. 405 (6784): 347–351. Bibcode:2000Natur.405..347F. doi:10.1038/35012613. PMID 10830963.

- ^ Eng, Cassondra M.; Vargas, Roberto J.; Fung, Howard L.; Niemi, Selena R.; Pocsai, Melissa; Fisher, Anna V.; Thiessen, Erik D. (2025-08-01). "Prefrontal cortex intrinsic functional connectivity and executive function in early childhood and early adulthood using fNIRS". Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience. 74 101570. doi:10.1016/j.dcn.2025.101570. ISSN 1878-9293. PMC 12162044. PMID 40451067.

- ^ Shimamura AP (2000). "The role of the prefrontal cortex in dynamic filtering". Psychobiology. 28 (2): 207–218. doi:10.3758/BF03331979.

- ^ a b c Miller EK, Cohen JD (2001). "An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 24: 167–202. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.167. PMID 11283309.

- ^ Muzur A, Pace-Schott EF, Hobson JA (November 2002). "The prefrontal cortex in sleep". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 6 (11): 475–481. doi:10.1016/S1364-6613(02)01992-7. PMID 12457899.

- ^ Mitchell JP, Heatherton TF, Macrae CN (November 2002). "Distinct neural systems subserve person and object knowledge". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (23): 15238–15243. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9915238M. doi:10.1073/pnas.232395699. PMC 137574. PMID 12417766.

- ^ Wang Y, Hamilton AF (April 2015). "Anterior medial prefrontal cortex implements social priming of mimicry". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 10 (4): 486–493. doi:10.1093/scan/nsu076. PMC 4381231. PMID 25009194.

- ^ Schacter, Daniel L., Daniel Todd Gilbert, and Daniel M. Wegner. Psychology. 2nd ed, pages 364–366 New York, NY: Worth Publishers, 2011. Print.

- ^ Yuan P, Raz N (May 2014). "Prefrontal cortex and executive functions in healthy adults: a meta-analysis of structural neuroimaging studies". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 42: 180–192. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.02.005. PMC 4011981. PMID 24568942.

- ^ a b Lebedev MA, Messinger A, Kralik JD, Wise SP (November 2004). "Representation of attended versus remembered locations in prefrontal cortex". PLOS Biology. 2 (11) e365. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020365. PMC 524249. PMID 15510225.

- ^ Jacobsen C.F. (1936) Studies of cerebral function in primates. I. The functions of the frontal associations areas in monkeys. Comp Psychol Monogr 13: 3–60.

- ^ Pribram KH, Mishkin M, Rosvold HE, Kaplan SJ (December 1952). "Effects on delayed-response performance of lesions of dorsolateral and ventromedial frontal cortex of baboons". Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology. 45 (6): 565–575. doi:10.1037/h0061240. PMID 13000029.

- ^ Funahashi S, Bruce CJ, Goldman-Rakic PS (April 1993). "Dorsolateral prefrontal lesions and oculomotor delayed-response performance: evidence for mnemonic "scotomas"". The Journal of Neuroscience. 13 (4): 1479–1497. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-04-01479.1993. PMC 6576716. PMID 8463830.

- ^ Baddeley A. (1986) Working memory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p.289

- ^ Bedini M, Baldauf D (August 2021). "Structure, function and connectivity fingerprints of the frontal eye field versus the inferior frontal junction: A comprehensive comparison". The European Journal of Neuroscience. 54 (4): 5462–5506. doi:10.1111/ejn.15393. PMC 9291791. PMID 34273134.

- ^ Liston C, Miller MM, Goldwater DS, Radley JJ, Rocher AB, Hof PR, et al. (July 2006). "Stress-induced alterations in prefrontal cortical dendritic morphology predict selective impairments in perceptual attentional set-shifting". The Journal of Neuroscience. 26 (30): 7870–7874. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1184-06.2006. PMC 6674229. PMID 16870732.

- ^ "Viewers of pornography have a smaller reward system". MAX-PLANCK-GESELLSCHAFT. 2 June 2014. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- ^ Rajkowska G (December 1997). "Morphometric methods for studying the prefrontal cortex in suicide victims and psychiatric patients". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 836 (1): 253–268. Bibcode:1997NYASA.836..253R. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb52364.x. PMID 9616803.

- ^ Cecil KM, Brubaker CJ, Adler CM, Dietrich KN, Altaye M, Egelhoff JC, et al. (May 2008). Balmes J (ed.). "Decreased brain volume in adults with childhood lead exposure". PLOS Medicine. 5 (5) e112. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050112. PMC 2689675. PMID 18507499.

- ^ Anderson SW, Bechara A, Damasio H, Tranel D, Damasio AR (November 1999). "Impairment of social and moral behavior related to early damage in human prefrontal cortex". Nature Neuroscience. 2 (11): 1032–1037. doi:10.1038/14833. PMID 10526345.

- ^ Fariba K, Gokarakonda SB (2021). "Impulse Control Disorders". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 32965950. Retrieved 2021-05-04.

- ^ Schoenemann PT, Budinger TF, Sarich VM, Wang WS (April 2000). "Brain size does not predict general cognitive ability within families". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (9): 4932–4937. Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.4932S. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.9.4932. PMC 18335. PMID 10781101.

- ^ Cascio T. "House & Psychology, Episode 14". Psychology Today. Archived from the original on 2013-04-08. Retrieved 2011-11-15.

- ^ Guiney H, Machado L (February 2013). "Benefits of regular aerobic exercise for executive functioning in healthy populations". Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 20 (1): 73–86. doi:10.3758/s13423-012-0345-4. PMID 23229442.

- ^ Erickson KI, Leckie RL, Weinstein AM (September 2014). "Physical activity, fitness, and gray matter volume". Neurobiology of Aging. 35 (Suppl 2): S20 – S28. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.03.034. PMC 4094356. PMID 24952993.

- ^ Valkanova V, Eguia Rodriguez R, Ebmeier KP (June 2014). "Mind over matter--what do we know about neuroplasticity in adults?". International Psychogeriatrics. 26 (6): 891–909. doi:10.1017/S1041610213002482. PMID 24382194.

- ^ Fowler AK, Thompson J, Chen L, Dagda M, Dertien J, Dossou KS, et al. (2014). "Differential sensitivity of prefrontal cortex and hippocampus to alcohol-induced toxicity". PLOS ONE. 9 (9) e106945. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j6945F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0106945. PMC 4154772. PMID 25188266.

- ^ Antonio Damasio, Descartes' Error. Penguin Putman Pub., 1994[page needed]

- ^ Malcolm Macmillan, An Odd Kind of Fame: Stories of Phineas Gage (MIT Press, 2000), pp.116–119, 307–333, esp. pp.11,333.

- ^ Macmillan M (2008). "Phineas Gage – Unravelling the myth". The Psychologist. 21 (9). British Psychological Society: 828–831. Archived from the original on 2010-09-03. Retrieved 2014-06-21.

- ^ Wang M, Ramos BP, Paspalas CD, Shu Y, Simen A, Duque A, et al. (April 2007). "Alpha2A-adrenoceptors strengthen working memory networks by inhibiting cAMP-HCN channel signaling in prefrontal cortex". Cell. 129 (2): 397–410. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.015. PMID 17448997.

External links

[edit]Prefrontal cortex

View on GrokipediaAnatomy

Location and cytoarchitecture

The prefrontal cortex constitutes the anterior portion of the frontal lobes in each cerebral hemisphere, occupying the region rostral to the primary motor and premotor cortices. The entire frontal lobe, including the prefrontal cortex, is bounded posteriorly by the central sulcus, which separates it from the parietal lobe, and inferiorly by the lateral cerebral fissure (Sylvian fissure), which demarcates it from the temporal lobe. The prefrontal cortex's posterior boundary is specifically the premotor cortex, located anterior to the primary motor cortex (precentral gyrus). Laterally and superiorly, its extent reaches the frontal pole and the superior margin of the hemisphere, encompassing approximately 10-12% of the total cortical surface in humans.[5] Key sulci and gyri define its surface anatomy on the lateral, medial, and orbital surfaces. The superior frontal sulcus and inferior frontal sulcus run parallel across the lateral surface, dividing the prefrontal cortex into the superior frontal gyrus (dorsomedial), middle frontal gyrus (dorsolateral), and inferior frontal gyrus (ventrolateral). On the medial surface, the cingulate sulcus partially bounds the medial prefrontal regions, while the orbital surface features the olfactory sulcus and transverse orbital sulcus, separating the medial and lateral orbital gyri. These landmarks provide consistent boundaries for identifying prefrontal territories in neuroimaging and histological studies.[6][7] Cytoarchitectonically, the prefrontal cortex is classified primarily based on the work of Korbinian Brodmann, who delineated it into several distinct areas using cellular organization and lamination patterns: areas 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 24, 25, 32, 44, 45, 46, and 47. These areas exhibit a gradient in cortical granularity, reflecting variations in the development of layer IV (the internal granular layer). The frontopolar prefrontal cortex (Brodmann area 10) and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (areas 9 and 46) are characteristically granular, featuring a well-developed, densely packed layer IV rich in granule cells, which supports higher-order associative processing. In contrast, the orbitofrontal cortex (areas 11, 12, 13, and 14) is predominantly agranular or dysgranular, with a reduced or absent layer IV and larger pyramidal cells in layers V and VI, indicative of its transitional role between isocortex and allocortex. Some regions, such as area 44, show dysgranular features with a thin, discontinuous layer IV.[8][9][10] Historically, the prefrontal cortex was characterized by early neurophysiologists as comprising "electrically silent" zones—regions unresponsive to direct electrical stimulation in awake humans, distinguishing them from motor areas—and as projection zones receiving inputs from thalamic nuclei like the mediodorsal nucleus. These descriptors, originating from studies in the early 20th century, have been integrated into contemporary cytoarchitectonic frameworks, where they align with the granular prefrontal regions' lack of overt motor output and their dense reciprocal connections. Modern probabilistic atlases refine these maps using quantitative metrics of cell density, column spacing, and laminar thickness to account for interindividual variability.[11][12]Subregions

The prefrontal cortex is divided into several major subregions based on cytoarchitectonic and functional criteria, each corresponding to specific Brodmann areas. These include the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC, Brodmann areas 9 and 46), ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (VLPFC, areas 44, 45, and 47), orbitofrontal cortex (OFC, areas 11, 12, 13, and 14), and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC, including the anterior cingulate cortex in areas 24 and 32).[13] These divisions reflect evolutionary expansions, particularly in primates. The DLPFC, characterized by its granular cytoarchitecture with a prominent layer IV, is primarily involved in working memory, planning, and executive control.[14] Functional asymmetries exist here, with the left DLPFC specializing in verbal working memory tasks and the right in spatial processing.[13] The VLPFC supports response inhibition, object categorization, and language processing. It exhibits hemispheric differences, with the left VLPFC dominant in verbal and linguistic tasks and the right posterior portion (area 44) crucial for inhibitory control.[13][14] The OFC, encompassing both granular and dysgranular zones, plays a key role in reward valuation, decision-making, and emotional regulation. Lesions here impair judgment and social adaptation. The right OFC shows greater involvement in reward processing.[14][1][13] The mPFC, including the anterior cingulate, oversees emotion regulation, social cognition, and conflict monitoring. It often features less granular, proisocortical organization. Asymmetries include left mPFC associations with positive emotions and cognitive empathy, versus right-linked negative affect and affective empathy.[1][15][13]Connectivity

The prefrontal cortex (PFC) maintains extensive afferent and efferent connections with subcortical and cortical structures, enabling its role as an integrative hub. Afferent inputs to the PFC primarily arise from the mediodorsal nucleus of the thalamus, which provides reciprocal thalamocortical projections that relay sensory and associative information, with fibers traversing the anterior limb of the internal capsule (ALIC).[16] Efferent projections from the PFC target the basal ganglia, particularly the caudate nucleus, via the Muratoff bundle and ALIC, forming part of the corticostriatal pathways; dorsal PFC regions project dorsally around the striatum, while ventral areas project ventrally.[16] The PFC also projects to premotor and motor cortices, indirectly influencing motor control through its connections to premotor areas, which facilitate the selection of goals and suppression of actions. Unlike primary motor areas, the prefrontal cortex lacks somatotopic organization and does not have direct pyramidal tract output for primary musculature control.[17][18] The PFC also connects bidirectionally with the limbic system, including dense projections to the amygdala and hippocampus; for instance, the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) sends efferents to the amygdala, and the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) links to both the amygdala and hippocampus.[16] Additionally, the PFC receives afferents from sensory cortices, such as visual and auditory areas, facilitating multimodal integration.[19] Major white matter tracts underpin these connections, with the uncinate fasciculus (UF) serving as a key pathway linking the ventral PFC, including the OFC, to the temporal lobe and limbic structures like the amygdala.[16] The superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF), comprising subdivisions I, II, and III, connects the dorsolateral PFC (DLPFC) to parietal and temporal cortices, supporting frontoparietal network integration.[16] These tracts exhibit topographic organization, with human diffusion MRI confirming their trajectories observed in non-human primate tract-tracing studies.[16] Reciprocal loops further characterize PFC connectivity, including frontostriatal circuits that link the PFC to the striatum and basal ganglia via the caudate, enabling cognitive processing through closed-loop pathways involving the thalamus.[20] Frontolimbic circuits form bidirectional connections between the medial PFC and limbic regions such as the amygdala and hippocampus, with projections via the UF and cingulum bundle supporting emotional integration. White matter microstructure in the PFC, assessed via diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), reveals progressive changes that enhance connectivity efficiency, particularly through myelination. Systematic reviews of DTI studies indicate increased fractional anisotropy (FA) and decreased mean diffusivity (MD) in frontal white matter tracts from childhood to adulthood, reflecting heightened myelination, fiber organization, and integrity. In coherent fiber bundles like the SLF, myelin content strongly correlates with FA, facilitating faster axonal conduction and efficient signal transmission across PFC networks.[21]Functions

Executive functions

Executive functions refer to a set of higher-order cognitive processes that enable goal-directed behavior, including planning, decision-making (encompassing evaluation of risks), inhibitory control (which supports self-control and control of impulses), cognitive flexibility, and abstract thinking.[22][1] These processes allow individuals to coordinate thoughts and actions in novel situations, resist habitual responses, and adapt to changing demands.[2] The prefrontal cortex, particularly its dorsolateral region, plays a central role in orchestrating these functions through top-down control mechanisms.[23] This includes indirect influence on motor control, where the prefrontal cortex connects to premotor areas to facilitate goal selection and action suppression, without direct pyramidal tract outputs for primary musculature control or somatotopic organization.[24][17] Key theoretical models have shaped understanding of executive functions within the prefrontal cortex. Baddeley's working memory model posits a central executive as the supervisory component that manages attention, inhibits irrelevant information, and coordinates subordinate systems like the phonological loop and visuospatial sketchpad, with strong associations to prefrontal activity.[23] Complementing this, Miyake's unity/diversity framework identifies three core executive processes—updating (monitoring and revising working memory), shifting (flexible switching between tasks), and inhibition (suppressing prepotent responses)—which exhibit both common variance (unity) and distinct components (diversity), underpinned by prefrontal networks.[25][26] Neuroimaging studies demonstrate dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) activation during tasks assessing executive functions. In the Stroop task, which requires inhibitory control to resolve color-word conflicts, fMRI reveals heightened DLPFC engagement, particularly in the left hemisphere, for conflict monitoring and resolution.[27] Similarly, the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, probing cognitive flexibility and set-shifting, elicits DLPFC activation as participants detect rule changes and adapt strategies, with meta-analyses confirming consistent prefrontal involvement across studies.[28] Dopamine neurotransmission modulates executive functions via D1 and D2 receptors in prefrontal circuits. D1 receptors facilitate working memory and persistent neural firing for goal maintenance, while D2 receptors support flexibility and gating of irrelevant information, with optimal dopamine levels following an inverted-U curve for performance.[2][29] These receptors interact with prefrontal projections to the basal ganglia, enabling coordinated cognitive control.[2]Social and emotional processing

The prefrontal cortex, particularly its medial (mPFC) and orbitofrontal (OFC) subregions, plays a pivotal role in social cognition by enabling the attribution of mental states to others, a process known as theory of mind (ToM). Neuroimaging reviews indicate that the mPFC, including the anterior paracingulate cortex, is consistently activated during ToM tasks, facilitating the inference of others' beliefs, intentions, and emotions beyond mere self-referential processing.[30] This region integrates abstract social information, distinguishing ToM from basic perceptual judgments, as evidenced by greater mPFC engagement when evaluating psychological states compared to physical attributes. Empathy, encompassing both cognitive and affective components, also relies on prefrontal networks, with the mPFC supporting perspective-taking and the OFC modulating emotional resonance to others' experiences. Studies show that ventral portions of the mPFC are specifically implicated in emotional empathy, allowing individuals to vicariously share affective states while the OFC evaluates the reward value of empathetic responses.[31] Neurobiological models highlight how these areas form a distributed network that simulates others' mental states, essential for prosocial interactions.[32] In moral reasoning, the mPFC and OFC contribute to evaluating ethical dilemmas by weighing emotional salience against normative principles. The ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), overlapping with medial OFC, integrates affective inputs to guide judgments of harm and fairness, as lesions here lead to utilitarian biases favoring outcomes over intentions.[33] Functional anatomy research further links vmPFC/OFC activation to the anticipated moral value of decisions, distinguishing personal from impersonal moral contexts.[34] Emotional regulation within social contexts involves prefrontal mechanisms that modulate limbic responses, such as the vmPFC's inhibitory influence on the amygdala during reappraisal and suppression strategies, thereby enabling self-control in emotional responses. Reappraisal, which reframes emotional stimuli, recruits early prefrontal activation to reduce amygdala activity and negative affect, while suppression engages dorsolateral prefrontal regions to inhibit expressive behaviors.[35][36] Meta-analyses confirm that vmPFC-amygdala inverse coupling during regulation predicts effective downregulation of emotional intensity, particularly in social scenarios requiring composure.[37][38] Social decision-making highlights the OFC's role in valuing fairness, as seen in ultimatum game paradigms where unfair offers elicit prefrontal signals of inequity. Meta-analyses of neuroimaging data reveal that the lateral OFC processes the subjective value of social exchanges, integrating fairness norms with personal gain to influence acceptance or rejection decisions.[39] This valuation mechanism underscores how prefrontal circuits balance self-interest with cooperative norms in interpersonal interactions.[40] Sex differences in prefrontal emotional processing show that women exhibit greater right PFC involvement, particularly during reactivity to negative social cues. Meta-analyses of neuroimaging studies indicate enhanced right prefrontal activation in women for emotional stimuli, linked to heightened empathy and regulatory demands in social contexts.[41] This asymmetry may reflect adaptive differences in processing interpersonal emotions, with women showing more robust right-lateralized responses during reappraisal tasks compared to men.[42]Language and communication

The prefrontal cortex, particularly its ventral lateral portion (VLPFC), plays a central role in language production through Broca's area, encompassing Brodmann areas 44 and 45 in the left inferior frontal gyrus. This region is essential for articulating speech sounds and constructing syntactic structures, facilitating the grammatical organization of verbal output. Neuroimaging studies have demonstrated that activation in Broca's area increases during tasks requiring syntactic processing, such as generating complex sentences, underscoring its involvement in sequencing linguistic elements beyond mere motor control.[43][44] In semantic processing, the left inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) integrates conceptual meanings by interacting with the temporal lobe, enabling comprehension of word relationships and contextual interpretation. This connectivity supports the retrieval and selection of semantic knowledge, where the IFG modulates access to stored representations in the anterior temporal lobe during tasks like semantic judgment or ambiguity resolution. Functional MRI evidence shows that disruptions in this frontotemporal network impair the controlled retrieval of meanings, highlighting the IFG's role in resolving semantic competition.[45][46][47] Bilingualism exerts structural effects on the prefrontal cortex, promoting increased gray matter density in regions like the inferior frontal gyrus, which correlates with enhanced linguistic proficiency and cognitive flexibility. Longitudinal studies indicate that lifelong bilingual experience leads to greater gray matter volume in these areas, serving as a form of neural reserve that buffers age-related decline. This adaptation is particularly evident in early bilinguals, where denser prefrontal tissue supports efficient language switching.[48][49][50] The right prefrontal cortex contributes to nonverbal aspects of communication, including the interpretation of prosody—the rhythmic and intonational elements of speech—and gestures that convey emotional nuance. Activation in the right inferior frontal gyrus aids in decoding prosodic cues for affective intent, integrating them with facial expressions to form holistic social signals. Research using emotional prosody tasks reveals that this region enhances the processing of nonverbal vocalizations, distinct from verbal content analysis.[51][52][53] Additionally, prefrontal executive control briefly supports multilingual language switching by inhibiting irrelevant lexical items, though this overlaps minimally with core production mechanisms.Development and plasticity

Prenatal and postnatal development

The development of the prefrontal cortex (PFC) begins prenatally with neurogenesis initiating around the eighth gestational week in humans, as neural tissue is induced from the ectoderm. Neurogenesis peaks during the second trimester, specifically between weeks 13 and 16, primarily in the ventricular zone of the dorsal telencephalon, where progenitor cells proliferate to generate neurons destined for the PFC.[54] Following their birth, these neurons undergo radial migration in an inside-out pattern, traveling from the ventricular zone to form the cortical layers, with most settling by weeks 25–26 of gestation to establish the basic cytoarchitecture of the PFC.[54] Postnatally, PFC maturation is protracted, extending into the mid-20s, with structural maturation generally completing around age 25. This completion is associated with significant enhancements in self-control, metacognition, and self-recognition. Maturation is characterized by ongoing synaptogenesis that peaks around age 3.5 years, reaching a density of approximately 750 million synapses per cubic millimeter, followed by extensive synaptic pruning that refines connections through adolescence and into the third decade of life, particularly in layer III of the cortex. Sex differences emerge, with females showing accelerated myelination and synaptic pruning compared to males, influencing the timing of executive function maturation.[54] Myelination also progresses during this period, beginning in childhood and continuing into early adulthood, which increases white matter volume and enhances connectivity efficiency within the PFC.[54] Subregions such as the dorsolateral PFC mature last, contributing to the delayed refinement of higher-order functions.[54] Sensitive periods for the emergence of executive functions, such as cognitive flexibility and working memory, occur around ages 3–7, when prefrontal recruitment strengthens in response to tasks requiring inhibition and attention, coinciding with structural growth spurts in the PFC.[55][56] Genetic factors, including the transcription factor FOXP2, play a key role in PFC development relevant to language processing; FOXP2 is expressed in cortical projection neurons during embryogenesis, regulating neurogenesis, neuronal migration, and downstream networks for neurite outgrowth, with mutations linked to speech and language disorders that impair phonological working memory and vocal circuit formation.[57][58][59]Neuroplasticity and aging

Although structural maturation of the PFC is largely complete by around age 25, the cortex maintains significant neuroplasticity throughout adulthood and into old age. This allows for lifelong updates and modifications to self-recognition through experience, learning, and environmental influences. The notion that self-recognition remains "unchanged" or fixed after structural maturation is a misconception; while changes become more gradual post-maturity, they are not precluded and can occur via ongoing neuroplastic mechanisms. The prefrontal cortex (PFC) maintains neuroplasticity into adulthood through synaptic mechanisms such as long-term potentiation (LTP), which enhances the strength of glutamatergic synapses in response to repeated neural activity. In the PFC, LTP is particularly modulated by dopamine D1 receptor activation, which facilitates the maintenance of synaptic potentiation and supports executive functions like working memory.[60] This process involves calcium influx and activation of downstream signaling pathways, including AMPA receptor trafficking, enabling adaptive rewiring of PFC circuits.[61] Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) further mediates PFC plasticity by promoting dendritic spine growth, synaptogenesis, and the consolidation of LTP. BDNF signaling in the PFC, via its high-affinity receptor TrkB, enhances neuronal survival and synaptic efficacy, counteracting potential declines in trophic support during adulthood.[62] Down-regulation of BDNF in the PFC has been linked to reduced plasticity, underscoring its role in sustaining cognitive flexibility.[63] Aging impacts PFC plasticity, with the dorsolateral PFC (DLPFC) showing progressive gray matter volume loss of approximately 1-2% per decade after age 40, as observed in longitudinal MRI studies. This atrophy correlates with diminished synaptic density and myelin integrity, contributing to slower executive processing, though cognitive reserve—built through lifelong education and stimulation—can buffer these effects by enhancing neural efficiency.[64] Such reserve mechanisms allow individuals with higher reserve to maintain performance despite structural changes.[65] Interventions like aerobic exercise and cognitive training can enhance PFC plasticity in aging populations by leveraging hippocampal-PFC connections. Aerobic exercise increases PFC gray matter volume and strengthens functional links between the hippocampus and PFC, promoting BDNF expression and neurogenesis that support memory and executive functions.[66] Combined with cognitive training, these approaches induce cortical thickening in fronto-cingulate regions, improving working memory through synergistic neuroplastic changes.[67] Short-term exercise programs, such as 3 months of moderate activity, have demonstrated measurable prefrontal plasticity in older adults, associated with better cognitive outcomes. Recent post-2023 studies using functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) have illuminated intrinsic connectivity changes in the aging PFC. Resting-state fNIRS analyses reveal reduced functional connectivity within PFC networks in older adults during motor and cognitive tasks, reflecting diminished synchronization that aligns with executive decline.[68] These findings highlight age-related shifts in PFC intrinsic networks, with potential for interventions to restore connectivity patterns.[69] The PFC also demonstrates reversibility in functional impairments arising from lifestyle factors such as chronic sleep deprivation, excessive screen time (e.g., short video scrolling), and poor diets high in sugars. These habits can reduce self-control, attention, and decision-making by promoting dopamine dependency and sleep deficits, with combined habits potentially amplifying these effects. However, most such impairments are functional and reversible without permanent damage through neuroplasticity, via strategies including habit moderation, adequate sleep, limited screen exposure, healthy eating, and exercise, which restore synaptic efficiency and dopamine balance.[70][71][72][73][74]Evolutionary aspects

Comparative anatomy across species

The prefrontal cortex (PFC) shows marked structural differences across species, underscoring its evolutionary expansion in association with advanced cognitive processing. In primates, the granular PFC, characterized by a well-developed granular layer IV, occupies a substantially larger proportion of the total cerebral cortex compared to non-primates; for instance, it constitutes approximately 29% of the cortex in humans, in contrast to about 11% in macaques.[13][75] This disparity highlights the primate-specific enlargement of prefrontal regions, which is less pronounced in prosimians and absent in non-primate mammals where prefrontal areas are predominantly agranular.[15] In rodents, the functional equivalents of the PFC are primarily the prelimbic and infralimbic cortices within the medial prefrontal region, which exhibit connectivity patterns analogous to the primate anterior cingulate and dorsolateral PFC but lack the extensive granular architecture.[76][77] These rodent areas are involved in basic executive-like functions, yet they represent only a small fraction of the overall cortex, typically around 5-7%, reflecting a more rudimentary organization suited to simpler behavioral demands.[15] Evolutionary patterns of PFC expansion are particularly evident in the disproportionate growth of specific subregions in humans relative to other primates. The orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) in humans are significantly larger—up to 1.9-fold greater in proportional volume compared to macaques—facilitating enhanced integration of sensory, emotional, and decision-making processes for complex behaviors.[75][78] This expansion is supported by increased cortical folding and white matter volume in these areas, distinguishing human PFC from that of closer relatives like chimpanzees, where such regions are intermediate in size.[79] Recent investigations into mesoscale connectivity have further illuminated cross-species similarities and differences, particularly in primates. A 2025 study using infrared neural stimulation-functional MRI (INS-fMRI) in macaques revealed intricate functional connections between the amygdala and PFC subregions, including the auditory and prefrontal cortices, demonstrating how these circuits operate at a mesoscale level to integrate emotional and cognitive signals—patterns that are conserved but amplified in humans.[80]Role in human-specific cognition

The medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) plays a pivotal role in abstract reasoning and future planning through its involvement in episodic prospection, the mental simulation of potential future events that enables humans to anticipate and prepare for distant outcomes.[81] This process integrates autobiographical memory with imagination, allowing for the construction of detailed, self-relevant scenarios that guide decision-making and goal-directed behavior in uniquely human ways.[81] Neuroimaging studies demonstrate that mPFC activation during prospection modulates delay discounting, reducing impulsive choices by enhancing the perceived value of future rewards.[81] In cultural learning, the prefrontal cortex facilitates imitation and adherence to social norms, integrating observational learning with normative evaluation to transmit complex cultural knowledge across generations.[82] This involves prefrontal regions coordinating with other networks to encode and enforce cooperative rules, such as fairness in social exchanges, which underpin human societal structures.[82] For instance, prefrontal activity during norm compliance tasks reveals heightened sensitivity to violations, promoting conformity and collective behavior essential for large-scale human collaboration.[82] Creativity and problem-solving in humans rely on the frontopolar cortex (Brodmann area 10) for divergent thinking, where it supports the generation of novel ideas by integrating disparate concepts and exploring multiple solution paths.[83] This region exhibits increased activation and connectivity during tasks requiring remote associations, enabling breakthroughs in innovation that distinguish human cognition.[84] Functional MRI evidence shows that left frontopolar cortex activity correlates with creative semantic integration, facilitating the recombination of ideas into original outcomes.[84] Genetic correlates of these human-specific functions include human accelerated regions (HARs), non-coding DNA sequences that have rapidly evolved in humans and drive enhanced gene expression in the prefrontal cortex.01123-0) HARs function as transcriptional enhancers during neurodevelopment, promoting cortical expansion and connectivity in prefrontal areas linked to advanced cognition.[85] For example, HAR-associated genes show elevated expression in human fetal brain tissue, particularly in progenitors contributing to prefrontal subregions, underscoring their role in evolutionary adaptations for complex mental faculties.[86] Humans exhibit enlarged subregions of the prefrontal cortex, such as area 10, relative to other primates, supporting these specialized cognitive capacities.[85]Clinical significance

Associated disorders

The prefrontal cortex (PFC) is implicated in a range of neurological and psychiatric disorders characterized by dysfunction in executive control, emotional regulation, and decision-making processes. These conditions often involve structural atrophy, hypoactivity, or dysregulation in specific PFC subregions, leading to impaired cognitive and behavioral outcomes. Key examples include schizophrenia, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), major depressive disorder (MDD), and frontotemporal dementia (FTD), where PFC alterations contribute to core symptomatology.[87][88][36][89] In schizophrenia, hypoactivity in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) is a hallmark feature, associated with deficits in working memory and cognitive control. Neuroimaging studies consistently demonstrate reduced DLPFC activation during cognitive tasks in affected individuals, contributing to disorganized thinking and negative symptoms. This inefficiency persists even when performance is matched to healthy controls, underscoring a core pathophysiological role for DLPFC dysfunction.[87][90][91] ADHD is marked by executive function deficits linked to prefrontal cortex hypoactivation and structural abnormalities, particularly in the right PFC. These impairments manifest as difficulties in attention, inhibition, and planning, mirroring symptoms observed in patients with PFC lesions. Functional imaging reveals reduced PFC engagement during tasks requiring sustained attention, supporting the role of dopaminergic dysregulation in this circuitry.[88][92][93] Major depressive disorder involves dysregulation of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), often characterized by hyperactivity that disrupts emotion regulation and reward processing. This leads to persistent negative affect and anhedonia, with vmPFC alterations correlating with symptom severity. Structural and functional changes in vmPFC are evident in both acute and chronic phases, highlighting its role in affective dysregulation.[36][94][95] Frontotemporal dementia, particularly the behavioral variant (bvFTD), features prominent atrophy in the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), resulting in profound social and behavioral changes. OFC volume loss correlates with disinhibition and loss of empathy, distinguishing bvFTD from other dementias. Neuroimaging confirms bilateral OFC thinning as an early marker, progressing to widespread frontotemporal involvement.[96][89][97] Lesions or damage to the OFC are strongly associated with increased impulsivity, including poor decision-making and socially inappropriate behavior. Patients exhibit heightened sensitivity to immediate rewards and reduced aversion to negative outcomes, as evidenced by performance on delay-discounting tasks. In contrast, medial PFC (mPFC) damage, particularly in the ventromedial region, leads to apathy, characterized by diminished motivation and goal-directed activity. This manifests as emotional blunting and reduced initiative, linked to disrupted valuation processes in mPFC circuits.[98][99][100][101] Prefrontal cortex involvement is prevalent in traumatic brain injury (TBI), with frontal injuries often resulting from coup-contrecoup mechanisms, contributing to executive and behavioral sequelae and leading to persistent cognitive impairments in a significant proportion of survivors.[102][103][104] Research from 2023 onward has established links between long COVID and PFC inflammation, with neuroimaging showing structural changes such as increased cortical thickness and elevated inflammatory markers in prefrontal regions among survivors as of 2025. This neuroinflammation contributes to cognitive fog and executive dysfunction, persisting beyond acute infection and affecting approximately 10-20% of COVID-19 cases overall, with cognitive symptoms in 20-50% of those with long COVID.[105][106][107][108]Diagnostic and therapeutic approaches

Diagnostic approaches to prefrontal cortex (PFC) impairments primarily involve neuroimaging techniques and neuropsychological assessments to evaluate activation patterns, functional connectivity, and executive function deficits. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) is widely used to map PFC activation during cognitive tasks, revealing hypoactivation in the dorsolateral PFC (DLPFC) associated with executive dysfunction in conditions like major depressive disorder.[109] Electroencephalography (EEG) provides temporal resolution for assessing oscillatory activity, such as theta power in the anterior PFC during executive tasks, which correlates with working memory and inhibitory control impairments.[110] Neuropsychological tests, including the Tower of London task, quantify planning and problem-solving abilities reliant on PFC networks, with prolonged completion times indicating orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) involvement in decision-making deficits.[111] Therapeutic interventions target PFC circuitry to restore function and alleviate symptoms in associated disorders. Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) applied to the left DLPFC enhances cortical excitability and connectivity, demonstrating efficacy in reducing depressive symptoms by modulating frontostriatal pathways.[112] Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) promotes PFC plasticity through repeated exposure and cognitive restructuring, increasing gray matter volume in prefrontal regions and normalizing limbic-prefrontal interactions in anxiety disorders.[113] Pharmacological treatments include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which elevate serotonin levels to modulate OFC activity, improving emotional regulation in obsessive-compulsive disorder.[114] Stimulants like methylphenidate boost dopamine transmission in the PFC, enhancing attention and executive control in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).[115] Non-pharmacological lifestyle modifications, such as improving sleep hygiene, reducing excessive screen time, adopting a balanced diet low in sugars, and engaging in regular exercise, leverage the neuroplasticity of the PFC to reverse functional deficits in executive functions like self-control, attention, and decision-making. Neuroimaging studies demonstrate that these interventions can restore PFC activation and connectivity; for instance, recovery sleep reverses sleep deprivation-induced hypoactivation and increased brain age predictions in the PFC, while diet and exercise interventions improve cognitive performance through enhanced prefrontal structure and function in older adults with mild cognitive impairment.[70][116][117] Emerging approaches leverage advanced neuromodulation techniques for precise PFC circuit repair. Optogenetics in animal models enables targeted activation or inhibition of PFC neurons, restoring circuit dynamics in depression-like behaviors by manipulating prefrontal-limbic projections. As of 2025, clinical translation remains limited to preclinical validation, with ongoing research exploring non-invasive optogenetic-inspired methods for neurodegenerative conditions.[118][119]History

Early discoveries

One of the earliest documented cases suggesting the role of the frontal lobes in personality and behavior occurred in 1848, when Phineas Gage, a 25-year-old railroad foreman, suffered a traumatic injury from an iron tamping rod that passed through his left frontal lobe. The accident dramatically altered Gage's temperament from responsible and socially adept to impulsive and profane, highlighting how frontal damage could disrupt executive control without impairing basic motor or sensory functions.[120] In 1861, French neurologist Paul Broca advanced the understanding of frontal lobe specialization by localizing articulate speech production to the posterior inferior frontal gyrus (Broca's area, corresponding to Brodmann areas 44 and 45), based on postmortem examination of a patient with aphasia. Broca's observation of a lesion in this region of the left hemisphere in a patient who could comprehend language but not produce fluent speech provided seminal evidence for cortical localization of higher cognitive functions within the frontal cortex.[121] Building on these clinical insights, early 20th-century experimental work by American physiologist John Fulton and psychologist Carlyle Jacobsen in the 1930s demonstrated the prefrontal cortex's involvement in executive processes through ablation studies in primates. In their 1935 experiments, bilateral prefrontal lobectomies in chimpanzees and monkeys resulted in severe impairments in delayed response tasks and abstract reasoning, while leaving immediate sensory-motor abilities intact; these deficits underscored the region's role in planning and behavioral inhibition.[122] Concurrently, neurologist Richard Brickner's 1934 analysis of a human patient with partial bilateral frontal lobectomy due to a tumor revealed profound deficits in the "abstract attitude," the capacity to form generalizations and shift conceptual sets, further linking prefrontal lesions to disruptions in higher-order cognition like foresight and synthesis. Brickner's detailed behavioral assessments showed preserved concrete thinking but impaired ability to categorize or anticipate outcomes, reinforcing the emerging view of the prefrontal cortex as central to integrative mental functions.[123]Etymology and modern terminology