Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

United States Attorney

View on Wikipedia

United States attorneys are officials of the U.S. Department of Justice who serve as the chief federal law enforcement officers in each of the 94 U.S. federal judicial districts. Each U.S. attorney serves as the United States' chief federal criminal prosecutor in their judicial district and represents the U.S. federal government in civil litigation in federal and state court within their geographic jurisdiction. U.S. attorneys must be nominated by the president and confirmed by the Senate, after which they serve four-year terms.

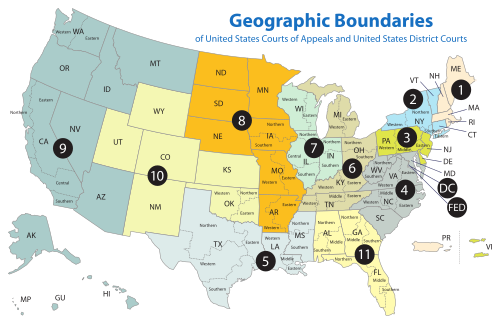

Currently, there are 93 U.S. attorneys in 94 district offices located throughout the United States, Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Guam, and the Northern Mariana Islands. One U.S. attorney is assigned to each of the judicial districts, with the exception of Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands, where a single U.S. attorney serves both districts. Each U.S. attorney is the chief federal law enforcement officer within a specified jurisdiction, acting under the guidance of the United States Attorneys' Manual.[1] They supervise district offices with as many as 350 assistant U.S. attorneys (AUSAs) and as many as 350 support personnel.[2]

U.S. Attorney's Offices are staffed mainly by assistant U.S. attorneys (AUSA). Often colloquially called "federal prosecutors", assistant U.S. attorneys are government lawyers who act as prosecutors in federal criminal trials and as the United States federal government's lawyers in civil litigation in which the United States is a party. In carrying out their duties as prosecutors, AUSAs have the authority to investigate persons, issue subpoenas, file formal criminal charges, plea bargain with defendants, and grant immunity to witnesses and accused criminals.[3]

U.S. attorneys and their offices are part of the Department of Justice. U.S. attorneys receive oversight, supervision, and administrative support services through the Justice Department's Executive Office for United States Attorneys. Selected U.S. attorneys participate in the Attorney General's Advisory Committee of United States Attorneys.

History and statutory authority

[edit]The Office of the United States Attorney was created by the Judiciary Act of 1789, along with the office of Attorney General and United States Marshal. The same act also specified the structure of the Supreme Court of the United States and established inferior courts making up the United States Federal Judiciary, including a district court system. Thus, the office of U.S. Attorney is older than the Department of Justice. The Judiciary Act of 1789 provided for the appointment in each judicial district of a "Person learned in the law to act as attorney for the United States...whose duty it shall be to prosecute in each district all delinquents for crimes and offenses cognizable under the authority of the United States, and all civil actions in which the United States shall be concerned..." Prior to the existence of the Department of Justice, the U.S. attorneys were independent of the attorney general, and did not come under the AG's supervision and authority until 1870, with the creation of the Department of Justice.[4][5]

Appointment

[edit]U.S. attorneys are appointed by the president of the United States[6] for a term of four years,[7] with appointments subject to confirmation by the Senate. A U.S. attorney continues in office, beyond the appointed term, until a successor is appointed and qualified.[8] By law, each United States attorney is subject to removal by the president.[9] The attorney general has had the authority since 1986 to appoint interim U.S. attorneys to fill a vacancy.

United States attorneys controversy

[edit]| 2006 dismissal of U.S. attorneys controversy |

The governing statute, 28 U.S.C. § 546 provided, up until March 9, 2006:

(c) A person appointed as United States attorney under this section may serve until the earlier of—

- (1) the qualification of a United States attorney for such district appointed by the President under section 541 of this title; or

- (2) the expiration of 120 days after appointment by the Attorney General under this section.

(d) If an appointment expires under subsection (c)(2), the district court for such district may appoint a United States attorney to serve until the vacancy is filled. The order of appointment by the court shall be filed with the clerk of the court.

On March 9, 2006, President George W. Bush signed into law the USA PATRIOT and Terrorism Prevention Reauthorization Act of 2005[10] which amended Section 546 by striking subsections (c) and (d) and inserting the following new subsection:

(c) A person appointed as United States attorney under this section may serve until the qualification of a United States Attorney for such district appointed by the President under section 541 of this title.

This, in effect, extinguished the 120-day limit on interim U.S. attorneys, and their appointment had an indefinite term. If the president failed to put forward any nominee to the Senate, then the Senate confirmation process was avoided, as the Attorney General-appointed interim U.S. attorney could continue in office without limit or further action. Related to the dismissal of U.S. attorneys controversy, in March 2007 the Senate and the House voted to re-instate the 120-day term limit on interim attorneys via the Preserving United States Attorney Independence Act of 2007.[11] The bill was signed by President George W. Bush, and became law in June 2007.[12]

History of interim U.S. attorney appointments

[edit]Senator Dianne Feinstein (D, California), summarized the history of interim United States Attorney appointments, on March 19, 2007 in the Senate.[13]

When first looking into this issue, I found that the statutes had given the courts the authority to appoint an interim U.S. attorney and that this dated back as far as the Civil War. Specifically, the authority was first vested with the circuit courts in March 1863.

Then, in 1898, a House of Representatives report explained that while Congress believed it was important to have the courts appoint an interim U.S. attorney:

"There was a problem relying on circuit courts since the circuit justice is not always to be found in the circuit and time is wasted in ascertaining his whereabouts."

Therefore, at that time, the interim appointment authority was switched to the district courts; that is, in 1898 it was switched to the district courts.

Thus, for almost 100 years, the district courts were in charge of appointing interim U.S. attorneys, and they did so with virtually no problems. This structure was left undisturbed until 1986 when the statute was changed during the Reagan administration. In a bill that was introduced by Senator Strom Thurmond, the statute was changed to give the appointment authority to the Attorney General, but even then it was restricted and the Attorney General had a 120-day time limit. After that time, if a nominee was not confirmed, the district courts would appoint an interim U.S. attorney. The adoption of this language was part of a larger package that was billed as technical amendments to criminal law, and thus there was no recorded debate in either the House or the Senate and both Chambers passed the bill by voice vote.

Then, 20 years later, in March 2006 – again without much debate and again as a part of a larger package – a statutory change was inserted into the PATRIOT Act reauthorization. This time, the Executive's power was expanded even further, giving the Attorney General the authority to appoint an interim replacement indefinitely and without Senate confirmation.

Role of U.S. attorneys

[edit]The U.S. attorney is both the primary representative and the administrative head of the Office of the U.S. Attorney for the district. The U.S. Attorney's Office (USAO) is the chief prosecutor for the United States in criminal law cases, and represents the United States in civil law cases as either the defendant or plaintiff, as appropriate.[14][15] However, they are not the only ones that may represent the United States in Court. In certain circumstances, using an action called a qui tam, any U.S. citizen, provided they are represented by an attorney, can represent the interests of the United States, and share in penalties assessed against guilty parties.

As chief federal law enforcement officers, U.S. attorneys have authority over all federal law enforcement personnel within their districts and may direct them to engage, cease or assist in investigations.[citation needed] In practice, this has involved command of Federal Bureau of Investigation assets but also includes other agencies under the Department of Justice, such as the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms and Drug Enforcement Administration.[citation needed] Additionally, U.S. attorneys cooperate with other non-DOJ law enforcement agencies – such as the United States Secret Service and Immigration and Customs Enforcement – to prosecute cases relevant to their jurisdictional areas.

The U.S. attorney for the District of Columbia has the additional responsibility of prosecuting local criminal cases in the Superior Court of the District of Columbia, the equivalent of a municipal court for the national capital. The Superior Court is a federal Article I court.[16]

Executive Office for United States Attorneys

[edit]The Executive Office for United States Attorneys (EOUSA)[17] provides the administrative support for the 93 United States attorneys (encompassing 94 United States Attorney offices, as the Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands has a single U.S. attorney for both districts), including:

- General executive assistance and direction,

- Policy development,

- Administrative management direction and oversight,

- Operational support,

- Coordination with other components of the United States Department of Justice and other federal agencies.

These responsibilities include certain legal, budgetary, administrative, and personnel services, as well as legal education.

The EOUSA was created on April 6, 1953, by Attorney General Order No. 8-53 to provide for close liaison between the Department of Justice in Washington, DC, and the 93 U.S. attorneys located throughout the 50 states, the District of Columbia, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. It was organized by Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals judge James R. Browning, who also served as its first chief.

List of current U.S. attorneys' offices

[edit]Note: Except as indicated parenthetically, the foregoing links are to the corresponding district court, rather than to the U.S. Attorney's Office.

Defunct U.S. attorneys' offices

[edit]- U. S. Attorney for the District of Michigan (February 24, 1863)[18]

- U. S. Attorney for the Eastern District of South Carolina (October 2, 1965)

- U. S. Attorney for the Western District of South Carolina (October 2, 1965)

- U. S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Illinois (October 2, 1978; succeeded by the Central District of Illinois)

- U. S. Attorney for the Panama Canal Zone (March 31, 1982)

- U. S. Attorney for the District of Indiana

- U.S. Attorney for the District of Washington

- United States Attorney for the District of Arkansas

- United States Attorney for the Western District of Florida

- United States Attorney for the Eastern District of Florida

- United States Attorney for the District of Georgia

- United States Attorney for the District of Illinois

- United States Attorney for the Territory of Iowa

- United States Attorney for the District of Kentucky

- United States Attorney for the District of Louisiana

- United States Attorney for the District of Michigan

- United States Attorney for the District of Mississippi

- United States Attorney for the District of Missouri

- United States Attorney for the Territory of New Mexico

- United States Attorney for the District of New York

- United States Attorney for the District of North Carolina

- United States Attorney for the Territory of Dakota

- United States Attorney for the District of Ohio

- United States Attorney for the District of Oklahoma

- United States Attorney for the District of South Carolina

- United States Attorney for the District of Tennessee

- United States Attorney for the District of Texas

- United States Attorney for the District of Virginia

- United States Attorney for the District of West Virginia

- United States Attorney for the District of Wisconsin

- United States Attorney for the District of China (Shanghai) (1928–1937)

- United States Attorney for the District of Alaska, Sitka

- First District, Juneau (1898–1957)

- Second District, Nome (1900–1953)

- Third District, Eagle, Fairbanks, Valdez, Anchorage (1900–1960)

- Fourth District, Fairbanks (1909–1960)

See also

[edit]- List of United States attorneys appointed by Joe Biden

- List of United States attorneys appointed by Donald Trump

- Dismissal of U.S. attorneys controversy (2007)

- 2017 dismissal of U.S. attorneys

- Special counsel

- United States Attorney General

- United States Department of Justice

- Law officers of the Crown

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "US Attorneys' Manual". usdoj.gov. February 19, 2015.

- ^ "United States Attorney Office for the District of Columbia". usdoj.gov. Retrieved November 10, 2007.

- ^ http://www.americanbar.org/publications/criminal_justice_section_archive/crimjust_standards_pinvestigate.html Standards on Prosecutorial Investigations

- ^ Sisk, Gregory C. (2006). John Steadman; David Schwartz; Sidney B. Jacoby (eds.). Litigation With the Federal Government (2nd ed.). ALI-ABA (American Law Institute – American Bar Association). pp. 12–14. ISBN 0-8318-0865-9.

- ^ Sisk, Gregory C. (2006). Partial access online. Ali-Aba. ISBN 9780831808655.

- ^ 28 U.S.C. § 541(a).

- ^ 28 U.S.C. § 541(b).

- ^ 28 U.S.C. § 541(b)

- ^ 28 U.S.C. § 541(c).

- ^ "Pub. L. 109–177, title V, § 502" (PDF). U.S. Government Publishing Office. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- ^ "Preserving United States Attorney Independence Act of 2007" (PDF). Congress.gov. Retrieved January 30, 2024.

- ^ "House votes to strip U.S. Attorney provision". Think Progress. March 26, 2007.

- ^ Congressional Record, March 19, 2007, 2007 Congressional Record, Vol. 153, Page S3240 -S3241)

- ^ see generally 28 U.S.C. § 547

- ^ "US Attorneys' Manual. Title 1, section 1-2.500". Department of Justice. November 2003. Archived from the original on April 1, 2005.

- ^ "William Roshko". Judgepedia. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013.

- ^ "Justice Manual, Title 3: EOUSA". justice.gov. February 19, 2015. Archived from the original on November 7, 2023.

- ^ "History of the Federal Judiciary". Federal Judicial Center. Retrieved June 26, 2013.

External links

[edit]- US Attorneys Office Archived November 20, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- United States Attorneys Mission Statement

- United States Attorneys' Manual

- Memorandum on Starting Date for Calculating the Term of an Interim U.S. Attorney Archived December 16, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- D.C. Superior Court Division Archived January 2, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Index of prosecuting offices in all state and federal jurisdictions, and some foreign jurisdictions. Archived July 23, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Lawyers New U.S. Attorney

United States Attorney

View on GrokipediaOverview and Purpose

Definition and Core Functions

The United States Attorney serves as the chief federal prosecutor and legal representative of the United States government within a designated federal judicial district, operating under the authority of the Department of Justice (DOJ).[5] Appointed by the President with the advice and consent of the Senate pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 541, there are 93 such attorneys, each responsible for one of the 94 federal judicial districts, with the districts of Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands sharing a single office.[5][8] Their role embodies the executive branch's mandate to "faithfully execute" federal laws, focusing on enforcement rather than policy advocacy.[5] Core functions encompass prosecuting all federal criminal offenses committed within the district or subject to U.S. jurisdiction, as delineated in 28 U.S.C. § 547(1).[9] This includes coordinating multi-agency investigations involving federal, state, and local law enforcement to address crimes such as drug trafficking, terrorism, public corruption, and violent offenses with interstate elements.[4] In civil matters, United States Attorneys prosecute or defend suits in which the government is a party, including debt collection, asset forfeiture, and defense against claims under laws like the Federal Tort Claims Act, per 28 U.S.C. § 547(2).[10] They also handle appeals to circuit courts and seek injunctive relief or penalties for regulatory violations.[9] Additional duties involve representing federal agencies in district courts, providing legal advice to federal law enforcement, and ensuring compliance with ethical standards under DOJ guidelines.[6] United States Attorneys maintain supervisory authority over Assistant United States Attorneys and support staff, typically numbering from dozens to over 300 per office depending on district size and caseload.[11] These functions prioritize empirical case merits over discretionary non-prosecution, though prosecutorial discretion exists within statutory bounds and Attorney General directives.[5]Jurisdictional Scope and Number of Offices

United States Attorneys exercise prosecutorial and litigating authority within the geographic boundaries of their assigned federal judicial districts, as delineated by federal statute.[5] These districts comprise 94 separate judicial divisions established under Title 28 of the United States Code, covering the 50 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and certain territories including Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, and the United States Virgin Islands.[3] Within their districts, U.S. Attorneys serve as the primary federal representatives in district courts, handling criminal prosecutions, civil enforcement actions, and defense of federal interests, subject to oversight by the Attorney General.[12] The structure maintains one U.S. Attorney office per district in most cases, resulting in 93 operational offices nationwide.[13] This configuration accounts for the combined jurisdiction of a single U.S. Attorney serving both the District of Guam and the District of the Northern Mariana Islands, as authorized by specific territorial statutes.[5] Each office is staffed with Assistant United States Attorneys who assist in executing these responsibilities, ensuring localized enforcement of federal law while adhering to national policies from the Department of Justice.[14] The district-based scope prevents overlap with state jurisdictions and aligns federal prosecutorial efforts with the territorial limits of Article III courts.[15]Historical Foundations

Origins in the Early Republic

The office of United States Attorney originated with the Judiciary Act of 1789, passed by the First Congress and signed into law by President George Washington on September 24, 1789.[16] This foundational statute established the lower federal courts, including district courts in each state, and created the position of an attorney for the United States—one for each of the thirteen initial judicial districts—to represent federal interests in litigation.[17] Section 35 of the Act specified that these officers, described as "a meet person learned in the law," would be appointed by the President, confirmed by the Senate where required, and removable at presidential discretion, reflecting the framers' intent to embed executive oversight in federal prosecution amid a decentralized judiciary.[18] President Washington nominated the first district attorneys on September 24, 1789, coinciding with the Act's enactment, to fill these roles immediately as the federal court system commenced operations.[19] Their core duties encompassed prosecuting federal crimes—though federal criminal statutes were sparse, limited mainly to piracy, counterfeiting, and offenses against customs laws—defending the United States in civil suits, collecting debts owed to the government, and advising district judges and marshals on legal matters.[18] Compensation derived from fees for services rendered, such as per-case payments for prosecutions or defenses, rather than fixed salaries, which incentivized efficiency but tied their livelihoods to caseload volume in an era of minimal federal enforcement needs.[18] These early attorneys operated with considerable autonomy, as the newly created Attorney General position—held first by Edmund Randolph—lacked statutory supervisory authority over them, leading to fragmented coordination until the Treasury Department assumed nominal oversight in the 1790s.[19] In practice, district attorneys often maintained private practices, handling federal duties part-time amid jurisdictional tensions with state courts and the absence of a unified Department of Justice, which underscored the Early Republic's emphasis on local adaptation over centralized control in legal administration.[18]Key Legislative Milestones

The Judiciary Act of 1789 established the office of United States Attorney, originally termed "district attorney," for each of the thirteen federal judicial districts, tasking them with prosecuting offenses against the United States and handling civil suits involving federal interests.[16][20] Signed into law by President George Washington on September 24, 1789, the act provided for presidential nomination with Senate confirmation, marking the initial statutory framework for federal prosecutorial authority independent of state systems.[17] This legislation responded to the Constitution's directive for a uniform federal judiciary by creating executive-branch officers to enforce national laws, with the first thirteen appointees nominated the same day the act passed.[19] Subsequent reforms addressed fragmented oversight, as early US Attorneys reported variably to the Secretary of State or Solicitor of the Treasury, leading to inconsistent enforcement. The Act of August 2, 1861 (12 Stat. 285), shifted supervisory control to the Attorney General, empowering that office to direct US Attorneys in litigation and requiring reports on cases, amid Civil War demands for coordinated federal prosecutions.[19][21] This change centralized authority without altering core appointment processes, enabling more uniform application of federal law across districts.[22] The Act to Establish the Department of Justice, signed by President Ulysses S. Grant on June 22, 1870 (16 Stat. 162), further integrated US Attorneys into a dedicated executive department, formalizing the Attorney General's superintendence over all federal legal officers and transferring related functions from treasury and other agencies.[23][22] With 85 employees initially, the DOJ assumed direct management of US Attorneys' operations, including budgeting and policy guidance, to remedy prior inefficiencies in prosecuting interstate crimes and civil enforcement.[24] This statute enhanced causal coordination by vesting the AG with explicit duties to advise the president on legal matters and supervise district-level execution, laying groundwork for modern federal prosecutorial hierarchy.[23] Later amendments refined vacancy fillings and tenure; for instance, 1986 legislation under 28 U.S.C. § 546 authorized the Attorney General to appoint interim US Attorneys for up to 120 days pending Senate-confirmed replacements, addressing delays in full appointments while preserving presidential primacy.[25] These milestones collectively evolved the role from decentralized district enforcers to a structured component of national law administration, prioritizing empirical uniformity in federal justice over localized variances.Legal Authority and Framework

Statutory Basis Under Title 28

The statutory framework for United States Attorneys is codified in Chapter 35 of Title 28 of the United States Code, spanning sections 541 through 549, which outline the establishment, appointment, duties, and operational parameters of these offices.[26] Section 541(a) mandates that the President appoint, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, one United States Attorney for each of the 94 federal judicial districts established under Chapter 5 of the same title.[3] These appointments are for a term of four years, as specified in section 541(b), after which the Attorney General may direct the United States Attorney to continue serving until a successor is appointed or a vacancy is otherwise filled.[3] Section 547 enumerates the core duties of United States Attorneys, requiring them to prosecute all offenses against the United States; to prosecute or defend all civil actions, suits, or proceedings in which the United States participates, except as otherwise directed by the Attorney General; to represent the government before grand juries and in cases of habeas corpus where a prisoner is held under federal authority; and to perform other duties as prescribed by the Attorney General or required by law.[9] This section underscores the prosecutorial primacy of United States Attorneys in federal criminal matters, while allowing for Attorney General oversight in civil and specialized proceedings.[1] Additional provisions in Chapter 35 address support structures and contingencies. Section 543 authorizes United States Attorneys to appoint Assistant United States Attorneys, subject to Attorney General approval regarding numbers, qualifications, and salaries, ensuring adequate staffing for district operations. Section 546 governs vacancies, empowering the Attorney General to appoint interim United States Attorneys for up to 120 days in districts where the office becomes vacant, with further extensions possible through district court designation or Presidential appointment during Senate recess.[27] Sections 544 and 545 address special circumstances, such as assigning responsibilities in districts lacking a resident United States Attorney or authorizing deputies to act during absences. These mechanisms collectively ensure continuity and adaptability in federal enforcement without undermining the constitutional appointment process. The framework under Title 28 integrates United States Attorneys into the broader Department of Justice hierarchy, with section 548 requiring semi-annual reports to the Attorney General on cases and proceedings, and section 549 prohibiting private practice of law by these officers to maintain undivided loyalty to federal duties. This structure, rooted in post-Judiciary Act codifications, balances district-level autonomy with centralized supervision, reflecting congressional intent to enforce federal law efficiently across jurisdictions.Integration with the Department of Justice

United States Attorneys operate as a core component of the Department of Justice (DOJ), serving under the supervision and direction of the Attorney General, who holds ultimate authority over the department's administration, including the 94 offices of U.S. Attorneys.[28] This integration ensures that federal prosecutions and civil enforcement actions align with national priorities while allowing for district-specific discretion in resource allocation and case selection.[29] The Executive Office for United States Attorneys (EOUSA), established within the DOJ, provides centralized executive assistance, policy guidance, and oversight to these offices, facilitating coordination between headquarters and field operations.[2] Under 28 U.S.C. Chapter 35, U.S. Attorneys are statutorily positioned within the DOJ structure, with their duties outlined in sections such as § 547, which mandates prosecution of federal crimes, defense of U.S. civil actions, and collection of federal debts within their respective judicial districts. This framework embeds them in the DOJ's hierarchical chain, where they report significant cases, policy matters, and resource needs to EOUSA and relevant divisions like the Criminal or Civil Divisions, ensuring uniformity in legal standards across districts.[30] For instance, EOUSA maintains automated case management systems that aggregate data from all U.S. Attorneys' offices, enabling DOJ-wide monitoring of litigation trends and performance metrics.[31] Integration also involves operational collaboration with other DOJ entities, such as the Federal Bureau of Investigation for investigations and U.S. Marshals Service for enforcement, under the Attorney General's overarching directives.[32] While U.S. Attorneys retain prosecutorial independence in routine matters—exercising wide discretion to address local priorities—the Attorney General may intervene in high-profile or nationally significant cases to enforce departmental policies, as affirmed in DOJ organizational protocols.[33] This balance reflects the DOJ's design to combine centralized control with decentralized execution, mitigating risks of inconsistent application of federal law.[34]Appointment and Tenure

Presidential Nomination and Senate Confirmation

The appointment of United States Attorneys is authorized under Article II, Section 2 of the United States Constitution, which grants the President the power to nominate principal officers of the United States, subject to the Senate's advice and consent.[35] This process applies to United States Attorneys as heads of federal prosecutorial offices in each of the 94 judicial districts.[36] Specifically, 28 U.S.C. § 541(a) requires the President to appoint a United States Attorney for each judicial district "by and with the advice and consent of the Senate."[8] The nomination process commences when the President selects and formally submits a nominee's name to the Senate, typically after consultation with the Attorney General and consideration of recommendations from senators of the president's party representing the relevant state or district.[36] Upon receipt, the Senate assigns the nomination a number and refers it to the Senate Judiciary Committee, which conducts a review including background checks by the Federal Bureau of Investigation, financial disclosures, and ethics evaluations.[37] The committee may hold confirmation hearings where the nominee testifies on qualifications, prosecutorial philosophy, and policy priorities; these hearings assess legal experience, impartiality, and alignment with federal enforcement needs, though nominees are not statutorily required to possess bar membership or prior prosecutorial roles beyond general fitness standards.[38] Following committee markup and a vote—often reported favorably by voice or recorded tally—the nomination advances to the full Senate for debate and a simple majority confirmation vote, with the Vice President breaking ties if necessary.[36] Confirmations of United States Attorneys have historically been routine, with the Senate approving the vast majority without significant opposition, reflecting their role as executive-branch enforcers rather than independent judicial figures.[36] From 1989 to 2017, for instance, over 95% of nominees received committee approval without hearings in some administrations, though delays or rejections can occur amid partisan disputes over enforcement priorities or senatorial courtesy practices like blue slips from home-state senators. Upon Senate confirmation, the appointee assumes office for a four-year term under 28 U.S.C. § 541(b), during which they execute federal laws within their district.[8] Political considerations influence selections, as presidents often prioritize loyalists capable of advancing administration agendas, such as prioritizing certain criminal justice reforms or immigration enforcement, though nominees must demonstrate competence in federal litigation.Interim Appointments and Vacancy Procedures

Upon a vacancy in the office of United States Attorney, the Attorney General is authorized to appoint an interim United States Attorney under 28 U.S.C. § 546(a), who serves until the earlier of the qualification of a presidentially nominated and Senate-confirmed successor or the expiration of 120 days from the date of appointment.[27] This interim appointment mechanism ensures continuity in federal prosecutorial functions across the 94 judicial districts while a permanent replacement undergoes the standard nomination and confirmation process outlined in 28 U.S.C. § 541.[3] If the vacancy persists beyond the 120-day interim period appointed by the Attorney General, and no presidential nomination is pending or confirmed, the judges of the relevant United States District Court may appoint an interim United States Attorney under 28 U.S.C. § 546(d), with the appointment made by order filed with the clerk of the court; the appointee serves until a permanent United States Attorney qualifies or for 120 days from the court's appointment, whichever occurs first, and their authority derives from the court's order rather than a presidential commission, as the statute does not provide for or mention such a commission for court-appointed U.S. Attorneys, in contrast to presidential appointees under § 541.[27] This judicial appointment provision, added by the USA PATRIOT Improvement and Reauthorization Act of 2005 (Pub. L. No. 109-177), was designed to prevent indefinite executive control over vacancies but has been invoked sparingly, such as in isolated district-level cases where Senate confirmation delays extended beyond statutory limits. The Federal Vacancies Reform Act of 1998 (FVRA, 5 U.S.C. §§ 3345 et seq.) potentially overlaps with § 546, allowing the President to designate an acting United States Attorney from eligible senior Department of Justice officials, such as the Principal Deputy Assistant Attorney General or a first assistant in the office, for up to 210 days in the first year of a presidential term or 210 days generally, subject to extensions if a nomination is pending.[39] However, longstanding Department of Justice interpretations assert that § 546 provides the exclusive framework for United States Attorney vacancies, rendering FVRA inapplicable to override Attorney General or judicial authority.[40] Recent analyses, including Congressional Research Service reports, highlight unresolved legal questions regarding this interplay, particularly in scenarios where presidential acting designations might conflict with § 546's time limits or appointment sequences, as debated in contexts like post-2024 election transitions.[41] These tensions underscore potential constitutional challenges under the Appointments Clause, though courts have generally upheld § 546 mechanisms as consistent with inferior officer appointments when limited in duration.[42]Removal Practices and Presidential Discretion

United States Attorneys serve at the pleasure of the President and may be removed without cause or congressional approval, as explicitly provided in 28 U.S.C. § 541(c).[8] This statutory authority aligns with the broader constitutional removal power vested in the executive branch for principal officers, enabling the President to ensure faithful execution of laws through alignment with administration priorities.[43] The Supreme Court has upheld this at-will removal doctrine for such appointees, tracing back to Parsons v. United States (1897), which affirmed that United States Attorneys hold office subject to presidential discretion rather than fixed terms.[44] In practice, incoming presidents routinely exercise this discretion by requesting resignations from predecessor-appointed United States Attorneys to facilitate the installation of nominees better suited to current policy objectives, a tradition spanning administrations. For instance, upon taking office in January 2017, President Trump sought the resignations of all 93 sitting United States Attorneys by March 10, 2017, resulting in the departure of 46 Obama-era appointees, though some districts retained interim leadership longer due to confirmation delays. Mid-term removals also occur, often tied to performance issues or perceived misalignment, as seen in the George W. Bush administration's dismissal of seven United States Attorneys in December 2006, which prompted congressional scrutiny but did not alter the legal validity of the President's authority.[45] Presidential discretion in removals remains broad and largely insulated from judicial or legislative interference, with no statutory requirement for cause or notice, though ethical guidelines within the Department of Justice emphasize performance-based evaluations.[44] This flexibility underscores the political nature of the role, allowing the executive to direct federal enforcement priorities, such as shifting emphasis on immigration or corruption cases, without entrenched opposition from holdover prosecutors. Controversies, like the 2006-2007 firings, have highlighted tensions over motives—allegations of partisan purging versus legitimate oversight—but courts have consistently deferred to executive prerogative absent evidence of constitutional violation.[43]Responsibilities and Operations

Criminal Prosecution Priorities

United States Attorneys prioritize criminal prosecutions that align with federal interests, including offenses involving national security, interstate commerce, or threats beyond state capacity, as outlined in the Department of Justice's Principles of Federal Prosecution. These principles require assessing whether a case warrants federal involvement based on factors such as the seriousness of the offense, potential for deterrence, and resource allocation efficiency.[46] Prosecution is initiated only upon probable cause and evidence sufficient for conviction, with discretion to decline matters lacking substantial federal stakes or better suited for state handling or civil remedies.[46] District-level priorities are established by each United States Attorney in coordination with federal investigative agencies like the FBI, DEA, and ATF, tailoring efforts to local threats while adhering to national guidelines. Common focal areas include drug trafficking and organized crime under initiatives like the Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Forces (OCDETF), violent crime and gang activity through programs such as Project Safe Neighborhoods, public corruption, child exploitation, and cyber intrusions.[46] [47] These selections emphasize cases promoting respect for federal law and public safety, with documentation required for declinations to ensure accountability.[46] National priorities, directed by the Attorney General, reflect executive policy shifts across administrations. For instance, in fiscal year 2022, U.S. Attorneys handled over 70,000 criminal terminations, with prominent categories encompassing immigration violations (particularly in southwestern districts), drug offenses, and firearms prosecutions.[48] Recent 2025 guidance under Attorney General Pam Bondi refocused resources on combating transnational cartels, immigration enforcement, human trafficking, and protecting law enforcement from violence, including enhanced asset forfeiture against criminal organizations.[49] [50] This approach prioritizes high-impact deterrence over lower-level regulatory violations, aligning with statutory mandates under titles like 21 U.S.C. for controlled substances and 18 U.S.C. for racketeering.[46]Civil Litigation and Enforcement

United States Attorneys' offices manage civil litigation in federal district courts within their jurisdictions, prosecuting and defending cases where the federal government is a party, as authorized under 28 U.S.C. § 547.[1] This encompasses both defensive representation of the United States against claims and affirmative actions to enforce federal statutes and recover assets.[1] Each office's Civil Division oversees these efforts, handling a caseload that includes routine debt collection for administratively uncollectible amounts owed to the government, alongside more complex disputes.[1] In defensive litigation, United States Attorneys represent federal agencies and officials sued under statutes such as the Federal Tort Claims Act, Administrative Procedure Act, Freedom of Information Act, and federal employment discrimination laws.[51] Common cases involve challenges to immigration decisions, Social Security benefit denials, Medicare and Medicaid payment disputes, Privacy Act violations, and constitutional tort claims against government entities.[51] For example, civil Assistant United States Attorneys defend against lawsuits alleging misconduct by agencies like the Drug Enforcement Administration in asset forfeiture proceedings.[52] These defenses extend to appellate levels, including the relevant circuit courts, ensuring consistent application of federal law across districts.[51] Affirmative civil enforcement actions by United States Attorneys focus on recovering government funds lost to fraud or misconduct and imposing penalties for statutory violations.[53] Key areas include health care fraud under the False Claims Act, where offices pursue qui tam suits initiated by whistleblowers to address overbilling or kickbacks in federal programs; the District of Columbia U.S. Attorney's Office, for instance, maintains strong whistleblower partnerships yielding significant recoveries.[51] Other enforcement targets procurement fraud against agencies like the General Services Administration, violations of environmental and health safety laws, and lobbying disclosure infractions seeking civil penalties.[51] Districts such as Maryland and South Carolina emphasize these suits to deter misconduct and recoup losses, often coordinating with investigative agencies for evidence.[53] [54] In housing enforcement, offices file pattern-or-practice complaints under the Fair Housing Act, as seen in a January 16, 2025, action by the Civil Rights Division alongside a U.S. Attorney's Office.[55] United States Attorneys collaborate with the Department of Justice's headquarters Civil Division for policy guidance and complex national cases, while retaining primary responsibility for district-specific litigation to address local enforcement needs efficiently.[1] This decentralized approach allows adaptation to regional priorities, such as environmental penalties in industrial areas or fraud recovery in high-volume federal program districts.[56]Oversight of Federal Investigations

United States Attorneys exercise primary oversight over federal criminal investigations within their judicial districts, serving as the chief federal prosecutors responsible for directing and coordinating the activities of investigative agencies such as the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), and Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF).[4] This authority stems from their statutory mandate under 28 U.S.C. § 547 to prosecute offenses against the United States, which encompasses supervising evidence collection, approving investigative techniques like search warrants and subpoenas, and ensuring compliance with Department of Justice (DOJ) policies and constitutional requirements.[9] In practice, U.S. Attorneys' offices review agency investigative plans, provide legal guidance to agents, and integrate findings from multi-agency operations to determine prosecutorial viability, thereby bridging law enforcement operations with courtroom strategy.[57] [4] The FBI, for instance, reports its investigative findings directly to U.S. Attorneys in the relevant districts, who assess whether sufficient probable cause exists to seek indictments or proceed to trial.[58] This oversight extends to coordinating joint task forces involving federal, state, and local entities, where U.S. Attorneys allocate resources, prioritize targets based on national and district-specific priorities (such as drug trafficking or violent crime surges), and mitigate jurisdictional overlaps to avoid duplicative efforts.[4] For example, in high-profile cases like firearms trafficking or organized crime rings, U.S. Attorneys lead interagency discussions to align investigative scopes with enforceable charges, as demonstrated in operations yielding hundreds of seizures or indictments annually across districts.[59] [60] While U.S. Attorneys maintain operational independence in directing investigations under the Attorney General's guidelines, this role is not absolute; agencies retain autonomy in initial case initiation, and disputes may escalate to DOJ headquarters for resolution, particularly in sensitive national security or cross-district matters.[58] Effective oversight hinges on robust communication protocols, with U.S. Attorneys' offices embedding Assistant U.S. Attorneys as liaisons to federal task forces, ensuring real-time legal oversight to prevent procedural errors that could jeopardize convictions.[61] This framework promotes accountability but has faced scrutiny in instances of perceived investigative overreach or policy misalignments, though statutory mechanisms prioritize prosecutorial discretion rooted in evidentiary sufficiency rather than political directives.[2]Organizational Structure

Executive Office for United States Attorneys

The Executive Office for United States Attorneys (EOUSA) serves as the primary liaison between the Department of Justice headquarters in Washington, D.C., and the 93 offices of United States Attorneys operating across the 50 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, the United States Virgin Islands, Guam, and the Northern Mariana Islands.[6] Established on April 6, 1953, through Attorney General Order No. 8-53, EOUSA was created to enhance coordination and support for these offices amid growing federal litigation demands following World War II and the expansion of federal law enforcement responsibilities.[6] Its core purpose is to supervise and assist United States Attorneys in executing Department of Justice policies uniformly, ensuring effective prosecution of federal crimes and civil enforcement actions.[34] EOUSA's functions encompass administrative oversight, performance evaluation, and operational support for the United States Attorneys' offices, which collectively handle the majority of federal criminal and civil cases.[34] It conducts regular inspections of these offices to assess compliance with departmental standards, evaluates attorneys' performance metrics such as case disposition rates and resource utilization, and implements corrective measures where deficiencies are identified.[6] Additionally, EOUSA provides technical assistance in areas like budgeting, legal training programs, and the development of uniform procedures for debt collection, criminal fine enforcement, and victim-witness support services, thereby standardizing practices across districts with varying caseloads and priorities.[6] In terms of policy implementation, EOUSA maintains and updates key departmental resources, including oversight of the Justice Manual, which outlines prosecutorial guidelines and operational protocols for federal litigators.[6] It also coordinates responses to Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) and Privacy Act requests originating from United States Attorneys' offices, processing records related to investigations, litigation, and administrative matters while ensuring adherence to statutory timelines and exemptions.[6] The office's General Counsel provides legal advice and litigation support to United States Attorneys on internal management issues, distinct from case-specific prosecutorial decisions.[62] EOUSA's organizational structure, as detailed in its official chart, includes divisions focused on evaluation, management, and support services, led by a director appointed within the Department of Justice hierarchy.[63]District-Level Operations and Staffing

Each of the 94 federal judicial districts maintains a United States Attorney's Office (USAO) responsible for representing the United States in all federal court proceedings within that district, encompassing both criminal prosecutions and civil litigation.[64] There are 93 such offices, as Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands share a single U.S. Attorney.[64] The U.S. Attorney directs operations as the district's chief federal law enforcement officer, exercising prosecutorial discretion to enforce federal statutes, defend government interests in civil suits, and pursue recovery of fines, penalties, and forfeitures.[64] These offices handle the bulk of the Department of Justice's trial-level work, coordinating with federal investigative agencies such as the FBI and DEA to initiate and litigate cases.[64] USAOs are typically structured into primary divisions for criminal and civil matters, with the criminal division—focused on indictments, trials, and appeals in federal offenses—often comprising the larger share of personnel due to higher caseload volumes.[65] Additional sections may include appellate units for handling circuit court reviews and specialized teams for areas like national security or financial fraud, depending on district priorities.[12] Day-to-day operations involve case intake from law enforcement referrals, grand jury presentations, plea negotiations, and trial preparation, all aligned with national DOJ policies while allowing local adaptation to regional threats such as drug trafficking or public corruption.[46] Staffing centers on Assistant United States Attorneys (AUSAs), career prosecutors who litigate cases under the U.S. Attorney's supervision, totaling over 6,400 nationwide as of 2023.[66] Personnel levels vary by district caseload and population; for instance, smaller districts like Montana maintain around 30 AUSAs, while high-volume offices in major metropolitan areas employ hundreds.[67] Support staff, including paralegals, victim-witness coordinators, and administrative personnel, typically matches or approaches AUSA numbers in larger offices to handle logistics, discovery, and compliance.[5] Hiring for AUSAs emphasizes experienced litigators, often with 3–8 years post-law school in clerkships or private practice, and is subject to DOJ-wide priorities such as immigration enforcement or violent crime initiatives.[65] The Executive Office for United States Attorneys (EOUSA) oversees budgeting, training, and human resources, but district staffing decisions remain under the U.S. Attorney's operational control.[64]Political Dimensions

Inherent Political Character of the Role

The position of United States Attorney is structurally political, as incumbents are appointed by the President with the advice and consent of the Senate pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 541(a), a process that enables selection of nominees typically affiliated with the appointing President's political party or ideological alignment.[3] This appointment mechanism, combined with the absence of fixed tenure protections beyond a nominal four-year term under § 541(b), positions United States Attorneys as extensions of executive power rather than insulated judicial or civil service roles, allowing presidents to install personnel who can direct federal prosecutions in alignment with administration priorities such as immigration enforcement or corporate regulatory actions. The confirmation process itself is inherently partisan, as Senate majorities often condition approval on nominees' demonstrated loyalty to the executive's law enforcement agenda, ensuring control over the application of federal statutes across 94 districts.[68] Prosecutorial discretion inherent to the role amplifies its political dimensions, as United States Attorneys exercise authority over charging decisions, resource allocation, and policy-driven initiatives like task forces on violent crime or civil rights, often guided by directives from politically appointed Department of Justice leadership including the Attorney General.[69] Empirical analysis of appointments from 1970 to 2022 reveals consistent patterns of partisan selection, with over 90% of nominees sharing the President's party affiliation, underscoring the role's function as a tool for partisan governance rather than apolitical adjudication.[70] Removal authority further embeds this politicization, as presidents routinely dismiss predecessors' appointees upon assuming office—evidenced by near-total turnover in the early months of administrations from Reagan through Biden—to realign district-level operations with current executive mandates.[70] While career prosecutors handle much day-to-day litigation, the United States Attorney's oversight role in setting district priorities and approving high-profile cases introduces avenues for political influence, as seen in variations in enforcement vigor across administrations on issues like drug policy or election integrity.[71] This structure reflects Article II's vesting of executive power in the President, prioritizing accountability to elected leadership over prosecutorial autonomy, though it has prompted debates over whether such integration compromises impartial justice.[69] Historical precedents, including patronage origins dating to the Judiciary Act of 1789, confirm the role's evolution as a politically accountable office rather than an independent one akin to Article III judges.[70]Alignment with Executive Policy Priorities

United States Attorneys, as political appointees serving at the pleasure of the President, are directed to align their offices' prosecutorial activities with the executive branch's law enforcement priorities, primarily through guidance issued by the Attorney General and Deputy Attorney General. These priorities are disseminated via departmental memoranda that specify focus areas for investigations, charging decisions, and resource allocation across the 94 U.S. Attorney districts, ensuring federal prosecutions reflect the administration's policy objectives such as border security, organized crime disruption, and targeted corporate accountability.[72][70] In the second Trump administration, this alignment was explicitly reinforced through multiple directives. On February 5, 2025, Attorney General Pam Bondi issued orders rescinding prior guidance and establishing new investigative emphases on immigration enforcement, human trafficking and smuggling, and cartel-related foreign bribery, directing U.S. Attorneys to prioritize these over previous regulatory-focused pursuits.[73][74] A subsequent March 6, 2025, memorandum from Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche outlined staffing priorities for U.S. Attorneys' offices to bolster capacities against illegal immigration, transnational criminal organizations, and related threats, mandating hiring freezes in non-priority areas to redirect resources.[72] Practical implementation is evident in district-level actions. For example, U.S. Attorney Edward R. Martin Jr. for the District of Columbia launched the "Make D.C. Safe Again" initiative in March 2025, crediting President Trump's early-term policies with contributing to a 25% reduction in violent crime that month, through intensified federal-local partnerships targeting repeat offenders and gang activity.[75] Similarly, an April 7, 2025, Deputy Attorney General memorandum titled "Ending Regulation By Prosecution" instructed U.S. Attorneys to deprioritize cases involving mere regulatory violations of digital assets while focusing on prosecutions for direct financial harms to investors and consumers, aligning with broader deregulation aims.[76] These directives illustrate a causal mechanism where executive policy cascades from the White House through DOJ leadership to U.S. Attorneys, who exercise discretion within statutory bounds but adapt to shifting national imperatives, such as heightened border enforcement under statutes like 8 U.S.C. § 1325 for improper entry. Empirical outcomes, including case initiation rates and conviction statistics reported in DOJ annual summaries, serve as metrics for this alignment, though district variations arise from local crime patterns and judicial constraints.[77][78]Major Controversies

The 2006-2007 Dismissals Under Bush Administration

In December 2006, the U.S. Department of Justice, under Attorney General Alberto Gonzales, directed the resignation of seven United States Attorneys effective at the end of January 2007, as part of a broader process that removed nine in total during 2006.[79] The affected prosecutors included David Iglesias (New Mexico), Daniel Bogden (Nevada), Paul Charlton (Arizona), John McKay (Western Washington), Carol Lam (Southern California), Margaret Chiara (Western Michigan), and Kevin Ryan (Northern California), with earlier removals of H.E. "Bud" Cummins (Eastern Arkansas) in June 2006 and Todd Graves (Eastern Missouri) in March 2006.[79] This action, orchestrated primarily by Gonzales's chief of staff Kyle Sampson, stemmed from a review process initiated as early as November 2004 following President George W. Bush's reelection, with Sampson proposing initial lists of up to 14 candidates in March 2005 and refining to nine by January 2006 based on input from DOJ officials, White House counsel, and congressional figures.[79] The stated rationale from DOJ leadership emphasized performance deficiencies and alignment with departmental priorities, such as prosecution rates in immigration and firearms cases or management evaluations via the Evaluation and Review Staff (EARS).[79] However, a joint investigation by the DOJ Office of the Inspector General and Office of Professional Responsibility, released in September 2008 after interviewing approximately 90 individuals and reviewing thousands of documents, determined that reasons varied across cases and included policy disagreements (e.g., Charlton's opposition to routine interrogation recordings and death penalty protocols), perceived mediocrity (e.g., Bogden's handling of obscenity task force assignments), and external political pressures from Republican senators and representatives (e.g., complaints from Sen. Pete Domenici and Rep. Heather Wilson about Iglesias's delays in voter fraud and corruption probes).[79] For instance, Cummins's removal facilitated the appointment of Timothy Griffin, a former Karl Rove aide, while Graves's stemmed from discord involving Sen. Kit Bond's staff; Ryan's was substantiated by EARS findings of poor morale and turnover, but others like Lam's focused on low enforcement statistics without ties to ongoing investigations such as the Duke Cunningham scandal.[79]| U.S. Attorney | District | Primary Reasons Cited in Investigation |

|---|---|---|

| Todd Graves | Eastern Missouri | Political pressure from Sen. Bond's staff over local disputes; not performance-based.[79] |

| H.E. "Bud" Cummins | Eastern Arkansas | To enable Griffin appointment; not performance-related.[79] |

| David Iglesias | New Mexico | Delays in voter fraud and corruption cases, per GOP complaints; political influence evident.[79] |

| Daniel Bogden | Nevada | Policy refusal on obscenity task force; viewed as mediocre.[79] |

| Paul Charlton | Arizona | Policy clashes on interrogations and death penalty; alleged improper senatorial contact.[79] |

| John McKay | Western Washington | Disputes over LInX data-sharing program; unsubstantiated voter fraud critiques.[79] |

| Carol Lam | Southern California | Low immigration/firearms prosecution rates; no interference in specific cases.[79] |

| Margaret Chiara | Western Michigan | Management turmoil in office.[79] |

| Kevin Ryan | Northern California | EARS-documented management failures, high turnover.[79] |