Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

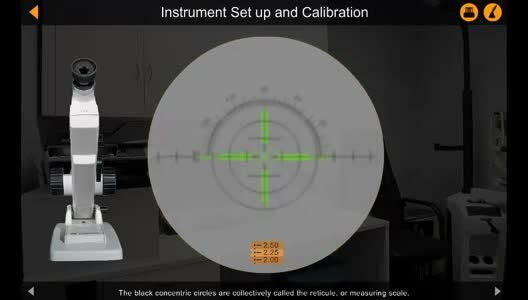

Lensmeter

View on Wikipedia

3 – Objective lens 4 – Keplerian telescope

5 – Lens holder 6 – Unknown lens

7 – Standard lens 8 – Illuminated target

9 – Light source 10 – Collimator

11 – Angle adjustment lever

12 – Power drum (+20 and -20 Diopters)

13 – Prism scale knob

A lensmeter or lensometer (sometimes even known as focimeter or vertometer),[1][2] is an optical instrument used in ophthalmology. It is mainly used by optometrists and opticians to measure the back or front vertex power of a spectacle lens and verify the correct prescription in a pair of eyeglasses, to properly orient and mark uncut lenses, and to confirm the correct mounting of lenses in spectacle frames. Lensmeters can also verify the power of contact lenses, if a special lens support is used.

The parameters appraised by a lensmeter are the values specified by an ophthalmologist or optometrist on the patient's prescription: sphere, cylinder, axis, add, and in some cases, prism. The lensmeter is also used to check the accuracy of progressive lenses, and is often capable of marking the lens center and various other measurements critical to proper performance of the lens. It may also be used prior to an eye examination to obtain the last prescription the patient was given, in order to expedite the subsequent examination.

History

[edit]In 1848, Antoine Claudet produced the photographometer, an instrument designed to measure the intensity of photogenic rays; and in 1849 he brought out the focimeter, for securing a perfect focus in photographic portraiture. [3] In 1876, Hermann Snellen introduced a phakometer which was a similar set up to an optical bench which could measure the power and find the optical centre of a convex lens. Troppman went a step further in 1912, introducing the first direct measuring instrument.

In 1922, a patent was filed for the first projection lensmeter, which has a similar system to the standard lensmeter pictured above, but projects the measuring target onto a screen eliminating the need for correction of the observer's refractive error in the instrument itself and reducing the requirement to peer down a small telescope into the instrument. Despite these advantages the above design is still predominant in the optical world.[4]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Vertometer. (n.d.)". Millodot: Dictionary of Optometry & Visual Science, 7th edition. 2009. Retrieved 2015-01-04.

- ^ "Ophthalmology Glossary on Carl Zeiss Vision GmbH website". Archived from the original on 12 May 2008.

- ^ Solbert, Oscar N.; Newhall, Beaumont; Card, James G., eds. (February 1952). "The Focimeter" (PDF). Image. 1 (2). Rochester, N.Y.: International Museum of Photography at George Eastman House Inc.: 1–2. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 12, 2013. Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- ^ "Focimeters". Archived from the original on 2008-05-12. Retrieved 2010-01-30. accessed 20 Jan 2009

External links

[edit]- Lensometry basics Archived 2010-11-25 at the Wayback Machine

- The lensmeter