Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

PRISM

View on Wikipedia

National Security Agency surveillance |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Global surveillance |

|---|

| Disclosures |

| Systems |

| Selected agencies |

| Places |

| Laws |

| Proposed changes |

| Concepts |

| Related topics |

PRISM is a code name for a program under which the United States National Security Agency (NSA) collects internet communications from various U.S. internet companies.[1][2][3] The program is also known by the SIGAD US-984XN.[4][5] PRISM collects stored internet communications based on demands made to internet companies such as Google LLC and Apple under Section 702 of the FISA Amendments Act of 2008 to turn over any data that match court-approved search terms.[6] Among other things, the NSA can use these PRISM requests to target communications that were encrypted when they traveled across the internet backbone, to focus on stored data that telecommunication filtering systems discarded earlier,[7][8] and to get data that is easier to handle.[9]

PRISM began in 2007 in the wake of the passage of the Protect America Act under the Bush Administration.[10][11] The program is operated under the supervision of the U.S. Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISA Court, or FISC) pursuant to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA).[12] Its existence was leaked six years later by NSA contractor Edward Snowden, who warned that the extent of mass data collection was far greater than the public knew and included what he characterized as "dangerous" and "criminal" activities.[13] The disclosures were published by The Guardian and The Washington Post on June 6, 2013. Subsequent documents have demonstrated a financial arrangement between the NSA's Special Source Operations (SSO) division and PRISM partners in the millions of dollars.[14]

Documents indicate that PRISM is "the number one source of raw intelligence used for NSA analytic reports", and it accounts for 91% of the NSA's internet traffic acquired under FISA section 702 authority."[15][16] The leaked information came after the revelation that the FISA Court had been ordering a subsidiary of telecommunications company Verizon Communications to turn over logs tracking all of its customers' telephone calls to the NSA.[17][18]

U.S. government officials have disputed criticisms of PRISM in the Guardian and Washington Post articles and have defended the program, asserting that it cannot be used on domestic targets without a warrant. They additionally claim that the program has helped to prevent acts of terrorism, and that it receives independent oversight from the federal government's executive, judicial and legislative branches.[19][20] On June 19, 2013, U.S. President Barack Obama, during a visit to Germany, stated that the NSA's data gathering practices constitute "a circumscribed, narrow system directed at us being able to protect our people."[21]

Media disclosure of PRISM

[edit]Edward Snowden publicly revealed the existence of PRISM through a series of classified documents leaked to journalists of The Washington Post and The Guardian while he was an NSA contractor at the time, thus fleeing to Hong Kong.[1][2] The leaked documents included 41 PowerPoint slides, four of which were published in news articles.[1][2]

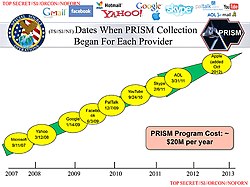

The documents identified several technology companies as participants in the PRISM program, including Microsoft in 2007, Yahoo! in 2008, Google in 2009, Facebook in 2009, Paltalk in 2009, YouTube in 2010, AOL in 2011, Skype in 2011 and Apple in 2012.[22] The speaker's notes in the briefing document reviewed by The Washington Post indicated that "98 percent of PRISM production is based on Yahoo, Google, and Microsoft".[1]

The slide presentation stated that much of the world's electronic communications pass through the U.S., because electronic communications data tend to follow the least expensive route rather than the most physically direct route, and the bulk of the world's internet infrastructure is based in the United States.[15] The presentation noted that these facts provide United States intelligence analysts with opportunities for intercepting the communications of foreign targets as their electronic data pass into or through the United States.[2][15]

Snowden's subsequent disclosures included statements that government agencies such as the United Kingdom's GCHQ also undertook mass interception and tracking of internet and communications data[23] – described by Germany as "nightmarish" if true[24] – allegations that the NSA engaged in "dangerous" and "criminal" activity by "hacking" civilian infrastructure networks in other countries such as "universities, hospitals, and private businesses",[13] and alleged that compliance offered only very limited restrictive effect on mass data collection practices (including of Americans) since restrictions "are policy-based, not technically based, and can change at any time", adding that "Additionally, audits are cursory, incomplete, and easily fooled by fake justifications",[13] with numerous self-granted exceptions, and that NSA policies encourage staff to assume the benefit of the doubt in cases of uncertainty.[25][26][27]

The slides

[edit]Below are a number of slides released by Edward Snowden showing the operation and processes behind the PRISM program. The "FAA" referred to is Section 702 of the FISA Amendments Act ("FAA"), and not the widely known Federal Aviation Administration (FAA).[28]

-

Introduction slide

-

Slide showing that much of the world's communications flow through the U.S.

-

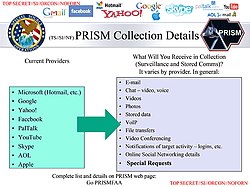

Details of information collected via PRISM

-

Slide listing companies and the date that PRISM collection began

-

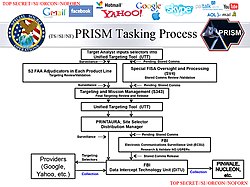

Slide showing PRISM's tasking process

-

Slide showing the PRISM collection dataflow

-

Slide showing PRISM case numbers

-

Slide showing the REPRISMFISA Web app

-

Slide showing some PRISM targets.

-

Slide fragment mentioning "upstream collection", FAA702, EO 12333, and references yahoo.com explicitly in the text

-

FAA702 Operations, and map

-

FAA702 Operations, and map. The subheader reads "Collection only possible under FAA702 Authority". FAIRVIEW is in the center box.

-

FAA702 Operations, and map. The subheader reads "Collection only possible under FAA702 Authority". STORMBREW is in the center box.

-

Tasking, Points to Remember. Transcript of body: "Whenever your targets meet FAA criteria, you should consider asking to FAA. Emergency tasking processes exist for [imminent /immediate ] threat to life situations and targets can be placed on [illegible] within hours (surveillance and stored comms). Get to know your Product line FAA adjudicators and FAA leads."

The French newspaper Le Monde disclosed new PRISM slides (see pages 4, 7 and 8) coming from the "PRISM/US-984XN Overview" presentation on October 21, 2013.[29] The British newspaper The Guardian disclosed new PRISM slides (see pages 3 and 6) in November 2013 which on the one hand compares PRISM with the Upstream program, and on the other hand deals with collaboration between the NSA's Threat Operations Center and the FBI.[30]

The program

[edit]

PRISM is a program from the Special Source Operations (SSO) division of the NSA, which in the tradition of NSA's intelligence alliances, cooperates with as many as 100 trusted U.S. companies since the 1970s.[1] A prior program, the Terrorist Surveillance Program,[31][32] was implemented in the wake of the September 11 attacks under the George W. Bush Administration but was widely criticized and challenged as illegal, because it did not include warrants obtained from the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court.[32][33][34][35][36] PRISM was authorized by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court.[15]

PRISM was enabled under President Bush by the Protect America Act of 2007 and by the FISA Amendments Act of 2008, which immunizes private companies from legal action when they cooperate with U.S. government agencies in intelligence collection. In 2012 the act was renewed by Congress under President Obama for an additional five years, through December 2017.[2][37][38] According to The Register, the FISA Amendments Act of 2008 "specifically authorizes intelligence agencies to monitor the phone, email, and other communications of U.S. citizens for up to a week without obtaining a warrant" when one of the parties is outside the U.S.[37]

The most detailed description of the PRISM program can be found in a report about NSA's collection efforts under Section 702 FAA, that was released by the Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board (PCLOB) on July 2, 2014.[39]

According to this report, PRISM is only used to collect internet communications, not telephone conversations. These internet communications are not collected in bulk, but in a targeted way: only communications that are to or from specific selectors, like e-mail addresses, can be gathered. Under PRISM, there is no collection based on keywords or names.[39]

The actual collection process is done by the Data Intercept Technology Unit (DITU) of the FBI, which on behalf of the NSA sends the selectors to the U.S. internet service providers, which were previously served with a Section 702 Directive. Under this directive, the provider is legally obliged to hand over (to DITU) all communications to or from the selectors provided by the government.[39] DITU then sends these communications to NSA, where they are stored in various databases, depending on their type.

Data, both content and metadata, that already have been collected under the PRISM program, may be searched for both US and non-US person identifiers. These kinds of queries became known as "back-door searches" and are conducted by NSA, FBI and CIA.[40] Each of these agencies has slightly different protocols and safeguards to protect searches with a US person identifier.[39]

Extent of the program

[edit]Internal NSA presentation slides included in the various media disclosures show that the NSA could unilaterally access data and perform "extensive, in-depth surveillance on live communications and stored information" with examples including email, video and voice chat, videos, photos, voice-over-IP chats (such as Skype), file transfers, and social networking details.[2] Snowden summarized that "in general, the reality is this: if an NSA, FBI, CIA, DIA, etc. analyst has access to query raw SIGINT [signals intelligence] databases, they can enter and get results for anything they want."[13]

According to The Washington Post, the intelligence analysts search PRISM data using terms intended to identify suspicious communications of targets whom the analysts suspect with at least 51 percent confidence to not be U.S. citizens, but in the process, communication data of some U.S. citizens are also collected unintentionally.[1] Training materials for analysts tell them that while they should periodically report such accidental collection of non-foreign U.S. data, "it's nothing to worry about."[1][41]

According to The Guardian, NSA had access to chats and emails on Hotmail.com and Skype because Microsoft had "developed a surveillance capability to deal" with the interception of chats, and "for Prism collection against Microsoft email services will be unaffected because Prism collects this data prior to encryption."[42][43]

Also according to The Guardian's Glenn Greenwald even low-level NSA analysts are allowed to search and listen to the communications of Americans and other people without court approval and supervision. Greenwald said low level Analysts can, via systems like PRISM, "listen to whatever emails they want, whatever telephone calls, browsing histories, Microsoft Word documents.[31] And it's all done with no need to go to a court, with no need to even get supervisor approval on the part of the analyst."[44]

He added that the NSA databank, with its years of collected communications, allows analysts to search that database and listen "to the calls or read the emails of everything that the NSA has stored, or look at the browsing histories or Google search terms that you've entered, and it also alerts them to any further activity that people connected to that email address or that IP address do in the future."[44] Greenwald was referring in the context of the foregoing quotes to the NSA program XKeyscore.[45]

PRISM overview

[edit]| Designation | Legal AuthoritySee Note | Key Targets | Type of Information collected | Associated Databases | Associated Software |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US-984XN | Section 702 of the FISA Amendments Act (FAA) | Known Targets include[46]

|

The exact type of data varies by provider:

|

Known:

|

Known: |

Responses to disclosures

[edit]United States government

[edit]Executive branch life

[edit]Shortly after publication of the reports by The Guardian and The Washington Post, the United States Director of National Intelligence, James Clapper, on June 7, 2013, released a statement confirming that for nearly six years the government of the United States had been using large internet services companies such as Facebook to collect information on foreigners outside the United States as a defense against national security threats.[17] The statement read in part, "The Guardian and The Washington Post articles refer to collection of communications pursuant to Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act. They contain numerous inaccuracies."[47] He went on to say, "Section 702 is a provision of FISA that is designed to facilitate the acquisition of foreign intelligence information concerning non-U.S. persons located outside the United States. It cannot be used to intentionally target any U.S. citizen, any other U.S. person, or anyone located within the United States."[47] Clapper concluded his statement by stating, "The unauthorized disclosure of information about this important and entirely legal program is reprehensible and risks important protections for the security of Americans."[47] On March 12, 2013, Clapper had told the United States Senate Select Committee on Intelligence that the NSA does "not wittingly" collect any type of data on millions or hundreds of millions of Americans.[48] Clapper later admitted the statement he made on March 12, 2013, was a lie,[49] or in his words "I responded in what I thought was the most truthful, or least untruthful manner by saying no."[50]

On June 7, 2013, U.S. President Barack Obama, referring to the PRISM program[51] and the NSA's telephone calls logging program, said, "What you've got is two programs that were originally authorized by Congress, have been repeatedly authorized by Congress. Bipartisan majorities have approved them. Congress is continually briefed on how these are conducted. There are a whole range of safeguards involved. And federal judges are overseeing the entire program throughout."[52] He also said, "You can't have 100 percent security and then also have 100 percent privacy and zero inconvenience. You know, we're going to have to make some choices as a society."[52] Obama also said that government collection of data was needed in order to catch terrorists.[53] In separate statements, senior Obama administration officials (not mentioned by name in source) said that Congress had been briefed 13 times on the programs since 2009.[54]

On June 8, 2013, Director of National Intelligence Clapper made an additional public statement about PRISM and released a fact sheet providing further information about the program, which he described as "an internal government computer system used to facilitate the government's statutorily authorized collection of foreign intelligence information from electronic communication service providers under court supervision, as authorized by Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) (50 U.S.C. § 1881a)."[55][56] The fact sheet stated that "the surveillance activities published in The Guardian and the Washington Post are lawful and conducted under authorities widely known and discussed, and fully debated and authorized by Congress."[55] The fact sheet also stated that "the United States Government does not unilaterally obtain information from the servers of U.S. electronic communication service providers. All such information is obtained with FISA Court approval and with the knowledge of the provider based on a written directive from the Attorney General and the Director of National Intelligence." It said that the attorney general provides FISA Court rulings and semi-annual reports about PRISM activities to Congress, "provid[ing] an unprecedented degree of accountability and transparency."[55] Democratic senators Udall and Wyden, who serve on the U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, subsequently criticized the fact sheet as being inaccurate.[clarification needed] NSA Director General Keith Alexander acknowledged the errors, stating that the fact sheet "could have more precisely described" the requirements governing the collection of e-mail and other internet content from US companies. The fact sheet was withdrawn from the NSA's website around June 26.[57]

In a closed-doors Senate hearing around June 11, FBI Director Robert Mueller said that Snowden's leaks had caused "significant harm to our nation and to our safety."[58] In the same Senate hearing, NSA Director Alexander defended the program.[further explanation needed] Alexander's defense was immediately criticized by Senators Udall and Wyden, who said they saw no evidence that the NSA programs had produced "uniquely valuable intelligence." In a joint statement, they wrote, "Gen Alexander's testimony yesterday suggested that the NSA's bulk phone records collection program helped thwart 'dozens' of terrorist attacks, but all of the plots that he mentioned appear to have been identified using other collection methods."[58][59]

On June 18, NSA Director Alexander said in an open hearing before the House Intelligence Committee of Congress that communications surveillance had helped prevent more than 50 potential terrorist attacks worldwide (at least 10 of them involving terrorism suspects or targets in the United States) between 2001 and 2013, and that the PRISM web traffic surveillance program contributed in over 90 percent of those cases.[60][61][62] According to court records, one example Alexander gave regarding a thwarted attack by al Qaeda on the New York Stock Exchange was not in fact foiled by surveillance.[63] Several senators wrote Director of National Intelligence Clapper asking him to provide other examples.[64]

U.S. intelligence officials, speaking on condition of anonymity, told various news outlets that by June 24 they were already seeing what they said was evidence that suspected terrorists had begun changing their communication practices in order to evade detection by the surveillance tools disclosed by Snowden.[65][66]

Legislative branch

[edit]In contrast to their swift and forceful reactions the previous day to allegations that the government had been conducting surveillance of United States citizens' telephone records, Congressional leaders initially had little to say about the PRISM program the day after leaked information about the program was published. Several lawmakers declined to discuss PRISM, citing its top-secret classification,[67] and others said that they had not been aware of the program.[68] After statements had been released by the president and the Director of National Intelligence, some lawmakers began to comment:

Senator John McCain (R-AZ)

- June 9, 2013, "We passed the Patriot Act. We passed specific provisions of the act that allowed for this program to take place, to be enacted in operation."[69]

Senator Dianne Feinstein (D-CA), chair of the Senate Intelligence Committee

- June 9, "These programs are within the law," "part of our obligation is keeping Americans safe," "Human intelligence isn't going to do it."[70]

- June 9, "Here's the rub: the instances where this has produced good—has disrupted plots, prevented terrorist attacks, is all classified, that's what's so hard about this."[71]

- June 11, "It went fine. ... We asked him (Keith Alexander) to declassify things because it would be helpful (for people and lawmakers to better understand the intelligence programs). ... I've just got to see if the information gets declassified. I'm sure people will find it very interesting."[72]

Senator Rand Paul (R-KY)

- June 9, "I'm going to be seeing if I can challenge this at the Supreme Court level. I'm going to be asking the internet providers and all of the phone companies: ask your customers to join me in a class-action lawsuit."[69]

Senator Susan Collins (R-ME), member of Senate Intelligence Committee and past member of Homeland Security Committee

- June 11, "I had, along with Joe Lieberman, a monthly threat briefing, but I did not have access to this highly compartmentalized information" and "How can you ask when you don't know the program exists?"[73]

Representative Jim Sensenbrenner (R-WI), principal sponsor of the Patriot Act

- June 9, "This is well beyond what the Patriot Act allows."[74] "President Obama's claim that 'this is the most transparent administration in history' has once again proven false. In fact, it appears that no administration has ever peered more closely or intimately into the lives of innocent Americans."[74]

Representative Mike Rogers (R-MI), a chairman of the Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence.

- June 9, "One of the things that we're charged with is keeping America safe and keeping our civil liberties and privacy intact. I think we have done both in this particular case."[70]

- June 9, "Within the last few years this program was used to stop a program, excuse me, to stop a terrorist attack in the United States, we know that. It's, it's, it's important, it fills in a little seam that we have and it's used to make sure that there is not an international nexus to any terrorism event that they may believe is ongoing in the United States. So in that regard it is a very valuable thing."[75]

Senator Mark Udall (D-CO)

- June 9, "I don't think the American public knows the extent or knew the extent to which they were being surveilled and their data was being collected. ... I think we ought to reopen the Patriot Act and put some limits on the amount of data that the National Security (Agency) is collecting. ... It ought to remain sacred, and there's got to be a balance here. That is what I'm aiming for. Let's have the debate, let's be transparent, let's open this up."[70]

Representative Todd Rokita (R-IN)

- June 10, "We have no idea when they [Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court] meet, we have no idea what their judgments are."[76]

Representative Luis Gutierrez (D-IL)

- June 9, "We will be receiving secret briefings and we will be asking, I know I'm going to be asking to get more information. I want to make sure that what they're doing is harvesting information that is necessary to keep us safe and not simply going into everybody's private telephone conversations and Facebook and communications. I mean one of the, you know, the terrorists win when you debilitate freedom of expression and privacy."[75]

Senator Ron Wyden (D-OR)

- July 11, "I have a feeling that the administration is getting concerned about the bulk phone records collection, and that they are thinking about whether to move administratively to stop it. I think we are making a comeback".[77]

Following these statements some lawmakers from both parties warned national security officials during a hearing before the House Judiciary Committee that they must change their use of sweeping National Security Agency surveillance programs or face losing the provisions of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act that have allowed for the agency's mass collection of telephone metadata.[78] "Section 215 expires at the end of 2015, and unless you realize you've got a problem, that is not going to be renewed," Rep. Jim Sensenbrenner, R-Wis., author of the USA Patriot Act, threatened during the hearing.[78] "It's got to be changed, and you've got to change how you operate section 215. Otherwise, in two and a half years, you're not going to have it anymore."[78]

Judicial branch

[edit]Leaks of classified documents pointed to the role of a special court in enabling the government's secret surveillance programs, but members of the court maintained they were not collaborating with the executive branch.[79] The New York Times, however, reported in July 2013 that in "more than a dozen classified rulings, the nation's surveillance court has created a secret body of law giving the National Security Agency the power to amass vast collections of data on Americans while pursuing not only terrorism suspects, but also people possibly involved in nuclear proliferation, espionage and cyberattacks."[80] After Members of the U.S. Congress pressed the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court to release declassified versions of its secret ruling, the court dismissed those requests arguing that the decisions can't be declassified because they contain classified information.[81] Reggie Walton, the current FISA presiding judge, said in a statement: "The perception that the court is a rubber stamp is absolutely false. There is a rigorous review process of applications submitted by the executive branch, spearheaded initially by five judicial branch lawyers who are national security experts, and then by the judges, to ensure that the court's authorizations comport with what the applicable statutes authorize."[82] The accusation of being a "rubber stamp" was further rejected by Walton who wrote in a letter to Senator Patrick J. Leahy: "The annual statistics provided to Congress by the Attorney General ...—frequently cited to in press reports as a suggestion that the Court's approval rate of application is over 99%—reflect only the number of final applications submitted to and acted on by the Court. These statistics do not reflect the fact that many applications are altered to prior or final submission or even withheld from final submission entirely, often after an indication that a judge would not approve them."[83]

The U.S. military

[edit]The U.S. military has acknowledged blocking access to parts of The Guardian website for thousands of defense personnel across the country,[84] and blocking the entire Guardian website for personnel stationed throughout Afghanistan, the Middle East, and South Asia.[85] A spokesman said the military was filtering out reports and content relating to government surveillance programs to preserve "network hygiene" and prevent any classified material from appearing on unclassified parts of its computer systems.[84] Access to the Washington Post, which also published information on classified NSA surveillance programs disclosed by Edward Snowden, had not been blocked at the time the blocking of access to The Guardian was reported.[85]

Responses and involvement of other countries

[edit]Austria

[edit]The former head of the Austrian Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution and Counterterrorism, Gert-René Polli, stated he knew the PRISM program under a different name and stated that surveillance activities had occurred in Austria as well. Polli had publicly stated in 2009 that he had received requests from US intelligence agencies to do things that would be in violation of Austrian law, which Polli refused to allow.[86][87]

Australia

[edit]The Australian government has said it will investigate the impact of the PRISM program and the use of the Pine Gap surveillance facility on the privacy of Australian citizens.[88] Australia's former foreign minister Bob Carr said that Australians should not be concerned about PRISM but that cybersecurity is high on the government's list of concerns.[89] The Australian Foreign Minister Julie Bishop stated that the acts of Edward Snowden were treachery and offered a staunch defence of her nation's intelligence co-operation with the United States.[90]

Brazil

[edit]Brazil's president at the time, Dilma Rousseff, responded to Snowden's reports that the NSA spied on her phone calls and emails by cancelling a planned October 2013 state visit to the United States, demanding an official apology, which by October 20, 2013, hadn't come.[91] Also, Rousseff classified the spying as unacceptable between more harsh words in a speech before the UN General Assembly on September 24, 2013.[92] As a result, Boeing lost out on a US$4.5 billion contract for fighter jets to Sweden's Saab Group.[93]

Canada

[edit]

Canada's national cryptologic agency, the Communications Security Establishment (CSE), said that commenting on PRISM "would undermine CSE's ability to carry out its mandate." Privacy Commissioner Jennifer Stoddart lamented Canada's standards when it comes to protecting personal online privacy stating "We have fallen too far behind" in her report. "While other nations' data protection authorities have the legal power to make binding orders, levy hefty fines and take meaningful action in the event of serious data breaches, we are restricted to a 'soft' approach: persuasion, encouragement and, at the most, the potential to publish the names of transgressors in the public interest." And, "when push comes to shove," Stoddart wrote, "short of a costly and time-consuming court battle, we have no power to enforce our recommendations."[94][95]

European Union

[edit]On 20 October 2013 a committee at the European Parliament backed a measure that, if it is enacted, would require American companies to seek clearance from European officials before complying with United States warrants seeking private data. The legislation has been under consideration for two years. The vote is part of efforts in Europe to shield citizens from online surveillance in the wake of revelations about a far-reaching spying program by the U.S. National Security Agency.[96] Germany and France have also had ongoing mutual talks about how they can keep European email traffic from going across American servers.[97]

France

[edit]On October 21, 2013, the French Foreign Minister, Laurent Fabius, summoned the U.S. Ambassador, Charles Rivkin, to the Quai d'Orsay in Paris to protest large-scale spying on French citizens by the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA). Paris prosecutors had opened preliminary inquiries into the NSA program in July, but Fabius said, "... obviously we need to go further" and "we must quickly assure that these practices aren't repeated."[98]

Germany

[edit]Germany did not receive any raw PRISM data, according to a Reuters report.[99] German Chancellor Angela Merkel said that "the internet is new to all of us" to explain the nature of the program; Matthew Schofield of McClatchy Washington Bureau said, "She was roundly mocked for that statement."[100] Gert-René Polli, a former Austrian counter-terrorism official, said in 2013 that it is "absurd and unnatural" for the German authorities to pretend not to have known anything.[86][87] The German Army was using PRISM to support its operations in Afghanistan as early as 2011.[101]

In October 2013, it was reported that the NSA monitored Merkel's cell phone.[102] The United States denied the report, but following the allegations, Merkel called President Obama and told him that spying on friends was "never acceptable, no matter in what situation."[103]

Israel

[edit]Israeli newspaper Calcalist discussed[104] the Business Insider article[105] about the possible involvement of technologies from two secretive Israeli companies in the PRISM program—Verint Systems and Narus.

Mexico

[edit]After finding out about the PRISM program, the Mexican Government has started constructing its own spying program to spy on its own citizens. According to Jenaro Villamil, a writer from Proceso, CISEN, Mexico's intelligence agency has started to work with IBM and Hewlett Packard to develop its own data gathering software. "Facebook, Twitter, Emails and other social network sites are going to be priority."[106]

New Zealand

[edit]In New Zealand, University of Otago information science Associate Professor Hank Wolfe said that "under what was unofficially known as the Five Eyes Alliance, New Zealand and other governments, including the United States, Australia, Canada, and Britain, dealt with internal spying by saying they didn't do it. But they have all the partners doing it for them and then they share all the information."[107]

Edward Snowden, in a live streamed Google Hangout to Kim Dotcom and Julian Assange, alleged that he had received intelligence from New Zealand, and the NSA has listening posts in New Zealand.[108]

Spain

[edit]At a meeting of European Union leaders held the week of 21 October 2013, Mariano Rajoy, Spain's prime minister, said that "spying activities aren't proper among partner countries and allies". On 28 October 2013 the Spanish government summoned the American ambassador, James Costos, to address allegations that the U.S. had collected data on 60 million telephone calls in Spain. Separately, Íñigo Méndez de Vigo, a Spanish secretary of state, referred to the need to maintain "a necessary balance" between security and privacy concerns, but said that the recent allegations of spying, "if proven to be true, are improper and unacceptable between partners and friendly countries".[109]

United Kingdom

[edit]In the United Kingdom, the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), which also has its own surveillance program, Tempora, had access to the PRISM program on or before June 2010 and wrote 197 reports with it in 2012 alone. The Intelligence and Security Committee of the UK Parliament reviewed the reports GCHQ produced on the basis of intelligence sought from the US. They found in each case a warrant for interception was in place in accordance with the legal safeguards contained in UK law.[110]

In August 2013, The Guardian newspaper's offices were visited by technicians from GCHQ, who ordered and supervised the destruction of the hard drives containing information acquired from Snowden.[111]

Companies

[edit]The original Washington Post and Guardian articles reporting on PRISM noted that one of the leaked briefing documents said PRISM involves collection of data "directly from the servers" of several major internet services providers.[1][2]

Initial public statements

[edit]Corporate executives of several companies identified in the leaked documents told The Guardian that they had no knowledge of the PRISM program in particular and also denied making information available to the government on the scale alleged by news reports.[2][112] Statements of several of the companies named in the leaked documents were reported by TechCrunch and The Washington Post as follows:[113][114]

- Microsoft: "We provide customer data only when we receive a legally binding order or subpoena to do so, and never on a voluntary basis. In addition we only ever comply with orders for requests about specific accounts or identifiers. If the government has a broader voluntary national security program to gather customer data, we don't participate in it."[113][115]

- Yahoo!: "Yahoo! takes users' privacy very seriously. We do not provide the government with direct access to our servers, systems, or network."[113] "Of the hundreds of millions of users we serve, an infinitesimal percentage will ever be the subject of a government data collection directive."[114]

- Facebook: "We do not provide any government organization with direct access to Facebook servers. When Facebook is asked for data or information about specific individuals, we carefully scrutinize any such request for compliance with all applicable laws, and provide information only to the extent required by law."[113]

- Google: "Google cares deeply about the security of our users' data. We disclose user data to government in accordance with the law, and we review all such requests carefully. From time to time, people allege that we have created a government 'back door' into our systems, but Google does not have a backdoor for the government to access private user data."[113] "[A]ny suggestion that Google is disclosing information about our users' internet activity on such a scale is completely false."[114]

- Apple: "We have never heard of PRISM"[116] "We do not provide any government agency with direct access to our servers, and any government agency requesting customer data must get a court order."[116]

- Dropbox: "We've seen reports that Dropbox might be asked to participate in a government program called PRISM. We are not part of any such program and remain committed to protecting our users' privacy."[113]

In response to the technology companies' confirmation of the NSA being able to directly access the companies' servers, The New York Times reported that sources had stated the NSA was gathering the surveillance data from the companies using other technical means in response to court orders for specific sets of data.[17] The Washington Post suggested, "It is possible that the conflict between the PRISM slides and the company spokesmen is the result of imprecision on the part of the NSA author. In another classified report obtained by The Post, the arrangement is described as allowing 'collection managers [to send] content tasking instructions directly to equipment installed at company-controlled locations,' rather than directly to company servers."[1] "[I]n context, 'direct' is more likely to mean that the NSA is receiving data sent to them deliberately by the tech companies, as opposed to intercepting communications as they're transmitted to some other destination.[114]

"If these companies received an order under the FISA amendments act, they are forbidden by law from disclosing having received the order and disclosing any information about the order at all," Mark Rumold, staff attorney at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, told ABC News.[117]

On May 28, 2013, Google was ordered by United States District Court Judge Susan Illston to comply with a National Security Letter issued by the FBI to provide user data without a warrant.[118] Kurt Opsahl, a senior staff attorney at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, in an interview with VentureBeat said, "I certainly appreciate that Google put out a transparency report, but it appears that the transparency didn't include this. I wouldn't be surprised if they were subject to a gag order."[119]

The New York Times reported on June 7, 2013, that "Twitter declined to make it easier for the government. But other companies were more compliant, according to people briefed on the negotiations."[120] The other companies held discussions with national security personnel on how to make data available more efficiently and securely.[120] In some cases, these companies made modifications to their systems in support of the intelligence collection effort.[120] The dialogues have continued in recent months, as General Martin Dempsey, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, has met with executives including those at Facebook, Microsoft, Google and Intel.[120] These details on the discussions provide insight into the disparity between initial descriptions of the government program including a training slide which states, "Collection directly from the servers"[121] and the companies' denials.[120]

While providing data in response to a legitimate FISA request approved by the FISA Court is a legal requirement, modifying systems to make it easier for the government to collect the data is not. This is why Twitter could legally decline to provide an enhanced mechanism for data transmission.[120] Other than Twitter, the companies were effectively asked to construct a locked mailbox and provide the key to the government, people briefed on the negotiations said.[120] Facebook, for instance, built such a system for requesting and sharing the information.[120] Google does not provide a lockbox system, but instead transmits required data by hand delivery or ssh.[122]

Post-PRISM transparency reports

[edit]In response to the publicity surrounding media reports of data-sharing, several companies requested permission to reveal more public information about the nature and scope of information provided in response to National Security requests.

On June 14, 2013, Facebook reported that the U.S. government had authorized the communication of "about these numbers in aggregate, and as a range." In a press release posted to its web site, the company reported, "For the six months ending December 31, 2012, the total number of user-data requests Facebook received from any and all government entities in the U.S. (including local, state, and federal, and including criminal and national security-related requests) – was between 9,000 and 10,000." The company further reported that the requests impacted "between 18,000 and 19,000" user accounts, a "tiny fraction of one percent" of more than 1.1 billion active user accounts.[123]

That same day, Microsoft reported that for the same period, it received "between 6,000 and 7,000 criminal and national security warrants, subpoenas and orders affecting between 31,000 and 32,000 consumer accounts from U.S. governmental entities (including local, state and federal)" which impacted "a tiny fraction of Microsoft's global customer base."[124]

Google issued a statement criticizing the requirement that data be reported in aggregated form, stating that lumping national security requests with criminal request data would be "a step backwards" from its previous, more detailed practices on its website's transparency report. The company said that it would continue to seek government permission to publish the number and extent of FISA requests.[125]

Cisco Systems saw a huge drop in export sales because of fears that the National Security Agency could be using backdoors in its products.[126]

On September 12, 2014, Yahoo! reported the U.S. Government threatened the imposition of $250,000 in fines per day if Yahoo didn't hand over user data as part of the NSA's PRISM program.[127] It is not known if other companies were threatened or fined for not providing data in response to a legitimate FISA requests.

Public and media response

[edit]Domestic

[edit]

The New York Times editorial board charged that the Obama administration "has now lost all credibility on this issue,"[128] and lamented that "for years, members of Congress ignored evidence that domestic intelligence-gathering had grown beyond their control, and, even now, few seem disturbed to learn that every detail about the public's calling and texting habits now reside in a N.S.A. database."[129] It wrote with respect to the FISA-Court in context of PRISM that it is "a perversion of the American justice system" when "judicial secrecy is coupled with a one-sided presentation of the issues."[130] According to the New York Times, "the result is a court whose reach is expanding far beyond its original mandate and without any substantive check."[130]

James Robertson, a former federal district judge based in Washington who served on the secret Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act court for three years between 2002 and 2005 and who ruled against the Bush administration in the landmark Hamdan v. Rumsfeld case, said FISA court is independent but flawed because only the government's side is represented effectively in its deliberations. "Anyone who has been a judge will tell you a judge needs to hear both sides of a case," said James Robertson.[131] Without this judges do not benefit from adversarial debate. He suggested creating an advocate with security clearance who would argue against government filings.[132] Robertson questioned whether the secret FISA court should provide overall legal approval for the surveillance programs, saying the court "has turned into something like an administrative agency." Under the changes brought by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 Amendments Act of 2008, which expanded the US government's authority by forcing the court to approve entire surveillance systems and not just surveillance warrants as it previously handled, "the court is now approving programmatic surveillance. I don't think that is a judicial function."[131] Robertson also said he was "frankly stunned" by the New York Times report[80] that FISA court rulings had created a new body of law broadening the ability of the NSA to use its surveillance programs to target not only terrorists but suspects in cases involving espionage, cyberattacks and weapons of mass destruction.[131]

Former CIA analyst Valerie Plame Wilson and former U.S. diplomat Joseph Wilson, writing in an op-ed article published in The Guardian, said that "Prism and other NSA data-mining programs might indeed be very effective in hunting and capturing actual terrorists, but we don't have enough information as a society to make that decision."[133]

The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), an international non-profit digital-rights group based in the U.S., is hosting a tool, by which an American resident can write to their government representatives regarding their opposition to mass spying.[134]

The Obama administration's argument that NSA surveillance programs such as PRISM and Boundless Informant had been necessary to prevent acts of terrorism was challenged by several parties. Ed Pilkington and Nicholas Watt of The Guardian said of the case of Najibullah Zazi, who had planned to bomb the New York City Subway, that interviews with involved parties and U.S. and British court documents indicated that the investigation into the case had actually been initiated in response to "conventional" surveillance methods such as "old-fashioned tip-offs" of the British intelligence services, rather than to leads produced by NSA surveillance.[135] Michael Daly of The Daily Beast stated that even though Tamerlan Tsarnaev, who conducted the Boston Marathon bombing with his brother Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, had visited the Al Qaeda-affiliated Inspire magazine website, and even though Russian intelligence officials had raised concerns with U.S. intelligence officials about Tamerlan Tsarnaev, PRISM did not prevent him from carrying out the Boston attacks. Daly observed that, "The problem is not just what the National Security Agency is gathering at the risk of our privacy but what it is apparently unable to monitor at the risk of our safety."[136]

Ron Paul, a former Republican member of Congress and prominent libertarian, thanked Snowden and Greenwald and denounced the mass surveillance as unhelpful and damaging, urging instead more transparency in U.S. government actions.[137] He called Congress "derelict in giving that much power to the government," and said that had he been elected president, he would have ordered searches only when there was probable cause of a crime having been committed, which he said was not how the PRISM program was being operated.[138]

New York Times columnist Thomas L. Friedman defended limited government surveillance programs intended to protect the American people from terrorist acts:

Yes, I worry about potential government abuse of privacy from a program designed to prevent another 9/11—abuse that, so far, does not appear to have happened. But I worry even more about another 9/11. ... If there were another 9/11, I fear that 99 percent of Americans would tell their members of Congress: "Do whatever you need to do to, privacy be damned, just make sure this does not happen again." That is what I fear most. That is why I'll reluctantly, very reluctantly, trade off the government using data mining to look for suspicious patterns in phone numbers called and e-mail addresses—and then have to go to a judge to get a warrant to actually look at the content under guidelines set by Congress—to prevent a day where, out of fear, we give government a license to look at anyone, any e-mail, any phone call, anywhere, anytime.[139]

Political commentator David Brooks similarly cautioned that government data surveillance programs are a necessary evil: "if you don't have mass data sweeps, well, then these agencies are going to want to go back to the old-fashioned eavesdropping, which is a lot more intrusive."[140]

Conservative commentator Charles Krauthammer worried less about the legality of PRISM and other NSA surveillance tools than about the potential for their abuse without more stringent oversight. "The problem here is not constitutionality. ... We need a toughening of both congressional oversight and judicial review, perhaps even some independent outside scrutiny. Plus periodic legislative revision—say, reauthorization every couple of years—in light of the efficacy of the safeguards and the nature of the external threat. The object is not to abolish these vital programs. It's to fix them."[141]

In a blog post, David Simon, the creator of The Wire, compared the NSA's programs, including PRISM, to a 1980s effort by the City of Baltimore to add dialed number recorders to all pay phones to know which individuals were being called by the callers;[142] the city believed that drug traffickers were using pay phones and pagers, and a municipal judge allowed the city to place the recorders. The placement of the dialers formed the basis of the show's first season. Simon argued that the media attention regarding the NSA programs is a "faux scandal."[142][143] Simon had stated that many classes of people in American society had already faced constant government surveillance.

Political activist, and frequent critic of U.S. government policies, Noam Chomsky argued, "Governments should not have this capacity. But governments will use whatever technology is available to them to combat their primary enemy – which is their own population."[144]

A CNN/Opinion Research Corporation poll conducted June 11 through 13 and released in 2013 found that 66% of Americans generally supported the program.[145][146][Notes 1] However, a Quinnipiac University poll conducted June 28 through July 8 and released in 2013 found that 45% of registered voters think the surveillance programs have gone too far, with 40% saying they do not go far enough, compared to 25% saying they had gone too far and 63% saying not far enough in 2010.[147] Other polls have shown similar shifts in public opinion as revelations about the programs were leaked.[148][149]

In terms of economic impact, a study released in August by the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation[150] found that the disclosure of PRISM could cost the U.S. economy between $21.5 and $35 billion in lost cloud computing business over three years.[151][152][153][154]

International

[edit]Sentiment around the world was that of general displeasure upon learning the extent of world communication data mining. Some national leaders spoke against the NSA and some spoke against their own national surveillance. One national minister had scathing comments on the National Security Agency's data-mining program, citing Benjamin Franklin: "The more a society monitors, controls, and observes its citizens, the less free it is."[155] Some question if the costs of hunting terrorists now overshadows the loss of citizen privacy.[156][157]

Nick Xenophon, an Australian independent senator, asked Bob Carr, the Australian Minister of Foreign Affairs, if e-mail addresses of Australian parliamentarians were exempt from PRISM, Mainway, Marina, and/or Nucleon. After Carr replied that there was a legal framework to protect Australians but that the government would not comment on intelligence matters, Xenophon argued that this was not a specific answer to his question.[158]

Taliban spokesperson Zabiullah Mujahid said, "We knew about their past efforts to trace our system. We have used our technical resources to foil their efforts and have been able to stop them from succeeding so far."[159][160] However CNN has reported that terrorist groups have changed their "communications behaviors" in response to the leaks.[65]

In 2013 the Cloud Security Alliance surveyed cloud computing stakeholders about their reactions to the US PRISM spying scandal. About 10% of non-US residents indicated that they had cancelled a project with a US-based cloud computing provider, in the wake of PRISM; 56% said that they would be less likely to use a US-based cloud computing service. The Alliance predicted that US cloud computing providers might lose as much as €26 billion and 20% of its share of cloud services in foreign markets because of the PRISM spying scandal.[161]

China

[edit]

Reactions of internet users in China were mixed between viewing a loss of freedom worldwide and seeing state surveillance coming out of secrecy. The story broke just before U.S. President Barack Obama and General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party Xi Jinping met in California.[162][163] When asked about NSA hacking China, the spokeswoman of Ministry of Foreign Affairs of China said, "China strongly advocates cybersecurity."[164] The party-owned newspaper Liberation Daily described this surveillance like Nineteen Eighty-Four-style.[165] Hong Kong legislators Gary Fan and Claudia Mo wrote a letter to Obama stating, "the revelations of blanket surveillance of global communications by the world's leading democracy have damaged the image of the U.S. among freedom-loving peoples around the world."[166] Ai Weiwei, a Chinese dissident, said, "Even though we know governments do all kinds of things I was shocked by the information about the US surveillance operation, Prism. To me, it's abusively using government powers to interfere in individuals' privacy. This is an important moment for international society to reconsider and protect individual rights."[167]

Europe

[edit]Sophie in 't Veld, a Dutch Member of the European Parliament, called PRISM "a violation of EU laws."[168]

The German Federal Commissioner for Data Protection and Freedom of Information, Peter Schaar, condemned the program as "monstrous."[169] He further added that White House claims do "not reassure me at all" and that "given the large number of German users of Google, Facebook, Apple or Microsoft services, I expect the German government ... is committed to clarification and limitation of surveillance." Steffen Seibert, press secretary of the Chancellor's office, announced that Angela Merkel will put these issues on the agenda of the talks with Barack Obama during his pending visit in Berlin.[170] Wolfgang Schmidt, a former lieutenant colonel with the Stasi, said that the Stasi would have seen such a program as a "dream come true" since the Stasi lacked the technology that made PRISM possible.[171] Schmidt expressed opposition, saying, "It is the height of naivete to think that once collected this information won't be used. This is the nature of secret government organizations. The only way to protect the people's privacy is not to allow the government to collect their information in the first place."[100] Many Germans organized protests, including one at Checkpoint Charlie, when Obama went to Berlin to speak. Matthew Schofield of the McClatchy Washington Bureau said, "Germans are dismayed at Obama's role in allowing the collection of so much information."[100]

The Italian president of the Guarantor for the protection of personal data, Antonello Soro, said that the surveillance dragnet "would not be legal in Italy" and would be "contrary to the principles of our legislation and would represent a very serious violation."[172]

CNIL (French data protection watchdog) ordered Google to change its privacy policies within three months or risk fines up to 150,000 euros. Spanish Agency of data protection (AEPD) planned to fine Google between 40,000 and 300,000 euros if it failed to clear stored data on the Spanish users.[173]

William Hague, the foreign secretary of the United Kingdom, dismissed accusations that British security agencies had been circumventing British law by using information gathered on British citizens by PRISM[174] saying, "Any data obtained by us from the United States involving UK nationals is subject to proper UK statutory controls and safeguards."[174] David Cameron said Britain's spy agencies that received data collected from PRISM acted within the law: "I'm satisfied that we have intelligence agencies that do a fantastically important job for this country to keep us safe, and they operate within the law."[174][175] Malcolm Rifkind, the chairman of parliament's Intelligence and Security Committee, said that if the British intelligence agencies were seeking to know the content of emails about people living in the UK, then they actually have to get lawful authority.[175] The UK's Information Commissioner's Office was more cautious, saying it would investigate PRISM alongside other European data agencies: "There are real issues about the extent to which U.S. law agencies can access personal data of UK and other European citizens. Aspects of U.S. law under which companies can be compelled to provide information to U.S. agencies potentially conflict with European data protection law, including the UK's own Data Protection Act. The ICO has raised this with its European counterparts, and the issue is being considered by the European Commission, who are in discussions with the U.S. Government."[168]

Tim Berners-Lee, the inventor of the World Wide Web, accused western governments of practicing hypocrisy, as they conducted spying on the internet while they criticized other countries for spying on the internet. He stated that internet spying can make people feel reluctant to access intimate and private information that is important to them.[176] In a statement given to Financial Times following the Snowden revelations, Berners-Lee stated "Unwarranted government surveillance is an intrusion on basic human rights that threatens the very foundations of a democratic society."[177]

India

[edit]Minister of External Affairs Salman Khurshid defended the PRISM program saying, "This is not scrutiny and access to actual messages. It is only computer analysis of patterns of calls and emails that are being sent. It is not actually snooping specifically on content of anybody's message or conversation. Some of the information they got out of their scrutiny, they were able to use it to prevent serious terrorist attacks in several countries."[178] His comments contradicted his Foreign Ministry's characterization of violations of privacy as "unacceptable."[179][180] When the then Minister of Communications and Information Technology Kapil Sibal was asked about Khurshid's comments, he refused to comment on them directly, but said, "We do not know the nature of data or information sought [as part of PRISM]. Even the external ministry does not have any idea."[181] The media felt that Khurshid's defence of PRISM was because the India government was rolling out the Central Monitoring System (CMS), which is similar to the PRISM program.[182][183][184]

Khurshid's comments were criticized by the Indian media,[185][186] as well as opposition party CPI(M) who stated, "The UPA government should have strongly protested against such surveillance and bugging. Instead, it is shocking that Khurshid has sought to justify it. This shameful remark has come at a time when even the close allies of the US like Germany and France have protested against the snooping on their countries."[187]

Rajya Sabha MP P. Rajeev told The Times of India that "The act of the USA is a clear violation of Vienna convention on diplomatic relations. But Khurshid is trying to justify it. And the speed of the government of India to reject the asylum application of Edward Snowden is shameful."[188]

Legal aspects

[edit]Applicable law and practice

[edit]On June 8, 2013, the Director of National Intelligence issued a fact sheet stating that PRISM "is not an undisclosed collection or data mining program," but rather "an internal government computer system" used to facilitate the collection of foreign intelligence information "under court supervision, as authorized by Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) (50 U.S.C. § 1881a)."[55] Section 702 provides that "the Attorney General and the Director of National Intelligence may authorize jointly, for a period of up to 1 year from the effective date of the authorization, the targeting of persons reasonably believed to be located outside the United States to acquire foreign intelligence information."[189] In order to authorize the targeting, the attorney general and Director of National Intelligence need to obtain an order from the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISA Court) pursuant to Section 702 or certify that "intelligence important to the national security of the United States may be lost or not timely acquired and time does not permit the issuance of an order."[189] When requesting an order, the attorney general and Director of National Intelligence must certify to the FISA Court that "a significant purpose of the acquisition is to obtain foreign intelligence information."[189] They do not need to specify which facilities or property will be targeted.[189]

After receiving a FISA Court order or determining that there are emergency circumstances, the attorney general and Director of National Intelligence can direct an electronic communication service provider to give them access to information or facilities to carry out the targeting and keep the targeting secret.[189] The provider then has the option to: (1) comply with the directive; (2) reject it; or (3) challenge it with the FISA Court. If the provider complies with the directive, it is released from liability to its users for providing the information and is reimbursed for the cost of providing it,[189] while if the provider rejects the directive, the attorney general may request an order from the FISA Court to enforce it.[189] A provider that fails to comply with the FISA Court's order can be punished with contempt of court.[189]

Finally, a provider can petition the FISA Court to reject the directive.[189] In case the FISA Court denies the petition and orders the provider to comply with the directive, the provider risks contempt of court if it refuses to comply with the FISA Court's order.[189] The provider can appeal the FISA Court's denial to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court of Review and then appeal the Court of Review's decision to the Supreme Court by a writ of certiorari for review under seal.[189]

The Senate Select Committee on Intelligence and the FISA Courts had been put in place to oversee intelligence operations in the period after the death of J. Edgar Hoover. Beverly Gage of Slate said, "When they were created, these new mechanisms were supposed to stop the kinds of abuses that men like Hoover had engineered. Instead, it now looks as if they have come to function as rubber stamps for the expansive ambitions of the intelligence community. J. Edgar Hoover no longer rules Washington, but it turns out we didn't need him anyway."[190]

Litigation

[edit]| Date | Litigant | Description |

|---|---|---|

| June 11, 2013 | American Civil Liberties Union | Lawsuit filed against the NSA citing that the "Mass Call Tracking Program" (as the case terms PRISM) "violates Americans' constitutional rights of free speech, association, and privacy" and constitutes "dragnet" surveillance, in violation of the First and Fourth Amendments to the Constitution, and thereby also "exceeds the authority granted by 50 U.S.C. § 1861, and thereby violates 5 U.S.C. § 706."[191] The case was joined by Yale Law School, on behalf of its Media Freedom and Information Access Clinic.[192] |

| June 11, 2013 | FreedomWatch USA | Class action lawsuit against government bodies and officials believed responsible for PRISM, and 12 companies (including Apple, Microsoft, Google, Facebook, and Skype and their chief executives) who have been disclosed as providing or making available mass information about their users' communications and data to the NSA under the PRISM program or related programs. The case cites the First, Fourth, and Fifth Amendments to the Constitution, as well as breach of 18 U.S.C. §§2702 (disclosure of communications records), and asks the court to rule that the program operates outside its legal authority (s.215 of the Patriot Act). The class includes the plaintiffs and[193]

In November 2017, the district court dismissed the case. |

| February 18, 2014 | Rand Paul and Freedom Works, Inc. | Lawsuit filed against President Barack Obama, James R. Clapper, as Director of National Intelligence, Keith B. Alexander, as director of the NSA, James B. Comey, as director of the FBI, in the United States District Court for the District of Columbia. The case contends that the Defendants are violating the Fourth Amendment of the United States by collecting phone metadata. The case is currently stayed pending the outcome of the government's appeal in the FreedomWatch USA/Klayman case. |

| June 2, 2014 | Elliott J. Schuchardt | Lawsuit filed against President Barack Obama, James R. Clapper, as Director of National Intelligence, Admiral Michael R. Rogers, as director of the NSA, James B. Comey, as director of the FBI, in the United States District Court for the Western District of Pennsylvania. The case contends that the Defendants are violating the Fourth Amendment of the United States by collecting the full content of e-mail in the United States. The complaint asks the Court to find the Defendants' program unconstitutional, and seeks an injunction. The court is currently considering the government's motion to dismiss this case. |

Analysis of legal issues

[edit]Laura Donohue, a law professor at the Georgetown University Law Center and its Center on National Security and the Law, has called PRISM and other NSA mass surveillance programs unconstitutional.[194]

Woodrow Hartzog, an affiliate at Stanford Law School's Center for Internet and Society commented that "[The ACLU will] likely have to demonstrate legitimate First Amendment harms (such as chilling effects) or Fourth Amendment harms (perhaps a violation of a reasonable expectation of privacy) ... Is it a harm to merely know with certainty that you are being monitored by the government? There's certainly an argument that it is. People under surveillance act differently, experience a loss of autonomy, are less likely to engage in self exploration and reflection, and are less willing to engage in core expressive political activities such as dissenting speech and government criticism. Such interests are what First and Fourth Amendment seek to protect."[195]

Legality of the FISA Amendments Act

[edit]The FISA Amendments Act (FAA) Section 702 is referenced in PRISM documents detailing the electronic interception, capture and analysis of metadata. Many reports and letters of concern written by members of Congress suggest that this section of FAA in particular is legally and constitutionally problematic, such as by targeting U.S. persons, insofar as "Collections occur in U.S." as published documents indicate.[196][197][198][199]

The ACLU has asserted the following regarding the FAA: "Regardless of abuses, the problem with the FAA is more fundamental: the statute itself is unconstitutional."[200]

Senator Rand Paul is introducing new legislation called the Fourth Amendment Restoration Act of 2013 to stop the NSA or other agencies of the United States government from violating the Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution using technology and big data information systems like PRISM and Boundless Informant.[201][202]

Programs sharing the name PRISM

[edit]Besides the information collection program started in 2007, there are two other programs sharing the name PRISM:[203]

- The Planning tool for Resource Integration, Synchronization and Management (PRISM), a web tool used by US military intelligence to send tasks and instructions to data collection platforms deployed to military operations.[204]

- The Portal for Real-time Information Sharing and Management (PRISM), whose existence was revealed by the NSA in July 2013.[203] This is an internal NSA program for real-time sharing of information which is apparently located in the NSA's Information Assurance Directorate.[203] The NSA's Information Assurance Directorate (IAD) is a very secretive division which is responsible for safeguarding U.S. government and military secrets by implementing sophisticated encryption techniques.[203]

Related NSA programs

[edit]

Parallel programs, known collectively as SIGADs gather data and metadata from other sources, each SIGAD has a set of defined sources, targets, types of data collected, legal authorities, and software associated with it. Some SIGADs have the same name as the umbrella under which they sit, BLARNEY's (the SIGAD) summary, set down in the slides alongside a cartoon insignia of a shamrock and a leprechaun hat, describes it as "an ongoing collection program that leverages IC [intelligence community] and commercial partnerships to gain access and exploit foreign intelligence obtained from global networks."

Some SIGADs, like PRISM, collect data at the ISP level, but others take it from the top-level infrastructure. This type of collection is known as "upstream". Upstream collection includes programs known by the blanket terms BLARNEY, FAIRVIEW, OAKSTAR and STORMBREW, under each of these are individual SIGADs. Data that is integrated into a SIGAD can be gathered in other ways besides upstream, and from the service providers, for instance it can be collected from passive sensors around embassies, or even stolen from an individual computer network in a hacking attack.[205][206][207][208][209] Not all SIGADs involve upstream collection, for instance, data could be taken directly from a service provider, either by agreement (as is the case with PRISM), by means of hacking, or other ways.[210][211][212] According to the Washington Post, the much less known MUSCULAR program, which directly taps the unencrypted data inside the Google and Yahoo private clouds, collects more than twice as many data points compared to PRISM.[213] Because the Google and Yahoo clouds span the globe, and because the tap was done outside of the United States, unlike PRISM, the MUSCULAR program requires no (FISA or other type of) warrants.[214]

See also

[edit]- Central Monitoring System

- Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act (CALEA), a U.S. wiretapping law passed in 1994

- DRDO NETRA

- ECHELON, a signals intelligence collection and analysis network operated on behalf of Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States

- Economic espionage

- Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution

- INDECT, European Union automatic threat detection research project

- Information Awareness Office, a defunct DARPA project

- Law Enforcement Information Exchange

- Lawful interception

- List of NSA controversies

- Mass surveillance

- Muscular (surveillance program)

- NSA call database, contains call detail information for hundreds of billions of telephone calls made through the largest U.S. telephone carriers

- Room 641A

- Signals intelligence

- SORM, Russian telephone and internet surveillance project

- Surveillance

- Targeted surveillance

- Tempora, the data-gathering project run by the British GCHQ

- TURBINE (US government project)

- Utah Data Center, a data storage facility supporting the U.S. Intelligence Community

Notes

[edit]- ^ The precise question was: [F]or the past few years the Obama administration has reportedly been gathering and analyzing information from major internet companies about audio and video chats, photographs, e-mails, and documents involving people in other countries in an attempt to locate suspected terrorists. The government reportedly does not target internet usage by US citizens and if such data is collected, it is kept under strict controls. Do you think the Obama administration was right or wrong in gathering and analyzing that internet data?

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Gellman, Barton; Poitras, Laura (June 6, 2013). "US Intelligence Mining Data from Nine U.S. Internet Companies in Broad Secret Program". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 6, 2013. Retrieved June 15, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Greenwald, Glenn; MacAskill, Ewen (June 6, 2013). "NSA Taps in to Internet Giants' Systems to Mine User Data, Secret Files Reveal – Top-Secret Prism Program Claims Direct Access to Servers of Firms Including Google, Apple and Facebook – Companies Deny Any Knowledge of Program in Operation Since 2007 – Obama Orders US to Draw Up Overseas Target List for Cyber-Attacks". The Guardian. Archived from the original on February 7, 2019. Retrieved June 15, 2013.

- ^ Braun, Stephen; Flaherty, Anne; Gillum, Jack; Apuzzo, Matt (June 15, 2013). "Secret to PRISM Program: Even Bigger Data Seizures". Associated Press. Archived from the original on September 10, 2013. Retrieved June 18, 2013.

- ^ Chappell, Bill (June 6, 2013). "NSA Reportedly Mines Servers of US Internet Firms for Data". NPR. The Two-Way (blog of NPR). Archived from the original on June 13, 2013. Retrieved June 15, 2013.

- ^ ZDNet Community; Whittaker, Zack (June 8, 2013). "PRISM: Here's How the NSA Wiretapped the Internet". ZDNet. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on June 14, 2013. Retrieved June 15, 2013.

- ^ Barton Gellman & Ashkan Soltani (October 30, 2013). "NSA infiltrates links to Yahoo, Google data centers worldwide, Snowden documents say". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 6, 2014. Retrieved October 31, 2013.

- ^ Siobhan Gorman & Jennifer Valentiono-Devries (August 20, 2013). "New Details Show Broader NSA Surveillance Reach - Programs Cover 75% of Nation's Traffic, Can Snare Emails". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved August 21, 2013.

- ^ "Graphic: How the NSA Scours Internet Traffic in the U.S." The Wall Street Journal. August 20, 2013. Retrieved August 21, 2013.

- ^ Jennifer Valentiono-Devries & Siobhan Gorman (August 20, 2013). "What You Need to Know on New Details of NSA Spying". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved August 21, 2013.

- ^ Lee, Timothy B. (June 6, 2013). "How Congress Unknowingly Legalized PRISM in 2007". Wonkblog (blog of The Washington Post). Retrieved July 4, 2013.

- ^ Johnson, Luke (July 1, 2013). "George W. Bush Defends PRISM: 'I Put That Program in Place to Protect the Country'" Archived July 2, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. The Huffington Post. Retrieved July 4, 2013.

- ^ Office of the Director of National Intelligence (June 8, 2013). "Facts on the Collection of Intelligence Pursuant to Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act" (PDF). dni.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 2, 2013. Retrieved July 25, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Mezzofiore, Gianluca (June 17, 2013). "NSA Whistleblower Edward Snowden: Washington Snoopers Are Criminals" Archived September 17, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. International Business Times. Retrieved June 30, 2013.

- ^ MacAskill, Ewan (August 23, 2013). "NSA paid millions to cover Prism compliance costs for tech companies". Archived from the original on November 3, 2015. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Staff (June 6, 2013). "NSA Slides Explain the PRISM Data-Collection Program". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 15, 2014. Retrieved June 15, 2013.

- ^ John D Bates (October 3, 2011). "[redacted]" (PDF). p. 71. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 24, 2013. Retrieved August 21, 2013.

- ^ a b c Savage, Charlie; Wyatt, Edward; Baker, Peter (June 6, 2013). "U.S. Says It Gathers Online Data Abroad". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 16, 2017. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- ^ Greenwald, Glenn (June 5, 2013). "NSA Collecting Phone Records of Millions of Verizon Customers Daily – Top Secret Court Order Requiring Verizon to Hand Over All Call Data Shows Scale of Domestic Surveillance under Obama". The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 16, 2013. Retrieved June 15, 2013.

- ^ Staff (June 6, 2013). "Intelligence Chief Blasts NSA Leaks, Declassifies Some Details about Phone Program Limits". Associated Press (via The Washington Post). Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved June 15, 2013.

- ^ Ovide, Shira (June 8, 2013). "U.S. Official Releases Details of Prism Program". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on October 9, 2013. Retrieved June 15, 2013.

- ^ Madison, Lucy (June 19, 2013). "Obama defends "narrow" surveillance programs". CBS News. Archived from the original on June 27, 2013. Retrieved June 30, 2013.

- ^ Johnson, Kevin; Martin, Scott; O'Donnell, Jayne; Winter, Michael (June 15, 2013). "NSA taps data from 9 major Net firms". USA Today. Archived from the original on June 7, 2013. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- ^ MacAskill, Ewen; Borger, Julian; Hopkins, Nick; Davies, Nick; Ball, James (June 21, 2013). "GCHQ taps fibre-optic cables for secret access to world's communications" Archived October 17, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. The Guardian. Retrieved June 30, 2013.

- ^ (June 22, 2013). "GCHQ data-tapping claims nightmarish, says German justice minister" Archived January 19, 2019, at the Wayback Machine. BBC News. Retrieved June 30, 2013.

- ^ Clayton, Mark (June 22, 2013). "When in doubt, NSA searches information on Americans". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on June 26, 2013. Retrieved June 30, 2013 – via Yahoo! News.

- ^ "Procedures used by NSA to target non-US persons: Exhibit A – full document". The Guardian. June 20, 2013. Archived from the original on January 3, 2017. Retrieved June 29, 2013.

- ^ Bump, Philip (June 20, 2013). "The NSA Guidelines for Spying on You Are Looser Than You've Been Told". The Atlantic Wire. Archived from the original on June 23, 2013. Retrieved June 29, 2013.

- ^ Teodori, Michael. "The Use of Personal Data in Post 9/11 Counter-Terrorism: European and American approaches compared". Academia.

- ^ "Espionnage de la NSA: tous les documents publiés par 'Le Monde'". Le Monde. October 21, 2013. Archived from the original on October 22, 2013. Retrieved October 22, 2013.

- ^ "NSA Prism program slides". The Guardian. November 1, 2013. Archived from the original on March 20, 2014. Retrieved March 19, 2014.