Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Remote control

View on Wikipedia

A remote control, also known colloquially as a remote or clicker,[1] is an electronic device used to operate another device from a distance, usually wirelessly. In consumer electronics, a remote control can be used to operate devices such as a television set, DVD player or other digital home media appliance. A remote control can allow operation of devices that are out of convenient reach for direct operation of controls. They function best when used from a short distance. This is primarily a convenience feature for the user. In some cases, remote controls allow a person to operate a device that they otherwise would not be able to reach, as when a garage door opener is triggered from outside.

Early television remote controls (1956–1977) used ultrasonic tones. Present-day remote controls are commonly consumer infrared devices which send digitally coded pulses of infrared radiation. They control functions such as power, volume, channels, playback, track change, energy, fan speed, and various other features. Remote controls for these devices are usually small wireless handheld objects with an array of buttons. They are used to adjust various settings such as television channel, track number, and volume. The remote control code, and thus the required remote control device, is usually specific to a product line. However, there are universal remotes, which emulate the remote control made for most major brand devices.

Remote controls in the 2000s include Bluetooth or Wi-Fi connectivity, motion sensor-enabled capabilities and voice control.[2][3] Remote controls for 2010s onward Smart TVs may feature a standalone keyboard on the rear side to facilitate typing, and be usable as a pointing device.[4]

History

[edit]Wired and wireless remote control was developed in the latter half of the 19th century to meet the need to control unmanned vehicles (for the most part military torpedoes).[5] These included a wired version by German engineer Werner von Siemens in 1870, and radio controlled ones by British engineer Ernest Wilson and C. J. Evans (1897)[6][7] and a prototype that inventor Nikola Tesla demonstrated in New York in 1898.[8] In 1903 Spanish engineer Leonardo Torres Quevedo introduced a radio based control system called the "Telekino" at the Paris Academy of Sciences,[9] which he hoped to use to control a dirigible airship of his own design. Unlike previous "on/off" techniques, the Telekino was able to execute a finite but not limited set of different mechanical actions using a single communication channel.[10][11] From 1904 to 1906 Torres chose to conduct Telekino testings in the form of a three-wheeled land vehicle with an effective range of 20 to 30 meters, and guiding a manned electrically powered boat, which demonstrated a standoff range of 2 kilometers.[12] The first remote-controlled model airplane flew in 1932,[citation needed] and the use of remote control technology for military purposes was worked on intensively during the Second World War, one result of this being the German Wasserfall missile.

By the late 1930s, several radio manufacturers offered remote controls for some of their higher-end models.[13] Most of these were connected to the set being controlled by wires, but the Philco Mystery Control (1939) was a battery-operated low-frequency radio transmitter,[14] thus making it the first wireless remote control for a consumer electronics device. Using pulse-count modulation, this also was the first digital wireless remote control.

Television remote controls

[edit]

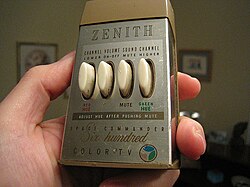

One of the first remote intended to control a television was developed by Zenith Radio Corporation in 1950. The remote, called Lazy Bones,[15] was connected to the television by a wire. A wireless remote control, the Flash-Matic,[15][16] was developed in 1955 by Eugene Polley. It worked by shining a beam of light onto one of four photoelectric cells,[17] but the cell did not distinguish between light from the remote and light from other sources.[18] The Flashmatic also had to be pointed very precisely at one of the sensors in order to work.[18][19]

In 1956, Robert Adler developed Zenith Space Command, a wireless remote.[15][20][21] It was mechanical and used ultrasound to change the channel and volume.[22][21] When the user pushed a button on the remote control, it struck a bar and clicked, hence they were commonly called "clickers", and the mechanics were similar to a pluck.[21][23] Each of the four bars emitted a different fundamental frequency with ultrasonic harmonics, and circuits in the television detected these sounds and interpreted them as channel-up, channel-down, sound-on/off, and power-on/off.[24]

Later, the rapid decrease in price of transistors made possible cheaper electronic remotes that contained a piezoelectric crystal that was fed by an oscillating electric current at a frequency near or above the upper threshold of human hearing, though still audible to dogs. The receiver contained a microphone attached to a circuit that was tuned to the same frequency. Some problems with this method were that the receiver could be triggered accidentally by naturally occurring noises or deliberately by metal against glass, for example, and some people could hear the lower ultrasonic harmonics.

In 1970, RCA introduced an all-electronic remote control that uses digital signals and metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistor (MOSFET) memory. This was widely adopted for color television, replacing motor-driven tuning controls.[25]

The impetus for a more complex type of television remote control came in 1973, with the development of the Ceefax teletext service by the BBC. Most commercial remote controls at that time had a limited number of functions, sometimes as few as three: next channel, previous channel, and volume/off. This type of control did not meet the needs of Teletext sets, where pages were identified with three-digit numbers. A remote control that selects Teletext pages would need buttons for each numeral from zero to nine, as well as other control functions, such as switching from text to picture, and the normal television controls of volume, channel, brightness, color intensity, etc. Early Teletext sets used wired remote controls to select pages, but the continuous use of the remote control required for Teletext quickly indicated the need for a wireless device. So BBC engineers began talks with one or two television manufacturers, which led to early prototypes in around 1977–1978 that could control many more functions. ITT was one of the companies and later gave its name to the ITT protocol of infrared communication.[26]

In 1980, the most popular remote control was the Starcom Cable TV Converter (from Jerrold Electronics, a division of General Instrument)[15][failed verification] which used 40-kHz sound to change channels. Then, a Canadian company, Viewstar, Inc., was formed by engineer Paul Hrivnak and started producing a cable TV converter with an infrared remote control. The product was sold through Philips for approximately $190 CAD. The Viewstar converter was an immediate success, the millionth converter being sold on March 21, 1985, with 1.6 million sold by 1989.[27][28]

Other remote controls

[edit]The Blab-off was a wired remote control created in 1952 that turned a TV's (television) sound on or off so that viewers could avoid hearing commercials.[29] In the 1980s Steve Wozniak of Apple started a company named CL 9. The purpose of this company was to create a remote control that could operate multiple electronic devices. The CORE unit (Controller Of Remote Equipment) was introduced in the fall of 1987. The advantage to this remote controller was that it could "learn" remote signals from different devices. It had the ability to perform specific or multiple functions at various times with its built-in clock. It was the first remote control that could be linked to a computer and loaded with updated software code as needed. The CORE unit never made a huge impact on the market. It was much too cumbersome for the average user to program, but it received rave reviews from those who could.[citation needed] These obstacles eventually led to the demise of CL 9, but two of its employees continued the business under the name Celadon. This was one of the first computer-controlled learning remote controls on the market.[30]

In the 1990s, cars were increasingly sold with electronic remote control door locks. These remotes transmit a signal to the car which locks or unlocks the door locks or unlocks the trunk. An aftermarket device sold in some countries is the remote starter. This enables a car owner to remotely start their car. This feature is most associated with countries with winter climates, where users may wish to run the car for several minutes before they intend to use it, so that the car heater and defrost systems can remove ice and snow from the windows.

Proliferation

[edit]

By the early 2000s, the number of consumer electronic devices in most homes greatly increased, along with the number of remotes to control those devices. According to the Consumer Electronics Association, an average US home has four remotes.[citation needed] To operate a home theater as many as five or six remotes may be required, including one for cable or satellite receiver, VCR or digital video recorder (DVR/PVR), DVD player, TV and audio amplifier. Several of these remotes may need to be used sequentially for some programs or services to work properly. However, as there are no accepted interface guidelines, the process is increasingly cumbersome. One solution used to reduce the number of remotes that have to be used is the universal remote, a remote control that is programmed with the operation codes for most major brands of TVs, DVD players, etc. In the early 2010s, many smartphone manufacturers began incorporating infrared emitters into their devices, thereby enabling their use as universal remotes via an included or downloadable app.[31]

Technique

[edit]The main technology used in home remote controls is infrared (IR) light. The signal between a remote control handset and the device it controls consists of pulses of infrared light, which is invisible to the human eye but can be seen through a digital camera, video camera or phone camera. The transmitter in the remote control handset sends out a stream of pulses of infrared light when the user presses a button on the handset. A transmitter is often a light-emitting diode (LED) which is built into the pointing end of the remote control handset. The infrared light pulses form a pattern unique to that button. The receiver in the device recognizes the pattern and causes the device to respond accordingly.[32]

Opto components and circuits

[edit]

Most remote controls for electronic appliances use a near infrared diode to emit a beam of light that reaches the device. A 940 nm wavelength LED is typical.[33] This infrared light is not visible to the human eye but picked up by sensors on the receiving device. Video cameras see the diode as if it produces visible purple light. With a single channel (single-function, one-button) remote control the presence of a carrier signal can be used to trigger a function. For multi-channel (normal multi-function) remote controls more sophisticated procedures are necessary: one consists of modulating the carrier with signals of different frequencies. After the receiver demodulates the received signal, it applies the appropriate frequency filters to separate the respective signals. One can often hear the signals being modulated on the infrared carrier by operating a remote control in very close proximity to an AM radio not tuned to a station. Today, IR remote controls almost always use a pulse width modulated code, encoded and decoded by a digital computer: a command from a remote control consists of a short train of pulses of carrier-present and carrier-not-present of varying widths.[citation needed]

Consumer electronics infrared protocols

[edit]Different manufacturers of infrared remote controls use different protocols to transmit the infrared commands. The RC-5 protocol that has its origins within Philips, uses, for instance, a total of 14 bits for each button press. The bit pattern is modulated onto a carrier frequency that, again, can be different for different manufacturers and standards, in the case of RC-5, the carrier is 36 kHz. Other consumer infrared protocols include the various versions of SIRCS used by Sony, the RC-6 from Philips, the Ruwido R-Step, and the NEC TC101 protocol.

Infrared, line of sight and operating angle

[edit]Since infrared (IR) remote controls use light, they require line of sight to operate the destination device. The signal can, however, be reflected by mirrors, just like any other light source. If operation is required where no line of sight is possible, for instance when controlling equipment in another room or installed in a cabinet, many brands of IR extenders are available for this on the market. Most of these have an IR receiver, picking up the IR signal and relaying it via radio waves to the remote part, which has an IR transmitter mimicking the original IR control. Infrared receivers also tend to have a more or less limited operating angle, which mainly depends on the optical characteristics of the phototransistor. However, it is easy to increase the operating angle using a matte transparent object in front of the receiver.

Radio remote control systems

[edit]

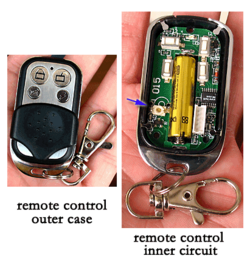

Radio remote control (RF remote control) is used to control distant objects using a variety of radio signals transmitted by the remote control device. As a complementary method to infrared remote controls, the radio remote control is used with electric garage door or gate openers, automatic barrier systems, burglar alarms and industrial automation systems. Standards used for RF remotes are: Bluetooth AVRCP, Zigbee (RF4CE), Z-Wave. Most remote controls use their own coding, transmitting from 8 to 100 or more pulses, fixed or Rolling code, using OOK or FSK modulation. Also, transmitters or receivers can be universal, meaning they are able to work with many different codings. In this case, the transmitter is normally called a universal remote control duplicator because it is able to copy existing remote controls, while the receiver is called a universal receiver because it works with almost any remote control in the market.

A radio remote control system commonly has two parts: transmit and receive. The transmitter part is divided into two parts, the RF remote control and the transmitter module. This allows the transmitter module to be used as a component in a larger application. The transmitter module is small, but users must have detailed knowledge to use it; combined with the RF remote control it is much simpler to use.

The receiver is generally one of two types: a super-regenerative receiver or a superheterodyne. The super-regenerative receiver works like that of an intermittent oscillation detection circuit. The superheterodyne works like the one in a radio receiver. The superheterodyne receiver is used because of its stability, high sensitivity and it has relatively good anti-interference ability, a small package and lower price.

Usage

[edit]Industry

[edit]A remote control is used for controlling substations, pump storage power stations and HVDC-plants. For these systems often PLC-systems working in the longwave range are used.

Power line remote control

[edit]A subset of Power-Line communication that sends remote control signals over energized AC power lines. This was used to remotely control home automation before the invention of WIFI connected smart switches.

Garage and gate

[edit]Garage and gate remote controls, also called clickers or openers, are very common especially in some countries such as the US, Australia, and the UK, where garage doors, gates and barriers are widely used. Such a remote is very simple by design, usually only one button, and some with more buttons to control several gates from one control. Such remotes can be divided into two categories by the encoder type used: fixed code and rolling code. If you find dip-switches in the remote, it is likely to be fixed code, an older technology which was widely used. However, fixed codes have been criticized for their (lack of) security, thus rolling code has been more and more widely used in later installations.

Military

[edit]

Remotely operated torpedoes were demonstrated in the late 19th century in the form of several types of remotely controlled torpedoes. The early 1870s saw remotely controlled torpedoes by John Ericsson (pneumatic), John Louis Lay (electric wire guided), and Victor von Scheliha (electric wire guided).[34]

The Brennan torpedo, invented by Louis Brennan in 1877 was powered by two contra-rotating propellers that were spun by rapidly pulling out wires from drums wound inside the torpedo. Differential speed on the wires connected to the shore station allowed the torpedo to be guided to its target, making it "the world's first practical guided missile".[35] In 1898 Nikola Tesla publicly demonstrated a "wireless" radio-controlled torpedo that he hoped to sell to the U.S. Navy.[36][37]

Archibald Low was known as the "father of radio guidance systems" for his pioneering work on guided rockets and planes during the First World War. In 1917, he demonstrated a remote-controlled aircraft to the Royal Flying Corps and in the same year built the first wire-guided rocket. As head of the secret RFC experimental works at Feltham, A. M. Low was the first person to use radio control successfully on an aircraft, an "Aerial Target". It was "piloted" from the ground by future world aerial speed record holder Henry Segrave.[38] Low's systems encoded the command transmissions as a countermeasure to prevent enemy intervention.[39] By 1918 the secret D.C.B. Section of the Royal Navy's Signals School, Portsmouth under the command of Eric Robinson V.C. used a variant of the Aerial Target's radio control system to control from ‘mother’ aircraft different types of naval vessels including a submarine.[40]

The military also developed several early remote control vehicles. In World War I, the Imperial German Navy employed FL-boats (Fernlenkboote) against coastal shipping. These were driven by internal combustion engines and controlled remotely from a shore station through several miles of wire wound on a spool on the boat. An aircraft was used to signal directions to the shore station. EMBs carried a high explosive charge in the bow and traveled at speeds of thirty knots.[41] The Soviet Red Army used remotely controlled teletanks during the 1930s in the Winter War against Finland and the early stages of World War II. A teletank is controlled by radio from a control tank at a distance of 500 to 1,500 meters, the two constituting a telemechanical group. The Red Army fielded at least two teletank battalions at the beginning of the Great Patriotic War. There were also remotely controlled cutters and experimental remotely controlled planes in the Red Army.

Remote controls in military usage employ jamming and countermeasures against jamming. Jammers are used to disable or sabotage the enemy's use of remote controls. The distances for military remote controls also tend to be much longer, up to intercontinental distance satellite-linked remote controls used by the U.S. for their unmanned airplanes (drones) in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Pakistan. Remote controls are used by insurgents in Iraq and Afghanistan to attack coalition and government troops with roadside improvised explosive devices, and terrorists in Iraq are reported in the media to use modified TV remote controls to detonate bombs.[42]

Space

[edit]

In the winter of 1971, the Soviet Union explored the surface of the Moon with the lunar vehicle Lunokhod 1, the first roving remote-controlled robot to land on another celestial body. Remote control technology is also used in space travel, for instance, the Soviet Lunokhod vehicles were remote-controlled from the ground. Many space exploration rovers can be remotely controlled, though vast distance to a vehicle results in a long time delay between transmission and receipt of a command.

PC control

[edit]Existing infrared remote controls can be used to control PC applications.[citation needed] Any application that supports shortcut keys can be controlled via infrared remote controls from other home devices (TV, VCR, AC).[citation needed] This is widely used[citation needed] with multimedia applications for PC based home theater systems. For this to work, one needs a device that decodes IR remote control data signals and a PC application that communicates to this device connected to PC. A connection can be made via serial port, USB port or motherboard IrDA connector. Such devices are commercially available but can be homemade using low-cost microcontrollers.[citation needed] LIRC (Linux IR Remote control) and WinLIRC (for Windows) are software packages developed for the purpose of controlling PC using TV remote and can be also used for homebrew remote with lesser modification.

Photography

[edit]

Remote controls are used in photography, in particular to take long-exposure shots. Many action cameras such as the GoPros[43] as well as standard DSLRs including Sony's Alpha series [44] incorporate Wi-Fi based remote control systems. These can often be accessed and even controlled via cell-phones and other mobile devices.[45]

Video games

[edit]

Video game consoles had not used wireless controllers until recently,[when?] mainly because of the difficulty involved in playing the game while keeping the infrared transmitter pointed at the console. Early wireless controllers were cumbersome and when powered on alkaline batteries, lasted only a few hours before they needed replacement. Some wireless controllers were produced by third parties, in most cases using a radio link instead of infrared. Even these were very inconsistent, and in some cases, had transmission delays, making them virtually useless. Some examples include the Double Player for NES, the Master System Remote Control System and the Wireless Dual Shot for the PlayStation.

The first official wireless game controller made by a first party manufacturer was the CX-42 for Atari 2600. The Philips CD-i 400 series also came with a remote control, the WaveBird was also produced for the GameCube. In the seventh generation of gaming consoles, wireless controllers became standard. Some wireless controllers, such as those of the PlayStation 3 and Wii, use Bluetooth. Others, like the Xbox 360, use proprietary wireless protocols.

Standby power

[edit]To be turned on by a wireless remote, the controlled appliance must always be partly on, consuming standby power.[46]

Alternatives

[edit]Hand-gesture recognition has been researched as an alternative to remote controls for television sets.[47]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Greenfield, Rebecca (April 8, 2011). "Tech Etymology: TV Clicker". The Atlantic. Retrieved August 1, 2020.

- ^ James Wray and Ulf Stabe (December 5, 2011). "Microsoft brings TV voice control to Kinect". Thetechherald.com. Archived from the original on November 2, 2013. Retrieved January 2, 2013.

- ^ "PlayStation Move Navigation Controller". us.playstation.com.

- ^ Seng, Chong (August 30, 2012). "TP Vision Announces Philips 9000 Series Premium Smart LED TVs". www.hardwarezone.com.sg. Retrieved January 2, 2022.

- ^ H. R. Everett, Unmanned Systems of World Wars I and II, MIT Press - 2015, pages 79–80

- ^ H. R. Everett, Unmanned Systems of World Wars I and II, MIT Press - 2015, page 87

- ^ Everett, H. R. (November 6, 2015). Unmanned Systems of World Wars I and II. MIT Press. ISBN 9780262029223.

- ^ Tapan K. Sarkar, History of wireless, John Wiley and Sons, 2006, ISBN 0-471-71814-9, p. 276–278.

- ^ Sarkar 2006, page 97

- ^ Perez-Yuste, Antonio (2008). "Early Developments of Wireless Remote Control: The Telekino of Torres-Quevedo" (PDF). Proceedings of the IEEE. 96: 186–190. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2007.909931.

- ^ "1902 – Telekine (Telekino) – Leonardo Torres Quvedo (Spanish)". December 17, 2010.

- ^ H. R. Everett, Unmanned Systems of World Wars I and II, MIT Press - 2015, pages 91–95

- ^ "Radio Aims At Remote Control". Popular Science. Bonnier Corporation. November 1930.

- ^ "Philco Mystery Control".

- ^ a b c d "A history of the TV remote control as told through its advertising". Me-TV Network. Archived from the original on December 14, 2021. Retrieved August 17, 2018.

- ^ "Remote Background - Zenith Electronics". zenith.com. Retrieved August 17, 2018.

- ^ "Remembering Eugene Polley and his Flash-Matic remote (photos)". cnet.com. May 23, 2012. Retrieved August 17, 2018.

- ^ a b "Wireless remote control inventor zaps out at 96". theregister.co.uk. Retrieved August 17, 2018.

- ^ "Five Decades of Channel Surfing: History of the TV Remote Control". Archived from the original on January 16, 2008. Retrieved December 3, 2008.

- ^ Farhi, Paul. "The Inventor Who Deserves a Sitting Ovation." Washington Post. February 17, 2007.

- ^ a b c Marino, Andrew (July 29, 2023). "The buttons on Zenith's original "clicker" remote were a mechanical marvel". The Verge. Retrieved August 7, 2023.

- ^ Gertner, Jon (December 30, 2007). "The Lives They Lived - Robert Adler - Remote Control - Television". The New York Times. Retrieved August 17, 2018.

- ^ "1956: Zenith Space Commander Remote Control". Wired. Retrieved August 17, 2018.

- ^ "Robert Adler -TV wireless remote". MIT. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "Remote control for color tv goes the all-electronic route". Electronics. 43. McGraw-Hill Publishing Company: 102. April 1970.

RCA's Wayne Evans, Carl Moeller and Edward Milbourn tell how digital signals and MOS FET memory modules are used to replace motor-driven tuning controls

- ^ "SB-Projects: IR remote control: ITT protocol". Archived from the original on October 12, 2017. Retrieved April 7, 2013.

- ^ "Universal Remote Control History: Not Great, Just Good Enough". tedium.co. May 26, 2017. Retrieved August 17, 2018.

- ^ "Philips tops in converters". The Toronto Star: p. F03. November 29, 1980.

- ^ "Blab-Off". earlytelevision.org.

- ^ "Celadon Remote Control Systems Company Profile Page".

- ^ Seifert, Dan (April 24, 2013). "Back from the dead: why do 2013's best smartphones have IR blasters?". The Verge. Retrieved December 28, 2015.

- ^ ICT Roger Crawford – Heinemann IGCSE – Chapter 1 page 16

- ^ "What is the Wavelength of the Infrared Used in Remote Controls?". clickermart.com. December 18, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2018.

- ^ Edwyn Gray, Nineteenth-century torpedoes and their inventors, page 18

- ^ Gray, Edwyn (2004). Nineteenth-Century Torpedoes and Their Inventors. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-341-3.

- ^ US 613809, Tesla, Nikola, "Method of and apparatus for controlling mechanism of moving vessels or vehicles", published November 8, 1898

- ^ "Tesla – Master of Lightning". PBS.org. Retrieved September 24, 2008.

- ^ "A Brief History of Drones".

- ^ "The Dawn of the Drone" Steve Mills 2019 Casemate Publishers. Page 189 "In order further to safeguard against outside interference I may have a number of inertia wheels of variable speed, only one being correctly adjusted to pick up the timed signals and actuate the mechanism."

- ^ UK National Archives ADM 1/8539/253 Capabilities of distantly controlled boats. Reports of trials at Dover 28–31 May 1918

- ^ Lightoller, Charles Herbert (1935). Titanic and Other Ships. I. Nicholson and Watson.

- ^ Enders, David (October 2008). "Mahdi Army Bides its Time". The Progressive.

- ^ "GoPro - Cameras". shop.gopro.com.

- ^ "Sony α6000 E-mount camera with APS-C Sensor". Sony.

- ^ Lombardi, Gianluca. "By the Light of the Moon". Picture of the Week. ESO. Retrieved June 15, 2011.

- ^ "Home Office and Home Electronics". Archived from the original on August 25, 2009.

- ^ Freeman, William; Weissman, Craig (1995). "Television control by hand gestures" Archived November 14, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Mitsubishi Electric Research Laboratories.

External links

[edit] Media related to Remote control at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Remote control at Wikimedia Commons