Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

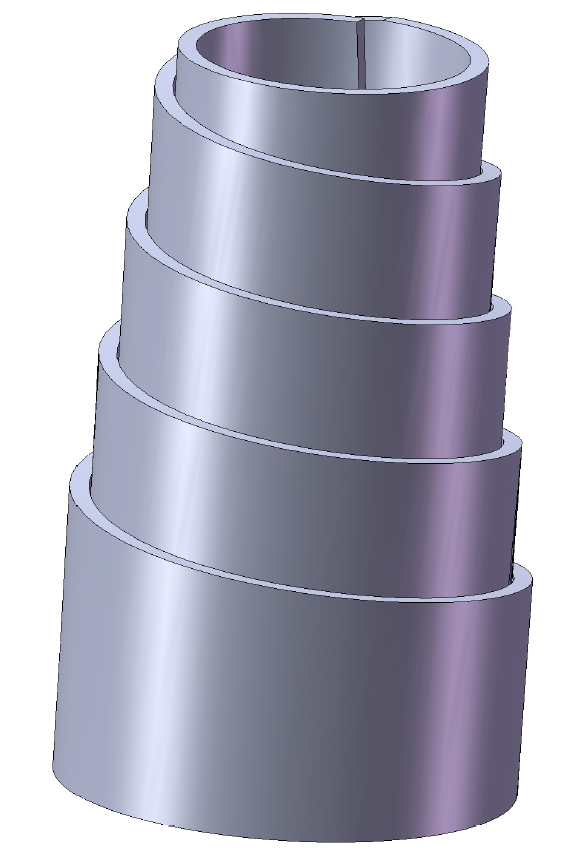

Volute spring

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2022) |

A volute spring, also known as a conical spring, is a compression spring in the form of a cone (somewhat like the classical volute decorative architectural ornament). Under compression, the coils slide past each other, thus enabling the spring to be compressed to a very short length in comparison with what would be possible with a more conventional helical spring.

There are two typical types of volute spring:

- The first has a shape for the initial spring steel (or other material for the wound spring) as a "V", with one end wider than the other

- The second is the double volute, having two "V" shapes facing away from each other, which forms a distorted cylinder having a wider diameter at the centre than at the ends, forming symmetric attachment points

Double volute springs can frequently be found as a component of garden pruning shears. Short posts anchored in each side of the handles, and inserted into each narrow end of the spring, keep the spring in position.

However, the applications of volute springs are not limited to such light-duty purposes as gardening shears. For example, volute springs are used to cushion the impact between railway cars and as a core element of the suspension system of Sherman tanks. A volute spring buffer device for railway cars was invented by John Brown in 1848.[1]

-

A double volute spring mounted in pruning shears. Under compression, the coils slide over each other, so affording longer travel.

-

A double volute spring

-

A single-sided conical, or volute spring

-

A volute suspension spring (1919)

-

Diagram showing volute spring within the buffer assembly of a railway car (with dotted lines showing compressed position), invented 1848

-

Volute springs within buffer assemblies on a railway car

-

Volute spring suspension on an M4 Sherman tank (in service 1942–1957)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "The Making of Modern Yorkshire", J.S. Fletcher (Google Books) Gives biographical details.

Volute spring

View on GrokipediaIntroduction

Definition and Function

A volute spring is a conical compression spring formed from a flat rectangular strip of material, wound into overlapping coils that decrease in diameter from the base to the apex.[6] This design creates a compact, tiered structure where the coils fit inside one another, distinguishing it from traditional helical springs.[1] In function, a volute spring serves as an energy storage and absorption device under axial compression loads. During compression, the overlapping coils slide past each other, starting from the largest base coil and progressively engaging inner coils, which provides a variable rate of resistance—increasing from linear to more exponential as deflection advances—and enables high load capacity within a small footprint.[1][7] This progressive behavior allows the spring to handle significant energy dissipation efficiently, with the solid height limited to the material strip's width rather than stacked coils.[6] Volute springs typically feature configurations suited to compression, such as open-coil setups for general use or closed-end variants with a dead coil for enhanced guidance and stability in precise applications.[1] Their distinctive spiral shape, evoking a volute scroll, imparts unique structural traits including self-centering alignment and inherent lateral stability, as the overlapping coils radially guide one another during operation, reducing buckling risk without external supports.[8][9]Comparison to Other Springs

Volute springs differ structurally from other common spring types in their use of flat metal strips wound into a conical or spiral configuration, where the overlapping coils provide self-guiding action during compression.[10] In contrast, cylindrical helical compression springs are fabricated from round wire formed into uniform cylindrical coils, while leaf springs consist of layered flat plates arranged in a semi-elliptical or cantilever shape, and disc springs (also known as Belleville washers) are individual or stacked conical discs.[11] Torsion springs, meanwhile, feature helical or spiral geometries optimized for twisting motion rather than axial compression.[11] This flat-strip, conical design in volute springs enhances lateral stability under off-axis loads compared to the more prone-to-buckling behavior of traditional helical springs.[12] In terms of performance, volute springs excel in compactness for high-load applications over leaf springs, which, while resilient, tend to be bulkier and require more space for equivalent load-bearing capacity.[13] However, they offer less versatility than torsion springs for storing and releasing rotational energy, as volute springs are primarily suited for axial compression with linear or progressive force-displacement characteristics.[11] Volute springs also demonstrate superior fatigue life and force repeatability under repeated cycling, attributes that surpass many helical designs in demanding environments.[11] Regarding suitability, volute springs are particularly well-adapted to space-constrained, high-impact scenarios where helical compression springs might buckle or deform laterally, thanks to their self-supporting coil overlap that minimizes kinking.[14] They fill a niche for robust shock absorption in compact forms, though they lack the precision for linear extension tasks better handled by extension springs, which resist pulling forces with hooked ends.[15] Overall, the primary spring categories encompass helical (coiled wire for versatile compression or tension), leaf (flat plates for heavy-duty support), disc (stacked washers for high-load stacking), and volute (spiral flat strips for guided compression).[10] Their energy absorption role aligns with helical springs but proves more efficient in tightly packaged designs requiring minimal height when compressed.[13]History

Invention and Early Applications

The volute spring, a conical compression spring designed to store energy by absorbing shocks, was patented by British industrialist and steelmaker John Brown in 1848 specifically as a buffer device for railway carriages.[16] This invention addressed the need for a more robust mechanism to cushion impacts during coupling and collisions, surpassing earlier buffer designs that relied on less efficient materials like rubber or simple coil springs.[17] The development of the volute spring occurred amid the Industrial Revolution's explosive growth in railway networks across Britain, where expanding freight and passenger traffic demanded innovative solutions for shock absorption to enhance safety and reduce wear on rolling stock.[16] Prior to this, railways often used rudimentary buffers prone to failure under heavy loads, exacerbating accidents in an era of rapid infrastructure buildup from the 1830s onward. Brown's expertise in Sheffield's steel industry enabled the precise forging of the spring's conical shape from high-quality steel, marking a pivotal advancement in mechanical resilience for transport systems.[18] Initial applications of the volute spring were concentrated in railway buffers and drawbar couplings on British lines, where it effectively mitigated collision forces by progressively compressing under load.[16] Adoption began immediately after the 1848 patent, with Brown supplying the London and North Western Railway and other major operators, but its use remained limited to heavy industrial rail settings due to the era's manufacturing challenges, including the difficulty of producing uniform conical coils without defects in steel quality or tempering.[16] By 1853, production had scaled to 150 sets per week, supplied to most principal British railway companies, demonstrating rapid integration into core infrastructure.[16] This post-1848 proliferation in British railways not only standardized volute springs in buffer assemblies but also influenced early mechanical engineering practices, establishing benchmarks for spring durability and load distribution in heavy-duty applications.[17] The invention's success underscored the interplay between metallurgical innovation and transport demands, paving the way for refined standards in railway engineering during the mid-19th century.[18]Evolution and Modern Adoption

The evolution of volute springs accelerated in the early 20th century with their introduction in military applications during World War I, where they were employed in tank suspensions such as the British Mark I to manage rugged terrain challenges at the Battle of the Somme in 1916.[19] Building on earlier 19th-century railway buffer designs dating to 1848, this milestone marked a shift toward more compact, high-energy-absorption systems capable of handling heavy loads in dynamic environments.[19] By the mid-20th century, advancements in design methodologies further refined volute springs for broader engineering use, particularly in automotive contexts. In 1943, the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) published standardized design methods that addressed variable spring rates and stress distribution, enabling more precise load handling and adaptation to vehicle suspensions.[20] These protocols improved reliability and performance, facilitating integration into diverse mechanical systems beyond initial military roles.[20] Post-World War II, volute springs saw widespread adoption in heavy machinery during the 1950s, driven by the transition from wartime production to industrial applications like shock absorption in construction and mining equipment.[19] This era's growth was supported by enhanced manufacturing scalability, evolving into contemporary testing for space applications in the 2020s, such as satellite deployable mechanisms where volute springs provide controlled release in launch restraint assemblies.[1] Key drivers of this modern adoption include material advancements, such as high-strength alloys for greater durability under extreme conditions, and computer numerical control (CNC) manufacturing techniques that allow precise coiling and customization for applications ranging from railroads to aerospace.[19][21] These innovations have enabled volute springs to scale effectively across industries while maintaining their core advantages in energy storage and compactness.[21]Design and Construction

Geometry and Dimensions

A volute spring features a core geometry consisting of a conical spiral formed by winding a flat strip of material, resulting in coils that decrease in diameter from a large base radius (R2) to a small apex radius (R1). This configuration allows the coils to overlap and slide against each other during compression.[1] Key dimensions of a volute spring include the number of active coils (Na), the strip thickness (t), and the strip width (w), which is proportional to the mean coil radius to maintain structural integrity. The solid height (Hs) under full compression is approximately Na multiplied by t, plus adjustments for end configurations, providing the minimum axial length when coils nest.[1] Volute springs exhibit variations such as open or nested coil arrangements, where nested designs stack multiple volutes for increased load capacity within the same envelope. Attachment terminations commonly include eye-ends or hooks to secure the spring to mating components.[22][21] Design prerequisites for volute springs emphasize space constraints and sufficient coil overlap, which are essential for the spring to function effectively under compression without excessive lateral expansion. Design often follows guidelines from the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE).[20][1][22]Materials and Manufacturing

Volute springs are primarily fabricated from materials that provide high elasticity and durability under compressive loads. High-carbon spring steel strips are commonly used for standard applications due to their balance of strength and cost-effectiveness.[23] For environments requiring corrosion resistance, stainless steels like SUS304 or SUS316 are selected, offering superior protection against rust in humid or chemical-exposed conditions.[21][24] In specialized cases involving high-cycle fatigue, such as electrical contacts or precision instruments, phosphor bronze or beryllium copper alloys are employed for their enhanced endurance under repeated loading.[25][26] Key material properties include high tensile strength, which enables the spring to withstand significant deformation without permanent set, and a shear modulus of approximately 79 GPa for steel variants, ensuring efficient energy storage and release. Fatigue resistance is critical, as these materials must endure millions of cycles without failure, with selection often tailored to the operating environment—for instance, oil-tempered spring steel is preferred in automotive settings for its improved sag resistance and thermal stability.[27][28][29] Manufacturing begins with forming the spring from flat strip, where the choice of hot or cold processes depends on the material thickness and precision needs; hot forming at 800–1000°C is used for thicker sections exceeding 5 mm to allow malleability, while cold coiling on CNC-controlled mandrels produces precise shapes for thinner stock under 5 mm.[21][30] Following coiling, the springs undergo heat treatment, including quenching in oil and tempering at 400–500°C to enhance hardness and relieve internal stresses.[31] Shot peening is then applied to induce beneficial compressive residual stresses on the surface, further improving fatigue life by mitigating crack initiation.[32] Quality assurance involves rigorous testing to verify performance. Dimensional inspection ensures adherence to specified geometry, such as strip width and thickness, using tools like calipers and optical comparators. Load testing compresses the spring to 1.5 times its rated capacity to confirm structural integrity without yielding, while fatigue cycling subjects samples to 10^5 to 10^6 repetitions at operational loads to assess long-term durability.[33][34][35]Mechanics

Working Principle

The working principle of a volute spring centers on its conical, spiral-wound configuration from a flat strip of material, which enables efficient energy absorption through controlled deformation under axial compression. When an axial force is applied, typically to the smaller-diameter eye at the apex, the overlapping coils begin to slide relative to one another, starting from the outer (larger) coils and progressing inward toward the apex. This sliding converts the linear input motion into a combination of frictional contact between coils and elastic deformation, dissipating some energy as heat while storing the majority as potential energy in the material. The conical taper facilitates this progressive engagement, with the larger coils, having a lower inherent stiffness due to their increased diameter, activating first to provide an initial soft response that stiffens as smaller coils toward the apex become involved.[1] Unlike helical compression springs, which primarily store energy through torsional shear in round wire, volute springs rely on bending of the flat strip, where the primary stresses are tensile on the outer fibers and compressive on the inner fibers of each coil segment. As the load increases, the centerline of the spring strip bends downward, allowing the coils to nest closely without buckling, as the overlapping design maintains radial stability and guides the motion axially. This nesting prevents lateral deflection, ensuring the spring remains self-guiding even under dynamic loads, with the energy storage capacity enhanced by the ability to achieve a high force in a compact solid height equal to the strip's initial thickness. The progressive rate characteristic arises from this sequential coil involvement, resulting in a load-deflection curve that starts linearly but becomes increasingly nonlinear (exponential) as outer, softer coils bottom out and inner stiffer coils contribute more to the resistance.[1][36][37] In operation, the frictional sliding between coils introduces hysteresis, which aids in damping vibrations by converting kinetic energy into thermal losses, making volute springs suitable for shock-absorbing roles. However, if overloaded beyond the design limits, excessive friction can lead to coil interlocking, where adjacent turns bind together, prematurely halting deflection and potentially causing structural failure or inaccurate force transmission. This failure mode underscores the importance of proper load management to avoid binding near the solid height.[1]Load-Deflection and Stress Analysis

The load-deflection behavior of a volute spring is characterized by its spring rate , defined as the ratio of applied load (in newtons) to corresponding deflection (in millimeters), expressed as .[38] For design purposes, an approximate expression for the spring rate treats the volute as a cantilever beam model, yielding , where is the Young's modulus of the material, is the strip width, is the strip thickness, and is the developed length of the strip along the coil path.[38] This model assumes linear elastic behavior prior to coil bottoming, with the rate increasing progressively as outer coils contact inner ones during compression.[1][37] Deflection under load is derived from beam theory applied to the volute's coiled strip, with the total axial deflection obtained by integrating the local bending contributions along the developed length, accounting for varying moments and geometry across coils. This results in a nearly linear load-deflection relationship until the largest coil bottoms out.[38] Stress analysis in volute springs focuses on the maximum bending stress, as the primary loading mode is flexural rather than torsional. The maximum tensile stress occurs at the outer fibers and is calculated as , where is the bending moment with as the mean coil radius, and is the moment of inertia.[38] Corrections are applied for curvature effects, incorporating a factor of approximately , and for the pitch angle via a term to adjust for helical inclination.[38] These ensure accurate prediction of stress distribution, which varies along the strip due to differing coil radii. While some analyses use equivalent shear stress for design, the fundamental stresses are from bending. The solid height , representing the fully compressed state, is determined as , where is the free height and is the maximum allowable deflection before complete bottoming of all coils.[1] The elastic potential energy stored in the spring under load is given by , assuming linear behavior within the working range.[39]Applications

Transportation and Automotive

Volute springs have been employed in railway applications since their invention in 1848 specifically for use in carriage buffers, where they absorb shocks during coupling and decoupling of cars.[40] These conical compression springs, made from wound flat steel wire, provide compact energy absorption for high-impact scenarios in rail systems, including buffers that cushion forces between freight and passenger cars.[41] In modern freight cars, nested volute springs are integrated into buffer systems to handle substantial loads, typically ranging from 100 to 500 kN over deflection travels of 100 to 200 mm, ensuring safe operation during shunting and transport.[42] This configuration leverages the springs' ability to stack multiple volutes for enhanced load distribution and progressive resistance, critical for heavy-haul rail networks. Their high load capacity stems from the conical design, which allows coils to slide without binding under compression.[8] Within automotive contexts, volute springs find application in clutch mechanisms of heavy trucks, where they deliver precise engagement force and vibration damping to support high-torque transmissions. In off-road vehicles, particularly military designs from the 1940s, vertical volute spring suspension (VVSS) systems were adopted for superior shock absorption over rugged terrain, as seen in scout cars and half-tracks with capacities supporting 50-100 kN per axle assembly.[43] For example, the M3 half-track utilized vertical volute springs in its rear suspension to manage tracked propulsion loads during World War II operations. In aerospace transportation, volute springs serve as launch restraints in satellite deployables, with designs tested in 2022 for vibration isolation during rocket ascent to protect sensitive components.[37] Specific adaptations enhance their suitability for these vibrating environments, such as using oil-tempered steel for improved fatigue resistance and durability under cyclic stresses.[44] Additionally, integration with hydraulic dampers in automotive suspensions enables progressive ride control, where the volute's variable rate complements damping to optimize handling and comfort across load variations.[45]Industrial and Specialized Uses

Volute springs are widely employed in heavy machinery clutches and couplings, where their robust design supports substantial loads up to 500 kN while maintaining stability under high compression.[46] Horizontal volute springs, in particular, facilitate gripping actions in clamps by delivering precise, space-efficient force in applications requiring secure workpiece retention.[21] In hand tools and gardening devices, volute springs provide the essential cutting force in secateurs, enabling clean and efficient pruning of branches and stems. Their conical structure ensures consistent pressure without coil buckling, making them ideal for repetitive, high-cycle operations in such equipment.[9] For specialized applications, volute springs have been tested for use in satellite deployable mechanisms, with HEGONG conducting evaluations in 2022 to verify their performance in launch restraint assemblies that secure and release components in orbit.[37] These springs offer reliable energy storage and release in vacuum conditions, contributing to the precise deployment of antennas and solar arrays.[1] Adaptations of volute springs enhance their versatility in demanding settings; stainless steel variants provide superior resistance to corrosion in harsh industrial environments, such as chemical processing or marine-exposed machinery.[24] Custom configurations, including tailored geometries for variable load rates, are designed for specialized tooling to achieve progressive deflection suited to dynamic gripping or buffering tasks.[47]Advantages and Limitations

Key Advantages

Volute springs offer a compact design that enables high load capacities, typically handling forces from 100 to 500 kN in compact dimensions, making them suitable for space-constrained applications.[46][8] This configuration provides 2-3 times the energy density of traditional helical springs due to the nested coil structure, which maximizes energy storage and release efficiency in a smaller volume.[48] The conical geometry of volute springs enhances lateral stability by self-centering the load, as the overlapping coils guide each other radially during compression, significantly reducing the risk of buckling under off-axis forces.[9] This inherent stability eliminates the need for additional guides or supports, simplifying assembly and improving reliability in dynamic environments.[8] Volute springs exhibit progressive loading characteristics, where the spring rate increases with deflection as coils sequentially contact, providing softer initial response followed by stiffer resistance—ideal for controlled shock absorption.[48] They demonstrate strong fatigue durability derived from their tensile mechanics. Additional benefits include vibration damping through inter-coil friction, which dissipates energy effectively during operation.[22] Once tooling is established, volute springs are cost-effective for high-volume production due to efficient flat-strip forming processes.[46]Limitations and Challenges

Volute springs present several design and operational constraints that limit their applicability in certain scenarios. Manufacturing these springs requires specialized processes, such as cold winding for smaller sizes using pretempered or annealed carbon or stainless steel strips, and hot winding for larger sizes from carbon or low-alloy steels, which demand precise control to achieve the conical shape and overlapping coils. This complexity, including the need for custom tooling and limited availability of capable vendors, results in significantly higher production costs compared to helical compression springs, often making volute springs less economical for high-volume or standard applications.[49][1] The deflection characteristics of volute springs are inherently nonlinear, with the load-deflection curve transitioning to an increasing rate as coils progressively bottom out, which can restrict the usable travel range and pose risks of over-compression or bottoming out in applications requiring extended stroke. Additionally, stress distribution is nonuniform, with higher tensile stresses occurring at the inner coils due to the geometry and torsion, potentially up to 1.5 times the mean stress in certain configurations, which reduces fatigue life in high-cycle environments unless mitigated by treatments like peening. Intercoil friction during compression exacerbates this by causing galling and localized stress concentrations, further compromising durability in dynamic uses.[49][50] Volute springs are also sensitive to misalignment, as improper end configurations can lead to instability, canting, and uneven wear across coils, accelerating failure under load. Scalability poses further challenges; while thicknesses can range from less than 1 mm for small precision components, achieving very small overall dimensions (<1 mm) is difficult due to winding precision limits, and ultra-large sizes (>500 mm in height or diameter) require extensive hot forming that compromises accuracy and increases costs. These factors make volute springs less suitable for extreme size ranges compared to more versatile helical designs.[1][8]References

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Buffers_with_volute_springs_at_the_National_Railway_Museum