Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

The W58 was an American thermonuclear warhead used on the Polaris A-3 submarine-launched ballistic missile. Three W58 warheads were fitted as multiple warheads on each Polaris A-3 missile.[2]

Key Information

The W58 was 15.6 inches (400 mm) in diameter and 40.3 inches (1,020 mm) long, and weighed 257 pounds (117 kg). The yield was 200 kilotonnes of TNT (840 TJ).[1] The warhead used the Kinglet primary, which it shared with the W55 and W47 warheads.[3]

The W58 design entered service in 1964 and the last models were retired in 1982 with the last Polaris missiles.[1]

History

[edit]The W58 program began in mid-1959 when concerns were raised that enemy defensive capability was increasing due to improved detection capabilities. A study into the problem was conducted and its report released in August 1959 which recommended the development of a cluster warhead system for missile. In November 1959, a follow-up study into the feasibility of a cluster warhead for the Polaris missile began and its report was submitted in January 1960.[4] The report recommended the development of a missile carrying three warheads, mounted on an ejection system to disperse the warheads. The warheads would be released at approximately 200,000 feet (61,000 m) altitude. A protective fairing would protect the warheads during the underwater launch and early flight of the missile.[5]

Two reentry bodies were initially considered. Both were the same basic, slightly flared cylinder, but one had a hemispherical nose made of pyrolytic graphite, and the other an elliptical nose made of either pyrolytic graphite or beryllium. Both designs had an inner wall temperature of 1,500 °F (820 °C) with insulation limiting the warhead temperature to 300 °F (149 °C). A hemispherical shape was eventually chosen.[5]

In July 1960, it was decided that both airburst and surfaceburst fuzing would be provided. Airburst fuzing would be the inertial type, consisting of a range-corrected timer started by a decelerometer. The airburst fuze would be suitable for 95% of the target types envisioned for Polaris, while the remaining targets would be at too high an altitude for the airburst fuze and instead would be destroyed using the surfaceburst fuze. The ability to select surface burst for any target was also included.[5]

The primary safing device was to be a decelerometer that required 10 g (98 m/s2) deceleration for five seconds to actuate. An interlock device to prevent arming of the warhead if it did not separate from the missile was also included. The thermal battery that supplied power to the weapon was designed to actuate when exposed to reentry heating.[6]

Formal approval to develop the warhead was given in July 1960 and the military characteristics approved in August of that year. Lawrence Radiation Laboratory (now Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory) was assigned the warhead, and while the lab's workload was quite heavy at the time, it was believed that the four year development program envisaged (as opposed to the originally envisaged three-year program) would mean that compensatory reductions in other programs would not be needed.[6]

The nomenclature of XW-59 was initially assigned to the weapon, but in October 1960 the weapon was reassigned the nomenclature XW-58 (The XW-58 nomenclature was initially assigned to the Special Atomic Demolition Munition version of the W54 warhead).[7][8] The department of defense was responsible for all aspects of the weapon except for the warhead itself. Lockheed Missiles and Space Division were assigned development of the reentry body, missile and testing equipment, while the Naval Ordnance Laboratory developed the fuzing and firing system. A flight test program consisting of 14 tests was scheduled for October 1962. Early production was planned for January 1964, with a planned operational availability date of June 1964.[9]

The fuzing system would contain a barometric airburst fuze with three height of burst options, and a surfaceburst fuze. The firing system would be of the explosive-electric transducer type, the warhead would be sealed, and the boosting gas reservoir would be contained in a well that allowed for removal and replacement without breaking the warhead seal.[9] Magnesium instead of titanium was selected for the support casing in March 1961 as it offered minimum weight, ease of machining and moderate resistance to high temperatures. A protective can for the radiation case was provided as no means of sufficiently protecting the radiation case from the environment was known. The explosive-electric transducer was later substituted for a ferromagnetic transducer as the technology had not yet sufficiently advanced.[10]

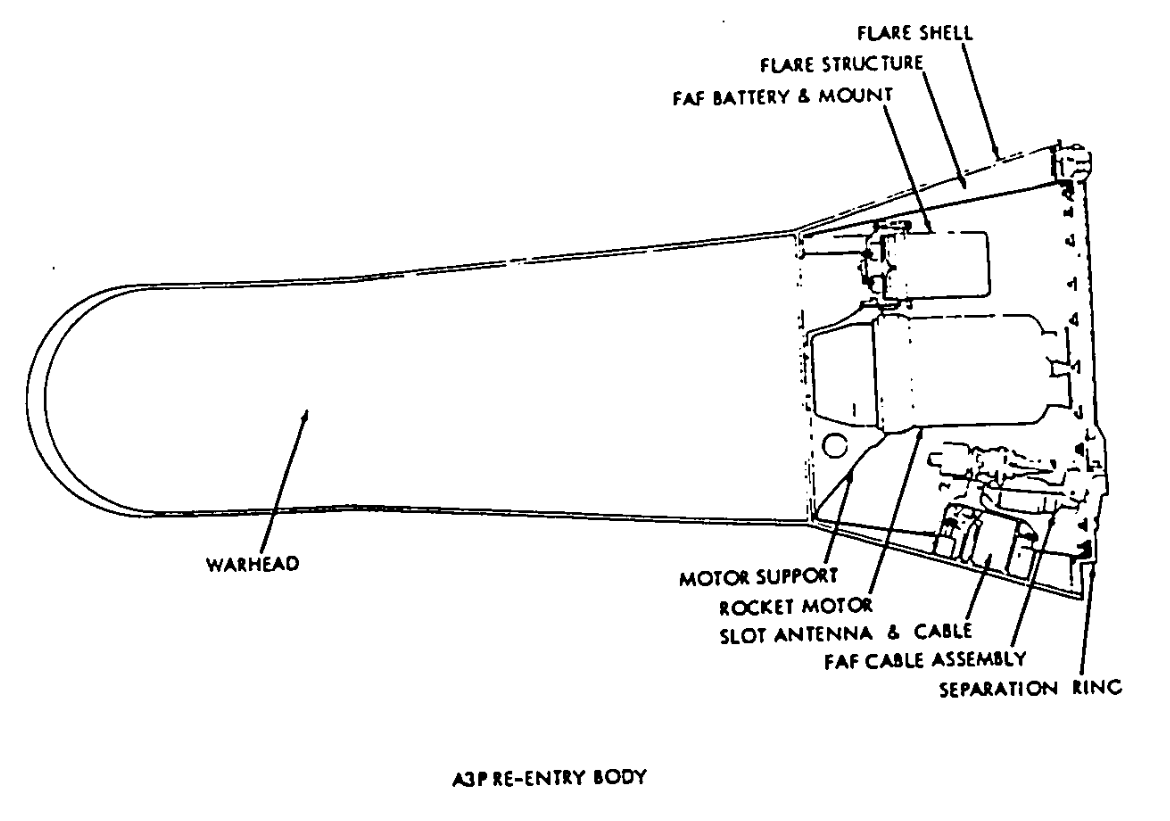

In August 1961, the proposed ordnance characteristics of the warhead were found to be satisfactory to the Navy.[11] The warhead with reentry body was 23.5 inches (600 mm) wide at the flare, 54 inches (1,400 mm) long and weighed 300 pounds (140 kg). The weapon consisted of a warhead, integrated fuzing and firing system and an outer heat shield surrounding the weapon. The planned pyrolytic graphite was substituted for an ablative heat shield integrated into the warhead structure.[12] The reentry body was known as the Mark 2.[13]

In March 1962, a warhead redesign occurred, leading to the redesigned warhead nomenclature of XW-58-X1. This redesign included close integration of warhead components, including integration of warhead casing with the heat shield and consolidation of the fuzing and firing system into a single unit. This redesign caused the design release date to slip by three months.[14] The Mk 58 Mod 0 was designed released in May 1963, with the exception of the reentry body and primary stage.[15]

In June 1963, the primary stage was replaced following an interim review. The new primary eliminated the mechanical safing system which the navy had expressed vulnerability concerns about.[15][16] Early production of the Mk 58 Mod 1 warhead began in March 1964 and the first submarine equipped with the warheads was on station in October 1964.[17]

The Mk 58 Mod 2 was proposed in December 1965 to provide resistance to high energy x-rays, but the program was never authorized.[17]

In approximately 1975, corrosion problems were discovered in some W58 warheads. The problem was evaluated with computer modelling rather than nuclear testing. The modelling determined that the problem could be overcome with some minor changes to weapon maintenance. However, the actions taken may have been influenced by the planned retirement date for the weapon.[18]

The warhead was retired in April 1982.[1]

Design

[edit]The final warhead consisted of a magnesium case with an aluminium cover. The nylon-phenolic heat shield was bonded to the magnesium case. The warhead cover included two ports for target detecting radar antennas, a baroport for pressure information and a valve to fill the warhead with dry air. The fuze was a single-channel device. The thermal battery and radar antennas were mounted on the warhead flare section. Airburst fuzing was controlled by a timer and baroswitch, with three height of burst options, while surfaceburst fuzing was provided by an electronic radiating type device.[19]

The firing set was of the dual-channel type and the weapon used an external neutron generator.[19] The nuclear system was designed to produce no more than 4 pounds (1.8 kg) yield in the event of a detonation by anything other than the firing system.[7] The safing system included acceleration actuated contacts that closed approximately 55 seconds after launch, at an altitude of 65,000 feet (20,000 m), which connected the warhead electrical system to the thermal battery and programmer.[20]

The warhead used the Kinglet nuclear primary.[16] Weapon yield was 200 kilotonnes of TNT (840 TJ).[1]

The warhead with reentry body was 23.5 inches (600 mm) wide at the flare, 54 inches (1,400 mm) long and weighed 300 pounds (140 kg).[12] The warhead without RB was 15.6 inches (400 mm) in diameter and 40.3 inches (1,020 mm) long, and weighed 257 pounds (117 kg).[1]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Sublette, Carey (12 June 2020). "Complete List of All U.S. Nuclear Weapons". Nuclear Weapon Archive. Archived from the original on 2009-02-27. Retrieved 2021-03-18.

- ^ History of the Mk 58 Warhead (Report). Sandia National Laboratory. February 1968. p. 5-6. SC-M-68-50. Archived from the original on 2022-06-12.

- ^ Hansen, Chuck (2007). Swords of Armageddon - Volume V. Chukelea Publications. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-9791915-5-8.

- ^ History of the Mk 58 Warhead, p. 3, 5.

- ^ a b c History of the Mk 58 Warhead, p. 6.

- ^ a b History of the Mk 58 Warhead, p. 7.

- ^ a b History of the Mk 58 Warhead, p. 8.

- ^ History of the Mk 54 Weapon (Report). Sandia National Labs. February 1968. p. 18. Archived from the original on 2021-05-22. Retrieved 2021-03-24.

- ^ a b History of the Mk 58 Warhead, p. 9.

- ^ History of the Mk 58 Warhead, p. 10.

- ^ History of the Mk 58 Warhead, p. 10-11.

- ^ a b History of the Mk 58 Warhead, p. 11.

- ^ Hansen, Chuck (2007). Swords of Armageddon - Volume VII. Chukelea Publications. p. 455. ISBN 978-0-9791915-7-2.

- ^ History of the Mk 58 Warhead, p. 11-12.

- ^ a b History of the Mk 58 Warhead, p. 13.

- ^ a b Swords of Armageddon - Volume VII, p. 455.

- ^ a b History of the Mk 58 Warhead, p. 4.

- ^ Swords of Armageddon - Volume VII, p. 458.

- ^ a b History of the Mk 58 Warhead, p. 16-17.

- ^ History of the Mk 58 Warhead, p. 14.

Development and History

Origins in Polaris Program

The Polaris program originated in the mid-1950s amid heightened Cold War tensions, as the United States recognized the vulnerability of land-based nuclear forces to Soviet preemptive strikes following advancements like the R-7 ICBM and Sputnik launch in 1957, prompting a push for a concealed, sea-based second-strike deterrent.[3] The U.S. Navy's Special Projects Office, established in 1955, formalized the program in December 1956 with initial contracts awarded for a solid-fueled submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) to ensure rapid development and deployment of a survivable nuclear triad leg.[4] This initiative addressed the strategic imperative for missiles that could be hidden underwater, evading detection and enabling retaliation even after a Soviet first strike, contrasting with fixed silo-based systems.[5] The W58 thermonuclear warhead emerged as an evolution within the Polaris framework to equip the A-3 variant, building on the earlier W47 warhead used for Polaris A-1 and A-2 missiles deployed from 1960 onward.[6] Development of the W58, led by Los Alamos National Laboratory, commenced around 1960 to enable a multiple independently targetable reentry vehicle (MIRV)-like configuration with three reentry vehicles per missile, enhancing penetration against Soviet air defenses and countering improvements in enemy detection capabilities.[7] This upgrade supported the Polaris A-3's extended range of approximately 2,500 nautical miles and first submerged submarine launch in October 1963, marking a shift toward more flexible and hardened delivery systems amid ongoing Soviet ICBM proliferation.[8] Production of the W58 began in March 1964, with initial deployment on A-3 missiles by 1964 to bolster the fleet ballistic missile force's effectiveness.[7]Design and Testing Phase

The W58 warhead's design emphasized a lightweight two-stage thermonuclear configuration to achieve a nominal yield of 200 kilotons while fitting within the mass and volume constraints of the Polaris A-3 missile's multiple reentry vehicles. Developed primarily by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, the primary stage utilized the Kinglet implosion system, shared with other contemporary warheads, to initiate fusion in the secondary stage, optimizing for a high yield-to-weight ratio essential for submarine-launched ballistic missile applications. This iterative engineering process prioritized empirical validation of fission-fusion coupling efficiency and structural integrity under launch and reentry stresses. Key testing occurred during Operation Dominic in 1962, with the Truckee shot on June 9 serving as the inaugural full-yield demonstration of the XW-58 prototype. Dropped from a B-52 aircraft at approximately 6,970 feet over the Pacific near Christmas Island, the device detonated at 210 kilotons, closely aligning with design expectations and verifying the warhead's boost and thermonuclear performance under simulated delivery conditions. The test confirmed reliable primary initiation and secondary compression, providing data that affirmed the design's suitability for clustered deployment.[9] Post-Truckee analysis identified minor discrepancies in reentry heating profiles and arming sequence timing, prompting refinements through laboratory simulations and non-nuclear component trials by 1963-1964. These adjustments enhanced thermal protection and safety interlocks without requiring additional full-yield detonations, culminating in the warhead's certification for production. Empirical data from the Dominic series underscored the W58's projected reliability, estimated at around 80 percent based on test outcomes and modeling.[10]Production and Initial Deployment

Production of the W58 warhead commenced in March 1964, enabling rapid integration with the Polaris A-3 submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM).[7] Manufacturing efforts were led by facilities associated with Sandia National Laboratories for engineering and quality assurance, building on designs from Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory to meet stringent SLBM requirements.[4] This scale-up addressed the need for compact, reliable thermonuclear devices capable of withstanding submarine launch conditions, including high pressure and vibration.[11] Initial deployment began in September 1964, when the USS Daniel Webster (SSBN-626), a Lafayette-class submarine, embarked on its first deterrent patrol carrying 16 Polaris A-3 missiles, each equipped with three W58 warheads in a multiple reentry vehicle configuration.[12] By 1965, the system achieved full operational capability across additional Lafayette-class SSBNs, reflecting successful overcoming of supply chain logistics for critical components such as plutonium pits and tritium boosters, which were produced in limited quantities from nuclear reactors.[13] This swift transition from prototype to fleet-wide service underscored advancements in production engineering, ensuring compatibility with submerged launch tubes and maintaining warhead integrity under maritime constraints.[14]Technical Design

Physics Package and Yield

The W58 physics package featured a two-stage thermonuclear configuration, with a boosted fission primary stage utilizing the Kinglet design and a fusion secondary stage to achieve a nominal yield of 200 kilotons TNT equivalent.[15][16] This yield resulted from radiation implosion, where X-rays from the primary compressed the secondary, enabling deuterium-tritium fusion reactions that released high-energy neutrons to enhance fission efficiency in both stages.[17] The design emphasized compactness, with the package measuring 15.6 inches in diameter and 40.3 inches in length, while weighing approximately 257 pounds.[18] Key materials included lithium deuteride as the primary fusion fuel in the secondary stage, which upon compression and heating produced tritium in situ via neutron-lithium-6 interactions to sustain the fusion chain.[19] A beryllium neutron reflector surrounded the primary's fissile core, minimizing neutron loss and enabling the small size without sacrificing critical mass efficiency.[19] This reflector, combined with deuterium-tritium gas boosting in the primary, optimized neutron economy, allowing the overall package to deliver high yield-to-weight performance of roughly 1.47 kilotons per kilogram.[18] Declassified test data from the early 1960s, including shots validating the Kinglet primary's integration, demonstrated yield consistency with minimal variability across prototypes, attributable to precise engineering of compression dynamics and material purity.[20] No significant deviations were reported in production units, reflecting robust first-principles modeling of neutron transport and hydrodynamic stability under detonation conditions.[21]Reentry Vehicle Integration

The W58 warhead was integrated into the Mark 2 reentry vehicle for use on the Polaris A-3 submarine-launched ballistic missile, enabling multiple reentry vehicle (MRV) deployment. Each Mark 2 reentry vehicle encased a single W58 warhead weighing 257 pounds (117 kg), a lightweight design that facilitated the carriage of three such units per missile while contributing to the overall payload efficiency.[12] This mass reduction, achieved through advanced materials, allowed the Polaris A-3 to extend its range to 2,500 nautical miles compared to prior variants by optimizing the boost phase trajectory and reducing payload weight.[12] The reentry vehicle's ablative heat shield, constructed from nylon-phenolic composite material, protected the warhead during atmospheric reentry at hypersonic speeds exceeding Mach 15. The ablative process involves the controlled erosion and pyrolysis of the shield's outer layers, which absorbs and dissipates thermal energy through mass loss and vaporization, preventing structural failure from peak heating rates.[22] This engineering choice directly enhanced survivability by maintaining warhead integrity against aero-thermal stresses, linking material ablation efficiency to reliable terminal performance. Spin-stabilization imparted to the Mark 2 reentry vehicle during post-boost phase dispensing improved accuracy by providing gyroscopic rigidity against atmospheric perturbations, thereby reducing trajectory dispersion and circular error probable (CEP). The Polaris A-3's post-boost vehicle served as a dispenser, releasing three Mark 2 reentry vehicles in a patterned deployment for MRV operation, which prioritized area saturation over precise independent targeting to counter early ballistic missile defenses.[12] This configuration causally tied reentry stability to strategic effectiveness, as stable trajectories minimized intercept vulnerability and supported doctrinal emphasis on assured penetration.Engineering Challenges and Innovations

The W58 warhead's design required overcoming severe miniaturization constraints to achieve compatibility with the Polaris A-3 submarine-launched ballistic missile's limited payload capacity, necessitating a lightweight physics package capable of reliable thermonuclear performance within a volume of approximately 0.6 cubic meters and a mass under 120 kilograms. Engineers at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory addressed these challenges through iterative full-scale testing during Operation Dominic in 1962, which certified advanced implosion systems for uniform compression despite reduced component scales, marking a pivotal advancement in compact warhead technology essential for sea-based deterrence.[23] Key innovations included the incorporation of thorium-based radiation cases in the secondary stage to optimize neutronics and reduce overall weight without compromising energy output, a technique validated in subsequent proof tests around 1968 that enhanced efficiency over prior designs.[24] Reliability concerns emerged post-deployment, with early prototypes exhibiting corrosion in internal components that threatened implosion symmetry; these were mitigated via non-nuclear computer simulations by the mid-1970s, demonstrating predictive modeling's efficacy in sustaining over 90% confidence levels without explosive trials.[20][23] This empirical approach prioritized causal fixes from diagnostic data, predating widespread adoption of such methods in stockpile stewardship.Specifications and Performance

Physical Dimensions and Weight

The W58 thermonuclear warhead had a length of 40.3 inches (1,020 mm) and a diameter of 15.6 inches (400 mm), with a total weight of 257 pounds (117 kg).[25][26] These dimensions were optimized for integration into the Mk 2 reentry vehicle, ensuring compatibility with the Polaris A-3 submarine-launched ballistic missile's payload constraints.[27] This design achieved a substantial reduction in mass compared to the earlier W47 warhead for Polaris A-1 and A-2 missiles, which weighed approximately 600 pounds (272 kg), enabling the accommodation of three W58 warheads in a MIRV configuration while preserving the missile's operational range.[28][17] Production specifications remained uniform across the approximately 550 units manufactured from 1964 to 1967, facilitating reliable interchangeability and maintenance within the U.S. Navy's strategic arsenal.[7]Yield and Delivery Capabilities

The W58 thermonuclear warhead possessed a nominal explosive yield of 200 kilotons TNT equivalent, developed by the Los Alamos National Laboratory and optimized for high-efficiency fission-fusion processes within its compact physics package.[1] This yield was fixed but supported selectable fuzing modes, including airburst for maximizing blast and thermal effects over area targets or contact burst for hardened point targets, as verified through underground nuclear tests conducted in the early 1960s.[1] In delivery, the W58 was integrated into the Polaris A-3 submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) as a multiple independently targetable reentry vehicle (MIRV) configuration, with three warheads per missile enabling dispersed targeting over ranges up to 4,600 kilometers.[12] The system's inertial guidance achieved a circular error probable (CEP) of approximately 900 meters (0.5 nautical miles) at maximum range, reflecting trajectory precision derived from post-boost vehicle dispersion and reentry vehicle stability tests.[12] The warhead's design incorporated robust encapsulation to withstand prolonged submersion in submarine launch tubes, including resistance to saltwater corrosion and pressure differentials encountered during patrol storage, ensuring integrity for extended deployments without compromising yield delivery.Reliability Metrics

Surveillance testing of the W58 warhead stockpile, conducted by the Department of Energy (DOE), identified chemical degradation issues such as corrosion in internal components during the late 1970s and early 1980s, which raised concerns about potential yield reduction but were addressed through non-nuclear corrective measures to restore confidence without requiring full-scale testing.[20][29] These interventions demonstrated the feasibility of maintaining warhead integrity via laboratory analysis and component replacement rather than explosive certification, countering notions of systemic unreliability in aging thermonuclear designs.[29] Robust safety features, including redundant safing mechanisms and multi-step arming sequences, minimized risks of unintended detonation throughout the W58's deployment from 1964 to its retirement around 1982; no accidental high-explosive detonations or fuzing malfunctions were recorded in handling, storage, or simulated launch environments during this period.[30] Tritium reservoirs, critical for boosting primary yield, were periodically exchanged under DOE maintenance protocols to counteract the isotope's 12.3-year half-life decay, ensuring sustained performance metrics in non-operational assessments.[14] Polaris A-3 flight tests integrating the W58 achieved successive successes in submerged launches by the early 1960s, with the missile variant demonstrating operational readiness through at least 13 consecutive underwater firings, underscoring the warhead-missile system's empirical dependability for strategic deterrence despite isolated stockpile anomalies.[31] Overall stockpile confidence for submarine-launched warheads like the W58 was sustained at levels sufficient for certification, as evidenced by continued deployment without evidence of degraded mission effectiveness in DOE evaluations.[20]Operational Deployment

Integration with Polaris A-3 SLBM

The W58 warhead was integrated into the Polaris A-3 submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) as part of a multiple reentry vehicle (MRV) configuration, with three warheads housed in Mk 2 reentry bodies deployed from a single post-boost vehicle.[32] This setup replaced the single reentry vehicle of earlier Polaris variants, enabling the missile to deliver warheads spaced to cover a target area for improved saturation effects against hardened or dispersed sites. The integration process involved mating the lightweight W58, weighing approximately 257 pounds each, to the missile's upper stage, ensuring compatibility with the solid-propellant motor's high-thrust profile and associated launch dynamics from submerged submarines.[33] Engineering adaptations for the solid-fuel rocket included reinforced mounting systems in the reentry vehicle to withstand the intense vibrations, rapid acceleration, and thermal stresses generated during the Polaris A-3's boost phase, which differed from liquid-fueled systems due to the instantaneous ignition of solid propellant grains.[34] These measures ensured warhead integrity during the missile's underwater encapsulation launch, where gas generators expelled the missile from the submarine tube before ignition, subjecting components to unique hydrodynamic and shock loads.[35] The first operational deployment of the Polaris A-3 with W58 MRVs occurred on September 28, 1964, aboard USS Daniel Webster (SSBN-626), following successful flight tests that validated reentry vehicle separation and trajectory dispersion.[32] Launch parameters specific to naval operations emphasized submerged firing to minimize detection, with the MRV system's fixed dispersion pattern—rather than independent targeting—optimized for overwhelming area defenses or bracketing primary targets with secondary warheads, marking a doctrinal evolution toward multiplicative strike capacity without full MIRV independence.[12] This configuration achieved a range of about 2,500 nautical miles while maintaining the missile's compact dimensions for submarine compatibility.[8]Submarine Fleet Utilization

The W58 warhead equipped Polaris A-3 submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) deployed on U.S. Navy fleet ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs), including Lafayette-class vessels and follow-on classes such as James Madison-class, with each submarine loading 16 missiles carrying three W58 warheads apiece for a total of 48 warheads per boat.[36][12] These assignments formed a core element of the sea-based leg of the U.S. nuclear triad, with approximately 10 SSBNs retaining Polaris A-3 configurations through the late 1970s due to structural limitations preventing conversion to larger Poseidon missiles.[37] SSBNs armed with W58-equipped Polaris A-3 missiles executed continuous at-sea deterrence patrols in the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans from 1964 onward, maintaining strategic ambiguity and survivability against preemptive strikes.[12][38] Atlantic patrols originated from bases like Charleston, South Carolina, and occasionally forward-deployed sites, while Pacific operations launched from Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, with patrol durations averaging 60-70 days to sustain round-the-clock alert postures.[37] This operational tempo ensured that a significant fraction of the fleet—typically one-third—was continuously on station, bolstering second-strike assurance amid Cold War tensions.[37] Logistical sustainment emphasized periodic refits every three to five years for warhead certification, missile handling, and subsystem overhauls, minimizing downtime while upholding stringent safety and reliability standards.[39] These cycles, integrated into the dual-crew (Blue-Gold) rotation model, yielded Polaris system readiness rates exceeding 90 percent, reflecting robust maintenance protocols and minimal failure incidents during patrols.[39][37]Strategic Employment Doctrine

The strategic employment doctrine for W58 warheads integrated into Polaris A-3 submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) prioritized counterforce operations against Soviet military assets, including ICBM silos and command centers, to degrade enemy nuclear warfighting potential in a first or second strike. This approach aligned with evolving U.S. nuclear planning under the Single Integrated Operational Plan (SIOP), which assigned Polaris forces to strike hardened targets such as radar installations and launch facilities, leveraging the warhead's 200-kiloton yield and multiple independently targeted reentry vehicle (MIRV) dispersion for enhanced kill probabilities against dispersed or reinforced sites.[40][41] A fallback assured destruction posture retained the capacity to devastate Soviet urban-industrial infrastructure, ensuring retaliatory devastation even if counterforce aims were partially frustrated by defenses or preemption.[42] Operational alert postures emphasized continuous deterrence through submerged patrols by fleet ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs), with approximately one-third of the force at sea at any time to maintain invulnerability to preemptive attack and enable prompt launch-on-warning or riding-out-the-storm responses.[43] The W58's design, featuring three warheads per missile patterned in a triangular footprint over a single aim point, optimized coverage for hardened targets requiring overpressure exceeding 2,000 psi, thereby supporting doctrinal shifts toward selective counterforce options by the mid-1960s without compromising sea-based second-strike reliability.[44] Patrol durations typically spanned 60-90 days, with submarines operating in designated ocean areas to evade Soviet antisubmarine warfare while preserving launch readiness.[45] This doctrine's efficacy manifested in the empirical outcome of mutual deterrence, wherein neither superpower initiated nuclear conflict despite crises such as the Cuban Missile Crisis and Berlin standoffs, attributable to the credible threat of SLBM retaliation disrupting Soviet command structures and reserves.[46] The non-employment of W58-armed systems throughout their service life (1964-1982) underscored the stabilizing dynamics of survivable sea-based forces in counterbalancing land-vulnerable Soviet ICBMs.[6]Strategic Role and Impact

Role in Nuclear Deterrence

The deployment of the W58 warhead on the Polaris A-3 submarine-launched ballistic missile in 1964 significantly bolstered the United States' second-strike nuclear capabilities, providing a survivable retaliatory force that Soviet planners could not confidently preempt in a first strike.[47] Submerged ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) armed with W58-equipped missiles operated covertly in ocean patrols, rendering them largely immune to preemptive detection and targeting compared to fixed land-based silos or vulnerable bombers, thereby enhancing the credibility of mutual assured destruction (MAD) as a deterrent framework.[48] This capability complicated Soviet calculations for a disarming first strike, as the assured survival of even a fraction of the U.S. SSBN fleet—potentially delivering hundreds of W58 warheads—guaranteed catastrophic retaliation.[49] As the sea-based leg of the U.S. nuclear triad, the W58 contributed to a diversified deterrent posture that mitigated risks inherent to any single delivery mode, ensuring redundancy against technological surprises or intelligence failures by adversaries.[48] The invulnerability of submerged SSBNs complemented intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and strategic bombers, creating a layered system where the Polaris A-3's range of approximately 2,500 nautical miles and multiple reentry vehicles per missile amplified the overall threat of assured retaliation without relying on vulnerable forward bases.[8] This triad structure, fortified by W58 deployments on expanding SSBN fleets, underpinned U.S. strategic stability during the 1960s and 1970s, as evidenced by the absence of nuclear escalation despite crises like the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis and subsequent proxy conflicts. Soviet responses to the U.S. SLBM buildup, including Polaris A-3 with W58, involved accelerated development of their own submarine-launched systems, such as the R-27 (SS-N-6) missile on Yankee-class SSBNs, and enhanced antisubmarine warfare (ASW) capabilities to contest American sea-based forces, yet these measures did not precipitate direct nuclear confrontation.[50] Rather than risking hot war, the USSR pursued symmetric buildup and arms control negotiations, such as the 1972 Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT I), reflecting the stabilizing influence of reciprocal second-strike vulnerabilities introduced by deployments like the W58.[51] The lack of nuclear war throughout the Cold War, despite intense ideological rivalry and multiple near-misses, supports the inference that enhanced deterrence credibility from sea-based systems, including those armed with W58, contributed to crisis stability by raising the perceived costs of aggression beyond tolerable thresholds for both superpowers.[52]Advancements in MIRV Technology

The W58 warhead, developed by the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and first deployed in September 1964 aboard the USS Thomas Jefferson, enabled the Polaris A-3 SLBM to carry three warheads in a multiple reentry vehicle (MRV) configuration using the Mk 2 reentry body.[53] Each W58 had a yield of 200 kilotons and a weight of approximately 257 pounds, representing a miniaturization advance that allowed multiple deployment within the missile's volume constraints without sacrificing destructive power.[54] This MRV system dispersed the warheads in a pre-set pattern to cover larger target areas, such as bomber bases, overcoming the single-warhead limitations of earlier Polaris variants in addressing dispersed threats.[53] Engineering innovations in the W58 and Mk 2, including reliable separation mechanisms and aerodynamic stability during reentry, provided foundational technologies for subsequent MIRV systems.[55] Declassified analyses indicate that MRV experience informed the development of post-boost vehicles capable of maneuvering to release independently targetable reentry vehicles (RVs), enhancing accuracy through differential velocity adjustments.[56] These advancements addressed vulnerabilities in fixed-trajectory systems, enabling SLBMs to engage multiple hardened or separated targets more effectively. The W58's legacy extended to the Poseidon C-3 program, operational from 1971, where lessons in warhead integration and RV dispersion contributed to a true MIRV bus deploying up to 10 W68 warheads of 40-50 kilotons each.[57] This progression allowed for precision-matched yields against specific targets, minimizing overkill and associated collateral effects compared to singular high-yield detonations, as MIRVs could allocate lower-yield options to softer infrastructure while reserving capacity for reinforced sites.[56][53]Geopolitical Influence During Cold War

The W58 warhead, paired with the Polaris A-3 submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) and operational from September 1964, bolstered U.S. second-strike capabilities by enabling three 200-kiloton warheads per missile, delivered from stealthy submarines that evaded preemptive Soviet attacks. This configuration addressed vulnerabilities exposed in the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, where Soviet leaders recognized the superiority of U.S. Polaris forces over their land-based systems, reinforcing mutual assured destruction (MAD) as a stabilizing doctrine. By providing assured retaliation independent of fixed silos, the W58-equipped fleet deterred escalation in subsequent crises, such as the 1967 Six-Day War and 1973 Yom Kippur War, where U.S. nuclear readiness signaled resolve without direct invocation.[58][59] Soviet deployment of Yankee-class submarines with SS-N-6 (R-27) SLBMs in June 1967 prompted U.S. reliance on the W58's multiple reentry vehicle (MRV) system to preserve a qualitative edge, as Soviet missiles initially carried single warheads and lagged in submarine quieting and accuracy until the 1970s. The W58's design allowed one launcher to deliver payloads equivalent to three separate strikes, complicating Soviet countermeasures and maintaining U.S. superiority in at-sea warhead numbers—approximately 600 by 1970 across 31 submarines—over the USSR's fewer, noisier platforms. This asymmetry underscored realist deterrence, prioritizing verifiable survivability over numerical parity illusions.[6][50] In the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT I), concluded with the May 1972 Interim Agreement, W58-armed Polaris A-3 missiles influenced bargaining by highlighting U.S. MIRV precursors, which the treaty's launcher caps (e.g., 710 U.S. SLBMs) did not constrain, enabling warhead proliferation without violation. Soviet proposals for warhead limits failed amid U.S. insistence on counting delivery vehicles, as MIRV advantages deterred concessions that could erode the sea-based edge; the accord froze Soviet gains while preserving U.S. flexibility, stabilizing escalation risks without favoring disarmament over deterrence.[60][61]Controversies and Criticisms

Safety and Arming Mechanisms

The W58 warhead incorporated a one-point safe design, ensuring that detonation of the high explosive components at any single point would produce no nuclear yield exceeding four pounds of TNT equivalent, thereby minimizing risks from accidental partial explosions.[30] This feature, standard in U.S. thermonuclear warheads by the mid-1960s, relied on symmetric implosion geometry and insensitive high explosives to prevent unintended chain reactions in the primary stage.[62] Arming mechanisms employed environmental sensing devices, including acceleration-actuated contacts that remained open until specific launch profiles were detected, typically closing about 55 seconds post-launch at altitudes around 65,000 feet to enable subsequent reentry and impact sequencing.[63] These systems prevented premature arming during storage, transport, or early flight phases, requiring a sequence of velocity, altitude, and spin inputs for full activation, thus isolating firing circuits until post-boost conditions were verified. Permissive action links, mandated by NSAM-160 in 1962 and implemented on SLBM warheads like the W58 by its 1964 deployment, added electronic codes to preclude unauthorized arming, though early variants emphasized command-disable over full PAL until upgrades.[47] No accidental nuclear detonations have occurred with the W58 across its service life from 1964 to 1982, despite over 1,450 units produced and deployed on Polaris A-3 submarines; this empirical record underscores the efficacy of integrated safing features against handling errors or environmental stressors.[62] A noted corrosion issue in W58 components, identified during stockpile surveillance, was mitigated through non-nuclear testing and targeted maintenance protocols without compromising operational safety or leading to yield risks. Critics highlight inherent hazards in tritium boosting systems, such as potential leakage during disassembly or accidents, given tritium's beta emissions and biological uptake risks, yet no W58-specific incidents of tritium release or criticality have been documented, prioritizing observed zero-failure outcomes over hypothetical concerns.[65] Proponents of the design emphasize these mechanisms' role in elevating safety margins beyond earlier fission weapons, with one-point safety and environmental qualifiers reducing accidental yield probabilities to negligible levels under Department of Defense standards. Opponents, often from arms control perspectives, argue that tritium's 12-year half-life and handling demands introduce unavoidable proliferation and maintenance vulnerabilities, though data from decades of submarine patrols refute claims of systemic unreliability by showing no inadvertent arming or detonation events.[30]Cost and Resource Allocation Debates

The W58 warhead program, integrated into the Polaris A-3 missile, exemplified efficient resource management amid 1960s fiscal constraints, with production spanning March 1964 to June 1967 without reported major overruns typical of parallel initiatives like certain manned bomber upgrades.[7] This timeline reflected streamlined scaling at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, prioritizing rapid deployment over expansive R&D expansions, contrasting with later programs such as the B-1 bomber that ballooned beyond initial budgets.[34] Critics, including pacifist organizations like the Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy, contended that allocations for warheads like the W58 diverted resources from pressing domestic needs, estimating opportunity costs in billions that could fund anti-poverty efforts or infrastructure amid rising Vietnam War expenditures.[66] Such arguments, often amplified in congressional hearings, framed nuclear spending as exacerbating inequality, with proponents of reallocation citing the era's $700 billion defense outlays (in then-year dollars) as evidence of misplaced priorities over social welfare.[67] Defenders, drawing from strategic analyses, emphasized deterrence's long-term fiscal returns, asserting that credible SLBM capabilities forestalled superpower confrontations whose economic toll—projected in models exceeding World War II's inflation-adjusted $4 trillion—far outstripped development investments.[66] This perspective, echoed in Navy doctrinal reviews, positioned the W58's role in assured second-strike as a high-ROI hedge against escalation, validated by the absence of direct U.S.-Soviet conflict through the Cold War.[34] Empirical assessments of Polaris-era budgeting underscored this efficiency, with the overall SLBM thrust achieving operational readiness under initial projections, bolstering arguments against waste claims.[57]Proliferation and Arms Control Perspectives

The deployment of the Polaris A-3 submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) equipped with three W58 warheads in September 1964 marked an early U.S. advancement in multiple reentry vehicle (MRV) technology, enabling a single missile to deliver multiple 200-kiloton payloads against dispersed targets. This capability, while enhancing U.S. second-strike assurance, introduced significant challenges to arms control verification by obscuring the distinction between launcher counts and actual warhead numbers, as external observation could not reliably confirm the number of reentry vehicles per missile without intrusive inspections.[68][69] During the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT I), concluded in May 1972, the absence of MIRV-specific limits in the Interim Agreement allowed the U.S. to expand its strategic warhead inventory—reaching approximately 7,000 deliverable warheads by the mid-1970s—without violating launcher caps of 1,054 ICBMs and 710 SLBMs for the U.S., compared to higher Soviet allowances. Soviet negotiators viewed U.S. MRV/MIRV deployments, including on Polaris successors like Poseidon, as destabilizing escalations that prompted accelerated Soviet MIRV development on SS-N-8 SLBMs and SS-18 ICBMs, with the USSR conducting its first MIRV tests in response by 1968. This dynamic fueled mutual suspicions, as MIRVs facilitated counterforce targeting of silos and command centers, potentially incentivizing preemptive strikes if verification failed to ensure parity.[60][70][71] Proliferation hawks, such as those in the U.S. defense establishment, expressed concerns over the risks of technological leakage from MIRV programs like the W58, arguing that shared components or design principles could enable non-state actors or adversaries to replicate compact, high-yield warheads, though no verified incidents of W58-specific proliferation occurred. In contrast, arms control advocates pushed for MIRV bans or reductions in SALT II (signed June 1979), citing the technology's role in inflating arsenals beyond verifiable levels, but critics countered that such naive disarmament—without robust, on-site verification—would destabilize deterrence by exposing U.S. forces to unverifiable Soviet advantages. Empirical evidence from the era supports the deterrence argument: MIRV-equipped SLBMs like Polaris A-3 bolstered submarine survivability, ensuring retaliatory capacity even after a Soviet first strike, as submarine dispersal reduced vulnerability compared to fixed ICBMs, thereby stabilizing mutual assured destruction rather than enabling disarming attacks.[72][73][74] The United Kingdom's adaptation of Polaris A-3 technology under the 1962 Nassau Agreement involved U.S. provision of missiles and targeting systems, with Britain developing compatible MRV-capable warheads (ET.317) by 1968, but stringent bilateral safeguards prevented unauthorized transfer, averting direct proliferation risks tied to W58 designs. Overall, while doves emphasized MIRV-driven arms racing as a pathway to catastrophe, hawkish analyses highlighted how the technology's deployment from 1964 onward compelled Soviet restraint, as the unverifiable multiplication of U.S. warheads on mobile platforms deterred preemptive aggression by raising the costs of any attempted disarming strike.[75][70]Retirement and Legacy

Phase-Out and Dismantlement

The W58 warhead entered retirement in 1982, coinciding with the U.S. Navy's phase-out of the Polaris A-3 submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM), which it armed, in favor of the Poseidon C-3 SLBM carrying W68 warheads.[16] This transition reflected broader strategic upgrades rather than warhead-specific defects, as the Polaris system's limited range of approximately 2,500 nautical miles and three-warhead MIRV configuration yielded to Poseidon's extended reach exceeding 4,000 nautical miles and capacity for up to ten lower-yield reentry vehicles, enhancing penetration of defended targets and overall deterrence posture.[57] Dismantlement of the W58 stockpile proceeded at the Pantex Plant near Amarillo, Texas, the sole U.S. Department of Energy facility authorized for nuclear warhead disassembly, where retired units underwent sequential breakdown: high explosives were separated from the physics package, fissile components like plutonium pits were extracted for recycling or secure storage, and non-nuclear parts were demilitarized or disposed.[76] Plutonium from pits was processed for potential reuse in subsequent warhead designs, aligning with resource conservation practices amid the era's arms control emphases, though no treaties directly mandated W58 retirement.[77] By the mid-1980s, the entire W58 inventory—originally numbering around 1,200 units produced between 1960 and 1964—had been fully dismantled, eliminating it from active and reserve stockpiles as Poseidon deployment accelerated.[78] This process supported U.S. compliance with emerging strategic arms limitations, such as the unratified SALT II framework, by reducing older-generation assets without compromising capabilities through technological obsolescence alone.[47]Technological Lessons for Successors

The W58 warhead's compact thermonuclear design, delivering a 200-kiloton yield in a package weighing roughly 110 kilograms, pioneered miniaturization techniques essential for fitting multiple independent reentry vehicles onto submarine-launched ballistic missiles with volume constraints.[32] These methods, including optimized staging of fission primary and fusion secondary components, were iteratively refined in successor warheads such as the W76 (100-kiloton yield, approximately 43 kilograms) and W88 (475-kiloton yield, approximately 163 kilograms), enabling higher yields per unit volume on Trident I and II missiles while maintaining compatibility with reentry vehicle envelopes derived from Polaris-era constraints.[79] Reliability assessments for the W58 established standardized protocols for addressing age-related degradation without nuclear testing, notably resolving 1970s corrosive oxidation of internal parts through computational modeling and non-nuclear experiments.[20] This approach validated predictive simulation for material integrity and performance margins, directly informing life-extension programs for W76 and W88 warheads, where similar modeling ensures ongoing certification amid extended service lives beyond original design parameters.[29] Operational data from the W58-equipped Polaris A-3 MIRV bus, involving post-boost vehicle sequencing for three warheads, yielded causal insights into reentry vehicle dispersion and guidance corrections that enhanced subsequent designs.[55] These lessons contributed to Trident II D5 accuracy upgrades, including refined inertial navigation and bus stabilization, achieving a circular error probable of approximately 90 meters by 1990, a marked improvement over Polaris baselines through accumulated engineering refinements in trajectory predictability and error compensation.[80]Enduring Strategic Relevance

The deployment of the W58 warhead on the Polaris A-3 submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) in 1964 established sea-based multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs) as a cornerstone of U.S. nuclear deterrence, emphasizing survivable second-strike capabilities that remain integral to countering peer adversaries like Russia and China. This approach prioritized stealthy, dispersed launch platforms immune to preemptive strikes, a principle echoed in the current Ohio-class and forthcoming Columbia-class submarines armed with Trident II D5 missiles carrying MIRVed W76 and W88 warheads. As of 2023, the U.S. maintains approximately 1,000 SLBM warheads in its deployed strategic stockpile, underscoring the enduring validity of this posture amid Russia's modernization of Borei-class SSBNs with Bulava MIRVed SLBMs and China's expansion toward 600 warheads, including JL-3 SLBMs on Type 094 submarines.[81][82][83] The W58's compact thermonuclear design, achieving 200 kilotons yield in a 725-pound package suitable for three MIRVs per missile, validated lightweight high-yield warheads for SLBMs, influencing successors like the W88 and enabling greater payload flexibility without sacrificing submarine stealth or range. This feasibility demonstrated that thermonuclear primaries could be minimized for reentry vehicle efficiency, a legacy pertinent to addressing modern challenges such as hypersonic glide vehicles and advanced missile defenses, where MIRV salvoes overwhelm interceptors through saturation and independent targeting. U.S. strategic reviews affirm that such sea-based MIRV multiplicity enhances deterrence by complicating adversary counterforce targeting, preserving assured retaliation even against evolving threats.[23][84] Claims of obsolescence for SLBM MIRV strategies, often advanced by arms control advocates citing destabilizing first-strike incentives, are countered by the persistent U.S. reliance on these systems for strategic stability, as evidenced by the 2023 Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture recommending accelerated sea-based modernization to match Sino-Russian expansions. Unlike fixed ICBMs, SLBMs' underwater mobility renders MIRVing stabilizing rather than provocative, with no feasible near-term alternatives supplanting their role in extended deterrence. Recent Pentagon assessments, including calls to restore MIRVs on Minuteman III ICBMs for flexibility, further refute irrelevance narratives, affirming the W58-era model's adaptability in a multipolar nuclear environment.[82][85][70]References

- https://www.[jstor](/page/JSTOR).org/stable/2538803