Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

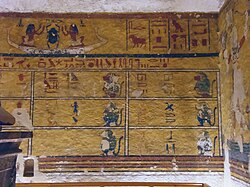

Tomb WV23, also known as KV23, was the burial place of Ay, a pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty, in the Western Valley of the Kings near modern-day Luxor. The tomb was discovered in 1816 by Giovanni Belzoni. Its architecture is similar to the royal tomb of Akhenaten at Amarna, with a straight descending corridor leading to a "well chamber" that has no shaft. This leads to the burial chamber, which contains the reconstructed sarcophagus, which was smashed in antiquity. The tomb was anciently desecrated, with many instances of Ay's image or name erased from the wall paintings. Its decoration is similar in content and colour to that of the tomb of Tutankhamun (KV62), with a few differences. On the eastern wall there is a depiction of a fishing and fowling scene, which is not shown in other royal tombs, normally appearing in burials of nobility.

Key Information

History

[edit]Burial

[edit]Ay ruled as pharaoh during the late Eighteenth Dynasty of the New Kingdom. He was a vizier under Tutankhamun, and later succeeded him as king.[1] Ay was likely an old man when he became king and only ruled for four years. He was buried in WV23, a tomb in the Western Valley of the Kings thought to have been originally intended for Tutankhamun.[2]

Ay's burial was a relatively modest affair as no trace was found of the canopic chest or its shrine, nor were any trace of faience or stone ushabti; also absent was any sign of the gilded burial shrines that presumably surrounded the sarcophagus. The Egyptologist Otto Schaden suggests that they may have been entirely removed or never placed in the tomb. The sarcophagus lid may never have been placed on the box. Instead, the sarcophagus may have been covered with a pall covered in gilded copper rosettes, as was found in the tomb of Tutankhamun.[3]

Ay's burial was likely vandalised in a sanctioned attack in the reigns of his successor Horemheb or the early Ramesside pharaohs, though Horemheb's treatment of Ay's monuments makes him the most likely culprit. At this time the sarcophagus was smashed, the names and images of Ay and Tey removed, and all the valuables thoroughly looted.[3] The contents of KV58 likely originated from WV23, as Ay's name occurs more frequently than that of Tutankhamun. They were either deposited there by robbers, or purposefully during the dismantling of the royal burials. Nicholas Reeves and Richard Wilkinson see this as support of the theory that the body of Ay was cached in KV57, the tomb of Horemheb, at that time.[4] Schaden considers that the body of Ay may be the rewrapped "yellow skeleton" interred with later mummies in WV25.[3]

Discovery

[edit]

In 1816, WV23 was discovered by chance by the Italian explorer Giovanni Belzoni.[5] After visiting WV22, the tomb of Amenhotep III, he moved further into the valley "to examine the various places where water descends from the desert into the valleys after rain"[5] and upon finding an isolated pile of stones, probed the depth with his cane. Finding that there was a deep void under the rocks, he hired workmen and returned the following day. The tomb proved to be just below the surface, and within two hours the entrance had been cleared. Belzoni considered the tomb a modest find:

I cannot boast of having made a great discovery in this tomb, though it contains several curious and singular painted figures on the walls; and from its extent, and part of a sarcophagus remaining in the centre of a large chamber, have reason to suppose, that it was the burial-place of some person of distinction.[5]

Later visitors

[edit]The tomb was visited by the early Egyptologist John Gardiner Wilkinson, who noted in his 1835 publication that the tomb "contains a broken sarcophagus and some bad fresco painting of peculiarly short and graceless proportions."[6] Karl Richard Lepsius visited the tomb in 1845 and noted too the destroyed sarcophagus and commented that Ay's name was "everywhere studiously erased, with the exception of a few traces on the walls, as well as upon the sarcophagus."[7] He also copied some of the wall paintings and made notes regarding the sarcophagus box. The sarcophagus, which had been damaged in antiquity not long after the burial of Ay, was deliberately damaged in the late nineteenth century and was subsequently moved to Egyptian Museum in Cairo before being returned to the tomb in the early 1980s.[3]

Excavation and contents

[edit]

In 1972 the tomb was fully excavated and cleared by the University of Minnesota Egyptian Expedition (UMEE). Excavation began immediately outside the tomb in an attempt to locate foundation deposits in the hope that they would shed light on the theory proposed by Reginald Engelbach that the tomb was begun for Tutankhamun; despite an extensive search, none were discovered. It was found that the drystone wall on the northern side of the entrance, thought to be a later addition, proved to be contemporary with the tomb's construction as it served the very real purpose of retaining quarried limestone chippings. Schaden stated that its removal prompted "a mass of limestone dust and chips [to] literally flow down the stairs towards the door of the tomb."[3]

Finds in the first corridor proved to be a mix of ancient and modern; the ancient finds consisted of a cornice from a small shrine or box, a small wooden beard, pieces of gold foil, and a fragmentary hieratic ostracon. The second set of stairs proved to be relatively free of debris but were in such poor condition that they were partially rebuilt with cement for safety. Darkened layers of fill at the far end of the second corridor indicated periods of flooding, although some thin smudges may suggest the presence of decayed wood. The second corridor contained a wooden hand from a statuette, and five discs of gilded copper embossed with rosette and star patterns crumpled into a ball. The doorway between the second corridor and the well-chamber was sealed in antiquity, as parts of the blocking were found there. The well chamber contained fill 119 centimetres (47 in) deep by the doorway, and yielded another gilded copper rosette, half of a human pelvis, another ushabti beard, a wooden leg from a statuette, and some pottery of Roman or Coptic date.[3]

No trace of blocking remained between the well chamber and the burial chamber. Inside the burial chamber the fill was uneven, with a gradual slope away from the door, and a depression in the centre from the removal of the sarcophagus; debris was piled against the walls. Hoping that the area close to the walls remained undisturbed, the centre of the chamber was cleared before excavating along the walls.

Many fragments of the sarcophagus box were encountered, but none of the lid; the lid was instead found intact, lying upside down against the east wall. Made of red granite, it has a vaulted shape with flat sides; the decoration is incised and infilled with green pigment. The top of the lid features two pairs of wedjat-eyes flanking a central column of text. The lid was found in the expected orientation, with the head end aligned to the north. However, the fragments of the sarcophagus found on the floor indicate that the box was oriented in the opposite direction, with the head to the south. The cartouches on the lid are entirely intact and the lid has no significant damage, suggesting that it was not toppled from atop the box. Schaden suggests that the lid may never have been put in place, and was instead left resting against the wall.

One section of alabaster teeth for a couch or bed, presumably Taweret-shaped, were found, indicating that Ay was interred with at least one funerary couch. Other finds included a piece of a coffin, part of a coffin-shaped lid, and the hand of a statuette, all of wood; more parts of a human skeleton were also encountered, along with an inscribed meat jar fragment.

The final chamber contained more fragments of the sarcophagus, further human bones, and the missing part of the meat jar inscription. The meat jar records that it contained "pressed meat for The Bull which was made [or prepared] as cargo for the nšmt-boat" and once formed part of the provisions for Ay's burial.[3]

Architecture

[edit]

The tomb consists of an entrance stair, two sloping corridors separated by a set of stairs, and three chambers.[5] The plan of the tomb is more similar to the tomb of Akhenaten at Amarna than it is to any earlier royal tomb;[3] it has a straight axis, a well chamber with no well, and a pillared hall which was used as the burial chamber. The burial chamber is also offset to one side of the axis. Beyond the burial chamber is a small undecorated canopic chamber. The tomb is constructed on a large scale, as corridors are wider than those of the earlier WV22. Slots for beams used to lower the sarcophagus in the corridor make a reappearance for the first time since KV20.[4][4]

Decoration

[edit]

Only the burial chamber is decorated, as was standard for the time.[3] The decorative scheme is similar to that seen in KV62, the tomb of Tutankhamun; several scenes are identical. Both tombs were possibly decorated by the same artists. Figures of the four sons of Horus appear for the first time in a royal tomb, above the doorway to the small canopic chamber. The west wall is decorated with a scene depicting Ay hunting in the marshes accompanied by his wife Tey; this is a unique occurrence for a New Kingdom royal tomb.[4] All images of Ay were thoroughly defaced, along with the removal of the cartouches of both Ay and Tey. Only a figure of the king's ka escaped erasure, possibly due to the figure bearing a slightly different title.[3]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Dodson & Hilton 2004, pp. 151, 154.

- ^ Clayton 1994, pp. 136–137.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Schaden 1984.

- ^ a b c d Reeves & Wilkinson 1996, pp. 128–129.

- ^ a b c d Belzoni 1820, pp. 123–124.

- ^ Wilkinson 1835, p. 123.

- ^ Lepsius 1853, p. 262.

Works cited

[edit]- Belzoni, Giovanni Battista (1820). Narrative of the Operations and Recent Discoveries Within the Pyramids, Temples, Tombs, and Excavations, in Egypt and Nubia; and of a Journey to the Coast of the Red Sea, in Search of the Ancient Berenice, and of Another to the Oasis of Jupiter Ammon. London: J. Murray. pp. 123–124. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- Clayton, Peter A. (1994). Chronicle Of The Pharaohs The Reign By Reign Record Of The Rulers And Dynasties Of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05074-0.

- Dodson, Aidan; Hilton, Dylan (2004). The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt (2010 paperback ed.). London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28857-3. Retrieved 15 April 2024.

- Lepsius, Richard (1853). Letters from Egypt, Ethiopia, and the peninsula of Sinai. Translated by Horner, Joanna B.; Horner, Leonora. London: H.G. Bohn. p. 262. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- Reeves, Nicholas; Wilkinson, Richard H. (1996). The Complete Valley of the Kings: Tombs and Treasures of Egypt's Greatest Pharaohs (2010 paperback reprint ed.). London: Thames & Hudson Ltd. pp. 128–129. ISBN 978-0-500-28403-2.

- Schaden, Otto J. (1984). "Clearance of the Tomb of King Ay (WV-23)". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. 21: 39–64. doi:10.2307/40000956. ISSN 0065-9991. JSTOR 40000956. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- Wilkinson, John Gardner (1835). Topography of Thebes, and General View of Egypt. London: J. Murray. p. 123. Retrieved 18 July 2021.