Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

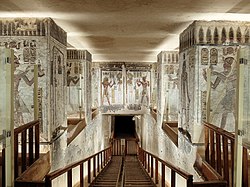

Tomb KV11 is the tomb of Pharaoh Ramesses III. It is located in the main valley of the Valley of the Kings. The tomb was originally started by Setnakhte, but abandoned when it unintentionally broke into the earlier tomb of Amenmesse (KV10). Setnakhte was buried in KV14. The tomb KV11 was later restarted and extended and on a different axis for Ramesses III.

Key Information

The tomb has been open since antiquity, and has been known variously as "Bruce's Tomb" (named after James Bruce who entered the tomb in 1768) and the "Harper's Tomb" (due to paintings of two blind harpers in the tomb).

Decoration

[edit]

The 188 m (617 ft) long tomb is beautifully decorated.

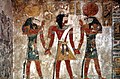

The second corridor is decorated with the Litany of Re. At the end of this corridor the axis of the tomb shifts. This third corridor is decorated with the Book of Gates and the Book of Amduat, and leads over a ritual shaft, and then into a four-pillared hall. This hall is again decorated with the Book of Gates. A fourth corridor decorated with scenes of the opening of the mouth ceremony leads into a vestibule, with scenes of the Book of the Dead, and then into the burial chamber.

The burial chamber is an eight-pillared hall in which stood the red quartzite sarcophagus (the box of which is now in the Louvre, while its lid is in the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge).[1] This chamber is decorated with Book of Gates, divine scenes and the Book of the Earth. Beyond this is a further set of annexes decorated with the Book of Gates. The outside of the sarcophagus features two scenes from the Amduat.[2]

Study and documentation of the tomb

[edit]The tomb was first mentioned by an English traveler Richard Pococke in the 1730s, but its first detailed description was given by James Bruce in 1768. Preliminary scientific studies were made by French scholars, who had come to Egypt with Napoleon, and then by, among others, J. F. Champollion, R. Lepsius, and in the 19th century, G. Lefebure.[3] In 1959, the Egyptian Department of Antiquities asked a Polish Egyptologist, Dr. Tadeusz Andrzejewski, to document the tomb. He started work under the auspices of the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology University of Warsaw but soon died. Twenty years later, the task of completing the documentation was given to Dr. Marek Marciniak.[4] The introduction of martial law in Poland hindered the publication of the results of his study. Since 2017, a German expedition from the Humboldt University and the Egyptian universities in Luxor and Qena work on the site. Apart from documenting the tomb, they also conduct conservation works.[1]

Gallery

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "The Ramesses III (KV 11) Publication and Conservation project". Retrieved 2020-08-27.

- ^ "Sarcophagus box of Ramesses III". Archived from the original on 3 Mar 2021.

- ^ Zsold Kiss (ed.), 50 lat polskich wykopalisk w Egipcie i na Bliskim Wschodzie, Warsaw: PCMA, 1986

- ^ "Dolina Królów, Grobowiec Ramzesa III". pcma.uw.edu.pl. Retrieved 2020-08-27.

- Reeves, N & Wilkinson, R.H. The Complete Valley of the Kings, 1996, Thames and Hudson, London.

- Siliotti, A. Guide to the Valley of the Kings and to the Theban Necropolises and Temples, 1996, A.A. Gaddis, Cairo.

External links

[edit]- Theban Mapping Project: KV11 includes description, images and plans of the tomb.

- Images taken from 3d models showing the breakthrough into KV10 from KV11